List of common misconceptions about arts and culture

Appearance

Each entry on this list of common misconceptions is worded as a correction; the misconceptions themselves are implied rather than stated. These entries are concise summaries; the main subject articles can be consulted for more detail.

Business

[edit]- Federal legal tender laws in the United States do not require that private businesses, persons, or organizations accept cash for payment, though it must be treated as valid payment for debts when tendered to a creditor.[1]

- Adidas is not an acronym for "All day I dream about sports", "All day I dream about soccer", or "All day I dream about sex". The company was named after its founder Adolf "Adi" Dassler in 1949. The earliest publication found of the latter backronym was in 1978, as a joke.[2][3]

- The letters "AR" in AR-15 stand for "ArmaLite Rifle", reflecting the company (ArmaLite) that originally manufactured the weapon. They do not stand for "assault rifle".[4][5]

- The Coca-Cola bottle's contour bottle was not designed by famous industrial designer Raymond Loewy.[6][7]

- The common image of Santa Claus (Father Christmas) as a jolly large man in red garments was not created by the Coca-Cola Company as an advertising tool. Santa Claus had already taken this form in American popular culture by the late 19th century, long before Coca-Cola used his image in the 1930s.[8]

- The Chevrolet Nova sold well in Latin American markets; General Motors did not rename the car. While no va does mean "doesn't go" in Spanish, nova was easily understood to mean "new".[9]

- Netflix was not founded after its co-founder Reed Hastings was charged a $40 late fee by Blockbuster. Hastings made the story up to summarize Netflix's value proposition; Netflix's founders were actually inspired by Amazon.[10]

- PepsiCo in no real sense ever owned the "6th most powerful navy" in the world after a deal with the Soviet Union. In 1989, Pepsi acquired several decommissioned warships as part of a barter deal.[11][12] The oil tankers were leased out or sold and the other ships sold for scrap.[13] A follow-on deal involved another 10 ships.[14]

Food and cooking

[edit]

- Searing does not seal in moisture in meat; it causes it to lose some moisture. Meat is seared to brown it and to affect its color, flavor, and texture.[15]

- Braising meat does not add moisture; it causes it to lose some moisture. Moisture appears to be added when the gentle cooking breaks down connective tissue and collagen, which lubricates and tenderizes fibers.[16][17]

- Mussels and clams that do not open when cooked can still be fully cooked and safe to eat.[18][19][20][better source needed]

- Twinkies, an American snack cake generally considered to be "junk food", have a shelf life of around 25 days, despite the common claim (usually facetious) that they remain edible for decades.[21] The official shelf life is 45 days. Twinkies normally remain on a store shelf for 7 to 10 days.[22]

- Packaged foods, when properly stored, can safely be eaten past their "expiration" dates in the US. While some US states regulate expiration dates for some products, generally "use-by" and "best-by" dates are manufacturer suggestions for best quality.[23]

- Storing bread in the refrigerator makes it go stale faster than leaving it at room temperature.[24][25] It does, however, slow mold growth.[26]

- Crystallized honey is not spoiled. The crystals are formed by low temperature crystallization, a high glucose level, and the presence of pollen. The crystallization can be reversed by gentle heating.[27][28]

- Seeds are not the spiciest part of chili peppers. In fact, seeds contain a low amount of capsaicin, one of several compounds which induce the hot sensation (pungency) in mammals. The highest concentration of capsaicin is located in the placental tissue (the pith) to which the seeds are attached.[29][30]

- Turkey meat is not particularly high in tryptophan, and does not cause more drowsiness than other foods. Drowsiness after large meals such as Christmas or Thanksgiving dinner generally comes from overeating.[31]

- Darker roasts of coffee do not always contain more caffeine than lighter roasts. When coffee is roasted, it expands and loses water. When the resultant coffee is ground and measured volumetrically, the denser lighter roasts have more coffee per cup, meaning they contain more caffeine.[32][33]

- Bourbon whiskey does not have to be distilled in Kentucky.[34] Bourbon is also distilled in states such as New York, California, Wyoming and Washington, as the legal requirement is only that it be made in the US. However, Kentucky does produce the majority of bourbon.[35][36]

- Using mild soap on well-seasoned cast-iron cookware will not damage the seasoning.[37] This is not because modern soaps are gentler than older soaps.[38]

- Sushi does not mean raw seafood; some sushi, such as kappamaki, contains no seafood. The word refers to the vinegar-prepared rice the dish contains.[39]

- Allspice is not a mix of spices.[40][41] It is a single spice, so called because it seems to combine the flavours and scents of many spices, especially cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves and black pepper.[42]

- Monosodium glutamate does not cause headaches and other feelings of discomfort, known as "Chinese restaurant syndrome".[43][44][45] Although there are reports of MSG sensitivity among a subset of the population, this has not been demonstrated in placebo‐controlled trials.[46]

Food and drink history

[edit]- Steak tartare was not invented by Mongol warriors who tenderized horse meat under their saddles.[47] It is likely named after the French tartar sauce, evolving from an early 20th century French dish where the sauce was served with steaks.[48]

- Marco Polo did not introduce pasta to Italy from China.[49] The misconception originated as promotional material in the Macaroni Journal, a newsletter published by an association of American pasta makers.[50]

- Spices were not used in the Middle Ages to mask the flavor of rotten meat before refrigeration. Spices were an expensive luxury item; those who could afford them could afford good meat, and there are no contemporaneous documents calling for spices to disguise the taste of bad meat.[51]

- Catherine de' Medici's cooks did not introduce Italian foods and techniques to the French royal court, laying the foundations for the development of French haute cuisine.[52]

- Whipped cream was not invented by François Vatel in 1661 and later named at the Château de Chantilly where it was notably served; similar recipes are attested at least a century earlier in France and England.[53][54]

- Dom Pérignon did not invent champagne. Wine naturally starts to bubble after being pressed, and bubbles at the time were considered a flaw which Pérignon worked unsuccessfully to eliminate.[55][56]

- Potato chips were not invented by a frustrated George Speck in response to a customer, sometimes given as Cornelius Vanderbilt, complaining that his French fries were too thick and not salty enough.[57][58] Recipes for potato chips were published as early as 1817.[59] The misconception was popularized by a 1973 advertising campaign by the St. Regis Paper Company.[60]

- George Washington Carver was not the inventor of peanut butter.[61] The first peanut butter related patent was filed by John Harvey Kellogg in 1895, and peanut butter was used by the Incas centuries prior to that.[62][63] Carver did compile hundreds of uses for peanuts, in addition to uses for pecans, and sweet potatoes.[62][64] An opinion piece by William F. Buckley Jr. may have been the source of the misconception.[61]

- Fortune cookies are not found in Chinese cuisine, despite their presence in Chinese restaurants in the United States and other Western countries. They originated in Japan and were introduced to the US by the Japanese.[65] In China, they are considered American, and are rare.[66]

- Julius Caesar did not invent Caesar salad. Its creator was Caesar Cardini, an Italian-American restauranteur, in Tijuana, Mexico, in 1924.[67][68]

- Hydrox is not a knock-off of Oreos. Hydrox, invented in 1908, predates Oreos by four years and was initially more popular than Oreos. The name "Hydrox" being said to sound like a laundry detergent contributed to its market decline.[69][70]

- The difference between the taste of "banana-flavored" candy and a real banana is not due to the former being specifically designed to replicate the taste of Gros Michel bananas, the cultivar that dominated the American banana market before the rise of Cavendish bananas. All banana cultivars derive their flavor from a complex mix of many compounds, while a single compound, isoamyl acetate, gives banana candy its flavor. Isoamyl acetate naturally occurs in bananas as well as many other fruits and fermented beverages.[71] It is more concentrated in Gros Michel bananas than in Cavendish bananas, but its use in candy production was due to its simple production, not any specific resemblance to a banana's flavor.[72][73]

Microwave ovens

[edit]

- Microwave ovens are not tuned to any specific resonant frequency for water molecules in the food.[74][75] They cook food via dielectric heating of polar molecules, notably water and fats.[76]

- Microwave ovens do not cook food from the inside out. 2.45 GHz microwaves can only penetrate approximately 1–1.5 inches (2+1⁄2–3+3⁄4 centimeters) into most foods. The inside portions of thicker foods are mainly heated by heat conducted from the outer layers.[77][78][79]

