Minneapolis City Council

Minneapolis City Council | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Leadership | |

President | |

Vice-President | |

| Structure | |

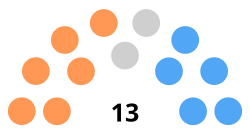

| Seats | 13 |

Political groups | By party

|

| Committees | See Committees |

| Elections | |

| Instant-runoff voting[a] | |

Last election | November 7, 2023 |

Next election | November 4, 2025 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Minneapolis City Hall 350 S Fifth St. Minneapolis, Minnesota 55415 | |

| Website | |

| www | |

The Minneapolis City Council is the legislative branch of the city of Minneapolis in Minnesota, United States. Comprising 13 members, the council holds the authority to create and modify laws, policies, and ordinances that govern the city. Each member represents one of the 13 wards in Minneapolis, elected for a four-year term. The current council structure has been in place since the 1950s.

In recent elections, council membership has been dominated by the Minnesota Democratic–Farmer–Labor Party (DFL). As of 2024, 12 members identified with the DFL, while four identified with Democratic Socialists of America (three members identify as both DFL and DSA). Until the 2021 Minneapolis municipal election, the city's government structure was considered a weak-mayor, strong-council system. However, a strong-mayor charter amendment was passed, and since 2021, the mayor holds executive power and the council has purely legislative duties.

History

[edit]Pre-charter (1850s-1920)

[edit]

The Minneapolis City Council has existed longer than the city's home rule charter. The cities of Minneapolis and Saint Anthony incorporated in 1856 and 1855 respectively, each with councils of their own; in 1872, when the two cities merged, there were twenty aldermen, two representing each of ten council wards.[5] By 1900, the council comprised twenty-six members, two from each of thirteen wards.[6]

In 1896, Minnesota adopted an amendment allowing cities more autonomy, and debates began over how to structure the government and its council.[7] At the time, the city had a council government with a relatively weak mayor role.

The first proposal for an independent charter shifted significant power to the mayor. In 1898, voters rejected that strong-mayor proposal.[6] Five versions tried to organize the city in several ways and failed to reach the approval of the electorate. In 1920, the city adopted the seventh attempt at a home rule charter, establishing the city council we have today.[5][8]

Home rule (1920-1999)

[edit]Over the first thirty years of the charter's existence, there were several failed plans to change the city council's role and makeup. These included proposals to change to the number of representatives or to add at-large seats.[5] In 1929, a proposal to establish a executive mayor and legislative council gained traction after council members were caught up in a stock-market fraud scandal centering Wilbur B. Foshay;[9] it failed to win over sufficient voters to amend the charter.[10] Attempts to give the mayor more authority failed at the ballot box several times in this period, most notably in 1988 when it failed despite the support of mayor Don Fraser.[11] In one of the first successful charter amendments, the city council assumed its current size of 13 single-member wards in 1951.[12] In 1983, the term for representatives was changed from alderman to council member.[5]

The first Black city council member was Van White, elected in 1979 to represent Ward 5.[13] The first openly gay member, Brian Coyle, was elected in 1983 to represent Ward 6 and died of AIDS while in office as council vice president.[14][15]

21st century

[edit]Structure and composition

[edit]The city adopted instant-runoff voting in 2006, first using it in the 2009 elections.[16]

In 2013, Minneapolis elected Abdi Warsame, Alondra Cano, and Blong Yang, the city's first Somali-American, Mexican-American, and Hmong-American city councilpeople, respectively.[16][17][18] In 2017, Phillipe Cunningham from Ward 4 and Andrea Jenkins from Ward 8 were elected to the City Council, becoming the first openly transgender Black man and woman, respectively, to be elected to any office in the United States.[19][20]

In 2021, voters approved a "strong mayor" amendment. This took away the city council's executive authority, delineating the council's role as legislative and the mayor's role as executive.[21]

