Formaldehyde

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Formaldehyde[1] | |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Methanal[1] | |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 1209228 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.002 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| E number | E240 (preservatives) | ||

| 445 | |||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Formaldehyde | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 2209 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties[7] | |||

| CH2O | |||

| Molar mass | 30.026 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless gas | ||

| Density | 0.8153 g/cm3 (−20 °C)[2] (liquid) | ||

| Melting point | −92 °C (−134 °F; 181 K) | ||

| Boiling point | −19 °C (−2 °F; 254 K)[2] | ||

| 400 g/L | |||

| log P | 0.350 | ||

| Vapor pressure | > 1 atm[3] | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 13.27 (hydrate)[4][5] | ||

| −18.6·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| 2.330 D[6] | |||

| Structure | |||

| C2v | |||

| Trigonal planar | |||

| Thermochemistry[8] | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

35.387 J·mol−1·K−1 | ||

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

218.760 J·mol−1·K−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−108.700 kJ·mol−1 | ||

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵)

|

−102.667 kJ·mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

571 kJ·mol−1 | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

| QP53AX19 (WHO) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling: | |||

[9] [9]

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H301+H311+H331, H314, H317, H335, H341, H350, H370[9] | |||

| P201, P280, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340+P310, P305+P351+P338, P308+P310[9] | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 64 °C (147 °F; 337 K) | ||

| 430 °C (806 °F; 703 K) | |||

| Explosive limits | 7–73% | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

100 mg/kg (oral, rat)[12] | ||

LC50 (median concentration)

|

333 ppm (mouse, 2 h) 815 ppm (rat, 30 min)[13] | ||

LCLo (lowest published)

|

333 ppm (cat, 2 h)[13] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 0.75 ppm ST 2 ppm (as formaldehyde and formalin)[10][11] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

Ca TWA 0.016 ppm C 0.1 ppm [15-minute][10] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

Ca [20 ppm][10] | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | MSDS(Archived) | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related aldehydes

|

|||

Related compounds

|

|||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Formaldehyde (/fɔːrˈmældɪhaɪd/ ⓘ for-MAL-di-hide, US also /fər-/ ⓘ fər-) (systematic name methanal) is an organic compound with the chemical formula CH2O and structure H−CHO, more precisely H2C=O. The compound is a pungent, colourless gas that polymerises spontaneously into paraformaldehyde. It is stored as aqueous solutions (formalin), which consists mainly of the hydrate CH2(OH)2. It is the simplest of the aldehydes (R−CHO). As a precursor to many other materials and chemical compounds, in 2006 the global production of formaldehyde was estimated at 12 million tons per year.[14] It is mainly used in the production of industrial resins, e.g., for particle board and coatings. Small amounts also occur naturally.

Formaldehyde is classified as a carcinogen[note 1] and can cause respiratory and skin irritation upon exposure.[15]

Forms

[edit]Formaldehyde is more complicated than many simple carbon compounds in that it adopts several diverse forms. These compounds can often be used interchangeably and can be interconverted.[citation needed]

- Molecular formaldehyde. A colorless gas with a characteristic pungent, irritating odor. It is stable at about 150 °C, but polymerizes when condensed to a liquid.

- 1,3,5-Trioxane, with the formula (CH2O)3. It is a white solid that dissolves without degradation in organic solvents. It is a trimer of molecular formaldehyde.

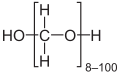

- Paraformaldehyde, with the formula HO(CH2O)nH. It is a white solid that is insoluble in most solvents.

- Methanediol, with the formula CH2(OH)2. This compound also exists in equilibrium with various oligomers (short polymers), depending on the concentration and temperature. A saturated water solution, of about 40% formaldehyde by volume or 37% by mass, is called "100% formalin".

A small amount of stabilizer, such as methanol, is usually added to suppress oxidation and polymerization. A typical commercial-grade formalin may contain 10–12% methanol in addition to various metallic impurities.

"Formaldehyde" was first used as a generic trademark in 1893 following a previous trade name, "formalin".[16]

- Main forms of formaldehyde

-

Monomeric formaldehyde (subject of this article)

-

Trioxane is a stable cyclic trimer of formaldehyde.

-

Paraformaldehyde is a common form of formaldehyde for industrial applications.

-

Methanediol, the predominant species in dilute aqueous solutions of formaldehyde

Structure and bonding

[edit]Molecular formaldehyde contains a central carbon atom with a double bond to the oxygen atom and a single bond to each hydrogen atom. This structure is summarised by the condensed formula H2C=O.[17] The molecule is planar, Y-shaped and its molecular symmetry belongs to the C2v point group.[18] The precise molecular geometry of gaseous formaldehyde has been determined by gas electron diffraction[17][19] and microwave spectroscopy.[20][21] The bond lengths are 1.21 Å for the carbon–oxygen bond[17][19][20][21][22] and around 1.11 Å for the carbon–hydrogen bond,[17][19][20][21] while the H–C–H bond angle is 117°,[20][21] close to the 120° angle found in an ideal trigonal planar molecule.[17] Some excited electronic states of formaldehyde are pyramidal rather than planar as in the ground state.[22]

Occurrence

[edit]Processes in the upper atmosphere contribute more than 80% of the total formaldehyde in the environment.[23] Formaldehyde is an intermediate in the oxidation (or combustion) of methane, as well as of other carbon compounds, e.g. in forest fires, automobile exhaust, and tobacco smoke. When produced in the atmosphere by the action of sunlight and oxygen on atmospheric methane and other hydrocarbons, it becomes part of smog. Formaldehyde has also been detected in outer space.

Formaldehyde and its adducts are ubiquitous in nature. Food may contain formaldehyde at levels 1–100 mg/kg.[24] Formaldehyde, formed in the metabolism of the amino acids serine and threonine, is found in the bloodstream of humans and other primates at concentrations of approximately 50 micromolar.[25] Experiments in which animals are exposed to an atmosphere containing isotopically labeled formaldehyde have demonstrated that even in deliberately exposed animals, the majority of formaldehyde-DNA adducts found in non-respiratory tissues are derived from endogenously produced formaldehyde.[26]

Formaldehyde does not accumulate in the environment, because it is broken down within a few hours by sunlight or by bacteria present in soil or water. Humans metabolize formaldehyde quickly, converting it to formic acid, so it does not accumulate.[27][28] It nonetheless presents significant health concerns, as a contaminant.

