Pan (god)

| Pan | |

|---|---|

God of nature, the wild, shepherds, flocks, and mountain wilds[1] | |

| |

| Abode | Arcadia |

| Symbol | Pan flute, goat |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Hermes and a daughter of Dryops, or Penelope |

| Consort | Syrinx, Echo, Pitys |

| Children | Silenus, Iynx, Krotos, Xanthus (out of Twelve) |

| Equivalents | |

| Roman | Faunus Inuus |

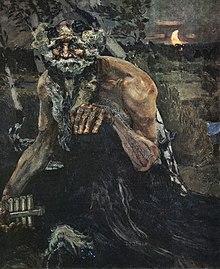

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Pan (/pæn/;[2] Ancient Greek: Πάν, romanized: Pán) is the god of the wild, shepherds and flocks, rustic music and impromptus, and companion of the nymphs.[3] He has the hindquarters, legs, and horns of a goat, in the same manner as a faun or satyr. With his homeland in rustic Arcadia, he is also recognized as the god of fields, groves, wooded glens, and often affiliated with sex; because of this, Pan is connected to fertility and the season of spring.[1]

In Roman religion and myth, Pan was frequently identified with Faunus, a nature god who was the father of Bona Dea, sometimes identified as Fauna; he was also closely associated with Silvanus, due to their similar relationships with woodlands, and Inuus, a vaguely-defined deity also sometimes identified with Faunus.[4][5][6] In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Pan became a significant figure in the Romantic movement of Western Europe and also in the twentieth-century Neopagan movement.[7]

Origins

[edit]Many modern scholars consider Pan to be derived from the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European god *Péh₂usōn, whom they believe to have been an important pastoral deity[8] (*Péh₂usōn shares an origin with the modern English word "pasture").[9] The Rigvedic psychopomp god Pushan (from PIE zero grade *Ph₂usōn) is believed to be a cognate of Pan. The connection between Pan and Pushan, both of whom are associated with goats, was first identified in 1924 by the German scholar Hermann Collitz.[10][11] The familiar form of the name Pan is contracted from earlier Πάων, derived from the root *peh₂- (guard, watch over).[12] According to Edwin L. Brown, the name Pan is probably a cognate with the Greek word ὀπάων "companion".[13]

In his earliest appearance in literature, Pindar's Pythian Ode iii. 78, Pan is associated with a mother goddess, perhaps Rhea or Cybele; Pindar refers to maidens worshipping Cybele and Pan near the poet's house in Boeotia.[14]

Worship

[edit]The worship of Pan began in Arcadia which was always the principal seat of his worship. Arcadia was a district of mountain people, culturally separated from other Greeks. Arcadian hunters used to scourge the statue of the god if they had been disappointed in the chase.[15]

Being a rustic god, Pan was not worshipped in temples or other built edifices, but in natural settings, usually caves or grottoes such as the one on the north slope of the Acropolis of Athens. These are often referred to as the Cave of Pan. The only exceptions are the Temple of Pan on the Neda River gorge in the southwestern Peloponnese – the ruins of which survive to this day – and the Temple of Pan at Apollonopolis Magna in ancient Egypt.[16] In the fourth century BC Pan was depicted on the coinage of Pantikapaion.[17]

Archaeologists, while excavating a Byzantine church of around 400 AD in Banyas, discovered in the walls of the church an altar of the god Pan with a Greek inscription, dating back to the second or third century AD. The inscription reads, "Atheneon son of Sosipatros of Antioch is dedicating the altar to the god Pan Heliopolitanus. He built the altar using his own personal money in fulfillment of a vow he made."[18]

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Greek religion |

|---|

|

In the mystery cults of the highly syncretic Hellenistic era,[19] Pan is identified with Phanes/Protogonos, Zeus, Dionysus and Eros.[20]

Epithets

[edit]

- Aegocerus (Ancient Greek: Αἰγόκερως, romanized: Aigókerōs, lit. 'goat-horned') was an epithet of Pan descriptive of his figure with the horns of a goat.[21]

- Lyterius (Ancient Greek: Λυτήριος), meaning Deliverer. There was a sanctuary at Troezen, and he had this epithet because he was believed during a plague to have revealed in dreams the proper remedy against the disease.[22]

- Maenalius (Ancient Greek: Μαινάλιος) or Maenalides (Ancient Greek: Μαιναλιδης), derived from mount Maenalus which was sacred to the god.[23]

Parentage

[edit]

