Meduna

Meduna family timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||

1000 — – 1100 — – 1200 — – 1300 — – 1400 — – 1500 — – 1600 — – 1700 — – 1800 — – 1900 — | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

darker shades: historically recorded persons | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Meduna is a toponymic surname of Celtic origin derived from the hydronym Meduna via the related toponym Meduna (di Livenza).[1][2] It is first attested as the name of the homonymus river in a charter issued by Charlemagne in the year 794,[3] and appears as a surname in the early 11th century in Italy and since the late 16th century in the Czech lands, form where it spread mainly to Austria, the United States and Brazil.[4][5][6]

Geographic distribution

[edit]As of 2014, 47% of all known bearers of the surname Meduna lived in Europe and 29% in the United States. The surname is most common in the Czech Republic, where it is held by 620 people (frequency 1:17,151). It is still predominant at the location of its 16th century origin in Chrudim (111 or 1:1,344) and Pardubice (57 or 1:3,369) districts. 13% live in the South Moravian Region, a key settlement area during the Habsburg Empire en route to today's territory of Austria. The surname reached Brazil from Europe mainly in the 19th and 20th centuries, where it has 167 occurrences.[6][7][8]

Notable people

[edit]Notable people with the surname include:

- Bartolomeo Meduna, Conventual Franciscan scholar and author

- Melissaeus (Meduna) family of Utraquist Hussite Bohemian priests

- Giovanni Battista and Tommaso Meduna, Italian architect and engineer brothers

- Johann Meduna von Riedburg, ennobled officer in the Austro-Hungarian Army

- Bertha von Meduna, Baroness and Chamber Woman of Archduchess Sophie of Austria

- József Meduna di Montecucco, award-winning Italian-Hungarian salami maker

- Ladislas J. Meduna, Hungarian psychiatrist and neuropathologist

- Johann Meduna, Austrian resistance fighter against the Nazi regime

- Veronika Meduna, New Zealand biologist, science journalist and writer

- Alexander Meduna, theoretical computer scientist and expert on compiler design

- Michal Meduna, Czech footballer

- Mathew Paul Meduna, ISEF awardee in 2003

Name and origin

[edit]Etymology

[edit]Various similar and related etymological proposals exist for the origin of the name, yet all agree on its Celtic foundations.

The second element -dun has been recognized as a continuation of the Celtic *dhūno- ('oppidum, fortified hill, castle'), in use among the Carni Gauls that penetrated and populated the region of current Veneto and Friuli between the 4th and 2nd centuries BC, possibly as part of the great Celtic migration towards Pannonia and the Balkan regions. The variety of Celtic toponyms and hydronyms in the Pre-Alps suggests that the culture may have resisted in the region from the 4th century BC until complete Latinisation during the imperial era. Some of these assumed Celtic or Celticised oppida in the region have been proposed as locations of subsequent castles in the Middle Ages, including the Castello di Meduno.[1][9][10]

For the first element of the name, it has been proposed that it may be derived from either a Gaulish *mago ('great'), combnined into *Magodunum ('great/big fort'), or an Indo-European *medhu ('middle'), resulting in a Celto-Latin *Mediodunum ('in the middle of fortified heights'). Other scholars have suggested a compound *Mago-dunum ('fort on the plain') based on mago ('field'), as well as a Celto-Latin Medio-dunum ('that which stands or flows in the midst' of the hills/mountains) – the latter with clear reference to the river. Such an etymological origin is also found, for example, in the historical Meduana flumen, the current Mayenne river in France, with a derivative morpheme.[11][12][13] The hydronym of the French Mayenne river also produced the de Mayenne family name – in some sources also attested as de Meduana and de Meduno – which is, however, unrelated to the Meduna/Meduno surnames of Italian origin, beyond the shared Celtic etymological root.[14]

The hypothesis and interpretation of the river Meduna being "in between mountains" is based on the fact that the torrent has its source in the Carnic Pre-Alps and generates two related town names along its course: Meduno,[15][16] at its downstream outlet in the high plain, and Meduna as it flows into the Livenza river. On the upper course of the stream, there are also three villages called Tramonti (Tramonti di Sopra, Tramonti di Mezzo, Tramonti di Sotto), which would constitute a direct and proper translation of the Celtic counterpart, transmitted through Latin and Friulian (attested as Tramonz in 1182) into Italian, thus making it a linguistic synonym of the word Meduna/Meduno.[10] However, this proposal has been contested since the second part of the hydronym/toponym Meduna/Meduno (-dun) does not have a generic meaning of "mountains" and the Latin appelative mons/montes has not inherited a second semantic value of "castle/castles" in Romance dialects.[1]

A different etymological approach is based on the frequent hydronymic and oronymic transposition of theonyms in the Celtic cultural environment, thus assigning rivers and geographical features names of deities.[1] An inscription from the Rhineland contains a dedication to the goddess Meduna, venerated by the local Celtic tribe of the Treveri. The small consecration altar (from Roman times) found in Bad Bertrich near a hot spring associates the goddess with the source of water.[17][18] Another town in the vicinity of nearby Trier, Mettendorf (according to other sources nearby Möhn), traces its name back to the locality of Villa Medona recorded in the year 768.[19][20][21] In Insular Celtic mythology, there is mention of a goddess Medb or Maeve (in Ireland) and Mèadh (in Wales) – based on which a Celtic theonym *Medwa (as warrior goddess) has been proposed as a basis for *Medw-una, therefore dedicating the Friulan river to a Celtic deity.[1]

While linguistic traits were shared across the ancient Celtic tribes, a cult of any of these particular deities among the Gallic tribes of the eastern Alps has not been attested. Finally, other sources propose that the name can be derived from an ancient proper name Metonius or another Celtic divinity attested in insular Britain, Matun(i)us.[22][23][24][25]

Localities of similar names of distinct origins include the settlement of Medun in Montenegro, the village of Medana in Slovenia, or the town of Modugno in Apulia, first mentioned as “de loco Medunio” in 1021 and deriving its toponym from the Latin Medunium ('in the middle' of Bitonto and Bari).[26]

Earliest attestations

[edit]In the year 794, twenty years after Charlemagne defeated Desiderius, the last king of the Lombards, and established the March of Friuli under Frankish dominance, we find the rivers Meduna and Livenza documented for the first time in a charter issued by Charlemagne (“et post hunc fluvium Medunae et aqua Medunae defluit in Liquentiam”) – six years before his coronation as Emperor of the Romans.[3]

Ten years later, in 804, a charter settling property ownership between two clerics attests the locality of Matunianus, which is believed to be today's town of Meduna di Livenza. The charter is stored in the Archivio di Stato in Verona (Ospedale Civico, roll 5[A][27]).[28][29][30]

The hydronym Meduna proper is further attested in the year 996 in a charter issued by Holy Roman Emperor Otto III – again, as the confluence of the Meduna and Livenza rivers (“et aqua Meduna fluit in Liquencia”).[3]

Meduna and Meduno

[edit]The hydronym Meduna (La Midùna in Friulian) is grammatically feminine, which is a common trait of large rivers in both Friulian popular tradition as well as rustic dialects of Treviso and Belluno.[31] In contrast, the town name of Meduno (Midun in Friulian) is grammatically masculine. It remains impossible to ascertain the temporal precedence of the two names.[1] Some authors, however, suggest that the masculine name was originally applied to the entire area wedged between the mountains (Val Tramontina and Val Meduna), subsequently passed to the torrent and made feminine (as in numerous Friulian and Venetian cases) and only in more recent (post-Roman) times applied as a carryover toponym to the castle and town of Meduna – thus giving rise to Meduna as a surname from the 11th century onwards.[10] The separate noble family of Meduno, similarly, is attested since the early 12th century until their extinction in 1514.

Italian and Latin historical records of the 10th to 17th centuries show a range of variations in notation of both names. Meduno appears as Medun, Medunium, Methun, Metuno, Metunium, Mituno,[32] Midun, Midunum, and Midhuna [sic!].[33] Similarly, the name Meduna can often be found in records as Metuna (mostly in Latin), Methuna, or Mettuna, Miduna.