Interstellar formaldehyde

[edit]Formaldehyde appears to be a useful probe in astrochemistry due to prominence of the 110←111 and 211←212 K-doublet transitions. It was the first polyatomic organic molecule detected in the interstellar medium.[29] Since its initial detection in 1969, it has been observed in many regions of the galaxy. Because of the widespread interest in interstellar formaldehyde, it has been extensively studied, yielding new extragalactic sources.[30] A proposed mechanism for the formation is the hydrogenation of CO ice:[31]

- H + CO → HCO

- HCO + H → CH2O

HCN, HNC, H2CO, and dust have also been observed inside the comae of comets C/2012 F6 (Lemmon) and C/2012 S1 (ISON).[32][33]

Synthesis and industrial production

[edit]Laboratory synthesis

[edit]Formaldehyde was discovered in 1859 by the Russian chemist Aleksandr Butlerov (1828–1886) when he attempted to synthesize methanediol ("methylene glycol") from iodomethane and silver oxalate.[34] In his paper, Butlerov referred to formaldehyde as "dioxymethylen" (methylene dioxide) because his empirical formula for it was incorrect, as atomic weights were not precisely determined until the Karlsruhe Congress.

The compound was identified as an aldehyde by August Wilhelm von Hofmann, who first announced its production by passing methanol vapor in air over hot platinum wire.[35][36] With modifications, Hoffmann's method remains the basis of the present day industrial route.

Solution routes to formaldehyde also entail oxidation of methanol or iodomethane.[37]

Industry

[edit]Formaldehyde is produced industrially by the catalytic oxidation of methanol. The most common catalysts are silver metal, iron(III) oxide,[38] iron molybdenum oxides (e.g. iron(III) molybdate) with a molybdenum-enriched surface,[39] or vanadium oxides. In the commonly used formox process, methanol and oxygen react at c. 250–400 °C in presence of iron oxide in combination with molybdenum and/or vanadium to produce formaldehyde according to the chemical equation:[40]

- 2 CH3OH + O2 → 2 CH2O + 2 H2O

The silver-based catalyst usually operates at a higher temperature, about 650 °C. Two chemical reactions on it simultaneously produce formaldehyde: that shown above and the dehydrogenation reaction:

- CH3OH → CH2O + H2

In principle, formaldehyde could be generated by oxidation of methane, but this route is not industrially viable because the methanol is more easily oxidized than methane.[40]

Biochemistry

[edit]Formaldehyde is produced via several enzyme-catalyzed routes.[41] Living beings, including humans, produce formaldehyde as part of their metabolism. Formaldehyde is key to several bodily functions (e.g. epigenetics[25]), but its amount must also be tightly controlled to avoid self-poisoning.[42]

- Serine hydroxymethyltransferase can decompose serine into formaldehyde and glycine, according to this reaction: HOCH2CH(NH2)CO2H → CH2O + H2C(NH2)CO2H.

- Methylotrophic microbes convert methanol into formaldehyde and energy via methanol dehydrogenase: CH3OH → CH2O + 2e− + 2H+

- Other routes to formaldehyde include oxidative demethylations, semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidases, dimethylglycine dehydrogenases, lipid peroxidases, P450 oxidases, and N-methyl group demethylases.[41]

Formaldehyde is catabolized by alcohol dehydrogenase ADH5 and aldehyde dehydrogenase ALDH2.[43]

Organic chemistry

[edit]Formaldehyde is a building block in the synthesis of many other compounds of specialised and industrial significance. It exhibits most of the chemical properties of other aldehydes but is more reactive.[citation needed]

Polymerization and hydration

[edit]Monomeric CH2O is a gas and is rarely encountered in the laboratory. Aqueous formaldehyde, unlike some other small aldehydes (which need specific conditions to oligomerize through aldol condensation) oligomerizes spontaneously at a common state. The trimer 1,3,5-trioxane, (CH2O)3, is a typical oligomer. Many cyclic oligomers of other sizes have been isolated. Similarly, formaldehyde hydrates to give the geminal diol methanediol, which condenses further to form hydroxy-terminated oligomers HO(CH2O)nH. The polymer is called paraformaldehyde. The higher concentration of formaldehyde—the more equilibrium shifts towards polymerization. Diluting with water or increasing the solution temperature, as well as adding alcohols (such as methanol or ethanol) lowers that tendency.

Gaseous formaldehyde polymerizes at active sites on vessel walls, but the mechanism of the reaction is unknown.[44] Small amounts of hydrogen chloride, boron trifluoride, or stannic chloride present in gaseous formaldehyde provide the catalytic effect and make the polymerization rapid.[45]

Cross-linking reactions

[edit]Formaldehyde forms cross-links by first combining with a protein to form methylol, which loses a water molecule to form a Schiff base.[46] The Schiff base can then react with DNA or protein to create a cross-linked product.[46] This reaction is the basis for the most common process of chemical fixation.

Oxidation and reduction

[edit]Formaldehyde is readily oxidized by atmospheric oxygen into formic acid. For this reason, commercial formaldehyde is typically contaminated with formic acid. Formaldehyde can be hydrogenated into methanol.

In the Cannizzaro reaction, formaldehyde and base react to produce formic acid and methanol, a disproportionation reaction.

Hydroxymethylation and chloromethylation

[edit]Formaldehyde reacts with many compounds, resulting in hydroxymethylation:

- X-H + CH2O → X-CH2OH (X = R2N, RC(O)NR', SH).

The resulting hydroxymethyl derivatives typically react further. Thus, amines give hexahydro-1,3,5-triazines:

- 3 RNH2 + 3 CH2O → (RNCH2)3 + 3 H2O

Similarly, when combined with hydrogen sulfide, it forms trithiane:[47]

- 3 CH2O + 3 H2S → (CH2S)3 + 3 H2O

In the presence of acids, it participates in electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions with aromatic compounds resulting in hydroxymethylated derivatives:

- ArH + CH2O → ArCH2OH

When conducted in the presence of hydrogen chloride, the product is the chloromethyl compound, as described in the Blanc chloromethylation. If the arene is electron-rich, as in phenols, elaborate condensations ensue. With 4-substituted phenols one obtains calixarenes.[48] Phenol results in polymers.

Other reactions

[edit]Many amino acids react with formaldehyde.[41] Cysteine converts to thioproline.

Uses

[edit]Industrial applications

[edit]Formaldehyde is a common precursor to more complex compounds and materials. In approximate order of decreasing consumption, products generated from formaldehyde include urea formaldehyde resin, melamine resin, phenol formaldehyde resin, polyoxymethylene plastics, 1,4-butanediol, and methylene diphenyl diisocyanate.[40] The textile industry uses formaldehyde-based resins as finishers to make fabrics crease-resistant.[49]

When condensed with phenol, urea, or melamine, formaldehyde produces, respectively, hard thermoset phenol formaldehyde resin, urea formaldehyde resin, and melamine resin. These polymers are permanent adhesives used in plywood and carpeting. They are also foamed to make insulation, or cast into moulded products. Production of formaldehyde resins accounts for more than half of formaldehyde consumption.

Formaldehyde is also a precursor to polyfunctional alcohols such as pentaerythritol, which is used to make paints and explosives. Other formaldehyde derivatives include methylene diphenyl diisocyanate, an important component in polyurethane paints and foams, and hexamine, which is used in phenol-formaldehyde resins as well as the explosive RDX.

