1978 Revelation on Priesthood

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Black people and the Latter Day Saint movement |

|---|

|

The 1978 Declaration on Priesthood was an announcement by leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) that reversed a long-standing policy excluding men of Black African descent from ordination to the denomination's priesthood and both Black men and women from priesthood ordinances in the temple. Leaders stated it was a revelation from God.

Beginning in the 1850s, individuals of Black African descent were prohibited from ordination to the LDS Church's priesthood—in other cases held by all male members who meet church standards of spiritual "worthiness"—and from receiving temple ordinances such as the endowment and celestial marriage (sealing).[1][a] LDS Church presidents Heber J. Grant[2] and David O. McKay[3] are known to have privately stated that the restriction was a temporary one, and would be lifted at a future date by a divine revelation to a church president.

In 2013, the LDS Church posted an essay about race and the priesthood revelation.[4]

Background

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

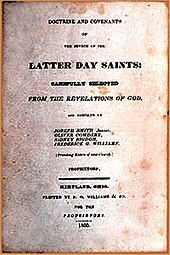

| Doctrine and Covenants |

|---|

|

Men of Black African descent were permitted to hold the priesthood in the early years of the Latter Day Saint movement, when Joseph Smith was alive.[5] After Smith died, Brigham Young became leader of the LDS Church and many were excluded from holding the priesthood. This practice persisted after Young's death, and was maintained until the announcement of the 1978 revelation.

Events leading up to the revelation

[edit]In the decades leading up to the 1978 revelation, it became increasingly difficult for the church to maintain its policy on Africans and the priesthood. The difficulties arose both from outside protests and internal challenges encountered as the membership grew in far away areas of the world outside of the predominantly white Utah. Internal challenges in administering the priesthood ban were mainly due to the difficulty in determining which peoples were of African ancestry in areas such as Brazil, the Philippines and Caribbean and Polynesian Islands as well as shortages of available people for local church leadership positions in areas with a predominantly Black population such as Nigeria or the Dominican Republic.

The majority of the protests against the policy coincided with the rise of the civil rights movement in the United States during the 1960s. In 1963, Hugh B. Brown made a statement on civil rights during General Conference in order to avert a planned protest of the conference by the NAACP.[6] During the late 1960s and 1970s, Black athletes at some universities refused to compete against teams from church owned Brigham Young University.[7] A protest in 1974 was in response to the exclusion of Black scouts to become leaders in church sponsored Boy Scout troops.[8] By 1978, when the policy was changed, external pressure had slackened somewhat.[citation needed]

In the 1960s, an effort was made to establish a church presence in Nigeria where many natives had expressed interest. Church leaders found it difficult to make progress in establishing the church in that region without a change in the priesthood policy.[9] Issues regarding possible expansion in Nigeria were considered in correspondence between the South African Mission and church general authorities from as early as 1946.[5] LDS Church leaders in the Caribbean, notably in the Dominican Republic (described at the time as 98% Black), had expressed the difficulty of proselytizing efforts in the region due to priesthood restrictions.[5]

In 1969, during a weekly meeting the apostles voted to overturn the priesthood ban. However, Harold B. Lee, a senior apostle at the time, was not present due to travel. When he returned he made the argument that the ban could not be overturned administratively but rather required a revelation from God. Lee called for a re-vote, which did not pass.[10]

On March 1, 1975, LDS Church president Spencer W. Kimball announced plans to build a temple in São Paulo, Brazil. Before the 1978 revelation, not only were men of Black African descent denied ordination to the priesthood, but men and women of Black African descent were also excluded from performing most of the various ordinances in the temple. Determining priesthood and temple eligibility in Brazil was problematic due to the considerable intermarriage between Amerindians, Europeans, and Africans since 1500, and high uncertainty in tracing ancestral roots. Furthermore, in the Brazilian culture, racial identification had more to do with physical appearance and social class than blood lines.[11] The cultural differences in understanding race created confusion between the native Brazilians and the American missionaries. When the temple was announced, church leaders realized the difficulty of restricting persons with various bloodlines from attending the temple in Brazil.[12]

During the first half of the 20th century, most church members and leaders believed the priesthood ban had originated with church founder Joseph Smith. Because of this belief, church leaders were hesitant to overturn the ban. Scholars in the 1960s and 1970s found no evidence of the prohibition before Brigham Young.[13]: 196–97 This evidence made it easier for Kimball to consider making a change.[14]

Softening of the policy

[edit]Prior to the complete overturning of the priesthood ban by revelation, several administrative actions were taken to soften its effect.

