Polish prisoners of war in World War II

Polish prisoners of war in World War II were soldiers of the Polish Armed Forces captured by Germany and the Soviet Union during and after their invasion of Poland in 1939 (see also Soviet invasion of Poland). Following the defeat of Poland, tens of thousands of Polish soldiers were interned in camps, with many subjected to forced labor, harsh conditions, and political repression. While some prisoners were later released or escaped to join resistance movements, others suffered severe mistreatment or were executed, most notably during the Katyn massacre.

Total numbers

[edit]Polish POWs: all POWs after invasion of Poland: estimates range 650,000[1]–1,039,800[1] with the lower estimates based on number of soldiers held at POW camps and the higher, for all soldiers as well as similar groups (ex. policeman) taken into custody (many were quickly released). Out of these: 420,000[1]–694,000[2]: 28 held by Germany, and 125,000,[3] 190,000,[3] 300,000[2]: 28 or 452,500[1] held by the USSR following the Soviet invasion of Poland. Some Polish POWs in the Soviet hands were first interned in the Baltic states and fell in the Soviet hands after the Soviet occupation of the Baltics in 1940.[4]: 37 Likewise, some Polish POWs internet in Romania and Hungary were transferred to the Germans (in 1941 and 1944, respectively).[2]: 37

More Polish soldiers would be captured later in the war as Poland created several armies in exile;[2]: 37 for example, 60,000 were captured after fall of France and others, serving in the Polish Armed Forces in the West, in the Western front.[5]: 15 [2]: 37–38 15,000 Polish partisans taken into custody after the Warsaw Uprising were recognized as prisoners of war and deported to POW camps.[2]: 294

Tens of thousands of Polish POWs were "exchanged" between Germany and the USSR based on their domicile location within the relevant occupation zone (it was one of the topics discussed during the Gestapo–NKVD conferences).[2]: 35–36

In Germany

[edit]Invasion of Poland

[edit]

During the German invasion of Poland, which started World War II, hundreds of thousands of Polish soldiers became prisoners of war. During the invasion, Nazi Germany carried out a number of atrocities involving Polish prisoners of war (POWs).[2]: 28 Historians have identified over sixty instances of Polish prisoners being shot in captivity.[6]: 121 [2]: 30 The first documented massacres of Polish POWs took place as early as the first day of the war;[7] : 11 others quickly followed (ex. the Serock massacre of 5 September).[8]: 31 [9] During that period, the Wehrmacht is estimated to have mass-murdered at least 3,000 Polish POWs,[6]: 121 [10]: 241 with the largest atrocities being the Ciepielów massacre of 8 September 1939 (~300 victims[2]: 29 ) and the Zambrów massacre of 13–14 September (~200 victims).[9] Most of those atrocities are classified as war crimes of the Wehrmacht.[9]

As a prelude to The Holocaust, Polish POWs of Jewish origin were routinely selected and shot on the spot.[9][11] Those who survived were imprisoned with the other soldiers, but eventually separated from the ethnic Poles through racial screenings.[2]: 297–301 In December 1939 the German military authorities initiated the process of releasing the Jewish privates and NCOs from Stalags. When Operation Reinhard commenced, they shared the same fate as other Jews.[12] Only the fate of the Jewish officers was different. They remained in Oflags and majority of them survived the war.[13]: 236

German atrocities against Poles have been explained due to widespread historical anti-Polish sentiment among the Germans, encouraged by Nazi propaganda, which described Poles as German-hating Untermenschen. Wehrmacht communiqués warned soldiers against the alleged "fanatic" hatred of Poles towards the Germans and warned them to expect guerrilla warfare, sabotage and diversion. In particular, German officers often treated Polish soldiers of disorganized units captured behind German lines as partisans, not as regular soldiers, and felt justified in ordering their summary executions; similar treatment befell members of the Polish paramilitary formations and ad-hoc citizens watches formed before and during the campaign to aid the Polish army. This has been compounded by the lack of preparation, resources, and will to secure surrendered Polish soldiers.[9][14]: 13 [2]: 31 [15]: 65–66, 90–92 German atrocities against Polish POWs have been discussed in the context of German later and even more extreme atrocities against Soviet POWs, as setting the stage for them.[2]: 27–28, 483 [8]: 34 [16]: 179–185 They have also led a number of historians to conclude that Germany violated the Geneva convection from early days of the war.[7]: xv–xvi [17][2]: 30, 32–33 [16]: 179–185

