North American Free Trade Agreement

North American Free Trade Agreement | |

|---|---|

| 1994–2020 | |

| |

| Languages | |

| Type | Free trade area |

| Member states | Canada Mexico United States |

| History | |

• Effective | January 1, 1994 |

• USMCA in force | July 1, 2020 |

| Area | |

• Total | 21,578,137 km2 (8,331,365 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 7.4 |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 490,000,000 |

• Density | 22.3/km2 (57.8/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $24.8 trillion[1] |

• Per capita | $50,700 |

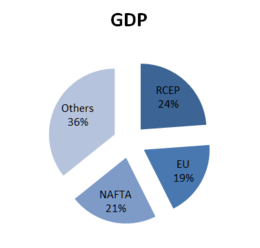

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA /ˈnæftə/ NAF-tə; Spanish: Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte, TLCAN; French: Accord de libre-échange nord-américain, ALÉNA) was an agreement signed by Canada, Mexico, and the United States that created a trilateral trade bloc in North America. The agreement came into force on January 1, 1994, and superseded the 1988 Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement between the United States and Canada. The NAFTA trade bloc formed one of the largest trade blocs in the world by gross domestic product.

The impetus for a North American free trade zone began with U.S. president Ronald Reagan, who made the idea part of his 1980 presidential campaign. After the signing of the Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement in 1988, the administrations of U.S. president George H. W. Bush, Mexican president Carlos Salinas de Gortari, and Canadian prime minister Brian Mulroney agreed to negotiate what became NAFTA. Each submitted the agreement for ratification in their respective capitals in December 1992, but NAFTA faced significant opposition in both the United States and Canada. All three countries ratified NAFTA in 1993 after the addition of two side agreements, the North American Agreement on Labor Cooperation (NAALC) and the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC).

Passage of NAFTA resulted in the elimination or reduction of barriers to trade and investment between the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The effects of the agreement regarding issues such as employment, the environment, and economic growth have been the subject of political disputes. Most economic analyses indicated that NAFTA was beneficial to the North American economies and the average citizen,[2][3][4] but harmed a small minority of workers in industries exposed to trade competition.[5][6] Economists held that withdrawing from NAFTA or renegotiating NAFTA in a way that reestablished trade barriers would have adversely affected the U.S. economy and cost jobs.[7][8][9] However, Mexico would have been much more severely affected by job loss and reduction of economic growth in both the short term and long term.[10]

After U.S. President Donald Trump took office in January 2017, he sought to replace NAFTA with a new agreement, beginning negotiations with Canada and Mexico. In September 2018, the United States, Mexico, and Canada reached an agreement to replace NAFTA with the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), and all three countries had ratified it by March 2020. NAFTA remained in force until USMCA was implemented.[11] In April 2020, Canada and Mexico notified the U.S. that they were ready to implement the agreement.[12] The USMCA took effect on July 1, 2020, replacing NAFTA.

Negotiation, signing, ratification, and revision (1988–94)

Negotiation

The impetus for a North American free trade zone began with U.S. president Ronald Reagan, who made the idea part of his campaign when he announced his candidacy for the presidency in November 1979.[13] Canada and the United States signed the Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in 1988, and shortly afterward Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari decided to approach U.S. president George H. W. Bush to propose a similar agreement in an effort to bring in foreign investment following the Latin American debt crisis.[13] As the two leaders began negotiating, the Canadian government under Prime Minister Brian Mulroney feared that the advantages Canada had gained through the Canada–US FTA would be undermined by a US–Mexican bilateral agreement, and asked to become a party to the US–Mexican talks.[14]

Signing

Following diplomatic negotiations dating back to 1990, the leaders of the three nations signed the agreement in their respective capitals on December 17, 1992.[15] The signed agreement then needed to be ratified by each nation's legislative or parliamentary branch.

Ratification

Canada

The earlier Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement had been controversial and divisive in Canada, and featured as an issue in the 1988 Canadian election. In that election, more Canadians voted for anti-free trade parties (the Liberals and the New Democrats), but the split of the votes between the two parties meant that the pro-free trade Progressive Conservatives (PCs) came out of the election with the most seats and so took power. Mulroney and the PCs had a parliamentary majority and easily passed the 1987 Canada–US FTA and NAFTA bills. However, Mulroney was replaced as Conservative leader and prime minister by Kim Campbell. Campbell led the PC party into the 1993 election where they were decimated by the Liberal Party under Jean Chrétien, who campaigned on a promise to renegotiate or abrogate NAFTA. Chrétien subsequently negotiated two supplemental agreements with Bush, who had subverted the LAC[16] advisory process[17] and worked to "fast track" the signing prior to the end of his term, ran out of time and had to pass the required ratification and signing of the implementation law to incoming president Bill Clinton.[18]

United States

Before sending it to the United States Senate, Clinton added two side agreements, the North American Agreement on Labor Cooperation (NAALC) and the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC), to protect workers and the environment, and to also allay the concerns of many House members. The U.S. required its partners to adhere to environmental practices and regulations similar to its own.[citation needed] After much consideration and emotional discussion, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the North American Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act on November 17, 1993, 234–200. The agreement's supporters included 132 Republicans and 102 Democrats. The bill passed the Senate on November 20, 1993, 61–38.[19] Senate supporters were 34 Republicans and 27 Democrats. Republican Representative David Dreier of California, a strong proponent of NAFTA since the Reagan administration, played a leading role in mobilizing support for the agreement among Republicans in Congress and across the country.[20][21]

Chicago Congressman Luis Gutiérrez in particular was a vocal opponent of NAFTA, ultimately voting against the measure because of what he considered its failure to sufficiently provide for displaced worker retraining, protections against American job loss, and protections of collective bargaining rights for Mexican workers.[22] He criticized the role of Rahm Emanuel in particular for the deficiencies.[23]

The U.S. required its partners to adhere to environmental practices and regulations similar to its own.[24]

Clinton signed it into law on December 8, 1993; the agreement went into effect on January 1, 1994.[25][26] At the signing ceremony, Clinton recognized four individuals for their efforts in accomplishing the historic trade deal: Vice President Al Gore, Chairwoman of the Council of Economic Advisers Laura Tyson, Director of the National Economic Council Robert Rubin, and Republican Congressman David Dreier.[27] Clinton also stated that "NAFTA means jobs. American jobs, and good-paying American jobs. If I didn't believe that, I wouldn't support this agreement."[28] NAFTA replaced the previous Canada-US FTA.

Mexico

NAFTA (TLCAN in Spanish) was approved by the Mexican Senate on November 22, 1993, and was published in the Official Gazette of the Federation on December 8, 1993.[29]

The decree implementing NAFTA and the various changes to accommodate NAFTA in Mexican law was promulgated on December 14, 1993, with entry into force on January 1, 1994.[29]

Provisions

The goal of NAFTA was to eliminate barriers to trade and investment between the United States, Canada and Mexico. The implementation of NAFTA on January 1, 1994, brought the immediate elimination of tariffs on more than one-half of Mexico's exports to the U.S. and more than one-third of U.S. exports to Mexico. Within 10 years of the implementation of the agreement, all U.S.–Mexico tariffs were to be eliminated except for some U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico, to be phased out within 15 years.[30] Most U.S.–Canada trade was already duty-free. NAFTA also sought to eliminate non-tariff trade barriers and to protect the intellectual property rights on traded products.

