Oriental Crisis of 1840

| Oriental Crisis of 1840 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Egyptian–Ottoman War (1839–1841) | |||||||

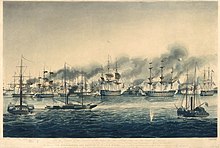

The bombardment and capture of St Jean d'Acre | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

The Oriental Crisis of 1840 was an episode in the Egyptian–Ottoman War in the eastern Mediterranean, triggered by the self-declared Khedive of Egypt and Sudan Muhammad Ali Pasha's aims to establish a personal empire in Ottoman Egypt.

Background

[edit]In the preceding decades, Muhammad Ali had expanded and strengthened his hold on Ottoman territory, beginning with Egypt, where he acted as a viceroy for the Sultan. Called upon to assist the Ottomans in the Greek War of Independence, Muhammad Ali in return demanded parts of Ottoman Syria to be transferred to his personal rule. When the war ended and the Porte failed to keep its promise, Muhammad Ali launched a military campaign against his Ottoman masters and easily took most of the Syrian lands.

Syrian War

[edit]

In 1839, the Ottoman Empire attempted to retake Syria from Muhammad Ali but was defeated by his son, Ibrahim Pasha in the Battle of Nezib. Thus, a new war between Muhammad Ali and the Ottomans escalated, with the latter failing once again to wage it successfully. In June 1840, the entire Ottoman navy defected to Muhammad Ali, and the French planned to offer full support to his cause.[1]

On the verge of total collapse and defeat to Muhammad Ali, an alliance of European powers comprising Britain, the Austrian Empire, Prussia and Russia decided to intervene on behalf of the young Sultan Abdülmecid I.

Convention of London

[edit]By the Convention of London, signed on 15 July 1840, the Great Powers offered Muhammad Ali and his heirs permanent control over Egypt, Sudan, and the Eyalet of Acre if those territories would nominally remain part of the Ottoman Empire. If he did not accept the withdrawal of his forces within ten days, he would lose the offer in southern Syria. If he delayed acceptance more than 20 days, he would forfeit everything offered.[2] The European powers agreed to use all possible means of persuasion to affect the agreement, but Muhammad Ali hesitated since he believed in support from France.[3]

French position

[edit]The French, under the newly-formed cabinet of Prime Minister Adolphe Thiers, sought to increase French influence in North Africa after their conquest of Algeria. Supporting Muhammad Ali's thus-successful revolt seemed suitable. Counter Admiral Julien Pierre Anne Lalande was dispatched to the Mediterranean to eventually join forces with the defected Ottoman fleet.[4] However, France became politically isolated when the other Great Powers backed up the Sultan, and Thiers was unprepared to bring his country into open war with Britain. France switched sides and aligned against Muhammad Ali in October 1840.

Military campaign

[edit]

In September 1840, the European powers eventually moved from diplomatic means to military action. When French support for Muhammad Ali failed to materialize, British and Austrian naval forces in the eastern Mediterranean moved against Syria and Alexandria.[5]

Alexandria was the port where the defecting Ottoman fleet had withdrawn. After the Royal Navy and the Austrian Navy first blockaded the Nile delta coastline, they moved east to shell Sidon and Beirut on 11 September 1840. British and Austrian forces then attacked Acre. Following the bombardment of the city and the port on 3 November 1840 a small landing party of Austrian, British and Ottoman troops, which were led personally by the Austrian fleet commander, Archduke Friedrich, took the citadel after Muhammad Ali's Egyptian garrison in Acre had fled.

Long-term results

[edit]This article may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (December 2024) |

After the surrender of Acre, Muhammad Ali finally accepted the terms of the Convention on 27 November 1840. He renounced his claims over Crete and the Hijaz and agreed to downsize his naval forces and his standing army to 18,000 men if he and his descendants would enjoy hereditary rule over Egypt and Sudan, an unheard-of status for an Ottoman viceroy.[6] Indeed, a firman was issued by the sultan and confirmed Muhammad Ali's rule over Egypt and the Sudan. Muhammad Ali withdrew from Syria, the Hijaz, the Holy Land, Adana and Crete and handed back the Ottoman fleet.

Ecologist Andreas Malm marked the intervention as the pivotal event in the history of the Middle East and the climate system, suggesting that the British ability to project power led to the export of fossil fuel use across the world. In addition, the intervention left Egypt economically subordinate, undergoing the most extreme deindustrialization of any country in the 19th century, and the decisive bombardments by coal-powered steamships and reports of desolation in Palestine emboldened British and American Christian Zionists, whose interests coincided with the foreign policy interests of Lord Palmerston. Malm argues that this aftermath laid the groundwork for the later Zionist movement and began the first conception of a Jewish state as a "satellite colony" that would forward the political and economic interests of the West in the Middle East, which through the 20th and 21st century have been intertwined with the petroleum industry.[7]

See also

[edit]- History of Ottoman Egypt

- History of the Ottoman Empire

- History of Egypt under the Muhammad Ali dynasty

References

[edit]- ^ Efraim Karsh, Inari Karsh, Empires of the Sand: The Struggle for Mastery in the Middle East, 1789–1923, (Harvard University Press, 2001), 36–37.

- ^ Geoffrey G. Butler, Simon Maccoby, The Development of International Law, p. 440

- ^ Efraim Karsh, Inari Karsh, Empires of the Sand: The Struggle for Mastery in the Middle East, 1789–1923, (Harvard University Press, 2001), 38.

- ^ Efraim Karsh, Inari Karsh, Empires of the Sand: The Struggle for Mastery in the Middle East, 1789–1923, (Harvard University Press, 2001), 37.

- ^ H. Wood Jarvis, Pharaoh to Farouk, (London: John Murray, 1956), 134.

- ^ Morroe Berger, Military Elite and Social Change: Egypt Since Napoleon, (Princeton, New Jersey: Center for International Studies, 1960), 11.

- ^ Malm, Andreas (8 April 2024). "The Destruction of Palestine Is the Destruction of the Earth". Verso Books. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Houghton, John. "The Egyptian Navy of Muhammad Ali Pasha." The Mariner's Mirror 105.2 (2019): 162–182.

- Mahmoud, Muhammad. "The international position on the Egyptian control of the Levant 1813–1840 AD." Adab Al-Rafidayn 50.82 (2020): 665–698. online

- Malm, Andreas. "The Destruction of Palestine Is the Destruction of the Earth". (Verso Books, 8 April 2024) online.

- Middleton, Charles R. "Cabinet Decision Making at the Accession of Queen Victoria: The Crisis of the East 1839–1840," Journal of Modern History (1979) 51#2 pp. D1085–D1117 in JSTOR

- Molatam, Mona Mohamed, Ashraf Mo'nes, and Samah Abd Elrahman Mahmoud. "The Firman 'Decree' 1841 to Keep the Rule of Egypt Generally." Minia Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research MJTHR 14.1 (2022): 130–144. online

- Rodkey, Frederick Stanley. "4. Colonel Campbell's Report on Egypt in 1840, with Lord Palmerston's Comments1." Cambridge Historical Journal 3.1 (1929): 102–114.

- Soliman, Ali A., and M. Mabrouk Kotb. "Egypt’s Finances and Foreign Campaigns, 1810–1840." Global Dimensions of African Economic History 18 (2019): 19+ online.

- Ufford, Letitia W. The Pasha: How Mehemet Ali Defied the West, 1839–1841 (McFarland, 2007) online.