Como

Como

Còmm (Lombard) | |

|---|---|

| Città di Como | |

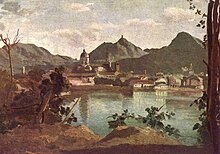

View of Como from Baradello Castle | |

| Coordinates: 45°49′0″N 9°5′0″E / 45.81667°N 9.08333°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Lombardy |

| Province | Como (CO) |

| Roman foundation | 196 BC |

| Frazioni | Albate, Borghi, Breccia, Camerlata, Camnago Volta, Civiglio, Garzola, Lora, Monte Olimpino, Muggiò, Ponte Chiasso, Prestino, Rebbio, Sagnino, Tavernola |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Alessandro Rapinese (since 27 June 2022) (Ind.) |

| Area | |

• Total | 37.14 km2 (14.34 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 201 m (659 ft) |

| Population (31 October 2022)[2] | |

• Total | 84,250 |

| • Density | 2,300/km2 (5,900/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Comaschi |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 22100 |

| Dialing code | 031 |

| Patron saint | Saint Abbondio |

| Saint day | 31 August |

| Website | Official website |

Como (Italian: [ˈkɔːmo] ⓘ,[3][4] locally [ˈkoːmo] ⓘ;[3] Comasco: Còmm [ˈkɔm],[5] Cómm [ˈkom] or Cùmm [ˈkum];[6] Latin: Novum Comum) is a city and comune (municipality) in Lombardy, Italy. It is the administrative capital of the Province of Como.

Its proximity to Lake Como and to the Alps has made Como a tourist destination, and the city contains numerous works of art, churches, gardens, museums, theatres, parks, and palaces: the Duomo, seat of the Diocese of Como; the Basilica of Sant'Abbondio; the Villa Olmo; the public gardens with the Tempio Voltiano; the Teatro Sociale; the Broletto or the city's medieval town hall; and the 20th-century Casa del Fascio.[7]

Como was the birthplace of many historical figures, including the poet Caecilius mentioned by Catullus in the first century BCE,[8][9] writers Pliny the Elder and Pliny the Younger, Pope Innocent XI, scientist Alessandro Volta,[10] and Cosima Liszt, second wife of Richard Wagner and long-term director of the Bayreuth Festival, and Antonio Sant'Elia (1888–1916), a futurist architect and a pioneer of the modern movement.[citation needed]

History

[edit]

Ancient history

[edit]The hills surrounding the current location of Como were inhabited, since at least the Iron Age, by a Celtic tribe known as the Orobii, who also, according to Pliny the Elder and modern scholars, had relations with the Ancient Ligurians,[11][12] a people very similar to the Celts. Remains of settlements are still present on the wood-covered hills to the southwest of town, around the area of the modern town's district of Rebbio. In the areas of the districts of Breccia, Prestino and the neighbouring towns of San Fermo della Battaglia and Cavallasca there were also settlements of the Golasecca Culture,[13] built in the Iron Age. Later, a second Celtic migration brought the Gaulish peoples in the area of Como, especially the tribe of the Insubres.[14]

Around the first century BC, the territory became subject to the Romans. The town centre was situated on the nearby hills, but it was then moved to its current location by order of Julius Caesar, who had the swamp near the southern tip of the lake drained and laid the plan of the walled city in the typical Roman grid of perpendicular streets. The newly founded town was named Novum Comum and had the status of municipium. In September 2018, Culture Minister Alberto Bonisoli announced the discovery of several hundred gold coins in the basement of the former Cressoni Theater (Teatro Cressoni) in a two-handled soapstone amphora, coins struck by emperors Honorius, Valentinian III, Leo I the Thracian, Antonio and Libius Severus dating to 474 AD.[15]

Early Middle Ages

[edit]After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the history of Como followed that of the rest of Lombardy, being occupied by the Goths, the Byzantines, and later the Langobards. The Langobards were a significant people in the region. Originating in Scandinavia, this Germanic group arrived in the Po Valley in 568, led by King Alboin. The Langobards established the Lombard Kingdom, which initially encompassed only modern-day Northern Italy, but later expanded to include Tuscany, Umbria, and portions of Southern Italy. Under Lombard rule, Como continued to flourish, particularly due to the reconstruction of Queen Theudelind's road, which connected Germany and the Italian Peninsula, providing the town with strategic access to commerce.[16] In 774, Como surrendered to the invading Franks led by Charlemagne and subsequently became a center of commercial exchange.[17]

