Politics of the European Union

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

The political structure of the European Union (EU) is similar to a confederation, where many policy areas are federalised into common institutions capable of making law; the competences to control foreign policy, defence policy, or the majority of direct taxation policies are mostly reserved for the twenty-seven state governments (the Union does limit the level of variation allowed for VAT). These areas are primarily under the control of the EU's member states although a certain amount of structured co-operation and coordination takes place in these areas. For the EU to take substantial actions in these areas, all Member States must give their consent. Union laws that override State laws are more numerous than in historical confederations; however, the EU is legally restricted from making law outside its remit or where it is no more appropriate to do so at a state or local level (subsidiarity) when acting outside its exclusive competences. The principle of subsidiarity does not apply to areas of exclusive competence.

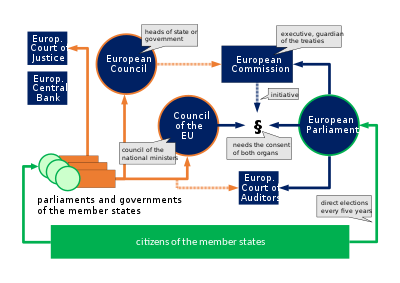

The common institutions mix the intergovernmental and supranational (similar to federal) aspects of the EU. The EU treaties declare the Union to be based on representative democracy, and direct elections take place in the European Parliament. The Parliament, together with the Council, form the legislative arm of the EU. The council is composed of state governments, thus representing the intergovernmental nature of the EU. Laws are proposed by the European Commission which is appointed by and accountable to the Parliament and Council although it has very few executive powers.

Although direct elections take place every five years, there are no cohesive political parties in the national sense. Instead, there are alliances of ideologically associated parties who sit and vote together in Parliament. The two largest parties are the European People's Party (centre-right, mostly Christian Democrat) and the Party of European Socialists (centre-left, mostly Social Democrat) with the former forming the largest group in Parliament since 1999. As well as there being left and right dividing lines in European politics, there are also divides between those for and against European integration (Pro-Europeanism and Euroscepticism) which shapes the continually changing nature of the EU which adopts successive reforming treaties. The latter was a significant political force in the United Kingdom in the decades and years before leaving the Union, and some member states are less integrated than others due to legal opt-outs.

Legal basis

[edit]

- The functioning of the Union shall be founded on representative democracy.

- Citizens are directly represented at Union level in the European Parliament. Member States are represented in the European Council by their Heads of State or Government and in the Council by their governments, themselves democratically accountable either to their national Parliaments, or to their citizens.

- Every citizen shall have the right to participate in the democratic life of the Union. Decisions shall be taken as openly and as closely as possible to the citizen.

- Political parties at European level contribute to forming European political awareness and to expressing the will of citizens of the Union.

The democratic legitimation of the European Union rests on the Treaty System. The move toward unification first arose in the Kellogg-Briand Pact in 1928, which gained adherent countries during negotiations and took on a theme of integration for the achievement of peace between the Great Powers.[1] After the Second World War, European society sought to end conflict permanently between states, seeing the rivalry between France and Germany as the most worrying example. In the spirit of the Marshall Plan[how?], those two states signed the Treaty of Paris in 1951, establishing the European Coal and Steel Community. Since then, the Treaty of Paris, which focused on price setting and competition for purposes of a common market, has been superseded. The legal basis for the European Community now rests on two treaties: the Treaty of Rome of 1958; and the Treaty of Maastricht of 1992. The various additions and modifications of treaties has led to a patchwork of policy and planning, which contributes to the unwieldiness of the EU. The pastiche of treaties, and not a single actualising charter of government, form the constitutional basis of the European Union. This ambiguity is what critics call a primary cause of "democratic deficit."

The EU itself is a legal personality and a set of governing institutions empowered by the treaties. However sovereignty is not invested in those institutions, it is pooled with ultimate sovereignty resting with the state governments. Yet in those areas where the EU has been granted competences, it does have the power to pass binding and direct laws upon its members.

Competences

[edit]The competences of the European Union stem from the original Coal and Steel Community, which had as its goal an integrated market. The original competences were regulatory in nature, restricted to matters of maintaining a healthy business environment. Rulings were confined to laws covering trade, currency, and competition. Increases in the number of EU competences result from a process known as functional spillover. Functional spillover resulted in, first, the integration of banking and insurance industries to manage finance and investment. The size of the bureaucracies increased, requiring modifications to the treaty system as the scope of competences integrated more and more functions. While member states hold their sovereignty inviolate, they remain within a system to which they have delegated the tasks of managing the marketplace. These tasks have expanded to include the competences of free movement of persons, employment, transportation, and environmental regulation.