Condensation with acetaldehyde affords pentaerythritol, a chemical necessary in synthesizing PETN, a high explosive:[50]

Niche uses

[edit]Disinfectant and biocide

[edit]An aqueous solution of formaldehyde can be useful as a disinfectant as it kills most bacteria and fungi (including their spores). It is used as an additive in vaccine manufacturing to inactivate toxins and pathogens.[51] Formaldehyde releasers are used as biocides in personal care products such as cosmetics. Although present at levels not normally considered harmful, they are known to cause allergic contact dermatitis in certain sensitised individuals.[52]

Aquarists use formaldehyde as a treatment for the parasites Ichthyophthirius multifiliis and Cryptocaryon irritans.[53] Formaldehyde is one of the main disinfectants recommended for destroying anthrax.[54]

Formaldehyde is also approved for use in the manufacture of animal feeds in the US. It is an antimicrobial agent used to maintain complete animal feeds or feed ingredients Salmonella negative for up to 21 days.[55]

Tissue fixative and embalming agent

[edit]

Formaldehyde preserves or fixes tissue or cells. The process involves cross-linking of primary amino groups. The European Union has banned the use of formaldehyde as a biocide (including embalming) under the Biocidal Products Directive (98/8/EC) due to its carcinogenic properties.[56][57] Countries with a strong tradition of embalming corpses, such as Ireland and other colder-weather countries, have raised concerns. Despite reports to the contrary,[58] no decision on the inclusion of formaldehyde on Annex I of the Biocidal Products Directive for product-type 22 (embalming and taxidermist fluids) had been made as of September 2009[update].[59]

Formaldehyde-based crosslinking is exploited in ChIP-on-chip or ChIP-sequencing genomics experiments, where DNA-binding proteins are cross-linked to their cognate binding sites on the chromosome and analyzed to determine what genes are regulated by the proteins. Formaldehyde is also used as a denaturing agent in RNA gel electrophoresis, preventing RNA from forming secondary structures. A solution of 4% formaldehyde fixes pathology tissue specimens at about one mm per hour at room temperature.

Drug testing

[edit]Formaldehyde and 18 M (concentrated) sulfuric acid makes Marquis reagent—which can identify alkaloids and other compounds.

Photography

[edit]In photography, formaldehyde is used in low concentrations for the process C-41 (color negative film) stabilizer in the final wash step,[60] as well as in the process E-6 pre-bleach step, to make it unnecessary in the final wash. Due to improvements in dye coupler chemistry, more modern (2006 or later) E-6 and C-41 films do not need formaldehyde, as their dyes are already stable.

Safety

[edit]In view of its widespread use, toxicity, and volatility, formaldehyde poses a significant danger to human health.[61][62] In 2011, the US National Toxicology Program described formaldehyde as "known to be a human carcinogen".[63][64][65]

Chronic inhalation

[edit]This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: A little too scattered among different types of risks. Needs some reorganization. (November 2023) |

Concerns are associated with chronic (long-term) exposure by inhalation as may happen from thermal or chemical decomposition of formaldehyde-based resins and the production of formaldehyde resulting from the combustion of a variety of organic compounds (for example, exhaust gases). As formaldehyde resins are used in many construction materials, it is one of the more common indoor air pollutants.[66][67] At concentrations above 0.1 ppm in air, formaldehyde can irritate the eyes and mucous membranes.[68] Formaldehyde inhaled at this concentration may cause headaches, a burning sensation in the throat, and difficulty breathing, and can trigger or aggravate asthma symptoms.[69][70]

The CDC considers formaldehyde as a systemic poison. Formaldehyde poisoning can cause permanent changes in the nervous system's functions.[71]

A 1988 Canadian study of houses with urea-formaldehyde foam insulation found that formaldehyde levels as low as 0.046 ppm were positively correlated with eye and nasal irritation.[72] A 2009 review of studies has shown a strong association between exposure to formaldehyde and the development of childhood asthma.[73]

A theory was proposed for the carcinogenesis of formaldehyde in 1978.[74] In 1987 the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) classified it as a probable human carcinogen, and after more studies the WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in 1995 also classified it as a probable human carcinogen. Further information and evaluation of all known data led the IARC to reclassify formaldehyde as a known human carcinogen[75] associated with nasal sinus cancer and nasopharyngeal cancer.[76] Studies in 2009 and 2010 have also shown a positive correlation between exposure to formaldehyde and the development of leukemia, particularly myeloid leukemia.[77][78] Nasopharyngeal and sinonasal cancers are relatively rare, with a combined annual incidence in the United States of < 4,000 cases.[79][80] About 30,000 cases of myeloid leukemia occur in the United States each year.[81][82] Some evidence suggests that workplace exposure to formaldehyde contributes to sinonasal cancers.[83] Professionals exposed to formaldehyde in their occupation, such as funeral industry workers and embalmers, showed an increased risk of leukemia and brain cancer compared with the general population.[84] Other factors are important in determining individual risk for the development of leukemia or nasopharyngeal cancer.[83][85][86] In yeast, formaldehyde is found to perturb pathways for DNA repair and cell cycle.[87]

In the residential environment, formaldehyde exposure comes from a number of routes; formaldehyde can be emitted by treated wood products, such as plywood or particle board, but it is produced by paints, varnishes, floor finishes, and cigarette smoking as well.[88] In July 2016, the U.S. EPA released a prepublication version of its final rule on Formaldehyde Emission Standards for Composite Wood Products.[89] These new rules impact manufacturers, importers, distributors, and retailers of products containing composite wood, including fiberboard, particleboard, and various laminated products, who must comply with more stringent record-keeping and labeling requirements.[90]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

The U.S. EPA allows no more than 0.016 ppm formaldehyde in the air in new buildings constructed for that agency.[91][failed verification] A U.S. EPA study found a new home measured 0.076 ppm when brand new and 0.045 ppm after 30 days.[92] The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has also announced limits on the formaldehyde levels in trailers purchased by that agency.[93] The EPA recommends the use of "exterior-grade" pressed-wood products with phenol instead of urea resin to limit formaldehyde exposure, since pressed-wood products containing formaldehyde resins are often a significant source of formaldehyde in homes.[76]

The eyes are most sensitive to formaldehyde exposure: The lowest level at which many people can begin to smell formaldehyde ranges between 0.05 and 1 ppm. The maximum concentration value at the workplace is 0.3 ppm.[94][need quotation to verify] In controlled chamber studies, individuals begin to sense eye irritation at about 0.5 ppm; 5 to 20 percent report eye irritation at 0.5 to 1 ppm; and greater certainty for sensory irritation occurred at 1 ppm and above. While some agencies have used a level as low as 0.1 ppm as a threshold for irritation, the expert panel found that a level of 0.3 ppm would protect against nearly all irritation. In fact, the expert panel found that a level of 1.0 ppm would avoid eye irritation—the most sensitive endpoint—in 75–95% of all people exposed.[95]

Formaldehyde levels in building environments are affected by a number of factors. These include the potency of formaldehyde-emitting products present, the ratio of the surface area of emitting materials to volume of space, environmental factors, product age, interactions with other materials, and ventilation conditions. Formaldehyde emits from a variety of construction materials, furnishings, and consumer products. The three products that emit the highest concentrations are medium density fiberboard, hardwood plywood, and particle board. Environmental factors such as temperature and relative humidity can elevate levels because formaldehyde has a high vapor pressure. Formaldehyde levels from building materials are the highest when a building first opens because materials would have less time to off-gas. Formaldehyde levels decrease over time as the sources suppress.

