Mutualism (economic theory)

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

Mutualism is an anarchist school of thought and anti-capitalist market[1] socialist[2] economic theory that advocates for workers' control of the means of production, a market economy made up of individual artisans and workers' cooperatives, and occupation and use property rights. As proponents of the labour theory of value and labour theory of property, mutualists oppose all forms of economic rent, profit and non-nominal interest, which they see as relying on the exploitation of labour. Mutualists seek to construct an economy without capital accumulation or concentration of land ownership. They also encourage the establishment of workers' self-management, which they propose could be supported through the issuance of mutual credit by mutual banks, with the aim of creating a federal society.

Mutualism has its roots in the utopian socialism of Robert Owen and Charles Fourier. It first developed a practical expression in Josiah Warren's community experiments in the United States, which he established according to the principles of equitable commerce based on a system of labor notes. Mutualism was first formulated into a comprehensive economic theory by the French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who proposed the abolition of unequal exchange and the establishment of a new economic system based on reciprocity. In order to establish such a system, he proposed the creation of a "People's Bank" that could issue mutual credit to workers and eventually replace the state; although his own attempts to establish such a system were foiled by the 1851 French coup d'état.

After Proudhon's death, mutualism lost its popularity within the European anarchist movement and was eventually redefined in counterposition to anarchist communism. Proudhon's thought was instead taken up by American individualists, who came to be closely identified with mutualist economics. Joshua K. Ingalls and William Batchelder Greene developed on mutualist theories of value, property and mutual credit, while Benjamin Tucker elaborated a mutualist critique of capitalism. The American mutualist Dyer Lum attempted to bridge the divide between communist and individualist anarchists, but many of the latter camp eventually split from the anarchist movement and embraced right-wing politics.

Mutualist ideas were later implemented in local exchange trading systems and alternative currency models, but the tendency itself fell out of the popular consciousness during the 20th century. The advent of the internet generated a revived interest in mutualist economics, particularly after the publication of new works on the subject by American libertarian theorist Kevin Carson.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]According to Peter Kropotkin, the origins of mutualism lay in the events of the French Revolution, particularly in the federalist and directly democratic structure of the Paris Commune.[3] The foundations of mutualist economic theory lay in the radicalism of English socialist Thomas Spence. Drawing from the Bible, as well as the liberal works of John Locke and James Harrington, Spence called for the abolition of private property, and for the workers' control of production through workers' cooperatives.[4] The term "mutualism" was first used during the 1820s; originally defined synonymously with terms such as "mutual aid, reciprocity and fair play".[5] In 1822, French utopian philosopher Charles Fourier used the term "convergent compound mutualism" (French: mutualisme composé convergent), in order to describe a form of progressive education that adapted the Monitorial System of pupil-teachers.[6]

Owenism and Josiah Warren

[edit]

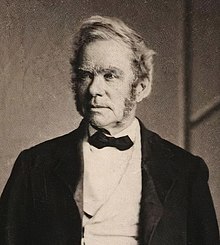

Thomas Spence's mutualist platform was taken up by Robert Owen, with Owenism becoming a pioneering force in the history of the cooperative movement.[7] By 1826, the term "mutualism" was being used by members of Owen's utopian community of New Harmony, Indiana, in order to propose a more decentralised and libertarian project.[6] The following year, Josiah Warren left New Harmony and established the Cincinnati Time Store, which was based on his ideas of "equitable commerce".[8] This system set cost as the limit of price and established exchange based on labor notes.[9] In keeping with his mutualist principles, Warren refused to substantially grow his business, maintaining the equal exchange between shopkeeper and customer.[10] He hoped the shop would eventually be the nucleus for the establishment of a "mutualist village".[11]

After running it for three years,[12] in May 1830, Warren decided to liquidate the Time Store in an attempt to pursue his plan of building a mutualist village in Ohio.[13] This caught the attention of Robert Owen, who proposed that they instead build a mutualist community in New York, but this project never met fruition.[14] Warren made the decision to delay the establishment of his mutualist colony until 1833.[15] He spent the preceding years sketching out the voluntarist structure of the planned community, together with other prospective members.[16] They established their anarchist community in Tuscarawas County, Ohio, but it was short-lived, as an influenza epidemic forced them to abandon the village by 1835.[17] Warren returned to New Harmony, where he established another Time Store, but he received little support from other community members and shut it down in March 1844.[18] Nevertheless, his mutualist ideas were still taken up by other radicals of the period, with George Henry Evans and his Land Reform Association championing mutualist arguments against the concentration of land ownership.[19]

Warren returned to Ohio, where he founded the mutualist community of Utopia in 1847, taking over from an earlier Fourierist community that had established the settlement.[20] The community adopted labor notes as its currency and committed itself to an economy of equitable commerce, with cost as the limit of price.[21] Utopia grew to about one hundred residents and established various enterprises, demonstrating to Warren the potential of his economic principles of decentralisation.[22] By the 1850s, Warren himself had moved on from Ohio and established the Utopian Community of Modern Times on Long Island, New York,[23] but his mutualist experiments would decline with the outbreak of the American Civil War.[24] Warren's mutualist communities of Utopia and Modern Times ultimately lasted for twenty years,[12] eventually evolving into traditional villages with only minor mutualist tendencies.[25]