Major policies

[edit]The city council passed a resolution in March 2015 making fossil fuel divestment city policy.[22] With encouragement from city administration, Minneapolis joined seventeen cities worldwide in the Carbon Neutral Cities Alliance. The city's climate plan is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 15 percent in 2015 "compared to 2006 levels, 30 percent by 2025 and 80 percent by 2050".[23]

In 2018, the city council passed the Minneapolis Comprehensive 2040 Plan and submitted it for Metropolitan Council approval. Watched nationally, the plan rezoned predominantly single-family residential neighborhoods for triplexes to increase affordable housing, seeking to reduce the effects of climate change, and tried to rectify some of the city's racial disparities.[24][25] After the Metropolitan Council approved the plan,[26] in November 2019 the city council voted unanimously to allow duplexes and triplexes citywide.[27] The Brookings Institution called it "a relatively rare example of success for the YIMBY agenda" and "the most wonderful plan of the year."[28]

In 2020, after the murder of George Floyd, nine city council members announced their highly controversial goals to disband the Minneapolis Police Department. Their plan included amending the city's charter to remove the requirement for a minimum number of officers, along with replacing the MPD with a broader public safety agency.[29] The city council was then discovered to have been utilizing private security at a cost of $4,500 per day for three of their members.[30] The plan made it to the ballot in 2021, but ended up failing with only 43% of votes in support of it;[31] along with six of the nine city council members who wanted to disband the police department either voted out or having not ran for reelection.[32]

Controversies and incidents

[edit]In July 2001, DFL council member Brian Herron pleaded guilty to one count of felony extortion. Herron admitted to accepting a $10,000 bribe from business owner Selwin Ortega who faced numerous health and safety inspection violations at his Las Americas grocery stores.[33][34] Herron served a one-year sentence in federal prison.[35]

On November 21, 2002, ten-year DFL council member Joe Biernat was convicted of five federal felony charges, one count of embezzlement, three counts of mail fraud, and one count of making a false statement.[36] Biernat was found not guilty on extortion and conspiracy to extort charges.[37]

In September 2005, Green Party council member Dean Zimmermann was served with a federal search warrant to his home by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The affidavit attached to the warrant revealed that the FBI had Zimmermann on video and audiotape accepting bribes for a zoning change.[38] Zimmermann subsequently lost his re-election campaign, and was convicted in federal court on three counts of accepting cash from a developer and found not guilty of soliciting property from people with business with the city. Zimmermann was released from prison in July 2008.[39]

In 2009, council president Barbara A. Johnson was accused of misusing campaign funds for personal spending. An administrative hearing was held January 26, 2010.[40] The administrative judges at the hearing dismissed six of the eight charges; it upheld two charges—that AAA services were paid for both her and her husband's vehicle and that not all charges for hairstyling or dry cleaning were reasonably related to the campaign. Johnson paid a $200 fine for these violations, the lowest fine possible.[41]

In 2015, DFL council member Alondra Cano used her Twitter account to publish private cellphone numbers and e-mail addresses of critics who wrote about her involvement in a Black Lives Matter rally.[42]

In 2021, while leaving a Pride Day event, a car containing Council Vice President Andrea Jenkins was surrounded by protesters who blocked her from leaving until she signed a list of demands, which included not interfering with the occupied George Floyd Square and the resignation of Mayor Jacob Frey. Jenkins was stuck for over 90 minutes before signing the list so she could go.[43][44]

In July 2022, council member Michael Rainville said during a meeting with his constituents that he was going to go to a mosque in Northeast Minneapolis to "meet with Somali elders and tell them that their children can no longer have [poor] behavior,"[45] in response to incidents on the 4th of July in downtown Minneapolis, during which groups of younger people were seen launching fireworks at buildings and passerby.[46] His comments drew criticism, including from fellow City Council members who attempted to censure him.[47] Jamal Osman, Jeremiah Ellison, and Aisha Chughtai, the City Council's three Muslim members at the time, issued a statement calling Rainville's comments "incorrect," "inappropriate," "disturbing," and "dangerous."[48] Rainville has since apologized for the comments.[49]

