List of ancient Iranian peoples

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

This list of ancient Iranian peoples includes the names of Indo-European peoples speaking Iranian languages or otherwise considered Iranian ethnically or linguistically in sources from the late 1st millennium BC to the early 2nd millennium AD.

Background

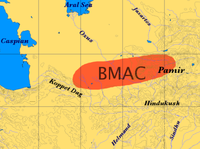

[edit]Ancient and modern Iranian peoples mostly descend from the Proto-Indo-Iranians, common ancestors respectively of the Proto-Iranians and Proto-Indo-Aryans, this people possibly was the same of the Sintashta-Petrovka culture. Proto-Iranians separated from the Proto-Indo-Aryans early in the 2nd-millennium BCE. These peoples probably called themselves by the name "Aryans", which was the basis for several ethnonyms of Iranian and Indo-Aryan peoples or for the entire group of peoples which shares kin and similar cultures.[1]

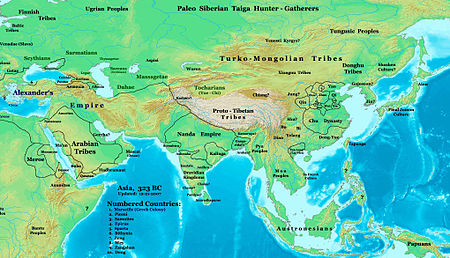

Iranian peoples first appear in Assyrian records in the 9th century BCE. In Classical Antiquity, they were found primarily in Scythia (in Central Asia, Eastern Europe, the Balkans and the Northern Caucasus) and Persia (in Western Asia). They divided into "Western" and "Eastern" branches from an early period, roughly corresponding to the territories of Persia and Scythia, respectively. By the 1st millennium BCE, Medes, Persians, Bactrians and Parthians populated the Iranian plateau, while others such as the Scythians, Sarmatians, Cimmerians and Alans populated the steppes north of the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, as far as the Great Hungarian Plain in the west. The Saka tribes remained mainly in the far-east, eventually spreading as far east as the Ordos Desert.[1]

Ancient Iranian peoples spoke languages that were the ancestors of modern Iranian languages, these languages form a sub-branch of the Indo-Iranian sub-family, which is a branch of the family of the wider Indo-European languages.[1]

Ancient Iranian peoples lived in many regions and, at about 200 BC, they had as farthest geographical points dwelt by them: to the west the Great Hungarian Plain (Alföld), east of the Danube river (where they formed an enclave of Iranian peoples), Ponto-Caspian steppe in today's southern Ukraine, Russia and far western Kazakhstan, and to the east the Altay Mountains western and northwestern foothills and slopes and also western Gansu, Ordos Desert, and western Inner Mongolia, in northwestern China(Xinjiang), to the north southern West Siberia and southern Ural Mountains (Riphean Mountains?) and to the south the northern coasts of the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea.:[1][2]: 348 The geographical area dwelt by ancient Iranian peoples was therefore vast (at the end of the 1st Millennium BC they dwelt in an area of several million square kilometers or miles thus roughly corresponding to half or slightly less than half of the geographical area that all Indo-European peoples dwelt in Eurasia).[1]

During Late Antiquity, in a process that lasted until Middle Age, the Iranian populations of Scythia and Sarmatia, in the western (Ponto-Caspian) and central (Kazakh) Eurasian Steppe and most of Central Asia (that once formed a large geographic area dwelt by Iranian peoples), started to be conquered by other non-Iranian peoples and began to be marginalized, assimilated or expelled mainly as result of the Turkic peoples conquests and migrations that resulted in the Turkification of the remaining Iranian ethnic groups in Central Asia and the western Eurasian steppe. Germanic, Slavic and later Mongolian conquests and migrations also contributed to the decline of the Iranian peoples in these regions. By the 10th century, the Eastern Iranian languages were no longer spoken in many of the territories they were once spoken, with the exception of Pashto in Central Asia, Ossetic in the Northern Caucasus and Pamiri languages in Badakhshan. Most of Central Asia and the western Eurasian steppe was almost completely Turkified. However, in most of the southern regions, corresponding to the Iranian Plateau and mountains, more densely populated, Iranian peoples continued to be most of the population and remained so until modern times.[1]

Various Persian empires flourished throughout Antiquity, however, they fell to the Islamic conquest in the 7th century, although other Persian empires formed again later.

Ancestors

[edit]

- Proto-Indo-Europeans (Proto-Indo-European speakers)

- Proto-Indo-Iranians (common ancestors of the Iranian, Nuristani and Indo-Aryan peoples) (Proto-Indo-Iranian speakers)

- Proto-Iranians (Proto-Iranian speakers)

- Proto-Indo-Iranians (common ancestors of the Iranian, Nuristani and Indo-Aryan peoples) (Proto-Indo-Iranian speakers)

Ancient Iranian Peoples

[edit]Source:[4]

- Airyas

- Ahiryas

- Dahis (possible ancestors of the Dahae or Dasa)

- Sainus

- Sairimas

- Tuiryas[5][6][7] - an ancient Iranian ethnic group, their land was called Turan, a word that later was applied to the lands north of Iran and the Iranian Plateau and mountains, i.e. all Central Asia (including Transoxiana). (in the Avesta "Turan" had the meaning of an Iranian tribe, only later the name had the meaning of lands inhabited by Turkic tribes).[8]

- Yashtians

Northeast Iranians (Northern East Iranians)

[edit]

- Saka / Sacans (Sakā) / Scytho-Sarmatians - Sarmatians and Scythians, Scythian cultures peoples of the Western (or Ponto-Caspian steppe), Central (or Kazakh steppe) Eurasian steppe and Central Asia that spoke several Scytho-Sarmatian Iranian languages and had a kin and similar culture. The name Sakā was an Old Persian generic word for all Iranian speaking peoples, Scythians, Sarmatians and others, that lived in the Eurasian Steppe and were nomad or semi nomadic pastoralists/herders)[9][10]

- Western Saka (Western Scytho-Sarmatians) (Scythians in a narrow sense - the Scythian culture peoples that lived in the Ponto-Caspian steppe, the west part of the Eurasian Steppe)

- Scythians / Scoloti (Skolotoí / Saka) (Sakā para Draya - "Sakas Beyond the Sea" - The Sea was the Pontus Euxinus / Black Sea) (the Old Persian word "Saka" covered both Scythians and Sarmatians)

- Achaei (Acae)

