People's Liberation Army Navy

| People's Liberation Army |

|---|

|

| Executive departments |

| Staff |

| Services |

| Arms |

| Domestic troops |

| Special operations force |

| Military districts |

| History of the Chinese military |

| Military ranks of China |

The People's Liberation Army Navy,[a] also known as the People's Navy, PLA Navy or simply Chinese Navy, is the naval warfare branch of the People's Liberation Army, the national military of the People's Republic of China. It is composed of five sub-branches: the Surface Force, the Submarine Force, the Coastal Defense Force, the Marine Corps and the Naval Air Force, with a total strength of 350,000 personnel, including 70,000 marines and 30,000 naval aviation personnel.[5] The PLAN's combat units are deployed among three theater command fleets, namely the North Sea, East Sea and South Sea Fleet, which serve the Northern, Eastern and Southern Theater Command, respectively.

The PLAN was formally established on 23 April 1949[6] and traces its lineage to maritime fighting units during the Chinese Civil War, including many elements of the Republic of China Navy which had defected. Until the late 1980s, the PLAN was largely a riverine and littoral force (brown-water navy) mostly in charge of coastal defense and patrol against potential Nationalist amphibious invasions and territorial waters disputes in the East and South China Sea (roles that are now largely relegated to the paramilitary China Coast Guard), and had been traditionally a maritime support subordinate to the PLA Ground Force. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Chinese leadership were freed from overland border concerns with the northern neighbor and shifted towards more forward-oriented foreign and national security policies in the 1990s, and the PLAN leaders were able to advocate for renewed attention toward limited command of the seas as a green-water navy operating in the marginal seas within the range of coastal air parity.

Into the 21st century, Chinese military officials have outlined plans to operate with blue water capability between the first and second island chains,[7] with Chinese strategists talking about the modernization of the PLAN into "a regional blue-water defensive and offensive navy."[8] Transitioning into a blue-water navy, regular naval exercises and patrols have increased in the Taiwan Strait, the Senkaku Islands/Diaoyutai in the East China Sea, and within the nine-dash line in the South China Sea, and all of which China claims as its territory[9][10][11] despite the Republic of China (ROC, i.e. Taiwan), Vietnam, Brunei, Malaysia and the Philippines each also claiming a significant part of the South China Sea.[12][13] Some exercises and patrols of the PLAN in recent years went as close as the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of Japan, Taiwan, and Alaska although undisputed territorial waters have been not been crossed except in cases of innocent passage.[14][15][16][17]

As of 2024[update], the PLAN is the second-largest navy in the world by total displacement tonnage[18] — at 2 million tons in 2024, behind only the United States Navy (USN)[19] — and the largest navy globally by number of active sea-going ships (excluding coastal missile boats, gunboats and minesweepers)[20][21] with over 370 surface ships and submarines in service,[22] compared to approximately 292 ships and submarines in the USN.[23] However, the Chinese fleets are much newer and smaller in tonnage, as about 70% of their warships were launched after 2010 and consist mostly of newly designed destroyers, frigates and corvettes with only a few amphibious warfare ships and the two commissioned aircraft carriers, while only about 25% of the American ships were launched after 2010 and majority of their tonnage are from its eleven 100,000-ton supercarriers, 21 large amphibious assault ships and experimental capital ships such as the Zumwalt-class destroyers.[24] The dominance of Chinese shipbuilding capacity (over 230 times greater than the United States, according to the Alliance for American Manufacturing[25]) have led the Office of Naval Intelligence to project that China will have 475 battle force ships by 2035 while the USN will have 305 to 317,[26] which would put the United States in a numerical and operational disadvantage especially in the West Pacific according to a chair naval strategy professor at the Naval War College.[27]

History

[edit]

The PLAN traces its lineage to units of the Republic of China Navy (ROCN) who defected to the People's Liberation Army towards the end of the Chinese Civil War. A number of Japanese and Manchukuo Imperial Navy gunboats used to patrol the river border with the Soviet Union were also handed over to the PLA following the surrender of Japan. In 1949, Mao Zedong asserted that "to oppose imperialist aggression, we must build a powerful navy". During the Landing Operation on Hainan Island, the communists used wooden junks fitted with mountain guns as both transport and warships against the ROCN. The navy was established on 23 April 1949 by consolidating regional naval forces under Joint staff Department command in Jiangyan (now in Taizhou, Jiangsu).[6]

The Naval Academy was set up at Dalian on 22 November 1949, mostly with Soviet instructors. It then consisted of a motley collection of ships and boats acquired from the Kuomintang forces. The Naval Air Force was added two years later. By 1954, an estimated 2,500 Soviet naval advisers were in China—possibly one adviser to every thirty Chinese naval personnel—and the Soviet Union began providing modern ships.

With Soviet assistance, the navy reorganized in 1954 and 1955 into the North Sea Fleet, East Sea Fleet, and South Sea Fleet, and a corps of admirals and other naval officers was established from the ranks of the ground forces. In shipbuilding the Soviets first assisted the Chinese, then the Chinese copied Soviet designs without assistance, and finally the Chinese produced vessels of their own design. Eventually Soviet assistance progressed to the point that a joint Sino-Soviet Pacific Ocean fleet was under discussion.

1950s and 1960s

[edit]Through the upheavals of the late 1950s and 1960s the Navy remained relatively undisturbed. Under the leadership of Minister of National Defense Lin Biao, large investments were made in naval construction during the frugal years immediately after the Great Leap Forward. During the Cultural Revolution, a number of top naval commissars and commanders were purged.

Naval forces were used to suppress a revolt in Wuhan in July 1967, but the service largely avoided the turmoil affecting the country. Although it paid lip service to Mao and assigned political commissars aboard ships, the Navy continued to train, build, and maintain the fleets as well the coastal defense and aviation arms, as well as in the performance of its mission.

1970s and 1980s

[edit]In the 1970s, when approximately 20 percent of the defense budget was allocated to naval forces, the Navy grew dramatically. The conventional submarine force increased from 35 to 100 boats, the number of missile-carrying ships grew from 20 to 200, and the production of larger surface ships, including support ships for oceangoing operations, increased. The Navy also began development of nuclear attack submarines (SSN) and nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBN).[citation needed]

In the 1980s, under the leadership of Chief Naval Commander Liu Huaqing, the navy developed into a regional naval power, though naval construction continued at a level somewhat below the 1970s rate. Liu Huaqing was an Army officer who spent most of his career in administrative positions involving science and technology. It was not until 1988 that the People's Liberation Army Navy was led by a naval officer. Liu was also very close to Deng Xiaoping as his modernization efforts were very much in keeping with Deng's national policies.[28]

While under his leadership Naval construction yards produced fewer ships than the 1970s, greater emphasis was placed on technology and qualitative improvement. Modernization efforts also encompassed higher educational and technical standards for personnel; reformulation of the traditional coastal defense doctrine and force structure in favor of more green-water operations; and training in naval combined-arms operations involving submarine, surface, naval aviation, and coastal defense forces.[28]

Examples of the expansion of China's capabilities were the 1980 recovery of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) in the Western Pacific by a twenty-ship fleet, extended naval operations in the South China Sea in 1984 and 1985, and the visit of two naval ships to three South Asian nations in 1985. In 1982 the navy conducted a successful test of an underwater-launched ballistic missile. The navy also had some success in developing a variety of surface-to-surface and air-to-surface missiles, improving basic capabilities.[28]

In 1986, the Navy's order of battle included two Xia-class SSBNs armed with twelve CSS-N-3 missiles and three Han-class SSNs armed with six SY-2 cruise missiles. In the late 1980s, major deficiencies reportedly remained in anti-submarine warfare, mine warfare, naval electronics (including electronic countermeasures equipment), and naval aviation capabilities.[citation needed]

The PLA Navy was ranked in 1987 as the third largest navy in the world, although naval personnel had comprised only 12 percent of PLA strength. In 1987 the Navy consisted (as it does now) of the naval headquarters in Beijing; three fleet commands – the North Sea Fleet, based at Qingdao, Shandong; the East Sea Fleet, based at Ningbo; and the South Sea Fleet, based at Zhanjiang, Guangdong – and about 1,000 ships of which only approximately 350 are ocean going. The rest are small patrol or support craft.[citation needed]

The 350,000-person Navy included Naval Air Force units of 34,000 men, the Coastal Defense Forces of 38,000, and the Marine Corps of 56,500. Navy Headquarters, which controlled the three fleet commands, was subordinate to the PLA General Staff Department. In 1987, China's 1,500 km coastline was protected by approximately 70[citation needed] diesel-powered Romeo- and Whiskey-class submarines, which could remain at sea only a limited time.

