Mehtab Bagh

| Mehtab Bagh | |

|---|---|

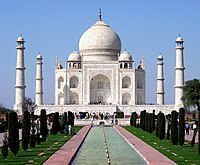

View towards the Taj Mahal from Mehtab Bagh | |

Location of Mehtab Bagh | |

| Type | Garden |

| Location | Agra, Uttar Pradesh |

| Coordinates | 27°10′47″N 78°02′31″E / 27.17972°N 78.04194°E |

| Area | 25 acres (10 ha) |

| Created | 1652 |

| Operated by | ASI |

| Open | Year round |

| Status | Open |

Mehtab Bagh (lit. 'Moonlight Garden') is a charbagh complex in Agra, North India. It lies north of the Taj Mahal complex and the Agra Fort on the opposite side of the Yamuna River, in the flood plains.[1][2] The garden complex, square in shape, measures about 300 by 300 metres (980 ft × 980 ft) and is perfectly aligned with the Taj Mahal on the opposite bank.[3][4] During the rainy season, the ground becomes partially flooded.[5]

History

[edit]

The Mehtab Bagh garden was the last of eleven Mughal-built gardens along the Yamuna opposite the Taj Mahal and the Agra Fort.[2] The garden was built by Emperor Babur (d. 1530).[6] It is also noted that Emperor Shah Jahan had identified a site from the crescent-shaped, grass-covered floodplain across the Yamuna River as an ideal location for viewing the Taj Mahal. It was then created as "a moonlit pleasure garden called Mehtab Bagh." White plaster walkways, airy pavilions, pools and fountains were also created as part of the garden, with fruit trees and narcissus.[7] The garden was designed as an integral part of the Taj Mahal complex in the riverfront terrace pattern. Its width was identical to that of the rest of the Taj Mahal.[2] Legends attributed to the travelogue of the 17th century French traveler Jean Baptiste Tavernier mention Shah Jahan's wish to build a Black Taj Mahal for himself, as a twin to the Taj Mahal; however, this could not be achieved as he was imprisoned by his son Aurangzeb. This myth had been further fueled in 1871 by a British archaeologist, A. C. L. Carlleyle, who, while discovering the remnants of an old pond at the site had mistaken it for the foundation of the fabled structure.[2] Thus, Carlleyle became the first researcher to notice structural remains at the site, albeit blackened by moss and lichen.[5] Mehtab Bagh was later owned by Raja Man Singh Kacchawa of Amber, who also owned the land around the Taj Mahal.[8]

Frequent floods and villagers extracting building materials nearly ruined the garden. Remaining structures within the garden were in a ruinous state. By the 1990s, the garden's existence was almost forgotten and it had degraded to little more than an enormous mound of sand, covered with wild vegetation and alluvial silt.[5][9]

Site plan

[edit]

Inscriptions on the site of Mehtab Bagh mention that it adjoins other gardens to the west; these are called "Chahar Bagh Padshahi" and "Second Chahar Bagh Padshahi".[10] A compound wall surrounded the garden; it was made of brick, lime plaster, and red sandstone cladding. Measuring about 289 metres (948 ft) in length, the river wall is partially intact. Built on platforms, there were domed towers of red sandstone in an octagonal shape, which may have stood at the corners. A 2–2.5 metres (6 ft 7 in – 8 ft 2 in) wide pathway made of brick edged the western boundary of the grounds, covering the remains of the boundary wall to the west.[5] Near the entrance is a small Dalit shrine on the riverside.[11] Of the four sandstone towers, which marked the corners of the garden, only the one on the southeast remains. A large octagonal pond on the southern periphery reflects the image of the Mausoleum.[2] There is a small central tank on the eastern side. Water channels enrich the landscape and there are baradaris on the east and west. There is a gate at the northern wall.[2][4] The foundations of two structures remain immediately north and south of the large pond, which were probably garden pavilions. From the northern structure a stepped waterfall would have fed the pool. The garden to the north has the typical square, cross-axial plan with a square pool in its centre. To the west, an aqueduct fed the garden.[12] Other structures which are not in keeping with the original landscape plan include nurseries owned by private individuals, a temple in place of a gazebo, a statue of B. R. Ambedkar holding the Constitution of India in the courtyard, and relics of a water supply network to the park.[2]

Restoration

[edit]Restoration of the Mehtab Bagh began after the ASI survey, setting new standards for Mughal garden research. This included a surface survey, historical documentation, paleobotanical assessment, archaeological excavation techniques, and requirements coordination with the Ministries of Culture, Tourism, and Planning.[13] Restoration began in the 1990s, aided by the Americans, during which barbed-wire fencing was added to the Mehtab Bagh site.[14] The garden's original ambiance was restored as ASI insisted on having plants that the Mughals had used in their gardens. Though the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI) had suggested planting of 25 pollution-mitigating plant species every 2 metres (6 ft 7 in)[2] in the proposed renovation of the garden, this was opposed by the ASI. The Supreme Court intervened in the matter in favour of ASI who wanted the garden to only have plants that the Mughals used in their gardens.

