China–Vietnam relations

| |

China |

Vietnam |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Chinese Embassy, Hanoi | Vietnamese Embassy, Beijing |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador He Wei | Ambassador Pham Sao Mai |

Relations between Vietnam and China (Chinese: 中越关系, pinyin: Zhōng-Yuè Guān Xì; Vietnamese: Quan hệ Việt–Trung) had been extensive for a couple of millennia, with Northern Vietnam especially under heavy Sinosphere influence during historical times. Despite their Sinospheric and socialist background, centuries of conquest by modern China's imperial predecessor as well as modern-day tensions have made relations wary.[1][2] The People's Republic of China (PRC) ruled by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) assisted North Vietnam and the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) during the Vietnam War whilst the Taiwan-based Republic of China (ROC) was allied with South Vietnam.

Following the fall of Saigon in 1975 and the subsequent Vietnamese reunification in 1976, relations between the two countries started to deteriorate. Vietnam ousted the Khmer Rouge, a party that China propped up which had become genocidal, from power in Cambodia. China invaded Vietnam in 1979, beginning the Sino-Vietnamese War. China perceived Vietnam's domination over Indochina from Vietnam's historical legacy (Minh Mang) whilst Vietnam desired Vietnamese-friendly neighbors (Laos and Cambodia) bordering its immediate western borders.

Cross-border raids and skirmishes ensued, in which China and Vietnam fought a prolonged border war from 1979 to 1990. The two countries officially normalized diplomatic ties in 1991. Although both sides have since worked to improve their diplomatic and economic ties, the two countries remain in dispute over political and territorial issues in the South China Sea (or East Sea).[3] China and Vietnam share a 1,281 kilometres (796 miles) border. However, the two countries have been striving for restraint as well as present and future stability.[4][5] The two countries' political parties, although faced with a number of concerns, have since maintained ideological ties.[6]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

China and Vietnam had contact since the Chinese Warring States period and the Vietnamese Thục dynasty in the 3rd century BC (disputed), as noted in the 15th-century Vietnamese historical record Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư. Between the 1st century BC and the 15th century AD, Vietnam was subject to four separate periods of imperial Chinese domination although it successfully asserted a degree of independence after the Battle of Bạch Đằng in 938 AD.

According to the old Vietnamese historical records Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư and Khâm Định Việt Sử Thông Giám Cương Mục, An Dương Vương (Thục Phán) was a prince of the Chinese state of Shu (蜀, which shares the same Chinese character as his surname Thục),[7]: 19 sent by his father first to explore what are now the southern Chinese provinces of Guangxi and Yunnan and then to move their people to what is now northern Vietnam during the invasion of the Qin dynasty.[citation needed]

Some modern Vietnamese scholars[who?] believe that Thục Phán came upon Âu Việt, which is now northernmost Vietnam, western Guangdong, and southern Guangxi Province, with its capital in what is today Cao Bằng Province).[8] After assembling an army, he defeated Hùng Vương XVIII, the last ruler of the Hồng Bàng dynasty, in 258 BC. He proclaimed himself An Dương Vương ("King An Dương"), renamed his newly acquired state from Văn Lang to Âu Lạc and established the new capital at Phong Khê (now Phú Thọ, a town in northern Vietnam), where he tried to build Cổ Loa Citadel, the spiral fortress approximately ten miles north of his new capital.[citation needed]

Han Chinese migration into Vietnam has been dated back to the era of the 2nd century BC, when Qin Shi Huang first placed northern Vietnam under Chinese rule (disputed), Chinese soldiers and fugitives from Central China have migrated en masse into northern Vietnam since then and introduced Chinese influences into Vietnamese culture.[9][10] The Chinese military leader Zhao Tuo founded the Triệu dynasty, which ruled Nanyue in southern China and northern Vietnam. The Qin governor of Canton advised Zhao to found his own independent kingdom since the area was remote, and there were many Chinese settlers in the area.[7]: 23 The Chinese prefect of Jiaozhi, Shi Xie, ruled Vietnam as an autonomous warlord and was posthumously deified by later Vietnamese emperors. Shi Xie was the leader of the elite ruling class of Han Chinese families that immigrated to Vietnam and played a major role in developing Vietnam's culture.[7]: 70

Imperial period

[edit]

Vietnam emerged from the disintegration of China's Tang dynasty in the early 900s.[11]: 49 The border between China and Vietnam was generally stable for the next 800 years, with China challenging the border once.[11]: 49

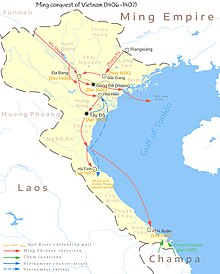

China invested the Trần dynasty (1225-1400) as Vietnam's rulers.[11]: 50 The Trần's control of Vietnam weakened in the 1390s and in 1400, Hồ Quý Ly deposed the Trần ruler and declared himself the founder of a new dynasty.[11]: 50 The Trần requested that China's Ming dynasty intervene on its behalf.[11]: 50 The Ming sent troops and envoy to re-establish the Trần and quickly defeated Hồ.[11]: 50 The Ming subsequently deemed the Trần to be in disarray and instead reclaimed Vietnam as its own territory.[11]: 50 Subsequent Ming emperors returned the relationship to a tributary with a Vietnamese ruler in Vietnam.[11]: 50

According to a 2018 study in the Journal of Conflict Resolution on Vietnam-China relations from 1365 to 1841, they could be characterized as a "hierarchic tributary system" from 1365 to 1841.[12] During Vietnam's Đại Việt period (968-1804), the Vietnamese court explicitly recognized its unequal status compared to China through explicit institutional mechanisms.[12][11]: 55 Vietnam conducted its relations with China through the tributary system.[11]: 55 During this period, Vietnam was primarily focused on addressing its domestic instability and its external relations generally focused to the south and west,[12] including with the Champa kingdom, among others.[11]: 55

In 1884, during Vietnam's Nguyễn dynasty, the Qing dynasty and France fought the Sino-French War, which ended in a Chinese defeat. The Treaty of Tientsin recognized French dominance in Vietnam and Indochina, spelling the end of formal Chinese influence on Vietnam and the beginning of Vietnam's French colonial period.

