Oil and gas industry in the United Kingdom

The oil and gas industry plays a central role in the economy of the United Kingdom.[1] Oil and gas account for more than three-quarters of the UK's total primary energy needs.[2] Oil provides 97 per cent of the fuel for transport, and gas is a key fuel for heating and electricity generation. Transport, heating and electricity each account for about one-third of the UK's primary energy needs. Oil and gas are also major feedstocks for the petrochemicals industries producing pharmaceuticals, plastics, cosmetics and domestic appliances.[2]

Although UK Continental Shelf production peaked in 1999, in 2016 the sector produced 62,906,000[3] cubic metres of oil and gas, meeting more than half of the UK's oil and gas needs. There could be up to 3.18 billion cubic metres of oil and gas still to recover from the UK's offshore fields.

In 2017, capital investment in the UK offshore oil and gas industry was £5.6 billion. Since 1970 the industry has paid almost £330 billion in production tax. About 280,000 jobs in the UK are supported by oil and gas production. The UK oil and gas supply chain services domestic activities and exports about £12 billion of goods and services to the rest of the world.[2]

Overview

[edit]The oil and gas industry in the United Kingdom produced 1.42 million BOE per day[4] in 2014, of which 59%[4] was oil/liquids. In 2013 the UK consumed 1.508 million barrels per day (bpd) of oil and 2.735 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of gas,[5] so is now an importer of hydrocarbons having been a significant exporter in the 1980s and 1990s.

98% of production comes from offshore fields[6] and the services industry in Aberdeen has been a leader in developing technology for hydrocarbon extraction offshore. Historically most gas came from Morecambe Bay and the Southern North Sea off East Anglia and Lincolnshire, but both areas are now in decline. Oil comes mainly from the North Sea Central Graben close to the median line with Norway in two main clusters – around the Forties oilfield east of Aberdeen and the Brent oilfield east of Shetland. There have been recent discoveries in challenging conditions west of Shetland.[1] As of 2012[update] there were 15,729 kilometres (9,774 mi) of pipelines linking 113 oil installations and 189 gas installations.[7] The only major onshore field is Wytch Farm in Dorset but there are a handful oil wells scattered across England. There is significant shale potential in the Weald and in the Bowland Shale under Lancashire & Yorkshire, but only a few wells have been drilled to date.

The UK's strengths in financial services have led it to play a leading role in energy trading through markets such as ICE Futures (formerly the International Petroleum Exchange). The price of Brent Crude from the British North Sea remains the major benchmark for the international oil trade, and the National Balancing Point market is the benchmark for most of the gas traded across Europe.[8] The difficult offshore conditions make the UK a high-cost producer; in 2014 the average development cost was $20.40/boe and the operating cost was $27.80/boe for a total of $48.20/boe.[4] In 2014 the industry spent £1.1bn on exploration, £14.8bn on capital investment and £9.6bn on operating costs.[4] Fields developed since 1993 are taxed through an additional corporation tax on profits, in 2014 the industry generated £2.8bn in direct taxes.[4]

Current status

[edit]Combined oil and gas production volumes in the UK were 1.3 million BOE/day in 2021 and 2022, of which 60% was oil and 40% natural gas production.[9]

Early history

[edit]After the Scottish shale oil industry reached its peak in the 19th century, the British government became increasingly concerned to find secure sources of fuel oil for the Royal Navy. This led to a nationwide search for onshore oil during the First World War and a modest discovery of oil at Hardstoft in Derbyshire.

The UK relied on imports of fuel from the United States and the Middle East. Imports in the period 1912 to 1919 were as follows.[10][11]

| UK import 1912 | Port of London import 1913 | Port of London import 1919 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil type | Import m3 | Value £/m3 | Import m3 | Value £/m3 | Import m3 | Value £/m3 |

| Crude oil | 51.0 | 4.45 | – | – | – | – |

| Lamp oil | 665,353 | 1.54 | 317,618 | 3.67 | 284,534 | 9.13 |

| Petroleum spirit | 379,872 | 3.45 | 318,955 | 8.06 | 575,077 | 17.32 |

| Lubricating oil | 301,835 | 2.31 | 119,542 | 7.92 | 145,222 | 22.58 |

| Fuel oil | 217,864 | 0.89 | 215,691 | 2.73 | 189,772 | 6.00 |

| Gas oil | 333,845 | 1.15 | – | – | – | – |

The country's oil resources were nationalised by the Petroleum (Production) Act 1934 (24 & 25 Geo. 5. c. 36), and a fresh attempt was made to find oil on the UK mainland. The outbreak of World War II accelerated this search and led to a number of wells being drilled, primarily around Eakring in the East Midlands near Sherwood Forest. During World War II over 300,000 tons of oil or 2,250,000 barrels was produced by 170 pumps; and production continued until the mid-1960s.[12] Viable oil extraction also occurred at D'Arcy, Midlothian with 30,654 barrels of oil produced in the period 1937–1965.[13]