- The radiation produced by a microwave oven is non-ionizing, similar to visible light or radio waves. It therefore does not have the cancer risks associated with ionizing radiation such as X-rays and high-energy particles, nor does it render the food radioactive. All microwave radiation dissipates as heat. Long-term rodent studies to assess cancer risk have so far failed to identify any carcinogenicity from 2.45 GHz microwave radiation even with chronic exposure levels (i.e. large fraction of life span) far larger than humans are likely to encounter from any leaking ovens. The risk of injury from direct exposure to microwaves is not cumulative, but instead the result of a high-intensity exposure resulting in tissue burns, in much the same way that a high-intensity laser can burn.[80][81]

- Microwaving food does not significantly reduce its nutritive value more than other ways of heating and may preserve it better than other cooking processes due to shorter cooking times.[82]

Film and television

[edit]

- Ronald Reagan was never seriously considered for the role of Rick Blaine in the 1942 film Casablanca, eventually played by Humphrey Bogart. An early studio press release mentioned Reagan, but the studio already knew that Reagan was unavailable because of his upcoming military service.[83] Indeed, the producer had always wanted Bogart for the part.[84]

- Walt Disney Studios' Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was not the first animated film to be feature-length. El Apóstol, a lost 1917 Argentine silent film that used cutout animation, is considered the first.[85][86][87] The misconception comes from Snow White and the Seven Dwarves being the first feature-length film to be animated on cels.[88]

- The 1939 film The Wizard of Oz was not the first film in color. Kinemacolor was used starting in 1902, and the first Technicolor process debuted in 1917.[89][90]

Language

[edit]- The pronunciation of coronal fricatives in Spanish did not arise through imitation of a lisping king. Only one Spanish king, Peter of Castile, is documented as having a lisp, and the current pronunciation originated two centuries after his death.[91][92]

- Sign languages are not the same worldwide. Aside from the pidgin International Sign, each country generally has its own native sign language, and some have more than one.[93]

- The Chinese word for "crisis" (危机) is not composed of the symbols for "danger" and "opportunity"; the first does represent danger, but the second instead means "inflection point" (the original meaning of the word "crisis").[94][95] The misconception was popularized mainly by campaign speeches by John F. Kennedy.[94]

- The word "gringo" did not originate during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) as a corruption of "Green, go home!", in reference to the green uniforms of American troops.[96][97] The word originally simply meant "foreigner", and is probably a corruption of the Spanish word griego for "Greek" (along the lines of the idiom "It's Greek to me").[98][99]

English language

[edit]- Irregardless is a word. It appears in numerous dictionaries along with other nonstandard, slang, or colloquial terms.[100][101]

- It is permissible to end a sentence with a preposition.[102] The supposed rule against it originated in an attempt to imitate Latin, but modern linguists agree that it is a natural and organic part of the English language.[103] Similarly, modern style and usage manuals allow split infinitives.[104]

- African American Vernacular English speakers do not simply replace "is" with "be" across all tenses, with no added meaning. In fact, AAVE speakers use "be" to mark a habitual grammatical aspect not explicitly distinguished in Standard English.[105]

- "420" did not originate from the Los Angeles police or penal code for marijuana use.[106] California Penal Code section 420 prohibits the obstruction of access to public land.[106][107] The use of "420" started in 1971 at San Rafael High School, where a group of students would go to smoke at 4:20 pm.[106]

- Xmas did not originate as a secular plan to "take Christ out of Christmas".[108] X represents the Greek letter chi, the first letter of Χριστός (Christós), "Christ" in Greek,[109] as found in the chi-rho symbol (ΧΡ) since the 4th century. In English, "X" was first used as a scribal abbreviation for "Christ" in 1021.[110][111]

- The word crap did not originate as a back-formation of British plumber Thomas Crapper's apt surname.[112] The word crap ultimately comes from Medieval Latin crappa.[112][113]

- The word fuck did not originate in the Middle Ages as an acronym.[114] Proposed acronyms include "fornicating under consent of king" or "for unlawful carnal knowledge", used as a sign posted above adulterers in the stocks. Nor did it originate as a corruption of "pluck yew" (an idiom falsely attributed to the English for drawing a longbow).[114][115][116] It is most likely derived from Middle Dutch or other Germanic languages, where it either meant "to thrust" or "to copulate with" (fokken in Middle Dutch), "to copulate", or "to strike, push, copulate" or "penis".[115] Either way, these variations would have been derived from the Indo-European root word -peuk, meaning "to prick".[115]

- The expression "rule of thumb" did not originate from an English law allowing a man to beat his wife with a stick no thicker than his thumb, and there is no evidence that such a law ever existed.[117] The expression originates from the late seventeenth century from various trades where quantities were measured by comparison to the width or length of a thumb.[117][118]

- The term "blue laws", denoting laws banning certain activities on specific days, did not originate from such laws being originally written on blue paper.[119][120]

- The word the was never pronounced or spelled "ye" in Old or Middle English.[121] The confusion, seen in the common stock phrase "ye olde", derives from the use of the character thorn (þ), which in Middle English represented the sound now represented in Modern English by "th".[122] This evolved as early printing presses substituted the word the with "yͤ", a "y" character with a superscript "e".[123]

- Chocolate does not derive from the Nahuatl word chocolatl; early texts documenting the Nahuatl word for chocolate drink use a different term, cacahuatl, meaning "cacao water".[124]

- The anti-Italian slur wop did not originate from an acronym for "without papers"[125] or "without passport";[126][108] it is actually derived from the term guappo (roughly meaning thug), from the Spanish guapo.[127]

Law, crime, and military

[edit]

- Crime rates are declining for most types of crime, beginning in the mid to late 1980s and early 1990s.[128] In Europe, crime statistics show this is part of a broader pattern of crime decline since the late Middle Ages, with a reversal from the 1960s to the 1980s and 1990s, before the decline continued.[129] In the United States, between 1993 and 2022, the rate of violent crime per 100,000 people fell by almost 50%, and the rate of property crime fell by more than half.[130] The number of gun homicides also decreased.[131]

- Despite parents of many cultures having been regarded as having the right, if not duty, to physically punish misbehaving children to teach appropriate behavior such as by spanking, many studies consistently find that corporal punishment may have the opposite effect in the long run, decreasing long-term obedience,[132] while increasing the chances of aggressive behavior, depression, anxiety, suicide, and physical abuse.[133][134][135] (Some alternatives.)

- Chewing gum is not punishable by caning in Singapore. Although importing and selling chewing gum has been illegal in Singapore since 1992, and corporal punishment is still an applicable penalty for certain offenses in the country, the two facts are unrelated; chewing gum-related offenses have always been only subject to fines and incarceration, and the possession or consumption of chewing gum itself is not illegal.[136]

- Employees of the international police organization Interpol cannot conduct investigations, arrest criminals or use fake passports.[clarification needed] Interpol's role is facilitating international communication between law enforcement agencies of sovereign states.[137][138]

- No cases have been proven of strangers killing or permanently injuring children by intentionally hiding poisons or sharp objects such as razor blades in candy or apples during Halloween trick-or-treating and the belief has been "thoroughly debunked". However, in at least one case, adult family members have spread this story to cover up filicide.[139]

- There has never been a documented case of pet black cats being tortured or ritually sacrificed around Halloween. Where violent deaths of black cats have been documented around Halloween, the death has usually been ascribed to natural predators, such as coyotes, eagles, or raptors.[140]

- It is not necessary to wait 24 hours before filing a missing person report. When there is evidence of violence or of an unusual absence, it is important to start an investigation promptly.[141][142] Criminology experts say the first 72 hours in a missing person investigation are the most critical.[143]

- Perry Mason moments, in which a person on trial for a crime is suddenly exonerated by newly introduced revelations, are exceptionally rare in real-life court proceedings, despite their ubiquity in legal drama. The vast majority of evidence is unveiled in pretrial discovery; should new revelations occur, a trial is usually stayed until both the prosecution and defense can review it.[144]

United States

[edit]

- Undocumented immigrants in the US have substantially lower crime rates than US-born citizens.[145][146] Compared to undocumented immigrants, US-born citizens are more than twice as likely to be arrested for violent crimes, 2.5 times more likely to be arrested for drug crimes, and over 4 times more likely to be arrested for property crimes.[146] Immigrants are 60% less likely to be incarcerated than US-born citizens.[147]

