Slug

| Slug | |

|---|---|

| |

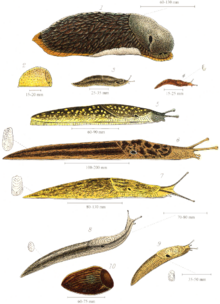

| Various species of British land slugs, including (from the top) the larger drawings: Arion ater, Kerry slug, Limax maximus and Limax flavus | |

| |

| Arion sp., from Vancouver, BC | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Groups included | |

| |

Slug, or land slug, is a common name for any apparently shell-less terrestrial gastropod mollusc. The word slug is also often used as part of the common name of any gastropod mollusc that has no shell, a very reduced shell, or only a small internal shell, particularly sea slugs and semi-slugs (this is in contrast to the common name snail, which applies to gastropods that have a coiled shell large enough that they can fully retract their soft parts into it).

Various taxonomic families of land slugs form part of several quite different evolutionary lineages, which also include snails. Thus, the various families of slugs are not closely related, despite the superficial similarity in overall body form. The shell-less condition has arisen many times independently as an example of convergent evolution, and thus the category "slug" is polyphyletic.

Taxonomy

[edit]Of the six orders of Pulmonata, two – the Onchidiacea and Soleolifera – solely comprise slugs. A third group, the Sigmurethra, contains various clades of snails, semi-slugs (i.e. snails whose shells are too small for them to retract fully into), and slugs.[1] The taxonomy of this group is in the process of being revised in light of DNA sequencing.[2] Research suggests that pulmonates are paraphyletic and basal to the opisthobranchs, which are a terminal branch of the tree.[3] The family Ellobiidae are also polyphyletic.

- Subinfraorder Orthurethra

- Superfamily Achatinelloidea Gulick, 1873

- Superfamily Cochlicopoidea Pilsbry, 1900

- Superfamily Partuloidea Pilsbry, 1900

- Superfamily Pupilloidea Turton, 1831

- Subinfraorder Sigmurethra

- Superfamily Acavoidea Pilsbry, 1895

- Superfamily Achatinoidea Swainson, 1840

- Superfamily Aillyoidea Baker, 1960

- Superfamily Arionoidea J.E. Gray in Turnton, 1840

- Superfamily Athoracophoroidea

- Family Athoracophoridae

- Superfamily Orthalicoidea

- Subfamily Bulimulinae

- Superfamily Camaenoidea Pilsbry, 1895

- Superfamily Clausilioidea Mörch, 1864

- Superfamily Dyakioidea Gude & Woodward, 1921

- Superfamily Gastrodontoidea Tryon, 1866

- Superfamily Helicoidea Rafinesque, 1815

- Superfamily Helixarionoidea Bourguignat, 1877

- Superfamily Limacoidea Rafinesque, 1815

- Superfamily Oleacinoidea H. & A. Adams, 1855

- Superfamily Orthalicoidea Albers-Martens, 1860

- Superfamily Plectopylidoidea Moellendorf, 1900

- Superfamily Polygyroidea Pilsbry, 1894

- Superfamily Punctoidea Morse, 1864

- Superfamily Rhytidoidea Pilsbry, 1893

- Family Rhytididae

- Superfamily Sagdidoidera Pilsbry, 1895

- Superfamily Staffordioidea Thiele, 1931

- Superfamily Streptaxoidea J.E. Gray, 1806

- Superfamily Strophocheiloidea Thiele, 1926

- Superfamily Parmacelloidea

- Superfamily Zonitoidea Mörch, 1864

- Superfamily Quijotoidea Jesús Ortea and Juan José Bacallado, 2016

- Family Quijotidae

Description

[edit]

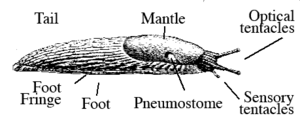

The external anatomy of a slug includes the following:

- Tentacles: Like other pulmonate land gastropods, the majority of land slugs have two pairs of 'feelers' or tentacles on their head. The upper pair is light-sensing and has eyespots at the ends, while the lower pair provides the sense of smell. Both pairs are retractable in stylommatophoran slugs, but contractile in veronicellid slugs.