In operating rooms, formaldehyde is produced as a byproduct of electrosurgery and is present in surgical smoke, exposing surgeons and healthcare workers to potentially unsafe concentrations.[96]

Formaldehyde levels in air can be sampled and tested in several ways, including impinger, treated sorbent, and passive monitors.[97] The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has measurement methods numbered 2016, 2541, 3500, and 3800.[98]

In June 2011, the twelfth edition of the National Toxicology Program (NTP) Report on Carcinogens (RoC) changed the listing status of formaldehyde from "reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen" to "known to be a human carcinogen."[63][64][65] Concurrently, a National Academy of Sciences (NAS) committee was convened and issued an independent review of the draft U.S. EPA IRIS assessment of formaldehyde, providing a comprehensive health effects assessment and quantitative estimates of human risks of adverse effects.[99]

Acute irritation and allergic reaction

[edit]

For most people, irritation from formaldehyde is temporary and reversible, although formaldehyde can cause allergies and is part of the standard patch test series. In 2005–06, it was the seventh-most-prevalent allergen in patch tests (9.0%).[100] People with formaldehyde allergy are advised to avoid formaldehyde releasers as well (e.g., Quaternium-15, imidazolidinyl urea, and diazolidinyl urea).[101] People who suffer allergic reactions to formaldehyde tend to display lesions on the skin in the areas that have had direct contact with the substance, such as the neck or thighs (often due to formaldehyde released from permanent press finished clothing) or dermatitis on the face (typically from cosmetics).[52] Formaldehyde has been banned in cosmetics in both Sweden[102] and Japan.[103]

Other routes

[edit]Formaldehyde occurs naturally, and is "an essential intermediate in cellular metabolism in mammals and humans."[40] According to the American Chemistry Council, "Formaldehyde is found in every living system—from plants to animals to humans. It metabolizes quickly in the body, breaks down rapidly, is not persistent and does not accumulate in the body."[104]

The twelfth edition of NTP Report on Carcinogens notes that "food and water contain measureable concentrations of formaldehyde, but the significance of ingestion as a source of formaldehyde exposure for the general population is questionable." Food formaldehyde generally occurs in a bound form and formaldehyde is unstable in an aqueous solution.[65]

In humans, ingestion of as little as 30 millilitres (1.0 US fl oz) of 37% formaldehyde solution can cause death. Other symptoms associated with ingesting such a solution include gastrointestinal damage (vomiting, abdominal pain), and systematic damage (dizziness).[71] Testing for formaldehyde is by blood and/or urine by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Other methods include infrared detection, gas detector tubes, etc., of which high-performance liquid chromatography is the most sensitive.[105]

Regulation

[edit]Several web articles[like whom?] claim that formaldehyde has been banned from manufacture or import into the European Union (EU) under REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorization, and restriction of Chemical substances) legislation. That is a misconception, as formaldehyde is not listed in the Annex I of Regulation (EC) No 689/2008 (export and import of dangerous chemicals regulation), nor on a priority list for risk assessment. However, formaldehyde is banned from use in certain applications (preservatives for liquid-cooling and processing systems, slimicides, metalworking-fluid preservatives, and antifouling products) under the Biocidal Products Directive.[106][107] In the EU, the maximum allowed concentration of formaldehyde in finished products is 0.2%, and any product that exceeds 0.05% has to include a warning that the product contains formaldehyde.[52]

In the United States, Congress passed a bill July 7, 2010, regarding the use of formaldehyde in hardwood plywood, particle board, and medium density fiberboard. The bill limited the allowable amount of formaldehyde emissions from these wood products to 0.09 ppm, and required companies to meet this standard by January 2013.[108] The final U.S. EPA rule specified maximum emissions of "0.05 ppm formaldehyde for hardwood plywood, 0.09 ppm formaldehyde for particleboard, 0.11 ppm formaldehyde for medium-density fiberboard, and 0.13 ppm formaldehyde for thin medium-density fiberboard."[109]

Formaldehyde was declared a toxic substance by the 1999 Canadian Environmental Protection Act.[110]

The FDA is proposing a ban on hair relaxers with formaldehyde due to cancer concerns.[111]

Contaminant in food

[edit]Scandals have broken in both the 2005 Indonesia food scare and 2007 Vietnam food scare regarding the addition of formaldehyde to foods to extend shelf life. In 2011, after a four-year absence, Indonesian authorities found foods with formaldehyde being sold in markets in a number of regions across the country.[112] In August 2011, at least at two Carrefour supermarkets, the Central Jakarta Livestock and Fishery Sub-Department found cendol containing 10 parts per million of formaldehyde.[113] In 2014, the owner of two noodle factories in Bogor, Indonesia, was arrested for using formaldehyde in noodles. 50 kg of formaldehyde was confiscated.[114] Foods known to be contaminated included noodles, salted fish, and tofu. Chicken and beer were also rumored to be contaminated. In some places, such as China, manufacturers still use formaldehyde illegally as a preservative in foods, which exposes people to formaldehyde ingestion.[115] In the early 1900s, it was frequently added by US milk plants to milk bottles as a method of pasteurization due to the lack of knowledge and concern[116] regarding formaldehyde's toxicity.[117][118]

In 2011 in Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand, truckloads of rotten chicken were treated with formaldehyde for sale in which "a large network", including 11 slaughterhouses run by a criminal gang, were implicated.[119] In 2012, 1 billion rupiah (almost US$100,000) of fish imported from Pakistan to Batam, Indonesia, were found laced with formaldehyde.[120]

Formalin contamination of foods has been reported in Bangladesh, with stores and supermarkets selling fruits, fishes, and vegetables that have been treated with formalin to keep them fresh.[121] However, in 2015, a Formalin Control Bill was passed in the Parliament of Bangladesh with a provision of life-term imprisonment as the maximum punishment as well as a maximum fine of 2,000,000 BDT but not less than 500,000 BDT for importing, producing, or hoarding formalin without a license.[122]

Formaldehyde was one of the chemicals used in 19th century industrialised food production that was investigated by Dr. Harvey W. Wiley with his famous 'Poison Squad' as part of the US Department of Agriculture. This led to the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act, a landmark event in the early history of food regulation in the United States.[123]

See also

[edit]- 1,3-Dioxetane

- DMDM hydantoin

- Sawdust | Health impacts of sawdust

- Sulphobes

- Transition metal complexes of aldehydes and ketones

- Wood glue

- Wood preservation

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Front Matter". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 908. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ^ a b "SIDS Initial Assessment Report" (PDF). International Programme on Chemical Safety. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-28. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- ^ Spence, Robert; Wild, William (1935). "114. The vapour-pressure curve of formaldehyde, and some related data". Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 506–509. doi:10.1039/jr9350000506.

