Ignatios of Constantinople

Importance

[edit]Ignatius of Constantinople | |

|---|---|

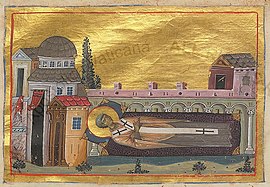

Ignatius of Constantinople, Northern tympanon, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul | |

| Patriarch of Constantinople | |

| Born | 798 Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey) |

| Died | 23 October 877 (aged 78–79) Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey) |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

| Feast | October 23 |

St. Ignatius was the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople from 847 to 858 and from 867 to 877. Ignatius lived during a complex time for the Byzantine Empire. The Iconoclast Controversy was ongoing, Boris I of Bulgaria converted to Christianity in 864, and the Roman pontiffs repeatedly challenged the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Eastern Church in Bulgaria. As patriarch, Ignatius denounced iconoclasm, secured jurisdiction over Bulgaria for the Eastern Church, and played an important role in conflicts over papal supremacy.

Ignatius of Constantinople | |

|---|---|

| Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople | |

| Installed | 847 |

| Term ended | 858, 867–877 |

| Personal details | |

| Denomination | Chalcedonian Christianity |

Context

[edit]

At the time St. Ignatius lived, relations remained tense between the Eastern and Western Churches. Byzantium was embroiled in several controversies. The pope, as head of the Western Church, maintained that he had supreme and universal authority over both Churches, but the Eastern Church opposed his claim. Indeed, Photius, who replaced Ignatius as patriarch when was deposed in 859, condemned the pope and the Western Church in 867 for adding the filioque (“and the Son”) to the Nicene Creed. The Eastern and Western churches also competed to convert the Slavs, and both Churches sought to dominate the Christianization of Bulgaria. At that time, the Eastern Church faced internal struggles, too. Most notably, the Church had not yet resolved the Iconoclast Controversy. Although the seventh ecumenical council, also known as the Second Council of Nicaea, had decided in favor of icon veneration in 787, Iconoclasm continued.

Birth and early life

[edit]St. Ignatius or Ignatios (Greek: Ἰγνάτιος) was born in 798 and died on October 23, 877. He was originally named Niketas, and was a son of the Emperor Michael I and Empress Prokopia. As a child, Niketas was appointed nominal commander of the new corps of imperial guards, the Hikanatoi. When he was fourteen, Leo the Armenian had Niketas forcibly castrated, which made him ineligible to become emperor, and effectively imprisoned in a monastery after his father's deposition in 813. As a monk, he took the name Ignatius and eventually became abbot. He also founded three monasteries on the Princes' Islands, a favorite place for exiling tonsured members of the imperial house.

Patriarchate

[edit]Theodora appointed St. Ignatius as patriarch in 847 in part because he supported venerating icons.[1] As patriarch, Ignatius became an important ally for Theodora in the midst of the Iconoclast Controversy. Choosing an iconodule as patriarch secured Theodora's power, since she was more at risk of being overthrown by iconodules than by iconoclasts. Ignatius served as Patriarch of Constantinople from July 4, 847 to October 23, 858 and from November 23, 867 to his death on October 23, 877.

Deposition and ascent of Photius

[edit]The imperial court's resentment of St. Ignatius began when he excommunicated a high ranking imperial court member, Bardas, for incest.[2] Bardas exiled Empress Theodora, attempting to gain more power, but Ignatius refused to approve of this. Emperor Michael III, influenced by Bardas, removed Ignatius as patriarch and exiled him in 857. A synod was convened which deposed St. Ignatius on the basis of a canon which prohibited a bishop being appointed by a secular power. Photius, an associate of Bardas, was made patriarch on Christmas Day of 858.

A schism resulted from Photius’ election because many bishops saw St. Ignatius’ exit as illegitimate. St. Ignatius had only a few supporters once Photius became patriarch. Most agreed that St. Ignatius had legitimately resigned, but some of his supporters appealed to Rome for him. A synod of 170 bishops deposed and anathematized St. Ignatius, but the schism escalated when Pope St. Nicholas I stepped in. The Roman see thought itself to have universal jurisdiction over all bishops, but Constantinople did not believe that Rome had this right.

Intervention of Pope St. Nicholas I and Pope Hadrian

[edit]Pope St. Nicholas I questioned Photius’ legitimate status as patriarch. Papal legates retried St. Ignatius in a synod in 861, which said that Photius was the legitimate patriarch, but Nicholas rejected that synod and held his own synod which condemned Photius and declared Ignatius the legitimate patriarch. He excommunicated Photius and declared all his ordinations invalid. Emperor Michael III rejected Nicholas’ synod and accepted the one that had approved Ignatius’ deposition.