Formulation by Proudhon

[edit]

The term "mutualist" was adopted in 1828 by the canuts of Lyon, who went on to lead a series of revolts throughout the 1830s.[6] At this same time, the young French activist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was first being drawn towards Fourier's utopian socialism; by 1843, Proudhon had joined the Mutualists in Lyon.[26] The adoption of the term "mutualist" by Proudhon and his development of anarchism would result in a shift of its meaning and understanding.[27]

Proudhon held "mutuality" (or "exchange in kind") to be a core part of his economic theory.[28] In his System of Economic Contradictions (1846), Proudhon described mutuality as a synthesis of "private property and collective ownership".[29] The mutualist principle of reciprocity provided the basis for all its proposed institutions,[30] including mutual aid, mutual credit and mutual insurance. Proudhon considered the perfect expression of mutuality to be a synallagmatic contract of equal exchange between equal individuals.[31] Proudhon considered the unequal exchange to be at the root of the exploitation of labour and believed that a truly free market ought to be built on reciprocity, without coercion.[32] He concluded that under such conditions, commerce would progress towards equal exchange, where the value of a product or service reflects only the cost of its production.[33] He envisioned the eventual "withering away of the state" and its replacement with a system of economic contracts between individuals and collectives.[34]

Proudhon claimed that private property constituted a form of robbery, as proprietors used their title to extract labour-value from others,[35] or as he characterised it: "the proprietor reaps where [they] did not sow".[36] To Proudhon, wage labour represented the enclosure of the value of collective production, with the capitalist collecting economic rent from their workers in the form of profit.[37] Proudhon's anti-capitalist economic theories stood in sharp contrast to liberal economists of the time, such as Frédéric Bastiat and Henry Charles Carey, who argued in defense of landlords and capitalists from the claims of workers.[38] Proudhon claimed that landlords and capitalists contributed nothing to production, and that their only claim to the contrary was by not impeding access to the means of production.[39]

In the wake of the French Revolution of 1848, Proudhon began elaborating his proposal for a "Bank of the People".[40] He thought such a bank could guarantee mutual credit to all workers, enabling them bring the product of their labour under the collective ownership of all that participated in production.[41] After he was elected to the Constituent Assembly, Proudhon lobbied for the transformation of the Bank of France into such a "Bank of the People"; he proposed that a 2-3% interest rate would be enough to cover all public expenses and would allow for the abolition of taxation. Proudhon's "Bank of the People" was officially incorporated but was never able to establish itself in practice, as Proudhon was arrested and imprisoned following the rise to power of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte.[42] In his final attempt at writing a comprehensive mutualist programme, The Political Capacity of the Working Classes (1865), Proudhon proposed the establishment of a "mutualist system" of workers' self-management.[43]

Anarchism and the IWA

[edit]During the early 1860s, the French anarchist movement first began to develop an organised expression, establishing trade unions and mutual credit systems inspired by Proudhon's mutualist theories.[44] Towards the end of his life, Proudhon himself had grown more cautious of using the term "anarchist" and instead referred to himself as a "federalist"; his followers also eschewed the "anarchist" label, instead calling themselves "mutualists" after his principle of mutual exchange.[45] After Proudhon's death in 1865,[46] his mutualist followers helped establish the International Workingmen's Association (IWA).[47]

In the early years of the IWA, the organisation was largely mutualist,[48] as exemplified by its contractual demands during its 1866 Geneva Congress and 1867 Lausanne Congress. But in the following years, French mutualists began to lose control over the organisation to Russian and German communists based in Belgium,[43] and mutualism was gradually overshadowed by other anarchist schools of thought.[49] By the end of the 1860s, the French section of the IWA was already shifting away from mutualism, with Eugène Varlin and Benoît Malon convincing it to adopt Mikhail Bakunin's platform of collectivism;[44] Bakunin himself held his collectivist theories to be "Proudhonism, greatly developed and taken to its ultimate conclusion".[50]

Although inspired by Proudhon's arguments for federalism, Bakunin broke from his mutualist economics and argued instead for the common ownership of land.[51] By the 1870s, as divisions between the Marxists and the anti-authoritarians in the IWA grew sharper, Proudhonian mutualism gradually lost its remaining influence; although it continued to see minor developments by collectivists such as César De Paepe and Claude Pelletier,[52] as well as in the programme of the Paris Commune of 1871.[53] When the IWA finally split, members of the anti-authoritarian faction slowly adopted "anarchism" as the label for their philosophy.[54]

Following Bakunin's death in 1876,[55] the Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin had taken anarchist philosophy beyond both Proudhon's mutualism and Bakunin's collectivism.[56] He argued instead for anarchist communism, in which resources are distributed "from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs."[57] This quickly became the dominant form of anarchism,[55] and by the 1880s, mutualism was slowly defined in opposition to anarchist communism.[58] Mutualism was redefined as a non-communist form of anarchism, due to its emphasis on reciprocity, reformism and commerce. As a result, different tendencies and interpretations of mutualism started to emerge.[55]

