Politics of Peru

|

|---|

|

|

The politics of the Republic of Peru takes place in a framework of a unitary semi-presidential representative democratic republic,[1][2] whereby the President of Peru is both head of state and head of government, and of a pluriform multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the President and the Government. Legislative power is vested in both the Government and the Congress. The Judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature. The Economist Intelligence Unit rated Peru a "hybrid regime" in 2022.[3][needs update]

Traditionally weak political parties saw their support collapse further in Peru since 2000, paving the way for the rise of personalist leaderships.[4][5] The political parties in the congress of Peru are, according to political scientist Lucía Dammert, "agglomerations of individual and group interests more than solid and representative parties".[5]

The historian Antonio Zapata describes Peru as a "right-wing country"; the only left-wing government in contemporary history until the election of Pedro Castillo in 2021 was that of Juan Velasco Alvarado (1968-1975), author of an agrarian reform and the nationalization of strategic sectors.[6] Peru is also one of the most socially conservative nations in Latin America.[7]

Currently, almost all major media and political parties in the country are in favour of economic liberalism.[6] Those opposed to the neoliberal status quo or involved in left-wing politics are often targeted with fear mongering attacks called terruqueos, where individuals or groups are associated with terrorists involved with the internal conflict in Peru.[8][9]

History

[edit]The weakness of political parties in Peruvian politics has been recognized throughout the nation's history, with competing leaders fighting for power following the collapse of the Spanish Empire's Viceroyalty of Peru.[10][11][4] The Peruvian War of Independence saw aristocrats with land and wealthy merchants cooperate to fight the Spanish Empire, though the aristocrats would later obtain greater power and lead an oligarchy headed by caudillos that defended the existing feudalist haciendas.[4] During the time of the Chincha Islands War, guano extraction in Peru led to the rise of an even wealthier aristocracy that established a plutocracy.[4] Anarchist politician Manuel González Prada accurately detailed that parties in Peru shortly after the War of the Pacific were controlled by a wealthy oligarchy that used candidate-based political parties to control economic interests; a practice that continues to the present day.[4] This oligarchy was supported by the Catholic Church, which would ignore inequalities in Peru and instead assist governments with appeasing the impoverished majority.[4] At this time, the armed forces of Peru were seen by the public as ensuring territorial sovereignty and order, granting military leaders the ability to blame political parties and justify coup d'états against established leaders of the nation who were facing socioeconomic difficulties.[11] This led to a pattern throughout Peru's political history of an elected leader drafting and proposing a policy while the military would later overthrow the said leader, adopting and implementing the elected official's proposals.[11] Combatting ideologies of indigenismo of the majority and the elite holding Europhile values would also arise at the end of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century.[4]

Following industrialization and World War I, economic expansion in Peru resulted with rural groups demanding more interaction with the wealthy urban areas and embracing indigenismo.[4] Labor and student movements – especially the anarcho-syndicalist Peruvian Regional Workers' Federation – would arise at this time while nearly overtaking the existing oligarchical structure, though the coup and subsequent dictatorship of Augusto B. Leguía for the next decade would quash hopes for further progress.[4] During the Leguía dictatorship emerged two political thinkers inspired by González Prada; José Carlos Mariátegui and Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre.[4] In 1924 from Mexico, university reform leaders in Peru who had been forced into exile by the government founded the American People's Revolutionary Alliance, which had a major influence on the country's political life. APRA is thus largely a political expression of the university reform and workers' struggles of the years 1918–1920. The movement draws its influences from the Mexican Revolution and its 1917 Constitution – particularly on issues of agrarianism and indigenism – and to a lesser extent from the Russian Revolution. Its leader, Haya de la Torre, declares that APRA as a "Marxist interpretation of the American reality", it nevertheless moves away from it on the question of class struggle and on the importance given to the struggle for the political unity of Latin America.[12] In 1928, the Peruvian Socialist Party was founded, notably under the leadership of José Carlos Mariátegui, himself a spectator of the European socialist movements who maintained relationships with the Communist Party of Italy, including the leadership of Palmiro Togliatti and Antonio Gramsci. Shortly afterwards in 1929, the party created the General Confederation of Workers. Following the assassination of President Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro in 1933 by an Aprista, APRA was persecuted in Peru. Persecution of APRA persisted until about 1956 when it became allied with the elite in Peru.[4]