|

|

| |||||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

Law

[edit]Types of legislation

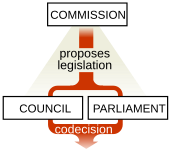

[edit]The Ordinary Legislative Procedure (OLP) is the formal, main legislative procedure. In OLP, the European Parliament (EP) and the Council act in much the same way as a bicameral congress, such as the British Upper and Lower Houses or the American Congress. The co-decision rule in Maastricht, and the subsequent Lisbon Treaty, ultimately gave the EP and the Council equal weight and formalised OLP as the main legislative procedure. It also gives the EP veto power. The two legislative powers of the OLP are directives and regulations. A directive requires the member states to pass the new law individually, a process called "transposition." The difference in the timing of completing transposition is the "democratic deficit." A regulation acts on all the member states at once and is effective immediately.

The other legislation option is the Special Legislative Procedure (SLP). The SLP consists of the passing of laws proposed by member states, the Central Bank or Investment Bank, or the Court of Justice. Judicial activism—the interpretation of the spirit of law rather than the letter of law—is handled by the SLP. The procedure is discussed either in the EP with consultation with the council, or in the council with participation of the EP. In other words, the consultative role stops short of the equal weight given to both the EP and the council. While provided for in the treaties, the SLP is not as formal as the OLP, relying less on the hierarchical structure. This lends more credence to Kleine's argument of the contrariness of the EU's agenda-setting procedure.[3]

Mechanics of legislation

[edit]In the OLP, there are four types of rulings: Regulations, Directives, Decisions, and Recommendations. Decision-making is shared by the European Parliament and the council, which are equally weighted. Regulations are binding on all member states effective immediately. Directives are binding on all member states, but the implementation is left up to the national courts in a process called transposition. However, since member states set their own timelines for transposition, there is a democratic deficit between states. Decisions are binding on non-state litigants to whom they are addressed.[4] Recommendations are intended to guide legal judgments and are non-binding, similar to opinions.

In the SLP, the council is the sole ruling body. The European Parliament is involved strictly in a consultative role and can be ignored.

Member states

[edit]There are twenty-seven member states who have conferred powers upon the EU institutions (other countries are tied to the EU in other ways). In exchange for conferring competences, EU states are assigned votes in the Council, seats in Parliament and a European Commissioner among other things. The internal government of member states vary between presidential systems, monarchies, federations, and microstates however all members must respect the Copenhagen criteria of being democratic, respecting human rights and having a free market economy. Members joined over time, starting with the original six in 1958 and more members joining in the near future.

Some member states are outside certain areas of the EU, for example the eurozone is composed of only 20 of the 27 members and the Schengen Agreement currently includes only 23 of the EU members. However, the majority of these are in the process of joining these blocs. A number of countries outside the EU are involved in certain EU activities such as the euro, Schengen, single market or defence.[5][6][7]

Institutions

[edit]

The primary institutions of the European Union are the European Commission, the Council of the European Union (Council), the European Council and the European Parliament.

The ordinary legislative procedure, applies to nearly all EU policy areas. Under the procedure, the Commission presents a proposal to Parliament and the council. They then send amendments to the Council which can either adopt the text with those amendments or send back a "common position". That proposal may either be approved or further amendments may be tabled by the Parliament. If the Council does not approve those, then a "Conciliation Committee" is formed. The committee is composed of the Council members plus an equal number of MEPs who seek to agree a common position. Once a position is agreed, it has to be approved by Parliament again by an absolute majority.[8][9] There are other special procedures used in sensitive areas which reduce the power of Parliament.

Parliament

[edit]The European Parliament shares the legislative and budgetary authority of the Union with the council. Its 705 members are elected every five years by universal suffrage and sit according to political allegiance. It represents all European Citizens in the EU's legislative process, in contrast to the council, which represents the Member States. Despite forming one of the two legislative chambers of the Union, it has weaker powers than the Council in some limited areas, and does not have legislative initiative. It does, however, have powers over the Commission which the Council does not.[10] The powers of the Parliament have increased substantially over the years, and in nearly all areas it now has equal power to the council.

European Council

[edit]

The European Council is the group of heads of state or government of the EU member states. It meets four times a year to define the Union's policy agenda and give impetus to integration. The President of the European Council is the person responsible for chairing and driving forward the work of the institution, which has been described as the highest political body of the European Union.[11]

Council of the European Union

[edit]The Council of the European Union (informally known as the Council of Ministers or just the council) is a body holding legislative and some limited executive powers and is thus the main decision-making body of the Union. Its Presidency rotates between the states every six months. The council is composed of twenty-eight national ministers (one per state). However, the Council meets in various forms depending upon the topic. For example, if agriculture is being discussed, the council will be composed of each national minister for agriculture. They represent their governments and are accountable to their national political systems. Votes are taken either by majority or unanimity with votes allocated according to population.[12]