Development by American individualists

[edit]Warren's mutualist experiments, which inspired the American individualism of Lysander Spooner and Stephen Pearl Andrews,[59] laid a foundation for the introduction of Proudhonian mutualism to the country.[60] Warren himself was later retroactively labelled a "mutualist" by the individualists of this period, who were inspired by his system of "equitable commerce".[61] American newspaper editor William Henry Channing synthesised Proudhon's mutualism with Fourierism and Christian socialism, conceiving of "the coming era of mutualism" in millenarian terms.[62] Proudhonian mutualism was later discussed in articles by a number of American utopian theorists, including Francis George Shaw, Albert Brisbane and Charles Anderson Dana.[63]

Theoretical developments

[edit]

Two of the most important figures of this period were Joshua K. Ingalls and William Batchelder Greene,[64] who were inspired by Proudhon's mutualist ideas as elaborated by Dana,[65] synthesising it with American individualist traditions pioneered by Warren.[66] Ingalls was a vocal proponent of the labour theory of value and an advocate of workers receiving the full product of their labor.[67] He also argued against the concentration of land ownership, which he believed to be the principal source of social inequality,[68] and instead called for the institution of occupancy-and-use property rights.[69]

Drawing from Esoteric Christianity, Greene presented Proudhonian mutualism as a successor to Christianity, describing it as "the religion of the coming age."[63] Greene proposed the establishment of mutual banks,[70] which would issue loans at a nominal interest rate.[71] He believed these could outcompete the high interest rates charged by commercial banks and lead to wages rising to the "full value of the work done".[71] Greene's model for a free price system, which he argued would trend towards labor-value as economic rents and social privileges were abolished, represented a break from Owen and Warren's "labor for labor" theory of exchange.[72] Greene argued that the fruit of all human labors was a product, not only of individual effort, but also of social circumstances that aided them in that effort.[73]

In 1869, Ezra and Angela Heywood established the New England Labor Reform League (NELRL), which published the individualist anarchist magazine The Word and widely distributed the works of American mutualists such as Warren and Greene, who were also members of the organisation.[61] From 1872 to 1876, the NELRL attempted to lobby the Massachusetts General Court to establish a mutual bank, but they were ultimately unsuccessful,[74] convincing them that state legislatures had already undergone regulatory capture by capitalists.[72]

Anti-capitalist critique

[edit]

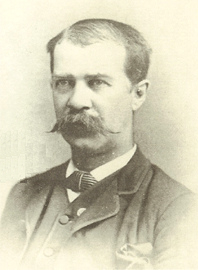

Inspired by the older mutualists within the NELRL, the young League member Benjamin Tucker quickly rose to prominence as one of the leading figures of individualist anarchism in the United States.[61] Tucker integrated the earlier iterations of mutualism into a single ideological doctrine,[75] adopting Greene's ideas on mutual banking and synthesising Proudhonian mutualism with the American individualist tradition of Warren and Spooner.[76] Through his magazine Liberty, which he established in 1881, he contributed to the development of anarchist political thought.[77]

Drawing from the mutualism of Warren and Proudhon, he argued that the exploitation of labour derived from authority of the state,[78] which collaborated with capitalists in order to extract labour value in the form of "interest, rent and profit".[79] In order to combat coercive practices that allowed the proliferation of wealth and privilege, Tucker proposed the establishment of a "free market of anarchistic socialism", in which all forms of monopoly were abolished.[80] Tucker derided profit as antithetical to free competition and criticised capitalism for "abolishing the free market", arguing that a truly free market was governed only by the cost of production. [81] At the center of his anti-capitalist critique were what he called the "Four Monopolies":[82] that of money, land, tariffs and patents.[83]

While Tucker was intensely critical of capitalism, he was uninterested in speculating on the makeup of a future mutualist society. This was eventually taken up by John Beverley Robinson, who built on Tucker's critique to advocate for cooperative economics and mutual aid.[84] Tucker's followers dedicated themselves to elaborating mutualist projects, with Alfred B. Westrup, Herman Kuehn and Clarence Lee Swartz all writing extensively on the subject of mutual credit.[85]

Divisions and decline

[edit]

By the beginning of the Gilded Age, Proudhonian mutualism was firmly identified with American individualism,[86] while Tucker's followers came to define themselves in opposition to anarchist communism.[58] Although Tucker himself didn't make the distinction, anarchists such as Henry Seymour increasingly contrasted mutualism against communism, with mutualism eventually being used to refer to "non-communist anarchism".[85] One of Tucker's disciples, Dyer Lum, attempted to bridge the divide between the American individualists and the growing labour movement, which was developing sympathies for social anarchism.[87] In the 1880s, Lum joined the International Working People's Association (IWPA), in which he developed a laissez-faire analysis of "wage slavery" that proposed a form of occupation and use property rights and a mutual banking system.[88]

