Milton Cline

Milton William Cline (May 16, 1827 in Whitehall, New York – October 7, 1911 in Montrose County, Colorado) was a 19th-century American sailor, soldier, scout and pioneer. His name appears throughout the history of the United States Civil War and post-bellum period.

Early life

[edit]Milton Cline was born in Whitehall, New York to German immigrants, William and Martha Cline on May 16, 1827.[1]

Cline began his career as a sailor aboard the whaling ship SS South Carolina in 1846.[2] He married his wife Elizabeth in 1852. The pair would have three children together.[1]

Military career

[edit]

Prior to the US Civil War, Cline moved to Indiana. During the War, he served as a scout with the 3rd Regiment Indiana Cavalry. Under the command of Major General Joseph Hooker and Major General George Henry Sharpe[3] Cline was assigned to a newly formed core of scouts. He later rose to chief scout.[citation needed] In one mission, Sgt. Cline managed to attach himself to a Confederate cavalry captain and rode the entire length of Lee's lines a few days before the Battle of Chancellorsville.[4] Sharpe requested that Federal military authorities send him tens of thousands of dollars in captured Confederate currency, for him to give to his military scouts and civilian spies to use.[5][6]

Cline's success as a spy was mixed. According to one account, he accomplished "the deepest and longest infiltration of the Confederate Army recorded during the war"[6] and was instrumental in obtaining key intelligence about orders being sent by Jefferson Davis.[7] However, he was later blamed for the failure of an infiltration mission, the Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid during the Battle of Walkerton, leading to the infamous Dahlgren affair. The botched raid caused all but one of the infiltrators to be killed or captured.[6] Colonel Ulric Dahlgren was killed in retreat, and the later desecration of his corpse by the Confederates caused great offence across the north.[8][more detail needed]

Cline and the rest of the 3rd Indiana Cavalry were mustered out of the Union Civil War ranks in August 1864.[9][10][11][12] Cline would later be known as "Captain", yet no information remains how he became known by this title.[4]

Colorado pioneer

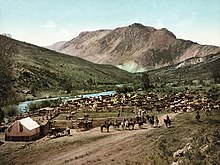

[edit]After the Civil War, Cline moved west. Historical records list Cline as one of the first prospectors and founding settlers of the county and town seat of Ouray, Colorado. By 1875, Cline had travelled from Silverton to explore the area that would come to be known as Ouray.[4][13]

Founding of Ouray

[edit]Ouray was incorporated by Cline and Judge R.F. Long in August 1876. Cline served as President of the Board of Trustees for the county's incorporation, and paid for some of the incorporation expenses.[14][15]

At the time, the terrain around Ouray was treacherous and difficult to reach. Positioned at the north end of the San Juan mountains, sheer cliff faces prevented easy access. It would be years before Otto Mears would build the "impossible road" linking Ouray to Silverton.[16] Later parts of the route would become known as the Million Dollar Highway.

By November 1876, Ouray had 400 inhabitants.[17] "Captain" Milton W. Cline is listed as Ouray's first postmaster,[18][19] treasurer,[20] Justice of the Peace,[21] mayor and Sheriff of Cimarron.[22][citation needed] Shortly after being appointed county treasurer, in March of that year, he resigned the role of treasurer.[23] In 1877, he was named to the board of the first Bank of Ouray.[24]

Business endeavors

[edit]Alongside Frederick Walker Pitkin, Cline founded the Michael "Mickey" Breen mine on Engineer Pass.[1] After several years of prospecting and owning mines such as "The Mickey Breen" and "Mother Cline Slide", Cline became a cattle rancher.[19] Between 1876 and 1879, Capt. Cline and his family settled in Cimarron, Colorado.[25] At its peak, Cline's ranch covered 450 acres (180 ha) and had 5,400 head of cattle.[26]

Cline's ranch in Cimarron was a regular stopping off point for travelers and he was additionally engaged as a road overseer.[27] His ranch was described as a "headquarters for strangers", where "no one goes away hungry".[28] There, he managed a stage coach station where passengers rested overnight, an enterprise that was said to make him "lots of money".[29] Cline's wife Elizabeth, known as "Mother"[30] to visitors, was esteemed for her hospitality to ranch visitors and those passing through the area.[31]

Involvement with the Ute people

[edit]

Cline had a close relationship with Chief Ouray and the Ute people who neighbored his range. He was known to intervene in local disputes between the Tabeguache and the white settlers,[32] and his ranch became a meeting spot to resolve conflicts.[33] Governor Pitkin claimed Cline had more influence when negotiating with the Ute than any other white man in Colorado.[34]

Meeker Massacre

[edit]During the hostage crisis following the Meeker Massacre, Cline was among the party sent by the US government to negotiate the release of hostages taken by the Utes.[35][36] Cline personally drove the wagon that carried Chief Ouray and his wife Chipeta to negotiate the release of women settlers that had been taken hostage.[37] After negotiations for their freedom were secured, Cline drove the party to safety.[38]

Blue Mountain Incident

[edit]In 1880, Cline was imprisoned after becoming involved in an incident between Ute tribe members and a travelling freight wagon crew.