In the 1950s, the focus turned to southern England where oil was discovered in the Triassic Sherwood Sands formation at 1,600 metres (5,200 ft), followed by the development of the Wytch Farm oilfield. The link between onshore and offshore oil in the North Sea was made after the discovery of the Groningen gas field in The Netherlands in 1959.[14]

Exploration and appraisal

[edit]Drilling

[edit]Since 1965, 3,970[15] exploration and appraisal wells have been drilled offshore on the United Kingdom Continental Shelf. In 2014, 104 new wells and 54 sidetracks were drilled.[4]

Over four decades since the 1960s, the industry has spent £58 billion by 2008 (equivalent to £98 billion in 2023)[16] on exploration drilling.[17] In 2008, £1.4 billion was spent finding new oil and gas reserves.[17]

Discoveries

[edit]In 2008, 300–400 million barrels (48,000,000–64,000,000 m3) of oil and gas equivalent (BOE) were discovered. The average size of the oil and gas fields discovered between 2000 and 2008 was 26 million BOE,[18] compared with an average of 248 million BOE in the ten years from 1966.[18]

In 2014, between 2.2 to 4.4 to 8.6 billon barrels worth of oil embedded in oil shale was discovered in the Weald Basin, although it is unlikely to be recoverable.[19]

Production

[edit]In 2008, the UK was the 14th largest oil and gas producer in the world (10th largest gas producer and 19th largest oil producer).[20] In Europe the UK is second only to Norway in oil and gas production.

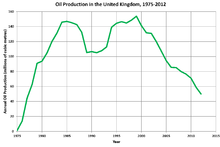

Oil and gas production from the UK sector of the North Sea peaked in 1999, but the UK remains a substantial producer today. Over the last four decades, 39 billion BOE have been extracted on the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS).[21] In 2008, the combined production of oil and gas was 1 billion BOE (549 million barrels (87,300,000 m3) of oil and 68 billion cubic metres of gas). This represented a fall of 5% compared with 2007 (6% oil and 3% gas), a slight improvement on the decline rate in 2002-2007 which averaged 7.5% per annum.[22]

Role in supplying energy to the UK

[edit]As of 2008, just over three-quarters of the UK's primary energy demand was met by oil and gas. In 2008, oil produced on the UKCS satisfied almost all domestic consumption (97%) while gas produced in the UK met about three quarters of demand.[15] In 2020, it is estimated that 70% of primary energy consumed in the UK will still come from oil and gas, even upon achievement of the government's target to source 20% of energy from renewable sources.[22] This will be a combination of oil and gas produced domestically and imports. The UKCS has the potential to satisfy 40% of the UK's oil and gas demand in 2020, if investment is sustained.[22]

Associated expenditure

[edit]Over the last four decades, a total of £210 billion (2008 money, equivalent to £354 billion in 2023)[16] has been invested in developing new resources.[22] In 2008, this figure was £4.8 billion,[15] a 20% decrease since 2006. An additional £147 billion (2008 money)[15] has been spent on producing the oil and gas and in 2008, operating costs were £6.8 billion (equivalent to £10 billion in 2023),[16] an increase on 2007. The development cost of some of the early UK North Sea oil fields are shown in the table:[23]

| Field | Production start | Development cost $ million | Peak production 1,000 barrels/day | $/barrel/day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argyll | 1975 | 70 | 70 | 1,000 |