- The First Amendment to the United States Constitution generally prevents only government restrictions on the freedoms of religion, speech, press, assembly, or petition,[148] not restrictions imposed by other entities unless they are acting on behalf of the government.[149][150] Other laws may limit the ability of private businesses and individuals to restrict the speech of others.[151]

- In the United States, a defendant may not have their case dismissed simply because they were not read their Miranda rights at the time of their arrest. Miranda warnings cover the rights of a person when they are taken into custody and then interrogated by law enforcement.[152] If a person is not given a Miranda warning before the interrogation is conducted, statements made by them during the interrogation may not be admissible in a trial. The prosecution may still present other forms of evidence, or statements made during interrogations where the defendant was read their Miranda rights, to get a conviction.[153]

- The United States does not require police officers to identify themselves as police in the case of a sting or other undercover work, and police officers may lie when engaged in such work.[154] Claiming entrapment as a defense instead focuses on whether the defendant was improperly induced by undue pressure from government officials to commit crimes they would not have otherwise committed.[155]

- It is not illegal in the US to shout "fire" in a crowded theater. Although this is often given as an example of speech that is not protected by the First Amendment, it is not now nor has it ever been binding law. The phrase originates from Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.'s opinion in the United States Supreme Court case Schenck v. United States in 1919, which held that the defendant's speech in opposition to the draft during World War I was not protected free speech. However, that case was not about shouting "fire" and the decision was later overturned by Brandenburg v. Ohio in 1969.[156][157]

- The US Armed Forces have generally forbidden military enlistment as a form of deferred adjudication (that is, an option for convicts to avoid jail time) since the 1980s.[158] US Navy protocols discourage the practice, while the other four branches have specific regulations against it.[159]

- Last meal requests do not have to be fulfilled.[160] States have various restrictions on what can be requested, up to not permitting them at all.[161]

- Although popularly known as the "red telephone", the Moscow–Washington hotline was never a telephone line, nor were red phones used. The first implementation of the hotline used teletype equipment, which was replaced by facsimile (fax) machines in 1988. Since 2008, the hotline has been a secure computer link over which the two countries exchange email.[162] Moreover, the hotline links the Kremlin to the Pentagon, not the White House.[163][164]

- Likewise, the nuclear football, the briefcase used by presidents to launch nuclear attacks, does not contain a large red button to launch an attack. Rather, its primary use is to confirm the president's identity, and to facilitate communication with the Pentagon.[165][166][167]

- Twinkies were not claimed to be the cause of San Francisco mayor George Moscone's and supervisor Harvey Milk's murders. In the trial of Dan White, the defense successfully argued White's diminished capacity as a result of depression. While eating Twinkies was cited as evidence of this depression, it was never claimed to be the cause of the murders.[168][169]

- Neither the Mafia nor other criminal organizations regularly use or have used cement shoes to drown their victims.[170] There are only two documented cases of this method being used in murders: one in 1964 and one in 2016 (although, in the former, the victim had concrete blocks tied to his legs rather than being enclosed in cement).[171] The French Army did use cement shoes on Algerians killed in death flights during the Algerian War.[172]

- Embalming is not legally required in the United States.[173][174] The Federal Trade Commission passed a rule in 1984 forbidding making this claim, to prevent the funeral industry from promoting the misconception for financial gain.[175]

Literature

[edit]- Many quotations are incorrect or attributed to people who never uttered them, and quotations from obscure or unknown authors are often attributed to more famous figures. Commonly misquoted individuals include Mark Twain, Albert Einstein, Adolf Hitler, Winston Churchill, Abraham Lincoln, William Shakespeare, Confucius, Sun Tzu, and the Buddha.[176]

- Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein is named after the fictional scientist Victor Frankenstein, who created the sapient creature in the novel, not the creature itself, which is never named in the novel and is now usually called Frankenstein's monster.[177] However, as later adaptations started to refer to the monster itself as Frankenstein, this usage became well-established, and some no longer regard it as erroneous.[178][179]

- Ernest Hemingway did not author the flash fiction story "For sale: baby shoes, never worn".[180] The story was not attributed to him until decades after he died.[181]

Fine arts

[edit]

- Ancient Greek and Roman sculptures were originally painted in colors; they appear white today only because the original pigments have deteriorated. Some well-preserved statues still bear traces of their original coloration.[182][183]

- Michelangelo stood up rather than lay down on scaffolding while painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.[184][185]

- The 1930 painting American Gothic depicts a father and adult daughter, not a husband and wife.[186][187]

Music

[edit]Classical music

[edit]- The musical interval tritone was not banned by the Catholic Church and was not associated with devils during the Middle Ages.[188][189] Early medieval music used the tritone in Gregorian chant for certain modes.[190] Guido of Arezzo (c. 991 – c. 1033) was the first theorist to discourage the interval.[190]

- Mozart did not die from poisoning, and was not poisoned by his colleague Antonio Salieri or anyone else.[191] The rumor originated soon after Salieri's death and was dramatized in Alexander Pushkin's play Mozart and Salieri (1832), and later in the 1979 play Amadeus by Peter Shaffer and the subsequent 1984 film Amadeus.[192]

- The minuet in G major by Christian Petzold is commonly attributed to Johann Sebastian Bach, although the piece was identified in the 1970s as a movement from a harpsichord suite by Petzold. The misconception stems from Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach, a book of sheet music by various composers (mostly Bach) in which the minuet is found.[193] Compositions that are doubtful as works of Bach are cataloged as "BWV Anh.", short for "Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis Anhang" ("Bach works catalogue annex"); the minuet is assigned to BWV Anh. 114.

- Listening to Mozart or classical music does not enhance intelligence (or IQ). A study from 1993 reported a short-term improvement in spatial reasoning.[194][195] However, the weight of subsequent evidence supports either a null effect or short-term effects related to increases in mood and arousal, with mixed results published after the initial report in Nature.[196][197][198][199]

- The "Minute Waltz" takes, on average, two minutes to play as originally written.[200] Its name comes from the adjective minute, meaning "small", and not the noun spelled the same.[201]

Popular music

[edit]- "Edelweiss" is not the national anthem of Austria, but an original composition created for the 1959 musical The Sound of Music.[202] The Austrian national anthem is "Land der Berge, Land am Strome" ("Land of the Mountains, Land on the River [Danube]").[203]

- The Beatles' 1965 appearance at Shea Stadium was not the first time that a rock concert was played at a large, outdoor sports stadium in the United States; such venues were employed by Elvis Presley in the 1950s and the Beatles themselves in 1964.[204]

- The Monkees did not outsell the Beatles' and the Rolling Stones' combined record sales in 1967. Michael Nesmith originated the claim in a 1977 interview as a prank.[205]

- The Rolling Stones were not performing "Sympathy for the Devil" at the 1969 Altamont Free Concert when Meredith Hunter was stabbed to death by a member of the local Hells Angels chapter that was serving as security. The stabbing occurred later as the band was performing "Under My Thumb".[206][207]

- Concept albums did not begin with rock music in the 1960s. The format had already been employed by singers such as Frank Sinatra in the 1940s and 1950s.[208]

- Cass Elliot (of The Mamas & the Papas) did not die from choking on a ham sandwich.[209][210] This falsehood was initiated by her manager who wanted to avoid the implication that her death was associated with substance abuse.[211]

- Phil Collins did not write his 1981 hit "In the Air Tonight" about witnessing someone drowning and then confronting the person in the audience who let it happen. According to Collins himself, it was about his emotions when divorcing from his first wife.[212]

- Popular musicians are not more likely to die at the age of 27. The notion of a "27 Club" arose after the deaths, in a ten-month period, of Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Jim Morrison, and later the deaths of Kurt Cobain and Amy Winehouse. Statistical studies have shown that there is no scientific basis for this idea.[213][214][215]

Religion

[edit]Buddhism

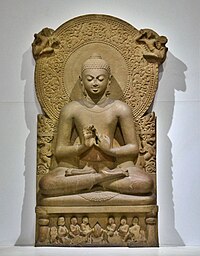

[edit]- The chubby, bald monk with lengthened ears who is often depicted laughing, known as the "fat Buddha" or "laughing Buddha" in the West, is not the actual Buddha, but a 10th-century Chinese Buddhist folk hero by the name of Budai.[216] The historical Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, who lived in the 5th century BC, is most often depicted in normal weight and concentrated in meditation.