Inside this protective ring and within range of shore-based aircraft were destroyers and frigates mounting Styx anti-ship missiles, depth-charge projectors, and guns up to 130 mm. Any invader penetrating the destroyer and frigate protection would have been swarmed by almost 900 fast-attack craft. Stormy weather limited the range of these small boats, however, and curtailed air support. Behind the inner ring were Coastal Defense Force personnel operating naval shore batteries of Styx missiles and guns, backed by ground force units deployed in depth.[citation needed]

1990s and 2000s

[edit]As the 21st century approached, the PLAN began to transition to an off-shore defensive strategy that entailed more out-of-area operations away from its traditional territorial waters.[29]: 23–30 From 1990 to 2002, Jiang Zemin's military reforms placed particular emphasis on the Navy.[30]: 261

Between 1989 and 1993, the training ship Zhenghe paid ports visits to Hawaii, Thailand, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and India. PLAN vessels visited Vladivostok in 1993, 1994, 1995, and 1996. PLAN task groups also paid visits to Indonesia in 1995; North Korea in 1997; New Zealand, Australia, and the Philippines in 1998; Malaysia, Tanzania, South Africa, the United States, and Canada in 2000; and India, Pakistan, France, Italy, Germany, Britain, Hong Kong, Australia, and New Zealand in 2001.[29]: 114

In March 1997, the Luhu-class guided missile destroyer Harbin, the Luda-class guided missile destroyer Zhuhai, and the replenishment oiler Nancang began the PLA Navy's first circumnavigation of the Pacific Ocean, a 98-day voyage with port visits to Mexico, Peru, Chile, and the United States, including Pearl Harbor and San Diego. The flotilla was under the command of Vice Admiral Wang Yongguo, the commander-in-chief of the South Sea Fleet.[29]: 114 [31][32][33]

The Luhu-class guided missile destroyer Qingdao and the replenishment oiler Taicang completed the PLA Navy's first circumnavigation of the world (pictured), a 123-day voyage covering 32,000 nautical miles (59,000 km; 37,000 mi) between 15 May – 23 September 2002. Port visits included Changi, Singapore; Alexandria, Egypt; Aksis, Turkey; Sevastopol, Ukraine; Piraeus, Greece; Lisbon, Portugal; Fortaleza, Brazil; Guayaquil, Ecuador; Callao, Peru; and Papeete in French Polynesia. The PLA naval vessels participated in naval exercises with the French frigates Nivôse and Prairial, as well as exercises with the Peruvian Navy. The flotilla was under the command of Vice Admiral Ding Yiping, the commander-in-chief of the North Sea Fleet, and Captain Li Yujie was the commanding officer of the Qingdao.[29]: 114–115 [34][35][36]

Overall, between 1985 and 2006, PLAN naval vessels visited 18 Asian-Pacific nations, 4 South American nations, 8 European nations, 3 African nations, and 3 North American nations.[29]: 115 In 2003, the PLAN conducted its first joint naval exercises during separate visits to Pakistan and India. Bi-lateral naval exercises were also carried out with exercises with the French, British, Australian, Canadian, Philippine, and United States navies.[29]: 116

On 26 December 2008, the PLAN dispatched a task group consisting of the guided missile destroyer Haikou (flagship), the guided missile destroyer Wuhan, and the supply ship Weishanhu to the Gulf of Aden to participate in anti-piracy operations off the coast of Somalia. A team of 16 Chinese Special Forces members from its Marine Corps armed with attack helicopters were on board.[37][38][39] Since then, China has maintained a three-ship flotilla of two warships and one supply ship in the Gulf of Aden by assigning ships to the Gulf of Aden on a three monthly basis. Other recent PLAN incidents include the 2001 Hainan Island incident, a major submarine accident in 2003, and naval incidents involving the U.S. MSC-operated ocean surveillance ships Victorious and Impeccable during 2009. At the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the PLAN, 52 to 56 vessels were shown in manoeuvres off Qingdao in April 2009 including previously unseen nuclear submarines.[40][41]

The demonstration was seen as a sign of the growing status of China, while the CMC chairman, Hu Jintao, indicated that China is neither seeking regional hegemony nor entering an arms race.[40] Predictions by Western analysts that the PLAN would outnumber the USN submarine force as early as 2011 have failed to come true because the PRC curtailed both imports and domestic production of submarines.[42]

2010s and 2020s

[edit]

Beginning in 2009, China ordered 4 Zubr-class LCAC from Ukraine and bought 4 more from the Hellenic Navy (Greece). These hovercraft/LCACs are built to send troops and armored vehicles (tanks, etc.) onto beaches in a fast manner, acting as a landing craft, and were viewed to be a direct threat to Taiwan's pro-independence movement as well as the conflict over Senkaku Islands. China is continually shifting the power balance in Asia by building up the Navy's Submarines, Amphibious warfare, and surface warfare capabilities.[citation needed]

Between 5–12 July 2013, a seven-ship task force from the North Sea Fleet joined warships from the Russian Pacific Fleet to participate in Joint Sea 2013, bilateral naval maneuvers held in the Peter the Great Bay of the Sea of Japan. To date, Joint Sea 2013 was the largest naval drill yet undertaken by the People's Liberation Army Navy with a foreign navy.[44]

On 2 April 2015, during the violent aftermath of a coup d'état in Yemen and amid an international bombing campaign, the PLAN helped ten countries get their citizens out of Yemen safely, evacuating them aboard a missile frigate from the besieged port city of Aden. The operation was described by Reuters as "the first time that China's military has helped other countries evacuate their people during an international crisis".[45]

China's participation in international maritime exercises is also increasing. In RIMPAC 2014, China was invited to send ships from their People's Liberation Army Navy; marking not only the first time China participated in a RIMPAC exercise but also the first time China participated in a large-scale United States-led naval drill.[46] On 9 June 2014, China confirmed it would be sending four ships to the exercise, a destroyer, frigate, supply ship, & hospital ship.[47][48] In April 2016, the People's Republic of China was also invited to RIMPAC 2016 despite the tension in South China Sea.[49]

PRC military expert Yin Zhuo said that due to present weaknesses in the PLAN's ability to replenish their ships at sea, their future aircraft carriers will be forced to operate in pairs.[50] In a TV interview, Zhang Zhaozhong suggest otherwise, saying China is "unlikely to put all her eggs in one basket" and that the navy will likely rotate between carriers rather than deploy them all at once.

In 2017, PLAN hospital ship Peace Ark traveled to Djibouti (treating 7,841 Djiboutians), Sierra Leone, Gabon, Republic of Congo (treating 7,508 Congolese), Angola, Mozambique (treating 9,881 Mozambiquans), and Tanzania (treating 6,421 Tanzanians).[51]: 284

The PLAN continued its expansion into the 2020s, increasing its operational capacity, commissioning new ships, and constructing naval facilities.[52] Observers note that the PLAN's ongoing modernization is intended to build up the Chinese surface fleet and fix existing issues that limit the capability of the PLAN. Observers have noted that the PLAN's expansion will allow it to project Chinese power in the South China Sea and allow for the navy to counter the USN's operations in Asia.[53] Chinese naval capability increased substantially in the 2010s and 2020s. According to the US-based think tank RAND Corporation, PLAN enjoyed major advantages in terms of naval technologies, missiles, and tonnage against regional rivals such as Taiwan, Japan, Vietnam, the Philippines, and India.[citation needed]

Organization

[edit]

The PLAN is organized into several departments for purposes of command, control and coordination. Main operating forces are organized into fleets, each with its own headquarters, a commander (a Rear Admiral or Vice Admiral) and a Political Commisar. All PLAN headquarters are subordinate to the PLA Joint Staff Department and the Chairman of the Central Military Commission.

The navy has 240,000 personnel, including 15,000 marines.[30]: 263

Fleets

[edit]The People's Liberation Army Navy is divided into three fleets:

- The North Sea Fleet, based in the Yellow Sea and headquartered in Qingdao, Shandong.

- The East Sea Fleet, based in the East China Sea and headquartered in Ningbo, Zhejiang.

- The South Sea Fleet, based in the South China Sea and headquartered in Zhanjiang, Guangdong.

Branches

[edit]PLAN Surface Force

[edit]

The People's Liberation Army Surface Force consists of all surface warships in service with the PLAN. They are organised into flotillas spread across the three main fleets.[citation needed]

PLAN Submarine Force

[edit]The People's Liberation Army Navy Submarine Force consists of all nuclear and diesel-electric submarines in service with the PLAN.