Patriarchate of Aquileia

[edit]The recorded history of the Meduna family begins with the advent of the High Middle Ages in the territory of the March of Treviso.

Castello di Meduna

[edit]The castle of Meduna was built around the year 1000 on the initiative of the Patriarchs of Aquileia, probably on the foundations of a fortress that was several centuries older.[34][35] The castle is considered as part of fortifications erected in response to the Hungarian raids of the preceding decades. When the castle was built, a branch of the Meduna river, after having collected the waters of the Fiume and the Sile, ran into the bed of the Sambellino. In this way the castle of Meduna was located between two large rivers: the Meduna and the Livenza.[5]

The current palazzo del governo of “La Meduna” (or simply "Meduna", as the town was called until 1 September 1884, when the denomination “di Livenza” was formally adopted by royal decree n. 2578) is a fusion of what remains of the ancient castle with the palace of the Venetian Patricians Michiel dalla Meduna, built towards the end of the 16th century.[35][36][37] Bartolomeo Meduna is also mentioned as "reconstructor" of the castle.[38] The remains of the medieval castle are located on the south-east side, distinguished by the sawtooth cornice under the roof and by a series of windows with a Romanesque arch from the era.[5]

Meduna was a fief of the Patriarchs of Aquileia who gave it as investiture to the Lords of Meduna and then to feudal lords. In 1204, the Municipality of Meduna entered the Parliament of Udine.[4] The first document that explicitly mentions the castle of Meduna dates back to 1223.[39] Other documents of the same year mention the Patriarch's house in Meduna and the church. The jurisdiction of Meduna (Methuna) in the thirteenth century included, among other, a locality listed as “Methuna la villa”.[4][5]

Being a residential fiefdom and a gastaldia, the castle at Meduna was the seat of the feudal government, the residence of the feudal lord, it depended directly on the Patriarch and was administered by a patriarchal official called a gastaldo.[5]

Meduna ancestral lineage

[edit]Shortly after the year 1000, the first noble family that was invested by the Patriarch of Aquileia with the fief settled in the castle. In accordance with the custom of the time, the family took its name from the land / the castle itself and was henceforth called “di Meduna”.[4][5] The family, which belonged to the class of noble feudal lords of the church of Aquileia, was represented in the Friulian Parliament. Medieval chronicles sporadically mention members of the family since their adoption of the name.[35][40][41]

The investiture of the fief continued to be renewed over the next centuries. Patriarch Bertoldo, as his predecessors, had granted the castle as a fief of residence to the homonymous family. Only when Gena di Meduna died without direct heirs, on 29 May 1289 the Patriarch Raimondo della Torre invested his relatives, the two brothers Emberaldo and Gabrio della Torre, with the fief.[34][42]

Other branches of the family continued, and by the 14th century the Meduna family were the castellans once again. In 1326 the Meduna nobles made an agreement with the lords of Panigai and tried to sell the castle to the lord of the Treviso area, Rizzardo da Camino – who already owned Motta and had particular aims on Meduna throughout his life. However, the conspiracy was discovered and, guilty of felony, the conspirators (Floramonte, Lavinio, Varnero and Nicolò di Meduna) were banished by the Patriarch in 1327.[40][43][44][45][46][34][47][48][49][50]

In a violent act of vendetta,[47] the banished Meduna nobles, supported by the Caminesi, attacked the town of Meduna itself, causing considerable damage. The riots also affected neighbouring villages. The Meduna were later pardoned by the Patriarch but were no longer granted their ancient fiefdom.[35][51][46][52][53][54]

Historical mentions

[edit]In different historical sources the prepositions in front of the name – di, da, della, de la, and de (in Latin versions) – were often used interchangeably in relation to the same person. Titles such as D. (Don, Dominus) or Nob. (Nobile, Noble) mentioned in chronicles are omitted in the below lists (chronological, unless preceded by lineal descent).

The following is a list of members of the Meduna family mentioned in historical records (until the end of the Patriarchate of Aquilea in 1420):

| Year | Name | Alternative spelling | Details | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1190 | Henricus Vice Dominus de Meduna | [55][39] | ||

| 1219-1223 | Varnerio di Meduna | Varnero, Warnerio, Warniero, Wernero | [35][34][56][57] | |

| Osalio di Meduna | [35] | |||

| 1223 | Odolricus de Meduna | faber (smith, architect) | [58] | |

| Seraphinus de Meduna | son of Odolricus | |||

| Barnabas de Meduna | ||||

| Bosellus de Meduna | presbyter | |||

| 1246 | Tosco della Meduna | |||

| 1248 | Folchomarius de Meduna | Folcomarius, Falcomario della Meduna | [59][57][60] | |

| Pergulinus de Meduna | [61] | |||

| 1274-1284 | Ramillus de Meduna | Ramillo, Ramello, Ramellus, Ramuello di Meduna | son of Pergulinus, feudal lord of the Church of Aquileia, 'ministeriale patriarcale di Meduna', had a fief of five and a half manors in Meduna | [62][34][63][61][42] |

| 1274 | Isnardus de Meduna | [61] | ||

| Jacobus Tempesta de Meduna | son of the late Isnardus, had a feudal manor in Basedo, Chions | |||

| 1278 | Marinus de Meduna | Mariano di Meduna | feudal lord of Meduna | [34][64] |

| 1289 | Gena di Meduna | invested with the fief of Meduna, died without heirs | [34][42] | |

| 1292 | Bosello di Meduna | granted a residential fief in Cividale on 6 March 1292 | [65] | |

| c. 1292 | Valentinus de Meduna | Valens | [61][66][58] | |

| Folchomarius de Meduna | Falcomario | |||

| 1295 | Artichus de Meduna | [61] | ||

| Johannes Thomasius de Meduna | son of the late Artichus, had a fief of two and a half manors in Meduna | |||

| 1295-1330 | Morandus di Meduna | Morando | 'gastaldio Medunae', married to Galliana di Pinzano, had a fief of manors in and around Meduna | [67][44][34][61] |

| 1296-1335 | Floriamontus di Meduna | Floramonte, Florimonte, Floramando, Florianus, Floriano | imperial notary, banished by the Patriarch of Aquileia in 1327 (along with Lavinio, Varnero, and Nicolaus) after their rebellion | [43][44][45][46][34][47][68][69][70] |

| 1335-1343 | Anthonius de Meduna | Antonius, Antonio, della Meduna | notary, son of Floriamontus | [65][71][72] |

| c. 1300 | Meynardus de Meduna | Meynhardo | [61] | |

| Insindricus de Meduna | ||||

| 1295-1325 | Martinus de Meduna | Martino, Mastinus, Mastino de Miduna | brothers, had a fief of eight manors in Azzano [and more in other towns] | [73][61][47][74][58][69] |

| Saracinus de Meduna | Saracino | |||

| 1305 | Franciscus de Meduna | [1] | ||

| 1308 | Valmotus de Meduna | Welmotus | [61] | |

| 1308- 338 | Vermeglus di Meduna | Vermeglio, Vermiglio, Vermilio, Virmileo, Vernilio della / de Meduna | 'gastaldio di Meduna', received gastaldia of S. Vito on 5 December 1338, died in Meduna | [62][47][43][45][61][69][75][65] |

| 1351 | Nicoletto di Meduna | son of the late Vermeglus | [76][77] | |

| 1317 | Guinetto di Meduna | 'gastaldio di Aviano' | [34][47] | |

| 1318-1357 | Domenico di Meduna | da Meduna | captured and released on bail on 20 August 1318 | [65][78] |

| 1357 | Grazia da Meduna | widow (daughter?) of the late Domenico | [78] | |

| 1320-1396 | Zanthomasius de Meduna | Zantomasso di Meduna | [34][61][47] | |

| 1321 | Leonino di Meduna | de la Meduna | notary | [34][61][70] |

| 1327 | Lavinio di Meduna | banished by the Patriarch of Aquileia in 1327 (along with Floriamontus and Nicolaus) after their rebellion | [34][47] | |