Chapter 20 provided a procedure for the international resolution of disputes over the application and interpretation of NAFTA. It was modeled after Chapter 69 of the Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement.[31]

NAFTA is, in part, implemented by Technical Working Groups composed of government officials from each of the three partner nations.[32]

Intellectual property

The North American Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act made some changes to the copyright law of the United States, foreshadowing the Uruguay Round Agreements Act of 1994 by restoring copyright (within the NAFTA nations) on certain motion pictures which had entered the public domain.[33][34]

Environment

The Clinton administration negotiated a side agreement on the environment with Canada and Mexico, the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC), which led to the creation of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC) in 1994. To alleviate concerns that NAFTA, the first regional trade agreement between a developing country and two developed countries, would have negative environmental impacts, the commission was mandated to conduct ongoing ex post environmental assessment,[35] It created one of the first ex post frameworks for environmental assessment of trade liberalization, designed to produce a body of evidence with respect to the initial hypotheses about NAFTA and the environment, such as the concern that NAFTA would create a "race to the bottom" in environmental regulation among the three countries, or that NAFTA would pressure governments to increase their environmental protections.[36] The CEC has held[when?] four symposia to evaluate the environmental impacts of NAFTA and commissioned 47 papers on the subject from leading independent experts.[37]

Labor

Proponents of NAFTA in the United States emphasized that the pact was a free-trade, not an economic-community, agreement.[38] The freedom of movement it establishes for goods, services and capital did not extend to labor. In proposing what no other comparable agreement had attempted—to open industrialized countries to "a major Third World country"[39]—NAFTA eschewed the creation of common social and employment policies. The regulation of the labor market and or the workplace remained the exclusive preserve of the national governments.[38]

A "side agreement" on enforcement of existing domestic labor law, concluded in August 1993, the North American Agreement on Labour Cooperation (NAALC),[40] was highly circumscribed. Focused on health and safety standards and on child labor law, it excluded issues of collective bargaining, and its "so-called [enforcement] teeth" were accessible only at the end of "a long and tortuous" disputes process".[41] Commitments to enforce existing labor law also raised issues of democratic practice.[38] The Canadian anti-NAFTA coalition, Pro-Canada Network, suggested that guarantees of minimum standards would be "meaningless" without "broad democratic reforms in the [Mexican] courts, the unions, and the government".[42] Later assessment, however, did suggest that NAALC's principles and complaint mechanisms did "create new space for advocates to build coalitions and take concrete action to articulate challenges to the status quo and advance workers’ interests".[43]

Agriculture

From the earliest negotiation, agriculture was a controversial topic within NAFTA, as it has been with almost all free trade agreements signed within the WTO framework. Agriculture was the only section that was not negotiated trilaterally; instead, three separate agreements were signed between each pair of parties. The Canada–U.S. agreement contained significant restrictions and tariff quotas on agricultural products (mainly sugar, dairy, and poultry products), whereas the Mexico–U.S. pact allowed for a wider liberalization within a framework of phase-out periods (it was the first North–South FTA on agriculture to be signed).[clarification needed]

Transportation infrastructure

NAFTA established the CANAMEX Corridor for road transport between Canada and Mexico, also proposed for use by rail, pipeline, and fiber optic telecommunications infrastructure. This became a High Priority Corridor under the U.S. Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991.

Chapter 11 – investor-state dispute settlement procedures

Another contentious issue was the investor-state dispute settlement obligations contained in Chapter 11 of NAFTA.[44] Chapter 11 allowed corporations or individuals to sue Mexico, Canada or the United States for compensation when actions taken by those governments (or by those for whom they are responsible at international law, such as provincial, state, or municipal governments) violated international law.[45]

This chapter has been criticized by groups in the United States,[46] Mexico,[47] and Canada[48] for a variety of reasons, including not taking into account important social and environmental[49] considerations. In Canada, several groups, including the Council of Canadians, challenged the constitutionality of Chapter 11. They lost at the trial level[50] and the subsequent appeal.[51]

Methanex Corporation, a Canadian corporation, filed a US$970 million suit against the United States. Methanex claimed that a California ban on methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), a substance that had found its way into many wells in the state, was hurtful to the corporation's sales of methanol. The claim was rejected, and the company was ordered to pay US$3 million to the U.S. government in costs, based on the following reasoning: "But as a matter of general international law, a non-discriminatory regulation for a public purpose, which is enacted in accordance with due process and, which affects, inter alios, a foreign investor or investment is not deemed expropriatory and compensable unless specific commitments had been given by the regulating government to the then putative foreign investor contemplating investment that the government would refrain from such regulation."[52]

In another case, Metalclad, an American corporation, was awarded US$15.6 million from Mexico after a Mexican municipality refused a construction permit for the hazardous waste landfill it intended to construct in Guadalcázar, San Luis Potosí. The construction had already been approved by the federal government with various environmental requirements imposed (see paragraph 48 of the tribunal decision). The NAFTA panel found that the municipality did not have the authority to ban construction on the basis of its environmental concerns.[53]

In Eli Lilly and Company v. Government of Canada[54] the plaintiff presented a US$500 million claim for the way Canada requires usefulness in its drug patent legislation.[55] Apotex sued the U.S. for US$520 million because of opportunity it says it lost in an FDA generic drug decision.[55]

Lone Pine Resources Inc. v. Government of Canada[56] filed a US$250 million claim against Canada, accusing it of "arbitrary, capricious and illegal" behaviour,[57] because Quebec intends to prevent fracking exploration under the St. Lawrence Seaway.[55]

Lone Pine Resources is incorporated in Delaware but headquartered in Calgary,[57] and had an initial public offering on the NYSE May 25, 2011, of 15 million shares each for $13, which raised US$195 million.[58]

Barutciski acknowledged "that NAFTA and other investor-protection treaties create an anomaly in that Canadian companies that have also seen their permits rescinded by the very same Quebec legislation, which expressly forbids the paying of compensation, do not have the right (to) pursue a NAFTA claim", and that winning "compensation in Canadian courts for domestic companies in this case would be more difficult since the Constitution puts property rights in provincial hands".[57]

A treaty[clarification needed] with China would extend similar rights to Chinese investors, including SOEs.[57]

Chapter 19 – countervailing duty

NAFTA's Chapter 19 was a trade dispute mechanism which subjects antidumping and countervailing duty (AD/CVD) determinations to binational panel review instead of, or in addition to, conventional judicial review.[59] For example, in the United States, review of agency decisions imposing antidumping and countervailing duties are normally heard before the U.S. Court of International Trade, an Article III court. NAFTA parties, however, had the option of appealing the decisions to binational panels composed of five citizens from the two relevant NAFTA countries.[59] The panelists were generally lawyers experienced in international trade law. Since NAFTA did not include substantive provisions concerning AD/CVD, the panel was charged with determining whether final agency determinations involving AD/CVD conformed with the country's domestic law. Chapter 19 was an anomaly in international dispute settlement since it did not apply international law, but required a panel composed of individuals from many countries to re-examine the application of one country's domestic law.[citation needed]

A Chapter 19 panel was expected to examine whether the agency's determination was supported by "substantial evidence". This standard assumed significant deference to the domestic agency. Some of the most controversial trade disputes in recent years, such as the U.S.–Canada softwood lumber dispute, have been litigated before Chapter 19 panels.

Decisions by Chapter 19 panels could be challenged before a NAFTA extraordinary challenge committee. However, an extraordinary challenge committee did not function as an ordinary appeal.[59] Under NAFTA, it only vacated or remanded a decision if the decision involveed a significant and material error that threatens the integrity of the NAFTA dispute settlement system. Since January 2006, no NAFTA party had successfully challenged a Chapter 19 panel's decision before an extraordinary challenge committee.

Adjudication

The roster of NAFTA adjudicators included many retired judges, such as Alice Desjardins, John Maxwell Evans, Constance Hunt, John Richard, Arlin Adams, Susan Getzendanner, George C. Pratt, Charles B. Renfrew and Sandra Day O'Connor.