Over the years, Lum worked to develop ties between different radical tendencies, hoping to create a "pluralistic anarchistic coalition" capable of advancing a social revolution.[89] By the time of the Haymarket affair, Lum had aligned with the IWPA's view of labor unions as a means to both combat the exploitation of labour and to prefigure a future free association of producers. In the 1890s, Lum joined the American Federation of Labor (AFL), within which he introduced workers' to mutualist ideas on banking, land reform and cooperativism through his pamphlet The Economics of Anarchy.[90] Lum was instrumental in synthesising mutualist economics with populist politics into a "uniquely American ideology",[91] one which was taken up by the American individualist Voltairine De Cleyre.[92]

But factional divides also began to exacerbate at this time, as Tucker's individualist group in Boston and immigrant revolutionary socialists in Chicago split into opposing camps, while Lum attempting to mend relations between the two.[90] Lum and Decleyre together developed a perspective of "anarchism without adjectives", in an attempt to overcome the ongoing feud between individualist and communist anarchists.[93] But eventually the split drove many of Tucker's disciples away from the anarchist movement and towards right-wing politics, with some like Clarence Lee Swartz coming to embrace capitalism and setting the groundwork for modern American libertarianism.[94]

Contemporary developments

[edit]

During the early 20th century, mutualist concepts were developed by the economists Ralph Borsodi and Silvio Gesell; while mutualist ideas were implemented within local exchange trading systems and by models of alternative currency.[46] Gustav Landauer, who became a leading figure in the Bavarian Soviet Republic during the German Revolution of 1918–1919, adopted a mutualist programme of mutual credit, equal exchange and usufruct property rights.[95] Some anarchist theorists of the late 20th century were also inspired by mutualism, including American social critic Paul Goodman, Italian essayist C. George Benello, British social historian Colin Ward,[46] and American philosopher Peter Lamborn Wilson.[96] In order to provide an alternative to the dominant anarchist schools of thought, Larry Gambone attempted to revive the mutualist movement; he established the Voluntary Cooperation Movement, which managed to recruit the British anarchist Jonathan Simcock and the American individualist Joe Peacott, but it was short-lived.[97]

By the end of the 20th century, mutualism had largely fallen out of the popular consciousness, only experiencing a revival in interest when the internet improved public access to old texts. American libertarian theorist Kevin Carson was central to the renewed interest in the subject, self-publishing a series of works on mutualism. Carson's Studies in Mutualist Political Economy proposed a synthesis of Austrian and Marxian economics, developing a form of "free-market anti-capitalism" based on Tucker's conception of mutualism. Interest in Proudhon's works was also renewed during the 21st century, with many of his texts being published by the Proudhon Library and compiled into the collection Property is Theft.[98]

Theory

[edit]The primary aspects of mutualism are free association, free banking, reciprocity in the form of mutual aid, workplace democracy, workers' self-management, gradualism and dual power. Mutualism is often described by its proponents as advocating an anti-capitalist free market. Mutualists argue that most of the economic problems associated with capitalism each amount to a violation of the cost principle, or as Josiah Warren interchangeably said, cost the limit of price. It was inspired by the labour theory of value, which was popularized—although not invented—by Adam Smith in 1776 (Proudhon mentioned Smith as an inspiration). The labor theory of value holds that the actual price of a thing (or the true cost) is the amount of labor undertaken to produce it. In Warren's terms of his cost the limit of price theory, cost should be the limit of price, with cost referring to the amount of labour required to produce a good or service. Anyone who sells goods should charge no more than the cost to himself of acquiring these goods.[99]

Contract and federation

[edit]Mutualism holds that producers should exchange their goods at cost-value using contract systems. While Proudhon's early definitions of cost-value were based on fixed assumptions about the value of labour hours, he later redefined cost-value to include other factors such as the labour intensity, the nature of the work involved, etc. He also expanded his notions of contract into expanded notions of federation.[99]

Free association

[edit]Mutualists argue that association is only necessary where there is an organic combination of forces. An operation requires specialization and many different workers performing tasks to complete a unified product, i.e. a factory. In this situation, workers are inherently dependent on each other; without association, they are related as subordinate and superior, master and wage-slave. An operation that an individual can perform without the help of specialized workers does not require association. Proudhon argued that peasants do not require societal form and only feigned association for solidarity in abolishing rents, buying clubs, etc. He recognized that their work is inherently sovereign and free.[99]

For Proudhon, mutualism involved creating industrial democracy. In this system, workplaces would be "handed over to democratically organised workers' associations. ... We want these associations to be models for agriculture, industry and trade, the pioneering core of that vast federation of companies and societies woven into the common cloth of the democratic social Republic".[100]

K. Steven Vincent notes in his in-depth analysis of this aspect of Proudhon's ideas that "Proudhon consistently advanced a program of industrial democracy which would return control and direction of the economy to the workers". For Proudhon, "strong workers' associations ... would enable the workers to determine jointly by election how the enterprise was to be directed and operated on a day-to-day basis".[101]