The PRC is the last of the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council which has not conducted an operational ballistic missile submarine patrol, because of institutional problems.[54] It operates a fleet of 68 submarines.

PLAN Coastal Defence Force

[edit]The PLAN Coastal Defence Force is a land-based branch of the PLAN in charge of coastal defence,[citation needed] with a strength of around 25,000 personnel. Also known as the coastal defense troops, they serve to defend China's coastal and littoral areas from invasion via amphibious landings or air attacks.

Between the 1950s and 1960s, the Coastal Defense Force was primarily assigned to repel any Kuomintang attempts to infiltrate, invade and harass the Chinese coastline. After the Sino-Soviet split and the abandonment of KMT's plans to recapture the Mainland, the Coastal Defense Force was focused on defending China's coast from a possible Soviet sea-borne invasion throughout the 1960s to 1980s.

With the fall of the Soviet Union, the threat of an amphibious invasion of China has diminished and therefore the branch is often considered to no longer be a vital component of the PLAN, especially as the surface warships of the PLAN continue to improve in terms of anti-ship and air-defence capabilities and the PLAN's power projection begins to extend beyond the first island chain.

Today the primary weapons of the coastal defense troops are the HY-2, YJ-82 and C-602 anti-ship missiles.

PLAN Marine Corps

[edit]

The PLAN Marine Corps was originally established in the 1950s and then re-established in 1979 under PLAN organisation. It consists of around 20,000 marines,[55] and is based in the South China Sea with the South Sea Fleet. The Marine Corps are considered elite troops, and are rapid deployment forces trained primarily in amphibious warfare and sometimes in air assaults to establish a beachhead or act as a spearhead during assault operations against enemy targets.

The marines are equipped with the standard Type 95 assault rifles as well as other small arms and personnel equipment, and a blue/littoral camouflage uniform as standard. The marines are also equipped with amphibious armoured fighting vehicles (including amphibious light tanks such as the Type 63, assault vehicles such as the ZTD-05 and IFVs such as ZBD-05), helicopters, naval artillery, anti-aircraft weapon systems and short range surface-to-air missiles.

With the PLAN's accelerating efforts to expand its capabilities beyond territorial waters, it would be likely for the Marine Corps to play a greater role in terms of being an offshore expeditionary force similar to the USMC and Royal Marines.

PLAN Air Force

[edit]The People's Liberation Army Naval Air Force (PLANAF) is the naval aviation branch of the PLAN and has a strength of around 25,000 personnel and 690 aircraft. It operates similar hardwares to the People's Liberation Army Air Force, including fighter aircraft, bombers, attack aircraft, tankers, reconnaissance/early warning aircraft, electronic warfare aircraft, maritime patrol aircraft, transport aircraft and helicopters of various roles.

The PLA Naval Air Force has traditionally operated from coastal air bases, and received older aircraft than the PLAAF with less ambitious steps towards mass modernization. Advancements in new technologies, weaponry and aircraft acquisition were made after 2000. With the introduction of China's first aircraft carrier, Liaoning, in 2012, the Naval Air Force is conducting carrier-based operations for the first time[56] with the goal of building carrier battle group-focused blue water capabilities.

The PLANAF naval air bases include:

- North Sea Fleet: Dalian, Qingdao, Jinxi, Jiyuan, Laiyang, Jiaoxian, Xingtai, Laishan, Anyang, Changzhi, Liangxiang and Shan Hai Guan

- East Sea Fleet: Danyang, Daishan, Shanghai (Dachang), Ningbo, Luqiao, Feidong and Shitangqiao

- South Sea Fleet: Foluo, Haikou, Lingshui, Sanya, Guiping, Jialaishi and Lingling

Relationship with other maritime organizations of China

[edit]The PLAN is complemented by paramilitary maritime services such as the China Coast Guard. The Chinese Coast Guard was previously not under an independent command, considered part of the People's Armed Police, under the local (provincial) border defense command, prior to its reorganization and consolidation as an unified service. It was formed from the integration of several formerly separate services such as China Marine Surveillance (CMS), General Administration of Customs, Armed Police, China Fishery Law Enforcement and local maritime militia.

The CMS performed mostly coastal and ocean search and rescue or patrols, and received quite a few large patrol ships that significantly enhanced their operations; while Customs, militia, Armed Police and Fishery Law Enforcement operated hundreds of small patrol craft. For maritime patrol services, these craft are usually quite well armed with machine guns and 37mm anti-aircraft guns. In addition, these services operated their own small aviation fleets to assist their maritime patrol capabilities, with Customs and CMS operating a handful of Harbin Z-9 helicopters, and a maritime patrol aircraft based on the Harbin Y-12 STOL transport.

Every coastal province has 1 to 3 Coast Guard squadrons:

- 3 Squadrons: Fujian, Guangdong

- 2 Squadrons: Liaoning, Shandong, Zhejiang, Hainan, Guangxi

- 1 Squadron: Heibei, Tianjin, Jiangsu, Shanghai

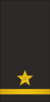

Ranks

[edit]The ranks in the People's Liberation Army Navy are similar to those of the People's Liberation Army Ground Force, Air Force and the Rocket Force. The current system of officer ranks and insignia dates from 1988 and is a revision of the ranks and insignia used from 1955 to 1965. The rank of Hai Jun Yi Ji Shang Jiang (First Class Admiral) was never held and was abolished in 1994. With the official introduction of the Type 07 uniforms all officer insignia are on either shoulders or sleeves depending on the type of uniform used. The current system of enlisted ranks and insignia dates from 1998.

Commissioned officer ranks

[edit]The rank insignia of commissioned officers.

| Rank group | General / flag officers | Senior officers | Junior officers | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| 海军上将 Hǎijūn shàngjiàng |

海军中将 Hǎijūn zhōngjiàng |

海军少将 Hǎijūn shàojiàng |

海军大校 Hǎijūn dàxiào |

海军上校 Hǎijūn shàngxiào |

海军中校 Hǎijūn zhōngxiào |

海军少校 Hǎijūn shàoxiào |

海军上尉 Hǎijūn shàngwèi |

海军中尉 Hǎijūn zhōngwèi |

海军少尉 Hǎijūn shàowèi | |||||||||||||||

Other ranks

[edit]The rank insignia of non-commissioned officers and enlisted personnel.

| Rank group | Senior NCOs | Junior NCOs | Enlisted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 海军一级军士长 Hǎijūn yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军二级军士长 Hǎijūn èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军三级军士长 Hǎijūn sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军四级军士长 Hǎijūn sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军上士 Hǎijūn shàngshì |

海军中士 Hǎijūn zhōngshì |

海军下士 Hǎijūn xiàshì |

海军上等兵 Hǎijūn shàngděngbīng |

海军列兵 Hǎijūn lièbīng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Commanders

[edit]- Xiao Jinguang (January 1950 − January 1980)

- Ye Fei (January 1980 – August 1982)

- Liu Huaqing (August 1982 – January 1988)

- Zhang Lianzhong (January 1988 – November 1996)

- Shi Yunsheng (November 1996 – June 2003)

- Zhang Dingfa (June 2003 – August 2006)

- Wu Shengli (August 2006 – January 2017)

- Shen Jinlong (January 2017 – September 2021)

- Dong Jun (September 2021 – December 2023)

- Hu Zhongming (December 2023–present)

Contemporary topics

[edit]Strategy, plans, priorities

[edit]

The People's Liberation Army Navy has become more prominent in recent years owing to a change in Chinese strategic priorities. The new strategic threats include possible conflict with the United States and/or a resurgent Japan in areas such as the Taiwan Strait or the South China Sea. As part of its overall program of naval modernization, the PLAN has a long-term plan of developing a blue water navy. Robert D. Kaplan has said that it was the collapse of the Soviet Union that allowed China to transfer resources from its army to its navy and other force projection assets.[58]

China is constructing a major underground nuclear submarine base near Sanya, Hainan. In December 2007 the first Type 094 submarine was moved to Sanya.[59] The Daily Telegraph on 1 May 2008 reported that tunnels were being built into hillsides which could be capable of hiding up to 20 nuclear submarines from spy satellites. According to the Western news media the base is reportedly to help China project seapower well into the Pacific Ocean area, including challenging United States naval power.[60][61]

