Philadelphia transit strike of 1944

Thomas E. Allen (left), an employee of the Philadelphia Transportation Company, training as a trolley operator with William Poisel. Until 1944, black workers were excluded from all non-menial jobs. | |

| Date | August 1–6, 1944 |

|---|---|

| Location | Philadelphia |

| Participants | White workers of the Philadelphia Transportation Company |

| Outcome | Strike broken as a result of the U.S. military intervention under the Smith–Connally Act |

The Philadelphia transit strike of 1944 was a sickout strike by white transit workers in Philadelphia that lasted from August 1 to August 6, 1944. The strike was triggered by the decision of the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC), made under prolonged pressure from the federal government in view of significant wartime labor shortages, to allow black employees of the PTC to hold non-menial jobs, such as motormen and conductors, that were previously reserved for white workers only.[1][2] On August 1, 1944, the eight black employees being trained as streetcar motormen were due to make their first trial run. That caused the white PTC workers to start a massive sickout strike.[1][3]

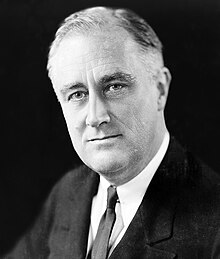

The strike paralyzed the public transport system in Philadelphia for several days, bringing the city to a standstill and crippling its war production. Although the Transport Workers Union (TWU) was in favor of allowing promotions of black workers to any positions they were qualified for, and opposed the strike, the union was unable to persuade the white PTC employees to return to work. On August 3, 1944, under the provisions of the Smith–Connally Act, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson to take control of the Philadelphia Transportation Company, and Major-General Philip Hayes was put in charge of its operations. After several days of unsuccessful negotiations with the strike leaders, Hayes issued an order that the striking workers return to work on August 7, 1944, and that those refusing to comply be fired, stripped of their military draft deferment, and denied job availability certificates by the War Manpower Commission for the duration of the war. This ultimatum proved effective and on August 7, the strike ended and the strikers returned to work. The black workers, whose pending promotions to non-menial jobs triggered the strike, were allowed to assume those jobs.

During the strike, despite considerable tensions, the city of Philadelphia remained mostly calm, and there were no major outbreaks of violence. All of the city's newspapers editorialized against the strike and the public was, by and large, opposed to the strike as well. Several of the strike leaders, including James McMenamin and Frank Carney, were arrested for violating the anti-strike act. The NAACP played an active role both in pressuring the PTC and the federal government to institute fair hiring practices at the PTC for several years before the strike and in maintaining the calm during the strike itself.

The strike received considerable attention in the national media. The Philadelphia transit strike of 1944 is one of the most high-profile instances of the federal government invoking the Smith–Connally Act.[4] The Act had been passed in 1943 over President Roosevelt's veto.[5]

Background

[edit]PTC and the union

[edit]

Since even before the official entry of the United States into World War II in December 1941, Philadelphia had been one on the major industrial war production centers in the U.S. By 1944 Philadelphia was regarded as the second largest war production center in the country (after Los Angeles).[1][6] During that period the black population of the city grew substantially, and tensions with the predominantly white population began to increase. The Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) ran the city's huge public transportation system, including subways, buses and trolleys; by the time of the strike, it carried over one million people per day.[1] By 1944, the PTC's eleven thousand strong workforce included 537 black employees.[7] However, the PTC's black workers had been restricted to holding menial jobs; none were allowed to serve as conductors or motormen – positions that were reserved for white employees.[7] As early as August 1941, black employees started pressuring the PTC for fairer employment practices that would allow upgrading of black workers to the more prestigious jobs reserved for whites. Their efforts were rebuffed by PTC management, who claimed that the current union contract contained a clause prohibiting any significant change in employment practices and customs without the union's approval (although the contract said nothing about race). The leader of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Employees Union (PRTEU), Frank Carney, proved to be equally reticent and claimed that he was not authorized by the union members to consider a request to allow promotions of black employees.[7]