- Mantle: On top of the slug, behind the head, is the saddle-shaped mantle. In stylommatophoran slugs, on the right-hand side of the mantle is a respiratory opening, the pneumostome, which is easier to see when open; also on the right side at the front are the genital opening and anus. Veronicellid slugs have a mantle covering the whole dorsal part of the body, they have no respiratory opening, and the anus opens posteriorly.

- Tail: The part of a slug behind the mantle is called the 'tail'.

- Keel: Some species of slugs, for example Tandonia budapestensis, have a prominent ridge running over their back along the middle of the tail (sometimes along the whole tail, sometimes only the posterior part).

- Foot: The bottom side of a slug, which is flat, is called the 'foot'. Like almost all gastropods, a slug moves by rhythmic waves of muscular contraction on the underside of its foot. It simultaneously secretes a layer of mucus that it travels on, which helps prevent damage to the foot tissues.[4] Around the edge of the foot in some slugs is a structure called the 'foot fringe'.

- Vestigial shell: Most slugs retain a remnant of their shell, which is usually internalized. This organ generally serves as storage for calcium salts, often in conjunction with the digestive glands.[5] An internal shell is present in the Limacidae[6] and Parmacellidae.[7] Adult Philomycidae,[6] Onchidiidae[8] and Veronicellidae[9] lack shells.

Physiology

[edit]

Slugs' bodies are made up mostly of water and, without a full-sized shell, their soft tissues are prone to desiccation. They must generate protective mucus to survive. Many species are most active following rainfall or during nighttime since there is increased moisture on the ground. In drier conditions, they hide in damp places such as under tree bark, fallen logs, rocks and manmade structures, such as planters, to help retain body moisture.[4] Like all other gastropods, they undergo torsion (a 180° twisting of the internal organs) during development. Internally, slug anatomy clearly shows the effects of this rotation—but externally, the bodies of slugs appear more or less symmetrical, except the pneumostome, which is on one side of the animal, normally the right-hand side.

Slugs produce two types of mucus: one is thin and watery, and the other thick and sticky. Both kinds are hygroscopic. The thin mucus spreads from the foot's centre to its edges, whereas the thick mucus spreads from front to back. Slugs also produce thick mucus that coats the whole body of the animal.[4] The mucus secreted by the foot contains fibres that help prevent the slug from slipping down vertical surfaces.

The "slime trail" a slug leaves behind has some secondary effects: other slugs coming across a slime trail can recognise the slime trail as produced by one of the same species, which is useful in finding a mate. Following a slime trail is also part of the hunting behaviour of some carnivorous slugs.[4] Body mucus provides some protection against predators, as it can make the slug hard to pick up and hold by a bird's beak, for example, or the mucus itself can be distasteful.[10] Some slugs can also produce very sticky mucus which can incapacitate predators and can trap them within the secretion.[11] Some species of slug, such as Limax maximus, secrete slime cords to suspend a pair during copulation.

Reproduction

[edit]

Slugs are hermaphrodites, having both female and male reproductive organs.[12] Once a slug has located a mate, they encircle each other and sperm is exchanged through their protruded genitalia.

Apophallation has been reported only in some species of banana slug (Ariolimax) and one species of Deroceras. In the banana slugs, the penis sometimes becomes trapped inside the body of the partner. Apophallation allows the slugs to separate themselves by one or both of the slugs chewing off the other's or its own penis. Once the penis has been discarded, banana slugs are still able to mate using only the female parts of the reproductive system.[12][13][14]

In a temperate climate, slugs usually live one year outdoors. In greenhouses, many adult slugs may live for more than one year.[15]

Ecology

[edit]Slugs play an important role in the ecosystem by eating decaying plant material and fungi.[16] Most carnivorous slugs on occasion also eat dead specimens of their own kind.

