Ovulation

| Ovulation | |

|---|---|

Following a surge of luteinizing hormone (LH), an oocyte (immature egg cell) will be released into the uterine tube, where it will then be available to be fertilized by a male's sperm within 12 hours. Ovulation marks the end of the follicular phase of the ovarian cycle, and the start of the luteal phase. | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D010060 |

| TE | E1.0.0.0.0.0.7 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

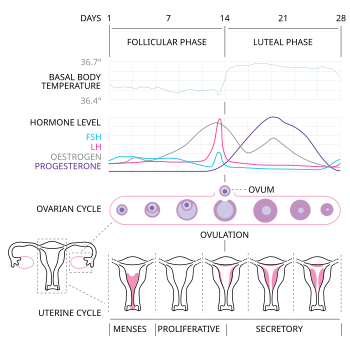

Ovulation is the release of egg cells from the ovaries as part of the ovarian cycle for most vertebrates. In women, this event occurs at the end of the follicular phase, when the ovarian follicles rupture and release the secondary oocyte ovarian cells.[1]

After ovulation, during the luteal phase, the egg will be available to be fertilized by sperm. If it is not, it will break down in less than a day. Meanwhile, the uterine lining (endometrium) continues to thicken to be able to receive a fertilized egg. If no conception occurs, the uterine lining will eventually break down and be shed from the body via the vagina during menstruation.[2]

Process

[edit]

Ovulation occurs about midway through the menstrual cycle, after the follicular phase. The days in which a woman is most fertile can be calculated based on the date of the last menstrual period and the length of a typical menstrual cycle.[3] The few days surrounding ovulation (from approximately days 10 to 18 of a 28-day cycle), constitute the most fertile phase.[4][5][6][7] The time from the beginning of the last menstrual period (LMP) until ovulation is, on average, 14.6[8] days, but with substantial variation among females and between cycles in any single female, with an overall 95% prediction interval of 8.2 to 20.5[8] days.

The process of ovulation is controlled by the hypothalamus of the brain and through the release of hormones secreted in the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).[9] In the preovulatory phase of the menstrual cycle, the ovarian follicle will undergo a series of transformations called cumulus expansion, which is stimulated by FSH. After this is done, a hole called the stigma will form in the follicle, and the secondary oocyte will leave the follicle through this hole. Ovulation is triggered by a spike in the amount of FSH and LH released from the pituitary gland. During the luteal (post-ovulatory) phase, the secondary oocyte will travel through the fallopian tubes toward the uterus. If fertilized by a sperm, the fertilized secondary oocyte or ovum may implant there 6–12 days later.[10]

Follicular phase

[edit]The follicular phase (or proliferative phase) is the phase of the menstrual cycle during which the ovarian follicles mature. The follicular phase lasts from the beginning of menstruation to the start of ovulation.[11][12]

For ovulation to be successful, the ovum must be supported by the corona radiata and cumulus oophorous granulosa cells.[13] The latter undergo a period of proliferation and mucification known as cumulus expansion. Mucification is the secretion of a hyaluronic acid-rich cocktail that disperses and gathers the cumulus cell network in a sticky matrix around the ovum. This network stays with the ovum after ovulation and has been shown to be necessary for fertilization.[14][15]

Ovulation

[edit]Estrogen levels peak towards the end of the follicular phase, around 12 and 24 hours. This, by positive feedback, causes a surge in levels of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). This lasts from 24 to 36 hours, and results in the rupture of the ovarian follicles, causing the oocyte to be released from the ovary.[16]

Through a signal transduction cascade initiated by LH, which activates the pro-inflammatory genes through cAMP secondary messenger, proteolytic enzymes are secreted by the follicle that degrade the follicular tissue at the site of the blister, forming a hole called the stigma. The secondary oocyte leaves the ruptured follicle and moves out into the peritoneal cavity through the stigma, where it is caught by the fimbriae at the end of the fallopian tube. After entering the fallopian tube, the oocyte is pushed along by cilia, beginning its journey toward the uterus.[9]

