Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale | |

|---|---|

Nightingale, c. 1860 | |

| Born | 12 May 1820 |

| Died | 13 August 1910 (aged 90) Mayfair, London, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Known for |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Hospital hygiene and sanitation, statistics |

| Institutions | |

| Signature | |

Florence Nightingale OM RRC DStJ (/ˈnaɪtɪŋɡeɪl/; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during the Crimean War, in which she organised care for wounded soldiers at Constantinople.[4] She significantly reduced death rates by improving hygiene and living standards. Nightingale gave nursing a favourable reputation and became an icon of Victorian culture, especially in the persona of "The Lady with the Lamp" making rounds of wounded soldiers at night.[5][6]

Recent commentators have asserted that Nightingale's Crimean War achievements were exaggerated by the media at the time, but critics agree on the importance of her later work in professionalising nursing roles for women.[7] In 1860, she laid the foundation of professional nursing with the establishment of her nursing school at St Thomas' Hospital in London. It was the first secular nursing school in the world and is now part of King's College London.[8] In recognition of her pioneering work in nursing, the Nightingale Pledge taken by new nurses, and the Florence Nightingale Medal, the highest international distinction a nurse can achieve, were named in her honour, and the annual International Nurses Day is celebrated on her birthday. Her social reforms included improving healthcare for all sections of British society, advocating better hunger relief in India, helping to abolish prostitution laws that were harsh for women, and expanding the acceptable forms of female participation in the workforce.

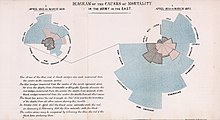

Nightingale was an innovator in statistics; she represented her analysis in graphical forms to ease drawing conclusions and actionables from data. She is famous for usage of the polar area diagram, also called the Nightingale rose diagram, which is equivalent to a modern circular histogram. This diagram is still regularly used in data visualisation.

Nightingale was a prodigious and versatile writer. In her lifetime, much of her published work was concerned with spreading medical knowledge. Some of her tracts were written in simple English so that they could easily be understood by those with poor literary skills. She was also a pioneer in data visualisation with the use of infographics, using graphical presentations of statistical data in an effective way.[7] Much of her writing, including her extensive work on religion and mysticism, has only been published posthumously.

Early life

Florence Nightingale was born on 12 May 1820 into a wealthy and well-connected British family at the Villa Colombaia,[9][10] in Florence, Tuscany, Italy, and was named after the city of her birth. Florence's older sister Frances Parthenope had similarly been named after her place of birth, Parthenope, a Greek settlement now part of the city of Naples. The family moved back to England in 1821, with Nightingale being brought up in the family's homes at Embley, Hampshire, and Lea Hurst, Derbyshire.[11][12]

Florence inherited a liberal-humanitarian outlook from both sides of her family.[7] Her parents were William Edward Nightingale, born William Edward Shore (1794–1874) and Frances ("Fanny") Nightingale (née Smith; 1788–1880). William's mother Mary (née Evans) was the niece of Peter Nightingale, under the terms of whose will William inherited his estate at Lea Hurst, and assumed the name and arms of Nightingale. Fanny's father (Florence's maternal grandfather) was the abolitionist and Unitarian William Smith.[13] Nightingale's father educated her.[12]

A BBC documentary reported that "Florence and her older sister Parthenope benefited from their father's advanced ideas about women's education. They studied history, mathematics, Italian, classical literature, and philosophy, and from an early age Florence, who was the more academic of the two girls, displayed an extraordinary ability for collecting and analysing data which she would use to great effect in later life."[7]

In 1838, her father took the family on a tour in Europe where she was introduced to the English-born Parisian hostess Mary Clarke, with whom Florence bonded. She recorded that "Clarkey" was a stimulating hostess who did not care for her appearance, and while her ideas did not always agree with those of her guests, "she was incapable of boring anyone." Her behaviour was said to be exasperating and eccentric and she had little respect for upper-class British women, whom she regarded generally as inconsequential. She said that if given the choice between being a woman or a galley slave, then she would choose the freedom of the galleys. She generally rejected female company and spent her time with male intellectuals. Clarke made an exception, however, in the case of the Nightingale family and Florence in particular. She and Florence were to remain close friends for 40 years despite their 27-year age difference. Clarke demonstrated that women could be equal to men, an idea that Florence had not learnt from her mother.[14]

Nightingale underwent the first of several experiences that she believed were calls from God in February 1837 while at Embley Park, prompting a strong desire to devote her life to the service of others. In her youth she was respectful of her family's opposition to her working as a nurse, only announcing her decision to enter the field in 1844. Despite the anger and distress of her mother and sister, she rejected the expected role for a woman of her status to become a wife and mother. Nightingale worked hard to educate herself in the art and science of nursing, in the face of opposition from her family and the restrictive social code for affluent young English women.[15]

As a young woman, Nightingale was described as attractive, slender, and graceful. While her demeanour was often severe, she was said to be very charming and to possess a radiant smile. Her most persistent suitor was the politician and poet Richard Monckton Milnes, but after a nine-year courtship, she rejected him, convinced that marriage would interfere with her ability to follow her calling to nursing.[15]

In Rome in 1847, she met Sidney Herbert, a politician who had been Secretary at War (1845–1846) who was on his honeymoon. He and Nightingale became lifelong close friends. Herbert would be Secretary of War again during the Crimean War when he and his wife would be instrumental in facilitating Nightingale's nursing work in Crimea. She became Herbert's key adviser throughout his political career, though she was accused by some of having hastened Herbert's death from Bright's disease in 1861 because of the pressure her programme of reform placed on him. Nightingale also much later had strong relations with academic Benjamin Jowett, who may have wanted to marry her.[16]

Nightingale continued her travels (now with Charles and Selina Bracebridge) as far as Greece and Egypt. While in Athens, Greece, Nightingale rescued a juvenile little owl from a group of children who were tormenting it, and she named the owl Athena. Nightingale often carried the owl in her pocket, until the pet died (shortly before Nightingale left for Crimea).[17]

Her writings on Egypt, in particular, are testimony to her learning, literary skill, and philosophy of life. Sailing up the Nile as far as Abu Simbel in January 1850, she wrote of the Abu Simbel temples, "Sublime in the highest style of intellectual beauty, intellect without effort, without suffering ... not a feature is correct — but the whole effect is more expressive of spiritual grandeur than anything I could have imagined. It makes the impression upon one that thousands of voices do, uniting in one unanimous simultaneous feeling of enthusiasm or emotion, which is said to overcome the strongest man."[18]

At Thebes, she wrote of being "called to God", while a week later near Cairo she wrote in her diary (as distinct from her far longer letters that her elder sister Parthenope was to print after her return): "God called me in the morning and asked me would I do good for him alone without reputation."[18] Later in 1850, she visited the Lutheran religious community at Kaiserswerth-am-Rhein in Germany, where she observed Pastor Theodor Fliedner and the deaconesses working for the sick and the deprived. She regarded the experience as a turning point in her life and issued her findings anonymously in 1851; The Institution of Kaiserswerth on the Rhine, for the Practical Training of Deaconesses, etc. was her first published work.[19] She also received four months of medical training at the institute, which formed the basis for her later care.

On 22 August 1853, Nightingale took the post of superintendent at the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in Upper Harley Street, London, a position she held until October 1854.[20] Her father had given her an annual income of £500 (roughly £40,000/US$65,000 in present terms), which allowed her to live comfortably and to pursue her career.[21]

Crimean War

Florence Nightingale's most famous contribution came during the Crimean War, which became her central focus when reports got back to Britain about the horrific conditions for the wounded at the military hospital on the Asiatic side of the Bosporus, opposite Constantinople, at Scutari (modern-day Üsküdar in Istanbul). Britain and France entered the war against Russia on the side of the Ottoman Empire. On 21 October 1854, she and the staff of 38 women volunteer nurses including her head nurse Eliza Roberts and her aunt Mai Smith,[22] and 15 Catholic nuns (mobilised by Henry Edward Manning)[23] were sent (under the authorisation of Sidney Herbert) to the Ottoman Empire. On the way, Nightingale was assisted in Paris by her friend Mary Clarke.[24] The volunteer nurses worked about 295 nautical miles (546 km; 339 mi) away from the main British camp across the Black Sea at Balaklava, in the Crimea.