- Agavi Scythae

- Core Scythians

- Hamaxobii

- Lower Danube Scythians (a small tribal group of Scythians that took refuge in the areas of today's Dobrogea)

- Crimean Scythians (a small tribal group of Scythians that took refuge in the areas of today's Crimea)

- Tauri Scythae / Tauroscythae, Tauri Scythians or Scythianized Tauri, they lived in the plains of Northern Taurica or Tauris Peninsula (today called Crimea)

- Scythians / Scoloti (Skolotoí / Saka) (Sakā para Draya - "Sakas Beyond the Sea" - The Sea was the Pontus Euxinus / Black Sea) (the Old Persian word "Saka" covered both Scythians and Sarmatians)

- Eastern Saka (Eastern Scytho-Sarmatians) (Scythians in the broad sense of Scythian culture peoples) (in a narrow sense, Eastern Saka refers to the Iranian nomadic or seminomadic pastoralist peoples that lived in the central part of the Eurasian steppe or Kazakh steppe and Central Asia, they were called "Sarmatians" by the Greeks and "Saka" by the Persians) (the Old Persian word "Saka" covered both Scythians and Sarmatians)

- Central Asian Sakas / Central Asia Scytho-Sarmatians

- Core Central Asian Sakas / Core Central Asian Scytho-Sarmatians

- Amyrgians (Sakā haumavargā - Soma Drinkers/Gatherers Sakas) (Sakā para Sugudam - Sakas Beyond Sogdiana, may have been the same as the Sakā haumavargā i.e. the Amyrgians, the Greek name for the same people) (roughly in today's Ferghana Valley and basin, parts of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan)

- Anaraci

- Aspisi / Aspisii

- Cachassae

- Chauranaci

- Southwest Central Asian Sakas / Southwest Central Asian Scytho-Sarmatians

- Dahae-Amardi

- Dahae / Dahas / Dasa

- Parni / Aparni (tribe where Arsaces I became chief, later he became the first king of Parthia, he was the founder of the Arsacid Dynasty, that ruled the Parthian Empire; several ancient authors said he was of Scythian or Bactrian origin)

- Pissuri

- Xanthii

- Amardians / Mardians (initially they lived in Southwest Central Asia, however they migrated southwest towards central Alborz Mountains and plains of southern Caspian Sea coast and later they became assimilated into Northwestern Iranians subgroup of Western Iranians)

- Dahae / Dahas / Dasa

- Tapurians / Tapuri / Tapuraei (initially they lived in Southwest Central Asia, however they migrated southwest toward Tapuria, in the east Alborz Mountains and plains of the southeastern Caspian Sea coast, and later they became assimilated into Northwestern Iranians subgroup of Western Iranians) (origin of the name Tapuristan or Tabaristan, the land where they went living)

- Dahae-Amardi

- Massagetae / Orthocorybantians (Sakā tigraxaudā - Pointy Hoods / Pointed Hats Sakas or Scythians) (Massagetae and Sakā Tigraxaudā or Orthocorybantians, as they were known by the Greeks, may have been different names for the same people)

- Norossi

- Tectosaces (not to be confused with the Celtic Tectosages)

- Sakas (in a modern narrow sense the northernmost and easternmost Scytho-Sarmatians, including those who lived in the Tarim Basin, where Tocharians also dwelt)[11]

- Scytho-Siberians (in southern West Siberia and northern Kazakhstan, in the upper Irtysh, Ishim, Tobol and Ob' river courses regions)

- Abii / Gabii

- Altay-Sayan Sakas / Altay-Sayan Scythians / Altay-Sayan Scytho-Sarmatians (they were part of the Scythian cultures ethnic and linguistic continuum; they lived in the Altay and western slopes of the Sayan Mountains and possibly they were the people that formed the Pazyryk culture) (possibly they conquered or expelled the older Afanasievo culture people, which were possibly descendant from the Proto-Tocharians)[1] (there is the strong possibility that Proto-Turkics were influenced by the Altay-Sayan Sakas and vice versa and also to a possibility of an ethnic mixing in this region between larger West Eurasian and East Eurasian populations)

- Galactophagi ("Milk Drinkers" / "Milk Eaters") (real or legendary people)

- Galactopotae (real or legendary people)

- Hippemolgi ("Mare-Milkers") (real or legendary people)

- Hippophagi ("Horse Eaters") (real or legendary people)

- Thyssagetae

- Sacaralae (Eastern Central Asia Saka) (roughly in today's central and eastern Kazakhstan) - they lived in the Chu and Sarysu river basins and their desert areas, and in the Ili river and Lake Balkash basin and most part of the Tian Shan mountains northern slope (also known as Tengri Tagh or Tengir-Too mountains).

- Tarim Basin Sakas (mainly in the western and southern regions)

- Gumo Sakas / Tumshuq Sakas (they lived in today's Tumshuq region and city) (they spoke Tumshuqese or Tumshuqese Saka, a Northeast Iranian language or dialect)

- Kashgar Sakas (they lived in Kashgar city and region)

- Khotan Sakas (they lived in the Khotan region, known as Gaustana in Sanskrit and Prakrit texts) (they spoke Khotanese or Khotanese Saka, a Northeast Iranian language or dialect)

- Indo-Scythians / Indo-Sakas (a group of Sakas that migrated towards East Iranian Plateau, Indus valley and India)

- Scytho-Siberians (in southern West Siberia and northern Kazakhstan, in the upper Irtysh, Ishim, Tobol and Ob' river courses regions)

- Core Central Asian Sakas / Core Central Asian Scytho-Sarmatians

- Sarmatians Proper / Sauromatae

- Aorsi-Alans (two closely related Sarmatian tribes or the same tribe known by different names)

- Aorsi (they lived northeast of the Siraces) (Yancai or Yentsai was the Chinese name of a State that could be identical with an Aorsi one)

- Lower Aorsi (Western Aorsi)

- Upper Aorsi (Eastern Aorsi) (from northern Caspian Sea coast to the northern Aral Sea coast) (identical with the Alans?)