Feeding habits

[edit]

Most species of slugs are generalists, feeding on a broad spectrum of organic materials, including leaves from living plants, lichens, mushrooms, and even carrion.[16][17] Some slugs are predators and eat other slugs and snails, or earthworms.[16][18]

Slugs can feed on a wide variety of vegetables and herbs,[19] including flowers such as petunias, chrysanthemums, daisies, lobelia, lilies, dahlias, narcissus, gentians, primroses, tuberous begonias, hollyhocks, marigolds, and fruits such as strawberries.[20] They also feed on carrots, peas, apples, and cabbage that are offered as a sole food source.[17]

Slugs from different families are fungivores. It is the case in the Philomycidae (e. g. Philomycus carolinianus and Phylomicus flexuolaris) and Ariolimacidae (Ariolimax californianus), which respectively feed on slime molds (myxomycetes) and mushrooms (basidiomycetes).[17] Species of mushroom producing fungi used as food source by slugs include milk-caps (Lactarius spp.), the oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) and the penny bun (Boletus edulis). Other genera such as Agaricus, Pleurocybella and Russula are also eaten by slugs. Slime molds used as food source by slugs include Stemonitis axifera and Symphytocarpus flaccidus.[17] Some slugs are selective towards certain parts or developmental stages of the fungi they eat, though this is very variable. Depending on the species and other factors, slugs eat only fungi at specific stages of development. In other cases, whole mushrooms can be eaten, without any selection or bias towards ontogenetic stages.[17]

Predators

[edit]Slugs are preyed upon by various vertebrates and invertebrates. The predation of slugs has been the subject of studies for at least a century. Because some species of slugs are considered agricultural pests, research investments have been made to discover and investigate potential predators in order to establish biological control strategies.[21]

Vertebrates

[edit]Slugs are preyed upon by virtually every major vertebrate group. With many examples among reptiles, birds, mammals, amphibians and fish, vertebrates can occasionally feed on, or be specialised predators of, slugs.[21] Fish that feed on slugs include the brown trout (Salmo trutta), which occasionally feeds on Arion circumscriptus, an arionid slug.[21] Similarly, the shortjaw kokopu (Galaxias postvectis) includes slugs in its diet.[22] Amphibians such as frogs and toads have long been regarded as important predators of slugs. Among them are species in the genus Bufo, Rhinella and Ceratophrys.[21]

Reptiles that feed on slugs include mainly snakes and lizards.[21] Some colubrid snakes are known predators of slugs. Coastal populations of the garter snake, Thamnophis elegans, have a specialised diet consisting of slugs, such as Ariolimax, while inland populations have a generalized diet.[23] One of its congeners, the Northwestern garter snake (Thamnophis ordinoides), is not a specialized predator of slugs but occasionally feeds on them. The redbelly snake (Storeria occipitomaculata) and the brown snake (Storeria dekayi) feed mainly but not solely on slugs, while some species in the genus Dipsas (e.g. Dipsas neuwiedi) and the common slug eater snake (Duberria lutrix), are exclusively slug eaters.[21][24] Several lizards include slugs in their diet. This is the case in the slowworm (Anguis fragilis), the bobtail lizard (Tiliqua rugosa), the she-oak skink (Cyclodomorphus casuarinae) and the common lizard (Zootoca vivipara).[21][25][26]

Birds that prey upon slugs include common blackbirds (Turdus merula), starlings (Sturnus vulgaris), rooks (Corvus frugilegus), jackdaws (Corvus monedula), owls, vultures and ducks. Studies on slug predation also cite fieldfares (feeding on Deroceras reticulatum), redwings (feeding on Limax and Arion), thrushes (on Limax and Arion ater), red grouse (on Deroceras and Arion hortensis), game birds, wrynecks (on Limax flavus), rock doves and charadriiform birds as slug predators.[21]

Mammals that eat slugs include foxes, badgers and hedgehogs.[27][28]

Invertebrates

[edit]Beetles in the family Carabidae, such as Carabus violaceus and Pterostichus melanarius, are known to feed on slugs.[29][30] Ants are a common predator of slugs; some ant species are deterred by the slug's mucus coating, while others such as driver ants will roll the slug in dirt to absorb its mucus.

Parasites and parasitoids

[edit]Slugs are parasitised by several organisms, including acari[31][32] and a wide variety of nematodes.[33][34] The slug mite, Riccardoella limacum, is known to parasitise several dozen species of molluscs, including many slugs, such as Deroceras reticulatum, Arianta arbustorum, Arion ater, Arion hortensis, Limax maximus, Tandonia budapestensis, Milax gagates, and Tandonia sowerbyi.[31][32] R. limacum can often be seen swarming about their host's body, and live in its respiratory cavity.

