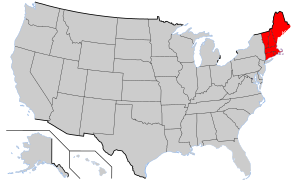

Politics of New England

The politics of New England has long been defined by the region's political and cultural history, demographics, economy, and its loyalty to particular U.S. political parties. Within the politics of the United States, New England is sometimes viewed in terms of a single voting bloc. All of the twenty-one congressional districts in New England are currently represented by Democrats. In the Senate, nine Democrats, two Independents (both of whom caucus with Democrats), and one Republican represent New England. The Democratic candidate has won a plurality of votes in every State in New England in every presidential election since 2004, making the region considerably more Democratic than the rest of the nation.

Same-sex marriage had been permitted in all New England states before the U.S. Supreme Court case Obergefell v. Hodges made it legal nationwide. Rhode Island was the final New England state to legalise the practice in May 2013.[1]

The national U.S. movement against nuclear power had its roots in New England in the 1970s. In 1974, activist Sam Lovejoy toppled a weather tower at the site of the proposed Montague Nuclear Power Plant in Western Massachusetts.[2] The movement "reached critical mass" with the arrests at Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant on May 1, 1977, when 1,414 anti-nuclear activists from the Clamshell Alliance were arrested at the Seabrook site. Harvey Wasserman, a Clamshell spokesman at Seabrook, and Frances Crowe of Northampton, an American Friends Service Committee member, played key roles in the movement.[2]

Notable laws and political movements

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2013) |

The New England states abolished the death penalty for robbery and burglary in the 19th century, before much of the rest of the United States.[citation needed] New Hampshire was the final New England state to outlaw the practice, doing so in 2019.[3] Although New Hampshire currently has one death row inmate, it has not held an execution since 1939.[4]

Connecticut and Rhode Island were the only states in the union not to ratify the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, also known as prohibition.[5]

New Hampshire has no seatbelt law for persons over 18 years of age,[6] no helmet law for motorcyclists,[7] no mandatory auto-insurance law,[8] and has neither an income tax nor a sales tax.[9]

Vermont, Maine and New Hampshire allow both the open and concealed carrying of a firearm without a permit.[10][11]

Massachusetts passed a ballot initiative (question 3) in the November 2012 election that legalized medical marijuana, effective January 1, 2013. Only people with debilitating diseases such as cancer, Parkinson's disease, or Alzheimer's can obtain a medical marijuana card. Massachusetts became the 18th state in the US to legalize the medical use of marijuana.[12] Similar laws are also in place in every state in New England aside from New Hampshire.[13]

Same-sex marriage

[edit]Same-sex marriage had been legalized in all of the New England states: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont, before it became legal nationwide in Obergefell v. Hodges. The New England region has been noted for being the center of the same-sex marriage movement in the United States,[14] with the region having among the most widespread and earliest legal support of any region. In 2004, Massachusetts became the first state in the United States to legalize same-sex marriage,[15] to be followed by three more states between October 2008 and June 2009. This followed Vermont being the first-in-the-nation with civil unions in 2000.[16] Before the 2012 election, California (2008), Iowa (2009), New York (2011) and the District of Columbia (2010) had been the only U.S. jurisdictions outside New England to have performed same-sex marriages, though same-sex marriages in California had been halted following the passage of Proposition 8.

The legalization of same-sex marriage was part of a campaign which began in November 2008, called Six by Twelve, and was organized by the Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders (GLAD) to legalize same-sex marriage in all six New England states by 2012.[17][18]

The region holds a number of firsts on same-sex marriage: Vermont was the first state to enact it through legislative means and not because of a judicial ruling,[19][20] and Maine was the first state to have a governor sign a same-sex marriage bill that was not the result of a court decision.[21] However, this law was repealed through a people's veto (53% voted to ban it versus 47% who voted to legalize it), but three years later, on November 6, 2012, the question was put to voters a second time, and the electorate voted 53–47 in support of same-sex marriage. As a result, Maine became one of three first US states to approve same-sex marriage at the ballot box, along with Washington and Maryland.