Commission

[edit]The European Commission is composed of one appointee from each state, currently twenty-seven, but is designed to be independent of national interests. The body is responsible for drafting all law of the European Union and has a monopoly over legislative initiative. It also deals with the day-to-day running of the Union and has a duty to uphold the law and treaties (in this role it is known as the "Guardian of the Treaties").[13]

The commission is led by a President who is nominated by the council (in practice the European Council) and approved by Parliament. The remaining twenty-seven Commissioners are nominated by member-states, in consultation with the President, and has their portfolios assigned by the President. The Council then adopts this list of nominee-Commissioners. The council's adoption of the commission is not an area which requires the decision to be unanimous, their acceptance is arrived at according to the rules for qualified majority voting. The European Parliament then interviews and casts its vote upon the Commissioners. The interviews of individual nominees are conducted separately, in contrast to Parliament's vote of approval which must be cast on the commission as a whole without the ability to accept or reject individual Commissioners. Once approval has been obtained from the Parliament the Commissioners can take office.[14] The current president is Ursula von der Leyen (EPP); she was elected in 2019.[13]

Elections

[edit]

Direct elections take place to the European Parliament every five years. The Council and European Council is composed of nationally elected or appointed officials and thus are accountable according to national procedures. The commission also is not directly elected although future appointments of the President must take into account of results of Parliament's elections.

Parliament's elections are held by universal suffrage of EU citizens according to national restrictions (such as age and criminal convictions). Proportional representation is used in all parliamentary constituencies.[15] Members of the European Parliament cannot also be elected nationally and are elected in national or sub-national constituencies. The first such election was in 1979, and the latest election was in 2024. The turnout was steadily falling in every EU election since 1979, until 2019, where it increased 8 pp from 42.6% to 50.7%, and then again in 2024 by 0.39 pp to 51.05%[16]

Political parties

[edit]Political parties across member states organise themselves with like-minded parties into European political parties. Most national parties are now members of a European political party. European parties behave and operate to a certain extent like national parties, receive public funding from the European Union, and put forward manifestos during the campaigns for the European elections.

European parties are horizontally present in all the main institutions – Council, Commission, Parliament – but are most active through their political groups of the European Parliament. At the beginning of every parliamentary term, European parties organise themselves, including with non-member national parties or independent candidates, to form a political group. No European party has ever held a majority in the European Parliament, however this does not have a great impact, as European parties or groups do not form a government; however, pro-European political parties usually agree among themselves to elect the President of the European Parliament.[17][18][19]

Foreign affairs

[edit]

The EU's chief diplomat, sometimes dubbed its foreign minister, is the High Representative, Kaja Kallas. The foreign policy of the European Union is characterised as being:[20]

- Multi-facet as it is carried out through different venues namely the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP)(Title V, TEU), the external dimension of internal policies and the External Action of the EU (Part Three with Titles I, III, V, VIII, XIX, XX, XXI and Part Five with Titles II, III, IV and V of the TFEU).[20]

- Multi-method as it is materialised through different venues, in practice this means that it happens in two different legal settings, the first two policy field (CFSP and CSDP) are regulated through the TEU and the second group (external dimension and external action) are addressed by the TFEU. Since the TEU represents the "intergovernmental" character of the EU and the TFEU represents the "communitary method" (supranational), in the second we see the presence of actors such as the Commission and the European Parliament playing a rather important role whereas in the intergovernmental method, the decision lies in the hands of the Council under unanimity.[20]

- Multi-level because it is embedded in the international level with different international organisations (UNO, IMF, NATO and WTO). Member States are also members of these organisations adding new actors into the game. The EU itself is a member of some of these and in practice this mean that Member States have other options to "pick from".[20]

Issues

[edit]The Financial Perspective for 2007–2013 was defined in 2005 when EU members agreed to fix the common budget to 1.045% of the European GDP.[21] UK Prime Minister Tony Blair agreed to review the British rebate, negotiated by Margaret Thatcher in 1984. Former French president Jacques Chirac declared this increase in the budget will permit Europe to "finance common policies" such as the Common Agricultural Policy or the Research and Technological Development Policy. France's demand to lower the VAT in catering was refused.[22] Controversial issues during budget debates include the British rebate, France's benefits from the Common Agricultural Policy, Germany and the Netherlands' large contributions to the EU budget, reform of the European Regional Development Funds, and the question of whether the European Parliament should continue to meet both in Brussels and Strasbourg.

The Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe (TCE), commonly referred to as the European Constitution, is an international treaty intended to create a constitution for the European Union. The constitution was rejected by France and the Netherlands, where referendums were held[23] causing other countries to postpone or halt their ratification procedures. Late in 2009, a new Reform Treaty was ratified by all member states of the European Union, and took effect on 1 December 2009.