Numerous different parentages are given for Pan by different authors.[25] According to the Homeric Hymn to Pan, he is the child of Hermes and an (unnamed) daughter of Dryops.[26] Several authors state that Pan is the son of Hermes and "Penelope", apparently Penelope, the wife of Odysseus:[27] according to Herodotus, this was the version which was believed by the Greeks,[28] and later sources such as Cicero and Hyginus call Pan the son of Mercury and Penelope.[29] In some early sources such as Pindar (c. 518 – c. 438 BC) and Hecataeus (c. 550 – c. 476 BC), he is called the child of Penelope by Apollo.[30] Apollodorus records two distinct divinities named Pan; one who was the son of Hermes and Penelope, and the other who had Zeus and a nymph named Hybris for his parents, and was the mentor of Apollo.[31] Pausanias records the story that Penelope had in fact been unfaithful to her husband, who banished her to Mantineia upon his return.[32] Other sources (Duris of Samos; the Vergilian commentator Servius) report that Penelope slept with all 108 suitors in Odysseus' absence, and gave birth to Pan as a result.[33] This myth reflects the folk etymology that equates Pan's name (Πάν) with the Greek word for "all" (πᾶν).[34] According to Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, Apollodorus has his parents as Hermes and Oeneis, while scholia on Theocritus have Aether and Oeneis.[35]

Like other nature spirits, Pan appears to be older than the Olympians, if it is true that he gave Artemis her hunting dogs and taught the secret of prophecy to Apollo. Pan might be multiplied as the Pans (Burkert 1985, III.3.2; Ruck and Staples, 1994, p. 132[36]) or the Paniskoi. Kerenyi (p. 174) notes from scholia that Aeschylus in Rhesus distinguished between two Pans, one the son of Zeus and twin of Arcas, and one a son of Cronus. "In the retinue of Dionysos, or in depictions of wild landscapes, there appeared not only a great Pan, but also little Pans, Paniskoi, who played the same part as the Satyrs".

Herodotus wrote that according to Egyptian chronology, Pan was the most ancient of the gods; but according to the version in which Pan was the son of Hermes and Penelope, he was born only eight hundred years before Herodotus, and thus after the Trojan war.[i] Herodotus concluded that that would be when the Greeks first learnt the name of Pan.[37]

Mythology

[edit]

Battle with Typhon

[edit]

The goat-god Aegipan was nurtured by Amalthea with the infant Zeus in Crete. In Zeus' battle with Typhon, Aegipan and Hermes stole back Zeus' "sinews" that Typhon had hidden away in the Corycian Cave.[38] Pan aided his foster-brother in the battle with the Titans by letting out a horrible screech and scattering them in terror. According to some traditions, Aegipan was the son of Pan, rather than his father. The constellation Capricornus is traditionally depicted as a sea-goat, a goat with a fish's tail (see "Goatlike" Aigaion called Briareos, one of the Hecatonchires). A myth reported as "Egyptian" in Hyginus's Poetic Astronomy[39] (which would seem[to whom?] to be invented to justify a connection of Pan with Capricorn)[citation needed] says that when Aegipan—that is Pan in his goat-god aspect[40]—was attacked by the monster Typhon, he dived into the river Nile; the parts above the water remained a goat, but those under the water transformed into a fish.

Erotic aspects

[edit]Pan is famous for his sexual prowess and is often depicted with a phallus. Diogenes of Sinope, speaking in jest, related a myth of Pan learning masturbation from his father, Hermes, and teaching the habit to shepherds.[41]

There was a legend that Pan seduced the moon goddess Selene, deceiving her with a sheep's fleece.[42]

One of the famous myths of Pan involves the origin of his pan flute, fashioned from lengths of hollow reed. Syrinx was a lovely wood-nymph of Arcadia, daughter of Ladon, the river-god. As she was returning from the hunt one day, Pan met her. To escape from his importunities, the fair nymph ran away and didn't stop to hear his compliments. He pursued from Mount Lycaeum until she came to her sisters who immediately changed her into a reed. When the air blew through the reeds, it produced a plaintive melody. The god, still infatuated, took some of the reeds, because he could not identify which reed she became, and cut seven pieces (or according to some versions, nine), joined them side by side in gradually decreasing lengths, and formed the musical instrument bearing the name of his beloved Syrinx. Henceforth, Pan was seldom seen without it.