Impact

Canada

Historical context

In 2008, Canadian exports to the United States and Mexico were at $381.3 billion, with imports at $245.1 billion.[60] According to a 2004 article by University of Toronto economist Daniel Trefler, NAFTA produced a significant net benefit to Canada in 2003, with long-term productivity increasing by up to 15 percent in industries that experienced the deepest tariff cuts.[61] While the contraction of low-productivity plants reduced employment (up to 12 percent of existing positions), these job losses lasted less than a decade; overall, unemployment in Canada has fallen since the passage of the act. Commenting on this trade-off, Trefler said that the critical question in trade policy is to understand "how freer trade can be implemented in an industrialized economy in a way that recognizes both the long-run gains and the short-term adjustment costs borne by workers and others".[62]

A study in 2007 found that NAFTA had "a substantial impact on international trade volumes, but a modest effect on prices and welfare".[63]

According to a 2012 study, with reduced NAFTA trade tariffs, trade with the United States and Mexico only increased by a modest 11% in Canada compared to an increase of 41% for the U.S. and 118% for Mexico.[64]: 3 Moreover, the U.S. and Mexico benefited more from the tariff reductions component, with welfare increases of 0.08% and 1.31%, respectively, with Canada experiencing a decrease of 0.06%.[64]: 4

Current issues

According to a 2017 report by the New York City based public policy think tank report, Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), bilateral trade in agricultural products tripled in size from 1994 to 2017 and is considered to be one of the largest economic effects of NAFTA on U.S.-Canada trade with Canada becoming the U.S. agricultural sectors' leading importer.[65] Canadian fears of losing manufacturing jobs to the United States did not materialize with manufacturing employment holding "steady". However, with Canada's labour productivity levels at 72% of U.S. levels, the hopes of closing the "productivity gap" between the two countries were also not realized.[65]

According to a 2018 Sierra Club report, Canada's commitments under NAFTA and the Paris agreement conflicted. The Paris commitments were voluntary, and NAFTA's were compulsory.[66]

According to a 2018 report by Gordon Laxter published by the Council of Canadians, NAFTA's Article 605, energy proportionality rule ensures that Americans had "virtually unlimited first access to most of Canada's oil and natural gas" and Canada could not reduce oil, natural gas and electricity exports (74% its oil and 52% its natural gas) to the U.S., even if Canada was experiencing shortages. These provisions that seemed logical when NAFTA was signed in 1993 are no longer appropriate.[67]: 4 The Council of Canadians promoted environmental protection and was against NAFTA's role in encouraging development of the tar sands and fracking.[67]

US President Donald Trump, angered by Canada's dairy tax of "almost 300%", threatened to leave Canada out of the NAFTA.[68] Since 1972, Canada has been operating on a "supply management" system, which the United States is attempting to pressure it out of, specifically focusing on the dairy industry. However, this has not yet taken place, as Quebec, which holds approximately half the country's dairy farms, still supports supply management.[68]

Mexico

Maquiladoras (Mexican assembly plants that take in imported components and produce goods for export) became the landmark of trade in Mexico. They moved to Mexico from the United States[citation needed], hence the debate over the loss of American jobs. Income in the maquiladora sector had increased 15.5% since the implementation of NAFTA in 1994.[69] Other sectors also benefited from the free trade agreement, and the share of exports to the U.S. from non-border states increased in the last five years[when?] while the share of exports from border states decreased. This allowed for rapid growth in non-border metropolitan areas such as Toluca, León, and Puebla, which were all larger in population than Tijuana, Ciudad Juárez, and Reynosa.

The overall effect of the Mexico–U.S. agricultural agreement is disputed. Mexico did not invest in the infrastructure necessary for competition, such as efficient railroads and highways. This resulted in more difficult living conditions for the country's poor. Mexico's agricultural exports increased 9.4 percent annually between 1994 and 2001, while imports increased by only 6.9 percent a year during the same period.[70]

One of the most affected agricultural sectors was the meat industry. Mexico went from a small player in the pre-1994 U.S. export market to the second largest importer of U.S. agricultural products in 2004, and NAFTA may have been a major catalyst for this change. Free trade removed the hurdles that impeded business between the two countries, so Mexico provided a growing market for meat for the U.S., and increased sales and profits for the U.S. meat industry. A coinciding noticeable increase in the Mexican per capita GDP greatly changed meat consumption patterns as per capita meat consumption grew.[71]

One of concerns raised by the implementation of NAFTA in Mexico was wealth inequality. National Bureau of Economic Research found that NAFTA increased the wage gap between the lowest and highest earners, directly affecting wealth inequality.[72] According to Global Trade Watch, under NAFTA Mexico observed a decline in real average annual wages, with this decline mainly affecting those who earned the least - the real average wage of minimum wage workers decreased by 14 percent. GTW concluded that "inflation-adjusted wages for virtually every category of Mexican worker decreased over NAFTA’s first six years, even as hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs were being shifted from the United States to Mexico".[73] Similar effects were found in a study published in the International Journal of Economic Sciences, which found that NAFTA had a direct impact on wage inequality in Mexico; from 1994 onwards, the wage gap between the poorest and the richest workers noticeably increased.[74]

Production of corn in Mexico increased since NAFTA. However, internal demand for corn had increased beyond Mexico's supply to the point where imports became necessary, far beyond the quotas Mexico originally negotiated.[75] Zahniser & Coyle pointed out that corn prices in Mexico, adjusted for international prices, have drastically decreased, but through a program of subsidies expanded by former president Vicente Fox, production remained stable since 2000.[76] Reducing agricultural subsidies, especially corn subsidies, was suggested as a way to reduce harm to Mexican farmers.[77]

A 2001 Journal of Economic Perspectives review of the existing literature found that NAFTA was a net benefit to Mexico.[4] By 2003, 80% of the commerce in Mexico was executed only with the U.S. The commercial sales surplus, combined with the deficit with the rest of the world, created a dependency in Mexico's exports. These effects were evident in the 2001 recession, which resulted in either a low rate or a negative rate in Mexico's exports.[78]

A 2015 study found that Mexico's welfare increased by 1.31% as a result of the NAFTA tariff reductions and that Mexico's intra-bloc trade increased by 118%.[64] Inequality and poverty fell in the most globalization-affected regions of Mexico.[79] 2013 and 2015 studies showed that Mexican small farmers benefited more from NAFTA than large-scale farmers.[80][81]

NAFTA had also been credited with the rise of the Mexican middle class. A Tufts University study found that NAFTA lowered the average cost of basic necessities in Mexico by up to 50%.[82] This price reduction increased cash-on-hand for many Mexican families, allowing Mexico to graduate more engineers than Germany each year.[83]

Growth in new sales orders indicated an increase in demand for manufactured products, which resulted in expansion of production and a higher employment rate to satisfy the increment in the demand. The growth in the maquiladora industry and in the manufacturing industry was of 4.7% in August 2016.[84] Three quarters of the imports and exports are with the U.S.

Tufts University political scientist Daniel W. Drezner argued that NAFTA made it easier for Mexico to transform to a real democracy and become a country that views itself as North American. This has boosted cooperation between the United States and Mexico.[85]

United States

Economists generally agreed that the United States economy benefited overall from NAFTA as it increased trade.[86][87] In a 2012 survey of the Initiative on Global Markets' Economic Experts Panel, 95% of the participants said that, on average, U.S. citizens benefited from NAFTA while none said that NAFTA hurt US citizens, on average.[3] A 2001 Journal of Economic Perspectives review found that NAFTA was a net benefit to the United States.[4] A 2015 study found that US welfare increased by 0.08% as a result of NAFTA tariff reductions, and that US intra-bloc trade increased by 41%.[64]

A 2014 study on the effects of NAFTA on US trade jobs and investment found that between 1993 and 2013, the US trade deficit with Mexico and Canada increased from $17.0 to $177.2 billion, displacing 851,700 US jobs.[88]

In 2015, the Congressional Research Service concluded that the "net overall effect of NAFTA on the US economy appears to have been relatively modest, primarily because trade with Canada and Mexico accounts for a small percentage of US GDP. However, there were worker and firm adjustment costs as the three countries adjusted to more open trade and investment among their economies." The report also estimated that NAFTA added $80 billion to the US economy since its implementation, equivalent to a 0.5% increase in US GDP.[89]