Mutual credit

[edit]Mutualists support mutual credit and argue that free banking should be taken back by the people to establish systems of free credit. They contend that banks have a monopoly on credit, just as capitalists have a monopoly on the means of production and landlords have a land monopoly. Banks create money by lending out deposits that do not belong to them and then charging interest on the difference. Mutualists argue that by establishing a democratically run mutual savings bank or credit union, it would be possible to issue free credit so that money could be created for the participants' benefit rather than the bankers' benefit. Individualist anarchists noted for their detailed views on mutualist banking include Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and William Batchelder Greene.[99]

Property

[edit]Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was an anarchist and socialist philosopher who articulated thoughts on the nature of property. He claimed that "property is theft", "property is liberty", and "property is impossible". According to Colin Ward, Proudhon did not see a contradiction between these slogans. This was because Proudhon distinguished between what he considered to be two distinct forms of property often bound up in a single label. To the mutualist, this is the distinction between property created by coercion and property created by labour. Property is theft "when it is related to a landowner or capitalist whose ownership is derived from conquest or exploitation and [is] only maintained through the state, property laws, police, and an army". Property is freedom for "the peasant or artisan family [who have] a natural right to a home, land [they may] cultivate, ... to tools of a trade" and the fruits of that cultivation—but not to ownership or control of the lands and lives of others. The former is considered illegitimate property, while the latter is legitimate property.[102]

In What Is Mutualism?, Clarence Lee Swartz wrote:

It is, therefore, one of the purposes of Mutualists, not only to awaken in the people the appreciation of and desire for freedom, but also to arouse in them a determination to abolish the legal restrictions now placed upon non-invasive human activities and to institute, through purely voluntary associations, such measures as will liberate all of us from the exactions of privilege and the power of concentrated capital.[103]

Swartz also argued that mutualism differs from anarcho-communism and other collectivist philosophies by its support of private property, writing: "One of the tests of any reform movement with regard to personal liberty is this: Will the movement prohibit or abolish private property? If it does, it is an enemy of liberty. For one of the most important criteria of freedom is the right to private property in the products of ones labor. State Socialists, Communists, Syndicalists and Communist-Anarchists deny private property."[104] However, Proudhon warned that a society with private property would lead to statist relations between people.[103] Unlike capitalist private-property supporters, Proudhon stressed equality. He thought that all workers should own property and have access to capital, stressing that in every cooperative, "every worker employed in the association [must have] an undivided share in the property of the company".[105]

Usufruct

[edit]Mutualists believe that land should not be a commodity to be bought and sold, advocating for conditional titles to land based on occupancy and use norms. Mutualists argue whether an individual has a legitimate claim to land ownership if he is not currently using it but has already incorporated his labour into it. All mutualists agree that everything produced by human labour and machines can be owned as personal property. Mutualists reject the idea of non-personal property and non-proviso Lockean sticky property. Any property obtained through violence, bought with money gained through exploitation, or bought with money that was gained violating usufruct property norms is considered illegitimate.[106][99]

Criticism

[edit]In Europe, a contemporary critic of Proudhon was the early libertarian communist Joseph Déjacque. Unlike and against Proudhon, he argued that "it is not the product of his or her labor that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature".[107][108]

One area of disagreement between anarcho-communists and mutualists stems from Proudhon's alleged advocacy of labour vouchers to compensate individuals for their labour and markets or artificial markets for goods and services. However, the persistent claim that Proudhon proposed a labour currency has been challenged as a misunderstanding or misrepresentation.[109] Like other anarcho-communists, Peter Kropotkin advocated the abolition of labour remuneration and questioned, "how can this new form of wages, the labor note, be sanctioned by those who admit that houses, fields, mills are no longer private property, that they belong to the commune or the nation?"[110] According to George Woodcock, Kropotkin believed that a wage system, whether "administered by Banks of the People or by workers' associations through labor cheques", is a form of compulsion.[111]

Collectivist anarchist Mikhail Bakunin was an adamant critic of Proudhonian mutualism as well,[112] stating: "How ridiculous are the ideas of the individualists of the Jean Jacques Rousseau school and of the Proudhonian mutualists who conceive society as the result of the free contract of individuals absolutely independent of one another and entering into mutual relations only because of the convention drawn up among men. As if these men had dropped from the skies, bringing with them speech, will, original thought, and as if they were alien to anything of the earth, that is, anything having social origin".[113]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Chartier, Gary; Johnson, Charles W. (2011). Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty. Brooklyn: Minor Compositions/Autonomedia. pp 5. “…’mutualism’ is now retrospectively used, in the twenty-first century, to refer to most anti-capitalist market anarchists…”

- ^ Fraser, Elizabeth. Selected Writings of P. J. Proudhon. Anchor Books: USA. 1969. pp 23. “Proudhon’s ’mutualism’ is a socialism of credit and exchange.”

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 431–432.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 83.

- ^ Wilbur 2019, p. 213.

- ^ a b c Wilbur 2019, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 385, 497–498; Martin 1970, pp. 15–16; Wilbur 2019, p. 215.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 385; Wilbur 2019, p. 220.

- ^ Martin 1970, p. 20.

- ^ Martin 1970, p. 16.

- ^ a b North 2007, p. 50.

- ^ Martin 1970, p. 22.