Both China and Vietnam faced invasion and occupation by Imperial Japan during World War II, and Vietnam languished under the rule of Vichy France. In the Chinese provinces of Guangxi and Guangdong, Vietnamese revolutionaries, led by Phan Bội Châu, had arranged alliances with the Chinese Nationalists, the Kuomintang, before the war by marrying Vietnamese women to Chinese National Revolutionary Army officers. Their children were at an advantage since they could speak both languages and so they worked as agents for the revolutionaries, spreading their ideologies across borders. The intermarriage between Chinese and Vietnamese was viewed with alarm by the French. Chinese merchants also married Vietnamese women and provided funds and help for revolutionary agents.[13]

Late in the war, with Japan and Nazi Germany nearing defeat, US President Franklin Roosevelt privately decided that the French should not return in Indochina after the war was over. Roosevelt offered the Kuomintang leader, Chiang Kai-shek, all of Indochina to be under Chinese rule, but Chiang Kai-shek reportedly replied, "Under no circumstances!"[14] In August 1943, China broke diplomatic relations with Vichy France, with the Central Daily News announcing that diplomatic relations were to be solely between the Chinese and the Vietnamese, with no French intermediary. China had planned to spread massive propaganda on the Atlantic Charter and Roosevelt's statement on Vietnamese self-determination to undermine the French authority in Indochina.[15]

Cold War

[edit]

After the Second World War ended, a United Nations mandate, had 200,000 Chinese troops, led by General Lu Han, sent by Chiang Kai-shek to Indochina north of the 16th parallel with the aim of accepting the surrender of the Japanese occupying forces. The troops remained in Indochina until 1946.[16] The Chinese used the Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng, the Vietnamese version of the Chinese Kuomintang, to increase their influence in Indochina and to put pressure on their opponents.[17] Nevertheless, the Chinese occupation forces allowed Ho Chi Minh's Democratic Republic of Vietnam more influence than the British Army occupation authorities in the south.[18] Chiang Kai-shek threatened the French with war to force them to negotiate with Ho Chi Minh. In February 1946, Chiang forced the French colonists to surrender all of their concessions in China and to renounce their extraterritorial privileges in exchange for withdrawing from northern Indochina and for allowing French troops to reoccupy the region.[19][20][21][22]

China |

North Vietnam |

|---|---|

Vietnam War

[edit]Republic of China |

South Vietnam |

|---|---|

Along with the Soviet Union, China was an important strategic ally of North Vietnam during the Indochina Wars. The Chinese Communist Party provided arms, military training and essential supplies to help the communist North defeat the imperialist French colonial empire, capitalist South Vietnam, their ally the United States, and other anti-communists between 1949 and 1975.[23] During Mao's December 1949 visit to the Soviet Union, Stalin sought Mao's assistance in supporting the Vietnamese Communists against France in the First Indochina War.[24]: 65 Mao accepted Stalin's view of a "worldwide communist revolution" and agreed to share "the international responsibility" and support the Vietnamese communists.[24]: 65 After Mao's return to China, the country began sending military advisors and military aid to the Vietnamese.[24]: 66

During 1964 to 1969, China reportedly sent over 300,000 troops, mostly in anti-aircraft divisions to combat in Vietnam.[25] However, the Vietnamese communists remained suspicious of China's perceived attempts to increase its influence over Vietnam.[26]

During the 1954 Geneva Conference ending the First Indochina War, Chinese premier Zhou Enlai urged the Viet Minh delegation to accept partition at the 17th parallel, which was regarded as a betrayal.[27]

In 1960, China became the first country to recognize the Viet Cong in Vietnam.[citation needed] Ho Chi Minh and Mao Zedong frequently characterized the bilateral relationship as "comrade plus brother".[28]: 96–97 In 1963, Liu Shaoqi praised the strength of the relationship, stating, "Our friendship has a long history. It is a militant friendship, forged in the storm of revolution, a great class friendship that is proletarian internationalist in character, a friendship that is indestructible."[28]: 97

Vietnam was an ideological battleground during the 1960s Sino-Soviet split. After the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident, Chinese premier Deng Xiaoping secretly promised the North Vietnamese 1 billion yuan in military and economic aid if they refused all Soviet aid.