- Alans (a closely related people or tribe with the Aorsi Sarmatians or the same people known by two different names) (Aryan > *Alyan > Alan)[12][13][14] (Ossetians / Irættæ are a modern branch) (also called "Melanchlaeni" - "Black-Cloaks", not to be confused with other two peoples called by that same name that were: the "Melanchlaeni" - "Black-Cloaks" of Pontus, and the "Melanchlaeni" - "Black-Cloaks" of the far north)

- Iasi[15][16] (Iasi / Jassi / Jasz are descendants from a group of Alans that migrated westward, they are related but not identical to the oldest Iazyges)

- Roxolani (an offshoot and eastern branch of the Alans)

- Banat Roxolani (a branch of the Roxolani that migrated westward)

- Agaragantes / Arcaragantes (Free Sarmatians)[17]

- Aorsi (they lived northeast of the Siraces) (Yancai or Yentsai was the Chinese name of a State that could be identical with an Aorsi one)

- Cissianti

- Iazyges / Iazyges Metanastae / Iaxamatae

- Khorouathoi / Choruathi / Haravati (their name may have influenced the ethnonym of the Croats but are not necessarily their ancestors or of most of them)

- Phoristae

- Rhymnici, they dwelt along Rha river banks (today's Volga) in the steppe area (the adjective seems to derive from the name "Rha" or "Rā", the Scythian name for the Volga river) (Oares was the Greek name for this river)

- Rimphaces

- Serboi (their name may have influenced the ethnonym of the Serbs)

- Siraci / Siraces

- Spondolici

- Urgi[18]

- Aorsi-Alans (two closely related Sarmatian tribes or the same tribe known by different names)

- Central Asian Sakas / Central Asia Scytho-Sarmatians

- Khwarezmians-Sogdians

- Chorasmians / Khwarezmians

- Sogdians - the people that lived in Sogdiana, possible ancestors of the Yaghnobis (Kangju – Chinese name of a State probably identical to the Sogdians[19])

- Western Saka (Western Scytho-Sarmatians) (Scythians in a narrow sense - the Scythian culture peoples that lived in the Ponto-Caspian steppe, the west part of the Eurasian Steppe)

Southeast Iranians (Southern East Iranians)

[edit]

- Arachosians / Arachoti

- Arians Proper / Arii

- Ariaspae / Evergetae

- Bactrians

- Drangians / Drangae / Zarangians / Zarangae

- Gedrosians / Gedrosii / Gedroseni

- Aparytae

- Arabitae / Arbies

- Iranian Ichthyophagi / Iranian Ichthyophagoi (Iranian Fish-Eaters)

- Oritae

- Paricanians / Paricanii / Oreitae / Orae (from Old Persian Barikânu - Mountain people)

- Rhamnae

- Margians

- Mycae

Northwest Iranians (Northern West Iranians)

[edit]- Aenianes

- Astabeni

- Carduchi / Corduchi[23] / Cyrtaei / Cyrtii (mentioned by Strabo, and possible ancestors of the Kurds according to Muhammad Dandamayev) (See "Carduchi" in Encyclopædia Iranica)

- Derbiccans / Derbiccae / Derbices (oldest inhabitants of the land later known as Tapuristan or Tabaristan and part of Hyrcania before the arrival of the Tapures or Tapuri)

- Dribyces

- Gelae / Gilites (possible ancestors of the Gilaks), although associate they were not the same people as the Cadusii

- Azaris (inhabited Iranian Azerbaijan, possible ancestors of the Tats and Talysh)

- Hyrcani, they lived in Hyrcania

- Medes

- Arizanti

- Budii

- Busae

- Magi (Median tribe from where, over time, many of the Zoroastrian priests came, it was a priestly tribe for the Zoroastrian religion, somehow similar to the role Levites, from the Tribe of Levi, had in Judaism, the religion of the ancient Hebrews, Jews or Israelites)

- Paraetaceni / Paraetacae / Paraetaci

- Sidices

- Struchates

- Vaddasi

- Parthians

- Nisaei (in the region of Nisa, first capital of the Parthians, Parthia)

- Seven Parthian clans (Seven Great Houses of Iran) (tribe of seven clans) - Ispahbudhan / Aspahbadh (seat was in Gurgan), Karen / Karen-Pahlavi (Kārēn-Pahlaw) (seat was in Nahavand), Mihran / Mehrān (seat was in Ray), Spandiyadh / Spendiad / Isfandiyar (seat was in Ray), Suren (seat was in Sakastan or Sistan, ancient Zaranka, Zranka or Drangiana), Varaz (seat was in Eastern Khorasan), Zik (seat was in Adurbadagan or Aturpatakan, called Atropatene by the Greeks, today's modern Iranian Azerbaijan) ("House" was synonym of "Clan")

- Indo-Parthians / Suren Parthians (origin in the Suren Parthians)

- Vitii

Southwest Iranians (Southern West Iranians)

[edit]- Carmanians / Garmanians (Carmani / Garmani) / Germani / Germanii (a variant of Carmani, i.e. Carmanians, not to be confused with the Germanic peoples of Europe, that were also Indo-European peoples but from another branch or subfamily)

- Proto-Persians (Parsua / Parsumash)[24]

- Persians

- Dai

- Derusiaei

- Dropici

- Maraphii (one of the three main and leading ancient Persian tribes)[25]

- Mardi / Southern Mardi

- Maspii (one of the three main and leading ancient Persian tribes)[26]

- Panthialaei

- Pasargadae (one of the three main and leading ancient Persian tribes, this was the tribe that contained the clan of the Achaemenids, House of Achaemenes, from which Cyrus the Great, founder of the Persian Empire, was a member)[27] ("House" was synonym of "Clan") (Pasargadae, the first capital of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, was in the land of this tribe and took its name from them)[28]

- Pateischoreis

- Rhapses

- Sagartians / Asagartians (their exact location is unknown; according to Herodotus (1.125, 7.85) they were related to the Ancient Persians, which dwelt in southwestern Iran and spoke a southwestern Iranian language) (there is the possibility, by phonetic change, that their name survives in the name of the Zagros Mountains if they were identical to the Zikirti; there is also the possibility that they dwelt in northeastern Iran, south of the Parthians, and not in the Zagros mountains)

- Sassanians (tribe that contained the clan of the House of Sasan, that gave the name to the tribe, from which Ardashir I, founder of the Sassanian Empire, was a member) ("House" was synonym of "Clan")

- Soxotae

- Stabaei

- Suzaei

- Persians

- Utians

Ancient peoples of uncertain origin with possible Iranian background or partially Iranian

[edit]Mainly Iranian Background

[edit]- Iranian Huns (Xwn / Xyon / Hunas) (mostly Iranian descendants from the nomadic Sakas, although many in the ruling class may have been Xunyu or Xiongnu in origin and related to the Huns or Western Huns that invaded many parts of the Western Eurasian steppe and Late Antiquity Europe)[29][30][31][32]