- ^ "PubChem Compound Database; CID=712". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 2019-04-12. Retrieved 2017-07-08.

- ^ "Acidity of aldehydes". Chemistry Stack Exchange. Archived from the original on 2018-09-01. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- ^ Nelson, R. D. Jr.; Lide, D. R.; Maryott, A. A. (1967). "Selected Values of electric dipole moments for molecules in the gas phase (NSRDS-NBS10)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-06-08. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- ^ Weast, Robert C., ed. (1981). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (62nd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. pp. C–301, E–61. ISBN 0-8493-0462-8.

- ^ CRC handbook of chemistry and physics: a ready-reference book of chemical and physical data. William M. Haynes, David R. Lide, Thomas J. Bruno (2016-2017, 97th ed.). Boca Raton, Florida. 2016. ISBN 978-1-4987-5428-6. OCLC 930681942. Archived from the original on 2022-05-04. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Record of Formaldehyde in the GESTIS Substance Database of the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, accessed on 13 March 2020.

- ^ a b c NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0293". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0294". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ "Substance Name: Formaldehyde [USP]". ChemlDplus. US National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2017-09-18.

- ^ a b "Formaldehyde". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Humans, IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to (2006). Summary of Data Reported and Evaluation. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Archived from the original on 2024-02-02. Retrieved 2023-03-06.

- ^ a b "Formaldehyde and Cancer Risk". 10 June 2011. Archived from the original on 2023-09-20. Retrieved 2023-09-21.

- ^ Formalin, Merriam-Webster, Inc., 15 January 2020, archived from the original on 18 April 2020, retrieved 18 February 2020

- ^ a b c d e Wells, A. F. (1984). Structural Inorganic Chemistry (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 915–917, 926. ISBN 978-0-19-965763-6.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 1291. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ a b c Chuichi, Kato; Shigehiro, Konaka; Takao, Iijima; Masao, Kimura (1969). "Electron Diffraction Studies of Formaldehyde, Acetaldehyde and Acetone". Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 42 (8): 2148–2158. doi:10.1246/bcsj.42.2148.

- ^ a b c d William M. Haynes, ed. (2012). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (93rd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 9–39. ISBN 978-1439880500.

- ^ a b c d Duncan, J. L. (1974). "The ground-state average and equilibrium structures of formaldehyde and ethylene". Mol. Phys. 28 (5): 1177–1191. Bibcode:1974MolPh..28.1177D. doi:10.1080/00268977400102501.

- ^ a b Smith, Michael B.; March, Jerry (2007). March's Advanced Organic Chemistry (6th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 24–25, 335. ISBN 978-0-471-72091-1.

- ^ Luecken, D. J.; Hutzell, W. T.; Strum, M. L.; Pouliot, G. A. (2012-02-01). "Regional sources of atmospheric formaldehyde and acetaldehyde, and implications for atmospheric modeling". Atmospheric Environment. 47: 477–490. Bibcode:2012AtmEn..47..477L. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.10.005. ISSN 1352-2310.

- ^ "Chapter 5.8 Formaldehyde" (PDF). Air Quality Guidelines (2nd ed.). Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe. 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-02-18. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ^ a b Pham, Vanha N.; Bruemmer, Kevin J.; Toh, Joel D. W.; Ge, Eva J.; Tenney, Logan; Ward, Carl C.; Dingler, Felix A.; Millington, Christopher L.; Garcia-Prieto, Carlos A.; Pulos-Holmes, Mia C.; Ingolia, Nicholas T.; Pontel, Lucas B.; Esteller, Manel; Patel, Ketan J.; Nomura, Daniel K.; Chang, Christopher J. (2023). "Formaldehyde regulates S -adenosylmethionine biosynthesis and one-carbon metabolism". Science. 382 (6670): eabp9201. Bibcode:2023Sci...382P9201P. doi:10.1126/science.abp9201. PMC 11500418. PMID 37917677. S2CID 264935787.

- ^ Swenberg, J. A.; Lu, K.; Moeller, B. C.; Gao, L.; Upton, P. B.; Nakamura, J.; Starr, T. B. (2011). "Endogenous versus Exogenous DNA Adducts: Their Role in Carcinogenesis, Epidemiology, and Risk Assessment". Toxicological Sciences. 120 (Suppl 1): S130–S145. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfq371. PMC 3043087. PMID 21163908.

- ^ "Formaldehyde Is Biodegradable, Quickly Broken Down in the Air By Sunlight or By Bacteria in Soil or Water" (Press release). Formaldehyde Panel of the American Chemistry Council. 2014-01-29. Archived from the original on 2019-03-28. Retrieved 2017-04-22.

- ^ . 2019-03-28 https://web.archive.org/web/20190328010414/https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp111.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-28. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Zuckerman, B.; Buhl, D.; Palmer, P.; Snyder, L. E. (1970). "Observation of interstellar formaldehyde". Astrophys. J. 160: 485–506. Bibcode:1970ApJ...160..485Z. doi:10.1086/150449.

- ^ Mangum, Jeffrey G.; Darling, Jeremy; Menten, Karl M.; Henkel, Christian (2008). "Formaldehyde Densitometry of Starburst Galaxies". Astrophys. J. 673 (2): 832–46. arXiv:0710.2115. Bibcode:2008ApJ...673..832M. doi:10.1086/524354. S2CID 14035123.

- ^ Woon, David E. (2002). "Modeling Gas-Grain Chemistry with Quantum Chemical Cluster Calculations. I. Heterogeneous Hydrogenation of CO and H2CO on Icy Grain Mantles". Astrophys. J. 569 (1): 541–48. Bibcode:2002ApJ...569..541W. doi:10.1086/339279.

- ^ Zubritsky, Elizabeth; Neal-Jones, Nancy (11 August 2014). "RELEASE 14-038 - NASA's 3-D Study of Comets Reveals Chemical Factory at Work". NASA. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ Cordiner, M.A.; et al. (11 August 2014). "Mapping the Release of Volatiles in the Inner Comae of Comets C/2012 F6 (Lemmon) and C/2012 S1 (ISON) Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array". The Astrophysical Journal. 792 (1): L2. arXiv:1408.2458. Bibcode:2014ApJ...792L...2C. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/792/1/L2. S2CID 26277035.

- ^ A. Butlerow (1859). "Ueber einige Derivate des Jodmethylens". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 111 (2): 242–252. doi:10.1002/JLAC.18591110219. ISSN 0075-4617. Wikidata Q55881565.