Federal involvement

[edit]The black PTC employees enlisted the help of the NAACP and started lobbying the federal authorities, particularly the Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC), to intervene. The Fair Employment Practices Commission, created by an executive order of the President in 1941, was charged with ensuring non-discrimination employment practices by government contractors. Initially it was a fairly weak agency, but its authority was significantly strengthened in 1943 by a new executive order that required all government contracts to have a non-discrimination clause. As the war progressed, the manpower shortages were getting more severe. In January 1943 the PTC requested 100 white motormen from the United States Employment Service (USES),[8] which was a part of the War Manpower Commission (WMC). The WMC, aware that PTC had a pool of black employees seeking upgrading, asked the PTC to allow hiring of black employees for the vacant motormen positions. The PTC refused, again citing the "customs clause" of its union contract.[8][9] After a complaint from the NAACP, the matter landed at the FEPC, headed at the time by Malcolm Ross.

The FEPC made a series of unsuccessful attempts to convince the PTC management and the union leadership to change their stance and to allow promotions of black employees to non-menial jobs. The PTC eventually conceded that it would be willing to go along with the government's request and "employ Negroes, provided they are acceptable to fellow-workers",[9] but the PRTEU leadership, particularly Frank Carney, staunchly resisted. On November 17, 1943, the FEPC issued a directive requiring that PTC end its discriminatory employment practices and allow blacks to hold non-menial jobs.[9] The directive also required the PTC to review all job applications from June 1941 and redress earlier employment abuses based on racial discrimination. The union immediately protested and requested a public hearing, which took place on December 8, 1943.[10] At the hearing the union tried to make the argument that hiring blacks who had applied for the non-menial positions since June 1941 but were denied would adversely affect the seniority rights of the presently employed white workers. Malcolm Ross rejected that argument, pointing out that the seniority rights only begin when an employee is actually hired for a particular job. On December 29, 1943, FEPC issued a second directive, reinforcing the first one.[10]

In an attempt to deflect the pressure, Carney and PRTEU contacted Virginia congressman Howard W. Smith, who at the time was the Chair of the House Committee to Investigate Executive Agencies. Smith, known for his segregationist views and eager to embarrass and possibly destroy the FEPC,[11] quickly scheduled a hearing. In the meantime, the union informed the PTC that it refused to comply with the FEPC order, and the PTC management told Ross that, given the union's position, the PTC would not comply with the FEPC directive either.[10] The hearing in front of Smith's committee took place on January 11, 1944.[12] The hearing was inconclusive, with Ross reiterating the FEPC position, and the union representatives falling back on the "customs clause" and their claims about seniority issues. Several white workers testifying at the hearing predicted that there would be trouble and unrest if promotions of black employees at the PTC were allowed: "We are not going to accept them [the blacks] as fellow workers. ... We are not going to work with them. If anybody believe it, let them try it".[13] A petition, signed by 1776 workers, presented at the hearing, read: "Gentlemen: We, the white employees of the Philadelphia Transportation Co., refuse to work with Negroes as motormen, conductors, operators and station trainmen".[13]

Inter-union struggle

[edit]Following the January 11 congressional hearing, Malcolm Ross’s delay in enforcing the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) directive was not just a waiting game; it highlighted the complex landscape of labor relations and racial tensions within the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC). Between 1940 and 1945, Philadelphia saw a significant influx of Black residents, with nearly 36,000 new Black residents swelling the city’s Black population to almost 300,000. This rapid demographic shift heightened anxieties among white Philadelphians, particularly as Black workers pushed for better employment opportunities amidst labor shortages. The PTC, with a workforce of 11,000 employees, included only 537 Black employees, all relegated to menial roles such as cleaners, while white employees filled all operating positions, such as motormen and conductors, that came with greater status and visibility.

Despite early efforts by Black workers to advocate for promotions through channels like the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Employees Union (PRTEU), union leaders consistently cited a “customs clause” in their contracts to block any changes in employment practices. This clause, though not explicitly about race, allowed both the union and the company to maintain the status quo, effectively excluding Black employees from promotions. When the NAACP intervened, PTC management and PRTEU leadership continued to defer responsibility to each other, using the customs clause as justification for inaction.

The FEPC’s involvement marked a turning point. In response to PTC’s hiring of 100 new white motormen in early 1943, the War Manpower Commission urged the company to consider Black applicants, but PTC again cited the customs clause as grounds for refusal. With labor shortages growing critical, national attention on racial discrimination in wartime industries intensified, and the FEPC, bolstered by a partnership with the War Manpower Commission, began to push harder against PTC’s discriminatory policies.