With Rhode Island legalizing same-sex marriage, all New England states allowed the practice. There have been numerous reasons given for why New England has found such strong legal recognition for same-sex marriages in comparison to the rest of the United States, including low religiosity, high educational attainment, strong social libertarianism, a long history of open same-sex relationships (including Boston marriages), and a general independent streak in New England culture.[14][22][23][24][25]

Anti-nuclear movement

[edit]There were four targets of the anti-nuclear movement since 1974. As a result, Montague Nuclear was cancelled. Yankee Rowe closed prematurely for engineering inadequacies. Vermont Yankee was closed because it became uncompetitive. Seabrook remains operational.

Montague Nuclear Power Plant

[edit]On February 22, 1974, Sam Lovejoy took a crowbar to the weather-monitoring tower which had been erected at the Montague Nuclear Power Plant site. Lovejoy fell 349 feet (106 m) from the 550 feet (170 m) tower. He turned himself in to the local police. He presented a statement in which he took responsibility for the action. Lovejoy's action galvanized local public opinion against the plant.[26][27] The Montague nuclear power plant proposal was canceled in 1980,[28] after $29 million was spent on the project.[26]

Seabrook

[edit]Seabrook power plant was proposed as a twin-reactor plant in 1972, at an estimated cost of $973 million. It received a commercial license in March 1990 for one reactor which cost $6.5 billion.[29] Over a period of thirteen years more than 4,000 citizens, many associated with the Clamshell Alliance anti-nuclear group, committed non-violent civil disobedience at Seabrook:[30]

- August 1, 1976: 200 residents rallied at the future Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant site in New Hampshire, and 18 were arrested for criminal trespass.[30]

- August 22, 1976: 188 activists from New England were arrested at the Seabrook site.[30][31]

- May 2, 1977: 1,414 protesters were arrested at Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant.[2][32][33] The protesters who were arrested were expected to be "released on their own recognizance", but this did not happen. Instead, they were charged with criminal trespass and asked to post bail ranging from $100 to $500. They refused and were then held in five national guard armories for 12 days. The Seabrook conflict, and role of New Hampshire Governor Meldrim Thomson, received much national media coverage.[34]

- May 13, 1977: 550 protestors were freed after being detained for thirteen days.[citation needed]

- June 1978: some 12,000 people attended a protest at Seabrook.[32][33]

- May 25–27, 1980: Police use tear gas, riot sticks and dogs to drive 2,000 demonstrators away from the Seabrook site.[35]

- May 24, 1986: 74 anti-nuclear demonstrators were arrested in protests.[36][37]

- October 17, 1988: 84 people were arrested at the Seabrook plant.[38]

- June 5, 1989: hundreds of demonstrators protested against the plant's first low-power testing, and the police arrested 627 people for trespassing; two state legislators, one from Massachusetts and one from New Hampshire, protested.[30][39]

Yankee Rowe

[edit]The New England Coalition (NEC) is an educational non-profit organization based in Brattleboro, Vermont. Historically, it has been part of the anti-nuclear movement in the United States.[40] The NEC is primarily concerned with legal action more than protests. It was involved in both legal action and protests about the Yankee Rowe Nuclear Power Plant prior to its shut down in 1992, and has been involved in legal action and protests over extending the license to operate at the Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant.

Vermont Yankee

[edit]In February 2010, the Vermont Senate voted 26 to 4 against allowing the PSB to consider re-certifying the Vermont Yankee Nuclear Plant after 2012, citing radioactive tritium leaks, misstatements in testimony by plant officials, a cooling tower collapse in 2007, and other problems.[41] In January 2012, Entergy won a court case to invalidate the state's veto power on continued operation.[42]

There were a number of anti-nuclear protests about Vermont Yankee since the 1970s. These included protests following the Japanese Fukushima nuclear disaster in March 2011 and on the date of the original operating license expiry in March 2012. On August 28, 2013, the company said economic factors, notably the low cost of electricity caused by cheap natural gas, would result in the company's decommissioning the plant in the fourth quarter of 2014.[42]

