Mir Osman Ali Khan

| Sir Mir Osman Ali Khan GCSI GBE | |

|---|---|

| Nizam of Hyderabad Amir al-Muminin | |

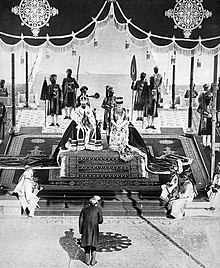

Mir Osman Ali Khan in 1926 | |

| Nizam of Hyderabad | |

| Reign | 29 August 1911 – 17 September 1948 Titular: 17 September 1948 – 24 February 1967[1] |

| Coronation | 18 September 1911[2] |

| Predecessor | Mahbub Ali Khan, Asaf Jah VI |

| Successor | Title abolished Barkat Ali Khan, Asaf Jah VIII (titular) |

| Prime minister | See list

|

| Born | 5 April 1886[3] or 6 April 1886 Purani Haveli, Hyderabad City, Hyderabad State, British India (now in Telangana, India) |

| Died | 24 February 1967 (aged 80) King Kothi Palace, Kingdom of Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh (now in Telangana), India |

| Burial | Judi Mosque, (opposite King Kothi Palace), Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India (now in Telangana, India) |

| Spouse |

Azam-un-Nisa Begum

(m. 1906; died 1955)Shahzada Begum Ikbal Begum Gowhar Begum Mazhar-un-Nisa Begum

(m. 1923; died 1964)Leila Begum Jani Begum |

| Issue Among others | Azam Jah Moazzam Jah |

| House | Asaf Jahi dynasty |

| Father | Mahbub Ali Khan, Asaf Jah VI |

| Mother | Amat-uz-Zahra Begum |

| Religion | Sunni Islam[4] |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | Hyderabad State Forces |

| Years of service | 1911 - 1948 |

| Battles / wars | |

Mir Osman Ali Khan, Asaf Jah VII (5[5] or 6 April 1886 – 24 February 1967)[6] was the last Nizam[7] (ruler) of Hyderabad State, the largest state in the erstwhile Indian Empire. He ascended the throne on 29 August 1911, at the age of 25[8] and ruled the State of Hyderabad between 1911 and 1948, until the Indian Union annexed it.[9] He was styled as His Exalted Highness (H.E.H) the Nizam of Hyderabad,[10] and was widely considered one of the world's wealthiest people of all time.[11] With some estimates placing his wealth at 2% of U.S. GDP,[11] his portrait was on the cover of Time magazine in 1937.[12] As a semi-autonomous monarch, he had his mint, printing his currency, the Hyderabadi rupee, and had a private treasury that was said to contain £100 million in gold and silver bullion, and a further £400 million of jewels (in 2008 terms).[11] The major source of his wealth was the Golconda mines, the only supplier of diamonds in the world at that time.[13][14][15] Among them was the Jacob Diamond, valued at some £50 million (in 2008 terms),[16][17][18] and used by the Nizam as a paperweight.[19]

During his 37-year rule, electricity was introduced, and railways, roads, and airports were developed. He was known as the "Architect of modern Hyderabad" and is credited with establishing many public institutions in the city of Hyderabad, including Osmania University, Osmania General Hospital, State Bank of Hyderabad,[20] Begumpet Airport, and the Hyderabad High Court. Two reservoirs, Osman Sagar and Himayat Sagar, were built during his reign, to prevent another great flood in the city. The Nizam also constructed the Nizam Sagar Dam and, in 1923, a reservoir constructed across the Manjira River, a tributary of the Godavari River, between Achampet(Nizamabad) and Banjepally villages of the Kamareddy district in Telangana, India. It is located at about 144 km (89 mi) northwest of Hyderabad. Nizam Sagar is the oldest dam in the state of Telangana.[21]

The Nizam had refused to accede Hyderabad to India after the country's independence on 15 August 1947. He wanted his domains to remain an independent state or join Pakistan.[22] Later, he wanted his state to join India; however, his power had weakened because of the Telangana Rebellion and the rise of a radical militia known as the Razakars, whom he could not put down. In 1948, the Indian Army invaded and annexed Hyderabad State and defeated the Razakars.[23] The Nizam became the Rajpramukh of Hyderabad State between 1950 and 1956, after which the state was partitioned and became part of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Maharashtra.[24][25]

In 1951, he not only started the construction of Nizam Orthopedic Hospital (now known as Nizam's Institute of Medical Sciences (NIMS)) and gave it to the government on a 99-year lease for a monthly rent of Rs.1,[26] he also donated 14,000 acres (5,700 ha) of land from his estate to Vinobha Bhave's Bhoodan movement for re-distribution among landless farmers.[8][27]

Early life

[edit]Mir Osman Ali Khan was born 5[5] or 6 April 1886, the second son of Mahboob Ali Khan, Asaf Jah VI and Amat-uz-Zahra Begum[28][29] at Purani Haveli (also known as Masarrat Mahal palace). He was educated privately and reportedly became fluent in Urdu, Persian, Arabic and English.[30][31][5] Under Nawab Muhammad Ali Beg he received court ethics and military training.[32]

On the recommendation of the Viceroy of India, Lord Elgin in 1898, in early 1899 Sir Brian Egerton (of the Egerton family and former tutor to Maharajah of Bikaner Ganga Singh) was appointed as Mir Osman Ali Khan's English tutor for two years.[3] During this period he lived away from the principal palace. He lived on his own to avoid the atmosphere of the palace quarters under the guidance of Sir Brian and other British officials and mentors so that he could flourish as a gentleman of the highest class. Sir Brian Egerton recorded that as a child, Mir Osman Ali Khan was magnanimous and "anxious to learn". Because of the indomitable attitude of zenana (the women) who were determined to send Mir Osman Ali Khan out of Hyderabad for further studies, he pursued them at Mayo College after consultation with the principal nobles of the Paigah family.[32][33]

Reign

[edit]

Mir Mahboob Ali Khan The VI Nizam died on 29 August 1911 and on the same day Mir Osman Ali Khan was proclaimed Nizam VII under the supervision of Nawab Shahab Jung, a minister of Police and Public works.[34] On 18 September 1911, the crowning ceremony was officially held at the Chowmahalla Palace.