Amid this escalating pressure, the March 1944 union election presented an opportunity for a shift in labor relations at PTC. The Transport Workers Union (TWU), a CIO affiliate, ran on a platform supporting the promotion of Black employees, contrasting sharply with the PRTEU’s racially exclusionary stance. Ultimately, the TWU won, securing more votes than both the PRTEU and the Amalgamated Association combined. However, despite this victory, resistance from white workers persisted, and the PTC continued to stall on implementing the FEPC’s directive. The ongoing contract negotiations between TWU and PTC became a prolonged struggle, emblematic of the deep-seated racial and labor tensions that still permeated Philadelphia’s transit system during the war.

Immediate run up to the strike

[edit]In view of growing labor shortages, on July 1, 1944 the War Manpower Commission made an important decision, ruling that from then on all hiring of male employees in the country was to be done through the United States Employment Service (USES).[10][14] By that time the USES followed strict anti-discrimination employment practices. The PTC management finally gave in and within a week posted notices about available skilled positions that would be open to all applicants, regardless of race.[10] The company accepted eight black applicants (three from the USES and five from its own ranks) to train as streetcar coachmen. Their training was to take place in late July, and they were to start taking an empty streetcar on the lines from August 1. It was that impending trial run of the streetcars by the eight black trainees that finally triggered the strike.[1]

As the news spread, resentment among the white PTC workers began to grow. There were postings on PTC bulletin boards urging non-compliance with the new policy, and a petition was circulated calling for a strike to protest job upgrades of black employees. There were also several meetings called by agitators for the strike to discuss the plan of action. Frank Carney played an active role in these meetings. At the last such meeting, on July 31, Carney announced that the "D-Day" for white workers had arrived.[3] The TWU and the NAACP representatives warned the PTC about impending trouble, but the company management ignored those warnings, maintaining that there was nothing to fear.[3][10]

Events of the strike

[edit]Start of the strike

[edit]At 4:00 a.m. on August 1, 1944 most trolleys, buses and subways in Philadelphia stopped running.[3][10] Strike agitators blocked access to PTC depots with vehicles and advised the arriving workers of a sickout strike. By noon of August 1 the entire PTC transportation system was paralyzed. James McMenamin, a veteran PTC white motorman, organized a 150-member strike steering committee and became one of the main leaders of the strike.[15] Frank Carney, the ousted union boss, was another key strike leader. At the end of the day the strikers held a large meeting, attended by more than 3,500 employees, outside the PTC carbarn on Luzerne Street.[15] The racial rhetoric was escalating. At the meeting, Frank Carney declared that driving a streetcar was a white man's job and said: "put the Negroes back where they belong, back on the roadway".[15] McMenamin declared that "the strike was a strictly black and white issue".[15]

The PTC's response to the strike was anemic and was interpreted by some contemporary observers and later historians as tacitly supporting the strike.[16] Arthur Mitten, chairman of the company's Industrial Relations Division, stopped by the Luzerne carbarn and asked the workers to return to work. Subsequently, he suggested that WMC temporarily suspend the non-discrimination order, and even brought a pile of freshly printed fliers with a suspension announcement to the WMC offices. However, the WMC officials refused to approve suspension of the FEPC order and Mitten's suspension fliers were not distributed.[15] On the morning of August 1, PTC officials immediately shut down the high-speed lines, even before the strike had spread, and instructed the company supervisors to stop selling tickets. The PTC left its carbarns open, which allowed the strikers to use the carbarns as rallying points and coordinating centers for their activities.[16] The company also cancelled the regularly scheduled meeting of its executive committee, where the response to the strike could have been discussed, and refused to join the TWU in a radio broadcast urging the strikers to return to work.[16]

The TWU officials denounced the strike and pleaded with the PTC employees to resume work, but without success. The city's mayor, Bernard Samuel, closed all alcohol-selling establishments in an effort to prevent drunken crowds. Governor Edward Martin followed suit and closed the state liquor stores in the area.[17] The city deployed its full police force, with extra police officers posted at major intersections and other vital points. The NAACP, as well as other black civic groups, worked energetically to maintain calm among the black people of Philadelphia. They distributed more than 100,000 posters in black sections of the city, which read "Keep Your Heads and Your Tempers! ... Treat other people as you would be treated".[18]