Nightingale arrived at Selimiye Barracks in Scutari early in November 1854. Her team found that poor care for wounded soldiers was being delivered by overworked medical staff in the face of official indifference. Medicines were in short supply, hygiene was being neglected, and mass infections were common, many of them fatal. There was no equipment to process food for the patients:

This frail young woman ... embraced in her solicitude the sick of three armies.

— Lucien Baudens, La guerre de Crimée, les campements, les abris, les ambulances, les hôpitaux, p. 104.[25]

After Nightingale sent a plea to The Times for a government solution to the poor condition of the facilities, the British Government commissioned Isambard Kingdom Brunel to design a prefabricated hospital that could be built in England and shipped to the Dardanelles. The result was Renkioi Hospital, a civilian facility that, under the management of Edmund Alexander Parkes, had a death rate less than one tenth of that of Scutari.[26]

Stephen Paget in the Dictionary of National Biography asserted that Nightingale reduced the death rate from 42% to 2%, either by making improvements in hygiene herself, or by calling for the Sanitary Commission.[27] For example, Nightingale implemented handwashing in the hospital where she worked.[28]

During her first winter at Scutari, 4,077 soldiers died there. Ten times more soldiers died from illnesses such as typhus, typhoid, cholera, and dysentery than from battle wounds. With overcrowding, defective sewers and lack of ventilation, the Sanitary Commission had to be sent out by the British government to Scutari in March 1855, almost six months after Nightingale had arrived. The commission flushed out the sewers and improved ventilation.[29] Death rates were sharply reduced, but she never claimed credit for helping to reduce the death rate.[30][31] Head Nurse Eliza Roberts nursed Nightingale through her critical illness of May 1855.[32]

In 2001 and 2008 the BBC released documentaries that were critical of Nightingale's performance in the Crimean War, as were some follow-up articles published in The Guardian and the Sunday Times. Nightingale scholar Lynn McDonald has dismissed these criticisms as "often preposterous", arguing they are not supported by the primary sources.[12]

Nightingale still believed that the death rates were due to poor nutrition, lack of supplies, stale air, and overworking of the soldiers. After she returned to Britain and began collecting evidence before the Royal Commission on the Health of the Army, she came to believe that most of the soldiers at the hospital were killed by poor living conditions. This experience influenced her later career when she advocated sanitary living conditions as of great importance. Consequently, she reduced peacetime deaths in the army and turned her attention to the sanitary design of hospitals and the introduction of sanitation in working-class homes (see Statistics and Sanitary Reform).[33]

According to some secondary sources, Nightingale had a frosty relationship with her fellow nurse Mary Seacole, who ran a hotel/hospital for officers. Seacole's own memoir, Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands, records only one, friendly, meeting with her, when she asked her for a bed for the night and got it; Seacole was in Scutari en route to the Crimea to join her business partner and start their business. However, Seacole pointed out that when she tried to join Nightingale's group, one of Nightingale's colleagues rebuffed her, and Seacole inferred that racism was at the root of that rebuttal.[34] Nightingale told her brother-in-law, in a private letter, that she was worried about contact between her work and Seacole's business, claiming that while "she was very kind to the men and, what is more, to the Officers – and did some good (she) made many drunk".[35] Nightingale reportedly wrote, "I had the greatest difficulty in repelling Mrs. Seacole's advances, and in preventing association between her and my nurses (absolutely out of the question!) ... Anyone who employs Mrs. Seacole will introduce much kindness – also much drunkenness and improper conduct".[36] On the other hand, Seacole told the French chef Alexis Soyer that "You must know, M Soyer, that Miss Nightingale is very fond of me. When I passed through Scutari, she very kindly gave me board and lodging."[37]

The arrival of two waves of Irish nuns, the Sisters of Mercy, to assist with nursing duties at Scutari met with different responses from Nightingale. Mary Clare Moore headed the first wave and placed herself and her Sisters under the authority of Nightingale. The two were to remain friends for the rest of their lives.[38] The second wave, headed by Mary Francis Bridgeman met with a cooler reception as Bridgeman refused to give up her authority over her Sisters to Nightingale while at the same time not trusting Nightingale, whom she regarded as ambitious.[39][40]

The Lady with the Lamp

During the Crimean War, Nightingale gained the nickname "The Lady with the Lamp" from a phrase in a report in The Times:

She is a "ministering angel" without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow's face softens with gratitude at the sight of her. When all the medical officers have retired for the night and silence and darkness have settled down upon those miles of prostrate sick, she may be observed alone, with a little lamp in her hand, making her solitary rounds.

— William Russell, Cited in Cook, E. T. (1913). The Life of Florence Nightingale. Vol. 1, p. 237.

The phrase was further popularised by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 1857 poem "Santa Filomena":[41]

Lo! in that house of misery

A lady with a lamp I see

Pass through the glimmering gloom,

And flit from room to room.

Nightingale was nicknamed "the lady with the hammer" by the troops after using a hammer to break into locked storage to access medicine to treat the wounded. However, Russell thought the behaviour was unladylike, and invented an alternative, leading to "The Lady with the Lamp".[42][43]

Later career

In the Crimea on 29 November 1855, the Nightingale Fund was established for the training of nurses during a public meeting to recognise Nightingale for her work in the war. There was an outpouring of generous donations. Sidney Herbert served as honorary secretary of the fund and the Duke of Cambridge was chairman. In her 1856 letters she described spas in the Ottoman Empire, detailing the health conditions, physical descriptions, dietary information, and other vital details of patients whom she directed there. She noted that the treatment there was significantly less expensive than in Switzerland.[44]

Nightingale had £45,000 at her disposal from the Nightingale Fund to set up the first nursing school, the Nightingale Training School, at St Thomas' Hospital on 9 July 1860.[45] The first trained Nightingale nurses began work on 16 May 1865 at the Liverpool Workhouse Infirmary. Now called the Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, the school is part of King's College London. In 1866 she said the Royal Buckinghamshire Hospital in Aylesbury near her sister's home Claydon House would be "the most beautiful hospital in England", and in 1868 called it "an excellent model to follow".[46]

Nightingale wrote Notes on Nursing (1859). The book served as the cornerstone of the curriculum at the Nightingale School and other nursing schools, though it was written specifically for the education of those nursing at home. Nightingale wrote, "Every day sanitary knowledge, or the knowledge of nursing, or in other words, of how to put the constitution in such a state as that it will have no disease, or that it can recover from disease, takes a higher place. It is recognised as the knowledge which every one ought to have – distinct from medical knowledge, which only a profession can have".[47]

Notes on Nursing also sold well to the general reading public and is considered a classic introduction to nursing. Nightingale spent the rest of her life promoting and organising the nursing profession. In the introduction to the 1974 edition, Joan Quixley of the Nightingale School of Nursing wrote: "The book was the first of its kind ever to be written. It appeared at a time when the simple rules of health were only beginning to be known, when its topics were of vital importance not only for the well-being and recovery of patients, when hospitals were riddled with infection, when nurses were still mainly regarded as ignorant, uneducated persons. The book has, inevitably, its place in the history of nursing, for it was written by the founder of modern nursing".[48]

As Mark Bostridge has demonstrated, one of Nightingale's signal achievements was the introduction of trained nurses into the workhouse system in Britain from the 1860s onwards.[49] This meant that sick paupers were no longer being cared for by other, able-bodied paupers, but by properly trained nursing staff. In the first half of the 19th century, nurses were usually former servants or widows who found no other job and therefore were forced to earn their living by this work. Charles Dickens caricatured the standard of care in his 1842–1843 published novel Martin Chuzzlewit in the figure of Sarah Gamp as being incompetent, negligent, alcoholic and corrupt. According to Caroline Worthington, director of the Florence Nightingale Museum, "When she [Nightingale] started out there was no such thing as nursing. The Dickens character Sarah Gamp, who was more interested in drinking gin than looking after her patients, was only a mild exaggeration. Hospitals were places of last resort where the floors were laid with straw to soak up the blood. Florence transformed nursing when she got back [from Crimea]. She had access to people in high places and she used it to get things done. Florence was stubborn, opinionated, and forthright but she had to be those things in order to achieve all that she did."[50]