Echo was a nymph who was a great singer and dancer and scorned the love of any man. This angered Pan, a lecherous god, and he instructed his followers to kill her. Echo was torn to pieces and spread all over Earth. The goddess of the Earth, Gaia, received the pieces of Echo, whose voice remains repeating the last words of others. In some versions, Echo and Pan had two children: Iambe and Iynx. In other versions, Pan had fallen in love with Echo, but she scorned the love of any man but was enraptured by Narcissus. As Echo was cursed by Hera to only be able to repeat words that had been said by someone else, she could not speak for herself. She followed Narcissus to a pool, where he fell in love with his own reflection and changed into a narcissus flower. Echo wasted away, but her voice could still be heard in caves and other such similar places.

Pan also loved a nymph named Pitys, who was turned into a pine tree to escape him.[43] In another version, Pan and the north wind god Boreas clashed over the lovely Pitys. Boreas uprooted all the trees to impress her, but Pan laughed and Pitys chose him. Boreas then chased her and threw her off a cliff resulting in her death. Gaia pitied Pitys and turned her into a pine tree.[44]

According to some traditions, Pan taught Daphnis, a rustic son of Hermes, how to play the pan-pipes, and also fell in love with him.[45][46]

Women who had had sexual relations with several men were referred to as "Pan girls."[47]

Panic

[edit]Disturbed in his secluded afternoon naps, Pan's angry shout inspired panic (panikon deima) in lonely places.[48][49] Following the Titans' assault on Olympus, Pan claimed credit for the victory of the gods because he had frightened the attackers. In the Battle of Marathon (490 BC), it is said that Pan favored the Athenians and so inspired panic in the hearts of their enemies, the Persians.[50]

Music

[edit]

In two late Roman sources, Hyginus[51] and Ovid,[52] Pan is substituted for the satyr Marsyas in the theme of a musical competition (agon), and the punishment by flaying is omitted.

Pan once had the audacity to compare his music with that of Apollo, and to challenge Apollo, the god of the lyre, to a trial of skill. Tmolus, the mountain-god, was chosen to judge. Pan blew on his pipes and gave great satisfaction with his rustic melody to himself and to his faithful follower, Midas, who happened to be present. Then Apollo struck the strings of his lyre. Tmolus at once awarded the victory to Apollo, and all but Midas agreed with the judgment. Midas dissented and questioned the justice of the award. Apollo would not suffer such a depraved pair of ears any longer and turned Midas' ears into those of a donkey.[53]

All of the Pans

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2021) |

Pan could be multiplied into a swarm of Pans, and even be given individual names, as in Nonnus' Dionysiaca, where the god Pan had twelve sons that helped Dionysus in his war against the Indians. Their names were Kelaineus, Argennon, Aigikoros, Eugeneios, Omester, Daphoenus, Phobos, Philamnos, Xanthos, Glaukos, Argos, and Phorbas.

Two other Pans were Agreus and Nomios. Both were the sons of Hermes, Agreus' mother being the nymph Sose, a prophetess: he inherited his mother's gift of prophecy, and was also a skilled hunter. Nomios' mother was Penelope (not the same as the wife of Odysseus). He was an excellent shepherd, seducer of nymphs, and musician upon the shepherd's pipes. Most of the mythological stories about Pan are actually about Nomios, not the god Pan. Although, Agreus and Nomios could have been two different aspects of the prime Pan, reflecting his dual nature as both a wise prophet and a lustful beast.

Aegipan, literally "goat-Pan," was a Pan who was fully goatlike, rather than half-goat and half-man. When the Olympians fled from the monstrous giant Typhoeus and hid themselves in animal form, Aegipan assumed the form of a fish-tailed goat. Later he came to the aid of Zeus in his battle with Typhoeus, by stealing back Zeus' stolen sinews. As a reward the king of the gods placed him amongst the stars as the Constellation Capricorn. The mother of Aegipan, Aix (the goat), was perhaps associated with the constellation Capra.

Sybarios was an Italian Pan who was worshipped in the Greek colony of Sybaris in Italy. The Sybarite Pan was conceived when a Sybarite shepherd boy named Krathis copulated with a pretty she-goat amongst his herds.

"The great god Pan is dead"

[edit]

In Pseudo-Plutarch's De defectu oraculorum ("The Obsolescence of Oracles"),[54] Pan is the only Greek god who actually dies. During the reign of Tiberius (AD 14–37), the news of Pan's death came to one Thamus, a sailor on his way to Italy by way of the Greek island of Paxi. A divine voice hailed him across the salt water, "Thamus, are you there? When you reach Palodes,[55] take care to proclaim that the great god Pan is dead." Which Thamus did, and the news was greeted from shore with groans and laments.