Christianity

[edit]- Jesus was most likely not born on December 25, when his birth is traditionally celebrated as Christmas. It is more likely that his birth was in either the season of spring or perhaps summer. Although the Common Era ostensibly counts the years since the birth of Jesus,[217] it is unlikely that he was born in either AD 1 or 1 BC, as such a numbering system would imply. Modern historians estimate a date closer to between 6 BC and 4 BC.[218]

- The Bible does not say that exactly three magi came to visit the baby Jesus, nor that they were kings, or rode on camels, or that their names were Caspar, Melchior, and Balthazar, nor what color their skin was.[219][220][221][citation needed] Three magi are inferred because three gifts are described, but the Bible says only that there was more than one magus.[222][223][224]

- The idea that Mary Magdalene was a prostitute before she met Jesus is not found in the Bible or in any of the other earliest Christian writings. It has been a disputed doctrine in several theological traditions whether Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany (who anoints Jesus' feet in John 11:1–12),[227] and the unnamed "sinful woman" who anoints Jesus' feet in Luke 7:36–50[228] were the same woman.[225][226]

- Paul the Apostle's name was not changed from Saul. He was born a Jew, with Roman citizenship inherited from his father, and thus carried both a Hebrew and a Greco-Roman name from birth, as mentioned by Luke in Acts 13:9:[229] "...Saul, who also is called Paul...".[230][231]

- The Roman Catholic dogma of the Immaculate Conception is unrelated to the Christian doctrine that Mary conceived and gave birth to Jesus while remaining a virgin. The Immaculate Conception is the belief that Mary was free of original sin from the moment of her own conception by her parents, Joachim and Anne. A less common mistake is to think that the Immaculate Conception means that Mary herself was conceived without sexual intercourse.[232][233]

- Roman Catholic dogma does not say that the pope is either sinless (as is commonly believed among non-Catholic Christians)[234] or always infallible.[235] Catholic dogma since 1870 does state that a divine revelation by the pope (generally called ex cathedra) is free from error, but it does not hold that he is always free from error, even when speaking in his official capacity.[236]

- Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) no longer practice polygamy.[237][238][239][240] The Church excommunicates any members who practice polygamy within the organization.[241] Some Mormon fundamentalist sects do practice polygamy.[242][243]

- The First Council of Nicaea did not establish the books of the Bible. The Old Testament had likely already been established by Hebrew scribes before Christ. The development of the New Testament canon was mostly completed in the third century before the Nicaea Council was convened in 325;[244] it was finalized, along with the deuterocanon, at the Council of Rome in 382.[245]

- Constantine the Great did not make Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire. While he was the first Christian emperor and promoted religious tolerance with the Edict of Milan, Christianity was not declared the official religion of the Roman Empire until 380 AD, some 43 years after Constantine's death.[246][247]

- The Seven Deadly Sins are never listed in the Bible. The concept originated with Tertullian, and originally consisted of nine vices.[248] This was later reduced to seven by Gregory I.[249]

Islam

[edit]- The burqa (also transliterated as burka or burkha) is often confused with other types of head-wear worn by Muslim women, particularly the niqāb and the hijab. A burqa covers the body, head, and face, with a mesh grille to see through. A niqab covers the hair and face, excluding the eyes. A hijab covers the hair and chest but not the face.[250]

- Not all Muslim women wear face or head coverings.[251]

- A fatwa is a generally non-binding legal opinion issued by an Islamic scholar under Islamic law; it is therefore commonplace for fatawa from different authors to disagree. The misconception that it is a death sentence stems from a decree issued by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini of Iran in 1989 where he said that the author Salman Rushdie had earned a death sentence for blasphemy. It is debated whether this was a fatwa.[252][253][254]

- The word jihad does not always mean 'holy war'; its literal meaning in Arabic is 'struggle'. While there is such a thing as jihad by the sword, jihad can be any spiritual or moral effort or struggle,[255][256][257] such as seeking knowledge, putting others before oneself, and inviting others to Islam.[258]

- The Quran does not promise martyrs 72 virgins in heaven. It does mention that virgin female companions, houri, are given to all people, martyr or not, in heaven, but no number is specified.[259] The source for the 72 virgins is a hadith in Sunan al-Tirmidhi by Imam Tirmidhi.[260][261] Hadiths are sayings and acts of Muhammad as reported by others, not part of the Quran itself.[262][260]

Judaism

[edit]

- The forbidden fruit mentioned in the Book of Genesis is never identified as an apple,[263] as widely depicted in Western art. The original Hebrew texts mention only fruit.[264][265]

- While tattoos are forbidden by the Book of Leviticus, Jews with tattoos are not barred from being buried in a Jewish cemetery, just as violators of other prohibitions are not barred, as is commonly believed among American Jews.[266]

Sports

[edit]- Artificial turf is not maintenance free. It requires regular maintenance, such as raking and patching, to keep it functional and safe.[267]

- The name golf is not an acronym for "Gentlemen Only, Ladies Forbidden".[268][269] It may have come from the Dutch word kolf or kolve, meaning "club",[269] or from the Scottish word goulf or gowf meaning "to strike or cuff".[268]

- Baseball was not invented by Abner Doubleday, nor did it originate in Cooperstown, New York. It is believed to have evolved from the bat-and-ball game rounders and first took its modern form in New York City.[270]

- The black belt in martial arts does not necessarily indicate expert level.[271] It was introduced for judo in the 1880s to indicate competency at all of the basic techniques of the sport. Promotion beyond 1st dan (the first black belt rank) varies among different martial arts.[272]

- The use of triangular corner flags in English football is not a privilege reserved for those teams that have won an FA Cup in the past, as depicted in a scene in the film Twin Town. The Football Association's rules are silent on the subject, and the decision over what shape flag to use has been up to the individual club's groundskeepers.[273]

- India did not withdraw from the 1950 FIFA World Cup because their squad wanted to play barefoot. In reality, India withdrew because the country's managing body, the All India Football Federation (AIFF), was insufficiently prepared for the team's participation.[274]

Video games

[edit]- There is no definitive proof that violent video games cause people to become violent. Some studies have found no link between aggression and violent video games,[275][276] and the popularity of gaming has coincided with a decrease in youth violence.[277][278] The moral panic surrounding video games in the 1980s through to the 2020s, alongside several studies and incidents of violence and legislation in many countries, likely contributed to proliferating this idea.[279][280]

- The so-called "Nuclear Gandhi" glitch, in which peaceful leader Mahatma Gandhi would become unusually aggressive if democracy was adopted,[281] did not exist in either the original Civilization game or Civilization II. The games' designer Sid Meier attributed the origins of the rumor to both a TV Tropes thread and a Know Your Meme entry,[282] while Reddit and a Kotaku article helped popularize it.[283] Gandhi's supposed behavior did appear in the 2010 Civilization V[282] as a joke, and in 2016's VI[284] as a reference to the legend.