Though Nightingale is sometimes said to have denied the theory of infection for her entire life, a 2008 biography disagrees,[49] saying that she was simply opposed to a precursor of germ theory known as contagionism. This theory held that diseases could only be transmitted by touch. Before the experiments of the mid-1860s by Pasteur and Lister, hardly anyone took germ theory seriously; even afterwards, many medical practitioners were unconvinced. Bostridge points out that in the early 1880s Nightingale wrote an article for a textbook in which she advocated strict precautions designed, she said, to kill germs. Nightingale's work served as an inspiration for nurses in the American Civil War. The Union government approached her for advice in organising field medicine. Her ideas inspired the volunteer body of the United States Sanitary Commission.[52]

Nightingale advocated autonomous nursing leadership, and that her new style of matrons had full control and discipline over their nursing staff.[53] The infamous "Guy's Hospital dispute" in 1879–1880 between matron Margaret Burt and hospital medical staff highlighted how doctors sometimes felt that their authority was being challenged by these new style Nightingale matrons. This was not an isolated episode and other matrons experienced similar issues, such as Eva Luckes.[54]

In the 1870s, Nightingale mentored Linda Richards, "America's first trained nurse", and enabled her to return to the United States with adequate training and knowledge to establish high-quality nursing schools.[55] Richards went on to become a nursing pioneer in the US and Japan.[56]

By 1882, several Nightingale nurses had become matrons at several leading hospitals, including, in London (St Mary's Hospital, Westminster Hospital, St Marylebone Workhouse Infirmary and the Hospital for Incurables at Putney) and throughout Britain (Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley; Edinburgh Royal Infirmary; Cumberland Infirmary and Liverpool Royal Infirmary), as well as at Sydney Hospital in New South Wales, Australia.[57]

In 1883, Nightingale became the first recipient of the Royal Red Cross. In 1904, she was appointed a Lady of Grace of the Order of St John (LGStJ).[59]

In 1907, she became the first woman to be awarded the Order of Merit.[60] In the following year she was given the Honorary Freedom of the City of London.

Her birthday is now celebrated as International May 12th Awareness Day.[61]

From 1857 onwards, Nightingale was intermittently bedridden and suffered from depression. A recent biography cites brucellosis and associated spondylitis as the cause.[62] Most authorities today accept that Nightingale suffered from a particularly extreme form of brucellosis, the effects of which only began to lift in the early 1880s. Despite her symptoms, she remained phenomenally productive in social reform. During her bedridden years, she also did pioneering work in the field of hospital planning, and her work propagated quickly across Britain and the world. Nightingale's output slowed down considerably in her last decade. She wrote very little during that period due to blindness and declining mental abilities, though she still retained an interest in current affairs.[12]

Relationships

Although much of Nightingale's work improved the lot of women everywhere, Nightingale believed that women craved sympathy and were not as capable as men.[a] She criticised early women's rights activists for decrying an alleged lack of careers for women at the same time that lucrative medical positions, under the supervision of Nightingale and others, went perpetually unfilled.[b] She preferred the friendship of powerful men, insisting they had done more than women to help her attain her goals, writing: "I have never found one woman who has altered her life by one iota for me or my opinions."[65][66] She often referred to herself as, for example, "a man of action" and "a man of business".[67]

However, she did have several important and long-lasting friendships with women. Later in life, she kept up a prolonged correspondence with Irish nun Mary Clare Moore, with whom she had worked in Crimea.[68] Her most beloved confidante was Mary Clarke, an Englishwoman she met in Paris in 1837 and kept in touch with throughout her life.[69]

Some scholars of Nightingale's life believe that she remained chaste for her entire life, perhaps because she felt a religious calling to her career.[70]

Death

Florence Nightingale died peacefully in her sleep in her room at 10 South Street, Mayfair, London, on 13 August 1910, at the age of 90.[71][c] The offer of burial in Westminster Abbey was declined by her relatives and she is buried in the churchyard of St Margaret's Church in East Wellow, Hampshire, near Embley Park with a memorial with just her initials and dates of birth and death.[73][74] She left a large body of work, including several hundred notes that were previously unpublished.[75] A memorial monument to Nightingale was created in Carrara marble by Francis William Sargant in 1913 and placed in the cloister of the Basilica of Santa Croce, in Florence, Italy.[76]

Contributions

Statistics and sanitary reform

Florence Nightingale exhibited a gift for mathematics from an early age and excelled in the subject under the tutelage of her father.[d] Later, Nightingale became a pioneer in the visual presentation of information and statistical graphics.[78] She used methods such as the pie chart, which had first been developed by William Playfair in 1801.[79] While common now, it was at the time a relatively novel method of presenting data.[80]

Indeed, Nightingale is described as "a true pioneer in the graphical representation of statistics" and is especially well known for her usage of a polar area diagram,[80]: 107 or occasionally the Nightingale rose diagram, equivalent to a modern circular histogram, to illustrate seasonal sources of patient mortality in the military field hospital she managed. While frequently credited as the creator of the polar area diagram, it is known to have been used by André-Michel Guerry in 1829[81] and Léon Louis Lalanne by 1830.[82] Nightingale called a compilation of such diagrams a "coxcomb", but later that term would frequently be used for the individual diagrams.[83] She made extensive use of coxcombs to present reports on the nature and magnitude of the conditions of medical care in the Crimean War to Members of Parliament and civil servants who would have been unlikely to read or understand traditional statistical reports. In 1859, Nightingale was elected the first female member of the Royal Statistical Society.[84] In 1874 she became an honorary member of the American Statistical Association.[85]

Her attention turned to the health of the British Army in India and she demonstrated that bad drainage, contaminated water, overcrowding, and poor ventilation were causing the high death rate.[86] Following the report The Royal Commission on India (1858–1863), which included drawings done by her cousin, artist Hilary Bonham Carter, with whom Nightingale had lived,[e] Nightingale concluded that the health of the army and the people of India had to go hand in hand and so campaigned to improve the sanitary conditions of the country as a whole.[7]

Nightingale made a comprehensive statistical study of sanitation in Indian rural life and was the leading figure in the introduction of improved medical care and public health service in India. In 1858 and 1859, she successfully lobbied for the establishment of a Royal Commission into the Indian situation. Two years later, she provided a report to the commission, which completed its own study in 1863. "After 10 years of sanitary reform, in 1873, Nightingale reported that mortality among the soldiers in India had declined from 69 to 18 per 1,000".[80]: 107

The Royal Sanitary Commission of 1868–1869 presented Nightingale with an opportunity to press for compulsory sanitation in private houses. She lobbied the minister responsible, James Stansfeld, to strengthen the proposed Public Health Bill to require owners of existing properties to pay for connection to mains drainage.[88] The strengthened legislation was enacted in the Public Health Acts of 1874 and 1875. At the same time, she combined with the retired sanitary reformer Edwin Chadwick to persuade Stansfeld to devolve powers to enforce the law to Local Authorities, eliminating central control by medical technocrats.[89] Her Crimean War statistics had convinced her that non-medical approaches were more effective given the state of knowledge at the time. Historians now believe that both drainage and devolved enforcement played a crucial role in increasing average national life expectancy by 20 years between 1871 and the mid-1930s during which time medical science made no impact on the most fatal epidemic diseases.[30][31][90]

Literature and the women's movement

Historian of science I. Bernard Cohen argues:

Nightingale's achievements are all the more impressive when they are considered against the background of social restraints on women in Victorian England. Her father, William Edward Nightingale, was an extremely wealthy landowner, and the family moved in the highest circles of English society. In those days, women of Nightingale's class did not attend universities and did not pursue professional careers; their purpose in life was to marry and bear children. Nightingale was fortunate. Her father believed women should be educated, and he personally taught her Italian, Latin, Greek, philosophy, history, and – most unusual of all for women of the time – writing and mathematics.[80]: 98

Lytton Strachey was famous for his book debunking 19th-century heroes, Eminent Victorians (1918). Nightingale gets a full chapter, but instead of debunking her, Strachey praised her in a way that raised her national reputation and made her an icon for English feminists of the 1920s and 1930s.[91]

While better known for her contributions in the nursing and mathematical fields, Nightingale is also an important link in the study of English feminism. She wrote some 200 books, pamphlets and articles throughout her life.[50] During 1850 and 1852, she was struggling with her self-definition and the expectations of an upper-class marriage from her family. As she sorted out her thoughts, she wrote Suggestions for Thought to Searchers after Religious Truth. This was an 829-page, three-volume work, which Nightingale had printed privately in 1860, but which until recently was never published in its entirety.[92] An effort to correct this was made with a 2008 publication by Wilfrid Laurier University, as volume 11[93] of a 16 volume project, the Collected Works of Florence Nightingale.[94] The best known of these essays, called "Cassandra", was previously published by Ray Strachey in 1928. Strachey included it in The Cause, a history of the women's movement. Apparently, the writing served its original purpose of sorting out thoughts; Nightingale left soon after to train at the Institute for deaconesses at Kaiserswerth.