The US Chamber of Commerce credited NAFTA with increasing U.S. trade in goods and services with Canada and Mexico from $337 billion in 1993 to $1.2 trillion in 2011, while the AFL–CIO blamed the agreement for sending 700,000 American manufacturing jobs to Mexico over that time.[90]

University of California, San Diego economics professor Gordon Hanson said that NAFTA helped the US compete against China and therefore saved US jobs.[91][92] While some jobs were lost to Mexico as a result of NAFTA, considerably more would have been lost to China if not for NAFTA.[91][92]

Trade balances

The US had a trade surplus with NAFTA countries of $28.3 billion for services in 2009 and a trade deficit of $94.6 billion (36.4% annual increase) for goods in 2010. This trade deficit accounted for 26.8% of all US goods trade deficit.[93] A 2018 study of global trade published by the Center for International Relations identified irregularities in the patterns of trade of NAFTA ecosystem using network theory analytical techniques. The study showed that the US trade balance was influenced by tax avoidance opportunities provided in Ireland.[94]

A study published in the August 2008 issue of the American Journal of Agricultural Economics, found NAFTA increased US agricultural exports to Mexico and Canada, even though most of the increase occurred a decade after its ratification. The study focused on the effects that gradual "phase-in" periods in regional trade agreements, including NAFTA, have on trade flows. Most of the increases in members' agricultural trade, which was only recently brought under the purview of the World Trade Organization, was due to very high trade barriers before NAFTA or other regional trade agreements.[95]

Investment

The U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI) in NAFTA countries (stock) was $327.5 billion in 2009 (latest data available)[when?], up 8.8% from 2008.[93] The US direct investment in NAFTA countries was in non-bank holding companies and the manufacturing, finance/insurance, and mining sectors.[93] The foreign direct investment of Canada and Mexico in the United States (stock) was $237.2 billion in 2009 (the latest data available), up 16.5% from 2008.[93][96]

Economy and jobs

In their May 24, 2017 report, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) wrote that the economic impacts of NAFTA on the U.S. economy were modest. In a 2015 report, the Congressional Research Service summarized multiple studies as follows: "In reality, NAFTA did not cause the huge job losses feared by the critics or the large economic gains predicted by supporters. The net overall effect of NAFTA on the U.S. economy appears to have been relatively modest, primarily because trade with Canada and Mexico accounts for a small percentage of U.S. GDP. However, there were worker and firm adjustment costs as the three countries adjusted to more open trade and investment among their economies."[97]: 2

Many American small businesses depended on exporting their products to Canada or Mexico under NAFTA. According to the U.S. Trade Representative, this trade supported over 140,000 small- and medium-sized businesses in the US.[98]

According to University of California, Berkeley professor of economics Brad DeLong, NAFTA had an insignificant impact on US manufacturing.[99] The adverse impact on manufacturing was exaggerated in US political discourse according to DeLong[99] and Harvard economist Dani Rodrik.[100]

According to a 2013 article by Jeff Faux published by the Economic Policy Institute, California, Texas, Michigan and other states with high concentrations of manufacturing jobs were most affected by job loss due to NAFTA.[101] According to a 2011 article by EPI economist Robert Scott, about 682,900 U.S. jobs were "lost or displaced" as a result of the trade agreement.[102] More recent studies agreed with reports by the Congressional Research Service that NAFTA only had a modest impact on manufacturing employment and automation explained 87% of the losses in manufacturing jobs.[103]

Environment

According to a study in the Journal of International Economics, NAFTA reduced pollution emitted by the US manufacturing sector: "On average, nearly two-thirds of the reductions in coarse particulate matter (PM10) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions from the U.S. manufacturing sector between 1994 and 1998 can be attributed to trade liberalization following NAFTA."[104]

According to the Sierra Club, NAFTA contributed to large-scale, export-oriented farming, which led to the increased use of fossil fuels, pesticides and GMO.[105] NAFTA also contributed to environmentally destructive mining practices in Mexico.[105] It prevented Canada from effectively regulating its tar sands industry, and created new legal avenues for transnational corporations to fight environmental legislation.[105] In some cases, environmental policy was neglected in the wake of trade liberalization; in other cases, NAFTA's measures for investment protection, such as Chapter 11, and measures against non-tariff trade barriers threatened to discourage more vigorous environmental policy.[106] The most serious overall increases in pollution due to NAFTA were found in the base metals sector, the Mexican petroleum sector, and the transportation equipment sector in the United States and Mexico, but not in Canada.[107]

Mobility of persons

According to the Department of Homeland Security Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, during fiscal year 2006 (October 2005 – September 2006), 73,880 foreign professionals (64,633 Canadians and 9,247 Mexicans) were admitted into the United States for temporary employment under NAFTA (i.e., in the TN status). Additionally, 17,321 of their family members (13,136 Canadians, 2,904 Mexicans, as well as a number of third-country nationals married to Canadians and Mexicans) entered the U.S. in the treaty national's dependent (TD) status.[108] Because DHS counts the number of the new I-94 arrival records filled at the border, and the TN-1 admission is valid for three years, the number of non-immigrants in TN status present in the U.S. at the end of the fiscal year is approximately equal to the number of admissions during the year. (A discrepancy may be caused by some TN entrants leaving the country or changing status before their three-year admission period has expired, while other immigrants admitted earlier may change their status to TN or TD, or extend TN status granted earlier).

According to the International Organization for Migration, deaths of migrants have been on the rise worldwide with 5,604 deaths in 2016.[109] An increased number of undocumented farmworkers in California may be due to the initial passing of NAFTA.[110]

Canadian authorities estimated that on December 1, 2006, 24,830 U.S. citizens and 15,219 Mexican citizens were in Canada as "foreign workers". These numbers include both entrants under NAFTA and those who entered under other provisions of Canadian immigration law.[111] New entries of foreign workers in 2006 totalled 16,841 U.S. citizens and 13,933 Mexicans.[112]

Disputes and controversies

1992 U.S. presidential candidate Ross Perot

In the second 1992 presidential debate, Ross Perot argued:

We have got to stop sending jobs overseas. It's pretty simple: If you're paying $12, $13, $14 an hour for factory workers and you can move your factory south of the border, pay a dollar an hour for labor, ... have no health care—that's the most expensive single element in making a car—have no environmental controls, no pollution controls and no retirement, and you don't care about anything but making money, there will be a giant sucking sound going south. ... when [Mexico's] jobs come up from a dollar an hour to six dollars an hour, and ours go down to six dollars an hour, and then it's leveled again. But in the meantime, you've wrecked the country with these kinds of deals.[113]

Perot ultimately lost the election, and the winner, Bill Clinton, supported NAFTA, which went into effect on January 1, 1994.