| Forties | 1975 | 1,460 | 500 | 2,900 |

| Auk | 1975 | 135 | 80 | 1,700 |

| Piper | 1976 | 750 | 300 | 2,500 |

| Montrose | 1976 | 250 | 60 | 4,100 |

| Beryl | 1976 | 800 | 100 | 8,000 |

| Brent | 1976 | 3,600 | 460 | 8,000 |

| Claymore | 1977 | 540 | 170 | 3,200 |

| Thistle | 1977 | 1,000 | 200 | 5,000 |

| Dunlin | 1978 | 960 | 150 | 6,400 |

| Ninian | 1978 | 2,100 | 360 | 5,800 |

| Heather | 1978 | 450 | 50 | 9,000 |

| Cormorant | 1979 | 740 | 60 | 12,300 |

| Tartan | 1979 | 430 | 85 | 5,100 |

| Buchan | 1979 | 200 | 50 | 4,000 |

| Murchison | 1980 | 725 | 120 | 6,000 |

| Total | 14,210 | 2,815 | 5,000 (mean) |

Tax contribution

[edit]Oil and gas production from the UKCS has contributed £271 billion (2008 money) in tax revenues over the last forty years.[24] In 2008, tax rates on UKCS production ranged from 50 to 75%, depending on the field. The industry paid £12.9 billion[24] in corporate taxes in 2008–9, the largest since the mid-1980s, because of high oil and gas prices. This represented 28% of total corporation tax paid in the UK.[24] It is expected that tax revenues from production will fall to £6.9 billion in 2009-10[24] based on an oil price of $47 per barrel, providing 20% of total corporation taxes. In addition to production taxes, the supply chain contributes another £5-6 billion per year in corporation and payroll taxes.[22]

Gas and oil infrastructure

[edit]

A schematic overview of the sources, flow, infrastructure, processes and export routes of UK oil and gas is shown on the schematic, adapted from.[25] Further details are given in the following tables. The infrastructure used to transport gas from offshore gas fields to the gas National Transmission System is shown in the table below.[26][2][15][22][27][28][29][30] This includes import routes of gas from other sources.

| Gas source | Pipeline | Receiving Terminal | National Grid Terminal (NTS entry) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sean hub | 30-inch | Shell Bacton | NG Bacton | |

| Leman West hub | 30-inch | Shell Bacton | NG Bacton | |

| Clipper hub | 24-inch | Shell Bacton | NG Bacton | |

| Shearwater Elgin SEAL hub | 34-inch SEAL | Shell Bacton | NG Bacton | |

| Leman East hub | 2 × 30-inch | Perenco Bacton | NG Bacton | |

| Cygnus, Trent | 24-inch | Perenco Bacton | NG Bacton | |

| Thames | 24-inch | Perenco Bacton | NG Bacton | |

| Lancelot A | 20-inch LAPS | Perenco Bacton | NG Bacton | |

| Hewett | 2 × 30-inch | Perenco Bacton | NG Bacton | |

| LOGGS hub | 36-inch | Theddlethorpe (formerly ConocoPhillips) | NG Theddlethorpe see note | Closed demolished |

| Viking hub | 28-inch | Theddlethorpe | NG Theddlethorpe | Closed demolished |

| Pickerill | 24-inch | Theddlethorpe | NG Theddlethorpe | Closed demolished |

| Caister Murdoch System CMS hub | 26-inch | Theddlethorpe | NG Theddlethorpe | Closed demolished |

| West Sole | 16-inch, 24-inch | Easington | NG Easington | |

| Cleeton | 36-inch | Dimlington | NG Easington | |

| Rough | 36-inch, 16-inch | Easington | NG Easington | |

| Amethyst | 30-inch | Easington | NG Easington | Field decommissioned |

| Tolmount | 20-inch | Easington | NG Easington | |

| Breagh | 20-inch | Teesside Gas Processing Plant TGPP | NG Teesside | |

| CATS riser & Everest platform | 36-inch CATS | Teesside | NG Teesside | |

| Frigg via MCP1 | 2 × 30-inch | St Fergus | NG St Fergus | Closed |

| Brent & some Norwegian fields | 36-inch FLAGS | St Fergus | NG St Fergus | |

| Beryl A | 30-inch SAGE | St Fergus | NG St Fergus | |

| Miller | 30-inch | St Fergus | NG St Fergus | Closed |

| Fulmar | 20-inch | St Fergus | NG St Fergus | |

| South Morecambe | 30-inch | South Morecambe Rampside | NG Barrow | Closed |

| North Morecambe | 30-inch | North Morecambe Barrow | NG Barrow | |

| ‘Rivers’ fields | 24-inch | Rivers terminal then to North Morecambe terminal | – | |

| Douglas | 24-inch | Point of Ayr | NG Burton Point | |

| Gas import from outside the UK | ||||

| Balgzand, Netherlands | 36-inch Bacton–Balgzand BBL | Shell Bacton | NG Bacton | |

| Zeebrugge, Belgium | 40-inch UKI Interconnector | National Grid Bacton | NG Bacton | |

| Nyhamna & Sleipner, Norway | 44-inch Langeled | Easington | NG Easington | |

| Gormanston, Ireland | 18-inch | Ballyalbanagh, Co. Antrim | Gas flow into Northern Ireland via the South North Pipeline (SNP) | |

| Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) | Tanker and storage | Grain LNG | NG Isle of Grain | |

| LNG | Tanker and storage | South Hook | NG South Hook | |

| LNG | Tanker and storage | Dragon | NG Dragon | |

Note: The Theddlethorpe reception terminal and the National Grid terminal have been demolished.

