Nicarao (cacique)

Macuilmiquiztli | |

|---|---|

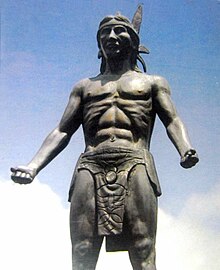

Monument to Macuilmiquiztli in Nicaragua. | |

| Born | 1485 Nicānāhuac |

| Died | 1540 |

| Occupation | Ruler of Kwawkapolkan |

| Known for | Resisting the Spanish conquest of Nicaragua |

Nicarao, or Macuilmiquiztli (Nahuatl Makwilmikistli: macuil "five", miquiztli "death") was the most powerful ruler in pre-Columbian Nicaragua, whose chiefdom stretched from modern-day Rivas in southwestern Nicaragua to Guanacaste province in northwestern Costa Rica.[1][2][3] He was the Nahua chief of Kwawkapolkan, which means "place of capulín trees" in the Nawat language.[4] It's a combination of the Nawat words Kwawit (tree),[5][6] kapol (capulín),[7][8] and -kan (a locative meaning "place of"). Based on research done by historians in 2002, it was discovered that the chief's real name was Macuilmiquiztli, meaning "Five Deaths" in the Nahuatl language.[9][10][11][12] Macuilmiquiztli governed one of the many Nahua chiefdoms in western Nicaragua that the Spanish came to call the Nicaraos, who inhabited a shared land they referred to as Nicānāhuac.[13][14][15][16][17][18]

Biography

[edit]Not much is known about Macuilmiquiztli's background. He was born in Nicānāhuac (western Nicaragua) in 1485. He was intelligent and well educated as well as a talented warrior.[19] According to Spanish conquistadors Gil González Dávila and Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, who was also a historian, Macuilmiquiztli had a cousin named "Wemak" who was the chief of Kakawatan, another Nahua chiefdom in present-day Rivas.[20][21][22][23]

Spanish contact

[edit]At the time of Spanish arrival, Gil González Dávila traveled to western Nicaragua with a small army of just over 100 men made up of conquistadors and their Tlaxcalteca allies. They explored the fertile western valleys and were impressed with the Nahua and Otomanguean civilizations for the vast amounts of food they had in addition to their flourishing markets, permanent temples, and trade network.[20][24][25] Despite the good first impression however, Dávila referred to the Nahuas and Chorotegas as los rojos ("the reds" in Spanish), and their children as rojitos ("little red kids" in Spanish) which were derogatory terms based on skin color.[20] Eventually, Dávila met with Macuilmiquiztli, and conversed with him through Tlaxcalan translators. Macuilmiquiztli initially welcomed the Spanish and their Tlaxcalteca allies. However, Dávila and his army used the opportunity to gather gold and baptize some of the Nahuas along the way, much to Macuilmiquiztli's disapproval. When Dávila demanded the now skeptical Macuilmiquiztli, as well as chiefs Wemak and Diriangén who were also present, to be baptized, to renounce their pagan beliefs, and to hand over the rest of their gold and jewellery, they refused.[20] Realizing the threat that the Spanish imposed, Macuilmiquiztli, as well as the Chorotegas, waged war against the invaders, and Nahua and Chorotega warriors forced Dávila and his men to retreat to Panama.[26][27][28][29] This set the stage for what would become the Spanish conquest of Nicaragua in 1524 CE.

Nahua-Chorotega alliance

[edit]Despite the enmity between the Chorotegas and Nahuas, Macuilmiquiztli and Diriangén made peace and agreed to team up against the Spanish and Tlaxcaltecas. This alliance composed of the Nahua chiefdoms of Kwawkapolkan, Kakawatan and the Otomanguean Chorotegas, all of whom fought together against the Spanish and their central-Mexican allies.[30][31] The Indigenous alliance lost the war however, when Nicaragua was invaded on all sides by several Spanish forces, each led by a conquistador. González Dávila was authorized by royal decree to invade from the Caribbean coast of Honduras. Francisco Hernández de Córdoba at the command of the governor of Panama invaded from Costa Rica. Pedro de Alvarado at the command of Hernán Cortés, came from Guatemala through San Salvador and Honduras.[32] Francisco Hernández de Córdoba fought directly against the alliance, and by 1525 the alliance had completely collapsed. Diriangén escaped the Spanish onslaught but eventually died between 1527-1529, Wemak was captured and executed in 1525 after the last of his Kakawatec forces were annihilated by the conquistadors and Tlaxcaltecas, and the fall of Kwawkapolkan in 1525 finalized their defeat.[33][34]