Communal Era

[edit]The Commune of Como likely originated in the 11th century as an "association of prestigious families on a treaty basis," bound by an oath of adhesion to the commune, which was renewed periodically in front of municipal authorities until the 1200s, and later in the presence of the mayor. Despite resistance from parts of the feudal nobility of the diocese, this pact quickly extended to the entire free male population of the town. This expansion aimed to strengthen the political independence of Como and its diocese, especially from neighboring Milan, and to affirm the sovereignty of the bishop of Como. The bishop soon became the de facto "head of state", while an assembly of citizens convened in the "Broletto" (Town Hall), called "Brolo". This assembly consisted of representatives of the local nobility, known as consuls, and later included representatives of the guilds. The Commune had a set of laws and conventions that regulated urban activities, commerce, agriculture, fishing, hunting, law enforcement, and taxation.[18]

The first explicit written mention of the Commune of Como dates back to 1109. Initially, the deliberative assembly of the commune was likely the plenary assembly. In the early 12th century, the role of this assembly was assumed by the council (or "Credenza"), known after 1213 as the "General council" or "Bell council". From the second half of the 13th century, this assembly was divided into a large and a small council. Starting in 1109, the communal organization included an executive body called the "collegial magistracy of the consuls". Before 1172, this body was divided into two institutions: the consuls of justice and the consuls of the municipality. In the early 13th century, the latter were replaced by the podestà, who had broader special powers in criminal matters.[19]

The territory of the Commune extended beyond the town of Como itself, encompassing the entire diocese, which included most of present-day Province of Como, modern-day Canton of Ticino, Valtellina, Valchiavenna, and Colico.[20][21] Thanks to its strategic position on Lake Como and the important Road of Queen Theudelind, which linked the Italian Peninsula with Germany: the heart of the Holy Roman Empire, Como quickly became a wealthy and powerful town.[22]

During this period of growth, Como and Milan quickly became rivals. The Commune of Milan experienced significant population growth but lacked strategic communication routes.[23] Consequently, Milan planned to conquer neighboring territories to gain access to their strategic positions. Tensions first arose over the County of Seprio, as both communes sought control of the area.[23] Meanwhile, Milan acted aggressively against other Lombard towns, leading to the outbreak of the war of Lodi when soldiers from Lodi, Pavia, and Cremona attacked Tortona, an ally of Milan. In this conflict, Milan, supported by Crema and Tortona, fought against the communes of Lodi, Pavia, and Cremona, ultimately achieving a significant victory that established Milan as the dominant power in Lombardy.[24][25]

This left the Commune of Como as Milan's only remaining rival. Tensions escalated when Emperor Henry IV appointed Landolfo da Carcano, who sympathized with Milan, as the bishop of Como. In response, the people of Como elected Guido Grimoldi as their bishop and exiled Landolfo. Despite his exile, Landolfo continued to interfere in Como's affairs, prompting the town to besiege his castle under the leadership of consul Adamo del Pero. Landolfo was captured and imprisoned, igniting a crisis between Como and Milan, as Milanese soldiers had defended Landolfo's castle.

This conflict led to the Decennial War between Como and Milan in 1118. The war is well-documented thanks to an anonymous poet who recorded the events in a poem titled "Liber Cumanus, sive de bello Mediolanensium adversus Comenses".[23] Initially, Como seemed to prevail due to smart tactics, but after the death of Guido Grimoldi, the tide turned, and Como lost the war in 1127. Milanese soldiers destroyed every building in Como, sparing only the churches.[26]

After the war, the Commune was forced to pay tribute to Milan.[27] However, this changed when Frederick Barbarossa came to power and restored Como's independence from Milan. The Comaschi avenged their defeat when Milan was destroyed in 1162. Frederick promoted the construction of several defensive towers and small castles around the town's limits, of which only the Baradello remains. He also assisted the town in rebuilding its defensive walls, most of which still survive today.

When the Guelph communes organized the Lombard League to oppose the Holy Roman Emperor, Como maintained its Ghibelline alignment. Frederick I Barbarossa formally recognized the Commune of Como with an imperial diploma in 1175 (Concession of Frederick I 1175), allowing the town to elect the mayors of the county. This was a reward for Como's defection from the Lombard League and its shared anti-Milan policy. Subsequent agreements in 1191 and 1216 saw Emperors Henry VI and Frederick II extend additional concessions to Como, similar to those made in the Peace of Constance to the cities participating in the League.

In 1281, Como adopted its first written legislative code, the "Statuta Consulum Iustitie et Negotiatorum", followed by a second code in 1296.[28]

The rise of Rusca/Rusconi family to power

[edit]

In the second half of the 12th century, the Rusca family (also known as Rusconi) began to gain prominence in the town of Como. The Rusca were a noble family originating in Como in the 10th century. They led the Ghibelline faction in the town, with their principal rivals being the members of the Vitani family.