In response to U.S. bombing of North Vietnam, China launched the Resist America, Aid Vietnam campaign.[29]: 29 The campaign themes denounced U.S. imperialism and promoted Vietnamese resistance.[29]: 29 Local communist party cadre organized mass meetings and street demonstrations, and millions of people across the country marched in China to support the campaign between February 9 and February 11, 1965.[29]: 29 The communist party also expanded the campaign into cultural media such as film and photography exhibitions, singing contests, and street performances.[29]: 29

During the Vietnam War, the North Vietnamese and the Chinese had agreed to defer tackling their territorial issues until South Vietnam was defeated. Those issues included the lack of delineation of Vietnam's territorial waters in the Gulf of Tonkin and the question of sovereignty over the Paracel and Spratly Islands in the South China Sea.[26] During the 1950s, half of the Paracels were controlled by China and the rest by South Vietnam. In 1958, North Vietnam accepted China's claim to the Paracels and relinquished its own claim;[30] one year earlier, China had ceded White Dragon Tail Island to North Vietnam.[31] The potential of offshore oil deposits in the Gulf of Tonkin heightened tensions between China and South Vietnam.[citation needed]

Vietnam disapproved of China's efforts to improve relations with the United States.[28]: 93 Prime Minister Phạm Văn Đồng asked Mao Zedong to cancel the 1972 visit of United States President Richard Nixon to China, but Mao declined.[28]: 93

In 1973, with the Vietnam War drawing to a close, North Vietnam announced its intention to allow foreign companies to explore oil deposits in disputed waters. In January 1974, a clash between Chinese and South Vietnamese forces resulted in China taking complete control of the Paracels.[26] After its Fall of Saigon in 1975, North Vietnam took over the South Vietnamese-controlled portions of the Spratly Islands.[26] The unified Vietnam then canceled its earlier renunciation of its claim to the Paracels, and both China and Vietnam claim control over all the Spratlys and actually control some of the islands.[30]

1970s

[edit]By the mid-1970s, the relationship between China and Vietnam was strained.[28]: 93 The tensions between the two countries developed in relation to a number of issues, including Vietnam's support of the Soviet side during the Sino-Soviet split, Vietnam's invasion of Cambodia, Vietnam's mistreatment of ethnic Chinese in Vietnam, and border conflicts.[28]: 43

Tensions were heightened in the 1970s by the Vietnamese government's oppression of the Hoa minority (Vietnamese of Chinese ethnicity[26][32]). In February 1976, Vietnam implemented registration programs in the south.[28]: 94 Ethnic Chinese in Vietnam were required to adopt Vietnamese citizenship or leave the country.[28]: 94 In early 1977, Vietnam implemented what it described as a purification policy in its border areas to keep Chinese border residents to the Chinese side of the border.[28]: 94–95 Following another discriminatory policy introduced in March 1978, a large number of Chinese fled from Vietnam to southern China.[28]: 95 China and Vietnam attempted to negotiate issues related to Vietnam's treatment of ethnic Chinese, but these negotiations failed to resolve the issues.[28]: 95

China's support of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia concerned Vietnamese leadership, which feared encirclement by China.[28]: 94 The 1977 Cambodian–Vietnamese War caused tensions with China, which had allied itself with Democratic Kampuchea.[26][32]

In June 1978, China rescinded the appointment of its consul general to Ho Chi Minh City and informed Vietnam that it must close three of its consulates in China.[28]: 96 By the end of July 1978, China ended all of its aid programs to Vietnam and recalled all of its experts from Vietnam.[28]: 96

Sino-Vietnamese conflicts 1979–1990

[edit]Vietnam had signed a treaty of friendship with the Soviet Union and established extensive commercial and military ties.[26][32]

On February 17, 1979, the Chinese People's Liberation Army crossed the Vietnamese border but withdrew on March 5, after a two-week campaign had devastated northern Vietnam and briefly threatened the Vietnamese capital, Hanoi.[26] Both sides suffered relatively heavy losses, with thousands of casualties. Subsequent peace talks broke down in December 1979, and China and Vietnam began a major buildup of forces along the border. Vietnam fortified its border towns and districts and stationed as many as 600,000 troops. China stationed 400,000 troops on its side of the border.[citation needed] Sporadic fighting on the border occurred throughout the 1980s, and China threatened to launch another attack to force Vietnam's exit from Cambodia.[26]

1990–present

[edit]

With the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union and Vietnam's 1990 exit from Cambodia, China–Vietnam ties began to improve. Both nations planned the normalization of their relations in a secret summit in Chengdu in September 1990, and officially normalized ties on 5 November 1991.[32][33] Since 1991, the leaders and high-ranking officials of both nations have exchanged visits. China and Vietnam both recognized and supported the post-1991 government of Cambodia, and supported each other's bid to join the World Trade Organization (WTO).[32] In 1999, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam, Le Kha Phieu, visited Beijing, where he met General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Jiang Zemin and announced a joint 16 Word Guideline for improved bilateral relations; a Joint Statement for Comprehensive Cooperation was issued in 2000.[32] In 2000, Vietnam and China successfully resolved longstanding disputes over their land border and maritime rights in the Gulf of Tonkin, including the cession of land surrounding the Friendship Pass to China.[23][32][34] A joint agreement between China and ASEAN in 2002 marked out a process of peaceful resolution and guarantees against armed conflict.[32] In 2002, Jiang Zemin made an official visit to Vietnam in which numerous agreements were signed to expand trade and co-operation and to resolve outstanding disputes.[23]

Vietnam and China signed a protocol on science and technology cooperation in 2009.[35]: 158

In November 2009, Vietnam and China signed a land boundary demarcation agreement on their land borders.[35]: 158 On 1 December 2015, the two countries signed an agreement to resolve border marker problems and to enhance cooperation in protecting and managing border markers.[35]: 167

In 2020, for the celebration of Vietnam's 75th National Day, CCP general secretary Xi Jinping and CPV general secretary Nguyễn Phú Trọng reaffirmed their bilateral ties while looking back saying: "In the past 70 years, although there have been some ups and downs in bilateral relations, friendship and cooperation had always been the main flow."[36] Nguyễn Phú Trọng visited China in 2022 where he met Xi, becoming the first foreign leader to meet Xi after he secured a third term in the 20th CCP National Congress.[37] Both leaders released a joint statement, calling for cooperation in economic, political, defense and security areas and working together in “the fight against terrorism, ‘peaceful evolution’, ‘colour revolution’ and the politicisation of human rights issues”.[37] Vietnamese prime minister Phạm Minh Chính visited China in June 2023 to attend a summit of the World Economic Forum. While in China, he met with Xi, Chinese premier Li Qiang,[38] chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress Zhao Leji,[39] and chairman of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference Wang Huning.[40] Phạm additionally visited Xiong'an New Area, a key project of Xi.