Following World War II, the military's ideology began to distance itself from the wealthy elite when the Center of High Military Studies began to promote studies of Manuel González Prada and José Carlos Mariátegui, creating officers that viewed the elite as sacrificing national sovereignty in order to acquire foreign capital and resulted with an undeveloped, reliant nation.[4] Thus in 1963, Fernando Belaúnde Terry was elected president and proposed the first pro-worker and peasant policies for Peru, though he was overthrown by General Juan Velasco Alvarado in 1968, who implemented Belaúnde's policies in his own unique manner.[11] The Shining Path guerilla group would also emerge in 1968 led by Abimael Guzmán, beginning the internal conflict in Peru between the state and Shining Path forces. During the Lost Decade of the 1980s and internal conflict, political parties became weaker once again.[10][11] Angered by President Alan García's inability to combat the crises in the nation, the armed forces began planning a coup to establish a neoliberal government in the late 1980s with Plan Verde.[13][14] Peruvians shifted their support for authoritarian leader Alberto Fujimori, who was supported by the military following his win in the 1990 Peruvian general election.[10][11]

Fujimori essentially adopted the policies outlined in the military's Plan Verde and turned Peru into a neoliberal nation.[14][15] Fujimori's civil-military government established sentiments in Peru that politics were slower than brute military force while governing.[11] The 1979 Constitution was changed after the Fujimori's self-coup where the president dissolved the Congress and established the new 1993 Constitution. One of the changes to the 1979 Constitution was the possibility of the president's immediate re-election (Article 112) which made possible the re-election of Fujimori in the following years. After Fujimori's resignation, the transitional government of Valentín Paniagua changed Article 112 and called for new elections in 2001 where Alejandro Toledo was elected.

However, following the fall of the Fujimori government, Peru still lacked strong political parties, leaving the nation vulnerable to populist outsider politicians lacking experience.[10] Regional parties then grew to become more popular as foreign investment increased during the 21st century, though their service to the elites sowed public distrust.[11] On 28 July 2021, left-wing candidate Pedro Castillo was sworn in as the new President of Peru after a narrow win in a tightly contested run-off election.[16] On 7 December 2022, the congress removed President Castillo from office. He was replaced by Vice President Dina Boluarte, the country's first female president.[17]

Allegations of corruption in politics

[edit]Exceptionally many Presidents of Peru have been ousted from office or imprisoned on allegations of corruption over the past three decades. Alberto Fujimori is serving a 25-year sentence in prison for commanding death squads that killed civilians in a counterinsurgency campaign during his tenure (1990-2000). He was later also found guilty of corruption. Former president Alan García (1985-1990 and 2006–2011) committed suicide in April 2019 when Peruvian police arrived to arrest him over allegations he participated in Odebrecht bribery scheme. Former president Alejandro Toledo is accused of allegedly receiving bribe from Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht during his government (2001-2006). Former president Ollanta Humala (2011-2016) is also under investigation for allegedly receiving bribe from Odebrecht during his presidential election campaign. Humala's successor Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (2016-2018) remains under house arrest while prosecutors investigate him for favoring contracts with Odebrecht. Former president Martín Vizcarra (2018-2020) was ousted by Congress after media reports alleged he had received bribes while he was a regional governor years earlier.[18][19]

Executive branch

[edit]

| Office | Name | Party | Since |

|---|---|---|---|

| President | Dina Boluarte | Independent | 7 December 2022 |

| First Vice President | Vacant | 7 December 2022 | |

| Second Vice President | Vacant | 7 May 2020 | |

| Prime Minister | Gustavo Adrianzén | Independent | 6 March 2024 |

Under the current constitution, the president is the head of state and government. The president is elected for a five-year term and may not immediately be re-elected.[20] All citizens above the age of eighteen are entitled and in fact compelled to vote. The first and second vice presidents also are popularly elected but have no constitutional functions unless the president is unable to discharge his duties.

The President appoints the Prime Minister (Primer Ministro) and the Council of Ministers (Consejo de Ministros, or Cabinet), which is individually and collectively responsible both to the president and the legislature.[1][2] All presidential decree laws or draft bills sent to Congress must be approved by the Council of Ministers.

Legislative branch

[edit]

The legislative branch consists of a unicameral Congress (Congreso) of 130 members. elected for a five-year term by proportional representation In addition to passing laws, Congress ratifies treaties, authorizes government loans, and approves the government budget. The president has the power to block legislation with which the executive branch does not agree.