In 1182, Giovanni Rusca became a consul of the commune and was later appointed podestà of Milan in 1199, thanks to his abilities during a peace treaty with the rival city. Between 1194 and 1198, he was joined by two other relatives, Adamo and Loterio, who also became consuls of Como. The Rusca quickly became the most influential family in Como, with several members attempting to establish a lordship over the town with varying degrees of success.[29]

Loterio Rusca was the first to attempt this goal. He was acclaimed "Lord of the People" in 1276 and, with the trust of the Comaschi, he began his rise to power. However, he faced resistance from the bishop of Como, Giovanni degli Avvocati, who was consequently exiled. Giovanni was hosted by the Visconti of Milan, providing Ottone Visconti with a pretext to start a new war against Como. Unexpectedly, Loterio prevailed and signed a favorable peace treaty with Milan in the town of Lomazzo. Milan was forced to recognize Loterio as the ruler of their rival town and return the town of Bellinzona to Como.[29]

Thanks to this success, the family secured titles such as Lords of Como, Bellinzona, Chiavenna, and Valtellina, as well as Counts of Locarno, Lugano, and Luino. Following Loterio's death, the next notable family member was Franchino I Rusca, who established a personal lordship over Como and its territories and became an imperial vicar.

In 1335, a new war between Como and Milan broke out due to the expiration of conditions established in Lomazzo. This time, under the leadership of Azzone Visconti, Milan won the war and Como was annexed to the Duchy of Milan. The people of Como sought to regain their administrative freedom, and an opportunity arose in 1402 when Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan, died. Franchino II Rusca led a rebellion against the Milanese, which ended in 1412 when his son, Loterio IV Rusca, gained the title of Lord of Como and drove out the Milanese occupiers. However, this did not end the political unrest, and a period of conflicts and massacres ensued until Como once again fell under the control of Filippo Maria Visconti, becoming part of the Duchy of Milan in 1416.

At the Duke's death, Como reclaimed its independence, and in 1447, the "Republic of Saint Abundius" was founded.[29][30] In January 1449, Francesco Sforza, who claimed the title of Duke of Milan (though the city was under the control of the Ambrosian Republic), sent Giuseppe Ventimiglia to attack Como. He was repelled by the citizens led by Giovanni della Noce, forcing him to retreat to Cantù, in Brianza. Monzone assisted the Rusca against the Vitani, who were Guelphs allied with the Milanese, ultimately defeating them with Ghibelline forces. In April 1449, Ventimiglia attacked Como again, and in January 1450, he unsuccessfully attacked the Ambrosian garrisons in Monza, intended to reunite with the Venetians of Colleoni to support Milan against Sforza. These events, known as the Battles of Cantù and Asso, culminated in March 1450 when Como was defeated following the fall of the Ambrosian Republic, due to exhaustion and lack of resources. Como was definitively subjected to the reconstituted Duchy of Milan under Francesco Sforza, who in 1458 profoundly reformed the Statutes of Como.[29]

Modern Era

[edit]Subsequently, the history of Como followed that of the Duchy of Milan, through the French invasion and the Spanish domination, until 1714, when the territory was taken by the Austrians. Napoleon descended into Lombardy in 1796 and ruled it until 1815, when the Austrian rule was resumed after the Congress of Vienna. By 1848, the population had reached 16,000.[31] In 1859, with the arrival of Giuseppe Garibaldi, the town became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Italy under the House of Savoy.

20th century

[edit]The Rockefeller fountain that today stands in the Bronx Zoo in New York City was once in the main square (Piazza Cavour) by the lakeside. It was bought by William Rockefeller in 1902 for Lire 3,500 (the estimated equivalent then of $637).[32]

At the end of World War II, after passing through Como on his escape towards Switzerland, Benito Mussolini was taken prisoner and then shot by partisans in Giulino di Mezzegra, a small town on the north shores of Lake Como.

21st century

[edit]In 2010, a motion by members of the nationalist Swiss People's Party was submitted to the Swiss parliament requesting the admission of adjacent territories to the Swiss Confederation; Como (and its province) is one of these.[33][34][35]

Geography and Climate

[edit]Situated at the southern tip of the south-west arm of Lake Como, the city is located 40 kilometres (25 mi) north of Milan; the city proper borders Switzerland and the communes of Blevio, Brunate, Capiago Intimiano, Casnate con Bernate, Cernobbio, Grandate, Lipomo, Maslianico, Montano Lucino, San Fermo della Battaglia, Senna Comasco, Tavernerio, and Torno, and the Swiss towns of Chiasso and Vacallo. Nearby major cities are Varese, Lecco, and Lugano.