The strike continued on August 2. About 250 TWU members initiated a back-to-work movement but were quickly forced to back down by the strike's leaders and supporters.[17] At the end of the day, William H. Davis, head of the War Labor Board, wrote to President Roosevelt that the WLB had no jurisdiction over the situation and that it was up to the President to intervene.[19] Representatives of the WMC and the FEPC had reached a similar conclusion about the need for the President's intervention the day before.

Military takeover of the PTC

[edit]The Roosevelt administration felt that it needed to act quickly to stop the strike. War plants in Philadelphia reported debilitating absentee rates in their workforce due to the strike, which was causing significant damage to the city's war production. The military reported delays in delivery of fighter planes, radar equipment, flamethrowers and numerous other items.[20] Rear Admiral Milo Draemel complained that the strike so significantly slowed the war production in the area that "it could delay the day of victory".[20] The strike was also negatively affecting America's image abroad, particularly in Europe, where the U.S. was fighting Nazi Germany under the slogans of freedom and racial justice. Germany, as well as Japan, were apt to use every instance of racial unrest in the U.S. for propaganda purposes.[20] Official reaction by the White House was somewhat delayed by President Roosevelt's absence: at the time he was on a warship on his way from Hawaii to the Aleutian islands. At 7:45 p.m. on August 3, in his twenty-fifth seizure order under the Smith–Connally Act, President Roosevelt authorized the Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson to take control of the Philadelphia Transportation Company.[19] Major-General Philip Hayes, head of the Army's Third Service Command, was put in charge of the PTC's operations.

The troops were elements from the 309th[21] regiment of the 78th infantry division stationed in Virginia. The men were bivouacked in Fairmount Park, George's Hill, above Parkside Ave., West Philadelphia. Hayes acted quickly to take control of the situation. He posted the President's order on the PTC carbarns and announced that the Army hoped to avoid using the troops and would try to rely on the local and state police to the extent possible.[19] Hayes also announced that he had no intention of canceling or suspending the WMC hiring order. At 10:00 p.m. on August 3, mistakenly believing that the government had agreed to the strikers' demands, McMenamin declared the end of the strike. The mistake was quickly discovered, and over 1000 strikers voted in the early hours of August 4 to continue the strike.[19]

On August 4 limited transportation service resumed but largely dwindled as the day progressed. Hayes and his staff warned the strikers about the severe penalties provided by the Smith–Connally Act for disruption of the war production: the instigators could be subject to a fine of $5,000, one year in prison, or both.[22] This prospect was made more real when the United States Attorney General Francis Biddle started an inquiry into possible violations of federal laws by the strike organizers.[22][23] On August 4 the strike committee again voted to continue the strike, but, in view of the possible Smith–Connally Act penalties, told the workers to make up their own minds and follow the committee if they chose. The maneuver worked and the strike continued.[22]

On Saturday, August 5, with his patience exhausted, Hayes moved 5,000 army troops into the city. He announced that they would operate all idle PTC vehicles and ride as guards on active vehicles. He also made a plea to the strikers to support the war effort: "We cannot kill any Germans or Japs with the troops who drive transit vehicles in Philadelphia".[22] Later on August 5, Hayes issued an ultimatum to the strikers, which was posted at all carbarns. The PTC workers were given a deadline of 12:01 a.m. on August 7 to resume their work.[24] Those who refused would be fired and refused the WMC job availability certificates for the duration of the war; those between the ages of 18 and 37 would also lose their military draft deferments.[1][24] The Justice Department obtained federal warrants for McMenamin, Carney and two other strike leaders; they were quickly arrested, and McMenamin finally told his followers to return to work on Monday, August 7, as the government demanded.[24] However, he expressed no regret for his actions before and during the strike.[25]