| Varnero di Meduna | ||||

| 1328 | Rizzardo di Meduna | [70] | ||

| Marquardo di Meduna | son of Rizzardo | |||

| 1328 | Lauro da Meduna | della Meduna | [34][47] | |

| 1330 | Moreto di Meduna | Moretto, Morotto de la Meduna, de Methuna | [79][44][45][48][49][34][47][69] | |

| Nicolaus di Meduna | Nicolò, de la Meduna, de Methuna | son of Moreto, banished by the Patriarch of Aquileia in 1327 (along with Lavinio, Varnero and Floriamontus) after their rebellion | ||

| 1365 | Jacobus de Meduna | member of the Parliament of Friuli | [80] | |

| 1336-1357 | Bianchino di Meduna | da Meduna | son of Francesco straçolinus, received feudal investiture on 27 October 1336 | [65][81][47] |

| 1339 | Tolberto di Meduna | received feudal investiture on 2 January 1339 | [47][65] | |

| 1359-1369 | Comutinus della Meduna | Comuzio | Vicedominus | [54][61] |

| 1359 | Morettino della Meduna | [54] | ||

| 1360 | Leonardo di Meduna | received feudal investiture of Meduna on 7 May 1360 | [65] | |

| Ottussio di Meduna | ||||

| 1360-1370 | Thomassius de Meduna | Thomasinus, Thomasius | [82][83] | |

| Nicolussius de Meduna | Nicolusius | son of Thomassius, notary in San Daniele | ||

| 1369 | Moretto de Meduna | [61][54] | ||

| 1369-1398 | Johannes de Meduna | Giovanni | son of Moretto, received feudal investiture in Portgruaro on 12 July 1382, capitano of Gemona in 1398 | [61][54][65][84] |

| 1355-1365 | Iohannes de Meduna | Giovanni da Meduna | Venice, parish of Saint Antoninus | [85] |

| Mina de Meduna | widow of Iohannes | |||

| 1392 | Donna Abbondanza | daughter of the late Giovanni da Meduna | [86] | |

| 1368-1374 | Pietro Sartore della Meduna | Petro, de la Meduna | teacher, rector of the grammar schools of Portogruaro | |

| Artico di Meduna | friar, prior of the hospital of S. Leonardo di Sacile | [34] | ||

| 1378 | Martinus de Metuna | [89][90][91] | ||

| Grigorius de Metuna | son of Martinus, witness in Valvasone | |||

| 1385 | Giovanni Leone di Meduna | [34][54] | ||

| Vermillino di Meduna |

Castello di Meduno

[edit]The castle of Meduno (Medun) was erected in 1136 under the jurisdiction and upon the wishes of the Bishop of Concordia on its homonymous hill.[10] The name of the castle is attested in 1136 as "Medunum castrum", in a bull of Pope Urban III dated 1186 as "castellum de Meduno cum villa",[92] and in 1191 as "gastaldia de Medurico (…) castro et villa Medunii" (with "Medurico" having been identified in the literature as a manurscript mistake).[39][10][1]

Having been damaged by an earthquake in 1776, the castle was abandoned, and its square stones were used as building material in the nearby village, including the parish church and its bell tower as well as surrounding houses.[93][10]

The current town Meduno developed at the foot of the castle and is one of the oldest centres in the mountain and foothills area. Yet geographically and juridically the elevated Castello di Medun(o) and the Vila de Medun below remained distinct urban structures.[10][94] As with the castello di Meduna and the town of Meduna (di Livenza) further downstream, the toponym of Meduno is related to the river connecting both castles.

Meduno ancestral lineage

[edit]The custody of the castle was entrusted to a ministerial family or dinestemanni – a Germanic term in the oldest available documents. The entrusted nobles, the Counts of Meduno, who lived in the castle and ruled it on behalf of the diocesan Church, were vassals of the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of German Nation and of the Church of Concordia.[63] As such, the family was never present in the parliament, where the Bishop had representation for all his castles. However, they had to pay the See a war bounty.[10][63][94][95][96][97][39][33][98]

In 1312, it is documented that the castellans of Meduno were freed by the Bishop of Concordia from the "ignoble ministry of catching and arresting the thieves" they were bound by the debt of their fiefdom. They achieved this through the eloquence of their associate Thomas, thus erasing this stain from the house of Meduno.[47]

The lords of Meduno had the right to install the Bishops of Concordia (1318: “The horse of the bishop of Concordia is due to the lords of Meduno on the day of his death, because they are the ones who place him in the bishopric”).[99][96][47]

In 1318, the counts of Meduno fought a violent war to gain primacy over the rival Maniaco (Maniago) family. A year later, Walterus, Thomasius and Franciscus di Meduno made peace with the lords of Maniaco.[1][47][100][65]

In 1363, the castle suffered considerable damage after being attacked by the lords of Spilimbergo, Strassoldo, Prata, Polcenigo and Urusbergo, who had sided with Rudolph, Duke of Austria, against Patriarch Lodovico della Torre. During the bitter conflicts which beleaguered Friuli under Patriarchal rule, the lords of Meduno frequently took the side of the counts of Cividale.[101][102][103]

In the 1380s, the nobles of Meduno unsuccessfully sided with the Udinesi against Patriarch Philip of Alençon and Lord of Padua Francesco da Carrara, heralding their gradual decline and division within the family: Giovanni, son of Odorico di Meduno, along with his brothers and associates, rebelled and killed Giacomuzzo and Tomasutto di Meduno. In 1389 the Bishop forcefully took possession of the castle, while Giovanni resorted to an alliance with Cividale, obtaining 300 gold ducats from the community in 1392.[98]

Passed as investiture for 700 gold ducats to the Valentinis family in 1413 by the Bishop of Concordia Enrico di Strassoldo,[54] through a series of alliances and acquisitions the castle returned to the counts of Meduno: On 13 December 1448, Bishop Battista dal Legname once again conferred the investiture of the castle and subject lands and villas to the lords of Meduno – Nicolò, son of Candido, and Antonio, son of Gaspare – for 1300 gold ducats. The family also received the privilege of jurisdiction of the entire lordship in times of vacancy of the See. The castle remained, albeit between various events, in the possession of the Meduno family until 15 September 1514 when the last lord of Medun, Melchiore di Meduno, assigned all assets and rights to his adopted sister's son, Vincenzo Furlano, son of Piero Antonio de Colossis of S. Vito, marking the extinction of the di Meduno lineage and subsequent transfer of the territory under direct administration by the Republic of Venice.[101][102][103][42][104][98]

Historical mentions

[edit]The following is a list of members of the Meduno family mentioned in historical records (until extinction):

| Year | Name | Alternative spelling | Details | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1136 | Wodalricus de Medun | Ulrich | [95] | |

| 1136, 1146 | Gerungus de Meduno | Gerung, Gerunc de Midhuna | Aquileia | [39][33] |

| 1140 | Hermanus de Meduno | Ermanno di Meduno | witnessed the foundation deed of the municipality of Portogruaro | [63] |

| 1186 | Thomas de Meduno | [42] | ||

| Francisco de Meduno | ||||

| Moreto de Meduno | ||||

| Jacobo de Meduno | ||||

| 1189 | Enricus de Medunio | Enrico | [39] | |

| 1191 | Sifredus de Meduno | [39][42] | ||

| 1210 | Artuicus de Meduno | Artico | [42] | |

| 1220 | Corrado di Meduno | [57] | ||

| 1278 | Paulo de Meduno | [60] | ||

| 1295 | Warnerio di Medun | [98][75] | ||

| 1280-1295 | Tommaso di Medun | son of Warnerio, married to Elisa, daughter of Sivrido di Toppo | ||