Climate

[edit]According to the Köppen climate classification, Como has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa); until the late 20th century winters used to be quite cold, with average daily temperatures well below freezing;[36] recently, occasional periods of frost from the Siberian Anticyclone have been recorded; however, due to global warming average temperatures in winter have gradually risen since the turn of the 21st century, reaching a record high of 21 degrees Celsius (70 °F) on 27 January 2024;[37][38] spring and autumn are well marked and pleasant, while summer can be quite hot and sultry. Wind is uncommon although sudden bursts of foehn have been registered in different occasions. Pollution levels rise significantly in winter when cold air clings to the soil. Rain is more frequent during spring; summer is subject to thunderstorms and occasionally violent hailstorms.[39]

| Climate data for Como (1989–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

9.8 (49.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

18.7 (65.7) |

22.9 (73.2) |

26.9 (80.4) |

29.4 (84.9) |

28.7 (83.7) |

23.3 (73.9) |

17.4 (63.3) |

11.6 (52.9) |

7.7 (45.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.9 (39.0) |

5.4 (41.7) |

9.7 (49.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

17.6 (63.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.4 (74.1) |

18.7 (65.7) |

13.7 (56.7) |

8.3 (46.9) |

4.4 (39.9) |

13.7 (56.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.2 (32.4) |

1.1 (34.0) |

4.7 (40.5) |

8.1 (46.6) |

12.3 (54.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.1 (64.6) |

14.1 (57.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

1.0 (33.8) |

9.1 (48.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 70 (2.8) |

75 (3.0) |

115 (4.5) |

105 (4.1) |

160 (6.3) |

135 (5.3) |

85 (3.3) |

135 (5.3) |

115 (4.5) |

125 (4.9) |

130 (5.1) |

65 (2.6) |

1,315 (51.7) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 95 |

| Source: Climi e viaggi[40] | |||||||||||||

Government

[edit]The legislative body of the Italian comuni is the City Council (Consiglio Comunale); in Como, it comprises 32 councillors elected every five years with a proportional system, at the same time of the mayoral elections. The executive body is the City Committee (Giunta Comunale), composed of 9 assessori each overseeing a specific ministry, that is nominated and presided over by a directly elected Mayor (Sindaco). The mayor of Como since 27 June 2022, is Alessandro Rapinese, an independent leading an alliance bearing his name (Rapinese Sindaco), unaffiliated with any official political party.

Administrative subdivisions

[edit]

Como is divided into these frazioni (roughly equivalent to the anglocentric ward):

- Albate – Muggiò – Acquanera

- Lora

- Prestino – Camerlata – Breccia – Rebbio

- Camnago Volta

- City Center – West Como

- Borghi

- North Como – East Como

- Monte Olimpino – Ponte Chiasso – Sagnino – Tavernola

- Garzola – Civiglio

Main sights

[edit]Churches

[edit]

- Como Cathedral: Construction began in 1396 on the site of the previous Romanesque church of Santa Maria Maggiore. The façade was built in 1457, with the characteristic rose window and a portal flanked by two Renaissance statues of the famous comaschi Pliny the Elder and Pliny the Younger. The construction was finished in 1740. The interior is on the Latin cross plan, with Gothic nave and two aisles divided by piers, while the transept wing and the relative apses are from the Renaissance age. It includes a carved 16th-century choir and tapestries on cartoons by Giuseppe Arcimboldi. The dome is a rococo structure by Filippo Juvarra. Other artworks include 16th–17th-century tapestries and 16th-century paintings by Bernardino Luini and Gaudenzio Ferrari.

- San Fedele, a Romanesque church erected around 1120 over a pre-existing central plan edifice. The original bell tower was rebuilt in modern times. The main feature is the famous Door of St. Fedele, carved with medieval decorations.

- Sant'Agostino, built by the Cistercians in the early 14th century, heavily renovated in the 20th. The interior and adjoining cloister have 15th–17th-century frescoes, but most of the decoration is Baroque.

- Basilica of Sant'Abbondio, a Romanesque structure consecrated in 1095 by Pope Urban II. The interior, with a nave and four aisles, contains paintings dating to the 11th century and frescoes from the 14th.

- San Carpoforo (11th century, apse and crypt from 12th century). According to tradition, it was founded re-using a former temple of the God Mercury to house the remains of Saint Carpophorus and other local martyrs.

Secular buildings and monuments

[edit]- The ancient town hall, known as the Broletto

- Casa del Fascio, possibly Giuseppe Terragni's most famous work. It has been described as an early "landmark of modern European architecture".

- Monumento ai caduti (war memorial) by Giuseppe Terragni

- Teatro Sociale by Giuseppe Cusi in 1813[41]

- Villa Olmo, built from 1797 in neoclassicist style by the Odescalchi family. It housed Napoleon, Ugo Foscolo, Prince Metternich, Archduke Franz Ferdinand I, Giuseppe Garibaldi, and other eminent figures. It is now a seat for exhibitions.

- Monumental Fountain also known as "Volta's Fountain", a monument to Volta's battery; it was designed by architect Carlo Cattaneo and painter Mario Radice and is a 9 m-high (30 ft) cement combination of alternating spheres and rings. It is in the centre of Camerlata Square.