During a 2008 interview with the BBC, Major General Qian Lihua, a senior Chinese defense official, stated that the PLAN aspired to possess a small number of aircraft carriers to allow it to expand China's air defense perimeter.[62] According to Qian the important issue was not whether China had an aircraft carrier, but what it did with it.[62] On 13 January 2009, Adm. Robert F. Willard, head of the U.S. Pacific Command, called the PLAN's modernization "aggressive," and that it raised concerns in the region.[63] On 15 July 2009, Senator Jim Webb of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee declared that only the "United States has both the stature and the national power to confront the obvious imbalance of power that China brings" to situations such as the claims to the Spratly and Paracel islands.[64]

Ronald O'Rourke of the Congressional Research Service wrote in 2009 that the PLAN "continues to exhibit limitations or weaknesses in several areas, including capabilities for sustained operations by larger formations in distant waters, joint operations with other parts of China’s military, C4ISR systems, anti-air warfare (AAW), antisubmarine warfare (ASW), MCM, and a dependence on foreign suppliers for certain key ship components."[65]

In 1998 China purchased the discarded Ukrainian ship Varyag and began retrofitting it for naval deployment. On 25 September 2012, the People's Liberation Army Navy took delivery of China's first aircraft carrier, the CNS Liaoning.[66] The 60,000-ton ship can accommodate 33 fixed wing aircraft. It is widely speculated that these aircraft will be the J15 fighter (the Chinese version of Russia's SU-33).[67]

In September 2015, satellite images showed that China may have started constructing its first indigenous Type 002 aircraft carrier. At the time, the layout suggested to be displacement of 50,000 tons and a hull to have a length of about 240 m and a beam of about 35 m.[68] On 28 April 2017 the carrier was launched as the CNS Shandong.

Japan has raised concerns about the PLAN's growing capability and the lack of transparency as its naval strength keeps on expanding.[69] China has entered into service the world's first anti-ship ballistic missile called DF-21D. The potential threat from the DF-21D against U.S. aircraft carriers has reportedly caused major changes in U.S. strategy.[70]

On 28 June 2017 China launched the first of a new type of large destroyer, the Type 055 destroyer. The destroyer – the CNS Nanchang – is, with its length of 180 m and at over 12,000 tons fully loaded, the second largest destroyer class in the world after the American Zumwalt-class destroyer.[71] Eight destroyers to this design, rated by the United States Navy as "cruisers", have been built or are under construction.

Comparison to US Navy

[edit]The strength of PLAN is often compared to that of the US Navy. PLAN is the second largest navy in the world in terms of tonnage which stands at 2 million tons as of 2022,[19] only behind the United States Navy. PLAN has the largest number of major surface combatants of any navy globally with an overall battle force of approximately 350 surface ships and submarines – in comparison, the United States Navy's battle force is approximately 293 ships.[72]

Attempts have been made to compare PLAN's firepower with the USN. A 2019 review found the USN fleet was able to deploy more "battle force missiles" (BFMs), defined as those missiles that contribute to battle missions, than the PLAN: USN fleet could deploy 11,000 BFMs, compared to 5250 BFMs for PLAN and 3326 BFMs for the Russian Navy.[73] A 2016 review concluded that PLAN's missiles had higher firepower than the USN's, measured in terms of "strike-mile", the ability to delivery a warhead using anti-ship missiles (ASM) across a given distance.[74] The review used the following formula for every ASM the navy had in its inventory:

- Total strike-miles=(Range of an ASM × Warhead weight of an ASM) × Number of such missiles carried by a warship × Number of such warships in the navy

It concluded the total firepower of the PLAN was 77 million strike-miles compared to 17 million strike-miles of the USN.[74]

Territorial disputes

[edit]

Spratly Islands dispute

[edit]The Spratly Islands dispute is a territorial dispute over the ownership of the Spratly Islands, a group of islands located in the South China Sea. States staking claims to various islands are Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Vietnam, and People's Republic of China. All except Brunei occupy some of the islands in dispute. The People's Republic of China conducted naval patrols in the Spratly Islands and established a permanent base.

On 14 March 1988, Chinese and Vietnamese naval forces clashed over Johnson South Reef in the Spratly Islands, which involved three PLAN frigates.[citation needed]

In February 2011, the Chinese frigate Dongguan fired three shots at Philippine fishing boats in the vicinity of Jackson Atoll. The shots were fired after the frigate instructed the fishing boats to leave, and one of those boats experienced trouble removing its anchor.[75][76] In May 2011, the Chinese patrol boats attacked and cut the cable of Vietnamese oil exploration ships near Spratly islands. The incidence sparked several anti-China protests in Vietnam. In June 2011, the Chinese navy conducted three days of exercises, including live fire drills, in the disputed waters. This was widely seen as a warning to Vietnam, which had also conducted live fire drills near the Spratly Islands. Chinese patrol boats fired repeated rounds at a target on an apparently uninhabited island, as twin fighter jets streaked in tandem overhead. 14 vessels participated in the maneuvers, staging antisubmarine and beach landing drills aimed at "defending atolls and protecting sea lanes."[citation needed]

In May 2013, the Chinese navy's three operational fleets deployed together for the first time since 2010. This combined naval maneuvers in the South China Sea coincided with the ongoing Spratly Islands dispute between China and the Philippines as well as deployment of the U.S. Navy's Carrier Strike Group Eleven to the U.S. Seventh Fleet.[citation needed]

Senkaku Islands dispute

[edit]The Senkaku Islands dispute concerns a territorial dispute over a group of uninhabited islands known as the Diaoyu Islands in China, the Senkaku Islands in Japan,[77] and Tiaoyutai Islands in Taiwan.[78] Aside from a 1945 to 1972 period of administration by the United States, the archipelago has been controlled by Japan since 1895.[79] The People's Republic of China disputed the proposed U.S. handover of authority to Japan in 1971[80] and has asserted its claims to the islands since that time.[81] Taiwan also has claimed these islands. The disputed territory is close to key shipping lanes and rich fishing grounds, and it may have major oil reserves in the area.[82]

On some occasions, ships and planes from various mainland Chinese and Taiwanese government and military agencies have entered the disputed area. In addition to the cases where they escorted fishing and activist vessels, there have been other incursions. In an eight-month period in 2012, over forty maritime incursions and 160 aerial incursions occurred.[83] For example, in July 2012, three Chinese patrol vessels entered the disputed waters around the islands.[84]

Military escalation continued in 2013. In February, Japanese Defense Minister Itsunori Onodera claimed that a Chinese frigate had locked weapons-targeting radar onto a Japanese destroyer and helicopter on two occasions in January.[85][86] A Chinese Jiangwei II class frigate and a Japanese destroyer were three kilometers apart, and the crew of the latter vessel went to battle stations.[87] The Chinese state media responded that their frigates had been engaged in routine training at the time.[88]

In May 2013, a flotilla of Chinese warships from its North Sea Fleet deployed from Qingdao for training exercises western North Pacific Ocean.[89] It is not known if this deployment is related to the ongoing islands dispute between China and Japan.[citation needed]

Other incidents

[edit]

On 22 July 2011, following its Vietnam port-call, the Indian amphibious assault vessel Airavat was reportedly contacted 45 nautical miles from the Vietnamese coast in the disputed South China Sea by a party identifying itself as the Chinese Navy and stating that the Indian warship was entering Chinese waters.[90][91] According to a spokesperson for the Indian Navy, since there were no Chinese ships or aircraft were visible, the INS Airavat proceeded on her onward journey as scheduled. The Indian Navy further clarified that "[t]here was no confrontation involving the INS Airavat. India supports freedom of navigation in international waters, including in the South China Sea, and the right of passage in accordance with accepted principles of international law. These principles should be respected by all."[90]

On 11 July 2012, the Chinese frigate Dongguan ran aground on Hasa Hasa Shoal (pictured) located 60 nmi west of Rizal, which was within the Philippines' 200 nmi-EEZ.[92] By 15 July, the frigate had been refloated and was returning to port with no injuries and only minor damage.[93] During this incident, the 2012 ASEAN summit took place in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, amid the rising regional tensions.[93]

2008 anti-piracy operations

[edit]On 18 December 2008, Chinese authorities deployed People's Liberation Army Navy vessels to escort Chinese shipping in the Gulf of Aden.[94] This deployment came after a series of attacks and attempted hijackings on Chinese vessels by Somali pirates. Reports suggest two destroyers (Type 052C 171 Haikou and Type 052B 169 Wuhan) and a supply ship are the ones being used.[citation needed]

This move was welcomed by the international community as the warships complement a multinational fleet already operating along the coast of Africa. Since this operation PLAN has sought the leadership of the ‘Shared Awareness and Deconfliction (SHADE)' body, which would require an increase in the number of ships contributing to the anti-piracy fleet. This is the first time Chinese warships have deployed outside the Asia-Pacific region for a military operation since Zheng He's expeditions in the 15th century.[citation needed]