The strike was essentially over. On Sunday, August 6, the PTC workers signed cards pledging to return to work on Monday. On Monday, August 7, normal PTC operations resumed and the absentee rate was significantly lower than on a typical work day before the strike.[24] As the strike ended, twenty-four strikers were dropped from the PTC rolls and six were immediately drafted into the military.[26]

Actions of the local government

[edit]The enhanced police presence throughout the city during the strike helped to keep the calm, and the restrained approach of the police officers generally won praise from all sides,[27][28] even though many of the policemen were seen as sympathetic to the striking white workers.[29] The administration of Philadelphia's Republican mayor Bernard Samuel was also seen as quietly sympathetic to the strikers. Throughout the strike, Mayor Samuel, who was also a member of the PTC board of directors, avoided any attempts of mediation. He refused to call a meeting of the PTC board of directors or to discuss the crisis with the TWU leaders. The mayor denied police protection to the two TWU officials who were willing to travel throughout the city and advocate an end to the strike.[29] Samuel also refused to grant air time to War Production Board representatives who wanted to make a radio plea to end the strike.[29] On August 2, the mayor declined, without an explanation, the NAACP request for permission to send two sound-trucks into black neighborhoods to broadcast appeals for calm. The city's black population felt disappointed and disenchanted with the actions of the local administration.[20]

Public reaction

[edit]Except for a few incidents, the city of Philadelphia remained calm during the strike and, despite considerable fears of race riots, there were no major outbreaks of violence. At the start of the strike there were some incidents of vandalism and store window smashing, and the police arrested about 300 people, most of them blacks.[1] In a nastier episode, three white motorists drove a car through a black neighborhood and, without stopping or warning, shot at a 13-year-old black boy, who received non-critical injuries.[30] The most visible episode of unrest came when a black war factory worker, whose brother was in the Army, threw a paperweight at the Liberty Bell shouting "Liberty Bell, oh Liberty Bell—liberty, that's a lot of bunk!"[1] He was arrested and sent by the magistrate for a psychiatric evaluation. However, by and large, calm prevailed and there were no major outbreaks of violence and no deaths or critical injuries among the public.[31]

The public opinion and the media in the city were overwhelmingly against the strikers. All the city's newspapers ran editorials denouncing the strike, which was perceived as unpatriotic and harmful to the war effort; a number of editorials also decried the racial nature of the strike.[32] Most letters to the editor condemned the strike. The radio stations in the city denounced the strike as well,[10] as did the national press. The New York Times wrote "It would be hard to find in the whole history of American labor a strike in which so much damage has been done for so base a purpose".[33] A Wall Street Journal editorial condemned the strike but stated that the powers exercised by the government in ending the strike were only justified by the war time conditions.[34] The conservative-leaning Los Angeles Times and the Chicago Tribune, while denouncing the strike, tried to put the blame for causing it on the CIO-affiliated Transport Workers Union, and accused the Roosevelt administration of acting too slowly because of its support for the CIO.[35][36]

While critical of the strike, the public did not necessarily support the cause of equal employment opportunities for black workers. A public opinion poll conducted in Philadelphia during the strike showed that only a slim majority of the city's population felt that blacks should be hired as motormen and conductors, but that a significant majority opposed having a strike over this issue.[37]

The strikers directed much of their anger at the federal government, which they accused of overreaching and of refusing to listen to legitimate complaints by white workers. This view resonated with many white Philadelphians[38] and with conservative politicians nationally. On August 8, Senator Richard Russell from Georgia, one of the leaders of the conservative coalition in Congress, gave a seventy-minute speech on the Senate floor, blaming the FEPC for causing the strike. Russell finished his speech by calling the FEPC "the most dangerous force in existence in the United States today".[26] Some of the newspapers in the South also blamed the incident on the Roosevelt administration and even on First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, with Savannah News claiming that the episode was caused by "Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt's persistent efforts to force social equality on the American people".[39]

Aftermath

[edit]

Starting with August 7, the PTC resumed its normal schedule and there were no further disruptions. The troops remained in Philadelphia for another week and a half and rode as guards on PTC vehicles, but encountered no further problems. Seven of the eight black trainees resumed their training (one withdrew voluntarily because his duties as Jehovah's Witness minister conflicted with the PTC work schedule).[40] On August 9, the PTC finally agreed to a favorable contact which had been approved by the TWU in June.[24] On August 17, Hayes returned full control of the public transportation network to the PTC.[24][41] Subsequent integration of black employees into the PTC workforce proceeded with no further trouble. By December 1944 the PTC had 18 black streetcar operators. An attractive new union contract helped quell the remaining discontent among the white PTC workers. Within a year, the company had over 900 black employees working in a variety of positions, including as drivers and conductors.[2]