On August 19, 2024, Wang Huning, a high-ranking CPC official, and To Lam, the President of Vietnam, met in Beijing. They discussed the strategic plans established by their leaders to enhance the China-Vietnam relationship and promote their shared future. Both parties reaffirmed their commitment to advancing cooperation between their countries. The meeting also included Hu Chunhua and Wang Dongfeng.[41]

On 13 October 2024, Vietnam and China signed 10 agreements to boost cross-border rail links, payment systems, and economic cooperation, while also enhancing defense and trade relations.[42]

Commercial ties

[edit]

As of at least 2024, the Vietnamese economy is becoming increasingly connected with China's.[43]: 102 Vietnam is China's eighth largest trading partner, and largest among southeast Asian countries.[43]: 102

As of 2022, China's accounted for 15.5% of the total exports values of Vietnam and 32.9% of imports of Vietnam.[44]

After both sides resumed trade links in 1991, growth in annual bilateral trade increased from only US$32 million in 1991 to almost US$7.2 billion in 2004.[45] By 2011, the trade volume had reached US$25 billion.[46] In 2019, the total value of trade between the two countries amounted to US$517 billion.[47]

Vietnam's exports to China include crude oil, coal, coffee, and food, and China exports pharmaceuticals, machinery, petroleum, fertilizers, and automobile parts to Vietnam. Both nations are working to establish an "economic corridor" from China's Yunnan Province to Vietnam's northern provinces and cities and similar economic zones linking China's Guangxi Province with Vietnam's Lạng Sơn and Quang Ninh Provinces, and the cities of Hanoi and Haiphong.[45] Air and sea links and a railway line have been opened between the countries, along with national-level seaports in the frontier provinces and regions of the two countries.[23] Joint ventures have furthermore been launched, such as the Thai Nguyen Steel Complex,[45] but the deal eventually fell through, resulting in the bankruptcy of state-owned Thai Nguyen Iron and Steel VSC and the withdrawal of the China Metallurgical Group Corporation from the project.[48]

Chinese investments in Vietnam have been rising since 2015, reaching US$2.17 billion in 2017.[49] With the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership, Vietnam was anticipated to offer more access to regional markets for Chinese affiliated firms.[50]

In 2018, protesters went on the streets in Vietnam against government plans to open new special economic zones, including one in Quang Ninh, near the Chinese border, which would allow 99-year land leases, citing concerns about Chinese dominance.[51][52]

Vietnam became able to export fresh durian to China in 2022.[53]

Territory issues

[edit]

The land border of China and Vietnam is 1,347 kilometers.[28]: 95 Two Chinese provinces adjoin the border, and seven Vietnamese provinces do.[28]: 94–95

Border disputes between the two countries were significant in the 1970s.[28]: 95 One hundred sixty-four locations on the land border totaling 227 square kilometers were disputed.[28]: 95 Because there was not yet clear border demarcation, the countries engaged in a pattern of retaliatory land grabs and violence.[28]: 95 The number of border skirmishes increased yearly from 125 in 1974 to 2,175 in 1978.[28]: 95

The two countries attempted a first round of negotiations to resolve land border issues, but were not successful.[28]: 95 A second round of negotiations in August 1978 was also unsuccessful because of the Youyi Pass Incident in which the Vietnamese army and police expelled 2,500 refugees across the order into China.[28]: 95 Vietnamese authorities beat and stabbed refugees during the incident, as well as 9 Chinese civilian border workers.[28]: 95 Following this event, Vietnam occupied the Pu Nian Ling area, which Chian also claimed.[28]: 95

In June 2011, Vietnam announced that its military would conduct new exercises in the South China Sea. China had previously voiced its disagreement over Vietnamese oil exploration in the area, stating that the Spratly Islands and the surrounding waters were its sovereign territory.[54] Defense of the South China Sea was cited as one of the possible missions of the first Chinese PLA Navy aircraft carrier, the Liaoning, which entered service in September 2012.[55]

In October 2011, Nguyễn Phú Trọng, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam, made an official visit to China at the invitation of General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Hu Jintao with the aim of improving relations in the wake of the border disputes.[46] However, on 21 June 2012, Vietnam passed a law entitled the "Law on the Sea", which placed both the Spratly Islands and the Paracel Islands under Vietnamese jurisdiction, prompting China to label the move as "illegal and invalid."[56][28]: 228 A month afterwards, China enacted a previously delayed plan established prefecture of Sansha City,[28]: 228 which encompassed the Xisha (Paracel), Zhongsha, and Nansha (Spratly) Islands and the surrounding waters.[57] Vietnam proceeded to a strong opposition to the measure and the reaffirmation of its sovereignty over the islands. Other countries surrounding the South China Sea have claims to the two island chains, including Taiwan, Brunei, Malaysia, and the Philippines.[56][58]