- ^ See: A. W. Hofmann (14 October 1867) "Zur Kenntnis des Methylaldehyds" ([Contributions] to our knowledge of methylaldehyde), Monatsbericht der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin (Monthly Report of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin), vol. 8, pages 665–669. Reprinted in:

- A.W. Hofmann, (1868) "Zur Kenntnis des Methylaldehyds", Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie (Annals of Chemistry and Pharmacy), vol. 145, no. 3, pages 357–361.

- A.W. Hofmann (1868) "Zur Kenntnis des Methylaldehyds", Journal für praktische Chemie (Journal for Practical Chemistry), vol. 103, no. 1, pages 246–250.

- Hofmann, A.W. (1869). "Beiträge zur Kenntnis des Methylaldehyds". Journal für Praktische Chemie. 107 (1): 414–424. doi:10.1002/prac.18691070161.

- A.W. Hofmann (1869) "Beiträge zur Kenntnis des Methylaldehyds," Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (Reports of the German Chemical Society), vol. 2, pages 152–159.

- ^ Read, J. (1935). Text-Book of Organic Chemistry. London: G Bell & Sons.

- ^ Hooker, Jacob M.; Schönberger, Matthias; Schieferstein, Hanno; Fowler, Joanna S. (2008). "A Simple, Rapid Method for the Preparation of [11C]Formaldehyde". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 47 (32): 5989–5992. doi:10.1002/anie.200800991. PMC 2522306. PMID 18604787.

- ^ Wang, Chien-Tsung; Ro, Shih-Hung (2005-05-10). "Nanocluster iron oxide-silica aerogel catalysts for methanol partial oxidation". Applied Catalysis A: General. 285 (1): 196–204. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2005.02.029. ISSN 0926-860X.

- ^ Dias, Ana Paula Soares; Montemor, Fátima; Portela, Manuel Farinha; Kiennemann, Alain (2015-02-01). "The role of the suprastoichiometric molybdenum during methanol to formaldehyde oxidation over Mo–Fe mixed oxides". Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical. 397: 93–98. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2014.10.022. ISSN 1381-1169.

- ^ a b c d Reuss, Günther; Disteldorf, Walter; Gamer, Armin Otto; Hilt, Albrecht (2000). "Formaldehyde". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_619. ISBN 3527306730.

- ^ a b c Kamps, Jos J. A. G.; Hopkinson, Richard J.; Schofield, Christopher J.; Claridge, Timothy D. W. (2019). "How formaldehyde reacts with amino acids". Communications Chemistry. 2. doi:10.1038/s42004-019-0224-2. S2CID 207913561.

- ^ Chen, J; Chen, W; Zhang, J; Zhao, H; Cui, J; Wu, J; Shi, A (27 September 2023). "Dual effects of endogenous formaldehyde on the organism and drugs for its removal". Journal of Applied Toxicology. 44 (6): 798–817. doi:10.1002/jat.4546. PMID 37766419. S2CID 263125399.

- ^ Nakamura, Jun; Holley, Darcy W.; Kawamoto, Toshihiro; Bultman, Scott J. (December 2020). "The failure of two major formaldehyde catabolism enzymes (ADH5 and ALDH2) leads to partial synthetic lethality in C57BL/6 mice". Genes and Environment. 42 (1): 21. Bibcode:2020GeneE..42...21N. doi:10.1186/s41021-020-00160-4. PMC 7268536. PMID 32514323.

- ^ Boyles, James G.; Toby, Sidney (June 1966). "The mechanism of the polymerization of gaseous formaldehyde". Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Letters. 4 (6): 411–415. Bibcode:1966JPoSL...4..411B. doi:10.1002/pol.1966.110040608. Archived from the original on 2023-04-20. Retrieved 2023-04-20.

- ^ Bevington, J. C.; Norrish, R. G. W. (1951-03-07). "The catalyzed polymerization of gaseous formaldehyde". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 205 (1083): 516–529. Bibcode:1951RSPSA.205..516B. doi:10.1098/rspa.1951.0046. ISSN 0080-4630. S2CID 95395629. Archived from the original on 2019-10-25. Retrieved 2023-04-20.

- ^ a b Hoffman EA, Frey BL, Smith LM, Auble DT (2015). "Formaldehyde crosslinking: a tool for the study of chromatin complexes". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 290 (44): 26404–26411. doi:10.1074/jbc.R115.651679. PMC 4646298. PMID 26354429.

- ^ Bost, R. W.; Constable, E. W. (1936). "sym-Trithiane". Organic Syntheses. 16: 81; Collected Volumes, vol. 2, p. 610.

- ^ Gutsche, C. D.; Iqbal, M. (1993). "p-tert-Butylcalix[4]arene". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 8, p. 75.

- ^ "Formaldehyde in Clothing and Textiles FactSheet". NICNAS. Australian National Industrial Chemicals Notification and Assessment Scheme. 2013-05-01. Archived from the original on 2019-03-19. Retrieved 2014-11-12.

- ^ Schurink, H. B. J. (1925). "Pentaerythritol". Organic Syntheses. 4: 53; Collected Volumes, vol. 1, p. 425.

- ^ "Ingredients of Vaccines - Fact Sheet". Center for Disease Control. Archived from the original on 2019-04-21. Retrieved 2018-08-04.

Formaldehyde is used to inactivate bacterial products for toxoid vaccines, (these are vaccines that use an inactive bacterial toxin to produce immunity.) It is also used to kill unwanted viruses and bacteria that might contaminate the vaccine during production. Most formaldehyde is removed from the vaccine before it is packaged.

- ^ a b c De Groot, Anton C; Flyvholm, Mari-Ann; Lensen, Gerda; Menné, Torkil; Coenraads, Pieter-Jan (2009). "Formaldehyde-releasers: relationship to formaldehyde contact allergy. Contact allergy to formaldehyde and inventory of formaldehyde-releasers". Contact Dermatitis. 61 (2): 63–85. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2009.01582.x. hdl:11370/c3ff7adf-9f21-4564-96e0-0b9c5d025b30. PMID 19706047. S2CID 23404196. Archived from the original on 2020-03-13. Retrieved 2019-07-08.

- ^ Francis-Floyd, Ruth (April 1996). "Use of Formalin to Control Fish Parasites". Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012.

- ^ "Disinfection, decontamination, fumigation, incineration", Anthrax in Humans and Animals. 4th edition, World Health Organization, 2008, archived from the original on 2022-07-06, retrieved 2023-11-20

- ^ "§573.460 Formaldehyde". U.S. Government Publishing Office. 2019-04-19. Archived from the original on 2017-05-05. Retrieved 2016-07-09.

- ^ Directive 98/8/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 February 1998 concerning the placing of biocidal products on the market Archived 19 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine. OJEU L123, 24.04.1998, pp. 1–63. (consolidated version to 2008-09-26 (PDF) Archived 2010-01-27 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Commission Regulation (EC) No 2032/2003 of 4 November 2003 on the second phase of the 10-year work programme referred to in Article 16(2) of Directive 98/8/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning the placing of biocidal products on the market, and amending Regulation (EC) No 1896/2000 Archived 12 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. OJEU L307, 24.11.2003, p. 1–96. (consolidated version to 2007-01-04 (PDF) Archived 2011-06-14 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Patel, Alkesh (2007-07-04). "Formaldehyde Ban set for 22 September 2007". WebWire. Archived from the original on 2018-12-12. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- ^ "European chemical Substances Information System (ESIS) entry for formaldehyde". Archived from the original on 2014-01-01. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- ^ "Process C-41 Using Kodak Flexicolor Chemicals - Publication Z-131". Kodak. Archived from the original on 2016-06-15. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- ^ "Formaldehyde", Formaldehyde, 2-Butoxyethanol and 1-tert-Butoxypropan-2-ol (PDF), IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans 88, Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2006, pp. 39–325, ISBN 978-92-832-1288-1, archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-03-04, retrieved 2009-09-01

- ^ "Formaldehyde (gas)", Report on Carcinogens, Eleventh Edition Archived 2019-08-06 at the Wayback Machine (PDF), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Toxicology Program, 2005

- ^ a b Harris, Gardiner (2011-06-10). "Government Says 2 Common Materials Pose Risk of Cancer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2019-03-28. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- ^ a b National Toxicology Program (2011-06-10). "12th Report on Carcinogens". National Toxicology Program. Archived from the original on 2011-06-08. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- ^ a b c National Toxicology Program (2011-06-10). "Report On Carcinogens - Twelfth Edition - 2011" (PDF). National Toxicology Program. Archived from the original on 2011-06-12. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- ^ "Formaldehyde in indoor air of new apartments in Greece" (PDF). Retrieved 2024-12-24. by George Mantanis, Eleni Vouli, Chariclea Gonitsioti and Georgios Ntalos; Presentation at the COST Action E49 Conference “Measurement and Control of VOC Emissions from Wood-Based Panels”, 28-30 Nov. 2007, WKI, Braunschweig, Germany

- ^ "Indoor Air Pollution in California" (PDF). Air Resources Board, California Environmental Protection Agency. July 2005. pp. 65–70. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-01. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- ^ "Formaldehyde". Occupational Safety and Health Administration. August 2008. Archived from the original on 2019-04-11. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- ^ "Formaldehyde Reference Exposure Levels". California Office Of Health Hazard Assessment. December 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-23. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- ^ "Formaldehyde and Indoor Air". Health Canada. 2012-03-29. Archived from the original on 2019-04-23. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- ^ a b "Formaldehyde | Medical Management Guidelines | Toxic Substance Portal | ATSDR". Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 2021-08-25. Retrieved 2021-08-25.

- ^ Broder, I; Corey, P; Brasher, P; Lipa, M; Cole, P (1991). "Formaldehyde exposure and health status in households". Environmental Health Perspectives. 95: 101–4. doi:10.1289/ehp.9195101. PMC 1568408. PMID 1821362.

- ^ McGwin, G; Lienert, J; Kennedy, JI (November 2009). "Formaldehyde Exposure and Asthma in Children: A Systematic Review". Environmental Health Perspectives. 118 (3): 313–7. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901143. PMC 2854756. PMID 20064771.

- ^ Lobachev, AN (1978). "РОЛЬ МИТОХОНДРИАЛЬНЫХ ПРОЦЕССОВ В РАЗВИТИИ И СТАРЕНИИ ОРГАНИЗМА. СТАРЕНИЕ И РАК" [Role of mitochondrial processes in the development and aging of organism. Aging and cancer] (PDF) (in Russian). VINITI. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-06. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- ^ IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (2006). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans - VOLUME 88 - Formaldehyde, 2-Butoxyethanol and 1-tert-Butoxypropan-2-ol (PDF). WHO Press. ISBN 92-832-1288-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-07-12. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- ^ a b "Formaldehyde and Cancer Risk". National Cancer Institute. 2011-06-10. Archived from the original on 2019-01-23.

- ^ Zhang, Luoping; Steinmaus, Craig; Eastmond, Eastmond; Xin, Xin; Smith, Smith (March–June 2009). "Formaldehyde exposure and leukemia: A new meta-analysis and potential mechanisms" (PDF). Mutation Research. 681 (2–3): 150–168. Bibcode:2009MRRMR.681..150Z. doi:10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.07.002. PMID 18674636. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2014.

- ^ Zhang, Luoping; Freeman, Laura E. Beane; Nakamura, Jun; Hecht, Stephen S.; Vandenberg, John J.; Smith, Martyn T.; Sonawane, Babasaheb R. (2010). "Formaldehyde and Leukemia: Epidemiology, Potential Mechanisms, and Implications for Risk Assessment". Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis. 51 (3): 181–191. Bibcode:2010EnvMM..51..181Z. doi:10.1002/em.20534. PMC 2839060. PMID 19790261.

- ^ "Key Statistics for Nasopharyngeal Cancer". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 2019-01-11. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ^ Turner JH, Reh DD (June 2012). "Incidence and survival in patients with sinonasal cancer: a historical analysis of population-based data". Head Neck. 34 (6): 877–85. doi:10.1002/hed.21830. PMID 22127982. S2CID 205857872.

- ^ "Key Statistics for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 2019-04-23. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ^ "What are the key statistics about acute myeloid leukemia?Key Statistics for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 2019-04-23. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ^ a b "Risk Factors for Nasopharyngeal Cancer". American Cancer Society. 24 September 2018. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ Butticè, Claudio (2015). "Solvents". In Colditz, Graham A. (ed.). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Cancer and Society (Second ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. pp. 1089–1091. doi:10.4135/9781483345758.n530. ISBN 9781483345734. Archived from the original on 2021-10-14. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ^ "Risk Factors for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)". American Cancer Society. 2018-08-21. Archived from the original on 2019-04-23.

- ^ "Risk Factors for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia". American Cancer Society. 2018-06-19. Archived from the original on 2018-12-12.

- ^ Ogbede, J. U., Giaever, G., & Nislow, C. (2021). A genome-wide portrait of pervasive drug contaminants. Scientific reports, 11(1), 12487. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91792-1 Archived 2021-12-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dales, R; Liu, L; Wheeler, AJ; Gilbert, NL (July 2008). "Quality of indoor residential air and health". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 179 (2): 147–52. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070359. PMC 2443227. PMID 18625986.

- ^ "Formaldehyde Emission Standards for Composite Wood Products". EPA. 8 July 2016. Archived from the original on 2018-12-24. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- ^ Passmore, Whitney; Sullivan, Michael J. (2016-08-04). "EPA Issues Final Rule on Formaldehyde Emission Standards for Composite Wood Products". The National Law Review. Womble Carlyle Sandridge & Rice, PLLC. Archived from the original on 2018-06-19. Retrieved 2016-08-24 – via Google News.

- ^ "Testing for Indoor Air Quality, Baseline IAQ, and Materials". Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on October 15, 2006.