By this time, the oocyte has completed meiosis I, yielding two cells: the larger secondary oocyte that contains all of the cytoplasmic material and a smaller, inactive first polar body. Meiosis II follows at once but will be arrested in the metaphase and will so remain until fertilization. The spindle apparatus of the second meiotic division appears at the time of ovulation. If no fertilization occurs, the oocyte will degenerate between 12 and 24 hours after ovulation.[17] Approximately 1–2% of ovulations release more than one oocyte. This tendency increases with maternal age. Fertilization of two different oocytes by two different spermatozoa results in fraternal twins.[9]

The precise moment of ovulation was captured on film for the first time in 2008, coincidentally, during a routine hysterectomy procedure. According to the attending gynecologist, the ovum's emergence and subsequent release from the ovarian follicle occurred within a 15-minute timeframe. [18]

Luteal phase

[edit]The follicle proper has met the end of its lifespan. Without the oocyte, the follicle folds inward on itself, transforming into the corpus luteum (pl. corpora lutea), a steroidogenic cluster of cells that produces estrogen and progesterone. These hormones induce the endometrial glands to begin production of the proliferative endometrium and later into secretory endometrium, the site of embryonic growth if implantation occurs. The action of progesterone increases basal body temperature by one-quarter to one-half degree Celsius (one-half to one degree Fahrenheit). The corpus luteum continues this paracrine action for the remainder of the menstrual cycle, maintaining the endometrium, before disintegrating into scar tissue during menses.[19]

Clinical presentation

[edit]The start of ovulation may be detected by signs that are not readily discernible other than to the ovulating female herself, thus humans are said to have a concealed ovulation.[20] In many animal species there are distinctive signals indicating the period when the female is fertile. Several explanations have been proposed to explain concealed ovulation in humans.

Females near ovulation experience changes in the cervical mucus, and in basal body temperature. Furthermore, many females experience secondary fertility signs including Mittelschmerz (pain associated with ovulation) and a heightened sense of smell, and can sense the precise moment of ovulation.[21][22] However, midcycle pain may also not be due to Mittelschmerz, but due to other factors such as cysts, endometriosis, sexually transmitted infections, or an ectopic pregnancy.[23] Other possible signs of ovulation include tender breasts, bloating, and cramps, although these symptoms are not a guarantee that ovulation is taking place.[24][25]

Many females experience heightened sexual desire in the several days immediately before ovulation.[26] One study concluded that females subtly improve their facial attractiveness during ovulation.[27]

Symptoms related to the onset of ovulation, the moment of ovulation and the body's process of beginning and ending the menstrual cycle vary in intensity with each female but are fundamentally the same. The charting of such symptoms — primarily basal body temperature, mittelschmerz and cervical position — is referred to as the sympto-thermal method of fertility awareness, which allow auto-diagnosis by a female of her state of ovulation. Once training has been given by a suitable authority, fertility charts can be completed on a cycle-by-cycle basis to show ovulation. This gives the possibility of using the data to predict fertility for natural contraception and pregnancy planning.

Urine levels of the hormone pregnanediol 3-glucuronide of over 5 μg/mL has been used to confirm ovulation. This test has a 100% specificity over 107 women.[29]

Disorders

[edit]Disorders of ovulation, also known as ovulatory disorders are classified as menstrual disorders and include oligoovulation (infrequent or irregular ovulation) and anovulation (absence of ovulation):[30]

- Oligoovulation is infrequent or irregular ovulation (usually defined as cycles of greater than 36 days or fewer than 8 cycles a year)

- Anovulation is absence of ovulation when it would be normally expected (in a post-menarchal, premenopausal female). Anovulation usually manifests itself as irregularity of menstrual periods, that is, unpredictable variability of intervals, duration, or bleeding. Anovulation can also cause cessation of periods (secondary amenorrhea) or excessive bleeding (dysfunctional uterine bleeding).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed the following classification of ovulatory disorders:[31]

- WHO group I: Hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis failure

- WHO group II: Hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis dysfunction. WHO group II is the most common cause of ovulatory disorders, and the most common causative member is polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).[32]

- WHO group III: Ovarian failure

- WHO group IV: Hyperprolactinemia

Menstrual disorders can often indicate ovulatory disorder.[33]

Ovulation induction

[edit]Ovulation induction is a promising assisted reproductive technology for patients with conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and oligomenorrhea. It is also used in in vitro fertilization to make the follicles mature before egg retrieval. Usually, ovarian stimulation is used in conjunction with ovulation induction to stimulate the formation of multiple oocytes.[34] Some sources[34] include ovulation induction in the definition of ovarian stimulation.