- ^ Martin 1970, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Martin 1970, p. 31.

- ^ Martin 1970, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 385–386; Martin 1970, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Martin 1970, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Martin 1970, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 385–386; Martin 1970, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Martin 1970, pp. 59–62.

- ^ Martin 1970, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 386; Martin 1970, p. 63.

- ^ Martin 1970, p. 63.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 386.

- ^ Wilbur 2019, p. 215.

- ^ Wilbur 2019, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 91; Wilbur 2019, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 91.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 91–92; Wilbur 2019, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 92.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 93; Vest 2020, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 93–94; Vest 2020, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 94.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 96.

- ^ North 2007, p. 50; Wilbur 2019, p. 216.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 94–95; North 2007, p. 50; Wilbur 2019, p. 216.

- ^ North 2007, pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b Wilbur 2019, p. 216.

- ^ a b Marshall 1993, p. 435.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 434.

- ^ a b c Shantz 2009, p. 2.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 431; Shantz 2009, p. 2; Wilbur 2019, p. 216.

- ^ Shantz 2009, p. 2; Wilbur 2019, p. 216.

- ^ North 2007, p. 51; Shantz 2009, p. 2.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 434; Wilbur 2019, p. 217.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 275.

- ^ Wilbur 2019, p. 217.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 435; Shantz 2009, p. 2.

- ^ Wilbur 2019, pp. 217–218.

- ^ a b c Wilbur 2019, p. 214.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 327.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 327; Wilbur 2019, p. 218.

- ^ a b Wilbur 2019, p. 218.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 91; Marshall 1993, p. 387.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 387.

- ^ a b c Wilbur 2019, p. 220.

- ^ Wilbur 2019, pp. 218–219.

- ^ a b Wilbur 2019, p. 219.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 102; Wilbur 2019, p. 219.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 103; Marshall 1993, p. 236; Vest 2020, p. 114.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 387, 497–498; Vest 2020, p. 115.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 103; Martin 1970, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 103; Martin 1970, pp. 140–142.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 103; Martin 1970, pp. 144, 148–149.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 102; Wilbur 2019, p. 219; Vest 2020, p. 114.

- ^ a b Carson 2018, p. 102.

- ^ a b Carson 2018, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Vest 2020, p. 115.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 102; Vest 2020, p. 114.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 104.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 104; Vest 2020, pp. 114–115; Wilbur 2019, p. 220.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 104–105; Vest 2020, p. 115; Wilbur 2019, p. 220.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 105; Wilbur 2019, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 105.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 107–108; Vest 2020, p. 115.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 108.

- ^ a b Wilbur 2019, p. 221.

- ^ Vest 2020, pp. 114–115; Wilbur 2019, p. 221.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 109.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b Carson 2018, p. 110.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 111.

- ^ Carson 2018, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 112.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 413–414.

- ^ Marshall 1993, p. 682; Shantz 2009, p. 2.

- ^ Carson 2018, p. 116.

- ^ Wilbur 2019, p. 222.

- ^ a b c d e Wilbur, Shawn P. (2018). "Mutualism". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl. The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. Springer. pp. 213–224. ISBN 9783319756202.

- ^ Guerin, Daniel, ed. (2006) No Gods, No Masters. 1. Oakland: AK Press. p. 62. ISBN 9781904859253.

- ^ Vincent, K. Steven (1984). Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and the Rise of French Republican Socialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 156, 230. ISBN 9780195034134.

- ^ Ward, Colin (2004). Anarchism: A Very Short Introduction.

- ^ a b Bojicic, Savo (2010). America America or Is It? Bloomington: AuthorHouse. p. 369. ISBN 9781452034355.

- ^ Weisbord, Albert (1937). The Conquest of Power: Liberalism, Anarchism, Syndicalism, Socialism, Fascism, and Communism. I. New York: Covici-Friede. p. 235.

- ^ Quoted by James J. Martin. Men Against the State. p. 223.

- ^ Martin, James J. (1970). Men Against the State. Colorado Springs: Ralph Myles Publisher. pp. viii, ix, 209. ISBN 9780879260064

- ^ Graham, Robert (2005). Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas. Black Rose Books. ISBN 978-1-55164-251-2.

- ^ Pengam, Alain. "Anarchist-Communism". According to Pengam, Déjacque criticized Proudhon as far as "the Proudhonist version of Ricardian socialism, centred on the reward of labour power and the problem of exchange value. In his polemic with Proudhon on women's emancipation, Déjacque urged Proudhon to push on 'as far as the abolition of the contract, the abolition not only of the sword and of capital, but of property and authority in all their forms,' and refuted the commercial and wages logic of the demand for a 'fair reward' for 'labour' (labour power). Déjacque asked: 'Am I thus right to want, as with the system of contracts, to measure out to each—according to their accidental capacity to produce—what they are entitled to?' The answer given by Déjacque to this question is unambiguous: 'it is not the product of his or her labour that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature.' [...] For Déjacque, on the other hand, the communal state of affairs—the phalanstery 'without any hierarchy, without any authority' except that of the 'statistics book'—corresponded to 'natural exchange,' i.e. to the 'unlimited freedom of all production and consumption; the abolition of any sign of agricultural, individual, artistic or scientific property; the destruction of any individual holding of the products of work; the demonarchisation and the demonetarisation of manual and intellectual capital as well as capital in instruments, commerce and buildings."