At the Minneapolis DFL caucus for Ward 10 on May 13, 2023, supporters of challenger Nasri Warsame rushed the stage when incumbent Aisha Chughtai was scheduled to speak. Chughtai claimed that over a dozen of her supporters and DFL volunteers were physically assaulted in the chaos, while Warsame claimed his campaign manager had been hospitalized due to an injury sustained by a member of the opposing campaign's staff.[50] Later that month, leaders of the DFL voted to permanently bar Warsame from seeking the party's endorsement for any elected office.[51]

Structure

[edit]Electoral system

[edit]In 2006, Minneapolis voters approved the use of the single transferable vote for its municipal elections. The first use of ranked-choice voting was in the 2009 municipal election. However, since the City Council uses single-member districts, the single transferable vote functions the same way as instant-runoff voting.[52] This system of voting is commonly known in the United States as ranked choice voting.

Each member's term is normally four years, and there are no limits on the number of terms a member may serve. In 2020, voters approved a plan to amend the city charter to establish city council elections in 2021 and 2023 for two-year terms instead of the regular four-year terms, with four-year term elections restarting in 2025. The amendment also granted the ability for the city to use this method whenever regular city council elections do not fall in a year ending in a 3 in order to comply with a state law designed to require city council elections in years ending in 2 or 3 after a census.

Wards

[edit]

Each city council member represents one of 13 wards. Ward boundaries are redrawn after each census and approved by the court-appointed Charter Commission.[54] For elections, the 13 wards are subdivided into a total of 137 precincts.[55]

Salary

[edit]Council members have a base salary of $109,846 in 2024.[56] Raises for council members and the mayor are based on "averaging out the increases included in the union contracts they approved the previous year."[57] The rate was $106,101 in 2021. In 2018, all Council Members were paid a base salary of $98,696 annually, plus mileage, free parking, and the usual employee benefits. This salary included an increase of $10,000 approved in late 2017.[58]

Members

[edit]The council is made up of 13 members. The DFL holds 12 seats, while one member (Robin Wonsley) sits as an independent democratic socialist. New members took office January 2024.[59]

Committees

[edit]The Minneapolis City Council operates through several standing committees, each focusing on specific areas of city governance.[60]

Administration & Enterprise Oversight Committee

- Chair: Robin Wonsley (Ward 2)

- Vice-Chair: Linea Palmisano (Ward 13)

- Focus: Oversight of general government, enterprise, and administration operations. Regular evaluation of the City’s Strategic Racial Equity Action Plan and the Mayor’s Office.

Business, Housing & Zoning Committee

- Chair: Jamal Osman (Ward 6)

- Vice-Chair: Jeremiah Ellison (Ward 5)

- Focus: Oversight of community and economic development, housing policy, land-use and zoning policy, and employment and training programs.

Public Health & Safety Committee

- Chair: Jason Chavez (Ward 9)

- Vice-Chair: Robin Wonsley (Ward 2)

- Focus: Oversight of public health and social service programs, civil rights, environmental justice, community safety services, and police reform initiatives.

Climate & Infrastructure Committee

- Chair: Katie Cashman (Ward 7)

- Vice-Chair: Emily Koski (Ward 11)

- Focus: Oversight of community infrastructure, climate resilience, transportation, public works, utilities, and recycling.

Budget Committee

- Chair: Aisha Chughtai (Ward 10)

- Vice-Chair: Emily Koski (Ward 11)

- Focus: Oversight of the city's budget, financial wellbeing, and approval of financial policies.

Committee of the Whole

- Chair: Jason Chavez (Ward 9)

- Vice-Chair: Aurin Chowdhury (Ward 12)

- Focus: Oversight of strategic goals, enterprise-wide initiatives, and Mayor’s Cabinet appointments.

Settlement Agreement & Consent Decree Subcommittee

- Chair: Elliott Payne (Ward 1)

- Vice-Chair: Andrea Jenkins (Ward 8)

- Focus: Oversight of the settlement agreement with the Minnesota Department of Human Rights, coordination on police reform and accountability.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "2023 Endorsements". Twin Cities DSA. 2023-04-27. Retrieved 2023-11-10.