Legal disputes

In 1996, the gasoline additive MMT was brought to Canada by Ethyl Corporation, an American company when the Canadian federal government banned imports of the additive. The American company brought a claim under NAFTA Chapter 11 seeking US$201 million,[114] from the Canadian federal government as well as the Canadian provinces under the Agreement on Internal Trade (AIT). They argued that the additive had not been conclusively linked to any health dangers, and that the prohibition was damaging to their company. Following a finding that the ban was a violation of the AIT,[115] the Canadian federal government repealed the ban and settled with the American company for US$13 million.[116] Studies by Health and Welfare Canada (now Health Canada) on the health effects of MMT in fuel found no significant health effects associated with exposure to these exhaust emissions. Other Canadian researchers and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency disagreed citing studies that suggested possible nerve damage.[117]

The United States and Canada argued for years over the United States' 27% duty on Canadian softwood lumber imports. Canada filed many motions to have the duty eliminated and the collected duties returned to Canada.[118] After the United States lost an appeal before a NAFTA panel, spokesperson for U.S. Trade Representative Rob Portman responded by saying: "we are, of course, disappointed with the [NAFTA panel's] decision, but it will have no impact on the anti-dumping and countervailing duty orders."[119] On July 21, 2006, the United States Court of International Trade found that imposition of the duties was contrary to U.S. law.[120][121]

Change in income trust taxation not expropriation

On October 30, 2007, American citizens Marvin and Elaine Gottlieb filed a Notice of Intent to Submit a Claim to Arbitration under NAFTA, claiming thousands of U.S. investors lost a total of $5 billion in the fall-out from the Conservative Government's decision the previous year to change the tax rate on income trusts in the energy sector. On April 29, 2009, a determination was made that this change in tax law was not expropriation.[122]

Impact on Mexican farmers

Several studies rejected NAFTA responsibility for depressing the incomes of poor corn farmers. The trend existed more than a decade before NAFTA existed. Also, maize production increased after 1994, and there wasn't a measurable impact on the price of Mexican corn because of subsidized[who?] corn from the United States. The studies agreed that the abolition of U.S. agricultural subsidies would benefit Mexican farmers.[123]

Zapatista Uprising in Chiapas, Mexico

Preparations for NAFTA included cancellation of Article 27 of Mexico's constitution, the cornerstone of Emiliano Zapata's revolution in 1910–1919. Under the historic Article 27, indigenous communal landholdings were protected from sale or privatization. However, this barrier to investment was incompatible with NAFTA. Indigenous farmers feared the loss of their remaining land and cheap imports (substitutes) from the US. The Zapatistas labelled NAFTA a "death sentence" to indigenous communities all over Mexico and later declared war on the Mexican state on January 1, 1994, the day NAFTA came into force.[124]

Criticism from 2016 U.S. presidential candidates

In a 60 Minutes interview in September 2015, 2016 presidential candidate Donald Trump called NAFTA "the single worst trade deal ever approved in [the United States]",[125] and said that if elected, he would "either renegotiate it, or we will break it".[126][127] Juan Pablo Castañón, president of the trade group Consejo Coordinador Empresarial, expressed concern about renegotiation and the willingness to focus on the car industry.[128] A range of trade experts said that pulling out of NAFTA would have a range of unintended consequences for the United States, including reduced access to its biggest export markets, a reduction in economic growth, and higher prices for gasoline, cars, fruits, and vegetables.[129] Members of the private initiative in Mexico noted that to eliminate NAFTA, many laws must be adapted by the U.S. Congress. The move would also eventually result in legal complaints by the World Trade Organization.[128] The Washington Post noted that a Congressional Research Service review of academic literature concluded that the "net overall effect of NAFTA on the U.S. economy appears to have been relatively modest, primarily because trade with Canada and Mexico accounts for a small percentage of U.S. GDP".[64]

Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders, opposing the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement, called it "a continuation of other disastrous trade agreements, like NAFTA, CAFTA, and permanent normal trade relations with China". He believes that free trade agreements have caused a loss of American jobs and depressed American wages. Sanders said that America needs to rebuild its manufacturing base using American factories for well-paying jobs for American labor rather than outsourcing to China and elsewhere.[130][131][132]

Policy of the Trump administration

Renegotiation

Shortly after his election, U.S. President Donald Trump said he would begin renegotiating the terms of NAFTA, to resolve trade issues he had campaigned on. The leaders of Canada and Mexico had indicated their willingness to work with the Trump administration.[133] Although vague on the exact terms he sought in a renegotiated NAFTA, Trump threatened to withdraw from it if negotiations failed.[134]

In July 2017, the Trump administration provided a detailed list of changes that it would like to see to NAFTA.[135] The top priority was a reduction in the United States' trade deficit.[135][136] The administration also called for the elimination of provisions that allowed Canada and Mexico to appeal duties imposed by the United States and limited the ability of the United States to impose import restrictions on Canada and Mexico.[135]

Being "consistent with the president's stance on liking trade barriers, liking protectionism", Chad P. Bown of the Peterson Institute for International Economics suggested that the proposed changes would make NAFTA "in many respects less of a free-trade agreement."[135] Additional concerns expressed by the US Trade Representative over subsidized state-owned enterprises and currency manipulation were not thought to apply to Canada and Mexico, but were intended rather to send a message to countries beyond North America.[135]

John Murphy, vice-president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce declared that a number of the proposals tabled by the United States had "little or no support" from the U.S. business and agriculture community."[137] Pat Roberts, the senior U.S. senator from Kansas, said it was not clear "who they're intended to benefit", and called for push back against the anti-NAFTA moves as the "issues affect real jobs, real lives and real people". Kansas is a major agricultural exporter, and farm groups warned that just threatening to leave NAFTA might cause buyers to minimize uncertainty by seeking out non-US sources.[137]

A fourth round of talks included a U.S. demand for a sunset clause that would end the agreement in five years, unless the three countries agreed to keep it in place, a provision U.S. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross has said would allow the countries to kill the deal if it was not working. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau met with the House Ways and Means Committee, since Congress would have to pass legislation rolling back the treaty's provisions if Trump tries to withdraw from the pact.[138]

From June to late August 2018, Canada was sidelined as the United States and Mexico held bilateral talks.[139] On 27 August 2018 Mexico and the United States announced they had reached a bilateral understanding on a revamped NAFTA trade deal that included provisions that would boost automobile production in the U.S.,[140] a 10-year data protection period against generic drug production on an expanded list of products that benefits pharmaceutical companies, particularly US makers producers of high-cost biologic drugs, a sunset clause—a 16-year expiration date with regular 6-year reviews to possibly renew the agreement for additional 16-year terms, and an increased de minimis threshold in which Mexico raised the de minimis value to $100 from $50 regarding online duty- and tax-free purchases.[141][142]

According to an August 30 article in The Economist, Mexico agreed to increase the rules of origin threshold which would mean that 75% as opposed to the previous 62.5% of a vehicle's components must be made in North America to avoid tariffs.[143] Since car makers currently import less expensive components from Asia, under the revised agreement, consumers would pay more for vehicles.[144] As well, approximately 40 to 45 per cent of vehicle components must be made by workers earning a minimum of US$16 per hour, in contrast to the current US$2.30 an hour that a worker earns on average in a Mexican car manufacturing plant.[143][144] The Economist described this as placing "Mexican carmaking into a straitjacket".[143]

Trudeau and Canadian Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland announced that they were willing to join the agreement if it was in Canada's interests.[145] Freeland returned from her European diplomatic tour early, cancelling a planned visit to Ukraine, to participate in NAFTA negotiations in Washington, D.C. in late August.[146] According to an August 31 Canadian Press published in the Ottawa Citizen, key issues under debate included supply management, Chapter 19, pharmaceuticals, cultural exemption, the sunset clause, and de minimis thresholds.[142]

Although President Donald Trump warned Canada on September 1 that he would exclude them from a new trade agreement unless Canada submitted to his demands, it is not clear that the Trump administration had the authority to do so without the approval of Congress.[147]: 34–6 [148][149][150]

On September 30, 2018, the day of the deadline for the Canada–U.S. negotiations, a preliminary deal between the two countries was reached, thus preserving the trilateral pact when the Trump administration submits the agreement before Congress.[151] The new name for the agreement was the "United States—Mexico—Canada Agreement" (USMCA) and came into effect on July 1, 2020.[152][153]

Impact of withdrawing from NAFTA

Following Donald Trump's election to the presidency, a range of trade experts said that pulling out of NAFTA as Trump proposed would have a range of unintended consequences for the U.S., including reduced access to the U.S.'s biggest export markets, a reduction in economic growth, and increased prices for gasoline, cars, fruits, and vegetables.[8] The worst affected sectors would be textiles, agriculture and automobiles.[9][154]