The gas export routes from the UK are as follows:

| Gas source | Export terminal | Pipeline | Receiving terminal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shell fields | Shell Bacton | 36-inch Bacton–Balgzand BBL | Balgzand, Netherlands |

| NTS Bacton | National Grid Bacton | 40-inch UKI Interconnector | Zeebrugge, Belgium |

| NTS Moffat | Moffat–Brighouse Bay, Scotland | 24-inch UK-Irish Gas interconnector 1 | Gormanston, Ireland |

| NTS Moffat | Moffat–Brighouse Bay, Scotland | 30-inch UK-Irish Gas interconnector 2 | Gormanston, Ireland; 10-inch spur to Isle of Man |

| Markham, Chiswick, Grove 24-inch pipeline | J6-A platform, Netherlands | WGT (+ extension) pipeline | Den Helder, Netherlands |

| Minke, Orca, Sillimanite, Wingate 8-inch, 12-inch, 12-inch pipelines | D15-FA platform, Netherlands | Noordgastransport pipeline | Uithuizen, Netherlands |

Pipeline acronyms

BBL – Bacton–Balgzand Line; CATS – Central Area Transmission System; FLAGS – Far North Liquids and Associated Gas System; LAPS – Lancelot Area Pipeline System; LOGGS – Lincolnshire Offshore Gas Gathering System; MCP01 – Manifold Compression Platform 01; SAGE – Scottish Area Gas Evacuation; SEAL – Shearwater Elgin Area Line; UKI – United Kingdom Interconnector 1.

The infrastructure used to transport oil from UK offshore oil fields for use or export is shown in the table below:[26]

| Oil source | Pipeline | Receiving Terminal | Then to: | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forties pipeline system | 36-inch | Cruden Bay | Kinneil facility | |

| Piper platform | 30-inch | Flotta terminal | Crude stabilization then tanker loading of stabilized crude | |

| Claymore platform | 30-inch | Claymore TEE on Piper-Flotta line | – | |

| Ninian Central hub | 36-inch | Sullom Voe | Crude stabilization then tanker loading of stabilized crude | |

| Brent C hub via Cormorant A | 36-inch | Sullom Voe | ||

| Clair platform | 22-inch | Sullom Voe | ||

| Fields produced by FPSO or using tanker e.g. Alba FSU, Captain FPSO, Douglas CALM & FPSO, Gryphon A | – | – | UK and international markets | |

| Norwegian field produced through the UK | ||||

| Ekofisk | 34-inch NORPIPE | Teesside | ||

For a full list see Oil terminals in the United Kingdom

Employment

[edit]In 2008, some 450,000 jobs throughout the United Kingdom were supported by the servicing of activity on the UKCS and in the export of oil and gas related goods and services around the world.[22] The exploration for and extraction of oil and gas from the UKCS accounted for around 350,000 of these; this comprised 34,000 directly employed by oil and gas companies and their major contractors, plus 230,000 within the wider supply chain. Another 89,000 jobs were supported by the economic activity induced by employees' spending. In addition, a thriving exports business is estimated to support a further 100,000 jobs.[22] In January 2013 an Industry Job Site www.oilandgaspeople.com predicted that over 50,000 new jobs would be created within the industry that year as new technology makes marginal fields more viable.

Whilst the oil and gas industry provides work across the whole of the UK, Scotland benefits the most, with around 195,000 jobs, or 44% of the total. 21% of the workforce is from South East England, 15% from the North of England, and 12% from the East of England . Each £billion spent on the UKCS supports approximately 20,000 jobs.[22]

Companies database

[edit]Set up in 1996, First Point Assessment Limited (FPAL)[31] is the key tool used by oil and gas companies to identify and select current and potential suppliers when awarding contracts or purchase orders. The organisation operates as a neutral, industry-steered organisation, improving efficiency in the oil and gas supply chain. FPAL currently matches the needs of over 70 purchasing organisations with the capabilities of over 2,400 suppliers. This organisation is dissolved as of 5 September 2017.