"Cassandra" protests the over-feminisation of women into near helplessness, such as Nightingale saw in her mother's and older sister's lethargic lifestyle, despite their education. She rejected their life of thoughtless comfort for the world of social service. The work also reflects her fear of her ideas being ineffective, as were Cassandra's. Cassandra was a princess of Troy who served as a priestess in the temple of Apollo during the Trojan War. The god gave her the gift of prophecy; when she refused his advances, he cursed her so that her prophetic warnings would go unheeded. Elaine Showalter called Nightingale's writing "a major text of English feminism, a link between Wollstonecraft and Woolf".[95] Nightingale was initially reluctant to join the Women's Suffrage Society when asked by John Stuart Mill, but through Josephine Butler was convinced 'that women's enfranchisement is absolutely essential to a nation if moral and social progress is to be made'.[96]

In 1972, the poet Eleanor Ross Taylor wrote "Welcome Eumenides", a poem written in Nightingale's voice and quoting frequently from Nightingale's writings.[97] Adrienne Rich wrote that "Eleanor Taylor has brought together the waste of women in society and the waste of men in wars and twisted them inseparably."[98]

Theology

Despite being named as a Unitarian in several older sources, Nightingale's own rare references to conventional Unitarianism are mildly negative. She remained in the Church of England throughout her life, albeit with unorthodox views. Influenced from an early age by the Wesleyan tradition,[f] Nightingale felt that genuine religion should manifest in active care and love for others.[g] She wrote a work of theology: Suggestions for Thought, her own theodicy, which develops her heterodox ideas. Nightingale questioned the goodness of a God who would condemn souls to hell and was a believer in universal reconciliation – the concept that even those who die without being saved will eventually make it to heaven.[h] She would sometimes comfort those in her care with this view. For example, a dying young prostitute being tended by Nightingale was concerned she was going to hell and said to her "Pray God, that you may never be in the despair I am in at this time". The nurse replied "Oh, my girl, are you not now more merciful than the God you think you are going to? Yet the real God is far more merciful than any human creature ever was or can ever imagine."[11][66][i][j]

Despite her intense personal devotion to Christ, Nightingale believed for much of her life that the pagan and eastern religions had also contained genuine revelation. She was a strong opponent of discrimination both against Christians of different denominations and against those of non-Christian religions. Nightingale believed religion helped provide people with the fortitude for arduous good work and would ensure the nurses in her care attended religious services. However, she was often critical of organised religion. She disliked the role the 19th century Church of England would sometimes play in worsening the oppression of the poor. Nightingale argued that secular hospitals usually provided better care than their religious counterparts. While she held that the ideal health professional should be inspired by a religious as well as professional motive, she said that in practice many religiously motivated health workers were concerned chiefly in securing their own salvation and that this motivation was inferior to the professional desire to deliver the best possible care.[11][66]

Legacy

Nursing

Nightingale's lasting contribution has been her role in founding the modern nursing profession.[102] She set an example of compassion, commitment to patient care and diligent and thoughtful hospital administration. The first official nurses' training programme, her Nightingale School for Nurses, opened in 1860 and is now called the Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery at King's College London.[103]

She belongs to that select band of historical characters who are instantly recognisable: the Lady with the Lamp, ministering to the wounded and dying.

In 1912, the International Committee of the Red Cross instituted the Florence Nightingale Medal, which is awarded every two years to nurses or nursing aides for outstanding service.[104] It is the highest international distinction a nurse can achieve and is awarded to nurses or nursing aides for "exceptional courage and devotion to the wounded, sick or disabled or to civilian victims of a conflict or disaster" or "exemplary services or a creative and pioneering spirit in the areas of public health or nursing education".[105] Since 1965, International Nurses Day has been celebrated on her birthday (12 May) each year.[106] The President of India honours nursing professionals with the "National Florence Nightingale Award" every year on International Nurses Day.[107] The award, established in 1973, is given in recognition of meritorious services of nursing professionals characterised by devotion, sincerity, dedication and compassion.[107]

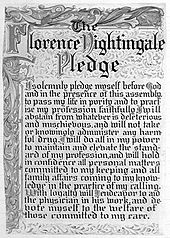

The Nightingale Pledge is a modified version of the Hippocratic Oath which nurses in the United States recite at their pinning ceremony at the end of training. Created in 1893 and named after Nightingale as the founder of modern nursing, the pledge is a statement of the ethics and principles of the nursing profession.[108]

The Florence Nightingale Declaration Campaign,[109] established by nursing leaders throughout the world through the Nightingale Initiative for Global Health (NIGH), aims to build a global grassroots movement to achieve two United Nations Resolutions for adoption by the UN General Assembly of 2008. They will declare: The International Year of the Nurse–2010 (the centenary of Nightingale's death); The UN Decade for a Healthy World – 2011 to 2020 (the bicentenary of Nightingale's birth). NIGH also works to rekindle awareness about the important issues highlighted by Florence Nightingale, such as preventive medicine and holistic health. As of 2016, the Florence Nightingale Declaration has been signed by over 25,000 signatories from 106 countries.[110]

During the Vietnam War, Nightingale inspired many US Army nurses, sparking a renewal of interest in her life and work. Her admirers include Country Joe of Country Joe and the Fish, who has assembled an extensive website in her honour.[111] The Agostino Gemelli Medical School[112] in Rome, the first university-based hospital in Italy and one of its most respected medical centres, honoured Nightingale's contribution to the nursing profession by giving the name "Bedside Florence" to a wireless computer system it developed to assist nursing.[113]

Hospitals

Four hospitals in Istanbul are named after Nightingale: Florence Nightingale Hospital in Şişli (the biggest private hospital in Turkey), Metropolitan Florence Nightingale Hospital in Gayrettepe, European Florence Nightingale Hospital in Mecidiyeköy, and Kızıltoprak Florence Nightingale Hospital in Kadıköy, all belonging to the Turkish Cardiology Foundation.[114]

In 2011, an appeal was made for the former Derbyshire Royal Infirmary hospital in Derby, England to be named after Nightingale. It was suggested the name could be either Nightingale Community Hospital or Florence Nightingale Community Hospital. The area where the hospital is situated is sometimes referred to as the "Nightingale Quarter".[115]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a number of temporary NHS Nightingale Hospitals were set up in readiness for an expected rise in the number of patients needing critical care. The first was housed in the ExCeL London[116] and several others followed across England.[117] Celebrations to mark her bicentenary in 2020, were disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic and Nightingale's contribution to scientific and statistical analysis of infectious disease and nursing practice may have led to the new temporary hospitals being in her name, in Scotland named the NHS Louisa Jordan after a nurse who followed in Nightingale's footsteps in battlefield nursing in World War One.[118]

Museums and monuments

A statue of Florence Nightingale by the 20th-century war memorialist Arthur George Walker stands in Waterloo Place, Westminster, London, just off The Mall. There are three statues of Nightingale in Derby – one outside the Derbyshire Royal Infirmary (DRI), one in St Peter's Street, and one above the Nightingale-Macmillan Continuing Care Unit opposite the Derbyshire Royal Infirmary. A pub named after her stands close to the DRI.[119] The Nightingale-Macmillan continuing care unit is now at the Royal Derby Hospital, formerly known as The City Hospital, Derby.[120]