- Nezak Huns

- Red Huns / Kermichiones (Red = Southern)

- White Huns (Spet Xyon / Sveta Huna) (White = Western)

- Xionites / Chionites / Chionitae[34][35][36]

Iranians mixed with other non-Iranian peoples

[edit]Dacian-Iranian

[edit]- Agathyrsi

- Tyragetae[37] (may have been a mixed Daco-Getae - Iranian people, or just a Dacian-Getae people or tribe and not an Iranian one)

Greek-Iranian

[edit]Northwest Caucasian-Iranian

[edit]- Maeotians, a group of peoples that dwelt in the Maeotian Lake (Azov Sea) and Palus Maeotis (Don river delta swamps) that may have been Cimmerians, Iranian people (Scythians), West Caucasian people (Circassians / Adyghe) with an Iranian overlordship or a mixture of Iranian and West Caucasian peoples

Slavic-Iranian

[edit]- Antes, may have been a Slavic people and not an Iranian one or a mixed Iranian and Slavic people.

Slavic-Iranian or Thracian-Iranian

[edit]- Aroteres,[38][39] a Proto-Slavic or Thracian tribe with an Iranian ruling class living in the forest-steppes from the Dnieper to Vinitsa.

Thracian-Iranian

[edit]- Cimmerians,[40] they could have been a people of Thracian-Dacian origin with an Iranian overlordship, a mixture of Thracians and Iranians or a missing link between Indo-Iranian peoples and Thracians and Dacians.

- Alazones,[41] a semi-nomadic Scythian-Thracian tribe living between the Ingul and Dniester rivers.

- Callipidae,[39] a hellenized Scythian-Thracian tribe living from the Dniester estuary to the Southern Bug.

- Georgoi,[39] Scythian-Thracian tribe living in the country of Gilea around the lower Dnieper and led a sedentary lifestyle.

Mixed peoples that had some Iranian component

[edit]Celtic-Germanic-Iranian

[edit]- Bastarnae, an ancient people who between 200 BC and 300 AD inhabited the region between the Carpathian Mountains and the river Dnieper, to the north and east of ancient Dacia - one possible origin of the name is from Avestan and Old Persian cognate bast- "bound, tied; slave" (cf. Ossetic bættən "bind", bast "bound"), and Proto-Iranian *arna - "offspring"

- Atmoni / Atmoli

- Peucini / Peucini Bastarnae (a branch of the Bastarnae that lived in the region north of the Danube Delta)

- Sidoni / Sidones

Possible Iranian or Non-Iranian peoples

[edit]Iranian or other Indo-European peoples

[edit]Iranian or Anatolian (Indo-European)

[edit]- Cappadocians or Leucosyri (White Syrians) (a possible Anatolian Indo-European people and not an Iranian one)

Iranian or Germanic

[edit]Iranian or Indo-Aryan

[edit]- Dadicae / Daradai / Daradas (Darada > Darda > Dard?) (may have been possible ancestors of the Dards, an Indo-Aryan people, and not an Iranian one), they dwelt in the region of the upper course of the Indus, in modern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Gilgit area of the modern Gilgit-Baltistan, both in Pakistan and also in Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh in India.

- Sattagydans, people that dwelt in Sattagydia (Old Persian Thataguš; th = θ, from θata - "hundred" and guš - "cows", country of the People of "Hundred Cows"), may have been an Iranian people of Sindh with Indo-Aryan influence or the opposite, an Indo-Aryan people of Sindh with Iranian influence.

- Sogdi (Sogdoí), people that inhabited where today is the Sibi Division valley in Balochistan, between Balochistan and Sindh, and most of the Larkana Division, and parts of the Sukkur Division to the west of the Indus river, in Sindh, their main city was called Sogdorum Regia (maybe today's Sukkur) by the ancient Greek and Roman authors, and was on the Indus river banks. They may have been, as the name could tell, a branch of the Sogdians, the "Indus Sogdians", in a region of the west Indus valley or they also may have been an Indo-Aryan people of the Indus valley with a coincidental name with the Sogdians.

- Shakya - a clan of Iron Age India (1st millennium BCE), habitating an area in Greater Magadha, on the foothills of the Himalaya mountains. Some scholars argue that the Shakya were of Scythian (Saka) origin and assimilated into Indo-Aryan peoples.[42][43] Siddhartha Gautama (also known as Buddha or Shakyamuni - Sage of the Shakyas) (c. 6th to 4th centuries BCE), whose teachings became the foundation of Buddhism, was the best-known Shakya.

Iranian or Nuristani

[edit]- Kambojas / Komedes / Kapisi / Rishikas / Tambyzoi / Ambautae[44][45] - a people that lived in a country called Kumuda, probably in what is now part of Afghanistan. There are different views among scholars about their ethnic and linguistic kinship. According to some they are possible ancestors of Pamir peoples in the Pamir Mountains, roughly Badakhshan region of Tajikistan and Afghanistan and parts of the Hindu Kush or Paropamisus in east central Afghanistan and northwestern Pakistan)[46][47][48] According to other scholars[49][50][51] they were an old transitional people between Iranian and Indo-Aryan peoples and as such they may have been the ancestors of the Nuristani people (until the end of the 19th century they were known as Kafirs because they were not Muslims, and practiced an ancient Indo-Iranian religion like today the Kalash people). In Antiquity, one of the regions that they dwelt was in the southern and eastern slopes of the Paropamisus Mountains (today's Hindu Kush in east central Afghanistan and northwestern Pakistan)

- Ambautae

- Ashvakas / Assacenii / Assacani / Aspasii (Aspasians): A few scholars have linked the historical Afghans (modern Pakhtuns/Pashtuns) to the Ashvakas (the Ashvakayanas and Ashvayanas of Pāṇini or the Assakenoi and Aspasio of Arrian). The name Afghan is said to have derived from the Ashvakan of Sanskrit texts.[52][53][54] Ashvakas are identified as a branch of the Kambojas. This people was known, by Greek and Roman authors, as Assakanoi and Assacani. The similarity of the name Assacani with the name Sacae/Sacans/Sakas made that the two peoples were confused by Greeks and Romans (as is shown in map 11 regarding the Pamir mountains on the upper right edge). However the Pamir mountains were dwelt by the Asvaka Kambojas and not by the Sacans although they were related peoples (they were both East Iranians, however the Asvaka Kambojas were or Southeast Iranians or ancestors of the Nuristani while the Sacans/Sakas, Scythians or Sarmatians, were Northeast Iranians).