| Romilda di Meduno | married to Brisino di Toppo | [62] | ||

| 1293 | Ermano di Meduno | [62] | ||

| 1295-1323 | Matheus de Miduno | Matheo | presbyter | [39][1] |

| 1295-1355 | Odorico di Meduno | de Miduno | [62][105][106] | |

| 14th century | Florissa de Meduno | [1] | ||

| 1303 | Syuridus dictus Boça de Miduno | [1] | ||

| Bratus de Miduno | ||||

| Jacobus Germanii de Miduno | ||||

| Walteraia de Miduno | ||||

| 1317-1319 | Conradus de Miduno | [1] | ||

| 1314-1323 | Hermannus de Miduno | Ermanno da Meduno | [1][66] | |

| Andrea de Miduno | sons of Hermannus | |||

| 1318-1343 | Franciscus de Miduno | Francischus de Metuno, Francesco | [1][47][66][100] | |

| 1314-1323 | Sacerdotus de Miduno | [1][66] | ||

| Dominicus de Miduno | son of Sacerdotus | |||

| 1314-1323 | Articus de Miduno | Artico | with Franciscus and Thomasuttus, 'signori di Meduno' | [1][47] |

| Varnerius de Metuno | [47] | |||

| 1318-1343 | Thomasuttus de Miduno | Tomasutto, de Metuno | son of the late Varnerius, with Franciscus and Articus, 'signori di Meduno' | |

| 1314-1339 | Articonus de Miduno | Artichonus, Articone da Meduno, Articon di Meduno, di Medun | 'gastaldio' | [1][42][66][98] |

| 1353-1377 | Giacomo di Medun | son of Articonus, capitano of Solimbergo | [107][108][98][70] | |

| 1377 | Iacobo di Meduno | son of Articonus | [70][98] | |

| Filippa di Meduno | wife of Iacobo | |||

| Daniele di Meduno | heirs and children of Iacobo | |||

| Bortolo di Meduno | ||||

| Odorico di Meduno | ||||

| Articone Giacomo Benvenuta di Meduno | ||||

| Maddalena di Meduno | ||||

| 1319-1331 | Walterius dictus Misotus de Meduno | Vualterius, Walterus, Waltero di Meduno | with Franciscus and Thomasius, made peace with the lords of Maniaco in 1319. | [1][47][100][68][109] |

| Francesco da Meduno | Francesco (di) Misotto da Meduno | son of Misotto, trusted advisor of Patriarch Bertrando | [110][111][112] | |

| 1319, 1339 | Thomasius de Miduno | Tommaso, Thomas, de Meduno | with Franciscus and Walterius, made peace with the lords of Maniaco in 1319. 'D.nus Thomas de Castro Meduni' | [1][47][100][42] |

| 1314-1323 | Franciscuttus de Miduno | sons of Thomasius | [1] | |

| 1337 | Andrea da Medun | [1][42] | ||

| 1339 | Alexander de Meduno | [42] | ||

| 1343 | Marquardo di Meduno | Marquardus de Meduno | presbyter, appointed by the Patriarch as chaplain of the church of Santa Maria in Castel d'Aviano, diocese of Concordia | [112][113][114] |

| 1354 | Stefano di Medun | son of Thomasius | [98][70] | |

| 1357 | Gregorio di Meduno | received feudal investiture in Udine on 29 November 1357 | [54][65] | |

| 1367 | Nicolò da Meduno | notary | [115] | |

| 1377 | Vivianus Malis de Meduno | Vivyanus, Vivianus, Viviano Malis, da Meduno | [42][1] | |

| Guido Malis da Meduno | [116] | |||

| 1382 | G[...] di Meduno | invested by Patriarch Philip of Alençon with two feudal fields in Orcignoco (Orcenico), already owned by his father and deceased uncles | [54] | |

| 1386 | Henricus comare de Meduno | [1] | ||

| 1387 | Jacomuzzo di Meduno | “treacherously killed by their other Consorts; buried in the Church of S. Martino near the Castle of Meduno” (wrapped in sheepskin according to custom) | [54][117] | |

| Tomasutto di Meduno | ||||

| 1391-1392 | Giovanni di Meduno | 'il piccolo' | son of Odorico (see 1377), killed Jacomuzzo and Tomasutto | [42][54][98] |

| 1398-99 | Zuan di Medun | [1] | ||

| 1402 | Vualter de Meduno | [42] | ||

| Andrea de Meduno | son of Vualter | |||

| 1406 | Gio di Meduno | [118][60] | ||

| Candido di Meduno | son of Gio | |||

| Sara di Meduno | wife of Candido | |||

| c. 1420 | Iacomucio di Meduno | [119] | ||

| Dorotea di Meduno | daughter of Iacomucio | |||

| 1438-1448 | Nicolò di Medun | Nicolao | son of Candido (see Meduno until 1420) | [70][98][60] |

| Gaspare di Medun | ||||

| 1448-1487 | Antonio di Medun | di Meduno | son of Gaspare, priest, 'ab immanissimis Turcis abductus est' (abducted by Turks) | [70][98][120] |

| 1485 | Nicolò da Meduno | rector in Coseano | [121] | |

| 1489 | Petrus Faba di Meduno | [42] | ||

| Francesco di Medun | son of Antonio | [98] | ||

| 1514† | Melchiore di Meduno | son of Antonio, the last lord of Medun, adopted his nephew Vincenzo Colossis of S. Vito, marking the extinction of the di Meduno lineage | [42][98] |

Serenissima to Risorgimento

[edit]During the Late Middle Ages and before the 15th century, the Meduna family had left the castle and fiefdom of their surname and settled in localities within the region, including in Pordenone and Treviso, while a branch still continued to live in Meduna in the 15th century.[4] The community retained a seat in the parliament.[118]

The original prepositions of the noble ancestral lineage of the di Meduna family have been increasingly abandoned over time, simply replaced by the surname Meduna, and occasionally supplemented by the place of residence (e.g. Meduna di/della Motta, Meduna di Pordenone).

Feudal investiture of Meduna

[edit]After the Venetian conquest of Friuli and the end of the Patriarchate of Aquilea in 1420, the gastaldia of Meduna was confiscated by the tax authorities and became subject to the Republic of Venice (the “Serenissima”) on 29 May 1420, which subsequently reassigned it to varoious capitani from other noble families for administration.[4]

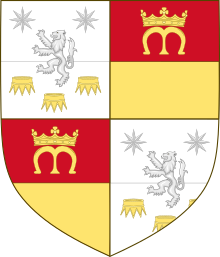

During the rule of the Venetian Republic in Friuli, noble families invested (as capitani, per carati) with the jurisdiction of the castle and community of Meduna, would often attach a toponymic predicate of (conti, signori, or consignori) di/dalla Meduna to their name and adopt and integrate heraldic elements of Meduna in their respective coats of arms.[35]

For example, on 22 May 1455, Meduna was assigned to the patrician Michiel family of Venice – henceforth called Michiel dalla Meduna, which (unlike the earlier patriarchal stewards) maintained control of the fiefdom through inheritance until around 1700.[35]

Families that were invested with the jurisdiction of the castello and the gastaldia of Meduna include the following:[34][122]

- Alberghetti

- Albrizzi

- Avanzo

- Bellan

- Bettini

- Bondenti

- Burlina

- Buzzacarini

- Chiandusso

- Cigolotti

- Cittadella (Vigodarzere)

- Conducini

- Domini (di Orcenigo)

- Duolo

- (H)Erbassica (Barbasecca)

- Fabris

- Fanzago

- Franzani

- Girardi

- Grimaldi

- Lechi

- Locatello (Locatelli)

- Lorando

- Matiuzzi

- Michiel

- Pelizzari

- Perocco

- Pinali

- Provaglio

- Salvi

- Scanagatti

- Simonini (di Udine)

- Zanella

- Zoppola

These families are not to be confused with the original (di) Meduna family that carries the toponym as their surname and established various branches descending from the ancestral lineage.