A stained glass window was commissioned for inclusion in the DRI chapel in the late 1950s. When the chapel was demolished the window was removed and installed in the replacement chapel. At the closure of the DRI, the window was again removed and stored. In October 2010, £6,000 was raised to reposition the window in St Peter's Church, Derby. The work features nine panels, of the original ten, depicting scenes of hospital life, Derby townscapes, and Nightingale herself. Some of the work was damaged and the tenth panel was dismantled for the glass to be used in the repair of the remaining panels. All the figures, who are said to be modelled on prominent Derby town figures of the early sixties, surround and praise a central pane of the triumphant Christ. A nurse who posed for the top right panel in 1959 attended the rededication service in October 2010.[121]

The Florence Nightingale Museum at St Thomas' Hospital in London reopened in May 2010 in time for the centenary of Nightingale's death.[50] Another museum devoted to her is at her sister's family home, Claydon House, now a property of the National Trust.[122][123]

Upon the centenary of Nightingale's death in 2010, and to commemorate her connection with Malvern, the Malvern Museum held a Florence Nightingale exhibit[124] with a school poster competition to promote some events.[125]

In Istanbul, the northernmost tower of the Selimiye Barracks building is now the Florence Nightingale Museum.[126] and in several of its rooms, relics and reproductions related to Florence Nightingale and her nurses are on exhibition.[127]

When Nightingale moved on to the Crimea itself in May 1855, she often travelled on horseback to make hospital inspections. She later transferred to a mule cart and was reported to have escaped serious injury when the cart was toppled in an accident. Following this, she used a solid Russian-built black carriage, with a waterproof hood and curtains. The carriage was returned to England by Alexis Soyer after the war and subsequently given to the Nightingale training school. The carriage was damaged when the hospital was bombed during the Second World War. It was restored and transferred to Claydon House and is now displayed at the Army Medical Services Museum in Mytchett, Surrey, near Aldershot.[128]

A bronze plaque, attached to the plinth of the Crimean Memorial in the Haydarpaşa Cemetery, Istanbul, Turkey and unveiled on Empire Day, 1954, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of her nursing service in that region, bears the inscription: "To Florence Nightingale, whose work near this Cemetery a century ago relieved much human suffering and laid the foundations for the nursing profession."[129] Other monuments of Nightingale include a statue at Chiba University in Japan, a bust at Tarlac State University in the Philippines, and a bust at Gun Hill Park in Aldershot in the UK. Other nursing schools around the world are named after Nightingale, such as in Anápolis in Brazil.[130]

Audio

Florence Nightingale's voice was saved for posterity in a phonograph recording from 1890 preserved in the British Library Sound Archive. The recording, made in aid of the Light Brigade Relief Fund and available to hear online, says:

When I am no longer even a memory, just a name, I hope my voice may perpetuate the great work of my life. God bless my dear old comrades of Balaclava and bring them safe to shore. Florence Nightingale.[131]

Theatre

The first theatrical representation of Nightingale was Reginald Berkeley's The Lady with the Lamp, premiering in London in 1929 with Edith Evans in the title role. It did not portray her as an entirely sympathetic character and draws much characterisation from Lytton Strachey's biography of her in Eminent Victorians.[132] It was adapted as a film of the same name in 1951. In 2009, a stage musical play representation of Nightingale entitled The Voyage of the Lass was produced by the Association of Nursing Service Administrators of the Philippines.

Film

In 1912, a biographical silent film titled The Victoria Cross, starring Julia Swayne Gordon as Nightingale, was released, followed in 1915 by another silent film, Florence Nightingale, featuring Elisabeth Risdon. In 1936, Kay Francis played Nightingale in the film titled The White Angel. In 1951, The Lady with a Lamp starred Anna Neagle.[133] In 1993, Nest Entertainment released an animated film Florence Nightingale, describing her service as a nurse in the Crimean War.[134]

Television

Portrayals of Nightingale on television, in documentary as in fiction, vary – the BBC's 2008 Florence Nightingale, featuring Laura Fraser,[135] emphasised her independence and feeling of religious calling, but in Channel 4's 2006 Mary Seacole: The Real Angel of the Crimea, she is portrayed as narrow-minded and opposed to Seacole's efforts.[136]

Other portrayals include:

- Laura Morgan in Victoria episode #3.4 "Foreign Bodies" (2018)[137]

- Kate Isitt in the Magic Grandad episode "Famous People: Florence Nightingale" (1994)[138]

- Jaclyn Smith in the TV biopic Florence Nightingale (1985)[139]

- Emma Thompson in the ITV sketch comedy series Alfresco episode #1.2 (1983)[140]

- Jayne Meadows in PBS series Meeting of Minds (1978)[141]

- Janet Suzman in the British theatre-style biopic Miss Nightingale (1974)[142]

- Julie Harris in Hallmark Hall of Fame episode #14.4 "The Holy Terror" (1965)[143]

- Sarah Churchill in Hallmark Hall of Fame episode #1.6 "Florence Nightingale" (1952)[144]

Banknotes

Florence Nightingale's image appeared on the reverse of £10 Series D banknotes issued by the Bank of England from 1975 until 1994. As well as a standing portrait, she was depicted on the notes in a field hospital, holding her lamp.[146] Nightingale's note was in circulation alongside the images of Isaac Newton, William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Michael Faraday, Sir Christopher Wren, the Duke of Wellington and George Stephenson, and prior to 2002, other than the female monarchs, she was the only woman whose image had ever adorned British paper currency.[7]

The centenary of her death in 2010 was also commemorated with a special £2 coin showing her taking a patient's pulse.[145]

Photographs

Nightingale had a principled objection to having photographs taken or her portrait painted. An extremely rare photograph of her, taken at Embley on a visit to her family home in May 1858, was discovered in 2006 and is now at the Florence Nightingale Museum in London. A black-and-white photograph taken in about 1907 by Lizzie Caswall Smith at Nightingale's London home in South Street, Mayfair, was auctioned on 19 November 2008 by Dreweatts auction house in Newbury, Berkshire, England, for £5,500.[147]

Biographies

The first biography of Nightingale was published in England in 1855. In 1911, Edward Tyas Cook was authorised by Nightingale's executors to write the official life, published in two volumes in 1913. Nightingale was also the subject of one of Lytton Strachey's four mercilessly provocative biographical essays, Eminent Victorians. Strachey regarded Nightingale as an intense, driven woman who was both personally intolerable and admirable in her achievements.[149]

Cecil Woodham-Smith, like Strachey, relied heavily on Cook's Life in her 1950 biography, though she did have access to new family material preserved at Claydon. In 2008, Mark Bostridge published a major new life of Nightingale, almost exclusively based on unpublished material from the Verney Collections at Claydon and from archival documents from about 200 archives around the world, some of which had been published by Lynn McDonald in her projected sixteen-volume edition of the Collected Works of Florence Nightingale (2001 to date).[7]

Other

In 2002, Nightingale was ranked number 52 in the BBC's list of the 100 Greatest Britons following a UK-wide vote. In 2006, the Japanese public ranked Nightingale number 17 in The Top 100 Historical Persons in Japan.[150]

Several churches in the Anglican Communion commemorate Nightingale with a feast day on their liturgical calendars.[151] The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America commemorates her as a Renewer of Society with Clara Maass on 13 August.[152] Florence Li Tim-Oi, the first woman ordained priest in the Anglican Communion, in 1944, took Florence as her baptismal name after Florence Nightingale.[153]

Washington National Cathedral celebrates Nightingale's accomplishments with a double-lancet stained glass window featuring six scenes from her life, designed by artist Joseph G. Reynolds and installed in 1983.[154]

The US Navy ship the USS Florence Nightingale (AP-70) was commissioned in 1942. Beginning in 1968, the US Air Force operated a fleet of 20 C-9A "Nightingale" aeromedical evacuation aircraft, based on the McDonnell Douglas DC-9 platform.[155] The last of these planes was retired from service in 2005.[156]

In 1981, the asteroid 3122 Florence was named after her.[157] A Dutch KLM McDonnell-Douglas MD-11 (registration PH-KCD) was also named in her honour; it served the airline for 20 years, from 1994 to 2014.[158][159] Nightingale has appeared on international postage stamps, including, the UK, Alderney, Australia, Belgium, Dominica, Hungary (showing the Florence Nightingale medal awarded by the International Red Cross), and Germany.[160]