A low dose of human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) may be injected after completed ovarian stimulation. Ovulation will occur between 24 and 36 hours after the HCG injection.[34]

By contrast, induced ovulation in some animal species occurs naturally, ovulation can be stimulated by coitus.[35]

Ovulation suppression

[edit]Combined hormonal contraceptives inhibit follicular development and prevent ovulation as a primary mechanism of action.[36] The ovulation-inhibiting dose (OID) of an estrogen or progestogen refers to the dose required to consistently inhibit ovulation in women.[37] Ovulation inhibition is an antigonadotropic effect and is mediated by inhibition of the secretion of the gonadotropins, LH and FSH, from the pituitary gland.

In assisted reproductive technology including in vitro fertilization, cycles where a transvaginal oocyte retrieval is planned generally necessitates ovulation suppression, because it is not practically feasible to collect oocytes after ovulation. For this purpose, ovulation can be suppressed by either a GnRH agonist or a GnRH antagonist, with different protocols depending on which substance is used.

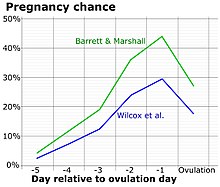

Fertility and timing of ovulation

[edit]Most women who are able to conceive are fertile for an estimated five days before ovulation and one day after ovulation.[38] There is some evidence that for couples who have been trying to conceive a child for less than 12 months, and the female is under 40 years old, practicing timed intercourse (timing intercourse with ovulation using urine tests that predict ovulation) may help improve the rate of pregnancy and live births.[38] The role that stress plays in ovulation, fertility, and understanding the biological basis for stress-induced anovulation and the role of cortisol is not entirely clear.[39]

See also

[edit]- Anovulatory cycle

- Corpus luteum

- Folliculogenesis

- Menstrual cycle

- Oogenesis

- Mittelschmerz

- Fertilisation

Notes

[edit]- ^ Ovulation Test Archived 2016-05-02 at the Wayback Machine at Duke Fertility Center. Retrieved July 2, 2011

- ^ Young B (2006). Wheater's Functional Histology: A Text and Colour Atlas (5th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 359. ISBN 9780443068508. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ^ "How to Chart Your Menstrual Cycle". WebMD. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ Chaudhuri SK (2007). "Natural Methods of Contraception". Practice of Fertility Control: A Comprehensive Manual, 7/e. Elsevier India. p. 49. ISBN 9788131211502. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ^ Allen D (2004). Managing Motherhood, Managing Risk: Fertility and Danger in West Central Tanzania. University of Michigan Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 9780472030279. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ^ Rosenthal M (2012). Human Sexuality: From Cells to Society. Cengage Learning. p. 322. ISBN 9780618755714. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ^ Nichter M, Nichter M (1996). "Cultural Notions of Fertility in South Asia and Their Influence on Sri Lankan Family Planning Practices". In Nichter, Mark, Nichter, Mimi (eds.). Anthropology & International Health: South Asian Case Studies. Psychology Press. pp. 8–11. ISBN 9782884491716. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ^ a b Geirsson RT (May 1991). "Ultrasound instead of last menstrual period as the basis of gestational age assignment". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1 (3): 212–9. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0705.1991.01030212.x. PMID 12797075. S2CID 29063110.

- ^ a b c Marieb E (2013). Anatomy & physiology. Benjamin-Cummings. p. 915. ISBN 9780321887603.

- ^ Wilcox AJ, Baird DD, Weinberg CR (June 1999). "Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 340 (23): 1796–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM199906103402304. PMID 10362823.