Since then more than 30 People's Liberation Army Navy ships has deployed to the Gulf of Aden in 18 Escort Task Groups.

| Escort Task Group/Task Group | Sailors (including Navy and Marine or special forces personnel) |

Ships | Departure | Start | End | Return | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Escort Task Group/Task Group 169 | 869 | DDG-169 Wuhan (Type 052B destroyer), DDG-171 Haikou (Type 052C destroyer), AOR-887 Weishan Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 26 December 2008 | 26 January 2009 | 15 April 2009 | 28 April 2009 | [95][96] |

| 2nd Escort Task Group/Task Group 167 | 866 | DDG-167 Shenzhen (Type 051B destroyer), FFG-570 Huangshan (Type 054A frigate), AOR-887 Weishan Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 2 April 2009 | 15 April 2009 | 1 August 2009 | 21 August 2009 | [97] |

| 3rd Escort Task Group/Task Group 529 | 806 | FFG-529 Zhoushan (Type 054A frigate), FFG-530 Xuzhou (Type 054A frigate), AOR-886 Qiandao Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 16 July 2009 | 1 August 2009 | 29 November 2009 | 20 December 2009 | [98] |

| 4th Escort Task Group/Task Group 525 | 788 | FFG-525 Ma'anshan (Type 054 frigate), FFG-526 Wenzhou (Type 054 frigate), FFG-568 Chaohu (Type 054A frigate), AOG-886 Qiandao Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 30 October 2009 | 27 November 2009 | 18 March 2010 | 23 April 2010 | [99] |

| 5th Escort Task Group/Task Group 168 | 825 | DDG-168 Guangzhou (Type 052B destroyer), FFG-568 Chaohu (Type 054A frigate), AOR-887 Weishan Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 4 March 2010 (FFG-568 Chaohu on 2 December 2009) | 18 March 2010 (FFG-568 Chaohu on 21 December 2009) | 20 July 2010 | 12 September 2010 | [100] |

| 6th Escort Task Group/Task Group 998 | 981 | LPD-998 Kunlun Shan (Type 071 amphibious transport dock), DDG-171 Lanzhou (Type 052C destroyer), AOR-887 Weishan Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 30 June 2010 | 14 July 2010 | 20 November 2010 | 7 January 2011 | [101] |

| 7th Escort Task Group/Task Group 530 | 788 | FFG-529 Zhoushan (Type 054A frigate), FFG-530 Xuzhou (Type 054A frigate), AOR-886 Qiandao Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 2 November 2010 | 23 November 2010 | 11 November 2011 | 9 May 2011 | [102] |

| 8th Escort Task Group/Task Group 526 | 796 | FFG-525 Ma'anshan (Type 054 frigate), FFG-526 Wenzhou (Type 054 frigate), AOR-886 Qiandao Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 21 February 2011 | 18 March 2011 | 21 July 2011 | 28 August 2011 | [103] |

| 9th Escort Task Group/Task Group 169 | 878 | DDG-169 Wuhan (Type 052B destroyer), FFG-569 Yulin (Type 054A frigate), AOR-885 Qinghai Hu (Type 908 replenishment ship) | 2 July 2011 | 23 July 2011 | 15 November 2011 | 24 December 2011 | [104] |

| 10th Escort Task Group/Task Group 171 | 875 | DDG-171 Haikou (Type 052C destroyer), FFG-571 Yuncheng (Type 054A frigate), AOR-885 Qinghai Hu (Type 908 replenishment ship) | 2 November 2011 | 19 November 2011 | 17 March 2012 | 5 May 2012 | [105] |

| 11th Escort Task Group/Task Group 113 | 779 | DDG-113 Qingdao (Type 052 destroyer), FFG-538 Yantai (Type 054A frigate), AOR-887 Weishan Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 27 February 2012 | 17 March 2012 | 18 July 2012 | 12 September 2012 | [106] |

| 12th Escort Task Group/Task Group 548 | 788 | FFG-548 Yiyang (Type 054A frigate), FFG-549 Changzhou (Type 054A frigate), AOR-886 Qiandao Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 3 July 2012 | 18 July 2012 | 23 November 2012 | 19 January 2013 | [107] |

| 13th Escort Task Group/Task Group 570 | 787 | FFG-568 Hengyang (Ex-Chaohu, Type 054A frigate), FFG-570 Huangshan (Type 054A frigate), AOR-885 Qinghai Hu (Type 908 replenishment ship) | 9 November 2012 | 23 November 2012 | 13 March 2013 | 23 May 2013 | [108] |

| 14th Escort Task Group/Task Group 112 | 736 | DDG-112 Harbin (Type 052 destroyer), FFG-528 Mianyang (Type 053H3 frigate), AOR-887 Weishan Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 16 February 2013 | 13 March 2013 | 22 August 2013 (FFG-528 Mianyang on 25 August 2013) | 28 September 2013 | [109] |

| 15th Escort Task Group/Task Group 999 | 853 | LPD-999 Jinggang Shan (Type 071 amphibious transport dock), FFG-572 Hengshui (Type 054A frigate), AOR-889 Tai Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 8 August 2013 | 22 August 2013 | 20 December 2013 | 22 January 2014 | [110] |

| 16th Escort Task Group/Task Group 546 | 660 | FFG-527 Luoyang (Type 053H3 frigate), FFG-546 Yancheng (Type 054A frigate), AOR-889 Tai Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 11 November 2013 | 20 December 2013 | 18 April 2014 | 18 July 2014 | [111] |

| 17th Escort Task Group/Task Group 150 | 810 | DDG-150 Changchun (Type 052C destroyer), FFG-549 Changzhou (Type 054A frigate), AOR-890 Chao Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 25 March 2014 | 18 April 2014 | 23 August 2014 | 22 October 2014 | [112] |

| 18th Escort Task Group/Task Group 989 | 1200 | LPD-989 Changbai Shan (Type 071 amphibious transport dock), FFG-571 Yuncheng (Type 054A frigate), AOR-890 Chao Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 2 August 2014 | 23 August 2014 | 24 December 2014 | 19 March 2015 | [113] |

| 19th Escort Task Group/Task Group 547 | 780 | FFG-547 Linyi (Type 054A frigate), FFG-550 Weifang (Type 054A frigate), AOR-887 Weishan Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 2 December 2014 | 24 December 2014 | 24 April 2015 | 10 July 2015 | [114] |

| 20th Escort Task Group/Task Group 152 | ~800 | DDG-152 Jinan (Type 052C destroyer), FFG-528 Yiyang (Type 054A frigate), AOR-886 Qiandao Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 3 April 2015 | 24 April 2015 | 22 August 2015 | 5 February 2016 | [115] |

| 21st Escort Task Group/Task Group 573 | ~700 | FFG-573 Liuzhou (Type 054A frigate), FFG-574 Sanya (Type 054A frigate), AOR-885 Qinghai Hu (Type 908 replenishment ship) | 4 August 2015 | 22 August 2015 | 3 January 2016 | 8 March 2016 | [116] |

| 22nd Escort Task Group/Task Group 576 | ~700 | FFG-576 Daqing (Type 054A frigate), DDG-112 Harbin (Type 052 destroyer), AOR-889 Tai Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 6 December 2015 | 3 January 2016 | 29 April 2016 | 30 June 2016 | [117] |

| 23rd Escort Task Group/Task Group 531 | ~700 | FFG-531 Xiangtan (Type 054A frigate), FFG-529 Zhoushan (Type 054A frigate), AOR-890 Chao Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 7 April 2014 | 29 April 2016 | 4 September 2016 | 1 November 2016 | [118] |

| 24th Escort Task Group/Task Group 112 | ~700 | DDG-112 Harbin (Type 052 destroyer), FFG-579 Handan (Type 054A frigate), AOR-960 Dongping Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 10 August 2014 | 2 September 2016 | 5 January 2017 | 8 March 2017 | [119] |

| 25th Escort Task Group/Task Group 568 | ~700 | FFG-568 Hengyang (Type 054A frigate), FFG-569 Yulin (Type 054A frigate), AOR-963 Hong Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 17 December 2016 | 2 January 2017 | 21 April 2017 | 12 July 2017 | [120] |

| 26th Escort Task Group/Task Group 577 | ~700 | FFG-577 Huanggang (Type 054A frigate), FFG-578 Yangzhou (Type 054A frigate), AOR-966 Gaoyou Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 1 April 2017 | 21 April 2017 | 23 August 2017 | 1 December 2017 | [121] |