Florence Nightingale is remembered in the Church of England with a commemoration on 13 August.[161] Celebrations to mark her bicentenary in 2020, were disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic, but the NHS Nightingale hospitals were named after her.[118] Nightingale Road (Chinese: 南丁格爾路) in Hong Kong, between the Queen Elizabeth Hospital and the nursing school, was officially named by the Lands Department after Florence Nightingale in 2008.[162]

Gallery

-

A tinted lithograph by William Simpson illustrating evacuation of the sick and injured from Balaklava

-

Picture of Nightingale in The Illustrated London News, 24 February 1855

-

A ward of the hospital at Scutari where Nightingale worked, from an 1856 lithograph by William Simpson

-

Nightingale's moccasins that she wore in the Crimean War (the other items are not hers)

-

Florence Nightingale exhibit at Malvern Museum, England, 2010

-

Nightingale's medals displayed in the National Army Museum

-

Memorial to Nightingale, Church of Santa Croce, Florence, Italy

Works

- Nightingale, Florence (1979). Cassandra. The Feminist Press. ISBN 978-0-912670-55-3. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- "Notes on Nursing: What Nursing Is, What Nursing is Not". Philadelphia, London, Montreal: J.B. Lippincott Co. 1946 Reprint. Harrison & Sons. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

First published London, 1859

- Nightingale, Florence (2001). McDonald, Lynn (ed.). Florence Nightingale's Spiritual Journey: Biblical Annotations, Sermons and Journal Notes. Collected Works of Florence Nightingale. Vol. 2. Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-366-2. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- Nightingale, Florence (2002). McDonald, Lynn (ed.). Florence Nightingale's Theology: Essays, Letters and Journal Notes. Collected Works of Florence Nightingale. Vol. 3. Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-371-6. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- Nightingale, Florence (2003). Vallee, Gerard (ed.). Mysticism and Eastern Religions. Collected Works of Florence Nightingale. Vol. 4. Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-413-3. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- Nightingale, Florence (2008). McDonald, Lynn (ed.). Suggestions for Thought. Collected Works of Florence Nightingale. Vol. 11. Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-465-2. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2010. Privately printed by Nightingale in 1860.

- Notes on Nursing for the Labouring Classes. London: Harrison. 1861. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- The Family, a critical essay in Fraser's Magazine (1870)

- "Introductory Notes on Lying-In Institutions". Nature. 5 (106). London: 22–23. 1871. Bibcode:1871Natur...5...22.. doi:10.1038/005022a0. S2CID 3985727. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- Una and the Lion. Cambridge: Riverside Press. 1871. Retrieved 6 July 2010. Note: First few pages missing. Title page is present.

- Una and Her Paupers, Memorials of Agnes Elizabeth Jones, by her sister. with an introduction by Florence Nightingale. New York: George Routledge and Sons. 1872. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link). See also 2005 publication by Diggory Press, ISBN 978-1-905363-22-3 - Nightingale, Florence (1987). Letters from Egypt: A Journey on the Nile 1849–1850. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 1-55584-204-6.

- Nightingale, Florence (1867). . London: Macmillan and Co.

See also

Explanatory footnotes

- ^ In an 1861 letter Nightingale wrote, "Women have no sympathy. ... Women crave for being loved, not for loving. They scream out at you for sympathy all day long, they are incapable of giving any in return, for they cannot remember your affairs long enough to do so. ... They cannot state a fact accurately to another, nor can that other attend to it accurately enough for it to become information."[63]

- ^ In the same 1861 letter she wrote, "It makes me mad, the Women's Rights talk about 'the want of a field' for them – when I would gladly give £500 a year for a Woman secretary. And two English Lady superintendents have told me the same thing. And we can't get one ..."[64]

- ^ Florence Nightingale, the famous nurse of the Crimean war and the only woman who ever received the Order of Merit, died yesterday afternoon at her London home. Although she had been an invalid for a long time, rarely leaving her room, where she passed the time in a half-recumbent position and was under the constant care of a physician, her death was somewhat unexpected. A week ago she was quite sick, but then improved and on Friday was cheerful. During that night alarming symptoms developed and she gradually sank until 2 o'clock Saturday afternoon, when the end came. — New York Times (15 Aug 1910)[72]

- ^ There were rumours that she was tutored by an eminent mathematician who was a friend of the family. Mark Bostridge says, "There appears to be no documentary evidence to connect Florence with J. J. Sylvester."[77]

- ^ [many letters were written by Nightingale to her cousin Hilary Bonham-Carter] ... Royal Commission on India (1858–1863) ... feeling that her cousin was neglecting her art, [Nightingale] made Hilary Bonham Carter leave ... the Indian embroidery belonged to dear Hilary ...[87]

- ^ Her parents took their daughters to both Church of England and Methodist churches.[citation needed]

- ^ Nightingale's rare references to Unitarianism are mildly negative, and while her religious views were heterodox, she remained in the Church of England throughout her life. Her biblical annotations, private journal notes, and translations of the mystics give quite a different impression of her beliefs, and these do have a bearing on her work with nurses, and not only at Edinburgh, but neither [Cecil(ia) Woodham-]Smith nor [her] followers consulted their sources."[99]

- ^ While this has changed by the 21st century, universal reconciliation was very far from being mainstream in the Church of England at the time.

- ^ "Certainly the worst man would hardly torture his enemy, if he could, forever. Unless God has a scheme that every man is to be saved forever, it is hard to say in what He is not worse than man. For all good men would save others if they could."[100]

- ^ Although not formally a Universalist by church membership, she had come of a Universalist family, was sympathetic to the tenets of the denomination, and has always been claimed by it.[101]

Citations

- ^ "Florence Nightingale". King's College London. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ "Florence Nightingale 2nd rendition, 1890 – greetings to the dear old comrades of Balaclava". Internet Archive. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Buhnemann, Kristin (17 February 2020). "Florence Nightingale's Voice, 1890". florence-nightingale.co.uk. Florence Nightingale Museum London. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ Strachey, Lytton (1918). Eminent Victorians. London: Chatto and Windus. p. 123.

- ^ Swenson, Kristine (2005). Medical Women and Victorian Fiction. University of Missouri Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-8262-6431-2.

- ^ Ralby, Aaron (2013). "The Crimean War 1853–1856". Atlas of Military History. Parragon. pp. 281. ISBN 978-1-4723-0963-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bostridge, Mark (17 February 2011). "Florence Nightingale: the Lady with the Lamp". BBC. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ Petroni, A (1969). "The first nursing school in the world – St. Thomas Hospital School in London". Munca Sanit. 17 (8): 449–454. PMID 5195090.

- ^ Shiller, Joy (1 December 2007). "The true Florence: Exploring the Italian birthplace of Florence Nightingale". Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ "Florence Nightingale" Archived 3 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine. JMVH.org. Retrieved 17 June 2020

- ^ a b c Nightingale, Florence (2003). "Introduction, passim". In Vallee, Gerard (ed.). Florence Nightingale on Mysticism and Eastern Religions. Collected Works of Florence Nightingale. Vol. 4. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-413-3.

- ^ a b c d Nightingale, Florence (2010). "An introduction to volume 14". In McDonald, Lynn (ed.). Florence Nightingale: The Crimean War. Collected Works of Florence Nightingale. Vol. 14. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-469-0.

- ^ "Pedigree of Shore of Sheffield, Meersbrook, Norton and Tapton". Rotherham Web. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ Cromwell, Judith Lissauer (2013). Florence Nightingale, feminist. Jefferson, NC [u.a.]: McFarland et Company. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7864-7092-1.

- ^ a b Small, Hugh (2017). Florence Nightingale and Her Real Legacy. London: Robinson. pp. 1–19.

- ^ Bostridge, Mark (2008). Florence Nightingale. pg. 8. London

- ^ "Life and death of Florence Nightingale's beloved pet". Trinity College, Cambridge. 28 December 2016. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ a b Chaney, Edward (2006). "Egypt in England and America: The Cultural Memorials of Religion, Royalty and Revolution". In Ascari, M.; Corrado, A. (eds.). Sites of Exchange European Crossroads and Faultlines. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi. pp. 39–74.