- Ancient walls (medieval)

- the Tempio Voltiano, a museum dedicated to Alessandro Volta, a famous Comasco engineer, physicist, and inventor

- the Life Electric, a modern sculpture made by Daniel Libeskind

- Castello Baradello, a small medieval castle overlooking the town and which is all that remains of the fortress constructed by Barbarossa c. 1158

Economy

[edit]The economy of Como, until the end of the 1980s, was traditionally based on industry; in particular, the city was world-famous for its silk manufacturers, and in 1972 its production exceeded that of China and Japan,[42][43] but since the mid-1990s increasing competition from Asia has significantly reduced profit margins and many small and mid-sized firms have gone out of business. As a consequence, manufacturing is no longer the economic driver, and the city has been absorbed into Milan's metropolitan area where it mainly provides workers to the service industry sector. A significant number of residents are employed in the nearby Swiss towns Lugano and Mendrisio, primarily in the industrial sector, health care services and in the hospitality industry;[44] the 30 km (19 mi) commute is beneficial as wages in Switzerland are notably higher. For these reasons, tourism has become increasingly important for the city's economy since the late 1990s, when local small businesses have gradually been replaced by bars, restaurants and hotels. With about 400 thousand overnight guests in 2023, Como was one of the most visited cities in Lombardy.[45]

The city and the lake have been chosen as the filming location for various recent popular feature films, and this, together with the increasing presence of celebrities such as Matt Bellamy who have bought lakeside properties,[46] has heightened the city's attractiveness and given a further boost to international tourism; since the early 2000s the city has become a popular "must-see" tourist destination in Italy.[47]

Demographics

[edit]The city of Como has seen its population increase until it peaked at almost 100,000 inhabitants in the 1970s, when manufacturing, especially the silk industry, was in its boom years. As production began to decline, the population tally decreased by almost 20,000 until the beginning of the 21st century, when the city saw its population grow again by more than six thousand units, generally due to increasing immigration from Asia, Eastern Europe and North Africa. As of January 2023, the population was 83,700 people of which 12,000 were resident aliens, that is, 14% of the total; the population distribution by origin was as follows:[48]

| Pos. | Origin | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Italy | 86% |

| 2 | Europe | 5.3% |

| 3 | Asia | 4.1% |

| 4 | Africa | 2.8% |

| 5 | America | 1.8% |

| 6 | Oceania | 0.02% |

Top 20 nationalities of resident aliens:

| Pos. | Citizenship | Residents |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1155 | |

| 2 | 947 | |

| 3 | 791 | |

| 4 | 656 | |

| 5 | 604 | |

| 6 | 578 | |

| 7 | 545 | |

| 8 | 498 | |

| 9 | 470 | |

| 10 | 426 | |

| 11 | 411 | |

| 12 | 364 | |

| 13 | 313 | |

| 14 | 301 | |

| 15 | 234 | |

| 16 | 233 | |

| 17 | 214 | |

| 18 | 168 | |

| 19 | 164 | |

| 20 | 151 |

Culture

[edit]Museums

[edit]In Como there are the following museums and exhibition centres:

- Museo Archeologico "P. Giovio" – archeological museum

- Garibaldi Museum (Como) – a museum dedicated to Giuseppe Garibaldi

- Tempio Voltiano – a museum devoted to Alessandro Volta's work

- Villa Olmo – various exhibitions

- Museo Didattico Della Seta – educational silk museum

- Museo Liceo classico "A. Volta" – scientific museum

- Pinacoteca Civica – paintings and artworks from the Carolingian to modern era housed in the 17th-century Palazzo Volpi

Cuisine

[edit]Polenta is a popular dish in Como, and was traditionally eaten for meals in wintertime. It is obtained by mixing and cooking corn flour and buckwheat. It is usually served with meat, game, cheese and sometimes fish; in fact, Polenta e Misultin (Alosa agone) is served in the restaurants in the Lake Como area.

A traditional dish is the Risotto con Filetti di Pesce Persico or simply Risotto al Pesce Persico (European perch filet risotto), a fish grown in Lake Como, prepared with white wine, onion, butter and wheat.[49]

Palio del Baradello

[edit]In Como, a medieval festival called Palio del Baradello takes place annually.[50]

The first edition took place in 1981.[51] The event is organized every year to narrate to the citizens and tourists the events that happened in 1159 when the town hosted the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and aided him in his fight against the rebel communes in Lombardy. The Emperor restored Como's former freedom, which was lost in a ten-year-long war against Milan. Together, the Ghibelline communes and the emperor defeated Milan.

These pivotal moments for the town are celebrated by the medieval festival, where actors portray the main characters: Frederick Barbarossa, Henry the Lion, Beatrice of Burgundy, and Bishop Ardizzone, while citizens dress up in medieval attire.