Political parties and elections

[edit]Like other Latin American nations, political parties in Peru since its revolutionary period have been weak and centered around a candidate instead of policy, with parties selecting a candidate with the most wealth that they can bring to support the organization.[10][11][4] The lack of popular political parties led to the rise of populist authoritarian leaders.[10] With the growth of media and a large informal population, Peru has continued to ignore the need for political parties.[10] Political parties exist mainly through conflict, holding a goal to damage opposing parties while ignoring policy.[11]

Presidential election

[edit]

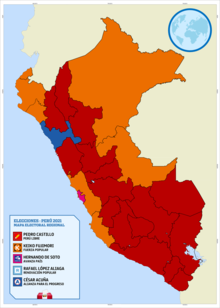

The first round was held on 11 April.[21][22] The first exit polls published indicated that underdog nominee Pedro Castillo of Free Peru had placed first in the first round of voting with approximately 16.1% of the vote, with Hernando de Soto and Keiko Fujimori tying with 11.9% each.[22] Yonhy Lescano, Rafael López Aliaga, Verónika Mendoza, and George Forsyth followed, with each receiving 11.0%, 10.5%, 8.8%, and 6.4%, respectively.[22] César Acuña and Daniel Urresti received 5.8% and 5.0%, respectively, while the rest of the nominees attained less than 3% of the popular vote.[23][24]

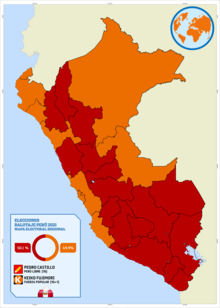

In the second round, Castillo defeated Fujimori by just 44,263 votes, winning by 50.13% to 49.87%. Castillo was officially designated as president-elect of Peru on 19 July 2021, a little over a week before he was to be inaugurated.[25]

By department

[edit]| Department | Castillo Free Peru |

Fujimori Popular Force |

López Aliaga Popular Renewal |

De Soto Go on Country |

Lescano Popular Action |

Mendoza Together for Peru |

Other candidates |

Valid votes |

Turnout | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Amazonas | 34,411 | 26.1% | 17,805 | 13.5% | 8,269 | 6.3% | 4,433 | 3.4% | 12,698 | 9.6% | 8,887 | 6.7% | 45,557 | 34.5% | 132,060 | 60.1% |

| Ancash | 110,620 | 23.4% | 67,394 | 14.3% | 42,312 | 9.0% | 34,562 | 7.3% | 38,911 | 8.2% | 39,786 | 8.4% | 138,200 | 29.3% | 471,785 | 69.3% |

| Apurimac | 88,812 | 53.4% | 10,879 | 6.5% | 7,768 | 4.7% | 6,531 | 3.9% | 15,649 | 9.4% | 15,368 | 9.2% | 21,179 | 12.7% | 166,186 | 69.4% |

| Arequipa | 256,224 | 32.2% | 40,216 | 5.1% | 71,053 | 8.9% | 148,793 | 18.7% | 88,708 | 11.1% | 55,269 | 6.9% | 135,448 | 17.0% | 795,711 | 78.8% |

| Ayacucho | 130,224 | 52.0% | 17,751 | 7.1% | 11,490 | 4.6% | 8,995 | 3.6% | 20,315 | 8.1% | 24,506 | 9.8% | 37,269 | 14.9% | 250,550 | 68.6% |

| Cajamarca | 232,418 | 44.9% | 54,962 | 10.6% | 31,129 | 6.0% | 25,156 | 4.9% | 38,677 | 7.5% | 29,746 | 5.7% | 105,374 | 20.4% | 517,462 | 62.6% |

| Callao | 33,750 | 6.4% | 79,699 | 15.2% | 78,066 | 14.9% | 78,920 | 15.0% | 34,965 | 6.7% | 38,233 | 7.3% | 181,634 | 34.6% | 525,267 | 75.2% |

| Cusco | 232,178 | 38.2% | 27,132 | 4.5% | 29,618 | 4.9% | 40,423 | 6.6% | 60,659 | 10.0% | 123,397 | 20.3% | 94,626 | 15.6% | 608,033 | 73.5% |

| Huancavelica | 79,895 | 54.2% | 8,449 | 5.7% | 5,060 | 3.4% | 4,591 | 3.1% | 16,727 | 11.3% | 10,091 | 6.8% | 22,574 | 15.3% | 147,387 | 67.6% |

