Neo Tokyo (film)

| Neo Tokyo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

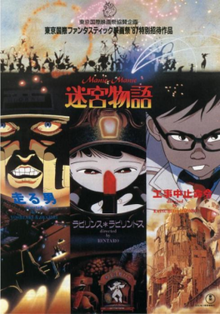

Japanese theatrical poster | |||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 迷宮物語 | ||||

| |||||

| Directed by |

| ||||

| Written by |

| ||||

| Based on | Meikyū Monogatari by Taku Mayumura | ||||

| Produced by | Masao Maruyama Rintaro | ||||

| Starring | |||||

| Cinematography | Kin'ichi Ishikawa | ||||

| Edited by | Harutoshi Ogata | ||||

| Music by | Mickie Yoshino | ||||

Production companies | Madhouse Project Team Argos | ||||

| Distributed by | Toho[1] | ||||

Release date |

| ||||

Running time | 50 minutes | ||||

| Country | Japan | ||||

| Language | Japanese | ||||

Neo Tokyo (迷宮物語, Meikyū Monogatari, literally "Labyrinth Tales"), also titled Manie-Manie on its title card, is a 1987 Japanese adult animated science fiction anthology film produced by Project Team Argos and Madhouse. The film was conceived and produced by Madhouse founders Masao Maruyama and Rintaro, the latter of whom served as composition organizer alongside Katsuhiro Ōtomo on the project.

The 50 minute-long film has three segments, each under a different screenwriter and film director: Rintaro's "Labyrinth Labyrinthos," an exploration into the maze of a little girl's mind, Yoshiaki Kawajiri's "Running Man," focusing on a deadly auto race, and Katsuhiro Ōtomo's "Construction Cancellation Order," a cautionary tale about man's dependency on technology. In addition to original music by Godiego's Mickie Yoshino, two prominently feature famous pieces of Western classical music: the first of Erik Satie's Gymnopédies and the "Toreador Song" of Georges Bizet's Carmen in "Labyrinth" and "Morning Mood" from Edvard Grieg's Peer Gynt score, in an ironic manner, in "The Order."

The film premiered on September 25, 1987, at that year's Tōkyō International Fantastic Film Festival. Other than festival screenings, Japanese distributor Toho originally relegated the film direct-to-video, releasing a VHS on October 10, 1987, but did eventually give it a general cinema release in Japan, on April 15, 1989. In English, the film was licensed, dubbed and released theatrically (as a double feature with the first Silent Möbius film) and to VHS in North America by Streamline Pictures, the license later being taken up by the now also out of business ADV Films.[2]

Plot

[edit]Labyrinth Labyrinthos

[edit]In the film's frame story, a girl named Sachi (Hideko Yoshida/Cheryl Chase) plays a game of hide-and-seek with her cat Cicerone. The game leads them to an old longcase clock, which doubles as a doorway to a labyrinth world filled with supernatural oddities and characters. Eventually, Sachi and Cicerone arrive at a circus tent, where they watch the following segments on a viewing screen. After the following segments conclude, the circus troupe performs a show for the two. However, it is then revealed Sachi and Cicerone were watching the entire film unfold on a television in the void of space.

The Running Man

[edit]Zack Hugh (Toshiyuki Morikawa/Jeff Winkless) has dominated the Death Circus racing circuit for 10 years. Journalist Bob Stone (Masane Tsukayama/Michael McConnohie) discovers Zack possesses telekinetic abilities, which he uses to destroy the other racers. After winning his latest race by killing the competitors, Zack hallucinates being overtaken by a spectral racer and destroys himself when he attempts to use his powers on the hallucination. The Death Circus is shut down afterwards, with Bob theorizing spectators wanted to see how long Zack could outlast death.

Construction Cancellation Order

[edit]A revolution in the fictional South American country of the Aloana Republic results in a new government that refuses to accept a contract for the construction of a city-sized project called Facility 444 in an inhospitable swamp. Salaryman Tsutomu Sugioka (Yū Mizushima/Robert Axelrod) is sent to stop the construction, which is being performed by robots under the command of an increasingly erratic robot designated 444-1 (Hiroshi Ōtake/Jeff Winkless). Witnessing the destruction of several robots and 444-1's refusal to cease operations, Tsutomu begins to lose his patience and is nearly killed by 444-1, who was programmed to eliminate anything that poses a threat to the project. Tsutomu retaliates by destroying 444-1 and follows its power cord to the energy source of the robots in an attempt to finally end the construction. Unknown to Tsutomu, the old government has been restored and is again honoring the contract.

Production

[edit]Labyrinth Labyrinthos

[edit]Labyrinth Labyrinthos (ラビリンス*ラビリントス, Rabirinsu Rabirintosu) is written for the screen and directed by Rintaro, with character design and animation direction by Atsuko Fukushima and art direction by Yamako Ishikawa.[1] It serves as the anthology's "top-level" story, a framing device that leads into the other two works.

The Running Man

[edit]Running Man (走る男, Hashiru Otoko) is written for the screen and directed by Yoshiaki Kawajiri, with character design and animation direction by Kawajiri, mechanical design by Takashi Watabe and Satoshi Kumagai, key animation by Shinji Otsuka, Nobumasa Shinkawa, Toshio Kawaguchi and Kengo Inagaki and art direction by Katsushi Aoki.[1] The segment appeared on Episode 205 of Liquid Television, which featured Rafael Ferrer replacing Michael McConnohie as Bob Stone.

Construction Cancellation Order

[edit]Construction Cancellation Order (工事中止命令, Kōji Chūshi Meirei) is written for the screen and directed by Katsuhiro Otomo, with character designs by Otomo and animation direction by Takashi Nakamura[1] This segment's depiction of South America as a dangerous, unstable place is comparable to other depictions in the Japanese media during the 1990s such as Osamu Tezuka's 1987 comic Gringo.

Reception

[edit]In a 2021 list of the "100 best anime movies of all-time", Paste magazine ranked Neo Tokyo at #11, writing "though for the most part absent of any real thematic connectivity, Neo-Tokyo is a concise and powerful example of the dizzying heights of technical mastery and aesthetic ambition anime can achieve when put in the hands of the medium's most inimitable creators."[3]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Original-language opening and closing credits of the film in question, most of the latter of which are transcribed [here https://auduki.bluette.info/list/mekyustory.html] as of August 25, 2011. These have been checked as accurate against a transfer of the film though do not fully reflect their order and formatting in it.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (2009). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons (3rd ed.). New York: Checkmark Books. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-8160-6600-1.

- ^ Egan, Toussaint; DeMarco, Jason (27 April 2021). "The 100 Best Anime Movies of All Time". Paste. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

External links

[edit]- 1987 films

- 1987 anime films

- 1987 anime OVAs

- 1987 science fiction films

- Animated cyberpunk films

- Cyberpunk anime and manga

- Cyberpunk films

- Films based on multiple works

- Animated films based on short fiction

- Films directed by Yoshiaki Kawajiri

- Films directed by Katsuhiro Otomo

- Films directed by Rintaro

- Animated films set in South America

- Japanese anthology films

- Japanese auto racing films

- Japanese animated science fiction films

- Madhouse (company)

- Animated films about auto racing

- Animated anthology films

- Japanese robot films

- Films about telekinesis

- Toho animated films

- ADV Films

- Japanese adult animated films

- Adult animated science fiction films