- ^ M. Koontz, H. Rector, D. Cade, C. Wilkes, and L. Niang. 1996. Residential Indoor Air Formaldehyde Testing Program: Pilot Study. Report No. IE-2814, prepared by GEOMET Technologies, Inc. for the USEPA Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics under EPA Contract No. 68-D3-0013, Washington, DC

- ^ Evans, Ben (2008-04-11). "FEMA limits formaldehyde in trailers". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved 2008-09-04.

- ^ "Formaldehyde CAS 50-00-0" (PDF). United Nations Environment Programme. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-28. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- ^ Formaldehyde Epidemiology, Toxicology and Environmental Group, Inc (August 2002). "Formaldehyde and Facts About Health Effects" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carroll, Gregory T.; Kirschman, David L. (2023). "Catalytic Surgical Smoke Filtration Unit Reduces Formaldehyde Levels in a Simulated Operating Room Environment". ACS Chemical Health & Safety. 30 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1021/acs.chas.2c00071. ISSN 1871-5532. S2CID 255047115. Archived from the original on 2023-05-14. Retrieved 2023-05-17.

- ^ "When Sampling Formaldehyde, The Medium Matters". Galson Labs. Archived from the original on 2011-03-23.

- ^ "NIOSH Pocket Gide to Chemical Hazards: Formaldehyde". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, CDC. 2018-11-29. Archived from the original on 2019-03-28.

- ^ Addendum to the 12th Report on Carcinogens (PDF) Archived 2011-06-08 at the Wayback Machine National Toxicology Program, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 06-13-2011

- ^ Zug KA, Warshaw EM, Fowler JF, Maibach HI, Belsito DL, Pratt MD, Sasseville D, Storrs FJ, Taylor JS, Mathias CG, Deleo VA, Rietschel RL, Marks J (2009). "Patch-test results of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 2005-2006". Dermatitis. 20 (3): 149–60. doi:10.2310/6620.2009.08097. PMID 19470301. S2CID 24088485.

- ^ "Formaldehyde allergy". DermNet NZ. New Zealand Dermatological Society. 2002. Archived from the original on 2018-09-23. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- ^ "Formaldehyde And Formaldehyde-Releasing Preservatives". Safe Cosmetics. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ^ Hayashida, Mike. "The Regulation of Cosmetics in Japan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-04-14. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- ^ "Formaldehyde occurs naturally and is all around us" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2021-12-31.

- ^ Ngwa, Moise (2010-10-25). "formaldehyde testing" (PDF). Cedar Rapids Gazette. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-25. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- ^ "European Union Bans formaldehyde/formalin within Europe" (PDF). European Commission's Environment Directorate-General. 22 June 2007. pp. 1–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2013.

- ^ "ESIS (European Chemical Substances Information System)". European Commission Joint Research Centre Institute for Health and Consumer Protection. February 2009. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ "S.1660 - Formaldehyde Standards for Composite Wood Products Act". GovTrack. 25 August 2010. Archived from the original on 29 April 2019.

- ^ "Formaldehyde Emission Standards for Composite Wood Products". Regulations.gov. United States Federal Register. 12 December 2016. Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

The emission standards will be 0.05 ppm formaldehyde for hardwood plywood, 0.09 ppm formaldehyde for particleboard, 0.11 ppm formaldehyde for medium-density fiberboard, and 0.13 ppm formaldehyde for thin medium-density fiberboard.

- ^ "Health Canada - Proposed residential indoor air quality guidelines for formaldehyde". Health Canada. April 2007. Archived from the original on 2013-05-30.

- ^ "View Rule". www.reginfo.gov. Archived from the original on 2023-10-20. Retrieved 2023-10-21.

- ^ "Formaldehyde-laced foods reemerge in Indonesian markets". antaranews.com. 2011-08-10. Archived from the original on 2018-10-25.

- ^ "Formaldehyde-Tainted Rice Drinks Found at Carrefour Markets". Jakarta Globe. 2011-08-22. Archived from the original on 2012-09-28.

- ^ "BPOM Uncovers Two Formaldehyde-Tainted Noodle Factories in Bogor". Jakarta Globe. 2014-10-12. Archived from the original on 2015-08-01.

- ^

- Tang, Xiaojiang; Bai, Yang; Duong, Anh; Smith, Martyn T.; Li, Laiyu; Zhang, Luoping (2009). "Formaldehyde in China: Production, consumption, exposure levels, and health effects". Environment International. 35 (8): 1210–1224. Bibcode:2009EnInt..35.1210T. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2009.06.002. ISSN 0160-4120. PMID 19589601.

- see references cited on p. 1216 above

- "Municipality sees red over bad blood processing". China Daily. 2011-03-18. Archived from the original on 2018-10-24.

- ^ Blum, Deborah, 1954- (2018-09-25). The poison squad: one chemist's single-minded crusade for food safety at the turn of the twentieth century. Go Big Read (Program). New York, New York. ISBN 9781594205149. OCLC 1024107182.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Was Death in the Milk?". The Indianapolis News. 1900-07-31. p. 5. Archived from the original on 2018-11-17. Retrieved 2014-08-20 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Wants New Law Enacted. Food Inspector Farnsworth Would Have Use of Formaldehyde in Milk Stopped". The Topeka Daily Capital. 1903-08-30. p. 8. Archived from the original on 2018-11-17. Retrieved 2014-08-20 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Illegal business 'being run by a gang'". The Nation. 2011-06-16. Archived from the original on 2011-06-16.

- ^ "Import of formaldehyde fish from Pakistan foiled in Batam". The Jakarta Post. 2012-02-23. Archived from the original on 2018-12-16.

- ^ "Trader Fined for Selling Fish Treated with Formalin". The Daily Star. 2009-08-31. Archived from the original on 2019-04-29.

- ^ "Formalin Control Bill 2015 passed". ntv online. 2015-02-16. Archived from the original on 2018-03-23. Retrieved 2015-03-04.

- ^ Meadows, Michelle (January 2006). "A Century of Ensuring Safe Foods and Cosmetics" (PDF). FDA Consumer. 40 (1): 6–13. PMID 16528821.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Formaldehyde is classified as a carcinogen, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), and U.S. National Toxicology Program.[15]

External links

[edit]- International Chemical Safety Card 0275 (gas)

- International Chemical Safety Card 0695 (solution)

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0293". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Entry for "Formaldehyde" on the Australian National Pollutant Inventory

- Formaldehyde from ChemSub Online

- Prevention guide—Formaldehyde in the Workplace (PDF) from the IRSST

- Formaldehyde from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

- IPCS Health and Safety Guide 57: Formaldehyde

- IPCS Environmental Health Criteria 89: Formaldehyde

- SIDS Initial Assessment Report for Formaldehyde from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

- "Formaldehyde Added to 'Known Carcinogens' List Despite Lobbying by Chemical Industry"—video report by Democracy Now!

- Do you own a post-Katrina FEMA trailer? Check your VIN#

- So you're living in one of FEMA's Katrina trailers... What can you do?

- Formaldehyde in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)