Several species of nematodes are known to parasitise slugs. The nematode worms Agfa flexilis and Angiostoma limacis respectively live in the salivary glands and rectum of Limax maximus.[35] Species of widely known medical importance pertaining to the genus Angiostrongylus are also parasites of slugs. Both Angiostrongylus costaricensis and Angiostrongylus cantonensis, a meningitis-causing nematode, have larval stages that can only live in molluscs, including slugs, such as Limax maximus.[33]

Insects such as dipterans are known parasitoids of molluscs. To complete their development, many dipterans use slugs as hosts during their ontogeny. Some species of blow-flies (Calliphoridae) in the genus Melinda are known parasitoids of Arionidae, Limacidae and Philomycidae. Flies in the family Phoridae, specially those in the genus Megaselia, are parasitoids of Agriolimacidae, including many species of Deroceras.[36] House flies in the family Muscidae, mainly those in the genus Sarcophaga, are facultative parasitoids of Arionidae.[37]

Behavior

[edit]

When attacked, slugs can contract their body, making themselves harder and more compact and more still and round. By doing this, they become firmly attached to the substrate. This, combined with the slippery mucus they produce, makes slugs more difficult for predators to grasp. The unpleasant taste of the mucus is also a deterrent.[10] Slugs can also incapacitate predators through the production of a highly sticky and elastic mucus which can trap predators in the secretion.[11]

Some species present different response behaviors when attacked, such as the Kerry slug. In contrast to the general behavioral pattern, the Kerry slug retracts its head, lets go of the substrate, rolls up completely, and stays contracted in a ball-like shape.[38] This is a unique feature among all the Arionidae,[39] and among most other slugs.[38] Some slugs can self-amputate (autotomy) a portion of their tail to help the slug escape from a predator.[40] Some slug species hibernate underground during the winter in temperate climates, but in other species, the adults die in the autumn.[20]

Intra- and inter-specific agonistic behavior is documented, but varies greatly among slug species. Slugs often resort to aggression, attacking both conspecifics and individuals from other species when competing for resources. This aggressiveness is also influenced by seasonality, because the availability of resources such as shelter and food may be compromised due to climatic conditions. Slugs are prone to attack during the summer, when the availability of resources is reduced. During winter, the aggressive responses are substituted by a gregarious behavior.[41]

Human relevance

[edit]The great majority of slug species are harmless to humans and to their interests, but a small number of species are serious pests of agriculture and horticulture. They can destroy foliage faster than plants can grow, thus killing even fairly large plants. They also feed on fruits and vegetables prior to harvest, making holes in the crop, which can make individual items unsuitable to sell for aesthetic reasons, and can make the crop more vulnerable to rot and disease.[42] Excessive buildup of slugs within some wastewater treatment plants with inadequate screening have been found to cause process issues resulting in increased energy and chemical use.[43]

In a few rare cases, humans have developed Angiostrongylus cantonensis-induced meningitis from eating raw slugs.[44] Live slugs that are accidentally eaten with improperly cleaned vegetables (such as lettuce), or improperly cooked slugs (for use in recipes requiring larger slugs such as banana slugs), can act as a vector for a parasitic infection in humans.[34][45]

Prevention

[edit]As control measures, baits are commonly used in both agriculture and the garden. In recent years, iron phosphate baits have emerged and are preferred over the more toxic metaldehyde, especially because domestic or wild animals may be exposed to the bait. The environmentally safer iron phosphate has been shown to be at least as effective as baits.[46] Methiocarb baits are no longer widely used. Parasitic nematodes (Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita) are a commercially available biological control method that are effective against a wide range of common slug species. The nematodes are applied in water and actively seek out slugs in the soil and infect them, leading to the death of the slug. This control method is suitable for use in organic growing systems.