Before David O. McKay visited the South Africa mission in 1954, the policy was that any man desiring to receive the priesthood in the mission was required to prove a lack of African ancestors in his genealogy. Six missionaries were tasked with assisting in the necessary genealogical research but even then it was often difficult to establish lack of African ancestry.[15] McKay changed the policy to presume non-African ancestry except when there was evidence to the contrary.[16] This change allowed many more people to be ordained without establishing genealogical proof.

Four years later, McKay gave permission for Fijians to receive the priesthood despite their dark skin color. Thus, the priesthood ban was restricted to those people who were specifically of African descent.[16] In 1967, the same policy that was used in South Africa was extended to cover Brazilians as well.[17] In 1974, Black people were allowed to serve as proxies for baptisms for the dead.[18]

Revelation

[edit]This section may rely excessively on sources too closely associated with the subject, potentially preventing the article from being verifiable and neutral. (December 2017) |

In the years prior to his presidency, Spencer W. Kimball kept a binder of notes and clippings related to the issue.[19] In the first years of his presidency, he was recorded as frequently making the issue one of investigation and prayer.[20] In June 1977, Kimball asked at least three general authorities—apostles Bruce R. McConkie, Thomas S. Monson, and Boyd K. Packer—to submit memos "on the doctrinal basis of the prohibition and how a change might affect the Church", to which McConkie wrote a long treatise concluding there were no scriptural impediments to a change.[20] During 1977, Kimball obtained a personal key to the Salt Lake Temple for entering in the evenings after the temple closed, and often spent hours alone in its upper rooms praying for divine guidance on a possible change.[21] On May 30, 1978, Kimball presented his two counselors with a statement he had written in longhand removing all racial restrictions on ordination to the priesthood, stating that he "had a good, warm feeling about it."[22]

On June 1, 1978, following the monthly meeting of general authorities in the Salt Lake Temple, Kimball asked his counselors and the ten members of Quorum of the Twelve Apostles then present[b][23] to remain behind for a special meeting.[24] Kimball began by describing his studies, thoughts, and prayers on removing the restriction and on his growing assurance that the time had come for the change.[24] Kimball asked each of the men present to share their views, and all spoke in favor of changing the policy.[24] After all present had shared their views, Kimball led the gathered apostles in a prayer circle to seek final divine approval for the change.[24] As Kimball prayed, many in the group recorded feeling a powerful spiritual confirmation.[25] Bruce R. McConkie later said: "There are no words to describe the sensation, but simultaneously the Twelve and the three members of the First Presidency had the Holy Ghost descend upon them and they knew that God had manifested his will .... I had had some remarkable spiritual experiences before ... but nothing of this magnitude."[26] L. Tom Perry described: "I felt something like the rushing of wind. There was a feeling that came over the whole group. When President Kimball got up he was visibly relieved and overjoyed."[27] Gordon B. Hinckley later said: "For me, it felt as if a conduit opened between the heavenly throne and the kneeling, pleading prophet of God who was joined by his Brethren."[28]

The church formally announced the change on June 9, 1978. The story led many national news broadcasts and was on the front page of most American newspapers, and in most largely Latter-day Saint communities in Utah and Idaho telephone networks were completely jammed with excited callers.[29] The announcement was formally approved by the church at the October 1978 general conference, and is included in LDS Church's edition of the Doctrine and Covenants as Official Declaration 2.