| Huanuco | 110,978 | 37.6% | 32,827 | 11.1% | 33,787 | 11.4% | 15,822 | 5.4% | 22,565 | 7.6% | 15,556 | 5.3% | 63,688 | 21.6% | 295,223 | 68.3% |

| Ica | 56,597 | 14.0% | 62,055 | 15.3% | 46,098 | 11.4% | 39,929 | 9.8% | 39,461 | 9.7% | 30,602 | 7.5% | 130,887 | 32.3% | 405,629 | 76.0% |

| Junin | 131,438 | 22.9% | 80,057 | 13.9% | 52,599 | 9.2% | 54,124 | 9.4% | 66,214 | 11.5% | 52,270 | 9.1% | 137,396 | 23.9% | 574,098 | 71.9% |

| La Libertad | 90,078 | 11.5% | 131,441 | 16.8% | 95,765 | 12.2% | 84,444 | 10.8% | 47,218 | 6.0% | 37,372 | 4.8% | 296,598 | 37.9% | 782,916 | 68.9% |

| Lambayeque | 73,279 | 12.9% | 121,263 | 21.4% | 86,126 | 15.2% | 50,087 | 8.8% | 51,467 | 9.1% | 28,866 | 5.1% | 155,480 | 27.4% | 566,568 | 71.4% |

| Lima | 416,537 | 7.8% | 753,785 | 14.2% | 869,950 | 16.4% | 870,582 | 16.4% | 362,668 | 6.8% | 431,425 | 8.1% | 1,602,623 | 30.2% | 5,307,570 | 74.6% |

| Loreto | 15,432 | 4.9% | 51,900 | 16.6% | 16,378 | 5.3% | 18,816 | 6.0% | 34,773 | 11.2% | 19,502 | 6.3% | 155,025 | 49.7% | 311,826 | 61.0% |

| Madre de Dios | 23,945 | 37.1% | 7,278 | 11.3% | 4,041 | 6.3% | 3,996 | 6.2% | 6,601 | 10.2% | 4,372 | 6.8% | 14,341 | 22.2% | 64,574 | 71.1% |

| Moquegua | 33,665 | 34.4% | 4,617 | 4.7% | 6,832 | 7.0% | 10,183 | 10.4% | 15,412 | 15.7% | 7,190 | 7.3% | 20,027 | 20.5% | 97,926 | 77.2% |

| Pasco | 34,187 | 34.2% | 12,607 | 12.6% | 8,009 | 8.0% | 5,102 | 5.1% | 11,871 | 11.9% | 6,896 | 6.9% | 21,324 | 21.3% | 99,996 | 63.6% |

| Piura | 70,968 | 10.1% | 173,891 | 24.8% | 68,316 | 9.8% | 63,842 | 9.1% | 51,223 | 7.3% | 44,576 | 6.4% | 227,714 | 32.5% | 700,530 | 66.8% |

| Puno | 292,218 | 47.5% | 17,514 | 2.8% | 15,918 | 2.6% | 21,665 | 3.5% | 175,712 | 28.5% | 35,484 | 5.8% | 57,010 | 9.3% | 615,521 | 81.9% |

| San Martin | 67,000 | 21.4% | 46,699 | 14.9% | 26,561 | 8.5% | 21,825 | 7.0% | 31,498 | 10.0% | 17,122 | 5.5% | 102,765 | 32.8% | 313,470 | 69.2% |

| Tacna | 64,521 | 33.2% | 9,363 | 4.8% | 17,842 | 9.2% | 21,000 | 10.8% | 28,696 | 14.8% | 14,068 | 7.2% | 38,779 | 20.0% | 194,269 | 77.8% |

| Tumbes | 7,613 | 7.7% | 36,403 | 37.1% | 8,799 | 9.0% | 7,123 | 7.3% | 7,046 | 7.2% | 5,242 | 5.3% | 26,015 | 26.5% | 98,241 | 74.6% |

| Ucayali | 26,339 | 14.0% | 40,510 | 21.5% | 14,981 | 8.0% | 11,124 | 5.9% | 14,359 | 7.6% | 15,092 | 8.0% | 65,965 | 35.0% | 188,370 | 66.3% |

| Peruvians Abroad | 10,602 | 6.6% | 22,887 | 14.1% | 34,767 | 21.5% | 21,552 | 13.3% | 11,617 | 7.2% | 21,185 | 13.1% | 39,146 | 24.2% | 161,756 | 22.8% |

| Total | 2,723,929 | 18.9% | 1,929,384 | 13.4% | 1,691,534 | 11.8% | 1,673,620 | 11.6% | 1,305,710 | 9.1% | 1,132,103 | 7.9% | 3,936,644 | 27.4% | 14,392,924 | 70.0% |

| Source: ONPE (100% counted) | ||||||||||||||||

Parliamentary elections

[edit]