A common list of plants was suggested. ASI landscape artists meticulously planned the replanting of trees, plants and herbage to match the original Mughal gardens, replicating the riverside gardens brought to India from Central Asia in Shalimar Bagh in Kashmir. Some 81 plants adopted in Mughal horticulture were planted, including guava, maulshri, Nerium, hibiscus, citrus fruit plants, neem, bauhinia, ashoka and jamun. The herbage was planted in such a way that tall trees follow the short ones, then shrubs, and lastly flowering plants. Some of these plants produce bright-coloured flowers that shine in the moonlight. The park has been reconstructed to its original grandeur and has now become a very good location to view the Taj Mahal. The Mehtab Bagh also supports an ecological zones attracting residential and migratory birds. [3][2][6]

Archaeology

[edit]Archaeological excavations in the Mehtab Bagh site have been described as "setting new archaeological standards for Mughal garden research", using paleobotanical and excavations techniques.[13] Excavations to the extent of 90,000 cubic metres of earth, were carried out by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), in 1994. The excavations unearthed a large octagonal tank with 25 fountains, and a garden, divided into four compartments. Mumtaz Mahal's tomb was found to be situated halfway between the Taj Mahal complex's main entrance and the ends of the Mehtab Bagh site.[2] This is corroborated by a letter from Aurangzeb addressed to Shah Jahan in which he referred to the condition of the garden after the flood event in 1652 AD.

Black Taj Mahal

[edit]The Black Taj Mahal is a legendary black marble mausoleum that is said to have been planned to be built across the Yamuna River opposite the Taj Mahal. Mughal emperor Shah Jahan is said to have desired a mausoleum for himself exactly to that of the one he had built in memory of his second wife, Mumtaz Mahal, but built entirely out of black marble. [15][unreliable source?]. But Shah Jahan was not able to complete it as he was put under house arrest by his son Aurangzeb in the Agra Fort. Shah Jahan died in 1666 and his son, Aurangzeb planned to bury his father's body in the Taj Mahal next to Shah Jahan's wife, Mumtaz Mahal. The site for the Black Taj Mahal was converted into the Mehtab Bagh.

References

[edit]- ^ "Ticketed Monuments, Uttar Pradesh, Mehtab Bagh". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Avijit, Anshul (7 August 2000). "Nursery of History: The ASI's efforts to restore the Taj Mahal's fabulous medieval garden are bearing fruit". India Today Weekly Magazine. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ a b Datta, Rangan (5 July 2024). "Agra beyond the Taj: Exploring tombs and gardens on the left bank of Yamuna". The Telegraph. My Kolkata. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Places of Interest". Mehtab Bagh. Official website of the Government of Uttar Pradesh, Department of Tourism. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d "ANNEXURE Il GARDENS A. Mahtab Bagh A Development Plan". Archaeological Survey of India. 1996. pp. 16, 17, 23. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ a b "Mehtab Bagh". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Stuart, David (1 September 2004). Classic Garden Plans. Frances Lincoln Ltd. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7112-2386-8. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Grewal, Royina (1 January 2008). In the Shadow of the Taj: A Portrait of Agra. Penguin Books India. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-14-310265-6. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Singh, Sarina (1 September 2009). India. Lonely Planet. p. 409. ISBN 978-1-74179-151-8. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Muqarnas. BRILL. 1997. p. 160. ISBN 978-90-04-10872-1. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Thomas, Gavin (1 October 2010). The Rough Guide to Rajasthan, Delhi & Agra. Rough Guides Limited. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-84836-555-1. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Leoshko, Janice (2002). "Book review - The Moonlight Garden: New Discoveries at the Taj Mahal". Persimmon - Asian Literature, Arts and Culture. p. 1. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ a b Conan, Michel (1999). Perspectives on Garden Histories. Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 124–. ISBN 978-0-88402-269-5. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ^ Agrawal, S. P. (1 January 1999). Information India: 1996-97: Global View. Concept Publishing Company. p. 161. ISBN 978-81-7022-786-1. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Black Taj Mahal Myth". Retrieved 11 June 2013.