During the Palio del Baradello, the town is divided into its historical wards called "Borghi" (in Lombard: "Burgh"[52]) Tavernola,[53] Quarcino,[54] Rebbio, Camerlata,[55] Cernobbio,[56] Cortesella[57] and Sant'Agostino.[58] The first day hosts the opening ceremony while in the following days the factions compete in different races to determine which district will win the year's edition.[59]

The final day of the festival consists of a grand parade where all the participants march across the town in medieval costumes, accompanied by animals, wagons, and replicas of siege engines, culminating in a ceremony where the emperor announces to the public which ward won the competition.

Symbology

[edit]Heraldry

[edit]The heraldic achievement of Como consists of a white cross on a red background. This symbol was used in the Middle Ages to represent the town's political faction, the Ghibellines. The first recorded mention of this emblem dates back to the decennial war between Como and Milan (1118–1127). An anonymous poet from Como described the coat of arms in his poem about the war as "rubra signa" (Latin: "red symbol") and "cum cruce alba" (Latin: "with a white cross").[60]

Later, the motto 'LIBERTAS' (Latin: 'Freedom') was added to the town's heraldic achievement. The oldest testament of this symbol comes from the year 1619 when the historian Francesco Ballarini wrote that the people of Como at the time were already using the motto in the town's coat of arms.[60] It is thought that this motto emerged when the town of Como was liberated from the Milanese occupation with the help of the Holy Roman emperor Frederick I Barbarossa. The motto was later censored when the town was conquered by the Visconti family in the 15th Century. It was restored when the town proclaimed its independence from the Lordship of Milan, but censored again as Milan regained control over Como. The motto was restored one last time after the unification of Italy, as otherwise the town's coat of arms would have been too similar to the arms of the House of Savoy, which were included in the heraldic achievement of the newly born Kingdom of Italy.

Curiously, the coat of arms of Como is often represented with a curvature and surrounded by floral elements. The crown is another important element of the heraldic achievement. A crown appeared in the coats of arms of Como reported on some municipal posters in 1796. On 9 November 1819, Francis I of Austria, Emperor of the Austria, recognized Como as a "Royal Town": that is when the crown (five-pointed and studded with gems) officially entered the coat of arms. In the version that came in 1859, the crown is topped with six gold fleurs-de-lis (only the front three visible).[60]

Flags

[edit]Throughout history, Como has used the Cross of Saint John as its flag: a white cross over a red field. Around the 12th Century, the city started to fly a version of this banner that included the word "LIBERTAS" in the bottom right corner, as represented in the town's heraldic achievement. This flag can be seen displayed at the town hall (Palazzo Cernezzi).

Transportation

[edit]Rail

[edit]The Servizio Ferroviario Regionale (Regional Railway Service) connects Como by train to other major cities in Lombardy. Services are provided by Trenord through two main stations: Como San Giovanni and Como Nord Lago. There are five more urban stations (Albate-Camerlata, Albate-Trecallo, Como Borghi, Como Camerlata and Grandate-Breccia).

Como San Giovanni is also a stop on the main north–south line between Milan Centrale and Zürich HB and Basel SBB. Intercity and EuroCity trains stop at this station, which makes Como very accessible from the European Express train network.

The lakeside funicular connects the centre of Como with Brunate, a small village (1,800 inhabitants) on a mountain at 715 m (2,346 ft) above sea level.

Buses and taxis

[edit]The local public transport network comprises 11 urban (within city limits) lines and 'extra-urban' (crossing city limits) (C) lines connecting Como with most of its province centres. They are provided by ASF Autolinee.

Ferrovie Nord Milano also provides other bus lines connecting Como to Varese in substitution of the original railway line that was dismissed in the 1960s.

Taxi service is provided by the Municipality of Como.

Ship transport

[edit]The boats and hydrofoils (aliscafi) of Navigazione Laghi connect the town with most of the villages sitting on the shores of the lake.

Airports

[edit]Nearby airports providing scheduled flights are Malpensa International Airport, Milano Linate and Orio al Serio International Airport; Lugano Airport, in Switzerland, mainly schedules regional flights within Switzerland, charter flights to nearby countries[61] and caters to private aircraft operations.

Aero Club

[edit]

Como is home to the oldest seaplane operation in the world,[62] the Aero Club Como (ICAO code LILY),[63] with a fleet consisting of four seaplanes, used for flight training and local tour flights and four classic seaplanes of historical interest, a 1961 Cessna O-1 Bird Dog, a 1946 Republic RC-3 Seabee a 1947 Macchi M.B.308 idro and a perfectly restored 1935 Caproni Ca.100.[64][65] A hangar right next to the lake houses the club's fleet and is also used for aircraft maintenance and servicing.

Education and health

[edit]Como is home to numerous high schools, the Conservatory of music "Giuseppe Verdi", the Design school "Aldo Galli", the University of Insubria and a branch campus of the Politecnico di Milano.

In Como there are three major hospitals: Ospedale Sant'Anna, Ospedale Valduce and Clinica Villa Aprica.