Tax contribution

[edit]Jobs in the UK oil and gas industry are highly skilled and well rewarded. 2008 salaries averaged circa £50,000 a year across a broad sample of supply chain companies, with the Exchequer benefiting by £19,500 per head in payroll taxes.[22]

Technology and innovation

[edit]The operating environment in the waters around the UK is harsh and demanding. To overcome the challenges of recovering oil and gas from increasingly difficult reservoirs and deeper waters, the North Sea has developed a position at the forefront of offshore engineering, particularly in subsea technology. Many new oil and gas fields in the UK are small, technically complex and economically marginal. Often recovery from these fields is achieved by subsea developments tied back to existing installations and infrastructure, over varying distances measured in tens of kilometres. Innovative technology is also a critical component in the recovery of reserves from high pressure, high temperature (HPHT), heavy crude oil and deep water fields.

Exports

[edit]UK exports of oil-related goods and services have been estimated at more than 10 billion a year in value.[22] This amount is a reflection of how well established the UK's supply chain is internationally. The competence of its people and the quality of its technology, particularly subset, are very much in demand in oil and gas provinces around the world.

Industry collaboration

[edit]The Industry's Technology Facilitator (ITF)[32] identifies needs and facilitates the development of new technology to meet those needs through joint industry projects with up to 100% funding available for promising solutions. Since its creation ten years ago, ITF has helped oil and gas producers, service companies and technology developers to work collaboratively, developing 137 technology projects.

Health and safety

[edit]Background

[edit]The safety, health and welfare of offshore workers in the United Kingdom's sector of the North Sea had been secured since 1971 by the Mineral Workings (Offshore Installations) Act 1971 and its subsidiary legislation.[33] The Health and Safety at Work, etc. Act 1974 was administered on behalf of the Health and Safety Executive by the Petroleum Engineering Division of the Department of Energy.[33]

Following the Piper Alpha disaster in 1988, the 106 recommendations of the Public Inquiry by Lord Cullen proposed fundamental changes to the regulation of offshore safety.[34] These included the preparation and publication of Safety Cases, the strengthening of Safety Management Systems, independent assessment and survey, legislative changes and changing the regulatory body.[35] Responsibility for offshore safety was transferred in 1991 from the Department of Energy to the Health and Safety Executive. The Offshore Safety Act 1992 legally implemented many of the Inquiry recommendations.[35]

Regulator

[edit]The Health & Safety Executive (HSE)[36] is the UK offshore oil and gas industry regulator and is organised into a number of directorates. The Hazardous Installations Directorate (HID) is the operational arm responsible for major hazards. A dedicated Offshore Division within HID is responsible for the enforcement of regulations in the offshore oil and gas industry.

Safety vision

[edit]Set up 1997, Step Change in Safety[37] is the UK based cross-industry partnership with the remit to make the UK the safest oil and gas exploration and production province in the world. Its initial aim was to reduce the injury rate by 50%, which was achieved in 2003. Step Change in Safety's work is now focused in three areas: recognising hazards and reducing risk, personal ownership for safety and asset integrity. Communication between Step Change in Safety and the industry is through elected safety representatives, offshore installation managers and supervisors, safety professionals and company focal points. These individuals are consulted on what needs to be done and are charged with ensuring that the Step Change programme is implemented.

Statistics

[edit]HSE publishes fatal, major and over-three-day injuries as well as dangerous occurrences under the Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations (RIDDOR).

RIDDOR does not apply to events that are reportable under the Air Navigation (Investigation of Air Accidents involving Civil and Military Aircraft or Installations) Regulations 1986;[38] the Civil Aviation (Investigation of Air Accidents) Regulations 1989; and the Merchant Shipping Act 1988, and orders and regulations made thereunder – therefore, industry-related aviation and marine accidents which are covered by any of the above regulations are not included in the RIDDOR-derived statistics. In 2007/8 and 2008/9, there were no fatalities, compared with two in 2006/7 and 2005/6. During 2008/9, 30 major injuries were reported compared with 44 in 2007/8. This resulted in a combined fatal and major injury rate of 106 per 100,000 workers, down from 156 and 146 in 2007/8 and 2006/7 respectively. The number of over-three-day injuries has fallen this year by 5% to 140, representing an over-three-day injury rate of 496 per 100,000 workers.