On September 29, 1880 several Ute tribe members went into a freight wagon's camp on nearby Blue Mountain Mesa asking for food. They were refused by the travelling party.[39] As the tribe members departed, one of the freighters, A Donald Jackson shot and killed one of the inquiring tribe members, Johnson Shavano. The murder victim happened to be the son of the Ute Chief Shavano.[40]

After the shooting, the freighters quickly moved their camp to Cline's ranch for safety, as some military troops were camping there.[41] Upon learning of the shooting, 60 Utes assembled by Shavano, headed to Cline's ranch to avenge Johnson Shavano's death. On his ranch, Cline found several bands of angry Ute warriors potentially coming in contact with the 500 assembled infantry and 3-400 assembled calvary troops camping there, as well as the group of freighters who perpetuated the incident.[42] Sensing the situation could quickly get out of control if the military became involved, Cline, in an effort to reduce tension, sought to appeal to the Utes by suggesting to take perpetrator A.D. Jackson to Gunnison to stand trial for Johnson's murder.

Cline assured the military that he could escort Jackson to Gunnison safely without retribution. Cline and three military escorts set off with Jackson the next morning. Three miles outside Cline's ranch, Jackson was taken hostage, said to be tortured and subsequently killed by the vigilantes. Cline was considered responsible for turning Jackson over to the Utes for retribution.[43] Cline was arrested for complicity in Jackson's murder[44] and placed in Gunnison jail.[45][46] Due to the allegations of torture, and the ongoing challenges settlers were having with the Ute people, Cline was vilified in the press for his alleged involvement in the crime, and significant funds were raised to support his conviction.[47] While Cline was in prison, rumors circulated in the county that a band of Ute warriors was making plans to spring him from jail.[48]

At his trial, Cline was described as well-educated, and "intelligent in his conversation". Taking the stand in his defense, Cline was "convincing" at showing that he was a victim of circumstance, rather than a perpetrator.[49] Cline was eventually cleared of all wrongdoing.[50] Later, Jackson's body was found and did not show evidence of torture.[51]

The next year, a Grand Jury indicted a number of Ute warriors for Jackson's death. Cline was named accessory to murder, causing him great anguish.[52][53] The case never went to trial.

Later life

[edit]After the events at Blue Mountain and Cline's acquittal, Cline did not find himself short of controversy. In 1881, a man died on his ranch in pursuit of medical treatment, and Cline was publicly accused of stealing from the body.[54] The accusation suggested Cline had regularly stole from the Utes, wagon trains and stagecoaches that crossed his land, but that "robbing from the dead is carrying larceny beyond frontier limits", even for Cline.[54]

In May 1882, Cline's wife Elizabeth died of cancer.[31] After her death, less is known about Cline's later life. He was known to be employed in carpentry for other Colorado settlers in 1899.[55] That year, he was "chief contractor, builder and decorator" of "one of the neatest and prettiest schoolhouses in the county".[56] In 1904, Miltion Cline was granted a pension from Washington for his Civil War service.[57] After a short illness, Cline died on October 7, 1911, in Montrose County, Colorado. He was 86 years old. At the time, the Ouray County Plaindealer noted his death as "A famous old pioneer dead."

Legacy

[edit]Some of the land that once made up Cline's Cimarron ranch is today is part of the Curecanti National Recreation Area. The historic town of Cimarron no longer exists, but parts are preserved as "Historic Cimarron" within the recreation area. The National Park Service maintains a visitor center, campground and picnic area on the site.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Cox, Marilyn (2019-01-15). "Who was Captain Cline?". Montrose Daily Press. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Crewlist for the voyage aboard the South Carolina". Whaling Project. City of New Bedford [Massachusetts] Free Public Library. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ^ Book by Peter G Tsouras "Major General George H. Sharp" and the Creation of American Military Intelligence. Book 2 Peter G Tsouras: Scouting for Grand and Meade, Book 3: Edwin C. Fishel, The Seacret War For The Union

- ^ a b c Silbernagel, Bob (2024-09-12). "Civil war spy aided hostages after Meeker tragedy in 1879". The Grand Junction Daily Sentinel. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Lincoln's BMI or Union Spymaster". 18 April 2019.

