Mission Point (Mackinac Island)

Mission Point | |

|---|---|

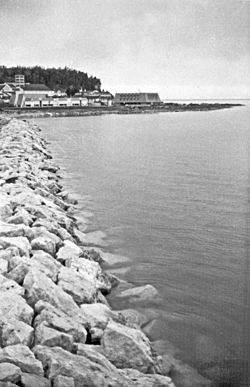

This jetty is the western boundary of Mission Point. Looking east, this 1969 view shows the Mackinac College campus, with the Peter Howard Memorial Library and Clark Center. The eastern boundary of Mission Point, Robinson’s Folly, is in the background. | |

![Map of Mackinac Island, MI, by Morgan H. Wright, E.M., Marquette, MI.[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2f/HM1_MI_p506_fold-out.jpg/250px-HM1_MI_p506_fold-out.jpg) Map of Mackinac Island, MI, by Morgan H. Wright, E.M., Marquette, MI.[1] | |

| Coordinates: 45°51′02″N 84°36′24″W / 45.8506°N 84.6067°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Michigan |

Mission Point is located on the southeast side of Mackinac Island, Michigan. It is approximately 21 acres (8.5 ha) in size[2] between Robinson's Folly and the jetty terminating near Franks Street. The Island has a history of documented European development beginning with French Jesuit missionaries landing at the point in 1634, less than two decades after the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock on the East Coast of North America.[3]

Since that time, development at Mission Point has included a Mission House, summer house, several summer Victorian cottages, conference center for an international group, theater, film studio, college campus, and vacation resort. Mission Point looks out toward Round Island (Michigan) over the Straits of Mackinac, the principal waterway between Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. In the early 21st century, Mission Point has been developed as Mission Point Resort, a full-service facility including guest lodging, three restaurants, putting greens, a museum, and a theater.[4]

Prehistory of Mackinac Island

[edit]For millennia before the arrival of Europeans, Mackinac Island was home and meeting place for Chippewa (Anishinaabeg), Huron, Menominee, Potawatomi, Ojibwe, Ottawa, and other Native American Indian tribes. They enjoyed aurora borealis displays, pure fresh water, ice-locked winters, quiet snow storms, spring trees and birds, pleasant summers, and autumn leaves. These were described in a reminiscence by an Indian chief: “Great Spirit allowed a peaceful stillness to dwell around thee, when only light and balmy winds were permitted to pass over thee, hardly ruffling the mirror surface of the waters that surrounded thee; or to hear by evening twilight, the sound of the Giant Fairies as they, with rapid step and giddy whirl, dance their mystic dance on thy limestone battlements. Nothing then disturbed thy quiet and deep solitude but the chippering of birds and the rustling of the leaves of the silver-barked birch.”[5][6] Jean Nicolet and Father Barthélemy Vimont were the first Europeans known to pass through the Straits of Mackinac (1634–1635). They were guided there by a small group of Huron Indians 14 years after the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock. Other French colonists had settled in eastern Quebec. In 1642, Fr. Vimont documented the trip in ‘The Jesuit Relations’ (Relations des Jésuites de la Nouvelle-France).[3] Near Mackinac Island, Nicolet and his companions encountered members of the peaceful Ho-Chunk Nation (Winnebago Tribe).[7]

Jesuit fathers Charles Dablon and Jacques Marquette founded Catholic missions on Mackinac Island, St. Ignace, and Mackinaw City. Fr. Dablon built a birchbark chapel on Mackinac Island in 1670. In 1671 Fr. Jacques Marquette moved the mission to St. Ignace on the Upper Peninsula. Thereafter it was transferred to Mackinaw City. The British took it over in 1763, after defeating the French in the Seven Years' War - their government ceded their territories in North America east of the Mississippi River to the British.

Finally, in 1780 the mission was relocated to Mackinac Island, where the British had purchased property from the Indians for £5,000. Fort Mackinac was also moved from the mainland to the Island, and Major Sinclair became its first commander. That winter the associated town residents relocated to the Island, becoming the first permanent "white" settlement on Mackinac Island.[9][10]

Mission Point development

[edit]Robinson’s Folly (1780s)

[edit]In 1782 British Captain Daniel Robertson (1733–1810) became the commander of Fort Mackinac. Captain Robertson built a small summer house on a high limestone outcropping less than a mile away from the Fort at the southeast corner of the island (today's Mission Point). This little building was the first recorded structure at Mission Point. It was frequented by Robertson, his son, and fellow officers. Reportedly, no hospitality or entertainment there was complete without pipes, cigars, and wine. Robertson was served by his household slaves, Jean and Marie-Jean Bonga. Among their children was Pierre Bonga, who became a noted fur trader with the British Northwest Company and later with the American Fur Company. Robertson freed these slaves when he was reassigned from Fort Mackinac. They stayed and the parents opened a small hotel.