- The Japanese government did not pass a law banning Square Enix from releasing the Dragon Quest games on weekdays due to it causing too many schoolchildren to cut class. This rule is self-imposed by the developers themselves.[285]

- The release of Space Invaders in 1978 did not cause a shortage of ¥100 coins in Japan. An advertising campaign by Taito and an erroneous 1980 article in New Scientist are the sources of this claim.[286]

References

[edit]- ^ a. "Legal Tender Status". Resource Center. U.S. Department of the Treasury. January 4, 2011. Archived from the original on January 24, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

b. "Is it legal for a business in the United States to refuse cash as a form of payment?". Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve System. June 17, 2011. Archived from the original on January 21, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

c. "What is A "Legal Tender Law"? And, is It a Problem?". Forbes. Archived from the original on June 3, 2018. - ^ VanHooker, Brian (October 27, 2020). "The True Story Behind Adidas' 'All Day I Dream About Sex' (And Other Bogus Brand Acronyms)". MEL Magazine. Archived from the original on April 3, 2023. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ "Pop Culture Dictionary: Adidas". Dictionary.com. April 23, 2018. Archived from the original on November 29, 2023. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ Myre, Greg (February 28, 2018). "A Brief History Of The AR-15". NPR. Archived from the original on May 13, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Palma, Bethania (September 9, 2019). "Does 'AR' in AR-15 Stand for 'Assault Rifle'?". Snopes. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Bayley, Stephen (February 7, 2015). "The art of Coke". The Spectator. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara (May 2, 1999). "Was the Coca-Cola Bottle Design an Accident?". Snopes. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ a. Mikkelson, David (December 18, 2008). "Did Coca-Cola Invent the Modern Image of Santa Claus?". Snopes. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

b. "Coca-Cola's Santa Claus: Not The Real Thing!". BevNET.com. December 18, 2006. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved January 19, 2007.

c. Boissoneault, Lorraine (December 19, 2018). "A Civil War Cartoonist Created the Modern Image of Santa Claus as Union Propaganda". Smithsonian. Retrieved June 21, 2024. - ^ Mikkelson, Barbara and David (March 19, 2011). "Don't Go Here". Snopes. Archived from the original on June 14, 2019. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ a. Rodriguez, Ashley (August 29, 2017). "Netflix was founded 20 years ago today because Reed Hastings was late returning a video". Quartz. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

b. Keating, Gina (September 24, 2013). "Prologue". Netflixed: The Epic Battle for America's Eyeballs. Portfolio. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-1-59184-659-8.

c. Carey, Alexis (January 18, 2020). "True story behind Netflix's rise – and the downfall of Blockbuster". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

d. Castillo, Michelle (May 23, 2017). "Reed Hastings' story about the founding of Netflix has changed several times". CNBC. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2022. - ^ Lewis, Flora (May 10, 1989). "Foreign Affairs; Soviets Buy American". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 5, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Musgrave, Paul (November 27, 2021). "The Doomed Voyage of Pepsi's Soviet Navy". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on January 18, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Clarke, Kaiyah (May 24, 2022). "Fact Check: NO Pepsi Navy – U.S.-Soviet Deal Did NOT Make Pepsi The '6th Most Powerful Military In The World'". Lead Stories. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ Ewbank, Anne (January 12, 2018). "When the Soviet Union Paid Pepsi in Warships". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ a. "Does searing meat really seal in moisture?". Cookthink.com. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

b. McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking (2nd ed.). Scribner. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1. - ^ "The Truth About Braising". America's Test Kitchen. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Lopez-Alt, J Kenji (2015). "Soups, Stews, and the Science of Stock". The Food Lab: Better Home Cooking Through Science. America: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-08108-4. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Marino, Melissa (June 2007). "Blue Mussels: An Open and Shut Case" (PDF). FISH. Fisheries Research and Development Corporation. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 18, 2024. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ Kruszelnicki, Karl (October 29, 2008). "Mussel myth an open and shut case". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ Tomky, Naomi (April 2018). "A Guide to Clam Types and What to Do With Them". Serious Eats. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ Sagon, Candy (April 13, 2005). "Twinkies, 75 Years and Counting". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ a. Kelley, Tina (March 23, 2000). "Twinkie Strike Afflicts Fans With Snack Famine". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2012. b. Greenfieldboyce, Nell (October 15, 2020). "A Disturbing Twinkie That Has, So Far, Defied Science". All Things Considered. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ a. "Food Product Dating". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2024. b. Abrahamian, Atossa Araxia (September 19, 2013). "Harvard study finds food expiration labels are misleading". Reuters. Archived from the original on December 13, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Tana, Sara (July 26, 2021). "8 Food Storage Mistakes That Are Costing You Money". Allrecipes.com. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Gritzer, Daniel (February 28, 2023). "Does Refrigeration Really Ruin Bread?". Serious Eats. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Olaechea, Carlos (June 14, 2023). "Refrigerating Bread Isn't Always Bad". EatingWell. Retrieved July 6, 2024.

- ^ Sertich Velie, Marissa (August 10, 2018). "The Serious Eats Guide to Sugar". Serious Eats. Archived from the original on May 27, 2024. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Pearson, Gwen (March 7, 2014). "What Do You Do With Crystallized Honey?". Wired. Archived from the original on June 14, 2023. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ "New Mexico State University – College of Agriculture and Home Economics (2005)". Archived from the original on May 4, 2007.

- ^ Tandon, G L; Dravid, S V; Siddappa, G S (January 1964). "Oleoresin of Capsicum (Red Chilies)—Some Technological and Chemical Aspects". Journal of Food Science. 29 (1): 2. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1964.tb01683.x. ISSN 0022-1147.

- ^ Vreeman, Rachel C; Carroll, Aaron E (20 December 2007). "Medical myths". The BMJ. 335 (7633): 1288–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.39420.420370.25. PMC 2151163. PMID 18156231.

- ^ "Caffeine Content of Coffee: Dark Roast vs. Light Roast". America's Test Kitchen. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Lipka, Mitch (March 27, 2014). "Your money: Getting the biggest caffeine buzz for your buck". Reuters. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Kiniry, Laura (June 13, 2013). "Where Bourbon Really Got Its Name and More Tips on America's Native Spirit". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Minnick, Fred (October 23, 2015). "Is Kentucky the Home of Bourbon?". Whisky Magazine. No. 131. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Carroll, James R (May 9, 2024). "Congress resolution marks bourbon's unique status". Courier Journal. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Sullivan, Michael (September 12, 2023). "How to Clean and Season Cast-Iron Cookware". Wirecutter. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ McManus, Lisa (February 15, 2022). "Is It OK to Use Soap on Cast Iron?". America's Test Kitchen. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara (October 5, 2002). "Sushi Definition". Snopes. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ Francis, Ali (December 1, 2021). "Allspice Is the Berry—Yes, Berry—That Can Do It All". Bon Appetit. Archived from the original on April 8, 2024. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Mincey, Rai (February 24, 2021). "What is Allspice?". Allrecipes.com. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ "Allspice: Etymology". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ "Questions and Answers on Monosodium glutamate (MSG)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 19 November 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ Obayashi, Y; Nagamura, Y (17 May 2016). "Does monosodium glutamate really cause headache?: a systematic review of human studies". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 17 (1): 54. doi:10.1186/s10194-016-0639-4. PMC 4870486. PMID 27189588.

- ^ Wei, Will (16 June 2014). The Truth Behind Notorious Flavor Enhancer MSG. Business Insider (Podcast). Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ Freeman, Matthew (2006). "Reconsidering the effects of monosodium glutamate: A literature review". Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 18 (10): 482–86. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00160.x. PMID 16999713. S2CID 21084909.

- ^ Smith, Craig S (April 6, 2005). "The Raw Truth: Don't Blame the Mongols (or Their Horses)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 26, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Jack, Albert (2011-09-06). What Caesar Did for My Salad: The Curious Stories Behind Our Favorite Foods. Penguin. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-101-55114-1.

- ^ Dickie, John (2008). Delizia!: The Epic History of the Italians and Their Food. New York: Free Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-7432-7799-0.

- ^ Serventi, Silvano; Sabban, Françoise (2002). Pasta: The Story of a Universal Food [La Pasta: Storia e cultura di un cibo universale]. Translated by Shugaar, Antony. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-231-12442-2.