Christian apologists, including Eusebius of Caesarea, have long made much of Plutarch's story of the death of Pan. Due to the word "all" in Greek also being "pan," a pun was made that "all demons" had perished.[56]

In Rabelais' Fourth Book of Pantagruel (sixteenth century), the Giant Pantagruel, after recollecting the tale as told by Plutarch, opines that the announcement was actually about the death of Jesus Christ, which did take place at about the same time (towards the end of Tiberius' reign), noting the aptness of the name: "for he may lawfully be said in the Greek tongue to be Pan, since he is our all. For all that we are, all that we live, all that we have, all that we hope, is him, by him, from him, and in him."[57] In this interpretation, Rabelais was following Guillaume Postel in his De orbis terrae concordia.[58]

The nineteenth-century visionary Anne Catherine Emmerich, in a twist echoed nowhere else, claims that the phrase "the Great Pan" was actually a demonic epithet for Jesus Christ, and that "Thamus, or Tramus" was a watchman in the port of Nicaea, who, at the time of the other spectacular events surrounding Christ's death, was then commissioned to spread this message, which was later garbled "in repetition."[59]

In modern times, G. K. Chesterton has repeated and amplified the significance of the "death" of Pan, suggesting that with the "death" of Pan came the advent of theology. To this effect, Chesterton claimed, "It is said truly in a sense that Pan died because Christ was born. It is almost as true in another sense that men knew that Christ was born because Pan was already dead. A void was made by the vanishing world of the whole mythology of mankind, which would have asphyxiated like a vacuum if it had not been filled with theology."[60][61][62] It was interpreted with concurrent meanings in all four modes of medieval exegesis: literally as historical fact, and allegorically as the death of the ancient order at the coming of the new.[original research?]

In more modern times, some have suggested a possible naturalistic explanation for the myth. For example, Robert Graves (The Greek Myths) reported a suggestion that had been made by Salomon Reinach[63] and expanded by James S. Van Teslaar[64] that the sailors actually heard the excited shouts of the worshipers of Tammuz, Θαμούς πανμέγας τέθνηκε (Thamoús panmégas téthnēke, "All-great Tammuz is dead!"), and misinterpreted them as a message directed to an Egyptian sailor named 'Thamus': "Great Pan is Dead!" Van Teslaar explains, "[i]n its true form the phrase would have probably carried no meaning to those on board who must have been unfamiliar with the worship of Tammuz which was a transplanted, and for those parts, therefore, an exotic custom."[65] Certainly, when Pausanias toured Greece about a century after Plutarch, he found Pan's shrines, sacred caves and sacred mountains still very much frequented. However, a naturalistic explanation might not be needed. For example, William Hansen[66] has shown that the story is quite similar to a class of widely known tales known as Fairies Send a Message.

The cry "The Great Pan is dead" has appealed to poets, such as John Milton, in his ecstatic celebration of Christian peace, On the Morning of Christ's Nativity line 89,[67] Elizabeth Barrett Browning,[68] and Louisa May Alcott.[69]

Influence

[edit]Iconography

[edit]Representations of Pan have influenced conventional popular depictions of the Devil. [70]

Literary revival

[edit]

In the late-eighteenth century, interest in Pan revived among liberal scholars. Richard Payne Knight discussed Pan in his Discourse on the Worship of Priapus (1786) as a symbol of creation expressed through sexuality. "Pan is represented pouring water upon the organ of generation; that is, invigorating the active creative power by the prolific element."[71]

John Keats's "Endymion" (1818) opens with a festival dedicated to Pan where a stanzaic hymn is sung in praise of him. Keats drew most of his account of Pan's activities from the Elizabethan poets. Douglas Bush notes, "The goat-god, the tutelary divinity of shepherds, had long been allegorized on various levels, from Christ to 'Universall Nature' (Sandys); here he becomes the symbol of the romantic imagination, of supra-mortal knowledge.'"[72]

In the late-nineteenth century Pan became an increasingly common figure in literature and art. Patricia Merivale states that between 1890 and 1926 there was an "astonishing resurgence of interest in the Pan motif".[73] He appears in poetry, in novels and children's books, and is referenced in the name of the character Peter Pan.[74] In the Peter Pan stories, Peter represents a golden age of pre-civilisation in both the minds of very young children (before enculturation and education), and in the natural world outside the influence of humans. Peter Pan's character is both charming and selfish - emphasizing our cultural confusion about whether human instincts are natural and good, or uncivilised and bad. J. M. Barrie describes Peter as 'a betwixt and between', part animal and part human, and uses this device to explore many issues of human and animal psychology within the Peter Pan stories.[75]