The NAACP later blamed the PTC management for intentionally dragging its feet on the contract that the TWU approved in late June.[10] The NAACP claimed that the PTC management had hoped to undermine the TWU's position with the workers and to possibly oust TWU in favor of the more pliable PRTEU. The PTC was aware that the Smith–Connally Act forbade strikes harming war production and that if, with a contract impasse, TWU itself had initiated a contract strike, the union might have been tossed out. This analysis of the situation was shared later by several historians, particularly by James Wolfinger.[2] Another historian, Alan M. Winkler, also had a largely negative view of the company's role in the conflict and concluded that PTC management, while not overtly conspiring with the strikers, reacted feebly to the strike and tried to opportunistically exploit the situation and the racist attitudes of many white workers for their own purposes.[37]

The leaders of the strike, including McMenamin and Carney, were charged in federal court under the Smith–Connally Act; some thirty strikers were also indicted later. The federal grand jury was convened on August 9 and heard testimony for two months.[42] However, the grand jury returned inconclusive findings; their report stated that most of the striking workers knew nothing about the strike at the start, and blamed a few instigators for escalating the situation, but did not detail the instigators' activities. The report was also critical of the PTC's response to the strike, characterizing it as inadequate and ineffective. The government dropped its charges against the defendants on March 12, 1945, with most of them pleading nolo contendere and receiving a fine of $100 each.[42]

As labor historian James Wolfinger observed, the strike "demonstrated the profound racial cleavages, that divided the working class, not just in the South but across the nation".[43]

Although brief, the Philadelphia transit strike of 1944 had significant negative impact on the war effort, resulting in a loss of four million work hours in war plants alone.[44] The War Manpower Commission estimated that the Philadelphia strike cost the nation's war production the equivalent of 267 Flying Fortresses or five destroyers.[45] Malcolm Ross later characterized the strike as "the most expensive racial dispute of World War II".[46] The strike also exposed the limitations of the FEPC's power. The FEPC did not possess the final authority to enforce its decisions and only the executive intervention of the President made the resolution of the dispute possible.[47] Nevertheless, the strike demonstrated that a combination of black activism, particularly by the NAACP, together with resolute federal policies, were able to break long standing racial barriers in employment.[43]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Trouble in Philadelphia, TIME

- ^ a b c Wolfinger, Philadelphia Transit Strike (1944)

- ^ a b c d Winkler, p. 80

- ^ Daniel J. Leab, The Labor history reader, University of Illinois Press, 1985, ISBN 0-252-01197-X; p. 399

- ^ Peter G. Renstrom, The Stone court: justices, rulings, and legacy. ABC–CLIO Supreme Court handbooks, 2001, ISBN 1-57607-153-7; p. 244

- ^ Editorial: The Philadelphia transit Strike, Evening Independent, August 7, 1944

- ^ a b c Winkler, p. 74

- ^ a b Winkler, p. 75

- ^ a b c Spaulding, p. 282

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Spaulding, p. 283

- ^ Joe William Trotter, Eric Ledell Smith, African Americans in Pennsylvania: shifting historical perspectives, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-271-01686-8 p. 368

- ^ Winkler, p. 77

- ^ a b Winkler, p. 78

- ^ Winkler, p. 79

- ^ a b c d e Winkler, p. 81

- ^ a b c Wolfinger, Philadelphia divided: race & politics in the City of Brotherly Love, p. 144

- ^ a b Winkler, p. 82

- ^ Ross, pp. 97–98

- ^ a b c d Winkler, p. 83

- ^ a b c d Wolfinger, Philadelphia divided: race & politics in the City of Brotherly Love, pp. 149–150

- ^ //

- ^ a b c d Winkler, p. 84

- ^ Federal Hearings on Philadelphia Strike Set. Prescott Evening Courier, August 4, 1944, p. 1