According to Tufts University political scientist Daniel W. Drezner, the Trump administration's desire to return relations with Mexico to the pre-NAFTA era are misguided. Drezner argued that NAFTA made it easier for Mexico to transform to a real democracy and become a country that views itself as North American. If Trump acts on many of the threats that he has made against Mexico, it is not inconceivable that Mexicans would turn to left-wing populist strongmen, as several South American countries have. At the very least, US-Mexico relations would worsen, with adverse implications for cooperation on border security, counterterrorism, drug-war operations, deportations and managing Central American migration.[85]

According to Chad P. Bown (senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics), "a renegotiated NAFTA that would reestablish trade barriers is unlikely to help workers who lost their jobs—regardless of the cause—take advantage of new employment opportunities".[155]

According to Harvard economist Marc Melitz, "recent research estimates that the repeal of NAFTA would not increase car production in the United States".[7] Melitz noted that this would cost manufacturing jobs.[7][clarification needed]

Trans-Pacific Partnership

This section needs to be updated. (February 2021) |

If the original Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) had come into effect, existing agreements such as NAFTA would be reduced to those provisions that do not conflict with the TPP, or that require greater trade liberalization than the TPP.[156] However, only Canada and Mexico would have the prospect of becoming members of the TPP after U.S. President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the agreement in January 2017. In May 2017, the 11 remaining members of the TPP, including Canada and Mexico, agreed to proceed with a revised version of the trade deal without U.S. participation.[157]

American public opinion on NAFTA

The American public was largely divided on its view of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), with a wide partisan gap in beliefs. In a February 2018 Gallup Poll, 48% of Americans said NAFTA was good for the U.S., while 46% said it was bad.[158]

According to a journal from the Law and Business Review of the Americas (LBRA), U.S. public opinion of NAFTA centers around three issues: NAFTA's impact on the creation or destruction of American jobs, NAFTA's impact on the environment, and NAFTA's impact on immigrants entering the U.S.[159]

After President Trump's election in 2016, support for NAFTA became very polarized between Republicans and Democrats. Donald Trump expressed negative views of NAFTA, calling it "the single worst trade deal ever approved in this country".[160] Republican support for NAFTA decreased from 43% support in 2008 to 34% in 2017. Meanwhile, Democratic support for NAFTA increased from 41% support in 2008 to 71% in 2017.[161]

The political gap was especially large in concern to views on free trade with Mexico. As opposed to a favorable view of free trade with Canada, whom 79% of American described as a fair trade partner, only 47% of Americans believed Mexico practices fair trade. The gap widened between Democrats and Republicans: 60% of Democrats believed Mexico is practicing fair trade, while only 28% of Republicans did. This was the highest level from Democrats and the lowest level from Republicans ever recorded by the Chicago Council Survey. Republicans had more negative views of Canada as a fair trade partner than Democrats as well.[161]

NAFTA had strong support from young Americans. In a February 2017 Gallup poll, 73% of Americans aged 18–29 said NAFTA was good for the U.S., showing higher support than any other U.S. age group.[158] It also had slightly stronger support from unemployed Americans than from employed Americans.[162]

See also

- United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA)

- North American integration

- North American Leaders' Summit (NALS)

- Canada's Global Markets Action Plan

- The Fight for Canada

- Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

- North American Transportation Statistics Interchange

- Pacific Alliance

- Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)

- Free trade debate

- US public opinion on the North American Free Trade Agreement

- Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)

Notes

- ^ Calculated using UNDP data for the member states. If considered as a single entity, NAFTA would rank 23rd among the other countries.

References

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ^ "NAFTA's Economic Impact". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on July 21, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ a b "Poll Results | IGM Forum". www.igmchicago.org. March 13, 2012. Archived from the original on June 22, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ a b c Burfisher, Mary E; Robinson, Sherman; Thierfelder, Karen (February 1, 2001). "The Impact of NAFTA on the United States". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 15 (1): 125–44. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.516.6543. doi:10.1257/jep.15.1.125. ISSN 0895-3309. S2CID 154817996.

- ^ Hiltzik, Michael (January 30, 2017). "NAFTA doesn't count for much economically, but it's still a huge political football. Here's why". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ Rodrik, Dani (June 2017). "Populism and the Economics of Globalization". NBER Working Paper No. 23559. doi:10.3386/w23559.

- ^ a b c "Driving Home the Importance of NAFTA | Econofact". Econofact. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Eric Martin, Trump Killing Nafta Could Mean Big Unintended Consequences for the U.S. Archived February 19, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Bloomberg Business (October 1, 2015).

- ^ a b "Which American producers would suffer from ending NAFTA?". The Economist. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "Nafta withdrawal would hit US GDP without helping trade deficit – report". Financial Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022.

- ^ "United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement". USTR. Archived from the original on February 17, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ CBC News, "Mexico joins Canada, notifies U.S. it's ready to implement new NAFTA" 2020/04/04 Archived 2020-11-26 at the Wayback Machine accessed 06 April 2020

- ^ a b "North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- ^ Foreign Affairs and International trade Canada: Canada and the World: A History – 1984–1993: "Leap of Faith Archived October 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NAFTA: Final Text, Summary, Legislative History & Implementation Directory. New York: Oceana Publications. 1994. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-379-00835-7.

- ^ Labor Advisory Committee for Trade Negotiations and Trade Policy; established under the Trade Act of 1974.

- ^ Preliminary Report of the Labor Advisory Committee for Trade Negotiations and Trade Policy on the North American Free Trade Agreement Archived January 11, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, dated Sept. 16, 1992 (Washington, D.C.: Executive Office of the President, Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, 1992), i, 1.

- ^ For an overview of the process, see Noam Chomsky, "'Mandate for Change', or Business as Usual" Archived July 31, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, Z Magazine 6, no. 2 (February 1993), 41.

- ^ "H.R.3450 – North American Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act". December 8, 1993. Archived from the original on January 26, 2022. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ "Trump says many trade agreements are bad for Americans. The architects of NAFTA say he's wrong". Los Angeles Times. October 28, 2016. Archived from the original on August 15, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ Rudin, Ken (December 27, 2011). "Remembering Those Who Left Us In 2011". NPR.org. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ Luis Gutierrez on Why Rahm Emanuel Should Not Be Mayor Archived July 7, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Chicago Magazine, Carol Felsenthal, January 11, 2011. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ [9311150020_1_anti-nafta-forces-nafta-debate-undecided-house-members Gutierrez Resists Party Pressure, Vows He'll Vote Against Nafta], Chicago Tribune, November 13, 1993. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ Learning From The Experience Of NAFTA Labor And Environmental Governance Archived July 2, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Forbes Magazine, Mark Aspinwall, August 10, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ "Clinton Signs NAFTA – December 8, 1993". Miller Center. University of Virginia. Archived from the original on October 10, 2010. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ^ "NAFTA Timeline". Fina-nafi. Archived from the original on January 14, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ "YouTube". www.youtube.com. September 3, 2013. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ "Signing NaFTA". History Central. Archived from the original on March 23, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Decreto de promulgación del Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte [Decree of promulgation of the North American Free Trade Agreement] (PDF) (Decree) (in Spanish). Senate of the Republic (Mexico). December 20, 1993.

- ^ Floudas, Demetrius Andreas & Rojas, Luis Fernando; "Some Thoughts on NAFTA and Trade Integration in the American Continent" Archived 2017-10-21 at the Wayback Machine, 52 (2000) International Problems 371

- ^ Gantz, DA (1999). "Dispute Settlement Under the NAFTA and the WTO:Choice of Forum Opportunities and Risks for the NAFTA Parties". American University International Law Review. 14 (4): 1025–106.

- ^ "Pest Management Regulatory Agency". Health Canada. Branches and Agencies. nd. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ GPO, P.L. 103-182 Archived April 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Section 334

- ^ ML-497 Archived December 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine (March 1995), Docket No. RM 93-13C, Library of Congress Copyright Office

- ^ Carpentier, Chantal Line (December 1, 2006). "IngentaConnect NAFTA Commission for Environmental Cooperation: ongoing assessment". Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 24 (4): 259–272. doi:10.3152/147154606781765048.