Arthur Machen's 1894 novella The Great God Pan uses the god's name in a simile about the whole world being revealed as it really is: "seeing the Great God Pan". The novella is considered by many (including Stephen King) as being one of the greatest horror-stories ever written.[76]

In an article in Hellebore magazine, Melissa Edmundson argues that women writers from the nineteenth century used the figure of Pan "to reclaim agency in texts that explored female empowerment and sexual liberation". In Eleanor Farjeon's poem "Pan-Worship", the speaker tries to summon Pan to life after feeling "a craving in me", wishing for a "spring-tide" that will replace the stagnant "autumn" of the soul. A dark version of Pan's seductiveness appears in Margery Lawrence's Robin's Rath, both giving and taking life and vitality.

Pan is the eponymous "Piper at the Gates of Dawn" in the seventh chapter of Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows (1908). Grahame's Pan, unnamed but clearly recognisable, is a powerful but secretive nature-god, protector of animals, who casts a spell of forgetfulness on all those he helps. He makes a brief appearance to help Rat and Mole recover the Otter's lost son Portly.

The goat-footed god entices villagers to listen to his pipes as if in a trance in Lord Dunsany's novel The Blessing of Pan (1927). Although the god does not appear within the story, his energy invokes the younger folk of the village to revel in the summer twilight, while the vicar of the village is the only person worried about the revival of worship of the old pagan god.

Pan features as a prominent character in Tom Robbins' Jitterbug Perfume (1984).

The British writer and editor Mark Beech of Egaeus Press published in 2015 the limited-edition anthology Soliloquy for Pan[77] which includes essays and poems such as "The Rebirthing of Pan" by Adrian Eckersley, "Pan's Pipes" by Robert Louis Stevenson, "Pan with Us" by Robert Frost, and "The Death of Pan" by Lord Dunsany. Some of the detailed illustrated depictions of Pan included in the volume are by the artists Giorgio Ghisi, Sir James Thornhill, Bernard Picart, Agostino Veneziano, Vincenzo Cartari, and Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.

In the Percy Jackson novels, author Rick Riordan uses "The Great God Pan is dead" quote as a plot point in the novel The Sea of Monsters, and in The Battle of the Labyrinth Pan is revealed to be in a state of half-death.

Revival in music

[edit]Pan inspired pieces of classical music by Claude Debussy. Syrinx, written as part of incidental music to the play Psyché by Gabriel Mourey, was originally called "Flûte de Pan". Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune was based on a poem by Stéphane Mallarmé.

The story of Pan is the inspiration for the first movement in Benjamin Britten's work for solo oboe, Six Metamorphoses after Ovid first performed in 1951. Inspired by characters from Ovid's fifteen-volume work Metamorphoses, Britten titled the movement, "Pan: who played upon the reed pipe which was Syrinx, his beloved."

The British rock band Pink Floyd named its first album The Piper at the Gates of Dawn in reference to Pan as he appears in The Wind in the Willows. Andrew King, Pink Floyd's manager, said Syd Barrett "thought Pan had given him an understanding into the way nature works. It formed into his holistic view of the world."[78]

Brian Jones, a founding member of The Rolling Stones, strongly identified with Pan.[78] He produced the live album Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka, about a Moroccan festival that evoked the ancient Roman rites of Pan.

Musician Mike Scott of the Waterboys refers to Pan as an archetypal force within us all, and talks about his search for “The Pan Within", a theme also reflected in the song’s sequel, “The Return of Pan".[79]

Revived worship

[edit]In the English town of Painswick in Gloucestershire, a group of eighteenth-century gentry, led by Benjamin Hyett, organised an annual procession dedicated to Pan, during which a statue of the deity was held aloft, and people shouted "Highgates! Highgates!" Hyett also erected temples and follies to Pan in the gardens of his house and a "Pan's lodge", located over Painswick Valley. The tradition died out in the 1830s, but was revived in 1885 by a new vicar, W. H. Seddon, who mistakenly believed that the festival had been ancient in origin. One of Seddon's successors, however, was less appreciative of the pagan festival and put an end to it in 1950, when he had Pan's statue buried.[80]

Occultists Aleister Crowley and Victor Neuburg built an altar to Pan on Da'leh Addin, a mountain in Algeria, where they performed a magic ceremony to summon the god. In the final rite of the 1910 ritual play The Rites of Eleusis, written by Crowley, Pan "pulls back the final veil, revealing the child Horus, who represents humanity's eternal and divine element.[79]"