Legacy and martyrdom

[edit]Macuilmiquiztli and Diriangén remain popular figures in Nicaraguan nationalism and anti-imperialism, so much so that The National Assembly of Nicaragua declared the two Indigenous leaders as national heroes.[35] In addition, Macuilmiquiztli as well as Diriangén are credited with leading the resistance against the Spanish and Tlaxcaltecas, and are symbols of Indigenous resistance against imperialism. Furthermore, their alliance highlights a powerful lesson in teamwork between enemies who set aside their differences and came together to oppose a much greater threat.

Territory

[edit]

The territory or cacicazgo ruled over by Nicarao was situated in the isthmus of what is now known as Nicaragua's Rivas Department, next to Lake Nicaragua, and it extended southward to what is now known as the Guanacaste Province in northwestern Costa Rica. The tribe's capital city or principal settlement was called Kwawkapolkan,[36][37][38][39] though it has sometimes been referred to in history books as Nicaraocallí,[39] and it is believed to have been situated near the modern lake port of San Jorge.

Name controversy and etymology

[edit]In 2002, through the research done by two Nicaraguan historians working independently of each other, it was discovered that the true name of the cacique was actually Macuilmiquiztli, which meant "Five Deaths" in the Nahuatl language.[40] [39][41][42]

It is not known how the name "Nicarao" came to be associated with chief Macuilmiquiztli as the letter "r" does not exist in the Nawat language.[43] The etymology of the term "Nicarao" most likely originated as a shortened and hispanicized form of "Nicānāhuac", the name used by the Nicaraos to refer to western Nicaragua. This is evident in the Spaniards use of the root Nica in "Nicarao" which derives from Nahuatl Nican.[44][45] Andrés de Cereceda, the treasurer of González Dávila's expedition,[39] wrote in his log the names of the caciques of the villages where gold was collected. In the vicinity of Costa Rica's Gulf of Nicoya, they found the largest indigenous village they had visited, which was ruled by a cacique named Chorotega. Since then, linguistic sources have used the name of that cacique as an eponym, "Chorotega people ", to encompass a number of villages which had cultural and linguistic similarities despite being physically separated.

According to a once-popular theory, the name "Nicaragua" was derived from a portmanteau of the name Nicarao and the Spanish word agua which means "water", due to the presence of two large lakes and other bodies of water in the country.[46] However, this theory is considered to be outdated by most historians due to the fact that the cacique's real name was Macuilmiquiztli and not Nicarao. In addition the Nicaraos referred to the land as Nicānāhuac, which most historians now believe is the true etymology of "Nicaragua". It is a combination of the words "Nican" (here),[47] and "Ānāhuac", which in turn is a combination of the words "atl" (water) and "nahuac", a locative meaning "surrounded". Therefore the literal translation of Nicanahuac is "here surrounded by water", fitting the theory that the etymology references the large bodies of water in and around the country, the Pacific Ocean, lakes Nicaragua and Xolotlan, and the rivers and lagoons.[48][49][50][51][52][53]

References

[edit]- ^ "The Kingdom of this world".

- ^ "The Aboriginals of Costa Rica".

- ^ "Las culturas indígenas y su medioambiente".

- ^ "Cocibolca y Xolotlán: Relectura de sus toponimias indígenas" (PDF).

- ^ "Pipil (Nahuat) talking dictionary: tree".

- ^ "living dictionaries: pipil nahuat: tree".

- ^ Campbell, Lyle (January 1, 1985). The Pipil Language of El Salvador. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 10–12. ISBN 978-3-11-088199-8.

- ^ "The history of the word for Cacao in ancient Mesoamerica".

- ^ "Nicarao"

- ^ "Encuentro"

- ^ Sánchez, Edwin (October 3, 2016). "De Macuilmiquiztli al Güegüence pasando por Fernando Silva" [From Macuilmiquizli to Güegüence through Fernando Silva]. El 19 (in Spanish). Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ Silva, Fernando (March 15, 2003). "Macuilmiquiztli". El Nuevo Diario (in Spanish). Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ "Origin of the names of the Latin American countries".