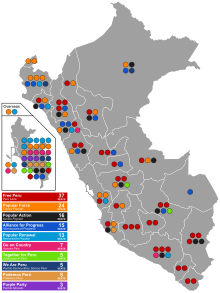

The Popular Action, the largest party in the previous legislature, lost some of its seats, and previous parliamentary parties like Union for Peru (UPP) and the Broad Front (FA) had their worst results ever, attaining no representation.[26] The Peruvian Nationalist Party of former President Ollanta Humala and National Victory of George Forsyth (who led polling for the presidential election earlier in the year) failed to win seats as well.[26] New or previously minor parties such as Free Peru, Go on Country and Together for Peru and Popular Renewal, the successor of National Solidarity, had good results, with Free Peru becoming the largest party in Congress.[26] Contigo, the successor to former president Pedro Pablo Kuczynski's Peruvians for Change party, failed to win a seat once again and received less than 1% of the vote.[26] On 26 July, two days before Castillo was sworn in as Peru's President, an opposition alliance led by Popular Action member María del Carmen Alva successfully negotiated an agreement to gain control of Peru's Congress.[27]

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | |

| Free Peru | 1,724,354 | 13.41 | 37 | +37 | |

| Popular Force | 1,457,694 | 11.34 | 24 | +9 | |

| Popular Renewal | 1,199,705 | 9.33 | 13 | +13 | |

| Popular Action | 1,159,734 | 9.02 | 16 | −9 | |

| Alliance for Progress | 969,726 | 7.54 | 15 | −7 | |

| Go on Country – Social Integration Party | 969,092 | 7.54 | 7 | +7 | |

| Together for Peru | 847,596 | 6.59 | 5 | +5 | |

| We Are Peru | 788,522 | 6.13 | 5 | −6 | |

| Podemos Perú | 750,262 | 5.83 | 5 | −6 | |

| Purple Party | 697,307 | 5.42 | 3 | −6 | |

| National Victory | 638,289 | 4.96 | 0 | New | |

| Agricultural People's Front of Peru | 589,018 | 4.58 | 0 | −15 | |

| Union for Peru | 266,349 | 2.07 | 0 | −13 | |

| Christian People's Party | 212,820 | 1.65 | 0 | 0 | |

| Peruvian Nationalist Party | 195,538 | 1.52 | 0 | New | |

| Broad Front | 135,104 | 1.05 | 0 | −9 | |

| Direct Democracy | 100,033 | 0.78 | 0 | 0 | |

| National United Renaissance | 97,540 | 0.76 | 0 | 0 | |

| Peru Secure Homeland | 54,859 | 0.43 | 0 | 0 | |

| Contigo | 5,787 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 12,859,329 | 100.00 | 130 | 0 | |

| Valid votes | 12,859,329 | 72.56 | |||

| Invalid votes | 2,737,099 | 15.44 | |||

| Blank votes | 2,126,712 | 12.00 | |||

| Total votes | 17,723,140 | 100.00 | |||

| Registered voters/turnout | 25,287,954 | 70.09 | |||

| Source: ONPE, Ojo Público | |||||

Judicial branch

[edit]

The judicial branch of government is headed by a 16-member Supreme Court seated in Lima. The National Council of the Judiciary appoints judges to this court.

The Constitutional Court (Tribunal Constitucional) interprets the constitution on matters of individual rights. Superior courts in regional capitals review appeals from decisions by lower courts. Courts of first instance are located in provincial capitals and are divided into civil, penal, and special chambers. The judiciary has created several temporary specialized courts in an attempt to reduce the large backlog of cases pending final court action.

Peru's legal system is based on civil law system. Peru has not accepted compulsory ICJ jurisdiction. In 1996 a human rights ombudsman's office (defensor del pueblo) was created to address human rights issues.

Administrative divisions

[edit]Peru's territory, according to the Regionalization Law which was passed on 18 November 2002, is divided into 25 regions (regiones). These regions are subdivided into provinces, which are composed of districts. There are a total of 180 provinces and 1747 districts in Peru.