On October 19, 2020, Japanese prime minister Yoshihide Suga visited his Vietnamese counterpart Nguyễn Xuân Phúc,[59] and they agreed to cooperate on regional issues including the South China Sea, where China's growing assertiveness in disputed waters has drawn serious concern.[60] Following Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi's high-profile visit to Vietnam in September 2021, where the Chinese foreign minister had avoided Vietnam for three years, Japanese defense minister Nobuo Kishi shortly followed up with his first visit overseas ever after Wang Yi's visit. Nobuo Kishi signed an accord that Japanese-made defense equipment and technology are to be exported to the Southeast Asian country, and to boost cooperation amid worries of China's actions.[61]

2013–2015 fishing and oil standoffs

[edit]

In May 2013 Vietnam accused China of hitting one of its fishing boats.[62]

On 7 June 2013, the two countries established a naval hotline.[35]: 162 On 21 June 2013, Vietnam and China established a hot line to deal with fisheries incidents.[35]: 162

In May 2014, Vietnam accused China of ramming and sinking a fishing boat.[63] In recent years, Beijing oversaw the replacement of traditional Chinese wooden fishing vessels with steel-hulled trawlers, fitted with modern communication and high-tech navigation systems. The better-equipped boats sailed into the disputed waters as a state-subsidized operation to extend Chinese sovereignty, while in Vietnam, private citizens, not the government, would donate to Vietnamese fishermen to maintain their position in the South China Sea and to defend national sovereignty.[64] That dynamic continues to be a major source of tension between the two countries.[citation needed]

In May 2014, both countries sparred over an oil rig in disputed territory in the South China Sea, which triggered deadly anti-Chinese protests in Vietnam.[65] Rioters attacked hundreds of foreign-owned factories in an industrial park in southern Vietnam, targeting Chinese ones.[66] Following the damage, the Vietnamese government pursued a more moderate foreign policy approach with China and sought to improve the bilateral relations.[28]: 3

In June China declared there would be no military conflict with Vietnam.[65] China then had 71 ships in the disputed area, and Vietnam had 61.[67]

However, on 2 June 2014, it was reported by VGP News, the online newspaper of the Vietnamese Government that the previous day, Chinese ships had in three waves attacked two Vietnam Coast Guard ships, a Vietnamese fisheries surveillance ship and a number of other ships by physically ramming the ships and with water cannons.[68]

In 2014, a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center showed 84% of Vietnamese were concerned that disputes relating to the South China Sea could lead to military conflict.[69]

In 2017, Beijing warned Hanoi that it would attack Vietnamese bases in the Spratly Islands if gas drilling continued in the area. Hanoi then ordered Spain's Repsol, whose subsidiary was conducting the drilling, to stop drilling.[70][71]

2019–present

[edit]Through 2019 and 2020, Chinese ships have continued attacking and sinking of Vietnamese fishing and other vessels in different incidents.[72] Vietnam only reacted to these incidents by official statements and diplomatic protests.[73] In late 2020, Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe met with Vietnamese ambassador to China Phạm Sao Mai in an attempt to cool down tensions after an increased number of incidents.[74] The Vietnamese strategy on the South Chinese Sea disputes has been described as a long term consistent act of "balancing, international integration and 'cooperation and struggle'."[75]

In 2020, Bloomberg News reported that a hacker group known as APT32 or OceanLotus, allegedly affiliated with the Vietnamese government, targeted China's Ministry of Emergency Management and the Wuhan municipal government in order to obtain information about the COVID-19 pandemic. The Vietnamese Ministry of Foreign Affairs called the accusations unfounded.[76][77][78]

Illegal border crossings by Chinese nationals was linked by the Vietnamese public as the perceived cause of new COVID-19 infections in Vietnam, although there had been no evidence for this.[79][80]

In May 2020, an Israeli cybersecurity company reported to have discovered ransomware attacks targeting government systems in Vietnam and several other countries by China-linked groups.[81]

In August 2021 shortly before an expected visit by US Vice President Kamala Harris, Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh reassured Xiong Bo, the Chinese envoy to Hanoi that Vietnam will not enter an alliance to counter China.[82] Pham suggested the two nations should join with ASEAN to expedite "the slow-moving negotiations" and achieve a code of conduct in the disputed South China Sea region and that his country wanted to build political trust, cooperation and promote exchange with China. Xiong stated in the meeting that the two communist nations shared the same political system and beliefs and that China was willing to work with Vietnam and stick to the two countries’ high-level strategic directive to further develop ties. Xiong also requested for Vietnam's support in opposing what China claims as “politicisation” of COVID-19 origin investigations.[83]

In March 2023, Chinese and Vietnamese vessels had chased each other in South China Sea in an incident where Chinese ship intruded into Vietnam's Special Economic Zone.[84]

On December 12, 2023, the two countries announced 36 cooperation agreements during a visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping to Vietnam.[85] The agreements addressed a variety of issues, including cross-border rail development, digital infrastructure, and establishing joint patrols in the Gulf of Tonkin and a hotline to handle South China Sea fishing incidents.[85] China and Vietnam also issued a joint statement to support building a community of shared future for humankind.[85] In September 2024, Vietnamese media reported that Chinese personnel boarded a Vietnamese fishing vessel near the Parcel Islands and beat its crew with iron bars.[86] Vietnam and the Philippines condemned the attack while China disputed Vietnam's version of the incident.[87]

Diplomatic missions

[edit]

|

|

See also

[edit]- List of ambassadors of China to Vietnam

- List of ambassadors of Vietnam to China

- History of China

- History of Vietnam

- Sinicization

- Anti-Chinese sentiments

- Anti-Vietnamese sentiments

- Sino-Vietnamese Wars

- China–Vietnam border

- United States–Vietnam relations

- Vietnam–European Union relations

- Russia–Vietnam relations

References

[edit]- ^ Forbes, Andrew. "Why Vietnam Loves and Hates China". Asia Times. 26 April 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "China: The Country to the North". Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David (2012). Vietnam Past and Present: The North. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B006DCCM9Q.