- ^ Analytic Framework for Assessing the Environmental Effects of the North American Free Trade Agreement. Commission for Environmental Cooperation (1999)

- ^ "Trade and Environment in the Americas". Cec.org. Archived from the original on December 7, 2014. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ^ a b c McDowell, Manfred (1995). "NAFTA and the EC Social Dimension". Labor Studies Journal. 20 (1). Archived from the original on November 2, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Schliefer, Jonathan (December 1992). "What price economic growth?". The Atlantic Monthly: 114.

- ^ Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. National Administrative Office. "North American Agreement on Labor Cooperation: A Guide". dol.gov/agencies/ilab. U.S. Department of Labor. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "Accords fail to redraw battle lines over pact". The New York Times. August 14, 1993.

- ^ Witt, Matt (April 1990). "Don't trade on me: Mexican, U.S. and Canadian workers confront free trade". Dollars and Sense.

- ^ Compa, Lance (2001). "NAFTA's Labour Side Agr s Labour Side Agreement and International Labour Agreement and International Labour Solidarity" (PDF). core.ac.uk/. Cornell University ILR School. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "NAFTA, Chapter 11". Sice.oas.org. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ Government of Canada, Global Affairs Canada (July 31, 2002). "The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) – Chapter 11 – Investment". Archived from the original on January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ "'North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)', Public Citizen". Citizen.org. January 1, 1994. Archived from the original on March 10, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ Red Mexicana de Accion Frente al Libre Comercio. "NAFTA and the Mexican Environment". Archived from the original on December 16, 2000. Retrieved July 11, 2006.

- ^ "The Council of Canadians". Canadians.org. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ Commission for Environmental Cooperation. "The NAFTA environmental agreement: The Intersection of Trade and the Environment". Cec.org. Archived from the original on June 11, 2007. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ PEJ News. "Judge Rebuffs Challenge to NAFTA'S Chapter 11 Investor Claims Process". Pej.org. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ Ontario Court of Appeal (November 30, 2006). "Council of Canadians v. Canada (Attorney General), 2006 CanLII 40222 (ON CA)". CanLII. Archived from the original on March 9, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ "Arbitration award between Methanex Corporation and United States of America" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2007. (1.45 MB)

- ^ "Arbitration award between Metalclad Corporation and The United Mexican States" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2007. (120 KB)

- ^ Government of Canada, Foreign Affairs Trade and Development Canada (July 16, 2014). "Eli Lilly and Company v. Government of Canada". Archived from the original on January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c McKenna, Barrie (November 24, 2013). "Canada must learn from NAFTA legal battles". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ Government of Canada, Foreign Affairs Trade and Development Canada (December 5, 2012). "Lone Pine Resources Inc. v. Government of Canada". Archived from the original on January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Gray, Jeff (November 22, 2012). "Quebec's St. Lawrence fracking ban challenged under NAFTA". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ "Stock:Lone Pine Resources". Archived from the original on January 30, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c Millán, Juan. "North American Free Trade Agreement; Invitation for Applications for Inclusion on the Chapter 19 Roster" (PDF). Federal Register. Office of the United States Trade Representative. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 12, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ "NAFTA – Fast Facts: North American Free Trade Agreement". NAFTANow.org. April 4, 2012. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ Trefler, Daniel (September 2004). "The Long and Short of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement" (PDF). American Economic Review. 94 (4): 870–895. doi:10.1257/0002828042002633. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ Bernstein, William J. (May 16, 2009). A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World. Grove Press.

- ^ Romalis, John (July 12, 2007). "NAFTA's and CUSFTA's Impact on International Trade" (PDF). Review of Economics and Statistics. 89 (3): 416–35. doi:10.1162/rest.89.3.416. ISSN 0034-6535. S2CID 57562094. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 12, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Caliendo, Lorenzo; Parro, Fernando (January 1, 2015). "Estimates of the Trade and Welfare Effects of NAFTA". The Review of Economic Studies. 82 (1): 1–44. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.189.1365. doi:10.1093/restud/rdu035. ISSN 0034-6527. S2CID 20591348.

- ^ a b McBride, James; Sergie, Mohammed Aly (2017) [February 14, 2014]. "NAFTA's Economic Impact". Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) think tank. Archived from the original on May 16, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ "NAFTA and Climate Report 2018" (PDF). Sierra Club. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ a b Laxer, Gordon. "Escaping Mandatory Oil Exports: Why Canada needs to dump NAFTA's energy proportionality rule" (PDF). p. 28. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 27, 2018. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ a b "The coddling of the Canadian cow farmer". The Economist. Archived from the original on September 12, 2018. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- ^ Hufbauer, GC; Schott, JJ (2005). "NAFTA Revisited". Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Greening the Americas, Carolyn L. Deere (editor). MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- ^ Clark, Georgia Rae (2006). Mexican meat demand analysis: A post-NAFTA demand systems approach (MS thesis). Texas Tech University. hdl:2346/18215. Archived from the original on November 12, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Matt Nesvisky (September 2003). "What Happened to Wages in Mexico Since NAFTA?". nber.org. Archived from the original on November 7, 2023. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "NAFTA's Legacy for Mexico: Economic Displacement, Lower Wages for Most, Increased Migration". citizen.org. September 1, 2019. Archived from the original on November 7, 2023. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ Martha Rodriguez-Villalobos; Antonio Julián-Arias; Alejandro Cruz-Montaño (2019). "Effect of NAFTA on Mexico's Wage Inequality". International Journal of Economic Sciences. 8 (1): 131–149. doi:10.52950/ES.2019.8.1.009 (inactive November 1, 2024). Archived from the original on November 7, 2023. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "NAFTA, Corn, and Mexico's Agricultural Trade Liberalization" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 9, 2007. (152 KB) p. 4

- ^ Steven S. Zahniser & William T. Coyle, U.S.-Mexico Corn Trade During the NAFTA Era: New Twists to an Old Story Archived 2021-02-14 at the Wayback Machine, Outlook Report No. FDS04D01 (Economic Research Service/USDA, May 2004), 22 pp.

- ^ Becker, Elizabeth (August 27, 2003). "U.S. Corn Subsidies Said to Damage Mexico". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 21, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Ruiz Nápoles, Pablo. "El TLCAN y el balance comercial en México". Economía Informa. UNAM. 2003

- ^ H, Hanson, Gordon (March 9, 2007). "Globalization, Labor Income, and Poverty in Mexico". University of Chicago Press: 417–456. Archived from the original on January 29, 2018. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Prina, Silvia (August 2013). "Who Benefited More from the North American Free Trade Agreement: Small or Large Farmers? Evidence from Mexico". Review of Development Economics. 17 (3): 594–608. doi:10.1111/rode.12053. S2CID 154627747.

- ^ Prina, Silvia (January 2015). "Effects of Border Price Changes on Agricultural Wages and Employment in Mexico". Journal of International Development. 27 (1): 112–132. doi:10.1002/jid.2814.

- ^ O'Neil, Shannon (March 2013). "Mexico Makes It". Foreign Affairs. 92 (2). Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ Taylor, Guy (May 14, 2012). "NAFTA key to economic, social growth in Mexico". www.washingtontimes.com. The Washington Times. Archived from the original on March 30, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ "Economic Report of the exportations in the manufacturer industry" Consejo Nacional de Industria Maquiladora Manufacturera A.C. 2016

- ^ a b "The missing dimension in the NAFTA debate". Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 13, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ "Trump administration formally launches NAFTA renegotiation". Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 19, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ Frankel, Jeffrey (April 24, 2017). "How to Renegotiate NAFTA". Project Syndicate. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ Scott, Robert E. (July 21, 2014). "The effects of NAFTA on US trade, jobs, and investment, 1993â€"2013". Review of Keynesian Economics. 2 (4): 429–441. doi:10.4337/roke.2014.04.02. Archived from the original on July 23, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019 – via ideas.repec.org.