Aviation safety

[edit]Aberdeen is the busiest heliport in the UK with 47,000 flights in 2008 transporting workers to and from offshore installations on the UKCS.[39] Between 1977 and the end of 2006, just over 56 million passengers were transported by helicopter from all UK heliports to and from offshore installations on the UKCS. More than 6.5 million sectors were flown, taking nearly 3 million flying hours. During this time, seven fatal helicopter accidents claimed the lives of 94 offshore workers and flight crew.[40] Government data for the period 1995 to 2004 show that with the exception of rail, the yearly passenger casualty rate for offshore helicopter travel is much better than most forms of land-based passenger transport and of a similar order to travelling by car.[40] Offshore helicopter passengers are equipped for their journey with survival suits and other aids and undergo survival training.

Other mariners' safety

[edit]The Fisheries Legacy Trust Company's (FLTC)[41] main function is to help keep fishermen safe in UK waters. It does this by building a trust fund (based on payments from oil and gas producers) which can be used to maintain comprehensive, up-to-date information on all seabed hazards related to oil and gas activities for as long as they remain, and to make this data available for use by fishing vessel plotters found on board in wheelhouses all around the UK coastline.

Environment

[edit]The industry's vision which guides the environmental management process is to understand and manage environmental risks to achieve demonstrable no harm levels by 2020.

Atmospheric emissions

[edit]UK oil and gas installations participate in the European Union Emission Trading Scheme (EU ETS) which aims to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide and combat the threat of climate change. Carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere in three ways during production operations: combustion of fuel for power generation, flaring (a process used to burn off unusable waste gas or flammable gas and liquids for safety reasons) and direct process emissions. Over the years, carbon dioxide emissions in tonnes have steadily decreased with a 10% reduction in 2007 compared with 2000.[42] In 2007, 17 million tonnes of carbon dioxide were emitted.

Flaring

[edit]

Open gas flares for well tests are not permitted in the UK. Release of unburned gas is also not permitted by the Environment Agency/SEPA.[43] The low temperature of combustion in open flaring, and incomplete mixing of oxygen means that carbon in methane may not be burned, leading to a sooty smoke, and potential VOC/BTEX contamination. Radon gas exists in very low concentrations in shale gas and in North Sea gas, but the levels predicted fall below any level of concern (300 microseiverts p.a.).

In exploration wells, where flow rates are expected to be 10 tonnes of gas per day, testing is licensed by the Environment Agency to 30 days, extendable to 90 days. Enclosed burners are available that will ensure low levels of light pollution, little noise, and 99+% combustion and destruction of VOCs/BTEX, at around 800 C.[44]

Well testing is used to estimate the productivity of the well. In testing a production well, the test can be made by flowing into the production pipeline. This means that no gases would be lost, and flaring would not be necessary. This is known as a 'green completion'.

Marine discharges

[edit]Discharges into the sea can occur either through accidental release (e.g. oil spill) or in the course of normal operations. In 2007, 59 tonnes of oil in total[42] was accidentally released into the marine environment, which, in open sea, will have a negligible environmental impact.

Waste

[edit]Types of waste generated offshore vary and include drill cuttings and powder, recovered oil, crude contaminated material, chemicals, drums, containers, sludges, tank washings, scrap metal and segregated recyclables. The majority of wastes produced offshore are transferred onshore where the main routes of disposal are landfill, incineration, recycling and reuse. Drill cuttings are also re-injected into wells offshore.

Future of the UKCS

[edit]Production

[edit]

39 billion barrels (6.2×109 m3) of oil and gas have been produced on the UKCS and up to 25 billion barrels (4.0×109 m3) are left.[22] Therefore, the UK could still be producing significant amounts of oil and gas for decades to come. It is estimated that in 2020, UK production could still meet 40%[22] of the nation's demand for oil and gas.

Decommissioning

[edit]The principal legislation for decommissioning offshore infrastructure when production ceases is OSPAR Decision 98/3 on Disposal of Disused Offshore Installations. Under OSPAR legislation, only installations that fulfil certain criteria (on the grounds of safety and/or technical limitations) are eligible for derogation (that is, leaving the structure, or part of, in place on the seabed). All other installations must be totally removed from the seabed. During the next two decades, the industry will begin to decommission many of the installations that have been producing oil and gas for the past forty years. There are approximately 470 installations to be decommissioned, including very large ones with concrete sub-structures, small, large and very large steel platforms, and subsea and floating equipment, the vast majority of which will have to be totally removed to the shore for dismantling and disposal. Some 10,000 kilometres of pipelines, 15 onshore terminals and around 5,000 wells are also part of the infrastructure planned to be gradually phased out, although some, or parts, of the onshore terminals will remain because they are import points for gas pipelines from Norway and the Netherlands. Decommissioning is a complex process, representing a considerable challenge on many fronts and encompassing technical, economic, environmental, health and safety issues. Expenditure is therefore projected to be £19 billion by 2030, rising to £23 billion by 2040, for existing facilities. New facilities could add another £2-3 billion to the decommissioning cost, raising the total to circa £25 billion.[22]

Technology

[edit]Exports

[edit]The export of oilfield goods and services developed by the UK over forty years are in demand around the world. In 2008, approximately £5 billion[22] was earned through such exports. As energy demand around the world grows, so too will the need for technology and expertise required to satisfy it.

Transfer to other industries

[edit]Marine technology, skills and expertise pioneered in oil and gas are important in the design, installation and maintenance of offshore wind turbines and hence have found roles in the continuing evolution of renewable energy. The industry has led the way in the development of drilling, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and geophysical technology. All three areas of expertise are used by scientists and engineers elsewhere, whether examining Antarctic ice core samples, raising sunken ship wrecks or studying the plate tectonics of the ocean floor.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS)

[edit]To prevent carbon dioxide building up in the atmosphere it has been theorised that it can be captured and stored, such as the working CCS at the Sleipner field offshore Norway, among other examples. CCS is undertaken by combining three distinct processes: capturing the carbon dioxide at a power station or other major industrial plant, transporting it by pipeline or by tanker, and then storing it in geological formations. Some of the best natural repositories are depleted oil and gas fields, such as those in the North Sea. The oil and gas industry's knowledge of undersea geology, reservoir management and pipeline transport will play an important role in making this technology work effectively.

See also

[edit]- Petroleum Act

- Gas Act

- North Sea oil

- List of oil and gas fields of the North Sea

- Onshore oil and gas fields in the United Kingdom

- Oil terminals in the United Kingdom

- Petroleum refining in the United Kingdom

- Hydraulic fracturing in the United Kingdom

- Shale gas in the United Kingdom

- 2021 United Kingdom fuel crisis

- English land law

- Isle of Man gas industry

- United Kingdom–Ireland natural gas interconnectors

References

[edit]- ^ a b Shepherd, Mike (2015). Oil Strike North Sea: A first-hand history of North Sea oil. Luath Press.

- ^ a b c d "Oil and Gas UK". oilandgas.co.uk. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "United Kingdom Oil Reserves, Production and Consumption Statistics - Worldometer".

- ^ a b c d e f "Activity Survey 2015". Oil & Gas UK. Archived from the original on 2015-02-24. Retrieved 2015-02-24.

- ^ "United Kingdom Country Analysis Brief Overview". Energy Information Administration.

- ^ "Oil Production sorted by Field". www.og.decc.gov.uk. Archived from the original on July 27, 2014.

- ^ "Oil and gas: infrastructure". www.gov.uk. 6 October 2016.

- ^ Macalister, Terry (12 December 2012). "How the £300bn a year wholesale gas market operates". The Guardian.

- ^ "Oil & Gas in the UK". www.ukeiti.org. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ London County Council (1915). London Statistics 1913-14 vol XXIV. London: LCC. p. 489.

- ^ London County Council (1922). London Statistics 1920-21 vol. XXVII. London: LCC. p. 236.

- ^ Levine, Joshua (2015). The Secret History of the Blitz. London: Simon & Schuster. pp. 117–130. ISBN 978-1-4711-3102-8.

- ^ The Search for Natural Petroleum in the Lothians, by Alastair C Bagnall, Oil Exploration (Holdings) Ltd, Edinburgh; in The Edinburgh Geologist, March 1979, publ.by Edinburgh; pp. 12-13 Geological Society edinburghgeolsoc.org/eg_pdfs/issue05_full.pdf - retrieved Nov 2023

- ^ Morton, Michael Quentin (2014). "'What Oilfields?' Onshore Oil in the UK". GeoExpro. 11 (3). Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Department of Energy & Climate Change - GOV.UK". decc.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2013-06-03.

- ^ a b c UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ a b "Income from and Expenditure on UK Continental Shelf Exploration, Development and Operating Activities". Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ a b "Research & consulting: Energy, Mining and Metals - Wood Mackenzie". woodmacresearch.com. 13 June 2017.

- ^ "The Jurassic shales of the Weald Basin: geology and shale oil and shale gas resource estimation" (PDF). British Geological Survey & Department of Energy & Climate Change. 2014.