- ^ "The curious story of the origin of the names of Latin American countries".

- ^ "Nicaragua".

- ^ "Nahuatl Dictionary".

- ^ "Etymology of Nicaragua".

- ^ "Nicaraguan place names" (PDF).

- ^ McCafferty and McCafferty 2009

- ^ a b c d Vida de González Dávila, Gil. Ávila, c. 1480 – 21.IV.1526. Descubridor y conquistador. et al., 2012

- ^ Los Indios precolombinos de Nicaragua y Costa Rica en los siglos XV y XVI, 2009 - Bolaños, Enrique

- ^ Historia de la Gran Nicoya en el sur de Mesoamérica, Jiménez-Santana 1997

- ^ Colonización de américa, cuando la historia marcha, de Oviedo y Valdés, Gonzalo c. 1480–1557, 2006

- ^ "The Kingdom Of This World".

- ^ "Costa Rican Archaeology and Mesoamerica" (PDF).

- ^ "Fruit and Axes of Gold Consuming Indigenous Heritages in Nicaragua".

- ^ "The Testimonies and Origins of the Nicaraos" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-03-13. Retrieved 2024-03-03.

- ^ SMITH, JULIAN. "Who Were the People of Greater Nicoya? - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org.

- ^ "About Nicaragua: History up to 1979". www.nicaraguasc.org.uk. Retrieved 2020-03-09.

- ^ Los Indios precolombinos de Nicaragua y Costa Rica en los siglos XV y XVI, 2009 - Bolaños, Enrique

- ^ Historia de la Gran Nicoya en el sur de Mesoamérica, Jiménez-Santana 1997

- ^ Duncan, David Ewing, Hernando de Soto – A Savage Quest in the Americas – Book II: Consolidation, Crown Publishers, Inc., New York, 1995

- ^ Los Indios precolombinos de Nicaragua y Costa Rica en los siglos XV y XVI, 2009 - Bolaños, Enrique

- ^ Historia de la Gran Nicoya en el sur de Mesoamérica, Jiménez-Santana 1997

- ^ "Nicaragua Condemns-Colonialism to Commemorate 500 Years of Indigenous Resistance".

- ^ "Cocibolca y Xolotlán: Relectura de sus toponimias indígenas" (PDF).

- ^ Paul Healy; Mary Pohl (1980). Archaeology of the Rivas Region, Nicaragua. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-88920-094-4.

- ^ Erika Dyck; Christopher Fletcher (October 6, 2015). Locating Health: Historical and Anthropological Investigations of Place and Health. Routledge. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-317-32278-8.

- ^ a b c d "Encuentro del cacique y el conquistador" [Encounter of the cacique and the conqueror]. El Nuevo Diario (in Spanish). April 4, 2009. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ^ Sánchez, Edwin (September 16, 2002). "No hubo Nicarao, todo es invento" [There was no Nicarao, it's all invented]. El Nuevo Diario (in Spanish).

- ^ Sánchez, Edwin (October 3, 2016). "De Macuilmiquiztli al Güegüence pasando por Fernando Silva" [From Macuilmiquizli to Güegüence through Fernando Silva]. El 19 (in Spanish). Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ Silva, Fernando (March 15, 2003). "Macuilmiquiztli". El Nuevo Diario (in Spanish). Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ "Etimología de Nicaragua".

- ^ "nican: NAHUATL DICTIONARY".

- ^ "Ensayos Nicaragüenses" (PDF).

- ^ Sánchez, Edwin (October 16, 2016). "El origen de "Nicarao-agua": la Traición y la Paz" [The origin of "Nicarao-agua": Betrayal and Peace]. El Pueblo Presidente (in Spanish). Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ "Nahuatl Dictionary: Nican".

- ^ "Origin of the names of the Latin American countries".

- ^ "The curious story of the origin of the names of Latin American countries".

- ^ "Nicaragua".

- ^ "Nahuatl Dictionary".

- ^ "Etymology of Nicaragua".

- ^ "Nicaraguan place names" (PDF).