A Farewell to Arms (1932 film)

| A Farewell to Arms | |

|---|---|

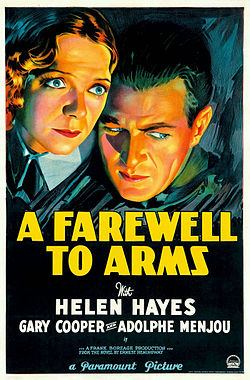

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Frank Borzage |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | A Farewell to Arms 1929 novel by Ernest Hemingway and play written by Laurence Stallings. |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Charles Lang |

| Edited by | |

| Music by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures (original release) Warner Bros. Pictures (1949 reissue) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 88 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $900,000[1] |

| Box office | $1 million (U.S. and Canada rentals)[2] |

A Farewell to Arms is a 1932 American pre-Code melodrama film[3] directed by Frank Borzage and starring Helen Hayes, Gary Cooper and Adolphe Menjou.[4] Based on the 1929 semi-autobiographical novel A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway, with a screenplay by Oliver H. P. Garrett and Benjamin Glazer, the film is about a tragic romantic love affair between an American ambulance driver and an English nurse in Italy during World War I. The film received Academy Awards for Best Cinematography and Best Sound and was nominated for Best Picture and Best Art Direction.[4]

In 1960, the film entered the public domain in the United States because the last claimant, David O. Selznick, did not renew its copyright registration in the 28th year after publication.[5]

The original Broadway play starred Glenn Anders and Elissa Landi and was staged at the National Theatre from September 22, 1930, to October 1930.[6][7]

Plot

[edit]On the Italian front during World War I, Lieutenant Frederic Henry is an American serving as an ambulance driver with the Italian Army. While carousing with his friend, Italian captain Rinaldi, a bombing raid takes place. Frederic meets English Red Cross nurse Catherine Barkley in a dark stairway. Frederic is inebriated and makes a poor first impression on Catherine and her friend Fergie.

At a concert, Catherine reveals that she had been engaged to a soldier who was killed in battle. Frederic tries to kiss her and she slaps him, but soon after, she asks him to kiss her again. He seduces her and tells her that he loves her.

Before departing for the front, Frederic tells Catherine that he will survive the battle unscathed. Catherine gives him her St. Anthony medal. However, Rinaldi had orchestrated the separation. Catherine is transferred to Milan.

At the front, Frederic is badly wounded by an artillery shell. He is sent to a hospital in Milan where Catherine rushes to his bed to embrace him. A priest performs an unofficial wedding for Frederic and Catherine. Months later, Fergie admonishes them for marrying and warns Frederic that she will kill him if Catherine becomes pregnant. Back at the hospital, Frederic is informed that his convalescent leave has been canceled. While waiting for his train, Catherine tells Frederic that she is scared of each of them dying. He promises that he will always return. Later, Catherine reveals to Fergie that she is pregnant and that she is traveling to Switzerland to give birth.

While apart, Catherine writes letters to Frederic, never revealing her pregnancy. In Turin, Rinaldi tries to entice Frederic to have some fun, but Frederic is intent on writing to Catherine. Rinaldi secretly ensures that all of Catherine's letters are returned to her without reaching Frederic. The hospital at Milan also returns Frederic's letters. He deserts and travels to Milan to find Catherine. In Milan, Frederic finds Fergie, who refuses to tell him anything other than that Catherine was pregnant and has gone. Rinaldi reveals to Frederic that Catherine is going to have a baby and that she is in Brissago, apologizing for his part in keeping the lovers apart.

While Frederic is rushing to Brissago, Catherine is taken to a hospital as the time of birth is near. Frederic arrives as Catherine undergoes a Caesarean section. After the operation, a surgeon tells Frederic that the baby boy was stillborn. When Catherine regains consciousness, she and Frederic plan their future, but she fears that she will die. Frederic tells her that they can never really be parted. She dies in Frederic's arms as the sun rises. Frederic lifts her body and turns slowly toward the window sobbing, "Peace, Peace."

Cast

[edit]- Helen Hayes as Catherine Barkley

- Gary Cooper as Lieutenant Frederic Henry

- Adolphe Menjou as Captain Rinaldi

- Mary Philips as Helen Ferguson

- Jack La Rue as Priest

- Blanche Friderici as Head Nurse

- Mary Forbes as Miss Van Campen

- Gilbert Emery as British Major[4]

- Agostino Borgato as Giulio (uncredited)

- Tom Ricketts as Count Greffi (uncredited)

Production

[edit]The film was released in multiple versions with different endings, one with Catherine's death, one in which she lives and another in which her fate is ambiguous. Although international audiences saw only the version with tragic ending, some American theaters were offered a choice.[8]

As the film was released before strict enforcement of the Production Code, its themes and content became problematic during the era of enforcement when the film was prepared for rereleases to film and television.[9][10] The film's original length was 89 minutes but was cut to 78 minutes for a 1938 reissue. The 89-minute version, which had not been seen since the film's original 1932 release, was long believed to be lost. However, a nitrate print was located in the David O. Selznick vaults and the uncut film was released on DVD in 1999 by Image Entertainment.[11]

Music

[edit]The film's soundtrack includes selections from the Wagner operas Tristan und Isolde ("Liebestod"), Das Rheingold and Siegfried, as well as the storm passage from Tchaikovsky's symphonic poem Francesca da Rimini.[12]

Reception

[edit]

In a contemporary review for The New York Times, critic Mordaunt Hall wrote:

Bravely as it is produced for the most part, there is too much sentiment and not enough strength in the pictorial conception of Ernest Hemingway's novel ... Notwithstanding the undeniable artistry of the photography, the fine recording of voices and Frank Borzage's occasional excellent directorial ideas, one misses the author's vivid descriptions and the telling dialogue ... It is Mr. Borzage rather than Mr. Hemingway who prevails in this film and the incidents frequently are unfurled in a jerky fashion. To be true it was an extremely difficult task to tackle, a rather hopeless one in fact, considering that the story is told in the first person. Possibly if any one has not read Mr. Hemingway's book, the picture will appeal as a rather interesting if tragic romance. In some of the scenes, however, the producers appear to take it for granted that the spectators have read the book.[13]

Mae Tinée of the Chicago Tribune wrote: "'A Farewell to Arms' is rich with all the attributes that make for a completely satisfying screen play. Humor, pathos, suspense, romance, tragedy—all are there. And it has the human touch that endears."[14]

Irene Thirer wrote in the New York Daily News: "The picture is heart-rending and throat-hurting. It moves you so deeply that it is often difficult to see the screen, for the haze which mists your tear-filled eyes. Frank Borzage's direction is nothing less than superb. ... He tugs at your heartstrings until you positively can't stand it any more. And yet he gives a human treatment, indeed, with abundant charm and none of the saccharine."[15]

Awards

[edit]The film was nominated for four Academy Awards, winning two:[16]

- Academy Award for Best Picture (nominee)[4]

- Academy Award for Art Direction (nominee)

- Academy Award for Best Cinematography (winner)

- Academy Award for Best Sound Recording – Franklin Hansen (winner)

See also

[edit]- List of films in the public domain in the United States

- The House That Shadows Built (1931 promotional film by Paramount with excerpt of film showing Eleanor Boardman, later replaced by Hayes)

References

[edit]- ^ Schallert, Edwin (October 16, 1932). "Film Costs Hit Both Extremes". Los Angeles Times. p. B13. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Cohn, Lawrence (October 15, 1990). "All Time Film Rental Champs". Variety. p. M-140. ISSN 0042-2738.

- ^ Schatz, Thomas (1981). Hollywood Genres: Formulas, Filmmaking, and the Studio System. New York: Random House. p. 222. ISBN 0-394-32255-X.

- ^ a b c d Erickson, Hal (October 16, 2007). "A Farewell to Arms (1932)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ Pierce, David (June 2007). "Forgotten Faces: Why Some of Our Cinema Heritage Is Part of the Public Domain". Film History: An International Journal. 19 (2): 125–43. doi:10.2979/FIL.2007.19.2.125. ISSN 0892-2160. JSTOR 25165419. OCLC 15122313. S2CID 191633078.

- ^ "A Farewell to Arms". Internet Broadway Database.

- ^ Unlike most pre-1950 Paramount sound features, A Farewell to Arms was not sold to what is now known as Universal Television. Warner Bros. acquired the rights at an unknown date with the intention to remake the film, but never did. However, Warner Brothers DID re-release the movie in the later forties. WB replaced the original Paramount openings and closings with its circa 1948 logo and completely re-filmed the opening credits and end title. The film would end-up in the package of films sold to Associated Artists Productions in 1956, that company would be sold to United Artists two years later.

- ^ "A Farewell to Arms (1932) – Notes". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ "A Farewell to Arms (1932) – Home Video Reviews". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ "A Farewell to Arms (1932) – Notes". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ "A Farewell to Arms (1932) – Alternate Versions". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ Slowik, Michael (October 21, 2014). After the Silents: Hollywood Film Music in the Early Sound Era, 1926–1934. Columbia University Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-2315-3550-2.

- ^ Hall, Mordaunt (December 9, 1932). "Helen Hayes, Gary Cooper and Adolphe Menjou in a Film of Hemingway's "Farewell to Arms"". The New York Times. p. 26.

- ^ Tinée, Mae (December 23, 1932). "An Ace Movie Starts Oriental on New Policy". Chicago Tribune. p. 17.

- ^ Thirer, Irene (December 9, 1932). "'Farewell to Arms' Poignant Picture". New York Daily News. p. 62.

- ^ "The 6th Academy Awards (1934) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Tibbetts, John C., and James M. Welsh, eds. The Encyclopedia of Novels Into Film (2nd ed. 2005) pp 124–126.

External links

[edit]- A Farewell to Arms on YouTube

- A Farewell to Arms at IMDb

- A Farewell to Arms at the TCM Movie Database

- A Farewell to Arms at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- A Farewell to Arms at Rotten Tomatoes

- A Farewell to Arms is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

Streaming audio

[edit]- A Farewell to Arms on Studio One, February 17, 1948

- A Farewell to Arms on NBC University Theater, August 6, 1948

- 1932 films

- 1930s English-language films

- 1932 romantic drama films

- American romantic drama films

- American black-and-white films

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on works by Ernest Hemingway

- Films directed by Frank Borzage

- Films set in Italy

- Films whose cinematographer won the Best Cinematography Academy Award

- Paramount Pictures films

- American war drama films

- American war romance films

- World War I films set on the Italian Front

- Films with screenplays by Benjamin Glazer

- 1932 war films

- 1930s American films

- English-language romantic drama films

- English-language war drama films

- Films scored by W. Franke Harling

- Films scored by Bernhard Kaun

- Films scored by John Leipold

- Films scored by Ralph Rainger

- 1930s war drama films