Attempts at secession

[edit]Hartford Convention

[edit]The Hartford Convention was a series of meetings dating from December 15, 1814, to January 5, 1815, taking place in Hartford, Connecticut. They were led by various New England leaders leaders of the Federalist Party, and discussed their grievances concerning the War of 1812 and the other political problems stemming from the federal government's increasing power. One of the most notable propositions during the Hartford Convention was the idea of secession from the United States.[43]

The New England Independence Campaign

[edit]The New England Independence Campaign (NEIC) is a big tent political advocacy organization founded in 2014 by Alex Gilbert. They cite issues such as the unfair balance of payments between states like Connecticut and Massachusetts and the federal government[44] as reason for secession. Other key platform issues include non-interventionism, political decentralization, reproductive rights, environmentalism, responsible gun ownership, and advocacy for electoral reform, including multi-party democracy and ranked voting.[1] The NEIC has historically clashed with neo-Nazi groups like NSC-131.[45] Despite being nominally non-partisan, it draws most of its support from progressives, libertarians, and moderates.

New England Autonomy

[edit]The New England Autonomy Movement (NEAM) is a political advocacy organization founded in 2024. Key platform issues include economic independence, reproductive rights, environmentalism, and advocacy for electoral reform, including multi-party democracy and ranked voting.[2] The NEAM is a distinct organization, but shares significant membership with the NEIC. They believe in increasing state's autonomy, self-sufficiency, and infrastructure in anticipation of future attempts to achieve regional independence.[46]

The People's Initiative of New England

[edit]The People's Initiative of New England (PINE) is a subgroup of the Nationalist Social Club-131 founded in July 2023. Although they cite more issues on their publications, they mainly focus on issues such as; the nuclear family, the fentanyl crisis, housing, ongoing immigration, and a depleting regional identity. Multiple sources have noted overt racism, antisemitism, homophobia, and transphobia within their rhetoric, including the Southern Poverty Law Center[47] and the Anti-Defamation League.[48] They often do flag waving rallies to spread awareness for their issues and to help preserve regional identity, as well as attending local meetings of elected officials.[49] In February 2024, the group demonstrated in front of Governor Maura Healey's residence in response to civil charges filed by the Massachusetts Attorney General regarding the group's efforts to "disrupt public peace and safety".[50]

See also

[edit]- Elections in New England

- Politics of Vermont

- Politics of New Hampshire

- Politics of Maine

- Politics of Massachusetts

- Politics of Connecticut

- Politics of Rhode Island

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Same-sex marriages begin in R.I., Minnesota". Boston Globe. August 1, 2013. Archived from the original on August 5, 2013. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ^ a b c Michael Kenney. Tracking the protest movements that had roots in New England The Boston Globe, December 30, 2009.

- ^ "Death Penalty Information Center" Archived 2015-05-23 at the Wayback Machine, Deathpenaltyinfo.org. Retrieved July 19, 2006.

- ^ "Supreme Court Lifts Order Blocking Connecticut Execution", Fox News, January 29, 2005, Retrieved July 19, 2006, "New Hampshire has not executed anyone since 1939 and has no one on death row. New Hampshire outlawed capital punishment in 2019 Seven inmates are waiting to die in Connecticut, which conducted New England's last execution in 1960."

- ^ "CONNECTICUT BALKS AT PROHIBITION; Senate Rejects Federal Amendment—First State to Failto Ratify" (PDF). The New York Times. 1919-02-05.