- ^ "Q&A: South China Sea dispute". BBC. 22 January 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "China, Vietnam should avoid magnifying S. China Sea disputes - China's Wang Yi". Reuters. 11 September 2021.

- ^ "China to maintain healthy, stable, comprehensive development of ties with Vietnam, says Wang Yi". The Star. Retrieved 2021-09-12.

- ^ VietnamPlus (2021-09-28). "Vietnam, China share experience in Party building | Politics | Vietnam+ (VietnamPlus)". VietnamPlus. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ a b c Taylor, K.W. (1991). The Birth of Vietnam. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520074170. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ Chapuis, O. (1995). A History of Vietnam: From Hong Bang to Tu Duc. Greenwood Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780313296222. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ Long Le (February 8, 2008). "Chinese Colonial Diasporas (207 B.C.-939 A.D.)". University of Houston Bauer The Global Viet. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ Long Le (January 30, 2008). "Colonial Diasporas & Traditional Vietnamese Society". University of Houston Bauer The Global Viet. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ma, Xinru; Kang, David C. (2024). Beyond Power Transitions: The Lessons of East Asian History and the Future of U.S.-China Relations. Columbia Studies in International Order and Politics. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-55597-5.

- ^ a b c Kang, David C.; Nguyen, Dat X.; Fu, Ronan Tse-min; Shaw, Meredith (2019). "War, Rebellion, and Intervention under Hierarchy: Vietnam–China Relations, 1365 to 1841". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 63 (4): 896–922. doi:10.1177/0022002718772345. S2CID 158733115.

- ^ Christopher E. Goscha (1999). Thailand and the Southeast Asian networks of the Vietnamese revolution, 1885-1954. Psychology Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-7007-0622-4.

- ^ Barbara Wertheim Tuchman (1985). The march of folly: from Troy to Vietnam. Random House, Inc. p. 235. ISBN 0-345-30823-9.

- ^ Liu, Xiaoyuan (2010). "Recast China's Role in Vietnam". Recast All Under Heaven: Revolution, War, Diplomacy, and Frontier China in the 20th Century. Continuum. pp. 66, 69, 74, 78.

- ^ Larry H. Addington (2000). America's war in Vietnam: a short narrative history. Indiana University Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-253-21360-6.

- ^ Peter Neville (2007). Britain in Vietnam: prelude to disaster, 1945-6. Psychology Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-415-35848-4.

- ^ Bradley, Mark Philip (2010-12-31), Anderson, David L. (ed.), "1. Setting the Stage: Vietnamese Revolutionary Nationalism and the First Vietnam War", The Columbia History of the Vietnam War, Columbia University Press, pp. 93–119, doi:10.7312/ande13480-003, ISBN 978-0-231-13480-4, retrieved 2021-11-09

- ^ Van Nguyen Duong (2008). The tragedy of the Vietnam War: a South Vietnamese officer's analysis. McFarland. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7864-3285-1.

- ^ Stein Tønnesson (2010). Vietnam 1946: how the war began. University of California Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-520-25602-6.

- ^ Elizabeth Jane Errington (1990). The Vietnam War as history: edited by Elizabeth Jane Errington and B.J.C. McKercher. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 63. ISBN 0-275-93560-4.

- ^ "The Vietnam War: Seeds of Conflict 1945–1960". The History Place. 1999. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d "China-Vietnam Bilateral Relations". Sina.com. 28 August 2005. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- ^ a b c Li, Xiaobing (2018). The Cold War in East Asia. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-65179-1.

- ^ "CHINA ADMITS COMBAT IN VIETNAM WAR". Washington Post. 17 May 1989. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Vietnam - China". U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- ^ Hastings, Max (2018). Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy 1945-1975. New York. ISBN 978-0-06-240566-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Wang, Frances Yaping (2024). The Art of State Persuasion: China's Strategic Use of Media in Interstate Disputes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197757512.

- ^ a b c d Minami, Kazushi (2024). People's Diplomacy: How Americans and Chinese Transformed US-China Relations during the Cold War. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501774157.

- ^ a b Cole, Bernard D (2012). The Great Wall at Sea: China's Navy in the Twenty-First Century (2 ed.). Naval Institute Press. p. 27.

- ^ Frivel, M. Taylor. "Offshore Island Disputes". Strong Borders, Secure Nation: Cooperation and Conflict in China's Territorial Disputes. Princeton University Press. pp. 267–299.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Womack, Brantly (2006). China and Vietnam: Politics of Asymmetry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–28. ISBN 0-521-85320-6.

- ^ https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1991/11/06/china-and-vietnam-normalize-relations/8b90e568-cb51-44a3-9a84-90a515e29129/

- ^ "In Westminster, an Internet Bid to Restore Viet Land". Los Angeles Times. 30 June 2002. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Loh, Dylan M.H. (2024). China's Rising Foreign Ministry: Practices and Representations of Assertive Diplomacy. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9781503638204.

- ^ "Vietnam-Chine : conversation téléphonique entre Nguyên Phu Trong et Xi Jinping". Nhân Dân. Archived from the original on 2021-05-08. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- ^ a b Shi, Jiangtao (2 November 2022). "China, Vietnam vow closer ties, to 'manage' South China Sea dispute in joint focus on external challenges". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ Liu, Zhen (27 June 2023). "Chinese Premier Li Qiang meets Vietnamese counterpart to promote cooperation". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ "Prime Minister meets top Chinese legislator in Beijing". Việt Nam News. 27 June 2023. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ "PM meets leader of Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference". Việt Nam News. 28 June 2023. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ "Wang Huning Meets with General Secretary of CPV Central Committee and State President To Lam". FMPRC.gov.cn. 2024-08-20. Retrieved 2024-08-20.