- ^ "The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 16, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "Contentious Nafta pact continues to generate a sparky debate". Financial Times. December 2, 2013. Archived from the original on May 7, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ a b "NAFTA's Economic Impact". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on February 4, 2017. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Porter, Eduardo (March 29, 2016). "Nafta May Have Saved Many Autoworkers' Jobs". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)". Office of the United States Trade Representative. Archived from the original on March 17, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2014.

- ^ Lavassani, Kayvan (June 2018). "Data Science Reveals NAFTA's Problem" (PDF). International Affairs Forum. No. June 2018. Center for International Relations. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 7, 2018. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ^ "Free Trade Agreement Helped U.S. Farmers". Archived 2009-01-29 at the Wayback Machine Newswise. Retrieved on June 12, 2008.

- ^ "North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) —". Archived from the original on November 25, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Villarreal, M. Angeles; Fergusson, Ian F. (May 24, 2017). The North American Free Trade Agreement (PDF). Congressional Research Service (CRS) (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 4, 2018. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ^ "North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) | United States Trade Representative". ustr.gov. Archived from the original on May 8, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- ^ a b DeLong, J. Bradford. "NAFTA and other trade deals have not gutted American manufacturing – period". Vox. Archived from the original on June 18, 2017. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ "What did NAFTA really do?". Dani Rodrik's weblog. Archived from the original on February 8, 2017. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ Faux, Jeff (December 9, 2013). "NAFTA's Impact on U.S. Workers". Economic Policy Institute. Archived from the original on April 22, 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Economy Lost Nearly 700,000 Jobs Because Of NAFTA, EPI Says". The Huffington Post. July 12, 2011. Archived from the original on January 18, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ Long, Heather (February 16, 2017). "U.S. auto workers hate NAFTA ... but love robots". CNNMoney. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

The problem, they argue, is that machines took over. One study by Ball State University says 87% of American manufacturing jobs have been lost to robots. Only 13% have disappeared because of trade ... But workers in Michigan think the experts have it wrong.

- ^ Cherniwchan, Jevan (2017). "Trade Liberalization and the Environment: Evidence from NAFTA and U.S. Manufacturing". Journal of International Economics. 105: 130–49. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2017.01.005.

- ^ a b c "Environmental Damages Underscore Risks of Unfair Trade". Sierraclub.org. Archived from the original on March 15, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ "IngentaConnect NAFTA Commission for Environmental Cooperation: ongoing assessment of trade liberalization in North America". Ingentaconnect.com. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ^ Kenneth A. Reinert and David W. Roland-Holst The Industrial Pollution Impacts of NAFTA: Some Preliminary Results. Commission for Environmental Cooperation (November 2000)

- ^ "DHS Yearbook 2006. Supplemental Table 1: Nonimmigrant Admissions (I-94 Only) by Class of Admission and Country of Citizenship: Fiscal Year 2006". Archived from the original on February 28, 2011. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Jones, Reese. Borders & Walls: Do Barriers Deter Unauthorized Migration. Migration Policy Institute. web page [1] Archived November 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine October 5, 2016.

- ^ Bacon, David (October 11, 2014). "Globalization and NAFTA Caused Migration from Mexico". Political Research Associates. Archived from the original on April 9, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ Facts and Figures 2006 Immigration Overview: Temporary Residents Archived February 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine (Citizenship and Immigration Canada)

- ^ "Facts and Figures 2006 – Immigration Overview: Permanent and Temporary Residents". Cic.gc.ca. June 29, 2007. Archived from the original on August 22, 2008. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ^ "THE 1992 CAMPAIGN; Transcript of 2d TV Debate Between Bush, Clinton and Perot". The New York Times. October 16, 1992. Archived from the original on December 29, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ "Notice of Arbitration" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2007. (1.71 MB), 'Ethyl Corporation vs. Government of Canada'

- ^ "Agreement on Internal Trade" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 22, 2006. (118 KB)

- ^ "Dispute Settlement". Dfait-maeci.gc.ca. October 15, 2010. Archived from the original on January 15, 2008. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ "MMT: the controversy over this fuel additive continues". canadiandriver.com. Archived from the original on April 24, 2008. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ softwood Lumber Archived June 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Statement from USTR Spokesperson Neena Moorjani Regarding the NAFTA Extraordinary Challenge Committee decision in Softwood Lumber". Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ "Tembec, Inc vs. United States" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2006. Retrieved August 9, 2006. (193 KB)

- ^ "Statement by USTR Spokesman Stephen Norton Regarding CIT Lumber Ruling". Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Canada, Global Affairs; Canada, Affaires mondiales (June 26, 2013). "Global Affairs Canada". Archived from the original on August 2, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ Fiess, Norbert; Daniel Lederman (November 24, 2004). "Mexican Corn: The Effects of NAFTA" (PDF). Trade Note. 18. The World Bank Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2007. Retrieved March 12, 2007.

- ^ Subcomandante Marcos, Ziga Voa! 10 Years of the Zapatista Uprising. AK Press 2004

- ^ Politico Staff (September 27, 2016). "Full transcript: First 2016 presidential debate". Politico. Archived from the original on September 30, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- ^ Jill Colvin, Trump: NAFTA trade deal a 'disaster,' says he'd 'break' it Archived 2016-03-14 at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press (September 25, 2015).

- ^ Mark Thoma, Is Donald Trump right to call NAFTA a "disaster"? Archived February 19, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, CBS News (October 5, 2015).

- ^ a b Gonzales, Lilia (November 14, 2016). "El Economista". Archived from the original on November 16, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ Eric Martin, Trump Killing NAFTA Could Mean Big Unintended Consequences for the U.S. Archived February 19, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Bloomberg Business (October 1, 2015).

- ^ "Sen. Bernie Sanders on taxes, trade agreements and Islamic State". PBS. May 18, 2015. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2015. (transcript of interview with Judy Woodruff)

- ^ Sanders, Bernie (May 21, 2015). "The TPP Must Be Defeated". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- ^ Will Cabaniss for Punditfact. September 2, 2015 How Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton differ on the Trans-Pacific Partnership Archived December 20, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Canada, Mexico talked before making NAFTA overture to Trump". Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ^ Irwin, Neil (January 25, 2017). "What Is Nafta, and How Might Trump Change It?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 28, 2017. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Rappeport, Alan (July 17, 2017). "U.S. Calls for 'Much Better Deal' in Nafta Overhaul Plan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 18, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ "U.S. makes lower trade deficit top priority in NAFTA talks". Reuters. July 18, 2017. Archived from the original on September 14, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Alexander Panetta (November 1, 2017). "U.S. pro-NAFTA campaign ramps up to defend deal: Concerns in Congress heighten over 'potential catastrophe' from withdrawal". Vancouver Sun. Canadian Press.

- ^ Laura Stone; Robert Fife (October 13, 2017). "Canada, Mexico vow to remain at NAFTA negotiating table". The Globe and Mail. p. A1.

- ^ Gollom, Mark (August 30, 2018). "Canada had little choice but to play it cool in NAFTA talks, trade experts say". CBC News. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

Charm offensive hadn't worked with U.S., so there was not much Trudeau could have done to save NAFTA, say some

- ^ Lee, Don (August 27, 2018). "U.S. and Mexico strike preliminary accord on NAFTA; Canada expected to return to bargaining table". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ "Trump Reaches Revised Trade Deal With Mexico, Threatening to Leave Out Canada". The New York Times. August 27, 2018. Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ a b "NAFTA's sticking points: Key hurdles to clear on the way to a deal". The Ottawa Citizen via Canadian Press. Ottawa, Ontario. August 30, 2018. Archived from the original on September 3, 2018. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ^ a b c "America's deal with Mexico will make NAFTA worse". The Economist. Going south. August 30, 2018. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

Its costly new regulations result from flawed economic logic