- ^ Littleton LA, Engebretson JC (2004-10-14). Maternity Nursing Care. Cengage Learning. p. 195. ISBN 9781401811921. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ^ Gupta RC (2011). Reproductive and Developmental Toxicology. Academic Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780123820334. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ^ "Cumulus Oophorus - an overview". sciencedirect.com. 2012. Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- ^ "Can You Get Pregnant after Ovulation?". coveville.com. 2015-02-03. Retrieved 3 Feb 2015.

- ^ "Fertilization: your pregnancy week by week". medicalnewstoday.com. Retrieved 15 Feb 2016.

- ^ Watson S, Stacy KM (2010). "The Endocrine System". In McDowell J (ed.). Encyclopedia of Human Body Systems. Vol. 1. Greenwood. pp. 201–202. ISBN 9780313391750. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ^ Depares J, Ryder RE, Walker SM, Scanlon MF, Norman CM (June 1986). "Ovarian ultrasonography highlights precision of symptoms of ovulation as markers of ovulation". British Medical Journal. 292 (6535): 1562. doi:10.1136/bmj.292.6535.1562. PMC 1340563. PMID 3087519.

- ^ "Ovulation moment caught on camera". BBC News. 2008-06-12.

- ^ "Usually, it occurs between the 10th and 20th day of your menstrual cycle". momjunction. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ Smith, Yolanda; Pharm, B. (2010-04-27). "Ovulation Signs". News-Medical.net. Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- ^ Navarrete-Palacios E, Hudson R, Reyes-Guerrero G, Guevara-Guzmán R (July 2003). "Lower olfactory threshold during the ovulatory phase of the menstrual cycle". Biological Psychology. 63 (3): 269–79. doi:10.1016/S0301-0511(03)00076-0. PMID 12853171. S2CID 46065468.

- ^ Beckmann, Charles R.B., ed. (2010). Obstetrics and Gynecology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 306–307. ISBN 9780781788076. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ^ "Ovulation Pain: Symptoms, Causes & Pain Relief". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ "Am I Ovulating? How to Spot the Signs". WebMD. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ "Ovulation cramps: Symptoms and what they mean for fertility". www.medicalnewstoday.com. 2020-06-18. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ Bullivant SB, Sellergren SA, Stern K, Spencer NA, Jacob S, Mennella JA, McClintock MK (February 2004). "Women's sexual experience during the menstrual cycle: identification of the sexual phase by noninvasive measurement of luteinizing hormone". Journal of Sex Research. 41 (1): 82–93. doi:10.1080/00224490409552216. PMID 15216427. S2CID 40401379.

- ^ Roberts S, Havlicek J, Flegr J, Hruskova M, Little A, Jones B, Perrett D, Petrie M (August 2004). "Female facial attractiveness increases during the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle". Proc Biol Sci. 271 (Suppl 5:S): 270–2. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0174. PMC 1810066. PMID 15503991.

- ^ Dunson DB, Baird DD, Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR (July 1999). "Day-specific probabilities of clinical pregnancy based on two studies with imperfect measures of ovulation". Human Reproduction. 14 (7): 1835–9. doi:10.1093/humrep/14.7.1835. PMID 10402400.

- ^ Ecochard, R.; Leiva, R.; Bouchard, T.; Boehringer, H.; Direito, A.; Mariani, A.; Fehring, R. (2013-10-01). "Use of urinary pregnanediol 3-glucuronide to confirm ovulation". Steroids. 78 (10): 1035–1040. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2013.06.006. ISSN 0039-128X. PMID 23831784. S2CID 20604171.

- ^ JOYDEV MUKHERJI; RAJENDRA PRASAD GANGULY; SUBRATA LALL SEAL. BASICS OF GYNECOLOGY FOR EXAMINEES: ALL IN ONE : THEORY, CLINICS & CASE DISCUSSION, INSTRUMENTS AND SPECIMENS, OPERATIVE GYNECOLOGY AND RADIOLOGY (X-RAY, USG INCLUDING 3D). Academic Publishers. pp. 244–. ISBN 9789387162303.