Other slug control methods are generally ineffective on a large scale, but can be somewhat useful in small gardens. These include beer traps,[47][48] diatomaceous earth,[49] crushed eggshells, coffee grounds, and copper.[50] Salt kills slugs by causing water to leave the body owing to osmosis[51] but this is not used for agricultural control as high soil salinity is detrimental to crops.[citation needed][52] Conservation tillage worsens slug infestations. Hammond et al. 1999 find maize/corn and soybean in the US to be more severely affected under low till because this increases organic matter, thus providing food and shelter.[53]

Gallery

[edit]-

A dung beetle (Geotrupes stercorarius) moving a dead slug.

-

Slugs eating vegetables.

-

Limax cinereoniger, the world's largest terrestrial slug.

-

An illustration by Joseph Smit of a bicolored antpitta catching a slug.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "How to be sluggish", Tuatara, 25 (2): 48–63

- ^ White, T. R.; Conrad, M. M.; Tseng, R.; Balayan, S.; Golding, R.; de Frias Martins, A. M.; Dayrat, B. A. (2011). "Ten new complete mitochondrial genomes of pulmonates (Mollusca: Gastropoda) and their impact on phylogenetic relationships". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 11 (1): 295. Bibcode:2011BMCEE..11..295W. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-295. PMC 3198971. PMID 21985526.

- ^ Kocot, Kevin (December 2013). "Phylogenomics supports Panpulmonata: Opisthobranch paraphyly and key evolutionary steps in a major radiation of gastropod molluscs". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 69 (2): 764–771 – via Science Direct.

- ^ a b c d Denny, M. W.; Gosline, J. M. (1980). "The physical properties of the pedal mucus of the terrestrial slug, Ariolimax columbianus" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 88 (1): 375–393. doi:10.1242/jeb.88.1.375.

- ^ Loest, R. A. (1979). "Ammonia Volatilization and Absorption by Terrestrial Gastropods_ a Comparison between Shelled and Shell-Less Species". Physiological Zoology. 52 (4): 461–469. doi:10.1086/physzool.52.4.30155937. JSTOR 30155937. S2CID 87142440.

- ^ a b Branson, B. A (1980). "The recent Gastropoda of Oklahoma, Part VIII. The slug families Limacidae, Arionidae, Veronicellidae, and Philomycidae". Proceedings of the Oklahoma Academy of Science. 60: 29–35.

- ^ Alonso, M. R.; Ibañe, M. (1981). "Estudio de Parmacella valenciannesii Webb & Van Beneden, 1836, y consideraciones sobre la posicion sistematica de la familia Parmacellidae (Mollusca, Pulmonata, Stylommatophora)". Boletín de la Sociedad de Historia Natural de les Baleares. 25: 103–124.

- ^ Dayrat, B. (2009). "Review of the current knowledge of the systematics of Onchidiidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Pulmonata) with a checklist of nominal species". Zootaxa. 2068: 1–26. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2068.1.1. S2CID 4821033.

- ^ Schilthuizen, M.; Thome, J. W. (2008). "Valiguna flava (Heynemann, 1885) from Indonesia and Malaysia: Redescription and Comparison with Valiguna siamensis (Martens, 1867)(Gastropoda: Soleolifera: Veronicellidae)". Veliger. 50 (3): 163–170.

- ^ a b Nixon, P. "Slugs". Home, Yard & Garden Pest Newsletter. College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ^ a b Gould, John; Valdez, Jose W.; Upton, Rose (8 February 2019). "Adhesive defence mucus secretions in the red triangle slug (Triboniophorus graeffei) can incapacitate adult frogs". Ethology. 125 (8): 587–591. Bibcode:2019Ethol.125..587G. doi:10.1111/eth.12875. S2CID 92677691.

- ^ a b "Perverted cannibalistic hermaphrodites haunt the Pacific Northwest! " The Oyster's Garter". Theoystersgarter.com. 24 March 2008. Archived from the original on 13 April 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ Reise, H; Hutchinson, J.M.C. (2002). "Penis-biting slugs: wild claims and confusions" (PDF). Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 17 (4): 163. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02453-9. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ Leonard, J.L.; Pearse, J.S.; Harper, A.B. (2002). "Comparative reproductive biology of Ariolimax californicus and A. dolichophallus (Gastropoda; Stylommiatophora)". Invertebrate Reproduction & Development. 41 (1–3): 83–93. Bibcode:2002InvRD..41...83L. doi:10.1080/07924259.2002.9652738. S2CID 83829239.