Robertson commanded Fort Mackinac through 1787, when he left for a posting as major in the British army in Montreal, Quebec. Eventually he became a colonel in the army and amassed 5,000 acres in land grants for himself and his four children. After some years the cliff collapsed, dropping the summer house 127 feet down to the road and lake below. The remaining blunt, precipitous cliff came to be called ‘Robertson’s Folly’ and later (for unknown reasons) Robinson's Folly. Many tales have been attached to the site.[6][11] This part of Mission Point is the easternmost point of the Island.

Mission House (1825)

[edit]See also Mission House (Mackinac Island)

Christian missions were often the first outposts of European colonization of the North American frontier. The United Foreign Missionary Society founded a Protestant mission on Mackinac Island in 1822.[13] The objective was to train Indian youth as teachers of English, Christianity and majority American ways, and as interpreters. To support this mission, the US government transferred 12 acres at the southeast end of the island to the Society.[13] The Connecticut Missionary Society sent Rev. William Montague Ferry to the island, and he opened the school with twelve Indian children on November 3, 1823. He was assisted by his wife Amanda White Ferry and Elizabeth McFarland. The school building was framed and enclosed by workers from Detroit, using timbers obtained from a sawmill on Mill Creek (6 mi SE of current day Mackinaw City). By 1825, construction of the 2-story ‘Mission House’ was completed by Martin Heydenburk, one of the school's teachers. Because the island had no Protestant church, the east wing of Mission House was fitted with a movable partition so that on Sundays it became a chapel. Enrollment soon averaged 150 Native American pupils per year with >100 receiving free board, room, and clothing from the mission family. The southeast point of Mackinac Island became known as Mission Point.[14][1]

Designed as a residence and boarding school, Mission House was also home for the mission families. Pupils at the school were gathered from tribes around the upper Great Lakes and headwaters of the Mississippi, as well as from more than 1000 miles away. A total of more than 500 Indian girls and boys plus children of mission families were educated at the school. The area was a peaceable gathering place for many tribes, with as many as 1500–2000 individuals trading and engaging in friendly companionship. Mackinac Island was also the headquarters of John Jacob Astor's monopoly, the American Fur Company.[14]

Mission House operated successfully for a decade. After the American government began deporting some of the tribes to reservations west of the Mississippi River in the 1830s, the school had difficulty recruiting students. In 1834 Rev. Ferry moved to Grand Haven, MI and, in 1836, the missionary society sold the acreage at Mission Point. Astor retired from the fur trade to invest in New York City real estate to great success. In the later 19th century, European-American visitors began using the island as a summer resort. The mission was formally given up in 1837 when the State of Michigan was admitted to the United States.[14] Edward Franks bought the unused Mission building in 1845, added a third story, and reopened it as Mission House Hotel in 1849.

Mission House was owned and operated by the Franks family until 1939. They sold it and the hotel was converted to a rooming house. In 1946 the Hon. Miles and Margaret Phillimore bought the property, and provided quarters for summer visitors at Moral Re-Armament meetings. In 1965 it was deeded to Mackinac College (1966–1970) and used as a ski hut. After Mackinac College closed in 1970, it was briefly owned by the Cathedral of Tomorrow. In 1977, Mission House was acquired by Mackinac Island State Park, which restored it and uses it to house summer employees of the park.[14][15]

Small Point and Cedar Point cottages (1882)

[edit]