- ^ Page 54 in: McVeigh E, Guillebaud J, Homburg R (2008). Oxford handbook of reproductive medicine and family planning. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-920380-2.

- ^ Baird, D. T.; Balen, A.; Escobar-Morreale, H. F.; Evers, J. L. H.; Fauser, B. C. J. M.; Franks, S.; Glasier, A.; Homburg, R.; La Vecchia, C.; Devroey, P.; Diedrich, K.; Fraser, L.; Gianaroli, L.; Liebaers, I.; Sunde, A.; Tapanainen, J. S.; Tarlatzis, B.; Van Steirteghem, A.; Veiga, A.; Crosignani, P. G.; Evers, J. L. H. (2012). "Health and fertility in World Health Organization group 2 anovulatory women". Human Reproduction Update. 18 (5): 586–99. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms019. PMID 22611175.

- ^ Emre Seli, ed. (2 February 2011). Infertility. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-9394-1. OCLC 1083163793.

- ^ a b c IVF.com > Ovulation Induction Archived 2012-02-26 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on Mars 7, 2010

- ^ Bakker J, Baum MJ (July 2000). "Neuroendocrine regulation of GnRH release in induced ovulators". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 21 (3): 220–62. doi:10.1006/frne.2000.0198. hdl:2268/91368. PMID 10882541. S2CID 873489.

- ^ Nelson AL, Cwiak C (2011). "Combined oral contraceptives (COCs)". In Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates W, Kowal D, Policar MS (eds.). Contraceptive technology (20th revised ed.). New York: Ardent Media. pp. 249–341. ISBN 978-1-59708-004-0. ISSN 0091-9721. OCLC 781956734. pp. 257–258

- ^ Endrikat J, Gerlinger C, Richard S, Rosenbaum P, Düsterberg B (December 2011). "Ovulation inhibition doses of progestins: a systematic review of the available literature and of marketed preparations worldwide". Contraception. 84 (6): 549–57. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.04.009. PMID 22078182.

- ^ a b Gibbons, Tatjana; Reavey, Jane; Georgiou, Ektoras X; Becker, Christian M (2023-09-15). Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group (ed.). "Timed intercourse for couples trying to conceive". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (9): CD011345. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011345.pub3. PMC 10501857. PMID 37709293.

- ^ Karunyam, Bheena Vyshali; Abdul Karim, Abdul Kadir; Naina Mohamed, Isa; Ugusman, Azizah; Mohamed, Wael M. Y.; Faizal, Ahmad Mohd; Abu, Muhammad Azrai; Kumar, Jaya (2023). "Infertility and cortisol: a systematic review". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 14: 1147306. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1147306. ISSN 1664-2392. PMC 10344356. PMID 37455908.

Further reading

[edit]- Baerwald AR, Adams GP, Pierson RA (July 2003). "A new model for ovarian follicular development during the human menstrual cycle". Fertility and Sterility. 80 (1): 116–22. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(03)00544-2. PMID 12849812.

- Chabbert Buffet N, Djakoure C, Maitre SC, Bouchard P (July 1998). "Regulation of the human menstrual cycle". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 19 (3): 151–86. doi:10.1006/frne.1998.0167. PMID 9665835. S2CID 40594356.

- Fortune JE (February 1994). "Ovarian follicular growth and development in mammals". Biology of Reproduction. 50 (2): 225–32. doi:10.1095/biolreprod50.2.225. PMID 8142540.

- Guraya SS, Dhanju CK (November 1992). "Mechanism of ovulation--an overview". Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 30 (11): 958–67. PMID 1293040.

- Klowden MJ (2009). "Oviposition Behavior". In Resh VH, Carde RT (eds.). Encyclopedia of Insects. Academic Press. ISBN 9780080920900. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- Su HW, Yi YC, Wei TY, Chang TC, Cheng CM (September 2017). "Detection of ovulation, a review of currently available methods". Bioengineering & Translational Medicine. 2 (3): 238–246. doi:10.1002/btm2.10058. PMC 5689497. PMID 29313033.