- ^ "Slugs and Their Management, HYG-2010-95". 4 April 2005. Archived from the original on 4 April 2005. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c "What Do Slugs Eat?". animals.mom.me. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Keller, H. W.; Snell, K. L. (2002). "Feeding activities of slugs on Myxomycetes and macrofungi". Mycologia. 94 (5): 757–760. doi:10.2307/3761690. JSTOR 3761690. PMID 21156549. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ "Worm-eating slug found in garden (video)". BBC News. 10 July 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ "What Do Slugs Eat?". Slug Cuisine. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ a b Sandy; Misner, L; Balog. "Arion lusitanicus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h South, A. (1992). Terrestrial Slugs: Biology, ecology and control. Boundary Row, London, UK: Chapman & Hall. pp. 428 pp. ISBN 978-0412368103.

- ^ McDowall, R. M.; Main, M. R.; West, D. W.; Lyon, G. L. (1996). "Terrestrial and benthic foods in the diet of the shortjawed kokopu, Galaxias postvectis Clarke (Teleostei: Galaxiidae)". New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 30 (2): 257–269. Bibcode:1996NZJMF..30..257M. doi:10.1080/00288330.1996.9516713.

- ^ Britt, E. J.; Hicks, J. W.; Bennett, A. F. (2006). "The energetic consequences of dietary specialization in populations of the garter snake, Thamnophis elegans". Journal of Experimental Biology. 209 (16): 3164–3169. doi:10.1242/jeb.02366. PMID 16888064.

- ^ Maia, T; Dorigo, T. A.; Gomes, S. R.; Santos, S. B.; Rocha, C. F. D. (2012). "Sibynomorphus neuwiedi (Ihering, 1911) (Serpentes; Dipsadidae) and Potamojanuarius lamellatus (Semper, 1885) (Gastropoda; Veronicellidae): a trophic relationship revealed". Biotemas. 25 (1): 211–213. doi:10.5007/2175-7925.2012v25n1p211. ISSN 2175-7925.

- ^ Avery, R. A. (1966). "Food and feeding habits of the Common lizard (Lacerta vivipara) in the west of England". Journal of Zoology. 149 (2): 115–121. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1966.tb03886.x.

- ^ Hewer, A. M. (1948). "Tazmanian lizards" (PDF). Tazmanian Naturalist. 1 (3): 8–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2013.

- ^ "Slug Control". Cardiff.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ "Ecological Benefits of Slugs". thenest.com. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ Brandmayr, P.; Paill, W.; et al. (2000). "Slugs as prey for larvae and imagines of Carabus violaceus (Coleoptera: Carabidae)". Natural History and Applied Ecology of Carabid Beetles. Sofia, Moscow: PENSOFT Publishers. pp. 221–227. ISBN 9789546421005. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ Symondson, W. O. C.; Glen, D. M.; Erickson, M. L.; Liddell, J. E.; Langdon, C. J. (2000). "Do earthworms help to sustain the slug predator Pterostichus melanarius (Coleoptera: Carabidae) within crops? Investigations using monoclonal antibodies". Molecular Ecology. 9 (9): 1279–1292. Bibcode:2000MolEc...9.1279S. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01006.x. PMID 10972768. S2CID 23921693.

- ^ a b Baker, R. A. (1978). "The food of Riccardoella limacum (Schrank) – Acari-Trombidiformes and its relationship with pulmonate molluscs". Journal of Natural History. 4 (4): 521–530. doi:10.1080/00222937000770481.

- ^ a b Barker, G. M.; Ramsay, G. W. (1978). "The slug mite Riccardoella limacum (Acari: Ereynetidae) in New Zealand" (PDF). New Zealand Entomologist. 6 (4): 441–443. doi:10.1080/00779962.1978.9722316. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2008.