Lima Province is not part of any political region.

Organizations

[edit]Armed groups

[edit]Leftist guerrilla groups include Shining Path, the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA). Both Shining Path and MRTA are considered terrorist organizations.

Regional groups

[edit]Regional groups representing peasant and indigenous groups exist in the outlying provinces, often working to promote autonomy.[28] Groups promoting autonomy agreements with larger states possibly existed since the Inca Empire and such sentiments of independence have continued among local communities to current times.[28]

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs)

[edit]This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: It is not clear which NGOs are being discussed, or how broadly this description applies to NGOs in general. (August 2014) |

In the early 1970s and 1980s, many grassroots organizations emerged in Peru. They were concerned with the problems of local people and poverty reduction. Organizations such as Solaris Peru, Traperos de Emus San Agustin, APRODE PERU, Cáritas del Perú, and the American organization CARE, with their Peruvian location, fought to address poverty in their communities with different approaches, depending on the organization.[citation needed] In 2000, these organizations played an important role in the decentralization process. Their hope was that power would be clearly divided between national and local governments, and the latter would be able to address social justice and the concerns of local people better than the national government could. Some NGO members even became part of local governments. There is a debate about the extent to which this engagement in politics contributes to the attainment of their original goals.[29]

International policy

[edit]Peru or Peruvian organizations participate in the following international organizations:

- Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC)

- Andean Community of Nations (CAN)

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

- Group of Fifteen (G-15)

- Group of Twenty-Four (G-24)

- Group of 77 (G-77)

- Inter-American Development Bank (IADB)

- International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, part of the World Bank Group)

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO)

- International Criminal Court (ICC)

- International Chamber of Commerce (ICC)

- International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU)

- International Red Cross

- International Development Association (IDA)

- International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD)

- International Finance Corporation (IFC)

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRCS)

- International Hydrographic Organization (IHO)

- International Labour Organization (ILO)

- International Monetary Fund, (IMF)

- International Maritime Organization (IMO)

- Interpol

- IOC

- International Organization for Migration (IOM)

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO) (correspondent)

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU)

- Latin American Economic System (LAES)

- Latin American Integration Association (LAIA)

- United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC)

- Non-Aligned Movement (NAM)

- OAS

- Agency for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean (OPANAL)

- Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW)

- Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA)

- Rio Group (RG)

- Union of South American Nations(Unasul-Unasur)

- United Nations

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

- United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

- UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC)

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO)

- United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea (UNMEE)

- United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL)

- Universal Postal Union (UPU)

- World Confederation of Labour (WCL)

- World Customs Organization (WCO)

- World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU)

- World Health Organization (WHO)

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO)

- World Tourism Organization (WToO)

- World Trade Organization (WTrO)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Shugart, Matthew Søberg (September 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive and Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ a b Shugart, Matthew Søberg (December 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive And Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). French Politics. 3 (3): 323–351. doi:10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200087. ISSN 1476-3427. OCLC 6895745903. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

Only in Latin America have all new democracies retained a pure presidential form, except for Peru (president-parliamentary) and Bolivia (assembly-independent).

- ^ Democracy Index 2023: Age of Conflict (PDF). Economist Intelligence Unit (Report). 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-06-09. Retrieved 2024-07-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Gorman, Stephen M. (September 1980). "The Economic and Social Foundations of Elite Power in Peru: A Review of the Literature". Social and Economic Studies. 29 (2/3). University of the West Indies: 292–319.

- ^ a b Vargas, Felipe (November 11, 2020). "Atomización de fuerzas, caudillismos e inestabilidad política: Cómo entender el presente del Congreso de Perú". Emol (in Spanish). Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Chaparro, Amanda (June 2016). "Perú: la derecha o la derecha". Le Monde diplomatique.

- ^ "Peru Congress votes to host OAS summit after outrage over gender neutral bathrooms". Reuters. 2022-07-16. Retrieved 2022-07-16.

- ^ Feline Freier, Luisa; Castillo Jara, Soledad (13 January 2021). ""Terruqueo" and Peru's Fear of the Left". Americas Quarterly. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- ^ "Qué es el "terruqueo" en Perú y cómo influye en la disputa presidencial entre Fujimori y Castillo". BBC News (in Spanish). Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g Levitsky, Steven; Cameron, Maxwell A. (Autumn 2003). "Democracy without Parties? Political Parties and Regime Change in Fujimori's Peru". Latin American Politics and Society. 45 (3): 1–33. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2003.tb00248.x. S2CID 153626617.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Peru's Political Party System and the Promotion of the Pro-Poor Reform" (PDF). National Democratic Institute. March 2005.