Pordenone branch

[edit]In the 15th century, some members of the Meduna family had moved north from their ancestral feud and became one of the most prominent and historically most recorded branches of the Meduna family under the Venetian Republic. They were the noble Meduna di Pordenone – established in this town since around 1500, they owned a palazzo at today's Corso Vittorio Emanuele II n. 17, the altar of S. Maria, a sepulchre, and several tombstones at the Cathedral of San Marco, as well as a seat in the city council of Pordenone. In the 16th century, this branch was still linked to properties in the ancestral feud of Meduna.[118]

Many men of this branch were members of the clergy (as well as Franciscans of the Order of Friars Minor Conventual) during the 16th and 17th centuries – including the Reformation period, which quickly collapsed in Italy at the beginning of the 17th century.

During the trial of Claudio Rorario in 1591, Giovanni Battista Meduna of Pordenone, who associated closely with the Mantica and the Rorario families, testified before the Inquisition as a witness about the Mantica-Rorario heretical circle.[123][124] The Mantica and Rorario families both also had their palazzos at Corso Vittorio Emanuele II.[125]

The presence of members of the Meduna family in Motta di Livenza (e.g. Bartolomeo Meduna) and Udine (e.g. Stefano Meduna) is directly linked to the Pordenone branch. The Pordenone branch is reported to have died out at the end of the 1600s, although individuals with noble titles and the name Meduna are recorded in Pordenone still in the 18th century.[118]

Historical mentions

[edit]The following is a list of members of the Pordenone branch of the Meduna family mentioned in historical records:

| Year | Name | Alternative spelling | Details | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominicus Metuna de Portunaone | [126] | |||

| 1528 | Herminius Metuna de Portunaone | Erminio Meduna di Pordenone | son of Dominicus | |

| 1541 | Matteo della Meduna | Maphei, della Meduna da Bergamo, Matteo di Bergamo | son of Domenico della Meduna, cleric, takes possession of the chapel of Santa Maria in the church of San Marco in Pordenone | [127][126][118][128][81][129] |

| 1556-1560 | Defendente della Meduna[130] | a Meduna, da Meduna | son(s) of Matteo, Alessandro was the guardian of his nephews Giovanni Battista, Matteo and Giovanni Maria, the sons of his brother Giovanni Antonio, see tombstone | |

| 1517-1560 | Alessandro della Meduna | |||

| (1602) | Maria della Meduna | daughter of Alessandro, wife of Antonio Piccolo | [128] | |

| 1540-1612 | Giovanni Maria della Meduna | de la Methuna (di Varmo), Meduna Varmo | adopted son and heir of Alessandro della Meduna, priest in Azzano | [118][128][81] |

| Caterina della Meduna | wife of Giovanni Maria, daughter of the lords of Varmo di Sotto | |||

| 1515-1564 | Giovanni Antonio della Meduna | a Meduna, de la Methuna | son of Matteo, brother of Alessandro, resident of Pordenone, scholar of the diocese of Concordia, listed in several notary deeds as the buyer and rentier of a large amount of property assets (on several, also acting on behalf of his brother Alessandro) | [126][128][81][129] |

| 1531 | Anna de Metuna | Antonia, di Meduna | wife of 'Giovanni Antonio B.' (see tombstone) | [127][126][118] |

| 1548 | Giovanni Battista Meduna | sons of Giovanni Antonio | [81] | |

| 1589 | Giovanni Maria Meduna | |||

| 16th century | Matteo Meduna | |||

| 1541-1577 | Francesco della Meduna | [81][131] | ||

| 1546-1570 | [Giovanni] Domenico Meduna | a Meduna, della Meduna | [118][128][81] | |

| 1592 | [...] Maria della Meduna | son of Matteo | [81] | |

| Liberale Meduna | son of Francesco | [118][131] | ||

| 1629 | Aloisia Meduna | daughter of Liberale | ||

| 1584-1587 | Domicio Meduna | son of Domenico | [81] | |

| 1562-1605† | Stefano Meduna | [son of Domenico,] brother of Giovanni Battista, Pordenone, "and among the notable men of this family was Stefano, a most excellent lawyer and leader, who died in 1605. This one came to live in Udine, and was accepted first as Noble of the Council" | [132][133][134] | |

| 1616 | Giovanni Maria Meduna | son of Domenico, cleric | [135][118][136][137][123][81][42][138][126] | |

| 1574-1613 | Giovanni Battista Meduna | Ioannis Baptista, Zambattista, Methuna, Mettuna, Meduna di Pordenone | son of Domenico, cleric, presbyter, appointed by Bishop Michele della Torre and placed in possession of the church of San Giacomo in Brugnera, invested by the Bishop of Concordia Pietro Querini (on the orders of the Roman Curia) as parish priest and vicar of the church of San Pietro in Azzano, vicar of the cathedral of San Marco in Pordenone, and rector of the church of San Giovanni in San Quirino until 16 June 1605 | |

| 1572-1618† | Bartolomeo Meduna | Bartholomaus, Borchio, Metuna (della Motta, Methensis, Metensis) | son of Giovanni Battista, Franciscan (O.F.M.Conv.) cleric, scholar, teacher, and author, Guardian and Custos of the convent of Motta, Convents of Friuli, and the convent of Udine, author of two operettas in Italian, died on 15 November 1618 | [135][4][139][133][140][132][141][142][143][144][145][146][147][148][149][150] |

| 1668 | Francesco Meduna | Francesco Gasparotto dalla Meduna | brother of Bartolomeo, physician, "performs miraculous works in medical matters" | [133][4][151] |

| 1601-1644† | Alessandro Meduna | Aleandro, Meduna di Motta | brother or nephew of Bartolomeo, Franciscan (O.F.M.Conv.) cleric, professor of theology, ordained on 10 February 1601, Custos of the Convent in Udine since 1617 and Guardian since 1626, elected Prrovincial Minister of the Order's Province of Sant'Antonio in 1636, died on 17 April 1644 | [140][132][150][152] |

| 1586-1611 | Torquato Meduna | cousin of Bartolomeo | [133][128] | |

| 1551-1557 | Vincentius de Metuna | prefect of the Dominican monastery of Capodistria | [153] | |

| 1556 | Stephanus Locatellus Meduna[154] | Stephano, Locattellus, Metuna, Methuna | son of Defendo (Defendente), Pordenone, Friuli; received a privilegium doctoratus (doctorate diploma degree in law) at the University of Padua on 2 February 1556, examinded and approved on 9 March 1556. | [155] |

| Silvester Grimaldus de Metuna | Silvestro Grimaldo a Methuna | son of Baptiste (Battista), Pordenone, Friuli; received a privilegium doctoratus (doctorate diploma degree in law) at the University of Padua on 23 April 1556, examinded and approved on 2 May 1556. | ||

| Petrus Grimaldus de Metuna | Friulian scholar of law at the University of Padua | |||

| 1558-1595 | Mario della Meduna di Pordenone | [128] | ||

| 1620 | Alessandra | Donna Aleandra | widow of Mario Meduna, daughter of Battista Aleandri (surgeon in Pordenone), died in San Quirino | [118][128] |

| 1579-1587 | Daniel da la Meduna | de Meduna | Franciscan (O.F.M.Conv.) friar from the Order's Province of Sant'Antonio, under General Gonzaga, 1579-1587 in the Paris Chapter, 1583 the Order's Procurator at Rome, 1584 in the Toledo Congregation, under the same General Gonzaga | [156][157][158] |

| 1592-1608 | Girolamo Meduna | zoccolante (clogs-wearing monk), Guardian of Motta | [159][140] | |

| 1595-1602 | Arminius Meduna | Erminio, Flaminio | priest, chaplain in Fagnigola, Pordenone | [137] |

| 17th century | Mauritius Meduna | Maurizio | presbyter | [81] |

| 1624 | Domenico Meduna | children of Mauritius | [128][81] | |

| [Dainia] Meduna | ||||

| 1623-1685 | Antonio Meduna | Methuna, Meduna da Motta | son of Mauritius, nobleman from Pordenone, notary in Feltre, Capodistria and Argostoli (in Cephalonia), appointed on 6 May 1672 cancelliere by Andrea Valiero, Venice's Provveditore Generale da Mar, as successor to Simone Budini | [126][81][128][160] |