- ^ a. Freedman, Paul (2012). Claflin, Kyri; Scholliers, Peter (eds.). Writing Food History: A Global Perspective. London: Berg Publishers. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-84788-809-9.

b. Dalby, Andrew (2000). Dangerous Tastes: The Story of Spices. University of California Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-520-23674-5.

c. Jotischky, Andrew (2011). A Hermit's Cookbook: Monks, Food and Fasting in the Middle Ages. Bloomsbury. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-4411-5991-5.

d. Krondl, Michael (2007). The Taste of Conquest: The Rise and Fall of the Three Great Cities of Spice. Ballantine Books. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-345-48083-5. - ^ a. Ketcham Wheaton, Barbara (2011). Savoring the Past: The French Kitchen and Table from 1300 to 1789. Atria Publishing Group. pp. 43–51. ISBN 978-1-4391-4373-5. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

b. Mennell, Stephen (1996). All Manners of Food: Eating and Taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the Present (2nd ed.). University of Illinois Press. pp. 65–66, 69–71. ISBN 978-0-252-06490-6. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

c. Campanini, Antonella (December 18, 2018). The New Gastronome: The Illusive Story Of Catherine de' Medici: A Gastronomic Myth. Archived from the original on December 29, 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2020. Summarizing Campanini, Antonella; Bienassis, Loïc (2018). "La reine à la fourchette et autres histoires. Ce que la table française emprunta à l'Italie: analyse critique d'un mythe". In Quellier, Florent; Briost, Pascal (eds.). La Table de la Renaissance: Le mythe italien. Presses universitaires de Rennes. ISBN 978-2-7535-7406-9. - ^ "Histoire – La chantilly, un dessert de légende". RTBF (in French). July 15, 2021. Archived from the original on January 3, 2024. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ a. Tebben, Maryann Bates (2014). Sauces: A Global History. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-1-78023-413-7. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

b. "Histoire de la Crème Chantilly". Château de Chantilly. Archived from the original on April 16, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2024. - ^ Foreman, Amanda (December 9, 2021). "The Many Inventors of Champagne". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ Kladstrup, Don; Kladstrup, Petie (2005). "Chapter 1: The Monarch and the Monk". Champagne: How the World's Most Glamorous Wine Triumphed Over War and Hard Times. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 978-0-06-073792-4.

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara (November 10, 2000). "Potato Chip Origin". Snopes. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Fox, William S.; Banner, Mae G. (April 1983). "Social and Economic Contexts of Folklore Variants: The Case of Potato Chip Legends". Western Folklore. 42 (2): 114–126. doi:10.2307/1499968. JSTOR 1499968.

- ^ McElwain, Aoife (June 17, 2019). "Did Tayto really invent cheese and onion crisps?". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Burhans, Dirk E (2008). "Creation Myths". Crunch!: A History of the Great American Potato Chip. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-0-299-22770-8.

- ^ a b Krampner, Jon (2013). Creamy and Crunchy: An Informal History of Peanut Butter, the All-American Food. Columbia University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-231-16233-3.

- ^ a b "Who Invented Peanut Butter?". National Peanut Board. Archived from the original on November 25, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ Wheeling, Kate (January 2021). "A Brief History of Peanut Butter". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Cannon, William (February 6, 2017). "A True Renaissance Man". American Scientist. Archived from the original on April 3, 2023. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ Lee, Jennifer 8 (January 16, 2008). "Solving a Riddle Wrapped in a Mystery Inside a Cookie". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 18, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara (May 21, 2008). "Origin of Fortune Cookies". Snopes. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Birrell, Nicki (July 4, 2024). "Caesar Centenary: What's the story behind the famous salad?". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ O'Conner, Patricia T; Kellerman, Stewart (2009). Origins of the Specious: Myths and Misconceptions of the English Language. New York: Random House. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-4000-6660-5.

- ^ LeClair, Catherine (August 5, 2020). "How the Oreo cookie went from unknown knock-off to the world's most popular cookie, as a result of a sibling rivalry between baker brothers". Business Insider. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ Rhoades, Christopher (January 19, 2008). "The Hydrox Cookie Is Dead, and Fans Won't Get Over It". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 12, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Technical Resources International, Inc (November 1994). "Summary of Data For Chemical Selection: Isoamyl Acetate" (PDF). National Toxicology Program. United States Department of Health and Human Services. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 22, 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Baraniuk, Chris. "The secrets of fake flavours". BBC. Archived from the original on March 21, 2024. Retrieved 2022-07-30.

- ^ Mayer, Johanna (September 27, 2017). "Why Don't Banana Candies Taste Like Real Bananas?". Science Friday. Archived from the original on February 4, 2024. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Soltysiak, Michal; Celuch, Malgorzata; Erle, Ulrich (June 2011). "Measured and simulated frequency spectra of the household microwave oven". 2011 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium. pp. 1–4. doi:10.1109/MWSYM.2011.5972844. ISBN 978-1-61284-754-2.

- ^ Bloomfield, Louis. "Question 1456". How Everything Works. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2012.

- ^ Baird, Christopher S. (15 October 2014). "Why are the microwaves in a microwave oven tuned to water". Science Questions with Surprising Answers. Canyon, TX: West Texas A&M University. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ "Microwave Technology Penetration Depths". pueschner.com. Püschner GMBH + CO KG MicrowavePowerSystems. Archived from the original on March 4, 2023. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- ^ "Cooking with Microwave Ovens". Food Safety and Inspection Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ "Resources for You (Radiation-Emitting Products): Microwave Oven Radiation". Food and Drug Administration. FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. December 12, 2017. Archived from the original on November 24, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Frei, MR; Jauchem, JR; Dusch, SJ; Merritt, JH; Berger, RE; Stedham, MA (1998). "Chronic, low-level (1.0 W/kg) exposure of mice prone to mammary cancer to 2450 MHz microwaves". Radiation Research. 150 (5): 568–76. Bibcode:1998RadR..150..568F. doi:10.2307/3579874. JSTOR 3579874. PMID 9806599.

- ^ Frei, MR; Berger, RE; Dusch, SJ; Guel, V; Jauchem, JR; Merritt, JH; Stedham, MA (1998). "Chronic exposure of cancer-prone mice to low-level 2450 MHz radiofrequency radiation". Bioelectromagnetics. 19 (1): 20–31. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-186X(1998)19:1<20::AID-BEM2>3.0.CO;2-6. PMID 9453703.

- ^ Komaroff, Anthony L (June 12, 2015). "Ask the doctor: Microwave's impact on food". Harvard Health Publishing. Harvard University. Archived from the original on April 14, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (1992). Round Up the Usual Suspects: The Making of Casablanca – Bogart, Bergman, and World War II. Hyperion. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-56282-761-8.

- ^ a. Sklar, Robert (1992). City Boys: Cagney, Bogart, Garfield. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-691-04795-9.

b. Mikkelson, Barbara and David P. (August 17, 2007). "The Blaine Truth". Snopes. Retrieved March 25, 2012. - ^ Maher, John (October 8, 2020). "10 Tragically, Irretrievably Lost Pieces of Animation History". Vulture. Archived from the original on June 22, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Sisterson, Dennis (March 28, 2017). "Magic Wilderness: El Apóstol & Peludópolis". Skwigly. Archived from the original on December 3, 2021. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- ^ Bendazzi, Giannalberto (2017). "The First Feature Length Animated Film in History". Twice the First: Quirino Cristiani and the Animated Feature Film. CRC Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-351-37179-7. Archived from the original on April 3, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

On the other hand, the movie was not widely successful, and appealed to a small portion of the population. It was strictly for a Buenos Aires audience: nobody in the provinces even saw it because it was not distributed there. And likewise, given the subject, it was not possible to export the film to other nations, not even to a close cousin similar to Uruguay.

- ^ "Snow White colored animation celluloid". National Museum of American History. Retrieved September 23, 2023.

- ^ Higgins, Scott (2000). "Demonstrating Three-Colour Technicolor: "Early Three-Colour Aesthetics and Design"". Film History. 12 (4): 358–383. doi:10.2979/FIL.2000.12.3.358 (inactive November 1, 2024). ISSN 0892-2160. JSTOR 3815345.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "First Color Movie – Everything You Need to Know". Nashville Film Institute. February 28, 2022. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ Oldfield, Molly; Mitchinson, John (May 5, 2011). "QI: Quite interesting facts about Spain". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Erichsen, Gerald (January 11, 2019). "Did a Royal Edict Give Spaniards a Lisp?". ThoughtCo. Dotdash Meredith. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- ^ a. Lewis, M. Paul; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2013). "Deaf sign language". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (17th ed.). SIL International. Archived from the original on November 26, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

b. Supalla, Ted; Webb, Rebecca (2013). "The grammar of international sign: A new look at pidgin languages.". In Reilly, Judy Snitzer; Emmorey, Karen (eds.). Language, Gesture, and Space. Psychology Press. pp. 333–52. ISBN 978-1-134-77966-6. Archived from the original on January 21, 2023. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

c. Omar, Hasuria Che (2009). The Sustainability of the Translation Field. ITBM. p. 293. ISBN 978-983-42179-6-9. Archived from the original on January 21, 2023. Retrieved February 21, 2017. - ^ a b Zimmer, Benjamin (March 27, 2007). "Crisis = danger + opportunity: The plot thickens". Language Log. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 19, 2009.