His coronation Durbar (court) included the prime minister of Hyderabad Maharaja Kishen Pershad, Colonel Alexander Pinhey (1911–1916) British resident of Hyderabad, the Paigah, and the distinguished nobles of the state and the head of principalities under Nizam domain.[3][32][35]

The famous mines of Golconda were the major source of wealth for the Nizams,[36] with the Kingdom of Hyderabad being the only supplier of diamonds for the global market in the 18th century.[36]

Mir Osman Ali Khan acceded as the Nizam of Hyderabad upon the death of his father in 1911. The state of Hyderabad was the largest of the princely states in colonial India. With an area of 86,000 square miles (223,000 km2), it was roughly the size of the present-day United Kingdom. The Nizam was the highest-ranking prince in India, was one of only five princes entitled to a 21-gun salute, held the unique title of "Nizam", and titled "His Exalted Highness" and "Faithful Ally of the British Crown".[37]

Early years (1911 to 1918)

[edit]In 1908, three years before the Nizam's coronation, the city of Hyderabad was struck by a major flood that resulted in the death of thousands. The Nizam, on the advice of Sir M. Visvesvaraya, ordered the construction of two large reservoirs—the Osman Sagar and Himayat Sagar—to prevent another flood.[38]

He was given the title of "Faithful Ally of the British Crown" after World War One because of his financial contribution to the British Empire's war effort.[39] Part of the reason behind his unique title of "His Exalted Highness" and other titles was due to the huge amounts of financial help that he provided the British amounting to nearly £25 million (£1,538,279,000 in 2025).[39] (For example, No. 110 Squadron RAF's original complement of Airco DH.9A aircraft were Osman Ali's gift. Each aircraft bore an inscription to that effect, and the unit became known as the "Hyderabad Squadron".)[40] He also paid for a Royal Navy vessel, the N-class destroyer, HMAS Nizam commissioned in 1940 and transferred to the Royal Australian Navy.[41]

In 1918, the Nizam issued a firman (decree) that established Osmania University, the first university to have Urdu as the language of instruction. The present campus was completed in 1934. The Firman also mentioned the university's detailed mission and objectives.[42] The establishment of Osmania University was highly lauded by Nobel Prize laureate Rabindranath Tagore who was overjoyed to see the day when Indians are "freed from the shackles of a foreign language and our education becomes naturally accessible to all our people".[39]

Post-World War (1918 to 1939)

[edit]

In 1919, the Nizam ordered the formation of the Executive Council of Hyderabad, presided over by Sir Sayyid Ali Imam, including eight other members, each in charge of one or more departments. The president of the Executive Council would also be the prime minister of Hyderabad.[citation needed]

The Begumpet Airport was established in 1930 with the eventual formation of Hyderabad Aero Club by the Nizam in 1936. Initially, Nizam's private airline, Deccan Airways, one of the earliest airlines in British India, used it as a domestic and international airport. The terminal building was constructed in 1937.[43] The first commercial flight took off from the airport in 1946.[44]

Final years of his reign (1939 to 1948)

[edit]

The Nizam arranged a matrimonial alliance with the deposed caliph Abdulmejid II whereby Nizam's first son Azam Jah would marry Princess Durrushehvar of the Ottoman Empire. It was believed that the matrimonial alliance between Nizam and Abdulmejid II would lead to the emergence of a Muslim ruler who could be acceptable to the world powers in place of the Ottoman Sultans. After India's Independence, the Nizam attempted to declare his sovereignty over the state of Hyderabad, either as a protectorate of the British Empire or as a sovereign monarchy. However, his power weakened because of the Telangana Rebellion and the rise of the Razakars, a Muslim militia who wanted Hyderabad to remain under Muslim rule. In 1948, India invaded and annexed Hyderabad State, and the rule of the Nizam ended. He became the Rajpramukh and served from 26 January 1950 to 31 October 1956.[45]

Contributions to society

[edit]Educational initiatives

[edit]By donating to major educational institutions throughout India, he introduced many educational reforms during his reign. Up to 11% of his budget was spent on education.[46] Schools, colleges and a Department for Translation were set up. Primary education was made compulsory and provided free for the poor.

Osmania University

[edit]He founded the Osmania University in 1918 through a royal firman.[47] It is one of the largest universities in India. Schools, colleges and a Department for Translation were set up.[48]

Construction of major public buildings

[edit]Nearly all the major public buildings and institutions in Hyderabad city, such as the Hyderabad High Court, Jubilee Hall,[49] Nizamia Observatory, Moazzam Jahi Market, Kachiguda Railway Station, Asafiya Library (State Central Library, Hyderabad), the Town Hall now known as the Assembly Hall, Hyderabad Museum now known as the State Museum; hospitals like Osmania General Hospital, Nizamia Hospital and many other buildings were constructed under his reign.[50][51][52] He also built the Hyderabad House in Delhi, now used for diplomatic meetings by the Government of India.[53][54]

Establishment of Hyderabad State Bank

[edit]In 1941, he started his bank, the Hyderabad State Bank. It was later renamed State Bank of Hyderabad and merged with the State Bank of India as the state's central bank in 2017. It was established on 8 August 1941 under the Hyderabad State Bank Act. The bank managed the Osmania Sicca (Hyderabadi rupee), the currency of the state of Hyderabad. It was the only state in India that had its currency, and the only state in British India where the ruler was allowed to issue currency. In 1953, the bank absorbed, by merger, the Mercantile Bank of Hyderabad, which Raja Pannalal Pitti had founded in 1935.[55][need quotation to verify]

In 1956, the Reserve Bank of India took over the bank as its first subsidiary and renamed it State Bank of Hyderabad (SBH). The Subsidiary Banks Act was passed in 1959. On 1 October 1959, SBH and the other banks of the princely states became subsidiaries of SBI. It merged with SBI on 31 March 2017.[56]

Flood prevention

[edit]After the Great Musi Flood of 1908, which killed an estimated 50,000 people, the Nizam constructed two lakes to prevent flooding—the Osman Sagar and Himayat Sagar[21][57] named after himself, and his son Azam Jah respectively.[58]

Agricultural reforms

[edit]The Nizam founded agricultural research in the Marathwada region of Hyderabad State with the establishment of the Main Experimental Farm in 1918 in Parbhani. During his rule, agricultural education was available only at Hyderabad; crop research centres for sorghum, cotton, and fruits existed in Parbhani. After independence, the Indian government developed this facility further and renamed it Marathwada Agriculture University on 18 May 1972.[59]

Contribution to Indian aviation

[edit]India's first airport—the Begumpet Airport—was established in the 1930s with the formation of the Hyderabad Aero Club by the Nizam. Initially, it was used as a domestic and international airport by Deccan Airways Limited, the first airline in British India. The airport terminal was constructed in 1937.[60]

Philanthropy

[edit]Donations to Hindu temples

[edit]During Mir Osman Ali Khan’s regime, financial support of Rs 97,000 and more than Two-lakh-acres of land were donated for the Hindu temples. Hindu temple histories in Hyderabad, both oral and written, feature close interaction with the Nizam’s court and administration.[61]

The Nizam donated Rs. 82,825 to the Yadagirigutta temple at Bhongir, Rs. 29,999 to the Sita Ramachandraswamy temple, Bhadrachalam[62] and yearly donation of Rs. 8,000 to the Tirupati Balaji Temple.[63]

He also donated Rs. 50,000 towards the reconstruction of Sitarambagh temple located in the old city of Hyderabad,[62] and bestowed a grant of 100,000 Hyderabadi rupees towards the reconstruction of Thousand Pillar Temple.[64]

He also donated 1,525 acres of Land to "Sita Rama Swami Temple" located in Devaryamjal[65]

Other temples which received yearly monetary grants were Yadgirigutta temple, Mahetta Balekdas temple, Sikhar temple, Seetharambagh temple and Jamsingh temple.[61]

Restoration of Ramappa temple

[edit]The 7th Nizam also donated towards restoration of Ramappa Temple which is now declared a heritage site by UNESCO.[66][67]

Donation towards golden temple

[edit]After hearing about the Golden Temple of Amritsar through Maharaja Ranjit Singh,[68][69] he started providing it with yearly grants.[70][71]

Donation towards the compilation of Holy Mahabharata

[edit]In 1932, there was a need for money for the publication of the Holy Mahabharata by the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute located in Pune. A formal request was made to Mir Osman Ali Khan who granted Rs. 1000 per year for 11 years.[72]

He also gave Rs 50,000 for the construction of the institute's guest house[73] which stands today as the Nizam Guest House.[74][75]

Donation in Gold to the National Defence Fund

[edit]

In October 1962, during the Sino-Indian War, the PM Lal Bahadur Shastri visited Hyderabad and requested the Nizam to contribute to the National Defence Fund, set up in the wake of the Indo-Chinese skirmishes.[76][77] In response, the Nizam donated 5,000 Kilos of gold to the Indian army. In terms of today's gold price in the international market, this donation translates to Rs 2,500 Crore.[78][79][80]

Donations to educational institutions

[edit]The Nizam donated Rs 1 million for the Banaras Hindu University,[81][82] Rs. 500,000 for the Aligarh Muslim University,[83] and 300,000 for the Indian Institute of Science.[81]

He also made large donations to many institutions in India and abroad with special emphasis given to educational institutions such as the Jamia Nizamia and the Darul Uloom Deoband.[84][85]

Shri Shivaji Educational Society Amravati also received a total grant of 50,000 from the Nizam in the 1940's.[86]

Restoration of Ajanta Ellora caves

[edit]During the early 1920s, the site of Ajanta Caves was under the princely state of the Hyderabad[87] and Osman Ali Khan (the Nizam of Hyderabad) appointed experts to restore the artwork, converted the site into a museum and built a road to enable tourists to come to the site.[87][88][89]

The Nizam's Director of Archaeology obtained the services of two experts from Italy, Professor Lorenzo Cecconi, assisted by Count Orsini, to restore the paintings in the caves. The Director of Archaeology for the last Nizam of Hyderabad said of the work of Cecconi and Orsini:

The repairs to the caves and the cleaning and conservation of the frescoes have been carried out on such sound principles and in such a scientific manner that these matchless monuments have found a fresh lease of life for at least a couple of centuries.[90]

Donations to Palestine

[edit]The Nizam provided substantial funding for the restoration of Masjid Al-Aqsa (one of the three holiest sites in the Islamic world). Additionally, he contributed greatly to the creation of waqfs (Muslim endowments) in Palestine and supported the renovation and restoration of a hospice named Zawiyah Hindiyya.[91][92]

Firman to ban public cow slaughter

[edit]In 1922, Nizam VII issued a firman banning the public slaughter of cows in his kingdom.[93] [94]

Operation Polo and abdication

[edit]

After Indian independence in 1947, the country was partitioned into India and Pakistan. The princely states were left free to make whatever arrangement they wished with either India or Pakistan. The Nizam ruled over more than 16 million people and 82,698 square miles (214,190 km2) of territory when the British withdrew from the sub-continent in 1947.[95] But unlike the other princely states, the Nizam refused to sign the instrument of accession. Instead he opted to sign a 1-year standstill agreement agreed upon by the British, and signed by then viceroy Lord Mountbatten.[96] The Nizam refused to join either India or Pakistan, preferring to form a separate independent kingdom within the British Commonwealth of Nations.[95]

This proposal for independence was rejected by the British government, but the Nizam continued to explore it. Towards this end, he kept up open negotiations with the Government of India regarding the modalities of a future relationship while opening covert negotiations with Pakistan in a similar vein. The Nizam cited the Razakars as evidence that the people of the state were opposed to any agreement with India.[citation needed]

The one-year standstill agreement turned out to be a severe blow to Nizam as it gave all foreign affairs, communication and defence power to the Indian government. The new Indian government wasn't happy that a sovereign state would exist right at the centre of India.[97] In accordance to this, they ultimately decided to invade Hyderabad in 1948, in operation code-named Operation Polo. Under the supervision of Major General Jayanto Nath Chaudhuri, one division of the Indian Army and a tank brigade invaded and captured Hyderabad.[98] The annexation was over in just 109 hours or roughly 4 days. Due to no foreign connections and no real defence, the war was a losing cause for Hyderabad from the start. After the annexation the territory came under Indian rule and the Nizam was removed from his position but allowed to keep all personal wealth and title.[99]

Wealth

[edit]The Nizam was so wealthy that he was portrayed on the cover of Time magazine on 22 February 1937, being described as the world's richest man.[100] At its peak, the wealth of Osman Ali Khan, Asaf Jah VII was worth ₹660 crore (US$77 million) (all his conceivable assets combined) in the early 1940s, while Nizam's entire treasure of jewels, would be worth between US$150 million and US$500 million variously in today's terms.[101][102][103][104] He used the Jacob Diamond, a 185-carat diamond that is part of the Nizam's jewellery, as a paperweight.[105] During his days as Nizam, he was reputed to be the richest man in the world, having a fortune estimated at US$2 billion in the early 1940s[106] (US$37.3 billion in 2023 dollars)[107] or two percent of the US economy then.[108]

The Nizam's personal fortune was estimated to be roughly £110 million, including £40 million in gold and jewels (equivalent to £2,690,199,336 in 2023).[109][110][111]

The Indian government still exhibits the jewellery as the Jewels of the Nizams of Hyderabad (now in Delhi). There are 173 jewels, which include emeralds weighing nearly 2,000 carats (0.40 kg), and pearls exceeding 40 thousand chows. The collection includes gemstones, turban ornaments, necklaces and pendants, belts and buckles, earrings, armbands, bangles and bracelets, anklets, cufflinks and buttons, watch chains, and rings, toe rings, and nose rings.[112]

Along with the Nizam's jewels, two Bari gold coins worth hundreds of crores were considered the rarest in the world. Himayat Ali Mirza has requested the central government to bring these coins, which were made in the Arabic script, back to Hyderabad.[113]

Gift to Queen Elizabeth II

[edit]In 1947, Nizam made a gift of diamond jewels, including a tiara and necklace, to the future Queen Elizabeth II on the occasion of her marriage. The brooches and necklace were still worn by the Queen until her death and the necklace is known as the Nizam of Hyderabad necklace.[114]

Personal life

[edit]

The Nizam lived at King Kothi Palace — bought from a nobleman (Kamal Khan, an architect of those times) — from age 13 until his death. He never moved to Chowmahalla Palace, even after his accession to the throne.[115]

Unlike his father, he was not interested in fine clothing or hunting. His hobbies rather included poetry and writing ghazals in Urdu.[116]

He revered his mother and visited her every day she was alive; he used to visit her grave almost every day after she died.[117]

Family

[edit]He had seven wives.[118] His first wife was Sahibzadi Azam-un-Nisa Begum Sahiba also known as Dulhan Pasha Begum. She was the elder daughter of Nawab Jahangir Jung. They married on 14 April 1906 at Eden Bagh, Hyderabad. Nawab Khudrath Nawaz Jung was his first brother-in-law.[3][119][120] She was the mother of his sons Azam Jah and Moazzam Jah,[121] and a daughter Ahmed-un-Nisa Begum also known as Shahzada Pasha.[122][123] She died in 1955, and was buried beside her husband in Masjid-e Judi.[124] Another wife was Shahzada Begum.[125] She was the mother of Hasham Jah. Her two children had died at birth, and Hasham Jah was her third child.[126] Another wife was Ikbal Begum.[127] She was the daughter of his Army Secretary, Nawab Nazir Jung.[128][129] Another wife was Gowhar Begum.[127] She was a niece of the Aga Khan.[129] Another wife was Mazhar-un-Nisa Begum.[130] She was the youngest daughter of Khurshid-ul-Mulk, the grand-daughter in the line of the fifth Nizam, Afzal-ud-Daulah, and a niece of the sixth Nizam, Mahboob Ali Khan. They married in 1923.[29] She died on 18 June 1964.[131] Another wife was Leila Begum.[130] She was a Hindu woman whose family willingly sent her to his harem as a gesture of gratitude. She possessed exceptional beauty, and was his favourite wife.[132] She had five sons Zulfiqar Jah, Bhojat Jah, Shabbir Jah, Nawazish Jah and Fazal Jah; and two daughters Mashhadi Begum and Sayeeda Begum.[133] His last wife was Jani Begum.[130] She was the daughter of Sahibzada Yavar Jung, and was the mother of Imdad Jah. She died on 7 June 1959.[134] In total, he had 34 children: 18 sons and 16 daughters.[135][136][137][138][139][140][141][142][143][144][145]

His first son Azam Jah married Durru Shehvar, (daughter of the Ottoman caliph Abdul Mejid II), while his second son Moazzam Jah married Niloufer, (a niece of the Ottoman sultan).[146][147]

Azam Jah and Durru Shehvar had two sons, Mukarram Jah and Muffakham Jah, with the former succeeding his grandfather as the de jure Nizam.[146]

His second son Moazzam Jah, after his divorce from Princess Nilofer, since she couldn't bear a child, married Razia Begum and had three daughters - Princess Fatima Fouzia, Princess Amina Merzia and Princess Oolia Kulsum. He also married Anwari Begum and had a son, Prince Shahmat Jah.[148]

Another socially prominent grandson is Mir Najaf Ali Khan, son of Hasham Jah,[149][150][151] who represents several trusts of the last Nizam, including the H.E.H. the Nizam's Charitable Trust and the Nizam Family Welfare Association.[150]

The Nizams' daughters had been married traditionally to young men of the House of Paigah. This family belonged to the Sunni sect.[152] One of his daughters Ahmed-un-Nisa Begum,[148] by his first wife Azam-un-Nisa Begum, was once engaged to a nawab, but the Nizam suddenly called off the wedding after a traveling holy man warned him that he would not live long after her marriage. She remained unmarried,[153] and died on 24 March 1985.[148] Another of his daughters was Basheer-un-Nisa Begum. She was born in September 1927. She married Nawab Kazim Jung, popularly known as Ali Pasha, and had one daughter. She died at her residence, Osman Cottage, in Purani Haveli, of natural causes on 28 July 2020, aged ninety-three. She was the last surviving child of the Nizam.[154][155] Another daughter Mashhadi Begum, by his wife Leila Begum, was born in September 1939.[156] In January 1959, she married Paigah noble Mahmood Jah,[153] and had four sons and two daughters. She died on 16 November 2015 due to chronic illness. Her funeral was performed at Masjid-e Judi, and she was buried at the Paigah Tombs, besides to her husband.[156] His youngest daughter by Leila Begum, Sayeeda Begum also known as Lily Pasha, was born on 30 December 1949. She died of a brief illness on 17 July 2017, and was buried in Masjid-e Judi. She was survived by a son and a daughter.[157] Some other daughters were Asmat-un-Nisa Begum, Hurmat-un-Nisa Begum,[158] Mehr-un-Nisa Begum[127] and Masood-un-Nisa Begum.[159]

Various parties have used Nizam's name for political gains. Another great-grandson, Himayat Ali Mirza wrote to the prime minister in this regard along with the Election Commission of India, requesting political parties not to use Nizam's name in today's politics as it is disrespectful to such a great personality.[39][160]

Final years and death

[edit]The Nizam continued to stay at the King Kothi Palace until his death. He used to issue firmans on inconsequential matters in his newspaper, the Nizam Gazette.[115]

He died on Friday, 24 February 1967. In his will, he asked to be buried in Masjid-e Judi, a mosque where his mother was buried, that faced King Kothi Palace.[161][162] The government declared state mourning on 25 February 1967, the day when he was buried. State government offices remained closed as a mark of respect while the National Flag of India was flown at half-mast on all the government buildings throughout the state.[163] The Nizam Museum documents state:

"The streets and pavements of the city were littered with the pieces of broken glass bangles as an incalculable number of women broke their bangles in mourning, which Telangana women usually do as per Indian customs on the death of a close relative."[164]

"The Nizam's funeral procession was the biggest non-religious, non-political meeting of people in the history of India till that date."

Millions of people of all religions from different parts of the state entered Hyderabad in trains, buses and on bullocks for a last glimpse of their king in a coffin in the King Kothi Palace Camp in Hyderabad.[165] The crowd was so uncontrollable that barricades were installed alongside the road to enable people to move in a queue.[166] D. Bhaskara Rao, chief curator, of the Nizam's Museum stated that an estimated one million people were part of the procession.[167]

Title and salutation

[edit]Salutation style

[edit]The Nizam was the honorary Colonel of the 20 Deccan Horse. In 1918, King George V elevated Nawab Mir Osman Ali Khan Siddiqi Bahadur from "His Highness" to "His Exalted Highness". In a letter dated 24 January 1918, the title "Faithful Ally of the British Government was conferred on him.[168][better source needed]

Full Titular Name

[edit]The titles during his life were:

1886–1911: Nawab Bahadur Mir Osman Ali Khan Siddiqi.

[168]

1911–1912: His Highness Rustam-i-Dauran, Arustu-i-Zaman, Wal Mamaluk, Asaf Jah VII, Muzaffar ul-Mamaluk, Nizam ul-Mulk, Nizam ud-Daula, Nawab Mir Sir Osman ‘Ali Khan Siddqi Bahadur, Sipah Salar, Fath Jang, Nizam of Hyderabad, GCSI

[168]

1912–1917: Colonel His Highness Rustam-i-Dauran, Arustu-i-Zaman, Wal Mamaluk, Asaf Jah VII, Muzaffar ul-Mamaluk, Nizam ul-Mulk, Nizam ud-Daula, Nawab Mir Sir Osman ‘Ali Khan Siddqi Bahadur, Sipah Salar, Fath Jang, Nizam of Hyderabad, GCSI

[168]

1917–1918: Colonel His Highness Rustam-i-Dauran, Arustu-i-Zaman, Wal Mamaluk, Asaf Jah VII, Muzaffar ul-Mamaluk, Nizam ul-Mulk, Nizam ud-Daula, Nawab Mir Sir Osman ‘Ali Khan Siddqi Bahadur, Sipah Salar, Fath Jang, Nizam of Hyderabad, GCSI, GBE

[168]

1918–1936: Lieutenant-General His Exalted Highness Rustam-i-Dauran, Arustu-i-Zaman, Wal Mamaluk, Asaf Jah VII, Muzaffar ul-Mamaluk, Nizam ul-Mulk, Nizam ud-Daula, Nawab Mir Sir Osman ‘Ali Khan Siddqi Bahadur, Sipah Salar, Fath Jang, Faithful Ally of the British Government, Nizam of Hyderabad, GCSI, GBE

[168]

1936–1941: Lieutenant-General His Exalted Highness Rustam-i-Dauran, Arustu-i-Zaman, Wal Mamaluk, Asaf Jah VII, Muzaffar ul-Mamaluk, Nizam ul-Mulk, Nizam ud-Daula, Nawab Mir Sir Osman ‘Ali Khan Siddqi Bahadur, Sipah Salar, Fath Jang, Faithful Ally of the British Government, Nizam of Hyderabad and Berar, GCSI, GBE

[168]

1941–1967: General His Exalted Highness Rustam-i-Dauran, Arustu-i-Zaman, Wal Mamaluk, Asaf Jah VII, Muzaffar ul-Mamaluk, Nizam ul-Mulk, Nizam ud-Daula, Nawab Mir Sir Osman ‘Ali Khan Siddqi Bahadur, Sipah Salar, Fath Jang, Faithful Ally of the British Government, Nizam of Hyderabad and Berar, GCSI, GBE.[168][169]

Honours and eponyms

[edit]- Recipient of the Delhi Durbar Gold Medal, 1911 as part of the 1911 Delhi Durbar Honours,[170][171]

- GCSI: Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India, 1911[172]

- GCStJ: Bailiff Grand Cross of the Order of St John, 1911[172]

- GBE: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire, 1917[172]

- Recipient of the King George V Silver Jubilee Medal, 1935[172]

- Recipient of the King George VI Coronation Medal, 1937[172]

- Recipient of the Royal Victorian Chain, 1946[172]

List of Eponyms

[edit]- Osmania General Hospital

- Osmania Biscuit

- Osman Sagar, a reservoir in Hyderabad

- Osmanabad

- The Nizam of Hyderabad necklace

- The Nizam Gate of Ajmer Sharif Dargah[173]

See also

[edit]- Establishments of the Nizams

- Hospitals established by the Nizams

- Nizam's Guaranteed State Railway

- Nizams of Hyderabad

- Asaf Jahi dynasty

- Hyderabad State

References

[edit]- ^ Ali, Mir Quadir (17 September 2019). "Hyderabad's tryst with history". Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

The question now is: What exactly happened on September 17, 1948? [...] The Nizam's radio broadcast meant the lifting of the house arrest of Government of India's Agent General K.M. Munshi, allowing him to work on a new government, with the Nizam as Head of State.

- ^ Benjamin B. Cohen, Kingship and Colonialism in India's Deccan, 1850–1948 (Macmillan, 2007) p81[need quotation to verify]

- ^ a b c d Jaganath, Santosh (2013). The History of Nizam's Railways System. Laxmi Book Publication. p. 44. ISBN 9781312496477. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ "No parallel to Hyderabad's Muharram procession in India". News18. news18. 24 November 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Jaganath, Santosh (2013). The History of Nizam's Railways System. Laxmi Book Publication. p. 44. ISBN 9781312496477. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ "Here are five super-rich people from the pages of history!". The Economic Times. 1 May 2015.

- ^ "Family of Indian royals wins £35m court battle against Pakistan". BBC News. 2 October 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ a b ":: The Seventh Nizam - The Nizam's Museum Hyderabad, Telangana, India". thenizamsmuseum.com. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ "This day, that year: How Hyderabad became a part of the union of India". 16 September 2018. Archived from the original on 30 December 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ "HYDERABAD: Silver Jubilee Durbar". Time. 22 February 1937. Archived from the original on 24 May 2007. Retrieved 20 May 2007.

- ^ a b c Zupan, M.A. (2017). Inside Job: How Government Insiders Subvert the Public Interest. Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–115. ISBN 978-1-107-15373-8. LCCN 2016044124.

- ^ "The Nizam of Hyderabad". Time. Archived from the original on 6 March 2005.

- ^ Jhala, A.D. (2015). Royal Patronage, Power and Aesthetics in Princely India. Empires in Perspective. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-31656-5.

- ^ "Globalisation of Golconda".

- ^ "Making money the royal way!". Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ McCaffrey, Julie (3 February 2012). "Exclusive: The last Nizam of Hyderabad was so rich he had a £50 million diamond paperweight". Mirror.co.uk. London.

- ^ Bedi, Rahul (12 April 2008). "India finally settles £1million Nizam dispute". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Exhibitions at National Museum of India, New Delhi(India)". 2 April 2009. Archived from the original on 2 April 2009.

- ^ Shah, Tahir. "Alan the Red, the Brit who makes Bill Gates a pauper." Times Online. The Sunday Times. 7 October 2007. Web. 19 9ay 2010.

- ^ Pagdi, Raghavendra Rao (1987) Short History of Banking in Hyderabad District, 1879-1950. In M. Radhakrishna Sarma, K.D. Abhyankar, and V.G. Bilolikar, eds. History of Hyderabad District, 1879-1950AD (Yugabda 4981-5052). (Hyderabad : Bharatiya Itihasa Sankalana Samiti), Vol. 2, pp.85-87.

- ^ a b "Nature Discovery in Telangana :: Telangana Tourism". telanganatourism.gov. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ "Why wealth of Hyderabad Nizam's heirs depends on Pakistan". NDTV.com. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ Apparasu, Srinivasa Rao (16 September 2022). "How Hyd merger with Union unfolded". Hindustan Times.

- ^ "A Memorable Republic Day". pib.nic.in. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ Karnataka State Gazetteer: Gulbarga. Director of Printing, Stationery and Publications at the Government Press. 1966. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ "The Last Nizam who put Hyderabad on global map". Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ Sunil, Mungara (4 September 2016). "Much of Bhoodan land found to be under encroachment in city | Hyderabad News". The Times of India. TNN / Updated.

- ^ Yazdani, Z.; Chrystal, M. (1985). The Seventh Nizam: The Fallen Empire. author. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-9510819-0-7.

- ^ a b Bawa, B.K. (1992). The Last Nizam: The Life and Times of Mir Osman Ali Khan. Viking. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-670-83997-1.

- ^ IFTHEKHAR, J. S. (13 February 2012). "Nizam's generous side and love for books". The Hindu. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ "Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society". Pakistan Historical Society. 46. the University of Michigan: 3–4(104). 1998. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ a b c "Chapter II" (PDF). Shodh Ganga-Indian Electronic Thesises and Dissertations. p. 56. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ Keen, Caroline (2003). The power behind the throne: Relations between the British and the Indian states 1870-1909 (PDF) (PhD thesis). SOAS University of London. pp. 84–86. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2020.

- ^ "Delhi Durbar of 1911: All you wanted to know !". The Heritage Lab. 17 December 2020.

- ^ T, Uma (April 2003). "1". Accession of Hyderabad state to the Indian union: a study of the political and pressure groups (1945-1948) (PhD thesis). Department of History, School of Social Sciences, University of Hyderabad. p. 20. hdl:10603/1882. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2020 – via Shodh Ganga-Indian Electronic Thesises and Dissertations.

- ^ a b "Celebrating the Nizam's fabled Golconda diamonds". Economic Times Blog. 23 February 2019. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ "'His Exalted Highness' to be staged today". The Hindu. 14 March 2007. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ Law 1914, p. 85-92.

- ^ a b c d Zompa, Tenzin (6 April 2021). "Mir Osman Ali Khan, Hyderabad Nizam who wore cotton pyjamas & used a diamond as paper weight". ThePrint. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ "RAF – Bomber Command No.110 Squadron". raf.mod.uk. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ "HMAS Nizam". Royal Australian Navy. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ "Osmania University". osmania.ac.in. Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ "Begumpet Airport History". Archived from the original on 21 December 2005.

- ^ "Begumpet Airport". Archived from the original on 19 October 2021.

- ^ "Fact Check: The Nizam of Hyderabad never fled Hyderabad". India Today. 29 January 2019. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ "Nizam Hyderabad Mir Osman Ali Khan was a perfect secular ruler". The Siasat Daily - Archive. 13 August 2015. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ "Osmania University". osmania.ac.in. Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ "Welcome to Osmania University". Osmania.ac.in. 26 April 1917. Archived from the original on 12 August 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ Aleem, Shamim; Aleem, M. A. (1984). Developments in Administration Under H.E.H. the Nizam VII. Osmania University Press.

- ^ Lasania, Yunus Y. (26 April 2017). "100 years of Osmania University, the hub of Telangana agitation". Mint. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ "Once the pride of the Nizam, Hyderabad's iconic Osmania hospital now lies in shambles". The News Minute. 24 January 2017. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ "Kacheguda station scripts 100 years of history". The Hans India. 3 June 2016. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ Nayar, K.P. (18 July 2011). "Ties too big for Delhi table – Space dilemma mirrors growth in Indo-US relationship". The Telegraph. Kolkota. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ Sharma, Manoj (8 June 2011). "Of princes, palaces and plush points". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 10 October 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ Pagdi, Raghavendra Rao (1987) Short History of Banking in Hyderabad District, 1879–1950. In M. Radhakrishna Sarma, K.D. Abhyankar, and V.G. Bilolikar, eds. History of Hyderabad District, 1879-1950AD (Yugabda 4981–5052). (Hyderabad: Bharatiya Itihasa Sankalana Samiti), Vol. 2, pp.85–87.

- ^ Sridhar, G. Naga (8 April 2014). "Ethnic flavour: SBH to be chief banker to new Telangana state". BusinessLine. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ "Gandipet's Osman Sagar Lake, Hyderabad". exploretelangana.com. 24 August 2013. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ "Himayat Sagar Lake – Weekend Tourist Spot of Hyderabad". exploretelangana.com. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ "MAU". mkv. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ Venkateshwarlu, K. (26 May 2001). "A tome on the aviation history of the Deccan". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ a b Today, Telangana (27 July 2022). "The progressive rule of Nizams". Telangana Today. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ a b "A 'miser' who donated generously". 20 September 2010. Archived from the original on 5 February 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ^ "Nizam gave funding for temples, and Hindu educational institutions". 28 May 2013. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ "Attempt to portray Nizam as 'intolerant oppressor' decried". Gulf News. 16 September 2014. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ "Devaryamjal temple land case: Officials examine Nizam-era Pahanis". 22 May 2021.

- ^ "Ramappa temple's first renovation effort was taken up in 1914". The Times of India. 26 July 2021.

- ^ Ahmed, Mohammed Hussain (27 July 2021). "UNESCO mentions Nizam's role in restoration of Ramappa Temple". The Siasat Daily – Archive.

- ^ "Maharaja Ranjit Singh's contributions to Harimandir Sahib". Archived from the original on 17 April 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ "A Brief History of The Nizams of Hyderabad". Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ Jaganath, Dr Santosh. The History of Nizam's Railways System. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781312496477. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ Morgan, Diane (2007). From Satan's Crown to the Holy Grail: Emeralds in Myth, Magic, and History. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275991234. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ "Family members rue that Hyderabad has forgotten the last Nizam's contribution to the city". 18 August 2016. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "Nizam's Guest House, Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune". Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "Reminiscing the seventh Nizam's enormous contribution to education". telanganatoday. 27 March 2017. Archived from the original on 26 August 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "Over Year On, Bori's Historic Nizam Guest House Still Awaits Reopening". 14 November 2011. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ Bureau, Our (12 September 2014). "When the miserly Nizam became munificent". www.thehansindia.com.

{{cite news}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ "When Osman Ali Khan donated 5 tonnes of gold to Govt. of India". Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ Nanisetti, Serish (11 November 2018). "The truth about the Nizam and his gold". The Hindu.

- ^ Elliot, Sir Henry Miers (1849). Bibliographical Index to the Historians of Muhammedan India. J. Thomas.

- ^ Hashmi, Syed Ali (2017). Hyderabad 1948 : an avoidable invasion. New Delhi. ISBN 9788172210793. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Nizam gave funding for temples, and Hindu educational institutions". missiontelangana. 28 May 2013. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ "Nizam gave funding for temples, Hindu educational institutions". siasat. 10 September 2010. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ "Nothing is more disgraceful for a nation than to throw into the oblivion its historical heritage and the works of its ancestors". 12 April 2016. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ "Mir Osman Ali Khan: Richest Indian to ever exist in documented history". The Siasat Daily - Archive. 30 March 2018. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ "NISAB AHLE KHIDMAT-E-SHARIA(Syllabus for Observers of Islamic Law)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ "Shri Shivaji Education Society Amravati". ssesa.org.

- ^ a b Cohen, Richard S. (2006). Beyond Enlightenment: Buddhism, Religion, Modernity. Routledge. pp. 51–58. ISBN 978-1-134-19205-2.

- ^ Jain, Madhu. "Cave paintings of Ajanta and Ellora become a tragic monument to archaeological neglect post-independence". India Today.

- ^ Abraham, Sarah (2 August 2022). "Ajanta and Ellora Caves - Monuments - UcL Places". UncrushedLeaves.

- ^ "Ajanta cave paintings of Nizam era lie in a state of neglect". 8 July 2018.

- ^ Mohammed, Syed (21 October 2023). "Hyderabad's history of support and solidarity with Palestine". The Hindu.

- ^ "Welcome to Representative Office of India, Ramallah, Palestine".

- ^ "Islamic scholars dissuade slaughter of cows on Bakrid". The Times of India. 11 August 2019.

- ^ "Why every political party will seek to resurrect Nizam in Hyderabad today". The Times of India. 17 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Lessons to learn from Hyderabad's past". The Times of India. 15 December 2013. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ Trumbull, Robert (23 October 1947). "BIG INDIAN STATE KEEPS SOVEREIGNTY; Hyderabad Makes Standstill Agreement With Dominion, Holding Status for Year". The New York Times.

- ^ Nanisetti, Serish (15 September 2018). "Accession of Hyderabad: When a battle by cables forced Nizam's hand". The Hindu.

- ^ "Exclusive sunder lal report on Indian armies annexation of Hyderabad and the following mass killings of Muslims". 30 November 2013. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ Nanisetti, Serish (15 September 2018). "Accession of Hyderabad: When a battle by cables forced Nizam's hand". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ "Time Magazine Cover: The Nizam of Hyderabad – Feb. 22, 1937". Time. Archived from the original on 17 June 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ "INDIA: The Nizam's Daughter". Time. 19 January 1959. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009.

- ^ "Exhibition of jewels of Hyderabad Nizams includes fifth-largest diamond in world". 3 September 2001.

- ^ "rediff.com: Hyderabad museum to exhibit Nizam's jewels".

- ^ "Priceless Nizam jewels to be exhibited". The Times of India. 20 August 2001.

- ^ Y. Lasania, Yunus. "The last Nizam of Hyderabad was not a miser". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "INDIA: The Nizam's Daughter". Time. 19 January 1959. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- ^ Foreign Commerce Weekly. Vol. 24. U.S. Department of Commerce. 1946. p. 25.

- ^ "Here are five super-rich people from the pages of history!". The Economic Times. 1 May 2015. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "Gifts of gold to help the Indian treasury". The Times. 14 December 1965.[need quotation to verify]

- ^ Krishnan, Usha Ramamrutham Bala; Ramamrutham, Bharath (2001). Jewels of the Nizams. Department of Culture, Government of India. ISBN 978-81-85832-15-9. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ Methil Renuka (3 September 2001). "Exhibition of jewels of Hyderabad Nizams includes fifth-largest diamond in world". India Today. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ "Clipping of Sakshi Telugu Daily - Hyderabad Constituencies". epaper.sakshi.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ "The Nizam of Hyderabad Rose Brooches and Necklace". From Her Majesty's Jewel Vault. 11 February 2013. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ a b Khalidi, Omar (2009). A Guide to Architecture in Hyderabad, Deccan, India (PDF). p. 163. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ "A visual ode to Mir Osman Ali Khan, the architect of modern". The Times of India. 8 April 2018. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ ":: The Seventh Nizam - the Nizam's Museum Hyderabad, Telangana, India". Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ Ikegame, A. (2013). Princely India Re-imagined: A Historical Anthropology of Mysore from 1799 to the present. Routledge/Edinburgh South Asian Studies Series. Taylor & Francis. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-136-23909-0.

- ^ Khan, Mir Ayoob Ali (23 September 2013). "Nizam paid 128 kg in gold coins as meher to first wife". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ Jaganath, S. The History of Nizam's Railways System. Lulu.com. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-312-49647-7.

- ^ Sharma, P.L. (1980). India Betrayed. Red-Rose Publications. p. 87.

- ^ "Nizam's Family Tree". Internet Archive. 6 October 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ Link: Indian Newsmagazine. 1978. p. 18.

- ^ "Masjid-i Judi". Dome Home. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ M, Hymavathi (22 June 2021). "Khada Dupatta: A timeless ensemble". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Akbar, Syed (28 March 2018). "Nizam's grandson seeks recognition from government for all heirs of royal family". The Times of India. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Krishnan, U.R.B.; Ramamrutham, B. (2001). Jewels of the Nizams. Department of Culture, Government of India. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-7508-306-6.

- ^ "Hyderabad Rulers with their Coinage details". Chiefa Coins. 15 August 1947. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ a b Bawa, B.K. (1992). The Last Nizam: The Life and Times of Mir Osman Ali Khan. Viking. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-670-83997-1.

- ^ a b c Company Law Institute of India (1991). The Income Tax Reports. Company Law Institute of India. pp. 234, 237.

- ^ Company Law Institute of India (1986). The Income Tax Reports. Company Law Institute of India. p. 263.

- ^ Hasan, M. (2022). Pakistan in an Age of Turbulence. Pen & Sword Books. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-5267-8861-0.

- ^ Khan, Mir Ayoob Ali (19 February 2018). "Last surviving son of Nizam, Fazal Jah, dies". The Times of India. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ Taxation. "Taxation House". 1975. p. 230.

- ^ Nanisetti, Serish (6 October 2019). "Who gets to own the Nizam's millions?". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 27 March 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Webb, Philippa (2016). Robert McCorquodale; Jean-Pierre Gauci (eds.). British Influences on International Law, 1915-2015. Leiden, Boston: BRILL. p. 162. ISBN 978-90-04-28417-3.

- ^ Mohla, Anika (21 October 2012). "From richest to rags in seven generations". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 14 August 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ Paran Balakrishnan (23 February 2014). "Return of the Royals". The Telegraph. Kolkota. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ Bedi, Rahul (12 April 2008). "India finally settles £1million Nizam dispute". The Telegraph. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Nadeau, Barbie Latza (30 January 2017). "Whose $40 Million Diamond Is It? An Italian Family Feud". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ Bawa, Basant K. (1992). The Last Nizam: The Life and Times of Mir Osman Ali Khan. Viking. p. 377. ISBN 978-0-670-83997-1.

- ^ Mir Ayoob Ali Khan (19 February 2018). "Last surviving son of Nizam, Fazal Jah, dies". Archived from the original on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ "Last Surviving son of seventh Nizam passes away in Hyderabad". Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ "Menace of Black Money: Bring back Nizam's wealth first". Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ "Nizam's heirs seek Pakistani intervention to unfreeze bank account". India Today. 20 July 2012. Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Princess Dürrühsehvar of Berar". The Daily Telegraph. 11 February 2006. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ Leonard, Karen Isaksen (2007). Locating Home: India's Hyderabadis Abroad. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-8047-5442-2.

- ^ a b c Family, Nizam's Family Tree, retrieved 13 October 2021

- ^ "Last Hyderabad Nizam's Heirs Demand 277 Acres Royal Property in Aurangabad". NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ a b Syed Akbar (5 July 2017). "Nizam's heir goes by Blue Book, wants market rate for acquired land". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ "Nizam's grandson basks in grandpa's glory". The Hans India. 27 April 2017. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ a, TNN (9 April 2008). "Paigah scion Mujeeb Yar Jung dead | Hyderabad News - Times of India". The Times of India.

- ^ a b "INDIA: The Nizam's Daughter". Time. 19 January 1959. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ "Last of Hyderabad Nizam's children, Sahebzadi Basheerunnisa Begum passes away". The News Minute. 29 July 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ Akbar, Syed (29 July 2020). "Hyderabad: Sahebzadi Basheerunnisa Begum, last of Nizam's kids, dies". The Times of India. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Mashadi Begum, favourite daughter of Nizam, dead way". Deccan Chronicle. 17 November 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ "Digital Newspaper & Magazine Subscriptions". Retrieved 19 May 2024 – via PressReader.

- ^ Frontline. S. Rangarajan for Kasturi & Sons. 1991. p. 73.

- ^ Sur, Aihik (21 October 2019). "Not 120, over 200 of Nizam kin may claim Hyderabad funds". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ Syed Akbar (1 October 2021). "Hyderabad: Don't project Nizam Mir Osman Ali Khan as a villain for votes, kin writes to PM | Hyderabad News". The Times of India. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ "Floarl Tribute to Nizam VII – The Siasat Daily". siasat.com. 25 February 2018. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ "Heritage enthusiasts pay rich tributes to seventh Nizam". The Hindu. 7 April 2018. Archived from the original on 30 December 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ "In pictures: 50 years ago a sea of people turned up for Death of Hyderabads Last Nizam". thenewsminute.com. 24 February 2017. Archived from the original on 18 December 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ "The Times Group". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ "On his 50th death anniversary, the last Nizam of Hyderabad". Hindustan Times. 24 February 2017. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ "Nizam's opulence has no takers". The Hans India. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ Syed Akbar (25 February 2017). "Mir Osman Ali Khan: Modern Hyderabad architect and statehood icon, Nizam VII fades into history". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Hyderabad (Princely State)". The Indian Princely States Website. Archived from the original on 7 January 2003. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ "Page 3 | The Gazette". Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ "No. 28559". The London Gazette. 12 December 1911. p. 9357.

- ^ Shanker, CR Gowri (27 May 2018). "Nizam VII cared more for people than himself". Deccan Chronicle.

- ^ a b c d e f Cannadine, David (2002). Ornamentalism: How the British Saw Their Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515794-9. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Safvi, Rana (16 February 2019). "In the Chishti shrine in Ajmer". The Hindu.

Further reading

[edit]- The Splendour of Hyderabad: The Last Phase of an Oriental Culture (1591–1948 A.D.) By M.A. Nayeem ISBN 81-85492-20-4

- The Nocturnal Court: The Life of a Prince of Hyderabad By Sidq Jaisi

- Developments in Administration Under H.E.H. the Nizam VII By Shamim Aleem, M. A. Aleem Developments in Administration Under H.E.H. the Nizam VII

- Jewels of the Nizams (Hardcover) by Usha R. Krishnan (Author) ISBN 81-85832-15-3

- Fabulous Mogul: Nizam VII of Hyderabad By Dosoo Framjee Karaka Published 1955 D. Verschoyle, Original from the University of Michigan Fabulous Mogul: Nizam VII of Hyderabad

- The Seventh Nizam: The Fallen Empire By Zubaida Yazdani, Mary Chrystal ISBN 0-9510819-0-X

- The Last Nizam: The Life and Times of Mir Osman Ali Khan By V.K. Bawa, Basant K. Bawa ISBN 0-670-83997-3

- The Seventh Nizam of Hyderabad: An Archival Appraisal By Sayyid Dā'ūd Ashraf The Seventh Nizam of Hyderabad: An Archival Appraisal

- Raghavendra Rao, D (27 July 1926). Misrule of the Nizam: being extracts from and translations of articles regarding the administration of Mir Osman Ali Khan Bahadur, the Nizam of Hyderabad, Deccan. "Swarajya" Press. OCLC 5067242.

- Photographs of Lord Willingdon's visit to Hyderabad in the early 1930s. 27 July 1931. OCLC 33453066.

- Law, John (1914). Modern Hyderabad (Deccan). Thacker, Spink and Co.

- Faruqui, Munis D. (2013). "At Empire's End: The Nizam, Hyderabad and Eighteenth-century India". In Richard M. Eaton; Munis D. Faruqui; David Gilmartin; Sunil Kumar (eds.). Expanding Frontiers in South Asian and World History: Essays in Honour of John F. Richards. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–38. ISBN 978-1-107-03428-0.

External links

[edit]- 1886 births

- 1967 deaths

- Rajpramukhs

- Hyderabadi Muslims

- 20th-century Indian philanthropists

- India MPs 1957–1962

- India MPs 1962–1967

- Lok Sabha members from Andhra Pradesh

- 20th-century Indian educational theorists

- Monarchs who abdicated

- People from Marathwada

- 20th-century Indian royalty

- Madhya Bharat politicians

- Founders of Indian schools and colleges

- Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India

- Indian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire

- Bailiffs Grand Cross of the Order of St John

- Asaf Jahi dynasty

- Nizams of Hyderabad

- Indian philanthropists