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ "History of Harley Street". Harley Street Guide. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2009. (commercial website)

- ^ "Shining a light on 'The Lady with the Lamp'". Unison magazine. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ Gill, Christopher J.; Gill, Gillian C. (June 2005). "Nightingale in Scutari: Her Legacy Reexamined". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 40 (12): 1799–1805. doi:10.1086/430380. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 15909269.

- ^ Mary Jo Weaver (1985). New Catholic Women: a Contemporary Challenge to Traditional Religious Authority. San Francisco: Harper and Row. p. 31. citing Hartley, Olga (1935). Women and the Catholic Church. London: Buns, Oates & Washbourne. pp. 222–223.

- ^ Patrick Waddington (January 2007) [first published 2004]. "Mohl, Mary Elizabeth (1793–1883)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. Accessed 7 February 2015.

- ^ Baudens, Lucien (1858). La Guerre de Crimée. Les campements, les bris, iles ambulances, les hôpitaux, etc (in French). Paris, France: Michel Lévy frères. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Report on Medical Care". Archived 2 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. United Kingdom: The National Archives (WO 33/1 ff.119, 124, 146–7). 23 February 1855.

- ^ Lee, Sidney, ed. (1912). . Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). Vol. 3. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ "History". The Global Handwashing Partnership. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Nightingale, Florence (1999). Florence Nightingale: Measuring Hospital Care Outcomes. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. ISBN 978-0-86688-559-1.

- ^ a b Small, Hugh (1998). Florence Nightingale, Avenging Angel. Constable. p. 861. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ a b Nightingale, Florence (1914). Florence Nightingale to Her Nurses: A Selection From Miss Nightingale's Addresses to Probationers and Nurses of the Nightingale School at St Thomas's Hospital. London: Macmillan.

- ^ McDonald, Lynn, ed. Florence Nightingale: The Crimean War in Collected Works. vol. xiv, 2010, pp. 65, 384 & 1038

- ^ Small, Hugh (2017). Florence Nightingale and Her Real Legacy. London: Robinson. pp. 171–179.

- ^ Mary Seacole, Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands, Chapter VIII (London: James Blackwood, 1857), pp. 73–81

- ^ letter 4 August 1870, Wellcome Ms 9004/59).

- ^ Chang, Tan-Feng (Fall 2017). "Creolizing the White Woman's Burden: Mary Seacole Playing "Mother" at the Colonial Crossroads Between Panama and Crimea". College Literature. 44 (4). Johns Hopkins University Press: 527–557. doi:10.1353/lit.2017.0033. ISSN 1542-4286. JSTOR 48553646.

- ^ Soyer, p. 434.

- ^ "Irish Nurses at the Crimean War". Careful Nursing: Philosophy & Professional Practice Model. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Bridgeman, M. F. (1854–1856). "An Account of the Mission of the Sisters of Mercy in the Military Hospitals of the East, Beginning December 1854 and Ending May 1856". Unpublished manuscript, Archives of the Sisters of Mercy, Dublin, p. 18

- ^ Carol Helmstadter (2019). Beyond Nightingale: Nursing on the Crimean War Battlefields. Archived 31 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Manchester University Press.

- ^ Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth (November 1857). "Santa Filomena". The Atlantic Monthly. pp. 22–23. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Miles, Rosalind (23 April 2020). "Rebel Women, Florence Nightingale". Hachette UK. Little, Brown Book Group. Retrieved 19 March 2024 – via Virago Press.

- ^ Martini, Mariano; Lippi, Donatella (15 September 2021). "SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) and the Teaching of Ignaz Semmelweis and Florence Nightingale: a Lesson of Public Health from History, after the "Introduction of Handwashing" (1847)". Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene. 62 (3): 621–624. doi:10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2021.62.3.2161. PMC 8639136. PMID 34909488. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ The Role of Anesthesiology in Global Health: A Comprehensive Guide. Springer. 2014. p. 9.

- ^ Karimi, H.; Masoudi Alavi, N. (2015). "Florence Nightingale: The Mother of Nursing". National Institutes of Health. Vol. 4, no. 2. pp. e29475. PMC 4557413. PMID 26339672.

- ^ Florence Nightingale and Hospital Reform: Collected Works of Florence Nightingale, volume 16. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. 2012. p. 639.

- ^ Nightingale, Florence (1974) [1859]. "Preface". Notes on Nursing: What it is and what it is not. Glasgow and London: Blackie & Son. ISBN 978-0-216-89974-2.

- ^ Nightingale, Florence (1974) [1859]. "Introduction by Joan Quixley". Notes on Nursing: What it is and what it is not. Blackie & Son. ISBN 978-0-216-89974-2.

- ^ a b Mark Bostridge (2008). Florence Nightingale, the Woman and her Legend. Viking.

- ^ a b c "Florence Nightingale: the medical superstar". Daily Express. 12 May 2016. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "2013.0503 | Collections Online". collections.thackraymuseum.co.uk. Retrieved 30 May 2024.

- ^ "The Sanitary Commission—The Red Cross". Cambridge University Press. JSTOR. 1910. JSTOR 2186240.

- ^ Vicinus, Martha (1985). Independent Women, Work and Community for Single Women, 1850–1920. London: The University of Chicago Press. p. 109.

- ^ Rogers, Sarah (2022). "'A Maker of Matrons'? A study of Eva Lückes's influence on a generation of nurse leaders: 1880–1919"[permanent dead link] (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Huddersfield, April 2022).

- ^ Role Development for Doctoral Advanced Nursing Practice. Springer Publishing Company. 15 December 2010. p. 325.

- ^ Linda Richards (1915) Reminiscences of Linda Richards, Whitcomb & Barrows, Boston OCLC 1350705

- ^ "Bicentenary of a hospital built from a rum deal". Sydney Morning Herald. 26 October 2017. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "534004 | Collections Online". collections.thackraymuseum.co.uk. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "No. 27677". The London Gazette. 17 May 1904. p. 3185.

- ^ "No. 28084". The London Gazette. 29 November 1907. p. 8331.

- ^ "May 12th International Awareness Day". Archived from the original on 18 July 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ Bostridge (2008)

- ^ published in The Life of Florence Nightingale vol. 2 of 2 by Edward Tyas Cook, pp. 14–17 at Project Gutenberg

- ^ available at Project Gutenberg

- ^ The same 1861 letter published in The Life of Florence Nightingale vol. 2 of 2 by Edward Tyas Cook, pp. 14–17 at Project Gutenberg

- ^ a b c Nightingale, Florence (2005). McDonald, Lynn (ed.). Florence Nightingale on Women, Medicine, Midwifery and Prostitution. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 7, 48–49, 414. ISBN 978-0-88920-466-9.

- ^ Stark, Myra. "Florence Nightingale's Cassandra". The Feminist Press, 1979, p. 17.

- ^ "Institute of Our Lady of Mercy, Great Britain". Ourladyofmercy.org.uk. 8 December 2009. Archived from the original on 21 February 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Cannadine, David. "Ever Yours, Florence Nightingale: Selected Letters." The New Republic. 203.7 (13 August 1990): 38–42.

- ^ Dossey, Barbara Montgomery. Florence Nightingale: Mystic, Visionary, Reformer. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

- ^ Plaque #6 on Open Plaques

- ^ "Miss Nightingale Dies, Aged Ninety". The New York Times. 15 August 1910. Archived from the original on 18 April 2006. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- ^ Photograph of Nightingale's grave Archived 23 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine. countryjoe.com

- ^ "Florence Nightingale: The Grave at East Wellow". Countryjoe.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Kelly, Heather (1998). Florence Nightingale's autobiographical notes: A critical edition of BL Add. 45844 (England) Archived 2 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine (M.A. thesis) Wilfrid Laurier University

- ^ Vojnovic, Paola (2013). 'Florence Nightingale: The Lady of the Lamp' in Santa Croce in Pink: Untold Stories of Women and their Monuments. Adriano Antonioletti Boratto. p. 27.

- ^ Bostridge, Mark (2008). Florence Nightingale: The Making of an Icon. Macmillan. p. 1172. ISBN 9781466802926. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ Lewi, Paul J. (2006). Speaking of Graphics. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- ^ Playfair, William; Wainer, Howard; Spence, Ian (2005). Playfair's Commercial and Political Atlas and Statistical Breviary. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521855549.

