Pauline Pfeiffer

Pauline Pfeiffer | |

|---|---|

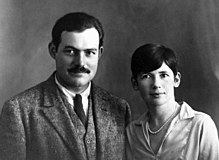

Ernest and Pauline Hemingway in Paris, 1927 | |

| Born | Pauline Marie Pfeiffer July 22, 1895 Parkersburg, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | October 1, 1951 (aged 56) Hollywood, California, U.S. |

| Education | |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

Pauline Marie Pfeiffer (July 22, 1895 – October 1, 1951) was an American journalist and the second wife of writer Ernest Hemingway.[1]

Early life

[edit]Pfeiffer was born in Parkersburg, Iowa, to Paul Pfeiffer, a real estate agent, and Mary Alice Downey,[2] on July 22, 1895, moving to St. Louis in 1901, where she went to school at Visitation Academy of St. Louis. Although her family later moved to Piggott, Arkansas, Pfeiffer stayed in Missouri to study at the University of Missouri School of Journalism, graduating in 1918. After working at newspapers in Cleveland and New York, Pfeiffer switched to magazines, working for Vanity Fair and Vogue. A move to Paris for Vogue led to her meeting Hemingway and his first wife, Hadley Richardson, in 1926.[3]

Marriage to Hemingway

[edit]In the spring of 1926, Hadley Richardson, the first wife of Ernest Hemingway, became aware of Hemingway's affair with Pauline,[4] and in July, Pauline joined the couple for their annual trip to Pamplona.[5] Upon their return to Paris, Hadley and Hemingway decided to separate, and in November, Hadley formally requested a divorce.[6] They were divorced in January 1927.[3]

Hemingway married Pauline in May 1927, and they went to Le Grau-du-Roi on a honeymoon.[7][8] Pauline's family was wealthy and Catholic; before the marriage, Hemingway converted to Catholicism.[9] By the end of the year Pauline, who was pregnant, wanted to move back to America. John Dos Passos recommended Key West, and they left Paris in March 1928.[10]

They had two children, Patrick and Gloria (born Gregory). Hemingway drew upon Pfeiffer's difficult labor with one child as the basis for his character Catherine's death in A Farewell to Arms. Pfeiffer's devout Roman Catholic beliefs led to her support of the Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War while Hemingway backed the Republicans.[3]

In 1937, on a trip to Spain, Hemingway began an affair with Martha Gellhorn.[3] Pfeiffer and he were divorced on November 4, 1940, and he married Gellhorn three weeks later.[3]

Later life and death

[edit]Pfeiffer lived in Key West, with frequent visits to California, until her death on October 1, 1951, at age 56.[3] Her death was attributed to an acute state of shock related to Gregory's arrest and a subsequent phone call from Ernest. Gregory, later known as Gloria, who had experienced gender identity issues for most of her life,[11] had been arrested for entering the women's restroom in a movie theater.

Years later, after becoming a medical doctor, Gloria interpreted her mother's autopsy report as indicating that she had died due to a pheochromocytoma tumor on one of her adrenal glands. Her theory was that the phone call from Ernest had caused the tumor to secrete excessive adrenaline and then stop, resulting in a change in blood pressure that caused her mother to go into acute shock and led to her death.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ Harris, Peggy (Associated Press) (30 July 2000). Ernest Hemingway Museum Popular in Quiet Farm Town, The Tuscaloosa News. Retrieved November 4, 2010

- ^ 1900 United States Federal Census

- ^ a b c d e f Kert, Bernice, The Hemingway Women: Those Who Loved Him – the Wives and Others, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 1983.

- ^ Baker (1972), 43

- ^ Mellow (1992), 333

- ^ Mellow (1992), 338–340

- ^ Meyers (1985), 172

- ^ Mellow (1992), 348–353

- ^ Mellow (1992, 294

- ^ Meyers (1985), 204}

- ^ Miami Herald: Carol Rabin Miller, "Gender of Hemingway's son at center of feud," September 22, 2003. Retrieved June 27, 2011

- ^ "Gloria Hemingway (1931–2001) writer, doctor".

Sources

[edit]- Baker, Carlos. Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story. Charles Scribner's Sons (1969). New York. ISBN 978-0-02-001690-8

- Mellow, James R. Hemingway: A Life Without Consequences. Houghton Mifflin (1992). New York. ISBN 0-395-37777-3

- Meyers, Jeffrey. Hemingway: A Biography. Macmillan (1985). London. ISBN 0-333-42126-4