- Cabolitae, in the region of Kabul (today's capital of Afghanistan), part of the old Kingdom of Kapisa

- Indo-Kambojas

- Western Kambojas (spread and scattered in Sindhu, Saurashtra, Malwa, Rajasthan, Punjab and Surasena)

- Eastern Kambojas (some formed the Kamboja-Pala Dynasty of Bengal)

- Parama Kambojas, Kumuda or Komedes, of the Alay Valley or Alay Mountains, north of Hindukush / Paropamisus in today's far southern Kyrgyzstan and far northern Tajikistan. They formed the Parama Kamboja Kingdom. In ancient Sanskrit texts, their territory was known as Kumudadvipa and it formed the southern tip of the Sakadvipa or Scythia. In classical literature, this people are known as Komedes. Indian epic Mahabharata designates them as Parama Kambojas[55]

- Rishikas, some historians believe the Rishikas were a part of, or synonymous with, the Kambojas. However, there are other theories regarding their origins.

- Tambyzi / Tambyzoi

Iranian or Slavs

[edit]- Limigantes[56] (may have been a non-Sarmatian subject people - slaves or serfs of the Sarmatians, some scholars think they were Slavs)[57]

Iranian or Thracian

[edit]- Tauri, they lived in the mountains of Southern Taurica or Tauris Peninsula (today's Crimea); non scythianized Tauri.

Iranian or Tocharian

[edit]There are different or conflicting views among scholars regarding the ethnic and linguistic kinship of the peoples known by the Han Chinese as Wusun and Yuezhi and also other less known peoples (a minority of scholars argue that they were Tocharians, based, among other things, on the similarity of names like "Kushan" and the native name of "Kucha" (Kuśi) and the native name "Kuśi" and Chinese name "Gushi" or the name "Arsi" and "Asii",[58] however most scholars argue that they were possibly Northeastern Iranian peoples)[59][60]

- Argippaei

- Asii / Issedones / Wusun (may have been the same people called by different exonym names)

- Asii / Asioi / Osii, an ancient Indo-European people of Central Asia, during the 2nd and 1st Centuries BCE, known only from Classical Greek and Roman sources.

- Issedones, people that lived north and northeast of the Sarmatians and Scythians in Western Siberia or Chinese Turkestan (Xinjiang) (may have been the same people as the Asii or Asioi).

- Wusun[61] - some speculate that they were the same as the Issedones / Essedones

- Gushi or Jushi or Gushineans (an obscure ancient people that lived in two regions: in the Turpan Basin, i.e. Chinese Jushi or Gushi, including Khocho or Qočo, known in Chinese as Gaochang; and also in a large northern region, roughly in many parts of the region later known as Dzungaria, south of the Altay Mountains; they were the basis of the Gushi or Jushi Kingdom. They spoke a language that eventually diverged into two dialects, as noted by diplomats from the Han empire) (they may have been one of the peoples misnamed "Tocharians", speakers of Tocharian A?) (there are different views among scholars about their ethnic and linguistic kinship)

- Nearer Gushi / Anterior Gushi, in the Turpan Basin

- Further Gushi / Posterior Gushi, the region north of the Turpan Basin, 10 km north of Jimasa, 200 km north of Jiaohe, roughly in Dzungaria.[62]

- Yuezhi / Gara?[63][64][65] (an ancient Indo-European speaking people, in the western areas of the modern Chinese province of Gansu, during the 1st millennium BC, or in Dunhong, in the Tian Shan, later they migrated westward and southward into south Central Asia, in contact and conflict with the Sogdians and Bactrians, and they possibly were the people called by the name Tocharians or Tukhara, which was possibly an Iranian speaking people not to be confused with another people misnamed or not as "Tocharians") (according to the Iranian historian Jahanshah Derakhshani the Kochi or Kuchi people, a group of nomadic Ghilji or Ghilzai Pakhtun, are descendants from the Yuezhi that were assimilated into the Pakhtun, the name derives from Guci, formerly Chinese: 月氏; pinyin: Yuèzhī)

- Greater-Yuezhi (Tu Gara?) (Dà Yuèzhī – 大月氏) (Tu Gara > Tu Kara? > Tu Khara?) Possibly the Iranian Tocharians (not to be confused with the peoples called "Tocharians" in a misnomer) (possibly they were the ancestors of the Kushans)

- Tusharas (Tukharas?), could have been identical with the Greater-Yuezhi, the greater part of Yuezhi, are the people that migrated from western Gansu and after from the Ili Valley, migrated southward and settled in Tukhara, another name for Bactria after the invasion of the Iranian Tocharians that came from the north and northeast (not to be confused with the peoples mistakenly called "Tocharians" which were of another Indo-European branch of peoples)

- Kushans (Chinese: 貴霜; pinyin: Guìshuāng), they were the basis of the Kushan Empire)

- Tusharas (Tukharas?), could have been identical with the Greater-Yuezhi, the greater part of Yuezhi, are the people that migrated from western Gansu and after from the Ili Valley, migrated southward and settled in Tukhara, another name for Bactria after the invasion of the Iranian Tocharians that came from the north and northeast (not to be confused with the peoples mistakenly called "Tocharians" which were of another Indo-European branch of peoples)

- Lesser-Yuezhi (Xiǎo Yuèzhī – 小月氏)

- Greater-Yuezhi (Tu Gara?) (Dà Yuèzhī – 大月氏) (Tu Gara > Tu Kara? > Tu Khara?) Possibly the Iranian Tocharians (not to be confused with the peoples called "Tocharians" in a misnomer) (possibly they were the ancestors of the Kushans)

Iranian, Tocharian or Turkic

[edit]- Ordos culture people (in the Upper or North Ordos Plateau or the Ordos Desert) (if ancient Indo-European, they would have been the easternmost people)[66][67][68][69] (they may have been a people closely related to the Yuezhi)

Iranian or Non-Indo-European peoples

[edit]Iranian or Northeast Caucasian

[edit]- Cadusii,[70] warlike people living just north of Medes with possible Iranian or Caucasian origin.

- Caspians,[71] were a people of antiquity who dwelt along the southern and southwestern shores of the Caspian Sea, in the region known as Caspiane.