| 1632-1678† | Michele Aurelio Meduna di Pordenone | Meduna di Motta | Franciscan (O.F.M.Conv.) cleric, Guardian of the Convents in Costozza, Gemona, Montebello, and Pordenone, died on 18 September 1678 | [140][150] |

| 1658-1659 | Ascanio Meduna | brothers | [128] | |

| Giovanni Maria Meduna | ||||

| 1705† | Giovanni della Meduna | rector of the church of San Giorgio in Pordenone | [128] | |

| 1733† | Fiorina Meduna | [118] | ||

| 1744 | Giovanni Maria Meduna | Gio. Maria | parish priest and vicar forane[161] of the church of San Giorgio in Pordenone | [126][162] |

| 1746-1825 | Pasconi di Meduna | [128] | ||

| 1755 | Mauritius Methuna | City Council of Pordenone ('Consilium Civitatis Portusnaonis') | [138] | |

| 1755† | Domenico Meduna | [118] | ||

Venetian branch

[edit]Notable members of the family that lived and worked in Venice during the era of the Risorgimento were the architect Giovanni Battista Meduna (1800-1886) and his brother, engineer Tommaso Meduna (1798-1880), sons of carpenter and window maker Andrea Meduna.[163][164][165][166]

Giovanni Battista Meduna is buried at the San Michele Cemetery along with his wife Maria Viola (1805-1866) and their two sons Leopoldo (1837-1855) and Cesare Meduna (1841-1906), ending this particular lineage.

Treviso-Castelcucco branch

[edit]Another branch of the family moved south-west from their ancestral feud to Treviso, where they became citizens – attested as early as in the first decades of the 14th century (see historical mentions). This time coincides with the conspiracy attempt of the castellans of Meduna to sell the castle to Rizzardo da Camino, lord of the Treviso area, resulting in their banishment from the Meduna fief in 1327.

The arrival of members of the Treviso branch in nearby Castelcucco is reported in the first decades of the 16th century. The Meduna of Castelcucco (as well as neighboring Asolo and surrounding areas) owned a mansion below the one of the Montini family along the Via Lungo Muson.

A splendid example of eighteenth-century artchitecture, the mansion passed from the Meduna to the Malafatti family, and in 1739 to the Perusini d'Asolo. In 1801, Naopoleon Bonaparte stayed at the villa, known today as Villa Perusini. The property subsequently passed to monsignore Pietro Basso, then the Pivetta family, then to cavaliere Lucio Pinarello at the beginning of the 20th century, subsequently to the Filippins and finally to Mr. Andreatta. For many years it was the residence of the famous writer Sergio Saviane, who died in 2001. The villa was once adorned with many surrounding gardens with fountains and water jets, which had been lost over the years. The small church of San Francesco is connected to the villa via a covered passage.[167][168][169]

In 1776, the Meduna family also obtained from the Dall'Armi family the church of San Gaetano (dating back to the 5th and 6th centuries), together with its altarpiece, along the main road in Castelcucco. It, too, passed to the Perusini in 1805, to the noble Colbertaldo family in 1875, then again to the nobles of Meduna, and then to the Colferai. In 1936, the church was sold to Antonio Signor, who subsequently donated it to the parish of Castelcucco.[170][171][172]

Historical mentions

[edit]The following is a list of members of the Treviso-Castelcucco branch of the Meduna family mentioned in historical records:

| Year | Name | Alternative spelling | Details | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1315 | Stefano della Meduna | salaryman of the municipality of Treviso | [173] | |

| 1318 | Jacobus de Meduna | knight in Treviso, confirmed unanimously by 31 councilors as constable with 25 horsemen with helms and as many crossbowmen and squires with lances | ||

| 1523-1557 | Girolamo della Meduna di Treviso | [167] | ||

| Girolamo (II) della Meduna di Treviso | Gerolamo | son of Girolamo, resident of Longamuson, has purchased this property already from 1523 onwards from Dorigo son of Guarnerio Zardo from Crespano | ||

| 1562 | Antonia | daughter of the painter Leonardo da Verona living in Borgo Santa Caterina in Asolo, widow of Girolamo (II) Meduna, citizen of Treviso | [167] | |

| Giovanni Meduna | son of Girolamo (II), stepson of Antonia, half-brother of Giacomo and Bartolomeo | |||

| 1592 | Ludovico Meduna | son of Giovanni, priest of the church of San Giorgio in Castelcucco | [167] | |

| 1580 | Giacomo Metuna | da Meduna | member of the college of judges of Treviso | [174][175] |

| 1621-1642 | Vincenzo Meduna | Metuna, Meduno [sic!] | parish priest of Sant'Ambrogio di Fiera in Treviso (1621-1626), nominated as public tutor (precettore) in Pordenone in 1623 (did not accept), priest in Savorgnano, Udine (1630-1642) | [176][126][177][162] |

| 1670 | Paolo Francesco Meduna | nephew of Ludovico, priest of the church of San Giorgio (after his uncle) until 1670 | [167] | |

| 1715 | Antonio Meduna | [178] | ||

| Paolo Meduna | son of Antonio, descends from ancient citizens of Treviso, resident at Castelcucco Nr. 33, Col di Muson (Villa Meduna) | |||

| 18th century | Giovanni Paolo Meduna | Paolo, Gio. Paolo, Gian Paolo, Gian-Paolo, Giampaolo | abbot, poet, professor of belles-lettres at the Treviso Seminary, then of eloquence at the Feltre Seminary, author of academic works and poems in praise of Canova and an oriental hymn as an epithalamium for Napoleon's wedding to Marie Louise ("Per l'Augusto Imeneo"), provost of Asolo, archpriest of Monfumo, died 28 June 1835 in Vicenza | [179][180] |

| 1810-1835† | [181][182][183][184][185][186][187][188][189][190][191][192][193] | |||

| 1848 | Paolo Meduna | member of the Municipal Representation of Asolo | [194] | |

| 1824-1857† | Fortunato Meduna | born 1824, mansionario and confessore at the Duomo di Asolo, died 2 July 1857 | [195][185] | |

| 1868-1871 | Severo Meduna | [167] | ||

| Francesco Meduna | son of the late Severo, landowner, born in 1828, mayor of Castelcucco, unmarried, living with his sisters, moved to Paderno in 1905, where he owned the osteria near the San Giacomo hotel |

The first census of Italy in 1871 only records the family of Francesco Meduna, son of Severo, in Castelcucco . As mayor of Castelcucco in 1868, Francesco Meduna raised funds for the Consorzio Nazionale, established by king Victor Emmanuel II in 1866 as a fund for the amortization of national debt, as well as for the wedding of crown prince Umberto and his first cousin Margherita of Savoy.[167][196]

His brother Giuseppe Carlo Meduna (1821–1895) emigrated to Budapest, Hungary, in the first half of the nineteenth century, where he became an award-winning salami maker and progenitor of the Hungarian branch of the Meduna family.

In Hungary, he used the noble title von Meduna, Edler v. Montecucco.[197] Members of this branch are mentioned in several Austro-Hungarian records as Meduna di Montecucco. One of his grandchildren was renowned neuropathologist and neuropsychiatrist Ladislas J. Meduna (1896–1964).[198][199][200]

Lands of the Bohemian Crown

[edit]The first record of the name Meduna outside of Italy appears in 1373 in the village of Bohuslavice, in today's Vysočina Region of the Czech Republic. A certain Mixo (Mikeš, Niklaš) called Meduna and his brother Swathon (Svatoň, Šwach) bought a feudal estate (manor) from Hron of Bohuslavice. However, this appears to be a nickname rather than a family name. Meduna as a definitve hereditary surname first appears in the 16th century in the Lands of the Bohemian Crown, at a time when the Protestant Reformation heralded the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the early modern period in Europe.[201][202][203]

Melissaeus priests

[edit]A family of Utraquist Hussite priests appears in the second half of the 16th century in North and Central Bohemia: Jakub Melissaeus Krtský (1554–1599), Václav Melissaeus Krtský (1540–1578), and Václav Melissaeus Lounský (c. 1573–1631).