Photius excommunicated Pope St. Nicholas and all Latin Christians in a council in Constantinople in 867 for believing that the Holy Spirit proceeds from both the Father and the Son, as well as adding that belief (the filioque) to the Nicene Creed in the West. He did this even though St. Augustine,[3] St. Hilary,[3] St. Ambrose,[3] St. Leo the Great,[3] St. Cyril,[3] St. Maximus the Confessor,[3] and many other saints and theologians in both the West and East explicitly taught the eternal procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father and the Son. Nicholas died before hearing about the council, but his successor Pope Hadrian II condemned it. The controversy over the filioque played a key role in the eventual schism that would split the two Churches for over a thousand years.

Emperor Michael III was murdered and Basileios, his co-emperor, replaced him in 867. Basileios exiled Photius and restored St. Ignatius as patriarch. Basileios effectively undid the last nine years of church history, restoring the Ignatian bishops and nullifying everything Photius did, securing his political position as emperor. Pope Hadrian II held a council in 869 which condemned Photius, rejecting and burning the council of 867. The pope's council said that Photius’ ordinations were invalid and if the bishops wanted to be part of the council, they had to sign a document condemning Photius and affirming the supremacy of Rome. A council was convened at Constantinople in 869 for the eastern bishops to review Pope Hadrian's decision. The council met, condemned Photius, and reinstated St. Ignatius, but many eastern bishops did not show up and the papal supremacy canons were rejected.

Securing Bulgaria for the East

[edit]The Christianization of the Slavs created conflict between the Eastern and Western Churches as both vied for control of the new Bulgarian church. Ecclesiastical jurisdiction over Bulgaria meant political influence in the khanate as well. Emperor Michael III attacked Bulgaria and caught Boris, the Bulgar khan, off guard. Boris was forced to submit to the emperor and was baptized in 864, taking the Christian name of Micheal.[4] At the Eighth Ecumenical Council council held in 869 in Constantinople, the Bulgarians deferred to Constantinople rather than Rome, thereby confirming that the Bulgarian church submitted to Constantinople, not Rome. A papal letter to St. Ignatius threatened that he would not be reinstated if he interfered with Roman plans in Bulgaria, but he did not read the letter and chose an archbishop for Bulgaria. Rome still accepted the provisions of the council because it upheld the condemnation of Photius.

After death

[edit]After St. Ignatius died in 877, Photius became the Patriarch of Constantinople once again, since Ignatius named him as his successor.[5] In the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches, he is venerated as a saint, with a feast day of October 23.

See also

[edit]- Council of Constantinople (861)

- Council of Constantinople (867)

- Council of Constantinople (869-870)

- Schism of 863

Sources

[edit]- ^ Norwich, John Julius (1997). A Short History of Byzantium. New York City, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. p. 142.

- ^ Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 451.

- ^ a b c d e f Duong, Brian (2024). The Filioque: Answering the Eastern Orthodox. Virginia, USA. p. 147.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Curta, Florian (2019). Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages. Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke. pp. 197–198.

- ^ Siecienski, A. Edward (2020). "Contra Latinos Et Adversus Graecos", Byzantium and the Papacy from the Fifth to Fifteenth Centuries Stage Two: The Jurisdictional Disputes (9th-11th Centuries). Bondgenotenlaan: Peeters Publishers. p. 14.

- Carr, John C. Fighting Emperors of Byzantium. 133-141. Pen and Sword Military an imprint of Pen and Sword Books Ltd., 2015

- Chadwick, Henry. East and West : The Making of a Rift in the Church : From Apostolic Times until the Council of Florence. Oxford ; Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Curta, Florian. Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages. Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke, 2019. 197-206.

- Dvornik, Francis (1948). The Photian Schism: History and Legend. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Duong, Brian. The Filioque: Answering the Eastern Orthodox. Virginia, USA: Brian Duong, 2024.

- Kaldellis, Anthony. The New Roman Empire : A History of Byzantium. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2024.

- Norwich, John Julius. A Short History of Byzantium. New York City, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc, 1997.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Siecienski, A. Edward. Contra Latino Et Adversus Graecos. Edited by A. Bucossi and A. Calia, 13-17.

- Peeters Publishers, Bondgenotenlaan, 2020

- Treadgold, Warren. A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1997.

External links

[edit]- The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, 1991.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Ignatius of Constantinople". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Ignatius of Constantinople". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.