Iranian or Turkic

[edit]- Xiongnu (ruling class)[72] The Xiongnu could also be synonymous with the Huns, that are assumed to be a Turkic people, although there is not certainty or consensus about this matter.

Iranian or Ugric

[edit]- Iyrcae / Iyrkai, people that lived northeast of the Thyssagetae, they dwelt in far southwestern Siberia, in the upper basins of the Tobol and the Irtysh rivers, possibly they are the ancestors of the Ugrian peoples, Khanty and Mansi and the more distantly related Magyars (Hungarians), they are speakers of Uralic languages and not Iranian. These peoples were collectively called Yugra, where the adjective "Ugric" comes from (possible phonetic change: *Iurka > *Iukra > *Iugra > Jugra or Yugra; J = English Y; u or ü, Ancient Greek y = ü). They were culturally influenced by ancient Iranian peoples (including language borrowings). The name "Iyrcae" sometimes was wrongly spelt as "Tyrcae" "(Türkai)" by ancient authors (like Pliny the Elder and Pomponius Mela) but there is no connection to the Turkic peoples (Turks).

Semi-legendary peoples (inspired by real Iranian peoples)

[edit]- Amazons, a semi-legendary people or tribe of women warriors (an all-female tribe) that Greek authors such as Herodotus and Strabo said to be related to the Scythians and the Sarmatians, however, there could be some historical background for a real people with Iranian etymology (*ha-mazan- "warriors") that lived in Scythia and Sarmatia, but later became the subject of wild exaggerations and myths. Ancient authors said that they guaranteed their continuity through reproduction with the Gargareans (an all-male tribe).

- Gargareans, a semi-legendary people or tribe only formed by men (an all-male tribe), however, there could be some historical background for a real people, but later became the subject of wild exaggerations and myths. Ancient authors said that they guaranteed their continuity through reproduction with the Amazons (an all-female tribe).

- Arimaspae / Arimaspi / Arimphaei / Riphaeans, they lived north of the Scythians in the southeast foothills of the Riphean Mountains (Ural Mountains?), although a semi-legendary people or tribe there could be some historical background for a real people with Iranian etymology (Ariama: love, and Aspa: horses) that lived in that region but they were later turned as base for a myth, especially for the one-eyed beings that fought with the griffins.

See also

[edit]- Iranian peoples

- Iranian languages

- List of ancient Indo-Aryan peoples and tribes

- List of Rigvedic tribes

- List of ancient Greek tribes

- List of ancient Germanic peoples and tribes

- List of ancient Slavic peoples and tribes

- List of ancient Celtic peoples and tribes

- List of ancient Italic peoples

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Mallory, J.P.; Douglas Q. Adams (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- ^ Harmatta, János (1992). "The Emergence of the Indo-Iranians: The Indo-Iranian Languages" (PDF). In Dani, A. H.; Masson, V. M. (eds.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Dawn of Civilization: Earliest Times to 700 B. C. UNESCO. pp. 346–370. ISBN 978-92-3-102719-2. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

From the first millennium b.c., we have abundant historical, archaeological and linguistic sources for the location of the territory inhabited by the Iranian peoples. In this period the territory of the northern Iranians, they being equestrian nomads, extended over the whole zone of the steppes and the wooded steppes and even the semi-deserts from the Great Hungarian Plain to the Ordos region in northern China.

- ^ Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05887-0

- ^ Gnoli, Gherardo (1980). Zoroaster's Time and Homeland. Naples: Instituto Univ. Orientale. OCLC 07307436. Iranian tribes that also keep on recurring in the Yasht, Airyas, Tuiryas, Sairimas, Sainus and Dahis

- ^ Allworth, Edward A. (1994). Central Asia: A Historical Overview. Duke University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-8223-1521-6.

- ^ Diakonoff, I. M. (1999). The Paths of History. Cambridge University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-521-64348-1. Turan was one of the nomadic Iranian tribes mentioned in the Avesta. However, in Firdousi's poem, and in the later Iranian tradition generally, the term Turan is perceived as denoting 'lands inhabited by Turkic speaking tribes.

- ^ Gnoli, Gherardo (1980). Zoroaster's Time and Homeland. Naples: Instituto Univ. Orientale. OCLC 07307436. Iranian tribes that also keep on recurring in the Yasht, Airyas, Tuiryas, Sairimas, Sainus and Dahis

- ^ Diakonoff, I. M. (1999). The Paths of History. Cambridge University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-521-64348-1. Turan was one of the nomadic Iranian tribes mentioned in the Avesta. However, in Firdousi's poem, and in the later Iranian tradition generally, the term Turan is perceived as denoting 'lands inhabited by Turkic speaking tribes.

- ^ Simpson, St John (2017). "The Scythians. Discovering the Nomad-Warriors of Siberia". Current World Archaeology. 84: 16–21. "nomadic people made up of many different tribes thrived across a vast region that stretched from the borders of northern China and Mongolia, through southern Siberia and northern Kazakhstan, as far as the northern reaches of the Black Sea. Collectively they were known by their Greek name: the Scythians. They spoke Iranian languages..."

- ^ Royal Museums of Art and History (2000). Ancient Nomads of the Altai Mountains: Belgian-Russian Multidisciplinary Archaeological Research on the Scytho-Siberian Culture. "The Achaemenids called the Scythians " Saka " which sometimes leads to confusion in the literature. The term " Scythians " is particularly used for the representatives of this culture who lived in the European part of the steppe zone. Those who lived in Central Asia are often called Sauromates or Saka and in the Altai area, they are generally known as Scytho-Siberians."

- ^ Dandamayev 1994, p. 37 "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Central Asia and Eastern Turkestan to distinguish them from the related Massagetae of the Aral region and the Scythians of the Pontic steppes. These tribes spoke Iranian languages, and their chief occupation was nomadic pastoralism."

- ^ Golden 2009.

- ^ Abaev & Bailey 1985, pp. 801–803.

- ^ Alemany 2000, p. 3.

- ^ Mayer, Antun (April 1935). "Iasi". Journal of the Zagreb Archaeological Museum. 16 (1). Zagreb, Croatia: Archaeological Museum. ISSN 0350-7165.

- ^ Schejbal, Berislav (2004). "Municipium Iasorum (Aquae Balissae)". Situla - Dissertationes Musei Nationalis Sloveniae. 2. Ljubljana, Slovenia: National Museum of Slovenia: 99–129. ISSN 0583-4554.