Sports

[edit]Notable sports clubs are the ASDG Comense 1872 basketball team, a two-time winner of the FIBA EuroLeague Women, and Como 1907, a football team. There are also numerous recreational activities available for tourists such as pedal boating, fishing, walking and seaplane rentals. Como also hosts a prestigious clay-court tennis tournament every year, the Città di Como Challenger, which attracts many of the world's top players who are not involved in the concurrent US Open. Many players have testified that they much prefer playing in the relaxed and friendly Como environs than the hustle and bustle of Flushing Meadows–Corona Park. [citation needed]

International relations

[edit] Fulda, Germany, since 1960

Fulda, Germany, since 1960 Tokamachi, Japan, since 1975

Tokamachi, Japan, since 1975 Nablus, Palestine, since 1998

Nablus, Palestine, since 1998 Netanya, Israel, since 2004[67]

Netanya, Israel, since 2004[67]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Demo-Geodemo. – Maps, Population, Demography of ISTAT – Italian Institute of Statistics". Archived from the original on 21 November 2004. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ a b Migliorini, Bruno; Tagliavini, Carlo; Fiorelli, Piero. Tommaso Francesco Borri (ed.). "Dizionario italiano multimediale e multilingue d'ortografia e di pronunzia". dizionario.rai.it. Rai Eri. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Canepari, Luciano. "Dizionario di pronuncia italiana online". dipionline.it. Archived from the original on 9 October 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Carlo Bassi, Grammatica essenziale del "dialètt de Còmm", Como, Edizioni della Famiglia Comasca, 2014

- ^ Libero Locatelli, Piccola grammatica del dialetto comasco, Como, Famiglia Comasca, 1970, p. 6.

- ^ "Como, Italy. The best things to do in Como city". Lake Como Travel. 8 May 2019. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ John Hazel (2001). Who's who in the Roman World. Psychology Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-415-22410-9.

- ^ "Catullus". Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ^ "Alessandro Volta". Corrosion-doctors.org. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ Peron, Ettore Maria (July 2017). Storia di Como [History of Como] (First ed.). Pordenone: Edizioni Biblioteca dell'immagine (published 2017). p. 4. ISBN 9788863912685.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Luraschi, Giorgio (1999). Storia di Como Antica [Ancient History of Como] (Second ed.). Como: Edizioni New Press. p. 5. ISBN 8895383834.

- ^ Luraschi, Giorgio (1999). Storia di Como Antica [Ancient History of Como] (Second ed.). Como: Edizioni New Press. p. 5. ISBN 8895383834.

- ^ Peron, Ettore Maria (July 2017). Storia di Como [History of Como] (First ed.). Pordenone: Edizioni Biblioteca dell'Immagine (published 2017). p. 7. ISBN 9788863912685.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Hundreds Of Roman Gold Coins Found In Theater Basement Archived 12 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Shannon Van Sant, NPR, 2018-09-10

- ^ Zanella, Antonio (16 October 1991). Paolo Diacono, La storia dei longobardi [Paul the Deacon, the History of the Langobards]. Rizzoli. ISBN 978-8817168243.

- ^ "Beni culturali".

- ^ "Piano delle regole" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ "Comune di Como sec. XI - 1757". Lombardia Beni Culturali. Archived from the original on 12 November 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ Almini, Saverio (19 January 2005). "Lombardia Beni Culturali: Diocesi di Como" [Lombardy cultural heritage: the Diocese of Como]. Lombardia Beni Culturali (History page of a Regional Government's Heritage department) (in Italian).

- ^ Bergamaschi, Mario (January 2013). Il Cumano Cronaca della guerra decennale tra Como e Millano 1118-1127 [The Cumano, Cronicles of the 10-Years War between Como and Milan 1118-1127] (in Italian). Alessandro Dominioni Editore. pp. 29–36. ISBN 9788887867459.

- ^ Bergamaschi, Mario (January 2013). Il Cumano Cronaca della Guerra Decennale tra Como e Milano 1118-1127 [The Cumano, cronicle of the 10-Years War between Como and Milan 1118-1127]. Gorgonzola: Alessandro Dominioni Editore. pp. 15–19. ISBN 9788887867459.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c Bergamaschi, Mario (January 2013). Il Cumano Cronoca della guerre decennale tra Como e Milano 1118-1127 [The Cumano, Cronicles of the decennial war between Como and Milan 1118-1127] (in Italian). Alessandro Dominioni Editore. pp. 51–63. ISBN 9788887867459.

- ^ Corio, Bernardino (1855). Storia di Milano [History of Milan] (in Italian). Milan: Francesco Colombo. p. 127.

- ^ Giulini, Giorgio (1855). Memorie spettanti alla storia, al governo ed alla descrizione della città, e della campagna di Milano, ne'secoli bassi [Memories relating to the history, government and description of the city and countryside of Milan in the early centuries] (in Italian) (3rd ed.). Milan: Francesco Colombo Librajo. pp. 3–25.