- ^ McKay, Iain (Spring 2017). "Proudhon's Constituted Value and the Myth of Labour Notes". Anarchist Studies. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (1920). "The Wage System". Freedom Pamphlets (1). Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Woodcock, George (2004). Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Broadview Press. p. 168.

- ^ Bookchin, Murray (1998). The Spanish Anarchists: The Heroic Years, 1868-1936 (illustrated revised ed.). Oakland: AK Press. p. 25. ISBN 9781873176047.

- ^ Maximoff, G. P. (1953). Political Philosophy of Bakunin. New York: Free Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780029012000.

Bibliography

[edit]- Backer, Thomas B. (1978). The Mutualists: The Heirs of Proudhon in the First International, 1865–1878. University of Cincinnati.

- Carson, Kevin (2018). "Anarchism and Markets". In Jun, Nathan (ed.). Brill's Companion to Anarchism and Philosophy. Leiden: Brill. pp. 81–119. doi:10.1163/9789004356894_005. ISBN 978-90-04-35689-4.

- Castleton, Edward (2017). "Association, Mutualism, and Corporate Form in the Published and Unpublished Writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon". History of Economic Ideas. 25 (1): 143–172. doi:10.19272/201706101006. ISSN 1724-2169. JSTOR 44806325.

- Douglas, Dorothy W. (1929). "P. J. Proudhon: A Prophet of 1848. Part I: Life and Works". American Journal of Sociology. 34 (5): 781–803. doi:10.1086/214822. ISSN 0002-9602. S2CID 264622055.

- Lloveras, Javier; Warnaby, Gary; Quinn, Lee (2020). "Mutualism as market practice: An examination of market performativity in the context of anarchism and its implications for post-capitalist politics" (PDF). Marketing Theory. 20 (3): 229–249. doi:10.1177/1470593119885172. ISSN 1470-5931. S2CID 210535234.

- Marshall, Peter H. (1993). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Fontana Press. ISBN 978-0-00-686245-1. OCLC 1042028128.

- Martin, James J. (1970) [1953]. Men Against the State: The Expositors of Individualist Anarchism in America, 1827-1908. Colorado Springs: Ralph Myles Publisher. ISBN 9780879260064. OCLC 8827896.

- North, Peter (2007). "Utopians, Anarchists, and Populists: The Politics of Money in the Nineteenth Century". Money and Liberation: The Micropolitics of Alternative Currency Movements. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 41–61. ISBN 978-0-8166-4962-4. JSTOR 10.5749/j.ctttt87r. LCCN 2006038757.

- Shantz, Jeff (2009). "Mutualism". In Ness, Immanuel (ed.). The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest. pp. 1–3. doi:10.1002/9781405198073.wbierp1058. ISBN 9781405198073.

- Wilbur, Shawn P. (2019). "Mutualism". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 213–224. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_11. ISBN 978-3319756196. S2CID 242074567.

- van der Linden, Marcel (2018). "Mutualism". In Hofmeester, Karin; van der Linden, Marcel (eds.). Handbook The Global History of Work. De Gruyter. pp. 491–504. ISBN 978-3-11-042835-3.

- Vest, J. Martin (2020). "Barbarians in the Agora: American Market Anarchism, 1945–2011". In Chartier, Gary; Van Schoelandt, Chad (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Anarchy and Anarchist Thought. New York: Routledge. pp. 112–125. doi:10.4324/9781315185255-8. ISBN 9781315185255. S2CID 228898569.

Further reading

[edit]- Benello, C. George (1992). Krimerman, Len; Lidenfeld, Frank; Korty, Carol; Benello, Julian (eds.). From the Ground Up: Essays on Grassroots and Workplace Democracy. Boston: South End Press. ISBN 0-89608-390-X. LCCN 91-28535. OCLC 24376378.

- Borsodi, Ralph (2019) [1929]. This Ugly Civilization. Baltimore: Underworld Amusements. ISBN 9781943687220. OCLC 1244870407.

- Carson, Kevin (2007). Studies in Mutualist Political Economy. Self-published. ISBN 978-1419658693. OCLC 172923433.

- Carson, Kevin (2008). Organization Theory: A Libertarian Perspective. BookSurge. ISBN 978-1439221990. OCLC 311323130.

- Carson, Kevin (2010). The Homebrew Industrial Revolution: A Low Overhead Manifesto. BookSurge. ISBN 9781439266991. OCLC 697667745.

- Carson, Kevin (2016). The Desktop Regulatory State: The Countervailing Power of Individuals and Networks. Center for a Stateless Society. ISBN 978-1523275595.

- De Cleyre, Voltairine (2005). "Anarchism". In Presley, Sharon; Sartwell, Crispin (eds.). Exquisite Rebel: The Essays of Voltairine de Cleyre. SUNY Press. pp. 67–82. ISBN 978-0-7914-6093-1. LCCN 2004059138.