| 27th Escort Task Group/Task Group 171 | ~700 | DDG-171 Haikou (Type 052C destroyer), FFG-575 Yueyang (Type 054A frigate), AOR-885 Qinghai Hu (Type 908 replenishment ship) | 1 August 2017 | 23 August 2017 | 26 December 2017 | 18 March 2018 | [122] |

| 28th Escort Task Group/Task Group 546 | ~700 | FFG-546 Yancheng (Type 054A frigate), FFG-550 Weifang (Type 054A frigate), AOR-889 Tai Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 3 December 2017 | 26 December 2017 | 1 May 2018 | 9 August 2018 | [123] |

| 29th Escort Task Group/Task Group 515 | ~700 | FFG-515 Binzhou (Type 054A frigate), FFG-530 Xuzhou (Type 054A frigate), AOR-886 Qiandao Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 4 April 2018 | 28 April 2018 | 3 September 2018 | 4 October 2018 | [124] |

| 30th Escort Task Group/Task Group 539 | ~700 | FFG-539 Wuhu (Type 054A frigate), FFG-579 Handan (Type 054A frigate), AOR-960 Dongping Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 6 August 2018 | 1 September 2018 | 24 December 2018 | 27 January 2019 | [125] |

| 31st Escort Task Group/Task Group 998 | ~700 | LPD-998 Kunlun Shan (Type 071 amphibious transport dock), FFG-536 Xuchang (Type 054A frigate), AOR-964 Luoma Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 9 December 2018 | 24 December 2018 | 28 April 2019 | 30 May 2019 | [126][127] |

| 32nd Escort Task Group/Task Group 153 | ~700 | DDG-153 Xi'an (Type 052C destroyer), FFG-599 Anyang (Type 054A frigate), AOR-966 Gaoyou Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 4 April 2019 | 28 April 2019 | 14 September 2019 | 1 November 2019 | [126][128] |

| 33rd Escort Task Group/Task Group 117 | ~600 | DDG-117 Xining (Type 052D destroyer), FFG-550 Weifang (Type 054A frigate), AOR-968 Hoh Xil Hu (Type 903A replenishment ship) | 29 August 2019 | 14 September 2019 | 20 November 2019 | 1 January 2020 | [128] |

| 34th Escort Task Group/Task Group 118 | ~700 | DDG-117 Xining (Type 052D destroyer), FFG-550 Weifang (Type 054A frigate), AOR-887 Weishan Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 10 June 2020 | 14 July 2019 | 14 March 2020 | 10 April 2020 | |

| 35th Escort Task Group/Task Group 122 | ~600 | DDG-131 Taiyuan (Type 052D destroyer), FFG-532 Jingzhou (Type 054A frigate), AOR-890 Chao Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 28 April 2020 | 14 May 2020 | 1 August 2020 | 14 October 2020 | |

| 36th Escort Task Group/Task Group 202 | ~700 | DDG-119 Guiyang (Type 052D destroyer), FFG-542 Zaozhuang (Type 054A frigate), AOR-960 Dongping Hu (Type 903 replenishment ship) | 4 September 2020 | 14 October 2020 | Ongoing | Ongoing |

2011 Libyan Civil War

[edit]In the lead-up to the 2011 Libyan Civil War, the Xuzhou (530) was deployed from anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden to help evacuate Chinese nationals from Libya.[129]

Yemen conflict

[edit]During the Yemen conflict, in 2015, the Chinese Navy diverted frigates carrying out anti-piracy operations in Somalia to evacuate at least 600 Chinese and 225 foreign citizens working in Yemen. Among the non-Chinese evacuees were 176 Pakistani citizens, with smaller numbers from other countries, such as Ethiopia, Singapore, the UK, Italy, and Germany. Despite the evacuations, the Chinese embassy in Yemen continued to operate.[130]

Ream Naval Base

[edit]Equipment

[edit]

China's navy is the second-largest in the world in terms of tonnage.[30]: 263

As of 2018, the Chinese navy operates over 496 combat ships and 232 various auxiliary vessels and counts 255,000 seamen in its ranks. The Chinese Navy also employ more than 710 naval aircraft, including fighters, bombers and electronic warfare aircraft. China has large amount of artillery, torpedoes, and missiles included in their combat assets.[citation needed]

As of 2024[update] China has the capacity to build more ships in one month than the United States builds in a year, with commercial vessels being built alongside warships and constructed to include military specifications.[137] Experts have compared the country's grip on the shipping industry as similar to Japan's in the mid-1900s.[138]

Ships and submarines

[edit]As of 2024, the navy has an overall battle force of more than 350 ships and submarines.[30]: 263–264

All ships and submarines currently in commission with the People's Liberation Army Navy were built in China, with the exception of the Sovremenny-class destroyers, Kilo-class submarines and the aircraft carrier Liaoning. Those vessels were either imported from or originated in Russia.

China employs a wide range of Navy combatants including aircraft carriers, amphibious warfare ships, and destroyers. The Chinese Navy is undergoing modernization rapidly with nearly half of Chinese Navy combat ships built after 2010. China's state-owned shipyards have built 83 ships in just eight years with unprecedented speed. China has its own independent maritime missile defense and naval combat system similar to US Aegis.[139]

Aircraft

[edit]China operates carrier-based fighter aircraft to secure land, air and sea targets. The Chinese Navy also operates a wide range of helicopters for battlefield logistics, reconnaissance, patrol and medical evacuation.

Naval weaponry

[edit]The unique QBS-06 is an underwater assault rifle with 5.8×42 DBS-06, and is used by Naval frogmen.[140] It is based on the Soviet APS.[141]

In early February 2018, pictures of what is claimed to be a Chinese railgun were published online. In pictures the gun is shown mounted on the bow of a Type 072III-class landing ship Haiyangshan. Media is suggesting that the system is or soon will be ready for testing.[142][143] In March 2018, it was reported that China had confirmed that it had begun testing its electromagnetic rail gun at sea.[144][145]

Future of the People's Liberation Army Navy

[edit]

The PLAN's ambitions include operating out to the first and second island chains, as far as the South Pacific near Australia, and spanning to the Aleutian islands, and operations extending to the Straits of Malacca near the Indian Ocean.[146] The future PLAN fleet will be composed of a balance of combatant assets aimed at maximising the PLAN's fighting effectiveness.[147]

On the high end, there would be modern destroyers, such as stealth guided missile destroyers equipped with long-range air defense missiles and anti-submarine capabilities (Type 055). There would be modern destroyers equipped with long-range air defense missiles (Type 052B, Type 052C, Type 052D and Type 051C, and destroyers armed with supersonic anti-ship missiles (Sovremenny class).[147]

There would be advanced nuclear-powered attack and ballistic missile submarines (Type 093, Type 095, Type 094, Type 096), advanced conventional attack submarines (Kilo and Yuan classes), aircraft carriers (Type 001, Type 002 and Type 003), and helicopter carriers (Type 075) and large amphibious warfare vessels (Type 071) capable of mobilizing troops at long distances.[147]

On the medium and low end, there would be more economical multi-role capable frigates and destroyers (Luhu, Jiangwei II and Jiangkai classes), corvettes (Jiangdao class), fast littoral missile attack craft (Houjian, Houxin and Houbei classes), various landing ships and light craft, and conventionally powered coastal patrol submarines (Song class). The obsolete combat ships (based on 1960s designs) will be phased out in the coming decades as more modern designs enter full production.[147]

Between 2001 and 2006 there was a rapid building and acquisition program,[146] a trend which continued. There were more than a dozen new classes of ships built in those five years,[146] totaling some 60 brand new ships (including landing ships and auxiliaries).[146] Simultaneously, dozens of other ships have been either phased out of service or refitted with new equipment.

Submarines play a significant role in the development of the PLAN's future fleet. This is made evident by the construction of a new type of nuclear ballistic missile submarine, the Type 094 and the Type 093 nuclear attack submarine. This will provide the PLAN with a more modern response for the need of a seaborne nuclear deterrent. The new submarines will also be capable of performing conventional strike and other special warfare requirements.[citation needed]

Ronald O'Rourke of the Congressional Research Service reported that the long-term goals of PLAN planning include:

- Assert or defend China's claims in maritime territorial disputes and China's interpretation of international laws relating to freedom of navigation in exclusive economic zones (an interpretation at odds with the U.S. interpretation);

- Protect China's sea lines of communications to the Persian Gulf, on which China relies for some of its energy imports.[148]

During the military parade on the 60th anniversary of the People's Republic of China, the YJ-62 naval cruise missile made its first public appearance; the YJ-62 represents the next generation in naval weapons technology in the PLA.[citation needed]

Following the construction of its two smaller aircraft carriers, China began building the improved Type 003 carrier, which is expected to displace 83,000 tonnes and enable CATOBAR operations by 2022.[149]

The PLAN may also operate from Gwadar or Seychelles for anti-piracy missions and to protect vital trade routes which may endanger China's energy security in the case of a conflict. In 2016, China established her first overseas naval base in Djibouti, which provided necessary support for Chinese fleet and troops.

