Minqaria

| Minqaria Temporal range: Late Maastrichtian,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Neornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ornithopoda |

| Family: | †Hadrosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Lambeosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Minqaria Longrich et al., 2024 |

| Species: | †M. bata

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Minqaria bata Longrich et al., 2024

| |

Minqaria (meaning "beak") is a genus of arenysaurinin lambeosaurine hadrosaur from the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Ouled Abdoun Basin of Morocco. The genus contains a single species, M. bata, known from a partial skull.[1]

Discovery and naming

[edit]

The Minqaria holotype specimen, MHNM.KHG.1395, was discovered in sediments of the Oulad Abdoun Basin (upper Couche III, Sidi Chennane locality) of Morocco. The specimen consists of a partial skull, including a right maxilla, left dentary, and braincase.[1]

In 2024, Longrich et al. described Minqaria bata as a new genus and species of arenysaurin hadrosaurid based on these fossil remains. The generic name, "'Minqaria", is Arabic for "beak". The specific name, "bata", is Arabic for "duck".[1]

Description

[edit]

Minqaria is estimated to have a length of about 3.5 metres (11 ft) long and a weight of 250 kilograms (550 lb), similar in size to its contemporary relative Ajnabia. Since the braincase bones are fused, the Minqaria holotype likely belonged to a mature specimen, despite its small size. It can be differentiated from other arenysaurins, including Ajnabia, in several features of its crania and teeth.[1]

Classification

[edit]

Longrich et al. (2024) placed Minqaria in a phylogenetic analysis and found it to belong to the hadrosaurid clade Arenysaurini, in a clade containing Ajnabia, also known from the Ouled Abdoun Basin, and other Moroccan lambeosaurines; they are linked in their phylogenetic analysis by a single biogeographical character. Their cladogram is shown below:[1]

| Lambeosaurinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Palaeoecology

[edit]

The holotype specimen was recovered from the phosphates of the Ouled Abdoun Basin of north-central Morocco. The phosphates are a nearshore marine environment, dominated by sharks, fish, mosasaurs, and other marine reptiles. Dinosaurs are less common, however, but include at least three hadrosaurids including fellow arenysaurin Ajnabia, the large abelisaurid Chenanisaurus barbaricus, two other potentially distinct abelisaurids of smaller size, and an unnamed titanosaurian.[2][3][4] Moroccan lambeosaurine fossils belonging to individuals of various sizes, including the holotype of Minqaria, indicate that hadrosaurs were diverse and abundant within the ecosystem.[1] These dinosaurs would have lived in the very latest Cretaceous (Late Maastrichtian) approximately 1 million years before the K-Pg boundary and the Chicxulub asteroid impact that wiped out the dinosaurs.[5]

Palaeobiogeography

[edit]

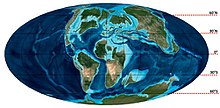

Hadrosaurs, the taxonomic group Minqaria is assigned to, had not been documented from Africa until the discovery of the contemporary Ajnabia; their closest lambeosaurine relatives are all known from Europe. Given this taxonomic position and reconstructions of Late Cretaceous continents and seas, oceanic dispersal between Europe and North Africa is considered the only viable explanation for the presence of hadrosaurs like Minqaria and Ajnabia in Africa. While oceanic dispersal has been considered for the distribution of European hadrosaurs, intermittent land connections as a means of dispersal can not be ruled out. The much more prominent oceanic barrier between Europe and Africa, characterized by deep waters, makes Ajnabia far stronger evidence of this phenomenon, as varying conditions could narrow the gap but not conceivably bridge it entirely. Further evidence for the oceanic dispersal as the model for lambeosaur dispersal also exists from the lack of a complete interchange of fauna between locations, expected from land bridge dispersal. Possible means of dispersal include swimming, drifting, or rafting (wherein animals are transported on top of floating debris or vegetation). Rafting is considered unlikely for a large animal, but it may be possible that young hadrosaurs could be transported this way.[5]

More broadly speaking, the Maastrichtian fauna of the Northern African ecosystem Minqaria inhabited seems biogeographically linked more to Gondwanan faunas—that is, those of the southern continents—than those of Europe and the other Laurasian continents of the Northern Hemisphere. While Laurasia is characterized by tyrannosaurids and herbivorous coelurosaurs, Gondwana is dominated by titanosaurs and abelisaurs, as seen in Morocco. Despite this, a degree of endemism is noted, similar to that of other Gondwanan continents. A small abelisaur from the Sidi Daoui region is unlike those from South America or India, but may be related to North African forms from earlier in the Cretaceous or similarly sized abelisaurs in Europe;[3] likewise, Chenanisaurus may represent a distinct lineage from other known abelisaurs.[2][3] Inversely, other Gondwanan animals from South America such as ankylosaurs, unenlagiines, elasmarians, and megaraptorids are not documented in Africa. This endemism is explained by the fragmentation of the former Gondwanan supercontinent into increasingly distant landmasses, leading to the ancestrally linked faunas of different southern continents becoming distinct. Even within the African continent, the presence of a Trans-Saharan seaway connecting the Tethys Ocean of Europe to the Gulf of Guinea may have isolated the fauna of Northern Africa from more southern portions of the continent, such as fossil-bearing sites in Kenya, and Morocco itself may have been an isolated island.[3]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Longrich, N. R.; Pereda-Suberbiola, X.; Bardet, N.; Jalil, N.-E. (2024). "A new small duckbilled dinosaur (Hadrosauridae: Lambeosaurinae) from Morocco and dinosaur diversity in the late Maastrichtian of North Africa". Scientific Reports. 14 (1). 3665. Bibcode:2024NatSR..14.3665L. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-53447-9. PMC 10864364. PMID 38351204.

- ^ a b Longrich, N.R.; Pereda-Suberbiola, X.; Jalil, N.-E.; Khaldoune, F.; Jourani, E. (2017). "An abelisaurid from the latest Cretaceous (late Maastrichtian) of Morocco, North Africa". Cretaceous Research. 76: 40–52. Bibcode:2017CrRes..76...40L. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2017.03.021.

- ^ a b c d Longrich, Nicholas R.; Isasmendi, Erik; Perada-Suberbiola, Xabier; Jalil, Nour-Eddine (2023). "New fossils of Abelisauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the upper Maastrichtian of Morocco, North Africa". Cretaceous Research. 152: 105677. Bibcode:2023CrRes.15205677L. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105677. S2CID 261090591.

- ^ Perada-Suberbiola, Xabier; Bardet, Nathalie; Iarochène, Mohamed; Bouya, Baâdi; Amaghzaz, Mbarek (2004). "The first record of a sauropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous phosphates of Morocco". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 40 (1–2): 81–88. Bibcode:2004JAfES..40...81P. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2004.07.002.

- ^ a b Longrich, Nicholas R.; Suberbiola, Xabier Pereda; Pyron, R. Alexander; Jalil, Nour-Eddine (2021). "The first duckbill dinosaur (Hadrosauridae: Lambeosaurinae) from Africa and the role of oceanic dispersal in dinosaur biogeography". Cretaceous Research. 120: 104678. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12004678L. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104678. S2CID 228807024.