- ^ a b c d Cohen, I. Bernard (March 1984). "Florence Nightingale". Scientific American. 250 (3): 128–137. Bibcode:1984SciAm.250c.128C. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0384-128. PMID 6367033. S2CID 5409191. (alternative pagination depending on country of sale: 98–107, bibliography on p. 114) online article – see documents link at left Archived 5 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Friendly, Michael (2007). "A.-M. Guerry's Moral Statistics of France: Challenges for Multivariable Spatial Analysis". Statistical Science. 22 (3). Institute of Mathematical Statistics. arXiv:0801.4263. doi:10.1214/07-STS241. S2CID 13536171.

- ^ Wilkinson, Leland (28 January 2006). The Grammar of Graphics. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 209. ISBN 9780387286952. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "Publication explaining Nightingale's use of 'coxcomb'". Archived from the original on 26 November 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ "About us". Royal Statistical Society. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Norman L. Johnson, Samuel Kotz (2011). Leading Personalities in Statistical Sciences: From the Seventeenth Century to the Present". p. 314. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Professional Nursing Practice: Concepts and perspective, Koernig & Hayes, sixth edition, 2011, p. 100.

- ^ Mc Donald, L. (28 January 2010). Florence Nightingale: An Introduction to Her Life and Family: Collected Works of Florence Nightingale. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. pp. 36, 37, 429, 449, etc. ISBN 9780889207042. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ McDonald, Lynn. Florence Nightingale on Public Health Care. p. 550.

- ^ Lambert, Royston (1963). Sir John Simon, 1816–1904. McGibbon & Kee. pp. 521–523.

- ^ Szreter, Simon (1988). "The Importance of Social Intervention in Britain's Mortality Decline c. 1850–1914". Soc. Hist. Med. 1: 1037.

- ^ James Southern, "A Lady 'in Proper Proportions'? Feminism, Lytton Strachey, and Florence Nightingale's Reputation, 1918–39". Twentieth Century British History 28.1 (March 2017): 1–28. doi:10.1093/tcbh/hww047. PMID 28922795.

- ^ Nightingale, Florence (1994). Calabria, Michael D.; MacRae, Janet A. (eds.). Suggestions for Thought: Selections and Commentaries. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1501-4. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ Nightingale, Florence (2008) [1860]. McDonald, Lynn (ed.). Suggestions for Thought. Collected Works of Florence Nightingale. Vol. 11. Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-465-2. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ Collected Works of Florence Nightingale. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ Gilbert, Sandra M., and Susan Gubar. "Florence Nightingale". The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women: The Traditions in English. New York: W. W. Norton, 1996. 836–837.

- ^ "Miss Nightingale – Suffragist". The Vote. 27 August 1910. p. 207. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Eleanor Ross (1972). Welcome, Eumenides. New York: George Braziller. ISBN 9780807606445.

- ^ Rich, Adrienne (1979). On Lies, Secrets, and Silence. New York: W. W. Norton. p. 87. ISBN 9780393012330.

- ^ McDonald, Lynn (ed.). Florence Nightingale: Extending Nursing Collected Works of Florence Nightingale, Volume 13. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-088920520-8.

- ^ Nightingale, Florence (2002). McDonald, Lynn (ed.). Florence Nightingale's Theology: Essays, Letters and Journal Notes. Collected Works of Florence Nightingale. Vol. 3. Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-88920-371-6. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ Miller, Russell E. (1979). The Larger Hope: The first century of the Universalist Church in America 1770–1870. Boston, MA: Unitarian Universalist Association. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-93384-000-3. OCLC 16690792. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2020. — Regarding the influence of Florence Nightingale on Clara Barton.

- ^ Hardy, Susan; Corones, Anthony (2017). "The Nurse's Uniform as Ethopoietic Fashion". Fashion Theory. 21 (5): 523–552. doi:10.1080/1362704X.2016.1203090. S2CID 192947666.

- ^ "Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing & Midwifery: About the School: History". www.kcl.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ "Medals and Badges: Florence Nightingale Medal". British Red Cross. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ^ "Florence Nightingale Medal". International Committee of the Red Cross. 2003. Archived from the original on 1 July 2009. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ "2016 – Nurses: A Force for Change: Improving health systems' resilience". www.icn.ch. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ a b "President gives Florence Nightingale Awards to 35 nurses". Times of India. 13 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ Crathern, Alice Tarbell (1953). "For the Sick". In Detroit Courage Was the Fashion: The Contribution of Women to the Development of Detroit from 1701 to 1951. Wayne University Press. pp. 80–81. ISBN 9780598268259. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "Florence Nightingale Declaration Campaign". Nightingaledeclaration.net. Archived from the original on 10 March 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ "Nightingale Declaration for A Healthy World". Nigh vision. 13 May 2016. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ "Country Joe McDonald's tribute to Florence Nightingale". Countryjoe.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ "Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore – The Rome Campus". .unicatt.it. Archived from the original on 9 September 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ "Cacace, Filippo et. al. "The impact of innovation in medical and nursing training: a Hospital Information System for Students accessible through mobile devices"" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ "Group Florence Nightingale". Groupflorence.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ "Hospital name campaign will honour Florence". Derby Express. 18 August 2011.

- ^ Gilroy, Rebecca (24 March 2020). "New temporary coronavirus hospital in name of Florence Nightingale revealed". Nursing Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "Two more UK facilities to be converted into 'NHS Nightingale' coronavirus hospitals". ITV News. 27 March 2020. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ a b McEnroe, Natasha (9 May 2020). "Celebrating Florence Nightingale's bicentenary". The Lancet. 395 (10235): 1475–1478. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30992-2. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7252134. PMID 32386583.

- ^ "Florence Nightingale". Derby Guide. Archived from the original on 27 May 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ "Nightingale Macmillan Continuing Care Unit". Derby.org.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ "Nurses attend tribute to Florence Nightingale in Derby". BBC News. 11 October 2010. Archived from the original on 9 November 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ Historic England, "Claydon House (1288461)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 26 December 2016

- ^ Historic England, "Claydon (1000597)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 26 December 2016

- ^ "Malvern Museum's Nightingale Exhibit March – October 2010". Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ "Chase pupil wins poster competition". Malvern Gazette. Newsquest Media Group. 21 June 2010. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- ^ "The Florence Nightingale Museum (Istanbul)". Telegraph. 15 September 2007. Archived from the original on 7 March 2010. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ "Florence Nightingale". Florence-nightingale-avenging-angel.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ "New Welsh home confirmed for military medical museum". Military History.org. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ "Commonwealth War Graves Commission Haidar Pasha Cemetery" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ "ESCOLA DE ENFERMAGEM FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE em Anápolis, Anápolis" Archived 10 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine. escolasecreches.com. Retrieved 17 February 2021

- ^ "Florence Nightingale". Wellcome Collection. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

""In aid of the Light Brigade Relief Fund"". British Library. Archived from the original on 8 August 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2021. - ^ Mark Bostridge, Florence Nightingale – The Woman and Her Legend

- ^ "BFI | Film & TV Database | The LADY WITH THE LAMP (1951)". Ftvdb.bfi.org.uk. 16 April 2009. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ Florence Nightingale. Nest Entertainment. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 10 September 2019. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0956136/ Archived 8 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "BBC One presents Florence Nightingale" (Press release). BBC One. 27 February 2008. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ "Mary Seacole Information – Television and Film". www.maryseacole.info. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ ""Foreign Bodies"". Victoria. Season 3. Episode 4. 3 February 2019. PBS.

- ^ "Famous People with Magic Grandad". BroadcastForSchools.co.uk. Archived from the original on 4 November 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ "Florence Nightingale (1985)". Archived from the original on 25 May 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ^ Victoria, Queen of the Screen: From Silent Cinema to New Media. McFarland. 2020. p. 180.

- ^ Allen, Steve. "Jayne Meadows". www.jaynemeadows.com. Archived from the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ "Miss Nightingale". Simply Media. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ The Holy Terror at the TCM Movie Database

- ^ "Tele-Tips – Today". Press-Telegram. 10 February 1952. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b "2012.0003 | Collections Online". collections.thackraymuseum.co.uk. Retrieved 30 May 2024.