As of 2017[update], China reportedly began testing designs for arsenal ships.[150]

The Pentagon's name for the Chinese sea based militia is the People's Armed Forces Maritime Militia. Their future role is unknown, but war planners have been aware of their history and potential use in naval conflict.[151]

As of 2024[update], China's shipbuilding workforce services over 7,000 vessels and is estimated to be nearly five times that of the United States.[137]

See also

[edit]- Chinese aircraft carrier programme

- China Coast Guard

- Dalian Naval Academy

- List of ships of the People's Liberation Army Navy

- People's Liberation Army Navy Band

- Political Commissar of the People's Liberation Army Navy

- Political Department of the People's Liberation Army Navy

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "The PLA Oath" (PDF). February 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

I am a member of the People's Liberation Army. I promise that I will follow the leadership of the Communist Party of China...

- ^ International Institute for Strategic Studies 2024, p. 256.

- ^ International Institute for Strategic Studies 2024, p. 257-258.

- ^ International Institute for Strategic Studies 2024, p. 258.

- ^ International Institute for Strategic Studies 2024, p. 256-260.

- ^ a b "中国人民解放军海军成立70周年多国海军活动新闻发布会在青岛举行". mod.gov.cn (in Chinese). Ministry of National Defence of the People's Republic of China. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ "China to conduct naval drills in Pacific amid tension". Reuters. 30 January 2013.

- ^ Ronald O'Rourke, "China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities – Background and Issues for Congress", 10 December 2012, p. 7

- ^ "Indonesia bolsters navy as China steps up incursions around ASEAN".

- ^ "Japanese Submarines to Counter Chinese Navy Incursions". Forbes.

- ^ "China says its carrier group exercising near Taiwan, drills will become regular". Reuters. 6 April 2021.

- ^ "What is nine-dash line? The basis of China's claim to sovereignty over South China Sea". Theprint.in. 28 July 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "The Dispute Over the South China Sea" (PDF). Constitutional Rights Foundation. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ Gordon, Michael R.; Youssef, Nancy A. (6 August 2023). "WSJ News Exclusive | Russia and China Sent Large Naval Patrol Near Alaska". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ "Japan protests Chinese navy ship entering Japanese waters". Reuters. 8 June 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ Ogura, Brad Lendon,Junko (12 May 2023). "Chinese warships sail around Japan as tensions rise ahead of G7 summit". CNN. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "China says Taiwan encirclement drills a 'serious warning'". AP News. 12 April 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ "Global Naval Powers Ranking (2024)". World Directory of Modern Military Warships. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ a b Axe, David (5 November 2021). "Yes, China Has More Warships Than The USA. That's Because Chinese Ships Are Small". Forbes. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ Lendon, Brad (17 January 2023). "Expert's warning to US Navy on China: Bigger fleet almost always wins". CNN. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ "The state of the U.S. Navy as China builds up its naval force and threatens Taiwan". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ "2024 China Military Power Report". Media.defense.gov.

- ^ "Naval Vessel Register". nvr.navy.mil/.

- ^ Palmer, Alexander; Carroll, Henry H.; Velazquez, Nicholas (5 June 2024). "Unpacking China's Naval Buildup". Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ Adams, Cathalijne (18 September 2023). "China's Shipbuilding Capacity is 232 Times Greater Than That of the United States". Alliance for American Manufacturing. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ Trevithick, Joseph (11 July 2023). "Alarming Navy Intel Slide Warns Of China's 200 Times Greater Shipbuilding Capacity". The War Zone. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ Tangredi, Sam J. (January 2023). "Bigger Fleets Win". Proceedings. Vol. 149/1/1439. United States Naval Institute. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Cole, Bernard D. The Great Wall at Sea Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2001

- ^ a b c d Li, Xiaobing (2024). "Beijing's Military Power and East Asian-Pacific Hot Spots". In Fang, Qiang; Li, Xiaobing (eds.). China under Xi Jinping: A New Assessment. Leiden University Press. ISBN 9789087284411.

- ^ Dengfeng, Wu (2009). "Deep Blue Defense – A Modern Force at Sea". Focus. China Pictorial. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ Dumbaugh, Kerry; Richard Cronin; Shirley Kan; Larry Niksch; David M. Ackerman (2 February 2009) [12 November 2001]. China's Maritime Territorial Claims: Implications for U.S. Interests (PDF). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service (CRS). pp. CRS–32. OCLC 48670022. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ Kim, Duk-ki (2000). Naval strategy in Northeast Asia: geo-strategic goals, policies, and prospects. New York City: Routledge. p. 152. ISBN 0-7146-4966-X. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ Graham, Euan (2005). Japan's sea lane security, 1940–2004: a matter of life and death?. New York: Institute/Routledge Japanese Studies. p. 208. ISBN 0-415-35640-7.

- ^ "2002: Chinese naval ships made first round -the-world sailing". Yearly Focus. PLA Daily. 8 October 2008. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ "Chinese Naval Fleet Concludes Visit to Turkey". World News. People's Daily Online. 24 June 2002. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ^ "China to add special forces, helicopters to fight pirates". Shanghai Daily. 23 December 2008. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ^ "China ready to use force on Somali pirates". Defencetalk.com. 23 December 2008. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ^ Erikson, Andrew R.; Mikolay, Justine D. (March 2009). "Welcome China to the Fight Against Pirates". U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings. 135 (3): 34–41. ISSN 0041-798X. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

Access requires registration.

- ^ a b Hille, Kathrin (24 April 2009). "China's show of sea power challenges US". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Niu, Guang (23 April 2009). "The Chinese Navy missile destroyer 116 Shijiazhuang (3rd L),..." Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Axe, David. "China's Overhyped Sub Threat". Medium. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ "Chinese warships visit Penang – Community | The Star Online". www.thestar.com.my. 13 May 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ Chan, Minnie (3 July 2013). "China to join Russia in joint naval drills in Sea of Japan". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2 July 2013.; and "China to join Russia in Beijing's largest-ever joint naval exercise with foreign partner". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 2 July 2013. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ "China-led evacuation from war-torn Yemen said to include Canadians". CBC News. 3 April 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ^ Stewart, Phil (22 March 2013). "China to attend major U.S.-hosted naval exercises, but role limited". Reuters.

- ^ "China confirms attendance at U.S.-hosted naval exercises in June". Reuters. 9 June 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ Tiezzi, Shannon (11 June 2014). "A 'Historic Moment': China's Ships Head to RIMPAC 2014". The Diplomat. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ Eckstein, Megan (18 April 2016). "SECDEF Carter: China Still Invited to RIMPAC 2016 Despite South China Sea Tension". USNI News. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023.

- ^ F_161. "Expert: One Chinese aircraft carrier insufficient to cope with high-intensity combat – People's Daily Online". Retrieved 25 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Shinn, David H.; Eisenman, Joshua (2023). China's Relations with Africa: a New Era of Strategic Engagement. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-21001-0.

- ^ Sutton, H. I. (17 December 2020). "Beijing Upgrading Naval Bases To Strengthen Grip On South China Sea". Naval News. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ "China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress". Congressional Research Service: 2.

- ^ Easton, Ian (31 January 2014). "China's Deceptively Weak (and Dangerous) Military". thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ Hanson, Capt. Michael A. (April 2020). "China's Marine Corps Is on the Rise". U.S. Naval Institute. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "China's first aircraft carrier enters service". Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ a b Ping, Xu (7 August 2017). "我军建军九十年军衔制度沿革" [The evolution of our military rank system over the ninety years of its establishment]. mod.gov.cn (in Chinese). Ministry of National Defense. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ "China's Arrival: A Strategic Framework for a Global Relationship, page 50" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ "Secret Sanya – China's new nuclear naval base revealed – Jane's Security News". Janes.com. 21 April 2008. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ Harding, Thomas, "Chinese Build Secret Nuclear Submarine Base", The Daily Telegraph (London), 2 May 2008.

- ^ Harding, Thomas, "Chinese Nuclear Submarines Prompt 'New Cold War' Warning", The Daily Telegraph (London), 3 May 2008.