Neopaganism

[edit]In 1933, the Egyptologist Margaret Murray published the book The God of the Witches, in which she theorised that Pan was merely one form of a horned god who was worshipped across Europe by a witch-cult.[81] This theory influenced the Neopagan notion of the Horned God, as an archetype of male virility and sexuality. In Wicca, the archetype of the Horned God is highly important, as represented by such deities as the Celtic Cernunnos, the Hindu Pashupati, and the Greek Pan.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Herodotus was born about 485 BC, so by his reckoning Pan would have been born around 1285—earlier than the Trojan War as estimated by most of the Greek antiquarians, and a century before the date reckoned by Eratosthenes.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Neto, F. T. L.; Bach, P. V.; Lyra, R. J. L.; Borges Junior, J. C.; Maia, G. T. d. S.; Araujo, L. C. N.; Lima, S. V. C. (2019). "Gods associated with male fertility and virility". Andrology. 7 (3): 267–272. doi:10.1111/andr.12599. PMID 30786174. S2CID 73507440.

- ^ "Pan" (Greek mythology) entry in Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ Edwin L. Brown, "The Lycidas of Theocritus Idyll 7", Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, 1981:59–100.

- ^ Schmitz, Leonhard (1849). "Pan". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. III. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 106, 107.

- ^ Morford, Mark P. O.; Lenardon, Robert J. (1985) [1971]. Classical Mythology (third ed.). New York and London: Longman. pp. 476, 477.

- ^ Grant, Michael (1984) [1971]. Roman Myths. New York: Dorset Press.

- ^ The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft, Hutton, Ronald, chapter 3

- ^ Mallory, J. P.; Adams, D. Q. (2006). The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 434. ISBN 978-0-19-929668-2.

- ^ "*pa-". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ H. Collitz, "Wodan, Hermes und Pushan," Festskrift tillägnad Hugo Pipping pȧ hans sextioȧrsdag den 5 November 1924 1924, pp 574–587.

- ^ R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 1149.

- ^ West, M. L. (24 May 2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. OUP Oxford. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-19-928075-9.

- ^ Edwin L. Brown, "The Divine Name 'Pan'", Transactions of the American Philological Association 107 (1977:57–61), notes (p. 59) that the first inscription mentioning Pan is a sixth-century dedication to ΠΑΟΝΙ, a "still uncontracted" form.

- ^ The Extant Odes of Pindar at Project Gutenberg. See note 5 to Pythian Ode III, "For Heiron of Syracuse, Winner in the Horse-race."

- ^ Theocritus. vii. 107

- ^ Horbury, William (1992). Jewish Inscriptions of Graeco-Roman Egypt. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-521-41870-6.

- ^ Sear, David R. (1978). Greek Coins and Their Values . Volume I: Europe (pp. 168–169). Seaby Ltd., London. ISBN 0 900652 46 2

- ^ Altar to Greek god found in wall of Byzantine church raises questions

- ^ Eliade, Mircea (1982) A History of Religious Ideas Vol. 2. University of Chicago Press. § 205.

- ^ In the second-century "Hieronyman Theogony', which harmonized Orphic themes from the theogony of Protogonos with Stoicism, he is Protogonos, Phanes, Zeus and Pan; in the Orphic Rhapsodies he is additionally called Metis, Eros, Erikepaios and Bromios. The inclusion of Pan seems to be a Hellenic syncretization (West, M. L. (1983) The Orphic Poems. Oxford:Oxford University Press. p. 205).

- ^ Lucan, ix. 536; Lucretius, v. 614.

- ^ A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, Lyterius

- ^ A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, Maenalius

- ^ "Regenboog. Nr.1 Verluid". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Hard, p. 215: "accounts of his parentage vary greatly"; Gantz, p. 110: "his parentage was quite disputed".

- ^ Gantz, p. 110; Hard, p. 215; Homeric Hymn to Pan (19), 34–9.

- ^ Hard, p. 215; March, p. 582. According to Hard, the idea of Penelope being the mother "is so odd that it is tempting to suppose that this Penelope was not originally the wife of Odysseus, but an entirely different figure, perhaps an Arcadian nymph or the above-mentioned daughter of Dryops".

- ^ Hard, p. 215–6; Herodotus, 2.145.

- ^ Cicero, De Natura Deorum 3.22.56 (pp. 340, 341); Hyginus, Fabulae 224.

