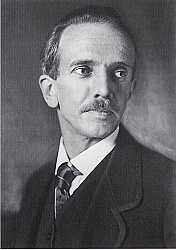

Otto Bartning

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (October 2014) |

Otto Bartning | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 12 April 1883 Karlsruhe |

| Died | 20 February 1959 (aged 75) Darmstadt |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | Königliche Technische Hochschule, Berlin |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Projects | Bauhaus and Bauhochschule |

Otto Bartning (12 April 1883 in Karlsruhe – 20 February 1959 in Darmstadt) was a Modernist German architect, architectural theorist and teacher. In his early career he developed plans with Walter Gropius for the establishment of the Bauhaus. He was a member of Der Ring. In 1951, he was elected president of the Federation of German Architects.

Early career

[edit]Bartning was the son of Otto Bartning, from Mecklenburg, a merchant in Mazatlán, Mexico, and Hamburg. After completing his Abitur in 1902 in Karlsruhe, Bartning enrolled in the winter semester at the Königliche Technische Hochschule in Berlin (the forerunner of today's Technische Universität). He set off for an 18-month world tour in March 1904 (older sources incorrectly claim this journey was from 1902 to 1903), after which he settled down to complete his studies in Berlin and Karlsruhe. At the same time as studying, he began to establish a practice as an architect in Berlin from 1905. Bartning left his studies without graduating in either 1907 or 1908 (the sources do not agree).

In 1910, Bartning built his first church in Germany for the Old Lutheran parish (now SELK) in Essen - Moltkeviertel, and subsequently designed the nearby circular Auferstehungskirche / Church of the Resurrection (built in 1929), which is one of the most important models for modern Protestant church construction in Central Europe.

Bartning became known as an early reformer of art and design education after the First World War together with his friend, Walter Gropius, among others. In 1918, he planned with Gropius the concept and contributed to the programme for the Bauhaus. He influenced Gropius' 1919 avant-garde Bauhaus manifesto with its workshop principles and openness to the latest international influences. His ideas for the Bauhochschule in 1926 were developments on the same theme.

"The Other Bauhaus"

[edit]Following the closure of the Bauhaus, the government of Thuringia invited Otto Bartning to become director of a replacement school in Weimar, the Staatliche Bauhochschule (Building High School), sited in the Henry van de Velde building. The new school, often known as "The Other Bauhaus", sought to combine traditional academic teaching methods with those of the Bauhaus in an attempt to integrate craft and design. However, the original Bauhaus was more modernist in approach, while the new school was more pragmatic and craft based. Students were encouraged to participate in real projects and to market their designs commercially. In 1927, for example, the weaving department produced material for the German Pavilion at the Milan Fair, designed by Otto Bartning's architectural office.

From 1929 to 1931, Bartning was one of six leading modernist architects and members of Der Ring to contribute to the Siemensstadt housing project. And in 1932 Bartning published his influential scheme for the interior of a prefabricated house.

Later career

[edit]Bartning's attempt to steer a rational middle way failed with the increasing politicisation of the arts in the 1930s. His writings in the magazine Die Volkswohnungen ('People's Housing') appear among polemics advocating land reform and a craft-based self-sufficient Germany.

In 1930, shortly after a National Socialist and conservative government coalition won power in Thuringia, Bartning resigned. Many of the 14 professors and lecturers at The Other Bauhaus continued their careers in Germany during the war; for example Ernst Neufert worked under Albert Speer and went on to enjoy international success after the war. Bartning, on the other hand, retreated into church architecture between 1933 and 1948, and was later awarded honorary doctorates, including RIBA honorary membership, and held important posts as architect and advisor.

Sources

[edit]Dawson, Layla, The Architectural Review, 2 Jan 1997

External links

[edit]- Otto Bartning in German Wikipedia

- Website of the Otto Bartning Arbeitsgemeinschaft Kirchenbau OBAK (= Otto Bartning Association on Church Construction)