Revelation accepted at general conference

[edit]On September 30, 1978, during the church's 148th Semiannual General Conference, the following was presented by N. Eldon Tanner, First Counselor in the First Presidency:

In early June of this year, the First Presidency announced that a revelation had been received by President Spencer W. Kimball extending priesthood and temple blessings to all worthy male members of the Church. President Kimball has asked that I advise the conference that after he had received this revelation, which came to him after extended meditation and prayer in the sacred rooms of the holy temple, he presented it to his counselors, who accepted it and approved it. It was then presented to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, who unanimously approved it, and was subsequently presented to all other General Authorities, who likewise approved it unanimously.[30]

On that day, the general conference unanimously voted to accept the revelation "as the word and will of the Lord."[30]

Ramifications

[edit]Following the revelation, Black male members were allowed to be ordained to the priesthood. Black members and their spouses regardless of race were allowed to enter the temple and undergo the temple rituals, including celestial marriages. Black members could be adopted into a tribe of Israel through a patriarchal blessing.[31][32][33] Black members were also allowed to serve missions and hold leadership positions. Proselytization restrictions were removed, so missionaries no longer needed special permission to teach Black people, converts were no longer asked about African heritage, and marks were no longer made on membership records indicating African heritage.

Statements after the revelation

[edit]Later in 1978, apostle Bruce R. McConkie said:

There are statements in our literature by the early brethren which we have interpreted to mean that the Negroes would not receive the priesthood in mortality. I have said the same things, and people write me letters and say, "You said such and such, and how is it now that we do such and such?" And all I can say to that is that it is time disbelieving people repented and got in line and believed in a living, modern prophet. Forget everything that I have said, or what President Brigham Young or President George Q. Cannon or whomsoever has said in days past that is contrary to the present revelation. We spoke with a limited understanding and without the light and knowledge that now has come into the world.... We get our truth and our light line upon line and precept upon precept. We have now had added a new flood of intelligence and light on this particular subject, and it erases all the darkness and all the views and all the thoughts of the past. They don't matter any more.... It doesn't make a particle of difference what anybody ever said about the Negro matter before the first day of June of this year.[34]

On the topic of doctrine and policy for the race ban lifting the apostle Dallin H. Oaks stated in 1988, "I don't know that it's possible to distinguish between policy and doctrine in a church that believes in continuing revelation and sustains its leader as a prophet. ... I'm not sure I could justify the difference in doctrine and policy in the fact that before 1978 a person could not hold the priesthood and after 1978 they could hold the priesthood."[35] In 2013, the LDS Church posted an essay on the priesthood ban, stating that the ban was based more on racism than revelation. The essay places the origin of the ban on Brigham Young, arguing there was no evidence any Black men were denied the priesthood during Joseph Smith's leadership. The essay also disavowed theories promoted in the past including "that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor or curse, or that it reflects actions in a premortal life; that mixed-race marriages are a sin; or that blacks or people of any other race or ethnicity are inferior in any way to anyone else."[4]

Official Declaration 2

[edit]Official Declaration 2 is the canonized formal 1978 announcement by the church's First Presidency that the priesthood would no longer be subject to restrictions based on race or skin color.[36] The declaration was canonized by the LDS Church at its general conference on September 30, 1978, through the process of common consent.[37] Since 1981, the text has been included in the church's Doctrine and Covenants, one of its standard works of scripture.[38] It is the most recent text that has been added to the LDS Church's open canon of scripture.[39] The announcement that was canonized had previously been announced by a June 8, 1978, letter from the First Presidency, which was composed of Spencer W. Kimball, N. Eldon Tanner, and Marion G. Romney.