- ^ a b Teixeira, C. G.; Thiengo, S. C.; Thome, J. W.; Medeiros, A. B.; Camillo-Coura, L.; Agostini, A. A. (1993). "On the diversity of mollusc intermediate hosts of Angiostrongylus costaricensis Morera & Cespedes, 1971 in southern Brazil". Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 88 (3): 487–9. doi:10.1590/S0074-02761993000300020. PMID 8107609.

- ^ a b Senanayake, S. N.; Pryor, D. S.; Walker, J.; Konecny, P. (2003)."First report of human angiostrongyliasis acquired in Sydney" Archived 30 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine. The Medical Journal of Australia 179 (8): 430–431.

- ^ Taylor J. W. (1902). Part 8, pages 1–52. Monograph of the land and freshwater Mollusca of the British Isles. Testacellidae. Limacidae. Arionidae. Taylor Brothers, Leeds. Introduction page XV., pages 34–52.

- ^ Robinson, W. H.; Foote, B. A. (1968). "Biology and Immature Stages of Megaselia aequalis, a Phorid Predator of Slug Eggs". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 61 (6): 1587–1594. doi:10.1093/aesa/61.6.1587.

- ^ Coupland, J. B. (2004). "Chapter 3: Dipteras as predators and parasitoids of terrestrial gastropods, with emphasis on Phoridae, Calliphoridae, Sarcophagidae, Muscidae and Fannidae". In Barker, G. M (ed.). Natural Enemies of Terrestrial Molluscs. Wallingford, Oxfordshire, UK: CABI Publishing. pp. 88–124. ISBN 978-0851993195.

- ^ a b

"Forestry and Kerry Slug Guidelines" (PDF). Forest Service Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. 12 July 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) 9 pp. - ^ Kerney, M. P; Cameron, A. D. & Jungbluth, J. H. (1983). Die Landschnecken Nord- und Mitteleuropas (in German). Hamburg and Berlin: Verlag Paul Parey. p. 138. ISBN 978-3-490-17918-0.

- ^ Pekarinen, E. (1994). "Autotomy in arionid and limacid slug". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 60 (1): 19–23. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.873.8562. doi:10.1093/mollus/60.1.19.

- ^ Rollo, C. D.; Wellington, W. G. (1979). "Intra- and inter-specific agonistic behavior among terrestrial slugs (Pulmonata: Stylommatophora)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 57 (4): 846–855. doi:10.1139/z79-104.

- ^ "SlugClear Ultra: Highly efficient protection against slugs and snails | Gardening tips and advice". LoveTheGarden.com. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ Thompson, M. (2018) 'Evaluating Opportunities and Barriers to Improving the Energy Efficiency of Small Nebraska Wastewater Treatment Plants', pp.83 Archived 6 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Health and Medicals News – Man's brain infected by eating slugs". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 15 March 2006.

- ^ Anna Salleh (20 October 2003). "Man's brain infected by eating slugs". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "Less toxic iron phosphate slug bait proves effective". Extension.oregonstate.edu. 25 February 2008. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ "~ Slug Traps ~ Death by Beer Offers and Reviews". Gardening-guru.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 November 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "How to Get Rid of Slugs and Snails". asthegardenturns.com. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ "Using Diatomaceous Earth for Slugs". Slug Cuisine. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ "Guide to Using Copper Slug Tape". Slug Cuisine. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ "Slugs and Osmosis". Newton.dep.anl.gov. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ Shrivastava 1, Kumar 2, Pooja 1, Rajesh 2 (2015). "Soil salinity: A serious environmental issue and plant growth promoting bacteria as one of the tools for its alleviation". Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 22 (2): 123–131 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Capinera, John (2020). Handbook of vegetable pests (2 ed.). London, San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-814488-6. OCLC 1152284558. ISBN 9780128144893.

Further reading

[edit]- Burton, D. W. (January 1982). "How to be sluggish". Tuatara. 25 (2): 48–63.

External links

[edit] Media related to Slug at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Slug at Wikimedia Commons- Slugs and Their Management. Ohio State University Extension.

- "The Secret Lives of Jumping Slugs". Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 9 February 2010. The Nature Conservancy.

- Land Slugs and Snails and Their Control. USDA Farmer's Bulletin No. 1895. Revised 1959. Hosted by the UNT Government Documents Department

- Slugs of Florida. University of Florida IFAS