- ^ "Vietnam, China to expand rail links, cross-border payments". Barneo Bulletine. 13 October 2024. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ a b Garlick, Jeremy (2024). Advantage China: Agent of Change in an Era of Global Disruption. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-350-25231-8.

- ^ Ministry of Industry and Trade (Vietnam) (2023). Báo cáo Xuất nhập khẩu Việt Nam năm 2022 [Vietnam Import - Export Report 2022] (PDF). Hà Nội: Hong Duc Publishing House (Vietnam). pp. 248–251. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-07-01. Retrieved 2023-07-01.

- ^ a b c "China, Vietnam find love". Asia Times. 21 July 2005. Archived from the original on 23 July 2005. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- ^ a b "China, Vietnam Seek Ways to Improve Bilateral Relations". China Radio International. 5 October 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ "Vietnam - China import-export turnover reaches US$ 117 billion". en.nhandan.org.vn.

- ^ "State owned Thai Nguyen Iron and Steel faces bankruptcy in Vietnam". SteelGuru India. Retrieved 2020-02-10.

- ^ Nguyen T.H.K.; et al. (May 26, 2018). "The "same bed, different dreams" of Vietnam and China: how (mis)trust could make or break it". Thanh Tay University. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- ^ Gulotty, Robert; Li, Xiaojun (2019-07-30). "Anticipating exclusion: Global supply chains and Chinese business responses to the Trans-Pacific Partnership". Business and Politics. 22 (2): 253–278. doi:10.1017/bap.2019.8. S2CID 201359183.

- ^ Schuettler, Darren; Pullin, Richard (2018-06-10). "Vietnam police halt protests against new economic zones". Reuters.

- ^ "Vietnamese see special economic zones as assault from China". 2018-06-07.

- ^ "China is going crazy for durians". The Economist. 13 June 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ AP via Chron.com. "Vietnam Plans Live-fire Drill after China Dispute". 10 June 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "China's Navy passes first aircraft-carrier into service" Archived 2012-09-30 at the Wayback Machine. Voice of Russia. 25 September 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ a b "Vietnam slams 'absurd' China protest over islands". gulfnews.com. 23 June 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "China announces creating Sansha city". ChinaBeijing.org. 24 June 2012. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "Vietnam breaks up anti-China protests". BBC. 9 December 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ "Prime Minister Suga Visits Viet Nam and Indonesia". MOFA, Japan. October 20, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ "Suga and Vietnamese PM meet, with focus on economic and defense cooperation". Japan Times. October 19, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ "Japan inks deal to export defense assets to Vietnam amid China worry". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 2021-09-12.

- ^ "Vietnam Accuses Chinese Vessel of Hitting Its Fishing Boat". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Hanoi Says Chinese Ships Ram, Sink Vietnamese Fishing Boat". Vietnam Tribune. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Roszko, Edyta (December 2016). "Fishers and Territorial Anxieties in China and Vietnam: Narratives of the South China Sea Beyond the Frame of the Nation" (PDF). Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review. 21: 25.

- ^ a b Thu, Huong Le. "Rough Waters Ahead for Vietnam-China Relations". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- ^ "Vietnam anti-China protest: Factories burnt". BBC. 14 May 2020.

- ^ "China rebuts Vietnam charge of it forcing territorial dispute". China News. Net. Archived from the original on 15 June 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ Hai, Thu (2 June 2014). "Chinese ships launch waves of attacks against Vietnamese vessels". VGP News.

- ^ "Chapter 4: How Asians View Each Other". Pew Research Center. 2014-07-14. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ Chandran, Nyshka (July 24, 2017). "China reportedly threatens Vietnam into ending energy exploration in South China Sea". CNBC.

- ^ Hayton, Bill (July 24, 2017). "Vietnam halts South China Sea drilling". BBC News.

- ^ "Chinese ships attack Vietnamese boat in the disputed waters". Vietnam Insider. 14 June 2020.

- ^ "Vietnam's Struggles in the S. China Sea: Challenges and Opportunities". The Maritime Executive. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- ^ "China, Vietnam Try to Make Amends After Stormy Start to 2020 | Voice of America - English". www.voanews.com. 2 September 2020. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- ^ Hoang, Phuong (2019-03-26). "Domestic Protests and Foreign Policy: An Examination of Anti-China Protests in Vietnam and Vietnamese Policy Towards China Regarding the South China Sea". Journal of Asian Security and International Affairs. 6: 1–29. doi:10.1177/2347797019826747.

- ^ Jamie Tarabay (April 23, 2020). "Vietnamese Hackers Targeted China Officials at Heart of Outbreak". Bloomberg.com.

- ^ Thayer, Carl. "Did Vietnamese Hackers Target the Chinese Government to Get Information on COVID-19?". thediplomat.com.

- ^ Hui, Mary (23 April 2020). "Vietnam's early coronavirus response reportedly included hackers who targeted China". Quartz.

- ^ Le, Niharika Mandhana and Lam (2020-07-30). "Vietnam Was Crushing the Coronavirus—Now It's Got a New Outbreak". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- ^ "Vietnam PM orders crackdown on illegal immigrants amid fresh coronavirus outbreaks". hanoitimes.vn. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- ^ An, Chau (13 May 2020). "Israeli company uncovers cyberattack on Vietnam, neighbors by China-linked group". VN Express.

- ^ "Vietnam says it will not side against China, as US' Kamala Harris visits". sg.news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2021-09-19.

- ^ "Vietnam says it will not side against China, before US' Kamala Harris visits country". The Star. Retrieved 2021-09-19.

- ^ "Chinese coast guard ship chased out of Vietnam waters". Radio Free Asia.

- ^ a b c Guarascio, Francesco; Vu, Khanh; Nguyen, Phuong (December 12, 2023). "Vietnam Boosts China Ties as 'Bamboo Diplomacy' Follows US Upgrade". Reuters. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ Dinh, Hau; Rising, David (2024-09-30). "Crew of Vietnamese fishing boat injured in an attack in the South China Sea, state media say". Associated Press. Retrieved 2024-10-01.

- ^ "Philippines condemns China attack of Vietnamese fishermen". Voice of America. Agence France-Presse. 2024-10-04. Retrieved 2024-10-05.

Bibliography

[edit]- Amer, Ramses. "China, Vietnam, and the South China Sea: disputes and dispute management." Ocean Development & International Law 45.1 (2014): 17–40.

- Ang, Cheng Guan. Southeast Asia's cold war: An interpretive history (U of Hawaii Press, 2018) online review.

- Ang, Cheng Guan. Vietnamese Communist Relations with China and the Second Indo-China Conflict, 1956-1962 (MacFarland, 1997).

- Ang, Cheng Guan. Southeast Asia after the Cold War: A Contemporary History (Singapore: NUS Press, 2019).

- Blazevic, Jason J. "Navigating the security dilemma: China, Vietnam, and the South China Sea." Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 31.4 (2012): 79–108. online

- Brook, Timothy, Michael van Walt van Praag, and Miek Boltjes, eds. Sacred mandates: Asian international relations since Chinggis Khan (University of Chicago Press, 2018).

- Chakraborti, Tridib. "China and Vietnam in the South China Sea Dispute: A Creeping ‘Conflict–Peace–Trepidation’Syndrome." China Report 48.3 (2012): 283–301. online

- Chen, King C. Vietnam and China, 1938-1954 (Princeton University Press, 2015). excerpt

- Cuong, Nguyen Xuan, and Nguyen Thi Phuong Hoa. "Achievements and Problems in Vietnam: China Relations from 1991 to the Present." China Report 54.3 (2018): 306–324. online

- Fravel, M. Taylor. Active Defense: China's Military Strategy Since 1949 (Princeton UP, 2019).

- Garver, John W. China's quest: the history of the foreign relations of the people's Republic of China (Oxford University Press, 2015).

- Ha, Lam Thanh, and Nguyen Duc Phuc. "The US-China Trade War: Impact on Vietnam." (2019). online Archived 2022-08-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Han, Xiaorong. "Exiled to the ancestral land: The resettlement, stratification and assimilation of the refugees from Vietnam in China." International Journal of Asian Studies 10.1 (2013): 25–46.

- Kang, David C., et al. "War, rebellion, and intervention under hierarchy: Vietnam–China relations, 1365 to 1841." Journal of Conflict Resolution 63.4 (2019): 896–922. online

- Khoo, Nicholas. "Revisiting the Termination of the Sino–Vietnamese Alliance, 1975–1979." European Journal of East Asian Studies 9.2 (2010): 321–361. online

- Kurlantzick, Joshua. China-Vietnam Military Clash (Washington: Council on Foreign Relations, 2015). online

- Le Hong Hiep (December 2013). "Vietnam's Hedging Strategy against China since Normalization". Contemporary Southeast Asia. 35 (3): 333–368. doi:10.1355/cs35-3b. S2CID 153762989.

- Liegl, Markus B. China's use of military force in foreign affairs: The dragon strikes (Taylor & Francis, 2017). excerpt

- Nguyen, Anh Ngoc. "Three Structures of Vietnam-China Relations: a View from the Structural Constructivist Theory." East Asia 38.2 (2021): 123–138. online

- Nguyen, Hanh Thi My. "Application of Center-Periphery Theory to the Study of Vietnam-China Relations in the Middle Ages." Southeast Asian Studies 8.1 (2019): 53–79. online

- Path, Kosal. "China's Economic Sanctions against Vietnam, 1975-1978." China Quarterly (2012) Vol. 212, pp 1040–1058.

- Path, Kosal. "The economic factor in the Sino-Vietnamese split, 1972–75: an analysis of Vietnamese archival sources." Cold War History 11.4 (2011): 519–555.

- Path, Kosal. "The Sino-Vietnamese Dispute over Territorial Claims, 1974–1978: Vietnamese Nationalism and its Consequences." International Journal of Asian Studies 8.2 (2011): 189–220. online

- Taylor, K. W. A History of the Vietnamese (Cambridge University Press, 2013). ISBN 0521875862.

- Wills Jr., John E. “Functional, Not Fossilized: Qing Tribute Relations with Đại Việt (Vietnam) and Siam (Thailand), 1700–1820,” T'oung Pao, Vol. 98 Issue 4–5, (2012), 439–47

- Zhang, Xiaoming. Deng Xiaoping's Long War: The Military Conflict Between China and Vietnam, 1979-1991 (U of North Carolina Press 2015) excerpt

- Zhang, Xiaoming. "Deng Xiaoping and China's Decision to go to War with Vietnam." Journal of Cold War Studies 12.3 (2010): 3-29 online

- Zhang, Xiaoming. "China's 1979 war with Vietnam: a reassessment." China Quarterly (2005): 851–874. online

External links

[edit]- Chinese embassy in Vietnam (in Chinese)

- Vietnamese embassy in Beijing, China (in Vietnamese and Chinese)