- ^ a b c d e "MplsForTheMany". MplsForTheMany. 2023-07-03. Retrieved 2023-11-10.

- ^ a b c d e f "Our 2023 Minneapolis City Council Voter Guide". All of Mpls. 2023-10-26. Retrieved 2023-11-10.

- ^ "Ranked Choice Voting (RCV)". Minneapolis Elections and Voter Services. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d Casey Carl (April 1, 2019). "Minneapolis Charter and Elected Officials Timelines" (PDF). Legislative Information Management System. City of Minneapolis. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ a b Nathanson, Iric (November 15, 2009). "Struggle over Structure". Minneapolis in the Twentieth-Century (PDF). Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. p. 15-36. ISBN 0873517253. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Minnesota Law Review Editorial Board (1963). "Home Rule and Special Legislation in Minnesota". Minnesota Law Review. 47: 621-641. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ "Charter History". City of Minneapolis. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ Aamodt, Britt (December 10, 2013). "Foshay built utilities empire and Minneapolis' tallest building, but lost it all". MinnPost. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ Nathanson, Iric (November 5, 2009). "One more failed attempt to promote charter change in Minneapolis". MinnPost. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ Nathanson, Iric (November 5, 2021). "Why it only took 120 years for Minneapolis to adopt a 'strong mayor' system". MinnPost. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ Minneapolis, City of (2015-01-01). "Charter History". City of Minneapolis. Retrieved 2024-03-06.

- ^ Boros, Karen (June 13, 2012). "Van White's legacy runs deeper than his historic Minneapolis City Council breakthrough". Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Tevlin, Jon (August 20, 2016). "25 years after Brian Coyle's death, his legacy lives on". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on 2017-07-10. Retrieved 2024-12-04.

- ^ "Brian J. Coyle Papers". Minnesota Historical Society. 1992. Archived from the original on 2018-06-05. Retrieved 2024-12-04.

- ^ a b Regan, Sheila; Coleman, Nick; Nelson, Kathryn G. (November 6, 2013). "Minneapolis Mayoral Election: Betsy Hodges Almost Claims Her Almost Victory; RCV Count Goes Slow". The Uptake. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ Turck, Mary (November 6, 2013). "Election results updated: Hodges in as mayor; Cano, Yang, Palmisano win city council seats; St. Paul counts on Monday". TC Daily Planet. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ Helal, Liala (November 8, 2013). "Voters bring more racial, ethnic diversity to Minneapolis City Council". MPR News. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ Broverman, Neal (2017-11-08). "A Trans Man Has Also Been Elected to the Minneapolis City Council". Advocate. Archived from the original on September 15, 2024. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ Eltagouri, Marwa. "Meet Andrea Jenkins, the first openly transgender black woman elected to public office in the U.S." Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 4, 2018. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ Spewak, Danny (December 3, 2021). "https://www.kare11.com/article/news/local/new-era-in-minneapolis-as-strong-mayor-system-takes-effect/89-e6c7e0d8-c66f-49ac-b2a1-268adbf16ac0". KARE-TV. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

{{cite news}}: External link in|title= - ^ McKenzie, Sarah (March 20, 2015). "City Council passes fossil fuel divestment resolution". Southwest Journal. Minnesota Premier Publications. Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved April 10, 2015.