- ^ Gantz, p. 110; Pindar, fr. 90 Bowra; FGrHist 1 F371 [= Scholia on Lucan's Pharsalia, 3.402.110.25].

- ^ Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.4.1, E.7.38.

- ^ Pausanias, 8.12.5.

- ^ Frazer, p. 305 n. 1.

- ^ The Homeric Hymn to Pan provides the earliest example of this wordplay, suggesting that Pan's name was born from the fact that he delighted "all" the gods.

- ^ Smith, William, ed. (1867). Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. Vol. III. Boston. p. 106. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Pan "even boasted that he had slept with every maenad that ever was—to facilitate that extraordinary feat, he could be multiplied into a whole brotherhood of Pans."

- ^ Herodotus, Histories II.145

- ^ "In this story Hermes is clearly out of place. He was one of the youngest sons of Zeus and was brought into the story only because... he was a master/thief. The real participant in the story was Aigipan: the god Pan, that is to say. in his quality of a goat (aix). (Kerenyi, p. 28). Kerenyi points out that Python of Delphi had a son Aix (Plutarch, Moralia 293c) and detects a note of kinship betrayal.

- ^ Hyginus, Poetic Astronomy 2.18: see Theony Condos, Star Myths of the Greeks and Romans 1997:72.

- ^ Kerenyi, p. 95.

- ^ Dio Chrysostom, Discourses, vi. 20.

- ^ Hard, p. 46; Gantz, p. 36; Kerenyi, pp. 175, 196; Grimal, s.v. Selene; Virgil, Georgics 3.391–93 has Pan capturing and deceiving Luna with the gift of a fleece; Servius, Commentary on the Georgics of Vergil 391 ascribes to the Greek poet Nicander an earlier account that Pan wrapped himself in a fleece to disguise himself as a sheep.

- ^ Smith s.v. Pitys

- ^ Libanius, Progymnasmata, 1.4

- ^ Cohen, pp 169-170

- ^ Also testified by Clement in Homilies 5.16. Clement, a Christian pope, was trying to discredit pagans and their beliefs in his works, however other finds seem to support this particular claim.

- ^ Lane Fox, Robin (1988). Pagans and Christians. London: Penguin Books. p. 130. ISBN 0-14-009737-6.

- ^ "Pan (mythology) – Discussion and Encyclopedia Article. Who is Pan (mythology)? What is Pan (mythology)? Where is Pan (mythology)? Definition of Pan (mythology). Meaning of Pan (mythology)". Knowledgerush.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ Robert Graves,The Greek Myths, p.101

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 662–663.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae, 191 (on-line source).

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses, 11.146ff (on-line source).

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses XI: 146-194

- ^ Moralia, 5:17; Ogilvie, R. M. (1967). "The Date of the 'De Defectu Oraculorum'", Phoenix, 21(2), 108–119.

- ^ "Where or what was Palodes?" Archived 16 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Lane Fox, Robin (1988). Pagans and Christians. London: Penguin Books. p. 130. ISBN 0-14-009737-6.

- ^ François Rabelais, Fourth Book of Pantagruel (Le Quart Livre), Chap. 28 [1].

- ^ Guillaume Postel, De orbis terrae concordia, Book 1, Chapter 7.

- ^ Emmerich, Anne Catherine (2006). The Life of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, volume IV. Charlotte, NC: Saint Benedict Press. p. 309. ISBN 9781905574131. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ Chesterton, G. K. (1925). "Chapter VIII. The End of the World". The Everlasting Man. Hodder & Stoughton. Part I. On the Creature Called Man – via CCEL.

- ^ The Collected Works of G.K. Chesterton II. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. 1986. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-89870-116-6.

- ^ Orthodoxy. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. 2004. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-486-43701-9.

- ^ Reinach, in Bulletin des correspondents helleniques 31 (1907:5–19), noted by Van Teslaar.

- ^ Van Teslaar, "The Death of Pan: a classical instance of verbal misinterpretation", The Psychoanalytic Review 8 (1921:180–83).

- ^ Van Teslaar 1921:180.

- ^ William Hansen (2002) "Ariadne's thread: A guide to international tales found in classical literature" Cornell University Press. pp.133–136

- ^ Kathleen M. Swaim, "'Mighty Pan': Tradition and an Image in Milton's Nativity 'Hymn'", Studies in Philology 68.4 (October 1971:484–495)..

- ^ See Corinne Davies, "Two of Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Pan poems and their after-life in Robert Browning's 'Pan and Luna'", Victorian Poetry 44,.4, (Winter 2006:561–569).