- ^ a b c d e f Winkler, p. 85

- ^ Arrested leaders ask Philadelphia strikers go back; act on ultimatum, New York Times, August 6, 1944, p. 1

- ^ a b Herbert Hill, Black labor and the American legal system: race, work, and the law, University of Wisconsin Press, 1985, ISBN 0-299-10590-3; p. 305

- ^ Spaulding, p. 301

- ^ Wolfinger, Philadelphia divided: race & politics in the City of Brotherly Love, p. 166

- ^ a b c Wolfinger, Philadelphia divided: race & politics in the City of Brotherly Love, p. 148

- ^ Spaulding, p. 281

- ^ Winkler, pp. 86 – 87

- ^ Winkler, p. 87

- ^ Lessons from Philadelphia, The New York Times, August 7, 1944, p. 14

- ^ Control Means Control, Wall Street Journal, Aug 8, 1944

- ^ The Philadelphia Strike as an Object Lesson, Los Angeles Times, August 4, 1944, p. A4

- ^ The Philadelphia strike, Chicago Daily Tribune, August 4, 1944, p. 10

- ^ a b Winkler, pp. 88–89

- ^ Wolfinger, Philadelphia divided: race & politics in the City of Brotherly Love, p. 158

- ^ Doris Kearns Goodwin, No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II, Simon & Schuster, 1995, ISBN 0-684-80448-4; pp. 539–540

- ^ Negro trainee quits tram job in Philadelphia, Chicago Tribune, August 17, 1944, p. 9

- ^ Philadelphia lines returned by the Army, New York Times, August 18, 1944, p. 9

- ^ a b Winkler, p. 86

- ^ a b James Wolfinger, World War II hate strikes, pp. 126–137. In: The encyclopedia of strikes in American history, Aaron Brenner, Benjamin Day, Immanuel Ness (editors), M.E. Sharpe, 2009, ISBN 0-7656-1330-1; p. 130

- ^ Winkler, p. 89

- ^ Strike Loss Equivalent to 5 Destroyers of 267 Planes, Gettysburg Times, August 8, 1944, p. 1

- ^ Ross, p. 85

- ^ Ross, p. 94

References

[edit]- Ross, Malcolm, All Manner of Men, Greenwood Press, New York, 1969. ISBN 0-8371-1047-5

- Spaulding, Theodore, Philadelphia's Hate Strike, The Crisis, September 1944, pp. 281–283, 301

- Trouble in Philadelphia, TIME, August 14, 1944. Accessed July 24, 2010

- Winkler, Allan M., The Philadelphia Transit Strike of 1944, Journal of American History, Vol. 59, No. 1 (Jun., 1972), pp. 73–89

- Wolfinger, James, Philadelphia Transit Strike (1944), Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-class History, Eric Arnesen (Editor), Vol. 1, pp. 1087–1088. Taylor & Francis, 2006. ISBN 0-415-96826-7

- Wolfinger, James, Philadelphia divided: race & politics in the City of Brotherly Love, Ch. 6, The Philadelphia Transit Strike, pp. 142–177, University of North Carolina, 2007. ISBN 0-8078-3149-2

- Egan, Charles E. “Roosevelt Orders Army to Take Over Philadelphia Lines.” New York Times (1923-Current File), August 4, 1944.

External links

[edit]- March protesting white trolley workers strike against black trolley operators, Philadelphia, PA., August 1944 (Photo), ExplorePAhistory.com

- African American James Stewart, a former musician, receives instruction on how to operate a Philadelphia Transit Company trolley car, Philadelphia, PA, July 31, 1944 (Photo). ExplorePAhistory.com

- James Wolfinger, ‘Liberty … That’s a lot of bunk!’: the meaning of the 1944 Philadelphia transit strike to black Philadelphia. www.historycooperative.org

- 1944 in Pennsylvania

- 1944 labor disputes and strikes

- 1944 in transport

- August 1944 events in the United States

- 1940s in Philadelphia

- History of labor relations in the United States

- Anti-black racism in Pennsylvania

- Transportation labor disputes in the United States

- Labor disputes in Pennsylvania

- Amalgamated Transit Union

- Labour history of World War II