- ^ a. Adams, Cecil (November 3, 2000). "Is the Chinese word for "crisis" a combination of "danger" and "opportunity"?". The Straight Dope. Archived from the original on January 22, 2016. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

b. Mair, Victor H. "danger + opportunity ≠ crisis: How a misunderstanding about Chinese characters has led many astray". pinyin.info. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2024. - ^ "Where does the word "Gringo" come from?". The Yucatan Times. April 27, 2018. Archived from the original on March 22, 2022. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ Sayers, William (May 20, 2009). "An Unnoticed Early Attestation of gringo 'Foreigner': Implications for Its Origin". Bulletin of Spanish Studies. 86 (3): 323–330. doi:10.1080/14753820902937946.

- ^ Ramirez, Aida (August 7, 2013). "Who, Exactly, Is A Gringo?". NPR. Archived from the original on December 22, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ "Gringo". American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ "Is 'Irregardless' a Real Word?". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on May 16, 2022. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ "Definition: irregardless". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on May 8, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ "Prepositions, Ending a Sentence with". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on April 10, 2024. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ Thompson, Oliver (February 28, 2024). "Why Merriam-Webster says it's OK to end a sentence in a preposition". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on March 13, 2024. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ Fogarty, Mignon (2011). The Ultimate Writing Guide for Students. New York: Henry Holt & Company. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-8050-8944-8.

- ^ a. Jackson, Janice Eurana (1998). Linguistic aspect in African-American English-speaking children: An investigation of aspectual "be" (Dissertation thesis). University of Massachusetts Amherst. ISBN 978-0-591-96032-7. ProQuest 304446674. Archived from the original on July 8, 2024. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

b. "African American English". PBS. Archived from the original on September 30, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2024. - ^ a b c Mikkelson, Barbara (June 13, 2008). "420". Snopes. Archived from the original on October 19, 2009. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ^ "Title 11. Of Crimes Against the Public Peace [403 - 420.1]: 420". leginfo.legislature.ca.gov. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ a b O'Conner & Kellerman 2009, pp. 77, 145.

- ^ Bratcher, Dennis (December 3, 2007). "The Origin of "Xmas"". CRI / Voice, Institute. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- ^ "X". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. 1921. doi:10.1093/OED/9635674512. Retrieved July 7, 2024. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Xmas". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2020. doi:10.1093/OED/7290422930. Retrieved July 7, 2024. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b Harper, Douglas (2010). "Crap". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ "Crap". American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2001. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Sheidlower, Jesse (2009). "Introduction". The F-Word (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539311-8.

- ^ a b c a. Mikkelson, Barbara (July 8, 2007). "What the Fuck?". Snopes. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

b. Mikkelson, Barbara (July 9, 2007). "Pluck Yew". Snopes. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2011. - ^ Sheidlower, Jesse (Autumn 1998). "Revising the F-Word". Verbatim: The Language Quarterly. 23 (4): 18–21.

- ^ a b Kelly, Henry Ansgar (September 1994). "Rule of Thumb and the Folklaw of the Husband's Stick" (PDF). Journal of Legal Education. 44 (3): 341–65. JSTOR 42893341. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ O'Conner & Kellerman 2009, pp. 123–126.

- ^ Mikkelson, David (March 11, 2001). "Why Are Blue Laws Called 'Blue Laws'?". Snopes. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Cheung, Iva (May 25, 2015). "Sacré Bleu! Why Is Blue the Most Profane Color?". Slate. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Brians, Paul (2011). "Common Errors in English Usage – Ye". Common Errors in English Usage. Washington State University. Archived from the original on May 31, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2001–2010). "Etymology Online". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- ^ Hill, Will (30 June 2020). "Chapter 25: Typography and the printed English text" (PDF). The Routledge Handbook of the English Writing System. Taylor & Francis. pp. 6, 15. ISBN 978-0-367-58156-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2022.

- ^ Coe & Coe (2013), Crossing the Language Barrier.

- ^ Zimmer, Ben (April 23, 2018). "'Wop' Doesn't Mean What Andrew Cuomo Thinks It Means". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (October 25, 2017). "Ingenious Trifling". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ "wop". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins.

- ^ Farrell, Graham; Tilley, Nick; Tseloni, Andromachi (September 2014). "Why the Crime Drop?" (PDF). Crime and Justice. 43 (1): 421–490. doi:10.1086/678081. S2CID 145719976. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ Tonry, Michael (January 2014). "Why Crime Rates Are Falling Throughout the Western World, 43 Crime & Just. 1 (2014)". Crime & Just: 1–2. Archived from the original on May 23, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ Gramlich, John (November 20, 2020). "What the data says (and doesn't say) about crime in the United States". Pew Research. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ "Gun homicides steady after decline in '90s; suicide rate edges up". Pew Research. October 21, 2015. Archived from the original on September 3, 2019. Retrieved September 4, 2019.

- ^ Gershoff, Elizabeth T. (Spring 2010). "More Harm Than Good: A Summary of Scientific Research on the Intended and Unintended Effects of Corporal Punishment on Children". Law & Contemporary Problems. 73 (2). Duke University School of Law: 31–56. Archived from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved December 18, 2024.

- ^ Gershoff, Elizabeth T.; Grogan-Kaylor, Andrew (2016). "Spanking and Child Outcomes: Old Controversies and New Meta-Analyses" (PDF). Journal of Family Psychology. 30 (4): 453–469. doi:10.1037/fam0000191. PMC 7992110. PMID 27055181. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 18, 2024. Retrieved December 18, 2024.

- ^ Afifi, T. O.; Mota, N. P.; Dasiewicz, P.; MacMillan, H. L.; Sareen, J. (2 July 2012). "Physical Punishment and Mental Disorders: Results From a Nationally Representative US Sample". Pediatrics. 130 (2). American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP): 184–192. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2947. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 22753561. S2CID 21759236.

- ^ Gershoff, E. T. (2018). "The strength of the causal evidence against physical punishment of children and its implications for parents, psychologists, and policymakers" (PDF). American Psychologist. 73 (5): 626–638. doi:10.1037/amp0000327. PMC 8194004. PMID 29999352. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2024. Retrieved December 18, 2024.

- ^ a. Benedictus, Leo (March 23, 2015). "Gum control: how Lee Kuan Yew kept chewing gum off Singapore's streets". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

b. Rajah, Jothie (January 1, 2014). "Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore's Rule of Law". Law Text Culture. 18 (1): 135–165. doi:10.14453/ltc.558. ISSN 1322-9060. Archived from the original on March 10, 2023. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

c. Brown, Lauren (March 1, 2012). "How To Travel In Singapore Without Getting Caned". Business Insider. Archived from the original on October 21, 2022. Retrieved July 9, 2022. - ^ Gilsinan, Kathy (2014-05-12). "Interpol at 100: Does the World's Police Force Work?". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 16, 2023. Retrieved 2022-04-02.

- ^ Lee, Michael. "Interpol hopes physical border security will solve virtual borders". ZDNet. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved 2022-04-07.

- ^ Brunvand, Jan Harold (2012-01-01). Encyclopedia of Urban Legends. ABC-CLIO. p. 288. ISBN 978-1-59884-720-8. Archived from the original on January 21, 2023. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- ^ Boks, Ed (2010-10-06). "The truth about black cats and Halloween". The Daily Courier. Prescott, Arizona. Archived from the original on 2012-03-22. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- ^ a. Sparks, Preston; Cox, Timothy (November 17, 2008). "Missing persons usually found". Augusta Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved May 21, 2011.

b. "FAQs: Question: Do you need to wait 24 hours before reporting a person missing?". National Missing Persons Coordination Center, Australian Federal Police. Archived from the original on September 23, 2008. Retrieved May 22, 2011.

c. Vongkiatkajorn, Kanyakrit. "NYPD: How The Police Handles Missing Persons Cases". NYCity News Service. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved June 25, 2022. - ^ "Report or find a missing person". Gov.uk. June 3, 2013. Archived from the original on January 22, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ "Why the first 72 hours in a missing persons investigation are the most critical, according to criminology experts". ABC News. Archived from the original on March 12, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ Douglas Abrams, References to Television Shows in Judicial Opinions and Written Advocacy (Part I), 75 J.Mo.B. 25, 27 (2019).