In 1882, Alanson Sheley (1809–1892) had two cottages built on Mission Point east of the Mission House (then the Mission House Hotel). A cottage was built by Robert Doud; today's Mission Point Theater was built to the west of its site (below). The second was Cedar Point cottage, located in the courtyard just northeast of today's Great Hall (below). When Sheley died, Cedar Point cottage, which had served as a summer cottage for the family, went to the Brooks family. The cottage built by Doud went to the Clark family, who later sold it to the Faren family, when it became known as the Faren Cottage.[16][17] In 1948, Rev. Norman Schwab purchased Faren Cottage. He had recently sold his family's Small Point home in Maine, and called the cottage Small Point.[18] Small Point became the family's principal residence year round. In 1959, the Schwab family donated the land on which their cottage stood to the Moral Re-Armament (MRA) group. It planned to use the land for construction of a film studio. The cottage was winterized and transported to a site west of Robinson's Folly. Small Point cottage served as a residence for the Schwab family and several other families for many years. In 1971, John and Lois Findley moved to Mackinac Island to teach at the local school. They rented Small Point and purchased it in 1973. They operate Small Point as a bed and breakfast.[18][19]

Cedar Point cottage was constructed in 1882 on Mission Point. It was occupied seasonally during the summer especially by wealthy families from Detroit. and was occupied through subsequent years: —1917, Mr. and Mrs. Walter Brooks and Mr. and Mrs. Alanson Brooks of Detroit arrived Sunday to look over the improvements being made by Contractor Doud on their beautiful summer cottage on Cedar Point.[20]—1917, Mr. David Whitney Jr. and family of Detroit arrived Wednesday and are occupying the Brooks cottage located at Cedar Point[21]—1918, Brooks, Alanson S. (Zaidee Hubbard); Brooks, Stanley (Louise B. Patterson) ‘Cedar Point Cottage’, Mackinac Island MI.[22]

In the early 1950s MRA obtained the land on which Cedar Point cottage was located. An aerial photograph from 1955/1956 shows Cedar Point cottage in the midst of the construction of the Great Hall Complex. This photograph is on display in the MRA Exhibit, which is located on the fourth floor of the former film studio (below) at Mission Point Resort. Cedar Point cottage was later demolished.

A third cottage owned by Jimmie Francis was also located at Mission Point. This cottage was between the Studio and the Great Hall complex (below). In late 1965 it was torn down. The site was excavated with the intent to build a thrust stage theater. This theater was not built. Eventually an outdoor swimming pool was constructed on the site.

1915 map

[edit]In 1915 Mackinac Island was mapped by Morgan H. Wright, E. M. of Marquette, MI (copyright Edwin O. Wood, 1915). Identified by name on the map are both Robinson's Folly and Mission Point. Along the Mission Point shoreline, the south-south-east shore is labeled Ferry Beach and the east-south-east shore is labeled Peshtigo Beach. This map also shows the jetty leading to present-day Frank's Street at the west end of Mission Point. Comparing this map with a present-day Google Maps image, the field at Mission Point has apparently doubled in size due to the deposition of excavated limestone from building construction on the Point.[1]

MRA arrives (1942)

[edit]In 1942, a multi-national group, friends of the Moral Re-Armament (MRA), led by Dr. Frank N. D. Buchman began meeting together on Mackinac Island. As the number of guests increased, they rented the dilapidated Island House hotel for $1; they renovated it as a conference center. In subsequent years, friends of MRA purchased and restored numerous cottages and homes on the island, including: Mission House (Miles Phillimore), Mapleview (Harold Sack), Small Point (‘Faren Cottage,’ Norman Schwab),[18] Vrooman Cottage (Lee Vrooman), Stonecliffe, Bennett Hall, Chateau Beaumont, Pine Cottage, La Chance, Reid House, Eastman Building, Webster House, and Bonnie Doone. Thousands of MRA conference visitors came to the island each summer. Their business provided employment for island residents but also crowded regular summer tourists. After deliberations with the island's City Council, MRA representatives eventually agreed that they would confine MRA development to the eastern end of the island.[23] In 1952 MRA began developing the Mission Point cottages and property.[19]

They began with raising a tent near the Cedar Point and Faren cottages. In the summer of 1952, it was replaced with an open-sided shed. This was called Cedar Lodge and served as a temporary conference and dining hall. By the summer of 1953, the lodge was walled in, using timbers cut from the Stonecliffe property. Later this was the first building around which the Great Hall complex was built (below).[19]

Mission Point Theater (1955)

[edit]

Groundbreaking ceremonies at Mission Point were held by the MRA in October 1954, when 150-year-old Norway pine logs were cut and brought in from nearby Bois Blanc Island. Island resident Charles Francis was foreman of the construction crew. The logs were towed across the stormy waters of Lake Huron and floated onto the Mission Point shore before the straits froze for the winter. They were trimmed into 60-foot roof trusses for the Mission Point Theater. In addition, 45 tons of native stone were brought in by boat for building and fireplace construction. Other construction materials were stockpiled on the island. During the winter, supplies were carried across the ice by motor sled or horse-drawn sleigh, or flown to the island by four-seater plane and transported on a horse-drawn carriage to Mission Point. The work provided year-round employment for island residents and MRA volunteers. Initially a sturdy old barn (the Curry Barn) located between the Theater and Faren Cottage was attached to the east side of the Theater. The completed 14,696 ft2[24] Mission Point Theater seated 575 and was dedicated on June 4, 1955. In 1959, when plans were made to build a studio, the barn was put on wheels and relocated to the west side of the Theater. It was attached to the side of the stage and fly gallery, and integrated into the structure of the completed Theater.[15][19]

In 1965 MRA deeded the theater to Mackinac College, an institution legally independent of MRA and chartered by the Michigan Board of Education.[25][26] Professors and students at the college used the theater for drama and music classes and performances.

When Mackinac College closed in 1970, TV evangelist Rex Humbard purchased the building. He incorporated it into his new, nondenominational Bible college. Subsequently, he began using the theater and other buildings as a vacation resort.

In 1977 Humbard sold the property. The theater was part of the newly named Mackinac Hotel and Conference Center. In late 1987 the theater was sold to John Shufelt, and in 2014 to Dennert O. and Suzanne Ware.[27] It is now used as the Center for the Arts at Mission Point Resort and operated by the Mackinac Arts Council.[28] It screens mainstream movies from May through October, showing films every evening.[29][30][31]

Great Hall Complex (1956)

[edit]

In the winter of 1955, immediately after construction of the Theater, MRA workers began building the Great Hall complex at Mission Point (64,732 ft2[24]). It was to serve as a convention center and residence hall for summer MRA meetings. It surrounded Cedar Point cottage and included a tepee-shaped Great Hall, lobbies, porches, kitchens, dining rooms, meeting rooms, and residence halls (48,330 ft2[24]) named “building A” and “building B” (250 beds in 150 rooms). Cedar Point cottage was eventually torn down, and the Great Hall complex was dedicated on September 24, 1956. A three-story connector between buildings A and B was added during the winter of 1958. Many of the floors of the Great Hall complex are heated, and the complex accommodates 1000 people.[15]

The Great Hall complex is the largest single indoor space on Mackinac Island. It was constructed by 210 tradesmen from Mackinac Island and across Michigan. The teepee-shaped Great Hall features 51-foot logs cut from one of the last stands of virgin Norway pine in the Tahquamenon Falls State Park in Michigan's Upper Peninsula. The structure was designed by architect, William Woollett; its 16 log trusses converge at a height of 36 feet (11 m). The floor space equals approximately 7000 ft2.[24] A globe of the world was affixed in the peak.[15][19]

Construction began with the delivery of 3000 tons of supplies and equipment in 1955 before the straits froze for the winter. People on the project said that construction nearly came to a standstill in March 1956, when lumber had been used and the straits were still locked in ice. Over a relatively warm weekend, the wind blew ice clear of the main channel between the island and the mainland. Workers dynamited ice in the shipway, the 36-inch-thick ice by the mainland was sawed through, the sun shone, the ice gave, and the supply barge Beaver, manned by a volunteer crew, broke through to Mission Point. Over 24 hours, 100 tons of lumber and other materials were brought out to Mission Point. Soon ice began to form again, but with the additional supplies, the construction continued to completion.

In the spring, the Stouffer's Corporation provided furniture for the dining rooms, Lee Carpets supplied extensive wall-to-wall carpeting, and Mackinaw City's stonemason Friedrich Grebe built the fireplaces and much of the landscaping stonework.[32][33] In 1956 after the Great Hall complex was completed, Woollett reportedly learned an Indian legend about the Great Tepee from an islander. This legend said that the Great Spirit would one day gather nations under a great tepee, or wigwam, and together they would find the secret of peace. This story is consistent with reminiscences of people who were present at the time. It is also consistent with a newspaper report in which Howard Santigo, grandson of a Mackinac Island Chippewa Indian chief, recounted this same legend of the Great Spirit.[2] In 1893, D.H. Kelton related a similar tale in which the ‘suffering ones’ of every race and clime would be invited to draw their canoes up onto the eastern shore of Mackinac Island, pass through Arch Rock, and meet in a wigwam built of the tallest trees (home of the great spirit Gitche Manitou). This tale was repeated by E. O. Wood, who suggested in 1918 that the wigwam was transmuted into Sugar Loaf rock.[34][35] Every spring and summer for a decade after its construction, the Great Hall complex attracted thousands of MRA conference delegates from the US, Asia, Africa, and Europe.[15][19] Then, in 1965, the Great Hall complex was deeded over to Mackinac College, an institution legally independent of MRA and chartered by the Michigan Board of Education. From 1966 to 1970 the College was in operation and the Great Hall complex was used year-round. Graduation ceremonies for the Charter Class students at the college were held there in June 1970.[26][36][37]

After Mackinac College closed in 1970, TV evangelist Rex Humbard purchased the Great Hall complex for use as part of a nondenominational Bible college (Mackinac College (Humbard)). In 1977 he sold the property, which became the Mackinac Hotel and Conference Center. In late 1987 it was sold to John Shufelt, and in 2014 to present the owners, Dennert O. and Suzanne Ware.[27][29]

West Residence (Straits Lodge) (1957)

[edit]

The West Residence (112,300 ft2,[24] now called the Straits Lodge) was constructed by MRA workers in 1956–1957 to expand lodging for MRA summer conferences. Residence architect William Woollett was friends with the owner of the Mackinac Island Grand Hotel, W. S. Woodfill. He knew that Woodfill was proud of owning “the largest porch in the world” (660 ft). So out of friendship for him the West Residence was designed to be one foot shorter than the porch of the Grand Hotel. It has 400 beds in 225 rooms. The completed three-story West Residence was finished with brick and limestone, having a two-story high entryway with a five-foot (1.5 m) marble-paneled fireplace (Johnson Hall). The Residence accommodated many thousands of conference visitors in the decade after it opened.

In 1965 the West Residence was deeded over to Mackinac College, an institution legally independent of MRA and chartered by the Michigan Board of Education.[26][38] From 1966 to 1970 the college used the building as the men's dormitory. The basement of the Residence housed the college switchboard, photographic darkroom, laundry, finance offices, and administrative offices. After Mackinac College closed in 1970, TV evangelist Rex Humbard purchased the building for use as part of a nondenominational Bible college. In 1977 Humbard sold the property and it became part of the Mackinac Hotel and Conference Center. In late 1987 it was sold to John Shufelt, and in 2014 to present owners Dennert O. and Suzanne Ware.[27] Currently called the Straits Lodge, it has been painted white.[29]

Film Studio-Fine Arts building (1960)

[edit]

The Film Studio-Fine Arts Building (86,287 ft2[24]) was constructed by 250 workers from many countries who volunteered their services to MRA. At the time it was built, the Studio had the second largest sound stage in the world and the second largest television studio in America. A United Press International reporter claimed that the saga of its building was “the greatest news story of our age.” MRA constructed the Studio to accommodate filming and processing of its movies and television programs. Quantities of materials and technological aid were donated by RCA, Kliegl Brothers Universal Electric Stage Lighting Company, Clancy Stage Rigging, and others. The sound stage (80 ft. x 120 ft.) was poured in one all-night mid-winter session.[15][19]

The studio building contains two major sound stages, rooms for rehearsal, music, orchestra, costume designing, sewing, storage, set design, props, hairdressing, make-up, dressing, art, and sound mixing. In the 1960s these rooms were fully furnished, in addition to a huge costume department, lighting switchboard, laboratories for film processing and editing, and construction shops. The studio has a 108 ft. glassed-in tower that from 2013 until 2016 was the Mission Point historical museum.[39]

Movies that were filmed and produced in the Studio include The Crowning Experience (MRA), Decision at Midnight (1963, MRA), Voice of the Hurricane (1964, MRA), and Somewhere in Time (1980, Universal Pictures). In summer 1965 the Studio's sound stage was the site for original performances of the musical show Sing-Out ’65, when ~7,000 young people from around the world were meeting for summer MRA conferences.[40] Seating was brought in for audiences of ~1000 at the weekly Sing-Out shows. In the fall of 1965 the cast of the show began traveling throughout the US and Asia. In 1966, Sing-Out changed its name to Up With People and expanded into several international musical casts emphasizing personal change that could lead to social, economic and political change.[19][41] In late 1965 the Studio was deeded over to Mackinac College, an institution legally independent of MRA and chartered by the Michigan Board of Education.[26][42] The intent was that the many floors and rooms of the Studio would provide classroom and library space for the college. The island’s fire marshal, however, did not approve this use, so the studio served as a Fine Arts Center for the college.[43] The sound stage was then converted into a gymnasium that the College shared with Island school children for sports.

After Mackinac College closed in 1970, TV evangelist Rex Humbard purchased the Studio and other buildings to use for religious education. In 1977 Humbard sold the property. For the 1979 summer season, Universal Studios leased the sound stage to produce the motion picture Somewhere in Time starring Christopher Reeve and Jane Seymour. The entire cast and crew of the movie were hosted by “The Inn on Mackinac,” then owners of the Mission Point property. In late 1987 the property was sold to John Shufelt, and in 2014 to present owners Dennert O. and Suzanne Ware.[27][29]

Peter Howard Memorial Library (1966)

[edit]Use of the Studio as a library and classroom building had been disallowed by the Mackinac fire marshal,[44] so construction of a library for Mackinac College (1966–1970) was a priority. In the fall of 1965 a $1,500,000 gift[2] from Mr. and Mrs. W. Van Alan Clark (hon. Chairman of Avon Products, Inc.) jump-started planning for the Peter Howard Memorial Library (capacity 100,000 books; 36,000 ft2[24]), named for the British journalist, playwright, and author who was (briefly) head of MRA (born 1908 – died 1965). The lawn just south of Huron Street at Mission Point was chosen as the site for the library. In 1964-65 the lawn had been a playing field for athletic games at summer MRA conferences.

The library was designed by Edwin B. Cromwell of Ginocchio, Cromwell Associates, Little Rock, Arkansas. The construction crew included men from the U.S., Canada, Japan, and other countries (see details in Clark Conference Center, below). It was a three-story building with an overhanging roof canopy and elongated dormer windows; on the 3rd floor these windows provided long views of Lake Huron and Round Island. Icicles hung from the roof in the winter. In 1966 when Mackinac College opened its doors, over 10,000 books were stocked in the library. In addition to books, stacks, and book repair areas, the 3-story library provided classrooms, language labs, and study areas.[45] When Mackinac College closed in 1970, the books were donated to Lake Superior State College (now University). Through disuse, the library fell into disrepair due to leakage and mildew. It was situated along the shoreline, where cycling of the Great Lakes’ water levels had previously created a freshwater marsh in this area. By 1970 the water table was rising into the basement.[46] Due to these problems, the building was torn down between 1990 and 1992.[2][47]

Clark Conference Center for the Arts and Sciences (1968)

[edit]

By 1967, Mackinac College (1966–1970) at Mission Point needed conference rooms, science labs, and more classrooms. This led to the construction of the Clark Center for the Arts and Sciences (81,057 ft2[24]), which was also designed by Edwin B. Cromwell. It was paid for by donations from Mr. and Mrs. Van Alan Clark (hon. Chairman of Avon Products, Inc.). Construction supervisors reported that the Clark Center and the Peter Howard Library were built by more than 325 volunteer workers from 13 different countries. Room, board, and travel expenses for these workers were covered by the college. Included were 115 Native Americans from tribal groups across the United States and Canada. Twenty-four volunteers came from South Korea, 16 from Japan, 9 from Denmark, 8 from Jamaica, 7 from Indonesia, 2 from Finland and 1 each from Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland and Trinidad and Tobago. Some were skilled tradesmen who trained others in the skills of their trades. Many reported that living and working with others from such diverse backgrounds developed their respect for cultural, racial and national differences. Some eventually became students at the college.

Construction of the Clark Center continued through the fall and winter of 1967, and the building was ready for use in Mackinac College's third academic year, September 1968. Located directly in front of the Theater and Fine Arts Building, the Clark Center's 18-inch-thick concrete roof supports a carriage driveway leading from the Mission House and West Residence buildings to the Great Hall. This rooftop plaza commands a sweeping view of playing fields and the Straits of Mackinac. During the college years, the building included 30 classrooms, laboratories, offices, lounges, a 300-seat lecture-recital hall, and a 150-seat natural science demonstration room.

The Clark Center featured prominently in the 1970 graduation ceremonies for the Charter Class of Mackinac College. In 1971 the building was sold with the rest of the campus to TV evangelist Rex Humbard. In 1977 Humbard sold the center and other campus property to the Mackinac Hotel and Conference Center. In late 1987 it was sold to John Shufelt with the rest of the campus, and in 2014 to Dennert O. and Suzanne Ware;[27] it has been adapted as the Mission Point Resort.[15][19]

Mission Point Resort (since 1987)

[edit]Major changes were made after the Mackinac Hotel and Conference Center was purchased by John Shufelt in 1987. The name was changed from The Mackinac Hotel and Conference Center to Mission Point Resort, a nod to the history of that area as home to Mission Church and Mission House. Mission Point Resort's vision was to create a welcoming, inspiring, and relaxing atmosphere for guests. Derelict buildings were converted into more functional and visually appealing spaces. The Howard Library was torn down to create the Front Lawn, which is now home to the gazebo and Mission Point's Adirondack lawn chairs. A number of restaurants were added, including Chianti, Round Island Bar & Grill, and Bistro on the Greens.[citation needed]

The resort's theater has been renamed the Center for the Arts, which now hosts movie showings, art exhibits by local artists, and numerous craft workshops. This is in collaboration with the Mackinac Arts Council, Mackinac Island's non-profit arts agency.[49]

Mission Point is also a wedding and conference destination. The resort is open from early May through the end of October and reopens for several days around New Year's Eve.

Mission Point Resort was purchased in 2014 by Dennert O. and Suzanne Ware of San Antonio, Texas, who also own Silver Birches on Mackinac Island. The Wares are planning a multimillion-dollar property-wide upgrade over the next few years that will include an expanded spa and pool complex and guest room improvements.[50]

1986 water treatment plant

[edit]The Mackinac Island Water Treatment Plant is located east of Mission Point and Robinson's Folly on the shoreline. It supplies potable water to nearly everyone on the Island. It is on former Mackinac Island State Park property deeded to the City of Mackinac Island, and was built in 1985/1986. This plant replaced the “Power House” pumping station north of the Arch Rock. The plant uses membrane microfiltration to filter water from Lake Huron and is rated at 2.7 million gallons per day.

Representation in other media

[edit]- Edward Everett Hale published a story called “The Man Without a Country" (1863); it opened with the sentence: “I was stranded at the old Mission House in Mackinaw, waiting for a Lake Superior steamer which did not choose to come.”

See also

[edit]- Mackinac College, a private liberal arts college

- Mackinac College (Humbard), a Christian-based college at the Rex Humbard Development Center

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Wood, Edwin O. (1918). Historic Mackinac. Vol. 1 (of 2). New York: The Macmillan Company. p. 506 fold-out.

- ^ a b c d McBride, Marian (October 5, 1966). "New Idea in Old Setting". Milwaukee Sentinel. pp. 3, 6.

- ^ a b "(4) Chapter First: Of the Residence at Quebec, and the State of the Colony". The Jesuit Relations. Vol. XXIII. 1642. pp. 275–277. Archived from the original on January 29, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ "Mission Point Resort". Mission Point Resort. Retrieved September 17, 2014.

- ^ "History & Culture". Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Robinson, G.; Sprague, R. A. (1873). "History of Cheboygan and Mackinac Counties". Michigan Genealogy on the Web. USGenWeb Project. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Straus, Frank (June 30, 2007). "Jean Nicolet Was Little Known Explorer of Upper Great Lakes". Mackinac Island Town Crier. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Wood, Edwin O. (1918). Historic Mackinac. Vol. 1 (of 2). New York: The Macmillan Company. facing-page 367.

- ^ Kelton, Dwight H. (1883). "Early Officers At The Fort Michilimackinac and Mackinac". GenWeb. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Straus, Frank (May 27, 2005). "Jesuit Ties to Mackinac Island Now More Than 3 Centuries Old, Jesuit Missionaries A Look at History". Mackinac Island Town Crier. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Kelton, Dwight H. (1893). Annals of Fort Mackinac. Mackinac Island: John W. Davis & Son. pp. 57–60. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Wood, Edwin O. (1918). Historic Mackinac. Vol. 2 (of 2). New York: The Macmillan Company. facing-page 345. Drawing title is from an old print appearing in Quarterly Paper of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, No. XX. 1835

- ^ a b Wood, Edwin O. (1918). Historic Mackinac. Vol. 1 (of 2). New York: The Macmillan Company. p. 399.

- ^ a b c d Williams, Meade C. (1895). The Old Mission Church of Mackinac Island: An Historical Discourse Delivered at the Reopening, 28 July 1895. pp. 5–22. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g "National Historic Landmark Nomination Mackinac Island, amended January 2000" (PDF). Rev. 8-86 OMB No. 1024-0018. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ "Margaret Goodenough VanDusen, Died Thursday, August 18, 2011". Obituaries. Grosse Pointe News. August 18, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ "For the Record..." Mackinac Island Town Crier. December 9, 2006. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Small Point Bed and Breakfast". Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hadden, Frances Roots (1973). The Story of Mission Point, The College Buildings. IOFC. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ "Thursday, May 24, 1917". Looking Back. Mackinac Island Town Crier. May 26, 2007. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Schlehuber, Ryan (July 14, 2007). "Thursday, July 12, 1917". Looking Back. Mackinac Island Town Crier. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ "Detroit Summer address where it differs from the winter address". Social Register. New York City: Social Register Association. 1918. p. 602. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Martin, Morris (2001). Always a Little Further. Tucson, Arizona: Elm Street Press. p. 119.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Woods, R. M (1970). A Complete $13,000.000 physical Plant with today's finest training and educational aids, for sale at far less than cost (Real estate brochure). New York: Previews Inc. International Real Estate Marketing Service. Listing No. 75288.

- ^ Martin, Morris (2001). Always a Little Further. Tucson, Arizona: Elm Street Press. pp. 203–204.

- ^ a b c d Sack, Daniel (2009). Moral Re-Armament. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 186.

- ^ a b c d e "Mission Point Resort Is Sold". Mackinac Island Town Crier. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- ^ "Mackinac Arts Council". Mackinac Arts Council. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "History". Mission Point Resort. Archived from the original on March 30, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Mackinac Arts Council". Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ "Movie Theater at Mission Point Resort Mackinac Island". www.missionpoint.com. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- ^ Hunter, Willard (1956). Mackinac Island of Renaissance (Film). Moral Re-Armament.

- ^ "Thursday, August 9, 1956". Looking Back. Mackinac Island Town Crier. August 12, 2006. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Kelton, Dwight H. (1893). Annals of Fort Mackinac. Mackinac Island: John W. Davis & Son. pp. 67–70. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Wood, Edwin O. (1918). Historic Mackinac. Vol. 2 (of 2). New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 68–72.

- ^ "Environmental School Hopes to Take over College; ...29 Degrees Conferred by Loyal President". Mackinac Island Town Crier. July 4, 1970.

- ^ Martin, Morris (2001). Always a Little Further. Tucson, Arizona: Elm Street Press. p. 204.

- ^ Martin, Morris (2001). Always a Little Further. Tucson, Arizona: Elm Street Press. pp. 203–204.

- ^ "Mission Point - Observation Tower". Mission Point Historical Museum. Archived from the original on June 20, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- ^ McGee, Frank (2007). A Song for the World. Santa Barbara: Many Roads Publishing. p. 2.

- ^ Allen, David B.; Hoar, Robin; Everson, Karin, eds. (1966). How to create your own Sing-Out. Los Angeles: Pace Publications. pp. 94–101.

- ^ Martin, Morris (2001). Always a Little Further. Tucson, Arizona: Elm Street Press. pp. 203–204.

- ^ Martin, Morris (2001). Always a Little Further. Tucson, Arizona: Elm Street Press. p. 210.

- ^ Martin, Morris (2001). Always a Little Further. Tucson, Arizona: Elm Street Press. pp. 206, 210.

- ^ "Students of Mackinac College". The Mackinac View. Mackinac College. 1967.

- ^ "NOAA Great Lakes Water Level Dashboard". Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ "Mackinac College Webline".

- ^ "Mackinac College". Mackinac Parks.

- ^ "Mackinac Arts Council". Mackinac Arts Council. Retrieved September 17, 2014.

- ^ "Mackinac Island resort changes hands". MLive.com. December 16, 2014. Retrieved October 24, 2015.