Their surname "Melissaeus" is an onomastic latinisation (common in scholarly and clerical circles of the time) of the name Meduna resulting from the Ancient Greek Melisseus (Μελισσεύς), based on the local interpretation of the name being related to honey (med in Czech) or Melissa (lemon balm, meduňka in Czech). Several modern Czech sources revert to the non-Latin version and refer to the Melissaeus priests explicitly as Meduna.[204][205][206][207][208][209][210][211][212]

East-Bohemian branch

[edit]When the Peace of Westphalia ended the Thirty Years' War in Europe, the Habsburg Empire begann to reassert their power and sought to re-Catholicize the Protestant-leaning Lands of the Bohemian Crown. In order to determine where best to focus their proselytizing efforts of the Counter-Reformation, a detailed census was needed. To this end, Patents were issued in February and June of 1651 that directed the Bohemian Estates to record the names and religious denominations of all persons within their dominions on standardized forms, referred to as the List of Subjects According to Their Faith (serfs register).[213]

Historical mentions: Seč estate

[edit]Of the 19 regions of Bohemia covered in the List of Subjects, a family of the name Meduna is mentioned only on the Seč estate in the East-Bohemian Chrudim District.[214] The estate was owned in 1651 by Emanuele de Couriers, who inherited it from his father François de Couriers, a French nobleman by origin and an officer of the imperial Habsburg army. He bought Seč (in 1628) and other estates cheaply from confiscations following the Battle of White Mountain, after the previous owners who participated in the Bohemian Revolt were forced into exile.The dominions of Seč and Nasavrky (purchased by de Couriers in 1623) were among the least religiously united territories, with the share of non-Catholics exceeding 80%.[215]

| Region | Estate | Locality | Name | Year of birth | Description | Faith | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chrudim | Seč | Bojanov | Martin Meduna | 1621 | podruh | non-Catholic | |

| Chrudim | Seč | Bojanov | Magdalena Meduna | 1620 | wife of Martin | non-Catholic | |

| Chrudim | Seč | Bojanov | Jakub Meduna | 1633 | son of Martin | non-Catholic | |

| Chrudim | Seč | Bojanov | Václav Meduna | 1636 | son of Martin | non-Catholic | A |

| Chrudim | Seč | [Nové] Lhotice | Adam Meduna | 1595 | chalupník | non-Catholic | |

| Chrudim | Seč | [Nové] Lhotice | Lidmilla Meduna | 1627 | wife of Adam | non-Catholic | |

| Chrudim | Seč | Křižanovice | Jan Meduna | 1620 | sedlák | non-Catholic | B |

| Chrudim | Seč | Křižanovice | Anna Meduna | 1630 | wife of Jan | non-Catholic | |

| Chrudim | Seč | Křižanovice | Jiřík Meduna | 1618 | chalupník | non-Catholic | |

| Chrudim | Seč | Křižanovice | Kateřina Meduna | 1629 | wife of Jiřík | non-Catholic | |

| Chrudim | Seč | Křižanovice | Anna Meduna | 1635 | daughter of Jiřík | non-Catholic | |

| Chrudim | Seč | Liboměřice | Václav Meduna | 1613 | sedlák | non-Catholic | C, D |

| Chrudim | Seč | Liboměřice | Kateřina Meduna | 1625 | wife of Václav | non-Catholic | |

| ABC Entries also to be found in the 1654 Berní rula (see below). D Secret protestant services were held in the Meduna barn in Liboměřice Nr. 8 until the Patent of Toleration in 1781.[216][217] | |||||||

Since the 17th century, this region developed as the historical epicenter of the Meduna family in the Czech lands, and to this day the name remains most prevalent in Chrudim District. Several existing branches of the Meduna family in Austria as well as the United States trace back their lineages to the East-Bohemian branch.[6][7]

In 1654, the Crown ordered a record of all taxable subjects (property-owning population) in Bohema, known as the Berní rula.[218] In addition to members of the Meduna family on the Seč estate recorded three years earlier, the Berní rula mentions a Jakub Meduna from Vltava region and a Václav Meduna of Prague.[219][220]

| Region | Estate | Locality | Name | Description | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vltava | Tejnice, Benice | Chrášťany | Jakub Meduna | zahradník | D |

| Chrudim | Seč | Křižanovice | Jan Meduna | sedlák | B |

| Chrudim | Seč | [Nové] Lhotice | Václav Meduna | sedlák | A |

| Chrudim | Seč | Liboměřice | Václav Meduna | sedlák | C |

| Prague | U Karafiátů | Žatecká street 42 | Václav Meduna | komorník desk. | E |

| Chrudim | Seč | Licibořice | Havel Meduna | chalupnik | |

| ABC Entries also to be found in the 1651 List of Subjects According to Their Faith (see above). D About 10 km north-east from Chrášťany, in the Petroupim municipality a forest, a stream, and a game reserve with the name Meduna (Meduny) are recorded as early as 1409.[221][222][223] E (). | |||||

Historical mentions: Prague

[edit]In 1604, a certain Jakub Meduna from Borová, on the Polná-Přibyslav estate owned by Rudolf Žejdlic of Šenfeld (Seydlitz von Schönfeld), located some 30 km south of the Seč estate, was enrolled at Prague's Charles University.[224][225] In 1611, he is listed as a resident of Prague.[226]

On 21 May 1643, Jan Duchoslav Karafilát bequeathed his house on Žatecká (Kaprov) street Nr. 42 in Prague to his wife Kateřina Barbora. After his passing, the widow married Václav Meduna (listed in the Berní rula), chamberlain at the tabulas regni, and on 17 September 1646 she transferred the house to him. The confession registers from the parish of St. Valentine in the Old Town of Prague – compiled during the re-Catholization period of the Czech lands – list Václav to be 42 years old, and his wife Kateřina 46, both Catholic.[227][228][229]

Meduna von Riedburg

[edit]One notable family descending from the East-Bohemian branch were the Meduna von Riedburg, who trace back their title of nobility to Johann Meduna von Riedburg. Descendants of this family today live in Germany and Brazil, where they emigrated at the beginning of the 20th century.[6]

South-Moravian branch

[edit]The proliferation of the name Meduna in South Moravia begins with Šimon Medoňa († 1698), land owner in Drnovice, Blansko District, in the 1650s. He is recorded not only in the Moravian Lánové rejstříky (1657)[230] – a source comparable to the Bohemian Berní rula, but also in the Moravské a Slezské Urbáře (1677)[231] and in the first local church books.[232]

The surname of his lineage and descendants has most commonly been transcribed in local records as Meduňa/Medoňa, a spelling resulting from palatal consonants in Moravian dialects (e.g. the word day analogously morphs from den in Czech to deň in Moravian). As the only recorded Meduna of his generation in this region, he is the progenitor of the South-Moravian branch of the Meduna family. His two sons Georg (Jiřík) and Jakob (Jakub) Meduňa established family lines that exist until this day, with descendant branches most prominent in the Czech Republic, Austria, the United States and Brazil.[233][234][6]

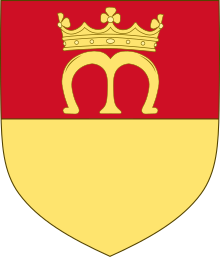

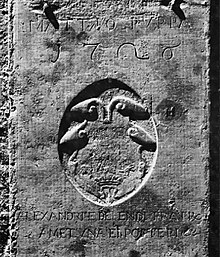

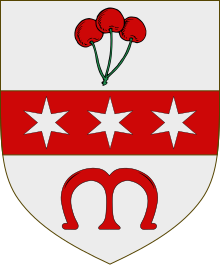

Heraldry

[edit]The coat of arms of the Meduna family went through several iterations over the centuries. Neither the emblem of the ancestral feudal lords of Meduna since their origin in the 11th century until they were banished by the Patriarch in 1327, nor that of the lords of Meduno, is known. The following versions are recorded from the 16th century onwards. Both the family and their homonymous community of origin were often represented by the same coat of arms.