- ^ "Statistical Review of World Energy 2009 | BP". Archived from the original on August 22, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Oil and Gas - UK Production Data Release". Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Oil & Gas UK - Industry Issues - Standard Agreements - Index Page". Archived from the original on June 19, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ Institute of Petroleum (1978). A guide to North Sea oil and gas technology. London: Heyden & Son. p. 56. ISBN 0855013168.

- ^ a b c d "[ARCHIVED CONTENT] Statistics at HMRC - HM Revenue & Customs - GOV.UK". hmrc.gov.uk.

- ^ Murray, Stephen (2020). "The energyscape of the lower Thames and Medway: Britain's changing patterns of energy use". Landscape History. 41 (1): 99–120. doi:10.1080/01433768.2020.1753985. S2CID 219146452.

- ^ a b Department of Trade and Industry (1994). The Energy Report. London: HMSO. ISBN 0115153802.

- ^ British Gas (1980). Gas Chronology: the Development of the British Gas Industry. London: British Gas.

- ^ Williams, Trevor I. (1981). A History of the British Gas Industry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198581572.

- ^ More, Charles (2009). Black Gold: Britain and Oil in the Twentieth Century. London: Continuum. ISBN 9781847250438.

- ^ Operating Company Fact Sheets (various)

- ^ "FPAL". Achilles.com. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- ^ "The Industry Technology Facilitator - ITF". Oil-itf.com. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- ^ a b Department of Energy (1990). Offshore installations: Guidance on design, construction & certification, 4th Edition. London: HMSO. ISBN 0114129614.

- ^ Cullen, The Hon. Lord William Douglas (1990). The Public Inquiry into the Piper Alpha Disaster, Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Energy by Command of Her Majesty. London: HMSO. ISBN 0101113102.

- ^ a b Crawley, Frank (May 1999). "The change in safety management for offshore oil and gas production systems". Transactions of the Institution of Chemical Engineers. Part B. 77 (3): 143––48. Bibcode:1999PSEP...77..143C. doi:10.1205/095758299529956.

- ^ "HSE: Information about health and safety at work". Hse.gov.uk. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- ^ "Step Change in Safety". stepchangeinsafety.net. Archived from the original on July 3, 2008.

- ^ "Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations 2013 - RIDDOR - HSE". Hse.gov.uk. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- ^ "Aberdeen International Airport homepage". Aberdeenairport.com. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- ^ a b "Working Together, Producing Cleaner Energies. %". www.oilandgasuk.co.uk. Archived from the original on October 4, 2009.

- ^ "FLTC". Ukfltc.com. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- ^ a b "Environment". Oil & Gas UK. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Fracking UK shale: local air quality" (PDF). UK Govt. Retrieved 2016-08-28.

- ^ "Enclosed gas flares". HiTemp Technology. Retrieved 2016-08-28.

Further reading

[edit]- Falkus, M. E. “The British Gas Industry before 1850.” Economic History Review 20#3 1967, pp. 494–508. online

- Fouquet, Roger, and Peter JG Pearson. "A thousand years of energy use in the United Kingdom." The Energy Journal 19.4 (1998) online.

- Fouquet, Roger, and Peter J.G. Pearson. "Seven centuries of energy services: The price and use of light in the United Kingdom (1300-2000)." The energy journal 27.1 (2006) online.

- Goodall, Francis. "Appliance trading activities of British gas utilities, 1875‐1935 1." Economic History Review 46.3 (1993): 543-557 online.

- Kander, Astrid, Paolo Malanima, and Paul Warde. Power to the people: energy in Europe over the last five centuries (Princeton University Press, 2015).

- Matthews, Derek. "Laissez-faire and the London gas industry in the nineteenth century: another look." Economic History Review (1986): 244-263 online.

- Matthews, Derek. "The technical transformation of the late nineteenth-century gas industry." Journal of Economic History (1987): 967-980 online.

- McGaughey, Ewan. Principles of Enterprise Law: the Economic Constitution and Human Rights (Cambridge UP 2022) ch 11

- Millward, Robert, and Robert Ward. "The costs of public and private gas enterprises in late 19th century Britain." Oxford Economic Papers 39.4 (1987): 719–737. online

- Shepherd, Mike. Oil Strike North Sea: A first-hand history of North Sea oil. Luath Press. 2015.

- Thorsheim, Peter. "The Paradox of Smokeless Fuels: Gas, Coke and the Environment in Britain, 1813-1949." Environment and History 8.4 (2002): 381–401. online

- Tomory, Leslie. "The environmental history of the early British gas industry, 1812–1830." Environmental History 17.1 (2012): 29-54 online.