- ^ Immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than U.S.-born Americans, studies find MARCH 8, ALL THINGS CONSIDERED Jasmine Garsd https://www.npr.org/2024/03/08/1237103158/immigrants-are-less-likely-to-commit-crimes-than-us-born-americans-studies-find Archived May 16, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Light, Michael T.; He, Jingying; Robey, Jason P. (2020). "Comparing crime rates between undocumented immigrants, legal immigrants, and native-born US citizens in Texas". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (51): 32340–32347. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11732340L. doi:10.1073/pnas.2014704117. PMC 7768760. PMID 33288713.

- ^ The mythical tie between immigration and crime Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) Krysten Crawford July 21, 2023 https://siepr.stanford.edu/news/mythical-tie-between-immigration-and-crime Archived May 21, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Willingham, AJ (September 6, 2018). "The First Amendment doesn't guarantee you the rights you think it does". CNN. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ McGregor, Jena (August 8, 2017). "The Google memo is a reminder that we generally don't have free speech at work". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ Dunn, Christopher (April 28, 2009). "Column: Applying the Constitution to Private Actors (New York Law Journal)". New York Civil Liberties Union. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Berman-Gorvine, Martin (May 19, 2014). "Employer Ability to Silence Employee Speech Narrowing in Private Sector, Attorneys Say". Bloomberg BNA. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ Imwinkelried and Blinka, Criminal Evidentiary Foundations, 2d ed. (Lexis 2007) ISBN 978-1-4224-1741-6 at 620.

- ^ "Can a case be dismissed if a person is not read his/her Miranda rights?". Patrick Barone. September 10, 2021. Archived from the original on July 14, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- ^ "Snopes on Entrapment". Snopes.com. March 12, 1998. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- ^ Larson, Aaron. "What is Entrapment". ExpertLaw. Archived from the original on October 26, 2017. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ Timm, Trevor (2012-11-02). "It's Time to Stop Using the 'Fire in a Crowded Theater' Quote". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on August 15, 2023. Retrieved 2020-06-20.

- ^ Volokh, Eugene (2015-05-11). "Shouting fire in a crowded theater". Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 20, 2023. Retrieved 2020-06-20.

- ^ "5 Military Myths Busted". Military.com. May 8, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2024.

- ^ a. Powers, Rod (November 24, 2019). "Can a Judge Order Someone to Join the Military or Go to Jail?". The Balance. Archived from the original on December 30, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

b. Schogol, Jeff (February 3, 2006). "Judge said Army or jail, but military doesn't want him". Stars and Stripes. Archived from the original on December 30, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

c. Garnett, Benjamin (January 21, 2022). "Guest columnist: Time to join military or go to jail is over". The State Journal (Kentucky). Retrieved June 23, 2024. - ^ Mikkelson, David (October 30, 2014). "Death Row Inmate Asks for a Child As His Last Meal, Texas DOC Plan to Grant Request?". Snopes. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Beam, Christopher (November 10, 2009). "I'll Have 24 Tacos and the Filet Mignon". Slate. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Paul E. Richardson, "The hot line (is a Hollywood myth)", in: Russian Life, September/October issue 2009, pp. 50–59.

- ^ Clavin, Tom (June 18, 2013). "There Never Was Such a Thing as a Red Phone in the White House". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on November 10, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ "Jimi Hendrix cleared of blame for UK parakeet release". BBC. December 13, 2019. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ Kaplan, Fred (February 11, 2021). "How Close Did the Capitol Rioters Get to the Nuclear "Football"?". Slate. Archived from the original on May 14, 2024. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Dobbs, Michael (October 2014). "The Real Story of the "Football" That Follows the President Everywhere". Smithsonian. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Craw, Victoria (January 4, 2018). "The nuclear button: Real or fake news?". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Pogash, Carol (November 23, 2003). "Myth of the 'Twinkie defense'". San Francisco Chronicle. p. D-1. Archived from the original on June 11, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

The "Twinkie defense" is so ingrained in our culture that it appears in law dictionaries, in sociology textbooks, in college exams and in more than 2, 800 references on Google. Only a few of them call it what it is: a myth.

- ^ Mikkelson, David (October 30, 1999). "The Twinkie Defense: Debunking the Myths and Misinformation". Retrieved June 18, 2024.

"Twinkie defense" is now a widespread and commonly-recognized term. It is also a term based on something that never happened.

- ^ Colleen Long (May 5, 2016). "Cops seek killer of man who washed ashore in 'cement shoes'". CBS 3 Philadelphia. Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ^ "'Cement shoes' found on NYC corpse". BBC News. May 5, 2016. Archived from the original on April 3, 2023. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "Après deux ans de polémique, l'État "enterre" le général Bigeard". France 24 (in French). November 20, 2012. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara (June 9, 1999). "Have People Been Buried Alive?". Snopes.

- ^ Slominski, Elena (August 29, 2023). "Life of the death system: shifting regimes, evolving practices, and the rise of eco-funerals". Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy. 19 (1): 7. Bibcode:2023SSPP...1943779S. doi:10.1080/15487733.2023.2243779.

- ^ Chiappelli, Jeremiah; Chiappelli, Ted (December 2008). "Drinking Grandma: The Problem of Embalming". Journal of Environmental Health. 71 (5): 25–26. JSTOR 26327817. PMID 19115720.

- ^ Knowles, Elizabeth (October 26, 2006). What They Didn't Say: A Book of Misquotations. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-150054-1. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ "200th anniversary of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein". Australian National University. September 12, 2018. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ Evans, Bergen (1962). Comfortable Words. New York City: Random House.

All dictionaries now recognize "a Frankenstein" as any monstrous creation that threatens to destroy its creator.

- ^ Garner, Bryan A. (1998). A dictionary of modern American usage. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507853-4.

Today this ubiquitous usage must be accepted as standard

- ^ Haglund, David (January 31, 2013). "Did Hemingway Really Write His Famous Six-Word Story?". Slate. Retrieved June 23, 2024.

- ^ Churchwell, Sarah (June 23, 2019). "For sale, baby shoes, never worn — the myth of Ernest Hemingway's short story". The Times. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- ^ a. Brinkmann, Vinzenz (2008). "The Polychromy of Ancient Greek Sculpture". In Panzanelli, Roberta; Schmidt, Eike D.; Lapatin, Kenneth (eds.). The Color of Life: Polychromy in Sculpture from Antiquity to the Present. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum and the Getty Research Institute. pp. 18–39. ISBN 978-0-89236-918-8.

b. Gurewitsch, Matthew (July 2008). "True Colors: Archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann insists his eye-popping reproductions of ancient Greek sculptures are right on target". Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

c. Prisco, Jacopo (November 30, 2017). "'Gods in Color' returns antiquities to their original, colorful grandeur". CNN style. Archived from the original on June 17, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2018. - ^ Talbot, Margaret (October 22, 2018). "The Myth of Whiteness in Classical Sculpture". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 11, 2023. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ Whiddington, Richard (February 20, 2024). "Art Bites: Michelangelo's Poem About How Much It Sucked to Paint the Sistine Chapel". Artnet. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ "Michelangelo". thesistinechapel.org. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Fineman, Mia (June 8, 2005). "The Most Famous Farm Couple in the World: Why American Gothic still fascinates Archived December 6, 2018, at the Wayback Machine". Slate.

- ^ "About This Artwork: American Gothic". The Art Institute of Chicago. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ Sorensen, Jon (February 10, 2014). "Did the Vatican Outlaw "The Devil In Music?"". Catholic Answers. Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ Smith 1979, pp. 69–70.

- ^ a b Drabkin, William (2001). "Tritone". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.28403. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved May 23, 2024. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Solomon 1995, p. 587.

- ^ "Was Mozart actually poisoned by Salieri?". Classic fm. Archived from the original on April 3, 2023. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ a. Wolff, Christoph (2001). "Bach. III. 7. Johann Sebastian Bach. Works". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

b. Williams, Peter F. (2007). J.S. Bach: A Life in Music. Cambridge University Press. p. 158.

c. Schulenberg, David (2006). The Keyboard Music of J.S. Bach. p. 448.