Unlike much of the Doctrine and Covenants, Official Declaration 2 is not itself presented as a revelation from God. However, its text announces that Jesus Christ "by revelation has confirmed that the long-promised day has come when every faithful, worthy man in the Church may receive the holy priesthood."[30] Thus, it is regarded as "the official declaration of the revelation."[40] No text of the revelation has been released by the church, but it is common for Latter-day Saints to refer to the "revelation on the priesthood" in describing the changes wrought by the announcement and canonization of Official Declaration 2.[41]

Modern disavowal of previously given reasons for restrictions

[edit]Sometime between 2014 and 2015, the LDS Church published an essay titled "Race and the Priesthood". As part of that essay, the church officially stated that the reasons for the previous racial restrictions were unknown, and officially disavowed the racist explanations for the policy, but did not disavow the restrictions themselves.[42] As part of the 40th anniversary celebration of the revelation Dallin H. Oaks said that, "the Lord rarely gives reasons for the commandments and directions He gives to His servants," but acknowledged the hurt that the restrictions caused before they were rescinded, and encouraged all church members to move past those feelings and focus on the future.[43] As of 2019 the LDS Church has not apologized for its race-based policies and former teachings.[44][45]

See also

[edit]- Black Mormons

- Black people and priesthood (LDS)

- Criticism of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Genesis Group

- Proclamations of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles

Notes

[edit]- ^ There were a handful of exceptions to this rule, such as some descendants of Elijah Abel, the first black Latter-day Saint to hold priesthood office. See Newell G. Bringhurst (2006), "The 'Missouri Thesis' Revisited: Early Mormonism, Slavery, and the Status of Black People" in Newell G. Bringhurst and Darron T. Smith, Black and Mormon (Urbana: University of Illinois Press) p. 30

- ^ Mark E. Petersen was in Ecuador on an assignment and Delbert L. Stapley was in the hospital receiving medical care.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Prince & Wright (2005), p. 73.

- ^ Kimball (2005), p. 227.

- ^ Prince & Wright (2005), p. 97.

- ^ a b Peggy Fletcher Stack (December 16, 2013). "Mormon church traces black priesthood ban to Brigham Young". The Salt Lake Tribune.

- ^ a b c Bush, Lester E. Jr; Armand L. Mauss, eds. (1984). Neither White Nor Black: Mormon Scholars Confront the Race Issue in a Universal Church. Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books. ISBN 0-941214-22-2. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009.

- ^ "Black History Timeline". Retrieved April 14, 2016.

- ^ Collisson, Craig. "The BSU takes on BYU and the UW Athletics Program, 1970". Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. Retrieved April 14, 2016.

- ^ Bringhurst, Newell. Saints, Slaves, and Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People Within Mormonism. p. 185.

- ^ Prince, Gregory. David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism.

- ^ Quinn, D. Michael (1997). The Mormon Hierarchy: Extensions of Power. Signature Books. p. 14. ISBN 9781560850601 – via Google Books.

- ^ Grover, Mark. "Religious Accommodation in the Land of Racial Democracy: Mormon Priesthood and Black Brazilians" (PDF). Dialogue. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ Grover, Mark L. (Spring 1990), "The Mormon Priesthood Revelation and the São Paulo Brazil Temple" (PDF), Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 23 (1): 39–53, doi:10.2307/45225842, JSTOR 45225842, S2CID 254321222

- ^ Bush, Lester E. (1973). "Mormonism's Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview" (PDF). Dialogue. 8 (1). University of Illinois Press.

- ^ Kimball, Edward (2008). "Spencer W. Kimball and the Revelation on Priesthood". BYU Studies. 47. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ^ Wright, Eval (1977). A History of the South African Mission.

- ^ a b Prince & Wright 2005

- ^ Grover, Mark. "Religious Accommodation in the Land of Racial Democracy: Mormon Priesthood and Black Brazilians" (PDF). Dialogue. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ Horowitz, Jason (February 28, 2012). "The Genesis of a church's stand on race". Washington Post. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ Kimball (2005), p. 213.

- ^ a b Kimball (2005), p. 216.

- ^ Kimball (2005), p. 219.

- ^ Kimball (2005), p. 220.

- ^ Prince, Gregory A. (2016). Leonard Arrington and the writing of Mormon history. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. p. 324. ISBN 978-1-60781-479-5.

- ^ a b c d Kimball (2005), p. 221.

- ^ Kimball (2005), p. 222–24.