- ^ McKenzie, Sarah (March 27, 2015). "City joins international alliance committed to curbing greenhouse gas emissions". Southwest Journal. Minnesota Premier Publications. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ "City Council approves Minneapolis 2040 plan". Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder. December 7, 2018. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Grabar, Henry (December 7, 2018). "Minneapolis Confronts Its History of Housing Segregation". Slate Group. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Wan, Elder (September 26, 2019). "Minneapolis' 2040 plan wins Met Council approval". VOXMN. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ Otárola, Miguel (November 8, 2019). "Minneapolis moves forward with allowing triplexes citywide". Star Tribune. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- ^ Schuetz, Jenny (December 12, 2018). "Minneapolis 2040: The most wonderful plan of the year". Brookings Institution. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ Neale, Spencer (26 June 2020). "Minneapolis City Council advances plan to disband police". Washington Examiner. Washington Examiner. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ Lyden, Tom. "Minneapolis Council members get private security after threats". Fox9. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Minneapolis voters reject making consequential changes to the city's police force". Insider. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ "5 MPLS. City Council members ousted as final races are called". Bring Me The News. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-11-09. Retrieved 2019-11-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Demko, Paul (October 10, 2001). "City council member Brian Herron's disgrace left a vacuum in his Minneapolis district". City Pages. Archived from the original on July 15, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ "Feds Indict Minneapolis City Councilman & Union Boss". UNION CORRUPTION UPDATE. National Legal and Policy Center. April 29, 2002. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ^ "Criminal Enforcement Actions 2002". Office of Labor-Management Standards (OLMS). United States Department of Labor. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ Williams, Brandt (November 21, 2002). "Minneapolis councilman convicted on five fraud charges". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- ^ "FBI says it has Zimmermann on tape accepting bribe". KARE. September 10, 2005. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ Brandt, Steve (July 10, 2008). "Back from prison 'sabbatical'". Star Tribune. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ Brandt, Steve (December 21, 2009). "Mpls. council president faces hearing over campaign spending". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on April 11, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ "Warren E. Kaari v. Barbara Johnson" (PDF). Findings of Fact, Conclusions and Order. Office of Administrative Hearings. Retrieved February 14, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Minneapolis City Council Member Alondra Cano under fire for posting phone numbers, e-mail addresses of constituents". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2019-09-17.

- ^ "'It Was Very Violent': Outrage Grows After Video Shows Mpls. City Council VP Andrea Jenkins Being Held By Activists". CBS Local. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "Council Member Andrea Jenkins says protesters held her 'hostage' at Minneapolis Pride event". Bring Me The News. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "Minneapolis councilmember's comments draw contempt: some forgive while others demand action". cbsnews.com. July 9, 2022.

- ^ "Watch: Fireworks fired at people, buildings in downtown Minneapolis". bringmethenews.com. July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Some Minneapolis council members want to censure Rainville, but it's not so easy". startribune.com. July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Pressure mounts against Minneapolis City Council's Rainville". startribune.com. July 12, 2022.

- ^ "Minneapolis councilor's apology for singling out Somali youths over Fourth of July incidents". bringmethenews.com. July 9, 2022.

- ^ Akailvi, Naasir; Wigdahl, Heidi (May 13, 2023). "Minneapolis DFL convention descends into chaos". kare11.com.

- ^ Griswold, David (May 31, 2023). "DFL bans Nasri Warsame from seeking party's endorsement for any office". kare11.com.

- ^ "How the 2009 RCV Election Works". City of Minneapolis. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ Navratil, Liz (2 March 2022). "Minneapolis Charter Commission approves new political boundaries". Star Tribune. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ Navratil, Liz (February 23, 2022). "Minneapolis will soon have new council, Park Board boundaries". Star Tribune. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ "Ward and Precinct Maps". City of Minneapolis. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ Palmisano, Linea; Jenkins, Andrea (2023). "Resolution: Setting the annual salary for Council Members for the 2024-2025 Term" (PDF). City of Minneapolis. Retrieved April 4, 2024.

- ^ Navratil, Liz (21 January 2021). "Minneapolis mayor, some on City Council will donate raises". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Callaghan, Peter. "Minneapolis City Council approved $10,000 raises for new council, mayor". Minnpost.com. Minnpost. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Frasier, Krystal (November 21, 2023). "New Minneapolis city councilor sworn in". KSTP.

- ^ Minneapolis, City of (2024-01-08). "City Council organizes for new term". City of Minneapolis. Retrieved 2024-01-11.