Camps and forced labor

[edit]

Polish POWs were initially held in temporary camps; conditions in them have been described as "dreadful"; some Polish prisoners were billeted in the open as late as December.[2]: 32–33 Within months, the soldiers were moved to more permanent ones (Oflags for officers and Stalags for soldiers of lower ranks); with officers given the expected preferential treatments (relocated faster and to permanent, comparatively better conditions).[2]: 33–34, 36 The Poles were split between over twenty Stalags and eight Oflags.[2]: 33–34 Some of the major locations for Oflags hosting Polish POWs (over 20,000 officers, including 46 generals) were Oflag VI-B (Déssel, Belgium), Oflag VII-A (Murnau, Germany), Oflag II-E (Neubrandenburg, Germany), Oflag II-C (Woldenburg, Germany, now Poland), Oflag II-D (Gross Born, Germany, now Poland), and Oflag VI-G (Emslandlager Oberlangen, Oberlangen, Germany).[2]: 36 Polish soldiers captured later in the war were often grouped with Western soldiers, based on their uniforms.[2]: 37–38

Conditions of Polish POWs have been described as "much worse" than those of Western Allies.[18][8]: 34 [2]: 32–33, 36–37 Food rations were inadequate.[2]: 33–34 Religious services were held, but with no confessions allowed for security reasons.[2]: 33–34 Some prisoners died due to malnutrition and environmental conditions;[2]: 34–35 for example in January 1940 a group of 2,000 sick POWs were decreed to be released and transported from Germany to Poland; however, a tenth of them have frozen to death during the transport.[8]: 34

Many Polish POWs were used as forced laborers.[8]: 35 [2]: 10 Within several months, almost all non-officer prisoners of war (estimates range at 300,000–480,000) were stripped of their POW status and forced to work in Nazi Germany.[19][2]: 38–40 The Germans already assigned 300,000 Polish POWs for agricultural duties to help with the '39 harvest, and made arrangements for forced labor of POWS as early as January that year.[2]: 38–40 A year later, it was estimated that between 344,000 and 480,000 Polish POWs were working in the German economy.[2]: 38–40 Most of them were "civilianized" – released from POW camps, then immediately forced to sign labor contracts; this made them technically illegible for protection from the Geneva Convention. After that, the number of Polish POWs in German was reduced to 80,000 officers, NCOs, and other groups deemed unfit or unwanted in the labor force (intelligentsia, minorities including Jews, and several other categories).[2]: 38–40

A few dozen Polish officers were executed after having been recaptured during the failed escape attempt in 1943 from the Oflag VI-B.[8]: 36 [2]: 37 Others died in massacres of POWs in the Eastern Front; for example in February 1945, during the breakthrough of the Pomeranian Wall, approximately 150–200 POWs were executed by the Germans in Podgaje, an event known as the Podgaje massacre of 2 February 1945.[20]: 23 [21] Another large massacre took place following the Battle of Bautzen in April 1945, when Wehrmacht soldiers massacred the hospital column of the Polish 15th Sanitary Battalion, resulting in the deaths of around 300 POWs, including wounded soldiers and members of the medical personnel (the Horka massacre).[22]

In the Soviet Union

[edit]

As a result of the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, hundreds of thousands of Polish soldiers became prisoners of war. Official Soviet estimate for the number of POWs taken during th campaign was 190,584 and is treated as reliable by some historians.[3] Lower and higher estimates exist. Lower estimate has been given at about 125,000[3]; the higher ones range from 230,000 to as many as 450,000.[1]

Similar to what happened in the Western front against the Germans, many of the Polish POWs held by the Soviets were victims of atrocities; some during the campaign itself. The most high-profile victim of the first few weeks was General Józef Olszyna-Wilczyński, executed by the Soviets on 22 September 1939.[2]: 41 [23]: 21 [24]: 36–37 The number of Polish POWs who died in the east is estimated at at least 200–300,[23]: 21 with larger estimates in the range of 2,500[25]: 23 ; some however were killed not by the Red Army but Ukrainian or Belarusian militia and bandits.[23]: 21

Like Germans, Soviets were not prepared to deal with large number of Polish POWs, and conditions in transit camps and during transportation were very poor. The situation improved in the long term camps; 99 were established, mostly in the areas near Tarnopol, Lwów, Stanisławów, and Wołyń. Soviets also released small numbers of soldiers from the German, Ukrainian and Belarusian Polish minorities. Enlisted soldiers were used as forced labor.[2]: 42–43

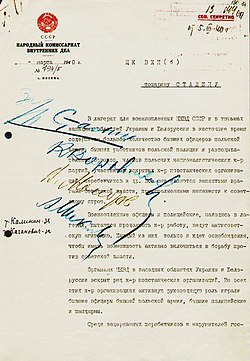

About 8,000 military officers were kept in camps in Kozelsk, Starobielsk, and Ostashkoy[2]: 44 . The conditions in the camps were poor; most religious and cultural activities were forbidden, and inmates were subject to interrogations and extensive Soviet propaganda.[2]: 44 Eventually almost all of them perished in the infamous[2]: 27 Katyn massacre (which claimed the life of over 20,000 Polish citizens; victims also included police personnel and other civilians).[2]: 45–46 [26][27][28][29] The Soviets claimed that Polish officers were released or escaped; although the massacre site was eventually uncovered by the Germans and used by the Nazi propaganda.[2]: 47–48 The Katyn massacre was subsequently covered up in communist regimes, including Poland, until the fall of communism, and was only discussed by the Western and Polish émigré historians until that time.[2]: 27 The reasons for Katyn massacre are still not fully understood by the historians, but there is a general consensus that it was done to deprive a potential future Polish military of a large portion of its talent, and to reduce future opposition to the Soviet rule, and was part of a wider plan of oppression of Polish populace in the occupied territories.[2]: 46 [25]: 23

Following the German invasion of Russia, Soviets decided to employ Polish survivors as a fighting force, which led to the creation of the Polish Armed Forces in the East.[2]: 51–53

See also

[edit]- Polish prisoners and internees in Soviet Russia and Lithuania (1919–1921)

- Prisoners of war in World War II

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Straty osobowe wojsk polskich, niemieckich i sowieckich - Polskie miesiące". polskiemiesiace.ipn.gov.pl. 20 May 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Moore, Bob (5 May 2022). Prisoners of War: Europe: 1939-1956. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198840398.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-187597-7.

- ^ a b c d Tuszynski, Marek; Denda, Dale F. (1999). "Soviet War Crimes Against Poland During the Second World War and Its Aftermath: A Review of the Factual Record and Outstanding Questions". The Polish Review. 44 (2): 183–216. ISSN 0032-2970. JSTOR 25779119.

- ^ Moore, Bob (5 May 2022). Prisoners of War: Europe: 1939-1956. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198840398.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-187597-7.

- ^ Rollings, Charles (31 August 2011). Prisoner Of War: Voices from Behind the Wire in the Second World War. Ebury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4464-9096-9.

- ^ a b Snyder, Timothy (2 October 2012). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03297-6. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ a b Datner, Szymon (1962). Crimes Committed by the Wehrmacht During the September Campaign and the Period of Military Government. Drukarnia Univ.

- ^ a b c d e f Chinnery, Philip D. (30 April 2018). Hitler's Atrocities Against Allied PoWs: War Crimes of the Third Reich. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-5267-0189-3.

- ^ a b c d e Sudoł, Tomasz (2011). "Zbrodnie Wehrmachtu na jeńcach polskich we wrześniu 1939 roku" [Wehrmacht crimes against Polish prisoners of war in September 1939] (PDF). Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej. 8–9 (129–130). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ Böhler, Jochen (2006). Auftakt zum Vernichtungskrieg: die Wehrmacht in Polen 1939 (in German). Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag. ISBN 978-3-596-16307-6. Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ Krakowski, S. (1977). "The Fate of Jewish Prisoners of War in the September 1939 Campaign" (PDF). Yad Vashem Studies. 12: 300.

- ^ Grudzińska, Marta; Rezler-Wasielewska, Violetta (2008). "Lublin, Lipowa 7. Obóz dla Żydów-polskich jeńców wojennych (1940–1943)". Kwartalnik Historii Żydów (in Polish). 4 (228): 492. ISSN 1899-3044.

- ^ Gerlach, Christian (17 March 2016). The Extermination of the European Jews. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88078-7.

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P. (2007). War of Annihilation: Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front, 1941. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-4482-6. Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ Wardzyńska, Maria (2009). Był rok 1939: operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion (in Polish). Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. ISBN 9788376290638.

- ^ a b Rossino, Alexander B. (2003). Hitler Strikes Poland: Blitzkrieg, Ideology, and Atrocity. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1234-5.

- ^ Tomiczek, Henryk (2000). "Oflag III C pamiętał o 3 Maja : przyczynek do historii oflagów" [Oflag III C remembered May 3: a contribution to the history of Oflags]. Niepodległość i Pamięć. 7 (16): 249–258.

- ^ MacKenzie, S. P. (September 1994). "The Treatment of Prisoners of War in World War II". The Journal of Modern History. 66 (3): 487–520. doi:10.1086/244883. ISSN 0022-2801.

- ^ Ulrich Herbert (16 March 1999). "The Army of Millions of the Modern Slave State: Deported, used, forgotten: Who were the forced workers of the Third Reich, and what fate awaited them?". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Piotrowski, Tadeusz (23 January 2007). Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2913-4. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ Fritz, Juergen; Anders, Edward (11 December 2012). "Mord dokonany na polskich jeńcach wojennych we wsi Podgaje (Flederborn) w lutym 1945 r." Europa Orientalis. Studia z Dziejów Europy Wschodniej i Państw Bałtyckich (in Polish) (3): 157–188. doi:10.12775/EO.2012.009. ISSN 2081-8742. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ Woszczerowicz, Zuzanna (2022). "Recenzja: Zbigniew Kopociński, Krzysztof Kopociński, Horka – łużycka Golgota służby zdrowia 2. Armii Wojska Polskiego". Zeszyty Łużyckie (in Polish). 57: 257–260. doi:10.32798/zl.954. ISSN 0867-6364.

- ^ a b c Cienciala, Anna M.; Lebedeva, Natalia S.; Materski, Wojciech (1 October 2008). Katyn: A Crime Without Punishment. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15185-5.

- ^ Sword, Keith (25 June 1991). The Soviet Takeover of the Polish Eastern Provinces, 1939–41. Springer. ISBN 978-1-349-21379-5.

- ^ a b Sanford, George (2005). Katyn and the Soviet Massacre of 1940: Truth, Justice and Memory. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-33873-8.

- ^ Fischer, Benjamin B., "The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field", Studies in Intelligence, Winter 1999-2000.

- ^ Sanford, George (2005). Katyn and the Soviet Massacre of 1940: Truth, Justice and Memory. Routledge. pp. 20–24. ISBN 978-0-415-33873-8.

- ^ Szymczak, Robert (2008). "The Vindication of Memory: The Katyn Case in the West, Poland, and Russia, 1952-2008". The Polish Review. 53 (4): 419–443. ISSN 0032-2970. JSTOR 25779772.

- ^ Fredericks, Vanessa (23 April 2011), "The Katyn Massacre and the Ethics of War: Negotiating Justice and Law", Thinking About War and Peace: Past, Present, and Future, Brill, pp. 63–71, ISBN 978-1-84888-084-9, retrieved 20 October 2024