- De Cleyre, Voltairine (2005). "Anarchism and American traditions". In Presley, Sharon; Sartwell, Crispin (eds.). Exquisite Rebel: The Essays of Voltairine de Cleyre. SUNY Press. pp. 89–102. ISBN 978-0-7914-6093-1. LCCN 2004059138.

- Gesell, Silvio (1958) [1916]. The Natural Economic Order. Translated by Pye, Philip. London: Peter Owen Publishers. OCLC 920780.

- Goodman, Paul (1977). Stoehr, Taylor (ed.). Drawing the Line: The Political Essays of Paul Goodman. New York: Free Life Editions. ISBN 0-914156-17-9. LCCN 77-71943. OCLC 3417667.

- Greene, William Batchelder (1919) [1850]. Mutual Banking. Denver: Reform League. OCLC 645147153.

- Greene, William Batchelder (1875). "Communism vs. Mutualism". Socialistic, Communistic, Mutualistic and Financial Fragments. Boston: Lee & Shepard. OCLC 2567184.

- Kuehn, Herman (1901). The Problem of Worry: The Principles of Scientific Mutualism Applied to Modern Commerce. Chicago: N. B. Irving. OCLC 33202070.

- Lum, Dyer (1886). "Communal Anarchy". The Alarm. Vol. 2, no. 15. p. 2 – via The Libertarian Labyrinth.

- Lum, Dyer (1890). The Economics of Anarchy: A Study of the Industrial Type. Chicago: George A. Schilling. OCLC 7982163.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1876) [1840]. . Translated by Tucker, Benjamin – via Wikisource.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1888) [1847]. System of Economical Contradictions: or, The Philosophy of Poverty. Translated by Tucker, Benjamin.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1849). – via Wikisource.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1989) [1851]. The General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century. Translated by Robinson, John Beverley. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 9781853050671. OCLC 220879063.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (2012) [1853]. The Philosophy of Progress. Translated by Wilbur, Shawn P. Libertarian Labyrinth.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1979) [1863]. The Principle of Federation. Translated by Vernon, Richard. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4875-7422-2. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctvcj2hr8.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1865). De la Capacité politique des classes ouvrières [On the political capacity of the working classes] (in French). Paris: E. Dentu.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1927). Cohen, Henry (ed.). The Solution of the Social Problem. New York: Vanguard Press. ISBN 0877000441. OCLC 2197518.

- Seymour, Henry (1894). "The Two Anarchisms". London: Proudhon Press.

- Swartz, Clarence Lee (1945) [1927]. What Is Mutualism?. New York: Modern Publishers. OCLC 19347096.

- Tucker, Benjamin (1897) [1893]. "State Socialism and Anarchism: How Far They Agree, And Wherein They Differ". Instead Of A Book, By A Man Too Busy To Write One (2nd ed.). pp. 1–18.

- Warren, Josiah (1852) [1846]. Equitable Commerce: A New Development of Principles for the Harmonious Adjustment and Regulation of the Pecuniary, Intellectual and Moral Intercourse of Mankind, Proposed as Elements of New Society. New York: Fowler & Wells Company. OCLC 489195268. OL 23157421M.

- Westrup, Alfred B. (1895). The New Philosophy of Money: A Practical Treatise on the Nature and Office of Money and the Correct Method of its Supply. Minneapolis: F. E. Leonard. OCLC 4739315.

External links

[edit]- Carson, Kevin (2006). Studies in Mutualist Political Economy. BookSurge Publishing.

- Gambone, Larry (1996). Proudhon and Anarchism: Proudhon's Libertarian Thought and the Anarchist Movement. Red Lion Press.

- Greene, William Batchelder (1850). Mutual Banking: Showing the Radical Deficiency of the Present Circulating Medium and the Advantages of a Free Currency.

- Kropotkin, Peter (1902). Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution.

- Lloyd, J. William (1927). Anarchist-Mutualism. Individualist anarchist criticism.

- Long, Roderick T., ed. (Winter 2006). Journal of Libertarian Studies 20 (1). This issue is devoted to Kevin Carson's Studies in Mutualist Political Economy and includes critiques and Carson's rejoinders.

- Reisman, George (18 June 2006). Mutualism: A Philosophy for Thieves. Mises Institute. Austrian School and Objectivist criticism.

- Swartz, Clarence Lee. (1927). What Is Mutualism?.

- Warren, Josiah (1829). Plan of the Cincinnati Labor for Labor Store. Mechanics Free Press.

- Weisbord, Albert (1937). "Mutualism". The Conquest of Power.

- Carson, Kevin, et al. "A Mutualist FAQ". Mutualist: Free-Market Anti-Capitalism.

- Mutualism (economic theory)

- Anarchist economic schools

- Anarchist schools of thought

- Anti-capitalism

- Economic theories

- Free-market anarchism

- Individualist anarchism

- Left-libertarianism

- Left-wing politics

- Libertarian socialism

- Libertarianism by form

- Market socialism

- Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

- Schools of economic thought

- Social anarchism

- Types of socialism