- ^ a b "China has aircraft carrier hopes". BBC News. 17 November 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "China's 'aggressive' buildup called worry". The Washington Times. 14 January 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ "US Reaffirms Its Rights to Operate in South China Sea". Voanews.com. 16 July 2009. Archived from the original on 17 August 2009. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ Ronald O’Rourke (23 December 2009). "CRS RL33153 China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities–Background and Issues for Congress". Congressional Research Service. Archived from the original on 18 February 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ Chang, Felix K. (October 2012). "Making Waves: Debates Behind China's First Aircraft Carrier" (PDF). Foreign Policy Research Institute. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Perlez, Jane (25 September 2012). "China Launches Carrier, but Experts Doubt Its Worth". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ "Janes | Latest defence and security news". Janes.com. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "China sea power concerns new Japan foreign minister". Japan Today. 3 September 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Tangredi, Sam (August 2017). "Fight Fire with Fire". U.S. Naval Institute's Proceedings Magazine.

- ^ Lendon, Brad (28 June 2017). "China's newest destroyer seen as challenge to Asia rivals". CNN. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ "2020 China Military Power Report" (PDF). Media.defense.gov.

- ^ Patton, Keith (24 April 2019). "Battle Force Missiles: The Measure of a Fleet". Center for International Maritime Security. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ a b Alan Cummings. "A THOUSAND SPLENDID GUNS: Chinese ASCMs in Competitive Control". Naval War College Review. 69 (4): 82–84.

- ^ Jamandre, Tessa (3 June 2011). "China fired at Filipino fishermen in Jackson atoll". ABS-CBN. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ^ Gertz, Bill (8 August 2012). "Inside the Ring: China warship grounded". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on 11 August 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ^ Ogura, Junko (14 October 2010). "Japanese party urges Google to drop Chinese name for disputed islands". CNN World. US. CNN. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012.

- ^ Kristof, Nicholas (10 September 2010). "Look Out for the Diaoyu Islands". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ John W. Finney (11 November 1971). "Senate Endorses Okinawa Treaty – Votes 84 to 6 for Island's Return to Japan – Rioters There Kill a Policeman Senate, in 84 to 6 Vote, Approves the Treaty Returning Okinawa to Japan – Front Page". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ Netherlands Institute for the Law of the Sea (NILOS). (2000). International Organizations and the Law of the Sea, pp. 107–108., p. 107, at Google Books

- ^ Lee, Seokwoo et al. (2002). Territorial disputes among Japan, Taiwan and China concerning the Senkaku Islands, pp. 11–12., p. 11, at Google Books

- ^ "Q&A: China-Japan islands row" BBC News 11 September 2012

- ^ Richard D. Fisher Jr. (25 February 2013). "Japan Will Have Busy Year Defending Islands Against China". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

Between March and November, 47 Chinese ship incursions were recorded. From April to December, the Japanese Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF) scrambled fighters 160 times in response to Chinese aircraft in the East China Sea, up from 156 in 2011.

- ^ "Chinese ships near disputed islands: Japan". 11 July 2012. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013.

- ^ Herman, Steve. "Japan Protests Chinese Ship's Alleged Use of Radar to Guide Missiles". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ Yamaguchi, Mari (5 February 2013). "Japan Accuses China of Using Weapons Radar on Ship". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ Eric S Margolis (11 February 2013). "Stopping short of war". The Nation. Nawaiwaqt Group of Newspapers. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ Mingxin, Bi (8 February 2013). "China refutes Japan's allegations on radar targeting". Xinhua. Xinhua Network Corporation Limited. Archived from the original on 11 February 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

Buckley, Chris (8 February 2013). "China Denies Directing Radar at Japanese Naval Vessel and Copter". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 March 2013. - ^ "PLA Navy's three fleets meet in South China Sea for rare show of force". South China Morning Post. 24 June 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ a b "China face-off in South China Sea" DNA India report

- ^ "Southasiaanalysis.org". Southasiaanalysis.org. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Laude, Jamie. "China ship runs aground near Phl" The Philippine Star. 14 July 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Stranded naval frigate refloated." AFP. 15 July 2012

- ^ "Somalia Pirates: China Deploys Navy To Gulf of Aden Following Hijack Attempt | World News | Sky News". News.sky.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ Sun, Yanxin; Zhu, Hongliang (28 April 2009). "海军首批护航编队圆满完成护航任务顺利返回三亚" [Navy's First Escort Task Group completed mission and returned to Sanya]. Xinhua. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第一批护航编队" [1st Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第二批护航编队" [2nd Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第三批护航编队" [3rd Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第四批护航编队" [4th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第五批护航编队" [5th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第六批护航编队" [6th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第七批护航编队" [7th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第八批护航编队" [8th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第九批护航编队" [9th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第十批护航编队" [10th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第十一批护航编队" [11th Escort Task Group]. PLA Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第十二批护航编队" [12th Escort Task Group]. PLA Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第十三批护航编队" [13th Escort Task Group]. PLA Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第十四批护航编队" [14th Escort Task Group]. PLA Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第十五批护航编队" [15th Escort Task Group]. PLA Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第十六批护航编队" [16th Escort Task Group]. PLA Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第十七批护航编队" [17th Escort Task Group]. PLA Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第十八批护航编队" [18th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第十九批护航编队" [19th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第二十批护航编队" [20th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第二十一批护航编队" [21st Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第二十二批护航编队" [22nd Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第二十三批护航编队" [23rd Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第二十四批护航编队" [24th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第二十五批护航编队" [25th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第二十六批护航编队" [26th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第二十七批护航编队" [27th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第二十八批护航编队" [28th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第二十九批护航编队" [29th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第三十批护航编队" [30th Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ a b Xue, Chengqing; Gu, Yagen (28 April 2019). Sun, Zhiying (ed.). "我海军第31批与第32批护航编队顺利会合" [PLAN 31st and 32nd Escort Task Group Successfully Rendezvoused]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Liu, Qiuli, ed. (14 December 2018). "第三十一批护航编队" [31st Escort Task Group]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ a b Lin, Jian; Li, Hao (17 September 2019). Liu, Qiuli (ed.). "第三十二、三十三批护航编队在亚丁湾会合" [32nd and 33rd Escort Task Group Rendezvoused at Golf of Aden]. People's Liberation Army Daily. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ "Chinese navy frigate crosses Suez Canal for Libya evacuation". Xinhua. 28 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ "Yemen battle prompts Chinese rescue". BBC News. 3 April 2015.

- ^ "China secretly building PLA naval facility in Cambodia, Western officials say". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Hutt, David (22 July 2019). "Cambodia, China ink secret naval port deal: report". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ Sun Narin (3 June 2021), "Defense Minister Says China Helping with Ream Overhaul, But 'No Strings Attached", Voice of America, archived from the original on 4 August 2022, retrieved 22 January 2022

- ^ a b Africk, Brady (7 October 2024). "China is rapidly building warships. Satellite images reveal the scale". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ Ang, Irene (5 November 2024). "How China has taken a generational grip on the global shipbuilding industry". TradeWinds | Latest shipping and maritime news. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ "High-speed production: Chinese navy built 83 ships in just eight years". The print. 20 September 2017.

- ^ "QBS-06 underwater assault rifle (PR China)". 4 June 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ "国产QBS06式5.8毫米水下自动步枪猜想". Xilu.com. 6 April 2011. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ "What is a hypersonic railgun? How the superweapon China may be building works". Newsweek. 2 February 2018. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ "Is China Getting Ready to Test a Railgun?". February 2018. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ "China Says It Is Testing World's First Railgun at Sea, Confirming Leaked Photos of Electromagnetic Weapon". Newsweek. 14 March 2018.

- ^ "China's Railgun Confirmed: Military 'Award' Reveals Electromagnetic Supergun Tested at Sea". News Corp Australia. 15 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d Annual Report to Congress, Military Power of the People's Republic of China. Retrieved 22 May 2008

- ^ a b c d "The Next Arms Race". Apac2020.the-diplomat.com. 14 January 2010. Archived from the original on 18 August 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ "China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress". Opencrs.com. Archived from the original on 14 October 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ Funaiole, Matthew P.; Jr, Joseph S. Bermudez (14 July 2021). "Progress Report on China's Type 003 Carrier". www.csis.org. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Lin, Jeffrey; Singer, P.W. (1 June 2017). "China is developing a warship of naval theorists' dreams". Popular Science.

- ^ Peter Dobbie and Al Jazeera reporters. (1 May 2021). "Video: How China came to dominate the South China Sea". Al Jazeera English website Retrieved 2 May 2021.

Sources

[edit]- International Institute for Strategic Studies (February 2024). The Military Balance 2024. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781032780047.