- ^ Ammianus XVII.13.1

- ^ Minns, Ellis Hovell (2011-01-13). Scythians and Greeks: A Survey of Ancient History and Archaeology on the North Coast of the Euxine from the Danube to the Caucasus. ISBN 9781108024877.

- ^ Sinor, Denis (1 March 1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 153. ISBN 0-521-24304-1. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

... the K'ang-chii who were perhaps the Sogdians of Iranian stock...

- ^ Macdonell, A.A. and Keith, A.B. 1912. The Vedic Index of Names and Subjects.

- ^ Map of the Median Empire, showing Pactyans territory in what is now Afghanistan and Pakistan...Link

- ^ "The History of Herodotus Chapter 7, Written 440 B.C.E, Translated by George Rawlinson". Piney.com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2012-09-21.

- ^ "Introduction to Old Iranian". Archived from the original on 2018-09-24. Retrieved 2006-11-18.

- ^ "Persis | ancient region, Iran".

- ^ "Persis | ancient region, Iran".

- ^ "Persis | ancient region, Iran".

- ^ "Persis | ancient region, Iran". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-08-07.

- ^ "Persis | ancient region, Iran".

- ^ "GÖBL, ROBERT". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2017-08-10.

- ^ Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective, Robert L. Canfield, Cambridge University Press, 2002 p.49

- ^ Macartney, C. A. (1944). "On the Greek Sources for the History of the Turks in the Sixth Century". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. School of Oriental and African Studies. 11 (2): 266–75. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00072451. ISSN 1474-0699. JSTOR 609313. "the name "Chyon", originally that of an unrelated people, was "transferred later to the Huns owing to the similarity of sound".

- ^ Richard Nelson Frye, "Pre-Islamic and early Islamic cultures in Central Asia" in "Turko-Persia in historical perspective", edited by Robert L. Canfield, Cambridge University Press, 1991. pg 49. "Just as later nomadic empires were confederations of many peoples, we may tentatively propose that the ruling groups of these invaders were, or at least included, Turkic-speaking tribesmen from the east and north, although most probably the bulk of the people in the confederation of Chionites... spoke an Iranian language.... This was the last time in the history of Central Asia that Iranian-speaking nomads played any role; hereafter all nomads would speak Turkic languages".

- ^ Sinor, Denis (1 March 1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 300. ISBN 0-521-24304-1. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

There is no consensus concerning the Hephthalite language, though most scholars seem to think that it was Iranian.

- ^ Felix, Wolfgang. "CHIONITES". Encyclopædia Iranica. Bibliotheca Persica Press. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

CHIONITES... a tribe of probable Iranian origin that was prominent in Bactria and Transoxania in late antiquity.

- ^ Macartney, C. A. (1944). "On the Greek Sources for the History of the Turks in the Sixth Century". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. School of Oriental and African Studies. 11 (2): 266–75. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00072451. ISSN 1474-0699. JSTOR 609313. "the name "Chyon", originally that of an unrelated people, was "transferred later to the Huns owing to the similarity of sound".

- ^ Richard Nelson Frye, "Pre-Islamic and early Islamic cultures in Central Asia" in "Turko-Persia in historical perspective", edited by Robert L. Canfield, Cambridge University Press, 1991. pg 49. "Just as later nomadic empires were confederations of many peoples, we may tentatively propose that the ruling groups of these invaders were, or at least included, Turkic-speaking tribesmen from the east and north, although most probably the bulk of the people in the confederation of Chionites... spoke an Iranian language.... This was the last time in the history of Central Asia that Iranian-speaking nomads played any role; hereafter all nomads would speak Turkic languages".

- ^ Prichard Cowles, James (1841). "Ethnography of Europe. 3d ed. p433.1841". 17 January 2015. Houlston & Stoneman, 1841. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ Melyukova, A. I. (1990). "The Scythians and Sarmatians". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 97–117. ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9.

- ^ a b c Sulimirski 1985, p. 150-174.

- ^ "Cimmerian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

The origin of the Cimmerians is obscure. Linguistically they are usually regarded as Thracian or as Iranian, or at least to have had an Iranian ruling class.

- ^ Sulimirski, T. (1985). "The Scyths". In Gershevitch, I. (ed.). The Median and Achaemenian Periods. The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 2. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 149–199. ISBN 978-1-139-05493-5.

- ^ Jayarava Attwood, Possible Iranian Origins for the Śākyas and Aspects of Buddhism. Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies 2012 (3): 47-69

- ^ Christopher I. Beckwith, "Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia", 2016, pp 1-21

- ^ See also: Indian Antiquaries, 52, part 2, 1923; Indian Antiquaries, 203, 1923, p 54.

- ^ Prācīna Kamboja, Jana aura Janapada Ancient Kamboja, people and country, 1981, pp 44, Dr Jiyālāla Kāmboja, Dr Satyavrat Śāstrī; cf also: Dr J. W. McCrindle, Ptolemy, p 268.

- ^ Scholars like V. S. Aggarwala etc locate the Kamboja country in Pamirs and Badakshan (Ref: A Grammatical Dictionary of Sanskrit (Vedic): 700 Complete Reviews.., 1953, p 48, Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala, Surya Kanta, Jacob Wackernagel, Arthur Anthony Macdonell, Peggy Melcher – India; India as Known to Pāṇini: A Study of the Cultural Material in the Ashṭādhyāyī, 1963, p 38, Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala – India; The North-west India of the Second Century B.C., 1974, p 40, Mehta Vasishtha Dev Mohan – Greeks in India; The Greco-Shunga period of Indian history, or, the North-West India of the second century B.C, 1973, p 40, India) and the Parama Kamboja further north, in the Trans-Pamirian territories (See: The Deeds of Harsha: Being a Cultural Study of Bāṇa's Harshacharita, 1969, p 199, Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala).

- ^ Dr Michael Witzel also extends Kamboja including Kapisa/Kabul valleys to Arachosia/Kandahar (See: Persica-9, p 92, fn 81. Michael Witzel).

- ^ Cf: "Zoroastrian religion had probably originated in Kamboja-land (Bacteria-Badakshan)....and the Kambojas spoke Avestan language" (Ref: Bharatiya Itihaas Ki Rup Rekha, p 229-231, Jaychandra Vidyalankar; Bhartrya Itihaas ki Mimansa, p 229-301, J. C. Vidyalankar; Ancient Kamboja, People and the Country, 1981, p 217, 221, J. L. Kamboj)

- ^ The Greeks in Bactria and India 1966 p 170, 461, Dr William Woodthorpe Tarn.