- ^ McConkie, Bruce R. (June 30, 1978). "The Receipt of the Revelation Offering the Priesthood to Men of All Races and Colors". Kimball Papers. cited in Kimball (2005:222) and McConkie (2003:373–79).

- ^ Kimball (2005), p. 222.

- ^ Hinckley, Gordon B. (October 1988). "Priesthood Restoration"". Ensign.

- ^ Kimball (2005), p. 231.

- ^ a b c "Official Declaration 2". Doctrine and Covenants. LDS Church.

- ^ Bates, Irene M. (1993). "Patriarchal Blessings and the Routinization of Charisma" (PDF). Dialogue. 26 (3). Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ^ Grover, Mark. "Religious Accommodation in the Land of Racial Democracy: Mormon Priesthood and Black Brazilians" (PDF). Dialogue. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ Stuart, Joseph (June 8, 2017). "Patriarchal Blessings, Race, and Lineage: History and a Survey". By Common Consent, a Mormon Blog. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ^ McConkie, Bruce R. (August 18, 1978). All Are Alike Unto God (Speech). A SYMPOSIUM ON THE BOOK OF MORMON, The Second Annual Church Educational System Religious Educator's Symposium. BYU,

as found in: McConkie, Bruce R. (2006), I believe: a retrospective of twelve firesides and devotionals, Brigham Young University, 1973-1985, Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, ISBN 0-8425-2647-1 - ^ "New policy occasions church comment". The Times-News. Associated Press. June 9, 1988.

AP: Was the ban on ordaining blacks to the priesthood a matter of policy or doctrine? ... OAKS: I don't know that it's possible to distinguish between policy and doctrine in a church that believes in continuing revelation and sustains its leader as a prophet. ... I'm not sure I could justify the difference in doctrine and policy in the fact that before 1978 a person could not hold the priesthood and after 1978 they could hold the priesthood. AP: Did you feel differently about the issue before the revelation was given? OAKS: I decided a long time ago, 1961 or 2, that there's no way to talk about it in terms of doctrine, or policy, practice, procedure. All of those words just lead you to reaffirm your prejudice, whichever it was.

- ^ Jacobson, Cardell (1992). "Doctrine and Covenants: Official Declaration—2". In Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.). Encyclopedia of Mormonism. New York: Macmillan Publishing. pp. 423–424. ISBN 0-02-879602-0. OCLC 24502140.

- ^ Tanner, N. Eldon (November 1978), "Revelation on Priesthood Accepted, Church Officers Sustained", Ensign: 16.

- ^ Woodford, Robert J. (December 1984), "The Story of the Doctrine and Covenants", Ensign: 32.

- ^ Sections 137 and 138 of the Doctrine and Covenants were added to the D&C in 1981; however, these texts had been part of the canon in the Pearl of Great Price since 1976:

◌ Hartshorn, Leon R. (1992). "Doctrine and Covenants: Sections 137–138". In Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.). Encyclopedia of Mormonism. New York: Macmillan Publishing. p. 423. ISBN 0-02-879602-0. OCLC 24502140.

◌ Tanner, N. Eldon (May 1976), "The Sustaining of Church Officers", Ensign: 18. - ^ Doctrine and Covenants, Student Manual: Religion 324 and 325 (PDF) (2nd ed.), Salt Lake City, Utah: Church Educational System, LDS Church, 2001, p. 364.

- ^ See, e.g.: "Chapter Ten: The Worldwide Church", Our Heritage: A Brief History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah: LDS Church, 1996, pp. 120–131.

- ^ "Gospel Topics Essays: Race and the Priesthood". LDS Church.

- ^ "President Oaks' Full Remarks from the LDS Church's 'Be One' Celebration" (Press release). Church News. June 1, 2018.

- ^ Wood, Benjamin (May 17, 2018). "No, the Mormon church did not apologize for having a history of racism; hoaxer says he meant fake message to spark discussion". The Salt Lake Tribune.

- ^ Riess, Jana (July 19, 2019). "Will the Mormon president apologize to the NAACP for the church's past racism?". Religion News Service.