- ^ Latin America in the 20th century: 1889-1929, 1991, p. 314-319

- ^ Burt, Jo-Marie (September–October 1998). "Unsettled accounts: militarization and memory in postwar Peru". NACLA Report on the Americas. 32 (2). Taylor & Francis: 35–41. doi:10.1080/10714839.1998.11725657.

the military's growing frustration over the limitations placed upon its counterinsurgency operations by democratic institutions, coupled with the growing inability of civilian politicians to deal with the spiraling economic crisis and the expansion of the Shining Path, prompted a group of military officers to devise a coup plan in the late 1980s. The plan called for the dissolution of Peru's civilian government, military control over the state, and total elimination of armed opposition groups. The plan, developed in a series of documents known as the "Plan Verde," outlined a strategy for carrying out a military coup in which the armed forces would govern for 15 to 20 years and radically restructure state-society relations along neoliberal lines.

- ^ a b Alfredo Schulte-Bockholt (2006). "Chapter 5: Elites, Cocaine, and Power in Colombia and Peru". The politics of organized crime and the organized crime of politics: a study in criminal power. Lexington Books. pp. 114–118. ISBN 978-0-7391-1358-5.

important members of the officer corps, particularly within the army, had been contemplating a military coup and the establishment of an authoritarian regime, or a so-called directed democracy. The project was known as 'Plan Verde', the Green Plan. ... Fujimori essentially adopted the 'Plan Verde,' and the military became a partner in the regime. ... The autogolpe, or self-coup, of April 5, 1992, dissolved the Congress and the country's constitution and allowed for the implementation of the most important components of the 'Plan Verde.'

- ^ Avilés, William (Spring 2009). "Despite Insurgency: Reducing Military Prerogatives in Colombia and Peru". Latin American Politics and Society. 51 (1). Cambridge University Press: 57–85. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2009.00040.x. S2CID 154153310.

- ^ "Peru: Pedro Castillo sworn in as president". Deutsche Welle. 2021-07-28. Retrieved 2022-05-07.

- ^ Aquino, Marco (8 December 2022). "New Peru president sworn in, predecessor Castillo arrested". Reuters.

- ^ "The curious case of Peru's persistent president-to-prison politics". The Week.

- ^ "Peru's presidential lineup: graft probes, suicide and impeachment". Reuters. 15 November 2020.

- ^ Constitución Política del Perú, Article No. 112.

- ^ "In Peru's Presidential Election, the Most Popular Choice Is No One". The New York Times. 12 April 2021. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ a b c "Elecciones Perú 2021: con el 100% del voto procesado, Pedro Castillo y Keiko Fujimori son los candidatos que pasan a la segunda vuelta de las presidenciales" (in Spanish). BBC. 12 April 2021. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ "Conteo rápido de Ipsos al 100%: Pedro Castillo y Keiko Fujimori disputarían segunda vuelta de Elecciones 2021". El Comercio (in Spanish). Peru. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ "Flash electoral a boca de urna región por región, según Ipsos". Diario Correo (in Spanish). 12 April 2021. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ Taj, Mitra; Turkewitz, Julie (20 July 2021). "Pedro Castillo, Leftist Political Outsider, Wins Peru Presidency". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Elections Show Fissures in Peru's Political Institutions". Finch Ratings. 14 April 2021. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Aquino, Marco (26 July 2021). "Peru opposition to lead Congress in setback for socialist Castillo". Reuters. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ a b Asensio, Raúl; Camacho, Gabriela; González, Natalia; Grompone, Romeo; Pajuelo Teves, Ramón; Peña Jimenez, Omayra; Moscoso, Macarena; Vásquez, Yerel; Sosa Villagarcia, Paolo (August 2021). El Profe: Cómo Pedro Castillo se convirtió en presidente del Perú y qué pasará a continuación (in Spanish) (1 ed.). Lima, Peru: Institute of Peruvian Studies. pp. 27–71. ISBN 978-612-326-084-2. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Monika Huber, Wolfgang Kaiser (February 2013). "Mixed Feelings". dandc.eu.