Enlargement of the Union's membership is a major political issue, with division over how far the bloc should expand. While some see it as a major policy instrument aiding the Union's development, some fear over-stretch and dilution of the Union.[24][25]

"Counter-nationalistic shearing stress" is the term coined by one commentator for the theoretical tendency of certain regions of larger countries of the EU to wish to become fully independent members within the wider context of the European Union's "bigger umbrella". If the Union is to become "ever closer", it follows that regions with their own distinctive histories and identities within the existing member nations may see little reason to have a layer of "insulation" between themselves and the EU. The surprisingly close vote on Scottish Independence in September 2014 may be seen in this context. Others have suggested that regions of Germany could be candidates for "Euro-Balkanisation", particularly given Germany's commitment to the EU project and to a more nuanced, mature view of the notion of national allegiance.

Public trust

[edit]

91–100% 81–90% 71–80% | 61–70% 51–60% |

Public trust in the European Union in 2024 according to Eurobarometer:[27]

| Country | Tend to trust[27] in % |

Tend to not trust[27] in % |

|---|---|---|

| 46 | 46 | |

| 53 | 43 | |

| 52 | 34 | |

| 57 | 37 | |

| 40 | 53 | |

| 43 | 49 | |

| 69 | 26 | |

| 51 | 31 | |

| 62 | 22 | |

| 34 | 54 | |

| 47 | 44 | |

| 45 | 52 | |

| 53 | 41 | |

| 56 | 30 | |

| 50 | 42 | |

| 50 | 32 | |

| 68 | 20 | |

| 56 | 32 | |

| 51 | 34 | |

| 60 | 37 | |

| 52 | 36 | |

| 68 | 24 | |

| 58 | 34 | |

| 51 | 39 | |

| 39 | 55 | |

| 50 | 41 | |

| 63 | 28 |

See also

[edit]- List of European Union directives

- Euroscepticism

- Withdrawal from the European Union

- Policies of the European Union

- Anti-fascism

- Post–World War II anti-fascism

References

[edit]- ^ Miller: 1928, The Paris Peace Pact (London, G.S. Putnam's Sons) pp. 26-29

- ^ As outlined in Title I of Part I of the consolidated Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

- ^ Kleine 2009, Memo: Informal Norms in European Governance (http://www.princeton.edu/europe/events_archive/repository/05-01-2009/Kleine.pdf) p.1 Archived 18 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "EUROPA - Regulations, Directives and other acts". Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ ECB: Introduction: Euro area Archived 14 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine ecb.int

- ^ Schengen acquis and its integration into the Union Archived 27 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine europa.eu

- ^ EU Battlegroups europarl.europa.eu Archived 27 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Parliament's powers and procedures". European Parliament. Retrieved 12 June 2007.

- ^ "Decision-making in the European Union". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- ^ "Parliament – an overview. Welcome". European Parliament. Retrieved 12 June 2007.

- ^ van Grinsven, Peter (September 2003). "The European Council under Construction" (PDF). Netherlands Institution for international Relations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- ^ "Institutions: The Council of the European Union". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2007.

- ^ a b "Institutions: The European Commission". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2007.

- ^ "The European Commission". Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 18 June 2007.

- ^ The European Parliament: electoral procedures europarl.europa.eu

- ^ "Turnout | 2024 European election results | European Parliament". results.election.europa.eu/. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ European Parliament euractiv.com

- ^ Party Politics in the EU civitas.org.uk

- ^ European Parliament and Supranational party system cambridge.org Archived 14 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Keukeleire, Stephan (23 January 2014). The foreign policy of the European Union. Delreux, Tom (2nd ed.). Houndsmill, Basingstoke, Hampshire. ISBN 978-1-137-02575-3. OCLC 858311361.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Financial Perspective 2007–2013" (PDF). (236 KiB), Council of the European Union, 17 December 2005. Archived 24 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 25 January 2007.

- ^ "Poles block EU deal on lower VAT", Times Online, 31 January 2006. Accessed 24 January 2007.

- ^ "Varied reasons behind Dutch 'No'", BBC News Online, 1 June 2005. Accessed 24 January 2007.

- ^ EP Draft report on division of powers europarl.europa.eu Archived 23 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Q&A: EU Enlargement news.bbc.co.uk

- ^ "Socio-demographic trends in national public opinion". europarl.europa.eu. October 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ a b c Public opinion in the European Union: first results : report, QA6.10. Publications Office. doi:10.2775/437940. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

External links

[edit]- Official EU website: Europa

- (in French) European Elections Online

- European NAvigator: The three pillars of the European Union

- European Institute for International Law and International Relations (EIILIR) (archived)

- Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP)

- PRADO – The Council of the European Union Public Register of Authentic Travel and ID Documents Online (archived)