- ^ Bergamaschi, Mario (January 2013). Il Cumano Cronaca della guerra decennale tra Como e Milano 1118-1127 [The Cumano, Cronicle of the 10-Years War between Como and Milan 1118-1127] (in Italian). Alessandro Dominioni Editore. pp. 63–152. ISBN 9788887867459.

- ^ Bergamaschi, Mario (2013). Il Cumano. Cronaca della guerra decennale tra Como e Milano 1118-1127 [The Cumano. Chronicles of the Ten-Year War Between Como and Milan (1118-1127)]. Como: Alessandro Dominioni Editore. ISBN 9788887867459.

- ^ "Comune di Como, sec. XI - 1757 – Istituzioni storiche – Lombardia Beni Culturali". Archived from the original on 12 November 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Comune di Como, sec. XI - 1757 – Istituzioni storiche – Lombardia Beni Culturali". Archived from the original on 12 November 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ Alberto Artioli, Il duomo di Como: guida alla storia; restauri recenti, Storie d'arte, Como, NodoLibri, 1990.

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge Vol IV. London: Charles Knight. 1848. p. 811.

- ^ "Bronx Park Highlights". Archived from the original on 17 August 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ Maurisse, Marie (22 June 2010). "Quand un député suisse rêve d'annexer la Savoie". Le Figaro. Archived from the original on 24 June 2010. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ "SVP-Forderung: Vorarlberg soll Kanton werden". Der Standard. 21 June 2010. Archived from the original on 24 June 2010. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ Coen, Leonardo (22 June 2010). "L'ultima tentazione di Como: "Vogliamo diventare svizzeri"". La Repubblica. Archived from the original on 25 June 2010. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ "Historical Weather in February 1987 in Como". weatherspark.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "Historical Weather". weatherspark.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "Caldo Natale sul lago di Como, il termometro sfiora i 20 gradi: colpa del Foehn" (in Italian). informazione.it. 25 December 2023. Archived from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Nubifragio, raffiche di vento a 100 km/h, grandine come palline da golf" (in Italian). quicomo.it. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Clima - Como (Lombardia)". Climi e viaggi. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ "Il tetatro socilae di Come (in English)". Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ "Lake Como's Silk". lakecomotravel.com. 16 June 2019. Archived from the original on 13 December 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Tagliabue, John (10 April 1997). "Italian Silk Industry Upset By a New U.S. Trade Law". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ^ "Cross-border commuters". Admin.ch. Archived from the original on 19 November 2022. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ "Turismo a Como, i pernottamenti crescono del 28% rispetto al 2022" (in Italian). espansione TV. 22 September 2023. Archived from the original on 10 December 2023. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Muse's Matt Bellamy Lists Lake Como Condo". Variety. 16 May 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ "Best Places to Visit in Italy". US News. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Statistiche Istat". Istat. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Food and Culture Encyclopedia:Northern Italy". answers.com. Archived from the original on 4 June 2010. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ "Palio del Baradello di Como". Palio del Baradello di Como. Archived from the original on 4 March 2024. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Il Palio". Palio del Baradello di Como.

- ^ Bassi, Carlo (2019). Vocabolario del dialètt de Còmm [Dictionary of the dialect of Como] (in Italian) (2nd ed.). Como: Famiglia Comasca (published 2021). p. 246. ISBN 978-8897180678.

- ^ "Borgo di Tavernola". Palio del Baradello di Como. Archived from the original on 3 March 2024. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Borgo di Quarcino". Palio del Baradello di Como. Archived from the original on 3 March 2024. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Borgo di Camerlata". Palio del Baradello di Como.

- ^ "Comune di Cernobbio". Palio del Baradello di Como. Archived from the original on 3 March 2024. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Contrada della Cortesella". Palio del Baradello di Como. Archived from the original on 31 August 2024. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Borgo di Sant'Agostino". Palio del Baradello di Como. Archived from the original on 3 March 2024. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Le Gare". Palio del Baradello di Como. Archived from the original on 3 March 2024. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "Stemma comunale". Archived from the original on 31 August 2024. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Lugano Airport". Flightradar24. Archived from the original on 16 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "The World's Best Hotel Bars: Terrazza 241 In Lake Como, Italy". www.forbes.com. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ AIP Italia Archived 9 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine AD2 LILY

- ^ "The historic fleet". www.aeroclubcomo.com. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ "Aero Club Como". Archived from the original on 31 August 2024. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ "Città Gemelle". Comune di Como. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Netanya – Twin Cities". Netanya Municipality. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

Sources

[edit]External links

[edit]- Official website (in Italian and English)

- Official Tourism Portal

- Historical picture gallery and slideshow

- Official Tourist Board website (in Italian and English)

- Lake Como Navigation Company

- Official Virtual Tour

- A documentary about the Lake by Yann Arthus-Bertrand