- ^ The Indian Historical Quarterly, 1963, p 291; Indian historical quarterly, Vol XXV-3, 1949, pp 190-92.

- ^ Prācīna Kamboja, Jana aura Janapada Ancient Kamboja, people and country, 1981, p 44, 147, 155, Dr Jiyālāla Kāmboja, Dr Satyavrat Śāstrī.

- ^ "The name Afghan has evidently been derived from Asvakan, the Assakenoi of Arrian..." (Megasthenes and Arrian, p 180. See also: Alexander's Invasion of India, p 38; J. W. McCrindle)

- ^ "Even the name Afghan is Aryan being derived from Asvakayana, an important clan of the Asvakas or horsemen who must have derived this title from their handling of celebrated breeds of horses" (See: Imprints of Indian Thought and Culture abroad, p 124, Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan)

- ^ "Afghans are Assakani of the Greeks; this word being the Sanskrit Ashvaka meaning 'horsemen" (Ref: Sva, 1915, p 113, Christopher Molesworth Birdwood)

- ^ Mahabharata 2.27.25.

- ^ Ammianus XVII.13.1

- ^ Vernadsky 1959, p. 24.

- ^ Žhivko Voynikov (Bulgaria). SOME ANCIENT CHINESE NAMES IN EAST TURKESTAN AND CENTRAL ASIA AND THE TOCHARIAN QUESTION [1]

- ^ Wei Lan-Hai; Li Hui; Xu Wenkan (2013). "The separate origins of the Tocharians and the Yuezhi: Results from recent advances in archaeology and genetics" in Research Gate

- ^ A dictionary of Tocharian B by Douglas Q. Adams (Leiden Studies in Indo-European 10), xxxiv, 830 pp., Rodopi: Amsterdam – Atlanta, 1999. [2]

- ^ Sinor, Denis (1997). Aspects of Altaic Civilization III. Psychology Press. p. 237. ISBN 0-7007-0380-2. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

...it seems likely, the Wu-sun were an Indo-European, perhaps Iranian people...

- ^ Fan Ye, Chronicle on the 'Western Regions' from the Hou Hanshu. (transl. John E. Hill), 2011] "Based on a report by General Ban Yong to Emperor An (107–125 CE) near the end of his reign, with a few later additions." (20 December 2015)

- ^ "History of Central Asia: Early Eastern Peoples". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

... in the second half of the 2nd century bce the Xiongnu, at the height of their power, had expelled from their homeland in western Gansu (China) a people probably of Iranian stock, known to the Chinese as the Yuezhi and called Tokharians in Greek sources.

- ^ "Ancient Iran: The movement of Iranian peoples". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

At the end of the 3rd century, there began in Chinese Turkistan a long migration of the Yuezhi, an Iranian people who invaded Bactria about 130 bc, putting an end to the Greco-Bactrian kingdom there. (In the 1st century bc they created the Kushān dynasty, whose rule extended from Afghanistan to the Ganges River and from Russian Turkistan to the estuary of the Indus.)

- ^ Wei Lan-Hai; Li Hui; Xu Wenkan (2013). "The separate origins of the Tocharians and the Yuezhi: Results from recent advances in archaeology and genetics" in Research Gate [3]

- ^ Lebedynsky, Yaroslav (2007). Les nomades. Éditions Errance. p. 131. ISBN 9782877723466.

- ^ Macmillan Education (2016). Macmillan Dictionary of Archaeology. Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 369. ISBN 978-1349075898.[permanent dead link] "From that time until the HAN dynasty the Ordos steppe was the home of semi-nomadic Indo-European peoples whose culture can be regarded as an eastern province of a vast Eurasian continuum of Scytho-Siberian cultures."

- ^ Harmatta 1992, p. 348: "From the first millennium b.c., we have abundant historical, archaeological and linguistic sources for the location of the territory inhabited by the Iranian peoples. In this period the territory of the northern Iranians, they being equestrian nomads, extended over the whole zone of the steppes and the wooded steppes and even the semi-deserts from the Great Hungarian Plain to the Ordos in northern China."

- ^ https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/sites/silkroad/files/knowledge-bank-article/4%20Indo-European%20indications%20of%20Turkic%20ancestral%20home%20-%20Copy.pdf [dead link]

- ^ "IRAN v. PEOPLES OF IRAN (2) Pre-Islamic – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- ^ üdiger Schmitt in Encyclopædia Iranica, s.v. "Caspians"

- ^ Harmatta, János (January 1, 1994). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B. C. to A.D 250: Conclusion. UNESCO. p. 488. ISBN 9231028464. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

Their royal tribes and kings (shan-yii) bore Iranian names and all the Hsiung-nu words noted by the Chinese can be explained from an Iranian language of Saka type. It is therefore clear that the majority of Hsiung-nu tribes spoke an Eastern Iranian language.

Literature

[edit]- H. Bailey, "ARYA: Philology of ethnic epithet of Iranian people", in Encyclopædia Iranica, v, pp. 681–683, Online-Edition, Link Archived 2008-12-16 at the Wayback Machine

- A. Shapur Shahbazi, "Iraj: the eponymous hero of the Iranians in their traditional history" in Encyclopædia Iranica, Online-Edition, Link Archived 2007-03-11 at the Wayback Machine

- R. Curzon, "The Iranian Peoples of the Caucasus", ISBN 0-7007-0649-6

- Jahanshah Derakhshani, "Die Arier in den nahöstlichen Quellen des 3. und 2. Jahrtausends v. Chr.", 2nd edition, 1999, ISBN 964-90368-6-5 ("The Arians in the Middle Eastern sources of the 3rd and 2nd Millennia BC")

- Richard Frye, "Persia", Zurich, 1963

- Wei Lan-Hai; Li Hui; Xu Wenkan (2013). "The separate origins of the Tocharians and the Yuezhi: Results from recent advances in archaeology and genetics" in Research Gate [4]

External links

[edit]- [5] - Source texts of ancient Greek and Roman authors

- [6] - Strabo's work The Geography (Geographica). Book 11, Chapters 6 to 13, and Book 15, Chapters 2 and 3, are about regions dwelt by ancient Iranian peoples and tribes (each region has a chapter).

- List of Globally Famous People of Iran (M.I.T)