- ^ Alcott, Louisa May (September 1863). "Thoreau's Flute" (PDF). The Atlantic Monthly: 280–281.

- ^

Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1987) [1977]. "Evil in the Classical World". The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity. Cornell paperbacks (reprint ed.). Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 125, 126. ISBN 9780801494093. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

The iconography of Pan and the Devil [...] coalesce: cloven hooves, goat's legs, horns, beast's ears, saturnine face, and goatee. [...] The iconographic influence of Pan upon the Devil is enormous.

- ^ Payne-Knight, R. Discourse on the Worship of Priapus, 1786, p.73

- ^ Barnard, John. John Keats : The Complete Poems, p. 587, ISBN 978-0-14-042210-8.

- ^ Merivale, Patricia. Pan the Goat-God: his Myth in Modern Times, Harvard University Press, 1969, p.vii.

- ^ Lurie, Alison (2003). Afterword in Peter Pan. Signet. p. 198. ISBN 9780451520883.

- ^ Ridley, Rosalind (2016). Peter Pan and the Mind of J M Barrie. UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-9107-3.

- ^ The Great God Pan by Arthur Machen. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Beech, Mark (2015). Soliloquy for Pan (Illustrated. First ed. limited to 300 copies ed.). UK: Egaeuspress. pp. 350 pp. ISBN 978-0-957160682.

- ^ a b Soar, Katy (2022). "The Piper at the Gates of Dawn". Hellebore. 8 (The Unveiling Issue): 10–19.

- ^ a b Soar, Katy (2020). "The Great Pan in Albion". Hellebore. 2 (The Wild Gods Issue): 14–27.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald. The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft pp 161–162.

- ^ Hutton, Robert (1999). The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820744-3.

Sources

[edit]- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1921. ISBN 0-674-99135-4. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Borgeaud, Philippe (1979). Recherches sur le Dieu Pan. Geneva University.

- Bowra, Cecil Maurice, Pindari carmina: cum fragmentis, Oxford, E. Typographeo Clarendoniano, 1947. Internet Archive.

- Burkert, Walter (1985). Greek Religion. Harvard University Press.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius, De Natura Deorum in Cicero: On the Nature of the Gods. Academics, translated by H. Rackham, Loeb Classical Library No. 268, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, first published 1933, revised 1951. ISBN 978-0-674-99296-2. Online version at Harvard University Press. Internet Archive.

- Cohen, Beth (22 November 2021). Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill Publications. ISBN 978-90-04-11618-4.

- Diotima (2007), The Goat Foot God, Bibliotheca Alexandrina.

- Hard, Robin, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology", Psychology Press, 2004, ISBN 9780415186360. Google Books.

- Herodotus, Histories, translated by A. D. Godley, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1920. ISBN 0674991338. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homeric Hymn 19 to Pan, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, Fabulae, in The Myths of Hyginus, edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960. Online version at ToposText.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Grimal, Pierre, The Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996. ISBN 978-0-631-20102-1.

- Kerényi, Károly (1951). The Gods of the Greeks. Thames & Hudson.

- Laurie, Allison, "Afterword" in Peter Pan, J. M. Barrie, Signet Classic, 1987. ISBN 978-0-451-52088-3.

- Malini, Roberto (1998), Pan dio della selva, Edizioni dell'Ambrosino, Milano.

- March, Jenny, Cassell's Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Cassell & Co., 2001. ISBN 0-304-35788-X. Internet Archive.

- Ruck, Carl A. P.; Danny Staples (1994). The World of Classical Myth. Carolina Academic Press. ISBN 0-89089-575-9.

- Servius, Commentary on the Georgics of Vergil, Georgius Thilo, Ed. 1881. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library (Latin).

- Virgil, Georgics in Bucolics, Aeneid, and Georgics of Vergil. J. B. Greenough. Boston. Ginn & Co. 1900. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Vinci, Leo (1993), Pan: Great God of Nature, Neptune Press, London.

External links

[edit]- Pan (god)

- Animal gods

- Arts gods

- Horned gods

- Greek love and lust gods

- Musicians in Greek mythology

- Mythological caprids

- Nature gods

- Pastoral gods

- Fertility gods

- Children of Hermes

- Children of Zeus

- Oracular gods

- Sexuality in ancient Rome

- Sexuality in ancient Greece

- Flautists

- Greek gods

- LGBTQ themes in Greek mythology

- Satyrs

- Mountain gods

- Religion in ancient Arcadia

- Music and singing gods

- Consorts of Selene

- Shapeshifters in Greek mythology