- ^ State Seat Belt Laws. Ghsa.org. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ New Hampshire Motorcycle Helmet Law. Bikersrights.com. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ State Insurance Laws Archived 2013-12-15 at the Wayback Machine. Autoinsuranceremedy.com. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ Does NH have an Income Tax or Sales Tax? | Frequently Asked Questions | NH Department of Revenue Administration. Nh.gov. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ State Information For New Hampshire Archived 2011-11-30 at the Wayback Machine. OpenCarry.org. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ State Information For Vermont Archived 2013-02-13 at the Wayback Machine. OpenCarry.org. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ "Return of Votes For Massachusetts State Election November 6, 2012" (PDF). Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- ^ "18 Legal Medical Marijuana States and DC Laws, Fees, and Possession Limits". procon.org. Archived from the original on 2017-05-07. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- ^ a b A Push Is On for Same-Sex Marriage Rights Across New England, New York Times, April 4, 2009

- ^ Burge, Kathleen (November 18, 2003). "SJC: Gay marriage legal in Mass". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Vermont legalizes gay marriage[permanent dead link], Burlington Free Press, April 7, 2009

- ^ 'Gay marriage' bill passes N.H. Senate, Baptist Press, April 24, 2009

- ^ 6x12: Half-way There and Going Strong! Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, GLAD, April 14, 2009

- ^ "Vt. legalizes same-sex marriage". The Burlington Free Press. 2009-04-07. Retrieved 2009-04-07. [dead link]

- ^ Goodnough, Abby (2009-04-07). "Vermont Legislature Makes Same-Sex Marriage Legal". The New York Times. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ Russel, Jenna (2009-05-06). "Gay marriage law signed in Maine, advances in N.H". Boston.com. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ^ Gay Marriage Advances in Maine, The New York Times, Abby Goodnough and Katie Zezima, May 5, 2009

- ^ Lin, Joanna (2009-03-16). "New England surpasses West Coast as least religious region in America, study finds". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ New England leads on same-sex marriage, NECN, May 7, 2009

- ^ N.E.'s identity bolsters gay marriage tolerance, The Boston Globe, Jenna Russell, May 11, 2009

- ^ a b Utilities Drop Nuclear Power Plant Plans Ocala Star-Banner, January 4, 1981.

- ^ No nukes by Anna Gyorgy pp. 393–394.

- ^ Some of the Major Events in NU's History Since the 1966 Affiliation Archived 2013-12-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 30 years later, another nuclear struggle looms Archived 2012-09-09 at archive.today The Daily News, April 30, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Gunter, Paul. Clamshell Alliance: Thirteen Years of Anti-Nuclear Activism at Seabrook, New Hampshire, U.S.A.Ecologia Newsletter, January 1990 Issue 3.

- ^ Seabrook, NH Nuclear Plant Occupation Page

- ^ a b Williams, Estha. Nuke Fight Nears Decisive Moment Archived 2014-11-29 at the Wayback Machine Valley Advocate, August 28, 2008.

- ^ a b Williams, Eesha. Wikipedia distorts nuclear history Valley Post, May 1, 2008.

- ^ William A. Gamson and Andre Modigliani. Media Coverage and Public Opinion on Nuclear Power[permanent dead link], American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 95, No. 1, July 1989, p. 17.

- ^ Hartford Courant

- ^ Anti-Nuclear Protesters Freed in New Hampshire

- ^ New Hampshire / Anti-Nuclear Demonstration

- ^ 84 Arrested in Protest At the Seabrook Plant

- ^ Gold, Allan R. Hundreds Arrested Over Seabrook Test New York Times, June 5, 1989.

- ^ New England Coalition.

- ^ Wald, Matthew L., Vermont Senate Votes to Close Nuclear Plant The New York Times, February 24, 2010.

- ^ a b "Entergy to Close, Decommission Vermont Yankee" (Press release). PR Newswire.

- ^ "Hartford Convention | Federalist Party, Secession, New England | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ "Balance of Payments Portal". 7 September 2018.

- ^ "NEIC Official Statement Regarding Recent Extremist Groups' Social Media Posts – New England Independence Campaign".

- ^ "New England Autonomy". New England Autonomy. Retrieved 2025-01-14.

- ^ "Nationalist Social Club (NSC-131)".

- ^ "Nationalist Social Club (NSC-131) | ADL".

- ^ Initiative, The People’s (2023-07-28). "Introduction". PINE Updates. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ "Neo-Nazis Swarm Home of New England Governor". Rolling Stone. 12 February 2024.