Works cited

[edit]- Kimball, Edward L.; Kimball, Andrew E. Jr. (1977). Spencer W. Kimball. Salt Lake City: Bookcraft. ISBN 0-88494-330-5.

- Kimball, Edward L. (2005). Lengthen Your Stride: The Presidency of Spencer W. Kimball. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book. ISBN 1-59038-457-1.

- McConkie, Joseph Fielding (2003). The Bruce R. McConkie Story: Reflections of a Son. Deseret Book. ISBN 1-59038-205-6.

- Prince, Gregory A.; Wright, Wm. Robert (2005). David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0-87480-822-7.

Sources

[edit]- Brooks, Joanna (2020). Mormonism and White Supremacy: American Religion and the Problem of Racial Innocence. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190081768.

- Grover, Mark L. (Autumn 1984). "Religious Accommodation in the Land of Racial Democracy: Mormon Priesthood and Black Brazilians". Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 17 (3): 22–34. doi:10.2307/45227936. JSTOR 45227936.

- Grover, Mark L. (Spring 1990). "The Mormon Priesthood Revelation and the São Paulo, Brazil Temple". Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 23 (1): 39–53. doi:10.2307/45225842. JSTOR 45225842.

- Harris, Matthew L.; Bringhurst, Newell G., eds. (2015). The Mormon Church and Blacks: A Documentary History. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03974-4.

- Harris, Matthew L. (2020). "Confronting and Condemning "Hard Doctrine," 1978–2013". Mormon Studies Review. 7: 21–28. doi:10.5406/mormstudrevi.7.2020.0021.

- Harris, Matthew L. (2024). Second-class Saints: Black Mormons and the Struggle for Racial Equality. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197695715.

- Hudec, Amy Moff (2015). "Mormons and Race". In Stone, John; Dennis, Rutledge M.; Rizova, Polly S.; Smith, Anthony D.; Hou, Xiaoshuo (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Nationalism. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1002/9781118663202.wberen256. ISBN 9781405189781.

- Mauss, Armand L. (2003). All Abraham's Children: Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-02803-8.

- McDannell, Colleen (2020). "Global Mormonism: A Historical Overview". In Shepherd, R. Gordon; Shepherd, A. Gary; Cragun, Ryan T. (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Global Mormonism. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 3–34. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-52616-0_1. ISBN 978-3-030-52615-3.

- Park, Benjamin E. (2024). American Zion: A New History of Mormonism. Liveright. ISBN 978-1-63149-865-7.

- Prince, Gregory A. (2020). "The Evolving Ecclesiastical Organization of an International Lay Church". In Shepherd, R. Gordon; Shepherd, A. Gary; Cragun, Ryan T. (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Global Mormonism. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 35–56. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-52616-0_2. ISBN 978-3-030-52615-3.

- Rees, Robert A. (Summer 2023). "Truth and Reconciliation: Reflections on the Fortieth Anniversary of the LDS Church's Lifting the Priesthood and Temple Restrictions for Black Mormons of African Descent". Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 56 (2): 55–83. doi:10.5406/15549399.56.2.05.

- Rosetti, Cristina (Spring 2022). "Not Until the Millennium: 1978 and Fundamentalist Whitelash". American Religion. 3 (2): 51–68. doi:10.2979/amerreli.3.2.04.

Further reading

[edit]- Walch, Tad (June 8, 2014), "LDS blacks, scholars cheer church's essay on priesthood", Deseret News, archived from the original on June 12, 2014

External links

[edit]- A Work in Progress: The Latter-day Saint Struggle with Blacks and the Priesthood – Seth Payne at mormonstudies.net

- Official Declaration 2 – official text found in the Doctrine and Covenants at churchofjesuschrist.org

- "Gospel Topics: Race and the Priesthood", churchofjesuschrist.org, LDS Church

- 1978 in Christianity

- 1978 in Utah

- Doctrine and Covenants

- History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Mormonism and race

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Africa

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Brazil

- 20th-century Mormonism

- June 1978

- Revelation in Mormonism

- African-American history of Utah

- Post–civil rights era in African-American history