- ^ a b c "NCOs: The MI Tradition" (PDF). p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

- ^ Miller, John A. "Zora: The Pivotal Crossroad of the Civil War". The Civil War Along Tom's Creek and Waynesboro Pike. Emmitsburg Area Historical Society.

- ^ DeMarco, Michael. "Elizabeth L. Van Lew (1818–1900)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ Book by Peter G Tsouras: Scouting for Grand and Meade, Book by Edwin C. Fishel, The Seacret War For The Union

- ^ "TSOURAS: Major General George H. Sharpe and the Creation of American Military Intelligence in the Civil War (2018) | Book Reviews | Civil War Monitor". www.civilwarmonitor.com. Retrieved 2021-03-13.

- ^ Fishel, Edwin C. (1996). The Secret War for the Union: The Untold Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-395-90136-6.

- ^ Tsouras, Peter G. (2014-04-29). Scouting for Grant and Meade: The Reminiscences of Judson Knight, Chief of Scouts, Army of the Potomac. Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1-62914-041-4.

- ^ Cox, Marilyn (2008-06-25). "The Captain and Mother Cline". Montrose Daily Press. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Ouray Times July 21, 1877 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Ouray Times July 21, 1877 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Impossible Road: Photos of the Otto Mears Toll Road". Western Mining History. Retrieved 2024-09-14.

- ^ O'Rourke, Paul M. (1980). Frontier in Transition A History of Southwestern Colorado (PDF). Bureau of Land Management Colorado Cultural Resources.

- ^ "Ouray Times August 4, 1877 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ a b "Ouray Times September 1, 1877 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Silver World February 10, 1877 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Gunnison Daily News-Democrat April 1, 1882 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ Gunnison Daily Review Press notes that an election that was held to choose Cimarron's town officers declared Captain Cline "chosen marshal and appointed deputy sheriff." 22

- ^ "The Plaindealer (Ouray) May 19, 1911 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Rocky Mountain News (Daily) November 27, 1877 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ a b Gunnison, Mailing Address: 102 Elk Creek; emergency, CO 81230 Phone: 970 641-2337 x205 This phone is not monitored when the building is closed If you are having an; Us, call 911 Contact. "Historic Cimarron - Curecanti National Recreation Area (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Historic Cimarron". National Park Service. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ "Montrose Daily Press October 7, 1911 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The San Juan Prospector July 29, 1876 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Gunnison Daily News-Democrat October 12, 1881 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Solid Muldoon (Weekly) December 26, 1879 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ a b "Silver World May 6, 1882 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The San Juan Prospector January 3, 1880 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Rocky Mountain News (Daily) December 31, 1879 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Colorado Weekly Chieftain October 16, 1879 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Meeker Massacre and the Battle of Milk Creek". Rio Blanco County Historical Society. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ "Rescued: The White River Captives Released" (PDF). The Ouray Times. 25 October 1879.

- ^ "Montrose Daily Press October 7, 1911 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Silver World November 1, 1879 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Leadville Weekly Democrat October 16, 1880 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Weekly Register-Call October 8, 1880 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Leadville Weekly Democrat October 16, 1880 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Gunnison Review (Weekly) October 16, 1880 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The San Juan Prospector October 23, 1880 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Gunnison News October 30, 1880 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Rocky Mountain News (Daily) November 7, 1880 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Gunnison Review (Weekly) October 30, 1880 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Weekly Register-Call June 9, 1882 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Rocky Mountain News (Daily) October 29, 1880 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Gunnison Democrat October 27, 1880 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ Simmons, Virginia McConnell (2011-05-18). Ute Indians of Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-1-4571-0989-8.

- ^ "Silver World December 18, 1880 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Fort Collins Courier May 12, 1881 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Silver World June 11, 1881 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ a b "The Solid Muldoon (Weekly) October 21, 1881 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Montrose Enterprise July 22, 1899 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Montrose Press December 22, 1899 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "The Rocky Mountain News (Daily) September 17, 1904 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- People of Indiana in the American Civil War

- 1911 deaths

- People from Whitehall, New York

- People from Montrose County, Colorado

- 1827 births

- Military personnel from Indiana

- American prospectors

- Colorado pioneers

- Curecanti National Recreation Area

- American ranchers

- Colorado postmasters

- People from Ouray County, Colorado

- People from Gunnison County, Colorado

- American Civil War spies