|

|

|

The above coat of arms is reported to be the oldest known heraldic insignium of Meduna, found at the Sanctuary of Madonna dei Miracoli in Motta di Livenza. Goi (1993) describes the charge in the field as alla civetta in maestà accompagnata da 3 stelle (owl facing the beholder accompanied by 3 stars) and observes that the position with the enlarged claws is notable.[118]

It was still in use in the first half of the 16th century, and is identical or nearly identical with the coats of arms of the following families:

- Locatelli of Castelfranco (west of Treviso) and Sicily (as well as their comune of origin, Locatello in Bergamo)[118][236][237]

- Perocco (of Meduna)[238][239]

- Pinali of Pordenone[240]

- Artico of Ceneda (north-east of Meduna di Livenza)

- Simonini of Udine[241][242]

- a certain Pompeo Coronini of Gorizia (north-east of Aquileia)[243][244]

- Mendoza (of Spanish origin)[245]

- Mortari of Genoa[246]

- Lavinia of Filottrano[247]

The shared coat of arms and geographical proximity of most of these families (see for example Matteo della Meduna da Bergamo, the region of origin of the Locatelli) could indicate genealogical relations between them – despite the inheritance of different names – or a feudal relation with the community of Meduna. Some of the above, however, particularly of more remote locations or slight heraldic variations, might well be unrelated.

The owl as a symbol of wisdom is also reminiscent of the iconography in the allegoric emblem of Bartolomeo Meduna: The nymph Meduna is carrying the horn of Amalthea (described as symbolizing scientific progress) and leaning against a threefold mountain of the same name. The water that springs from the mountain (the river Meduna) is described as a source wisdom – analogously to the owl atop the threefold mountain.[133]

|

Since the late 16th century, the below versions start to appear – both as coats of arms of the community of Meduna and the family of this name. A combination with the old owl coat of arms appears in two simple and quartered versions also in the Joppi armorial (n. 403, 922),[236][248] but with the owl placed in natural position, while the two stars on the top remain unchanged, and a letter M poled with a comet on the central leg.[126][118]

|

| |

|

|

In subsequent itarations the owl and the stars disappear. The letter M (in or) on gules tincture – without the comet – is described by Rietstap and depicted in the De Rubeis manuscript (n. 1114).[249][250] A version parted per fess is described by Spreti: a combination of the crowned golden M on red in the upper half with a golden shield in the lower half.[251]

|

|

|

The parted version of the coat of arms became the default heraldic representation subsequently integrated in their coats of arms by other families invested with the jurisdiction of Meduna, for example:

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

Finally, the below three-coloured coat of arms of Meduna is reported since the 18th century, with the traditional parted gules and or tinctures supplemented by a sable one, and without any charges.[253][118] How and why the heraldic emblems transitioned over the centuries is not known – possibly they were representations of related yet distinct branches of the family.

|

|

The contemporary emblem of the comune (municipality) of Meduna di Livenza is yet a different one.[254]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Puntin, Maurizio (2023). Cjanâl da la Miduna: Gli Antichi Nomi della Val Meduna e della Val Colvera e la Poesia di Novella Cantarutti (in Italian). Udine: Società Filologica Friulana; [Montereale Valcellina] : Circolo culturale Menocchio. pp. 313–317. ISBN 978-88-7636-394-8.

- ^ Niger, Dominicus Marius (1517). Geographiae commentariorum libri XI (...) (in Latin). per Henrchum Petri. p. 115.

- ^ a b c Pertz, Georg Heinrich (1906). "Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Diplomata Karolinorum, 1: Pippini, Carlomanni, Caroli Magni Diplomata" (in German and Latin). p. 239 (n. 177). Archived from the original on 2023-03-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rocco, Lepido; Cavagna Sangiuliani di Gualdana, Antonio (1897). Motta di Livenza e suoi dintorni : studio storico (in Italian). University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Treviso : Litografia Sociale della "Gazzetta". pp. 21, 204, 348–349.

- ^ a b c d e f "Comune di Meduna di Livenza: Storia - Medioevo". Comune di Meduna di Livenza (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2022-09-13. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- ^ a b c d e "Meduna Surname Origin, Meaning & Last Name History". forebears.io. Archived from the original on 2023-08-18. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- ^ a b "Příjmení: 'Meduna'". kdejsme.cz (in Czech). Archived from the original on 2022-10-02. Retrieved 2023-08-21.

- ^ There is no evident connection between the European (incl. US, Brazilian) occurrences of Meduna and the Nigerian ones, suggesting a separate local African origin.

- ^ Nebrija, Antonio de (1540). Dictionarium Ael. Antonii Nebrissensis: cum ex alijs eiusdem Autoris commentarijs: tum ex lexico latino nondum edito: varia&multiplici accessione locupletatum; ut dictionum fere omniũ varios usus: significationes: origines: differentias; facile quiuis unius voluminis ope scire valeat (in Latin). Xanthus Nebrissensis.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Goi, Paolo; Antonini Canterin, Luigi (1991). Meduno. Memorie e appunti di storia, arte, vita sociale e religiosa (in Italian). Cassa Rurale ed Artigiana di Meduno. pp. 18–20, 38, 40–41.

- ^ Frau, Giovanni (1969). Pellegrini, Giovan Battista (ed.). "Nomi dei Castelli Friulani". Studi Linguistici Friulani (in Italian). I: 257–315.

- ^ Villar, Francisco; Prósper, Blanca María (2005). Vascos, celtas e indoeuropeos: Genes y lenguas (in Spanish). Universidad de Salamanca. ISBN 978-84-7800-530-7.

- ^ Masson, Jean Papire (1518). Descriptio fluminum Galliae, qua Francia est. Papirii Massoni opera. Nunc primùm in lucem edita, christianissimoque regi dicata (in Latin). apud Iacobum Quesnel, via Iacobaea, sub intersignio Columbarum.

- ^ de Segusia, Henricus (Henry of Susa) (1512). Lectura siue Apparatus domini Hostiensis super quinq[ue] libris Decretaliu[m] (in Latin). p. 230.

- ^ Ciol, Elio e Stefano (2007). Friuli Venezia Giulia. Un percoso tra arte, storia, e natura (in Italian). Cierre edizioni. Circolo culturale Menocchio. p. 84. Archived from the original on 2023-06-26.

- ^ Candido, Giovanni (1544). Comentarii di Giovan Candido Giuresconsulto de i Fatti d'Aquileia (in Italian). M. Tramezino.

- ^ Verein von Altertumsfreunden im Rheinlande (1860). Jahrbücher des Vereins von Altertumsfreunden im Rheinlande (in German). Vol. 29. p. 170.

- ^ Corvina, Q. Albia (7 June 2016). "Antike Stätten: Bertriacum – Römisches Quellheiligtum der Meduna und Vercana (Bad Bertrich)". Mos Maiorum – Der Römische Weg (in German). Archived from the original on 2023-04-04. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- ^ "Geschichte". Herzlich Willkommen in Mettendorf in der Eifel (in German). Archived from the original on 2022-11-29. Retrieved 2022-11-29.

- ^ Rheinisches Jahrbuch für Volkskunde (in German). F. Dümmler. 1952. p. 83.

- ^ Trierer Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Kunst des Trierer Landes und seiner Nachbargebiete (in German). Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier. 1972. pp. 241–243.

- ^ Olivieri, Dante (1961). Toponomastica veneta (in Italian). Istituto per la collaborazione culturale. p. 6. ISBN 978-88-222-2262-6.

- ^ Gasca Queirazza, Giuliano (1990). Dizionario Di Toponomastica: Storia E Significato Dei Nomi Geografici Italiani (in Italian). Internet Archive. Garzanti. p. 387.

- ^ De Agostini (2010). Nomi d'Italia (in Italian). ASIN B00B7YQN1S.

- ^ "14521 Inschrift eines collegium". Ubi Erat Lupa (in German). