Phenoxymethylpenicillin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Veetids, Apocillin,[1] others |

| Other names | penicillin phenoxymethyl, penicillin V, penicillin VK |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a685015 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60% |

| Protein binding | 80% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 30–60 min |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.566 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

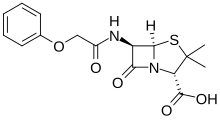

| Formula | C16H18N2O5S |

| Molar mass | 350.39 g·mol−1 |

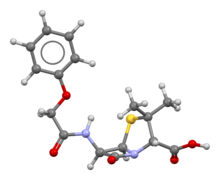

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 120–128 °C (248–262 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Phenoxymethylpenicillin, also known as penicillin V (PcV) and penicillin VK, is an antibiotic useful for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections.[2] Specifically it is used for the treatment of strep throat, otitis media, and cellulitis.[2] It is also used to prevent rheumatic fever and to prevent infections following removal of the spleen.[2] It is given by mouth.[2]

Side effects include diarrhea, nausea, and allergic reactions including anaphylaxis.[2] It is not recommended in those with a history of penicillin allergy.[2] It is relatively safe for use during pregnancy.[3] It is in the penicillin and beta lactam family of medications.[4] It usually results in bacterial death.[4]

Phenoxymethylpenicillin was first made in 1948 by Eli Lilly.[5]: 121 It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[6] It is available as a generic medication.[4] In 2022, it was the 259th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 1 million prescriptions.[7][8]

Medical uses

[edit]Specific uses for phenoxymethylpenicillin include:[9][10]

- Infections caused by Streptococcus pyogenes

- Tonsillitis

- Pharyngitis

- Skin infections

- Anthrax (mild uncomplicated infections)

- Lyme disease (early stage in pregnant women or young children)

- Rheumatic fever (primary and secondary prophylaxis)

- Streptococcal skin infections

- Spleen disorders (pneumococcal infection prophylaxis)

- Initial treatment for dental abscesses

- Moderate-to-severe gingivitis (with metronidazole)

- Avulsion injuries of teeth (as an alternative to tetracycline)

- Blood infection prophylaxis in children with sickle cell disease.

Penicillin V is sometimes used in the treatment of odontogenic infections.[citation needed]

It is less active than benzylpenicillin (penicillin G) against Gram-negative bacteria.[11][12] Phenoxymethylpenicillin has a range of antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria that is similar to that of benzylpenicillin and a similar mode of action, but it is substantially less active than benzylpenicillin against Gram-negative bacteria.[11][12]

Phenoxymethylpenicillin is more acid-stable than benzylpenicillin, which allows it to be given orally.[citation needed]

Phenoxymethylpenicillin is usually used only for the treatment of mild to moderate infections, and not for severe or deep-seated infections since absorption can be unpredictable. Except for the treatment or prevention of infection with Streptococcus pyogenes (which is uniformly sensitive to penicillin), therapy should be guided by bacteriological studies (including sensitivity tests) and by clinical response.[13] People treated initially with parenteral benzylpenicillin may continue treatment with phenoxymethylpenicillin by mouth once a satisfactory response has been obtained.[9]

It is not active against beta-lactamase-producing bacteria, which include many strains of Staphylococci.[13]

Adverse effects

[edit]Phenoxymethylpenicillin is usually well tolerated but may occasionally cause transient nausea, vomiting, epigastric distress, diarrhea, constipation, acidic smell to urine and black hairy tongue. A previous hypersensitivity reaction to any penicillin is a contraindication.[9][13]

Mechanism of action

[edit]The mechanism of phenoxymethylpenicillin is identical to that of all other penicillins. It exerts a bactericidal action against penicillin-sensitive microorganisms during the stage of active multiplication. It acts by inhibiting the biosynthesis of cell-wall peptidoglycan.[14]

Compendial status

[edit]History

[edit]The Austrian pharmaceutical company, Biochemie, was founded in Kundl in July 1946 at the site of a derelict brewery, at the suggestion of a French officer, Michel Rambaud (a chemist), who was able to obtain a small amount of Penicillium start culture from France. Contamination of the fermentation tanks was a persistent problem and in 1951, the company biologist, Ernst Brandl, attempted to solve this by adding phenoxyethanol to the tanks as an anti-bacterial disinfectant. This resulted unexpectedly in an increase in penicillin production: but, the penicillin produced was not benzylpenicillin, but phenoxymethylpenicillin. Phenoxyethanol was fermented to phenoxyacetic acid[16] in the tanks, which was then incorporated into penicillin via biosynthesis. Importantly, Brandl realised that phenoxymethylpenicillin is not destroyed by stomach acid and can therefore be given by mouth. Phenoxymethyl penicillin was originally discovered by Eli Lilly in 1948 as part of their efforts to study penicillin precursors, but was not further exploited, and there is no evidence that Lilly understood the significance of their discovery at the time.[5]: 119–121 [17]

Biochemie is part of Sandoz.[citation needed]

Society and culture

[edit]Names

[edit]There were four named penicillins at the time penicillin V was discovered (penicillins I, II, III, IV), however, Penicillin V was named "V" for Vertraulich (German for confidential);[5]: 121 it was not named for the Roman numeral "5". Penicillin VK is the potassium salt of penicillin V (K is the chemical symbol for potassium).[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "Apocillin". Felleskatalogen (in Norwegian). LMI (Legemiddelindustrien). Retrieved 23 June 2018.

fenoksymetylpenicillin

- ^ a b c d e f World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ^ Hamilton R (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 95. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ^ a b c "Penicillin V". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b c Greenwood D (2008). "Wonder Drugs". Antimicrobial Drugs: Chronicle of a Twentieth Century Medical Triumph. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-953484-5. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "PenicillinV Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Sweetman S., ed. (2002). Martindale: The complete drug reference (Electronic version ed.). London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain and the Pharmaceutical Press.

- ^ Rossi S., ed. (2006). Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd. ISBN 0-9757919-2-3.

- ^ a b Garrod LP (February 1960). "Relative antibacterial activity of three penicillins". British Medical Journal. 1 (5172): 527–529. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5172.527. PMC 1966560. PMID 13826674.

- ^ a b Garrod LP (December 1960). "The relative antibacterial activity of four penicillins". British Medical Journal. 2 (5214): 1695–1696. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5214.1695. PMC 2098302. PMID 13703756.

- ^ a b c "Penicillin V Potassium tablet: Drug Label Sections". U.S. National Library of Medicine, Daily Med: Current Medication Information. December 2006. Archived from the original on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ^ Yocum RR, Rasmussen JR, Strominger JL (May 1980). "The mechanism of action of penicillin. Penicillin acylates the active site of Bacillus stearothermophilus D-alanine carboxypeptidase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 255 (9): 3977–3986. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)85621-1. PMID 7372662.

- ^ "Index (BP 2009)" (PDF). British Pharmacopoeia Commission Secretariat. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ^ "Phenoxyacetic acid". PubChem. Bethesda, MD, USA: National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. 26 December 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ Behrens OK, Corse J (September 1948). "Biosynthesis of penicillins; biological precursors for benzylpenicillin (penicillin G)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 175 (2): 751–764. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)57194-5. PMID 18880772.