Navajo water rights

Water rights for the Navajo Nation have been a source of environmental conflict for decades, as Navajo lands have provided energy and water for residents of neighboring states while many of the Navajo do not have electricity or running water in their homes. Beginning in the 1960s, coal mining by Peabody coal at Black Mesa withdrew more than 3 million gallons of water/day from the Navajo aquifer, reducing the number of springs on the reservation. The Navajo Generating Station also consumed about 11 billion gallons of water per year to provide power for the Central Arizona Project that pumps water from Lake Havasu into Arizona.

Native American tribes along the Colorado River were left out of the 1922 Colorado River Compact that divided water among the states, forcing tribes to negotiate settlements with the states for water. The Navajo negotiated water settlements with New Mexico and Utah in 2009 and 2020 respectively, but had not reached an agreement with Arizona in 2023.

On June 22, 2023, the US Supreme Court ruled in Arizona v. Navajo Nation that the federal government of the United States has no obligation to ensure that the Navajo Nation has access to water. The court ruled that the 1868 treaty establishing the Navajo Reservation reserved necessary water to accomplish the purpose of the Navajo Reservation but did not require the United States to take affirmative steps to secure water for the Tribe.[1]

Additionally, environmental crises, such as the 2015 Gold King Mine waste water spill have had lasting impact on the Nation's access to clean water.[2]

Water rights and access

[edit]The Navajo reservation is the largest Indian reservation in the US with a population of about 175,000 people. In 2023, about one third of residents did not have running water in their homes.[3]

Water rights to the Colorado River are governed by the 1922 Colorado River Compact that divides the water among western states. Indigenous Nations were left out of this agreement, forcing them to negotiate for water from the states.[4][5] In 1908, the US Supreme Court ruled in Winters vs United States that Native American water rights should have priority over settler claims, because the federal government established those claims when the reservations were formed.[6][7]

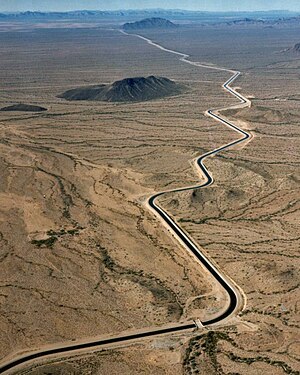

Beginning in the 1960s, coal mining by Peabody coal at Black Mesa withdrew more than 3 million gallons of water/day from the Navajo aquifer, reducing the number of springs on the reservation.[8] From 1968 until 2019, the Navajo Generating Station consumed 11 billion gallons of water/year to provide power for the Central Arizona Project, which pumps water from Lake Havasu into Arizona.[9]

In 2005, the tribe made a water agreement with the state of New Mexico securing some water rights in the San Juan Basin. Congress approved that agreement in 2009, but the tribe lacked pipeline infrastructure to access that water.[10] The San Juan Generating Station’s water reservoir was sold to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in 2023 to provide a reliable and sustainable water supply to Navajo homes and businesses. The reservoir was renamed the Frank Chee Willetto Reservoir.[11]

In 2020, the tribe completed a water settlement with the state of Utah.[12]

In 2023, the tribe still had not completed a settlement with the state of Arizona, and is not receiving their share of Arizona's water under the Colorado River Compact.[13] Arizona has tried to use water access as a way to force the Navajo to make concessions on unrelated issues, and other tribes have also had trouble negotiating water settlements with Arizona.[14]

Arizona v Navajo Nation

[edit]The tribe brought a lawsuit against the federal government in 2003, seeking to force the federal government to assess the Nation's water needs and "devise a plan to meet those needs."[1] The states of Nevada, Arizona, and Colorado intervened in the suit to protect their access to water from the Colorado River.[1]

In 2021, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the tribe could force the government to ensure its access to water.[15]

The suit was decided by the Supreme Court in 2023 in favor of the states. Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote the majority opinion, and said that the 1868 Treaty of Bosque Redondo between the Navajo Nation and the federal government did not require that the US government secure water access for the Navajo.[16]

Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote the dissenting opinion, and argued that the federal government should identify the water rights that are held for the Navajo Nation and ensure that water had not been misappropriated.[1]

The court affirmed the Navajo Nation's right to intervene in lawsuits related to water claims.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Liptak, Adam (2023-06-22). "Supreme Court Rules Against Navajo Nation in Water Rights Case". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-06-24.

- ^ "Navajo Crops Drying Out as San Juan River Remains Closed After Toxic Spill". indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- ^ "Supreme Court rules against Navajo Nation in Colorado River water rights case". AP NEWS. 2023-06-22. Retrieved 2023-06-24.

- ^ Denetclaw, Pauly (2022-03-01). "Tribes along the Colorado River navigate a stacked settlement process to claim their water rights". High Country News. Retrieved 2023-06-25.

- ^ Denetclaw, Pauly (2022-03-10). "Tribes along the Colorado River navigate a stacked settlement process to claim their water rights". Arizona Mirror. Retrieved 2023-10-02.

- ^ Shea, Parker (2019-11-08). "Navajo Generating Station closure leaves questions of water ownership". Arizona Mirror. Retrieved 2023-10-02.

- ^ MacGregor (2020). "When the Navajo Generating Station Closes, Where Does the Water Go?" (PDF). Colorado Natural Resources Energy and Environmental Review.

- ^ Kutz, Jessica (2021-02-01). "The fight for an equitable energy economy for the Navajo Nation". www.hcn.org. Retrieved 2023-10-02.

- ^ Shea, Parker (2019-11-08). "Navajo Generating Station closure leaves questions of water ownership". Arizona Mirror. Retrieved 2023-10-02.

- ^ Walton, Brett (2010-11-10). "Navajo Nation Council Approves Water Rights Settlement". Circle of Blue. Retrieved 2023-06-24.

- ^ Segarra, Curtis (2023-07-20). "After decades of use in a coal power plant, a New Mexico reservoir will help bring water to the Navajo Nation". KRQE News 13. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "'A 100-year tragedy' for tribes in the Colorado River Basin". Deseret News. 2022-12-20. Retrieved 2023-10-02.

- ^ Smith, Anna V.; Blaeser, Jessie (2022-11-16). "Tribal nations fight for influence on the Colorado River". High Country News. Retrieved 2023-06-25.

- ^ Smith, Anna V.; Olalde, Mark (2023-06-14). "How Arizona squeezes tribes for water". www.hcn.org. Retrieved 2023-10-02.

- ^ "Supreme Court rules against Navajo Nation in water rights dispute". NBC News. 2023-06-22. Retrieved 2023-06-24.

- ^ a b Barnes, Robert (June 22, 2023). "Supreme Court rules against Navajo Nation request for water rights". Washington Post.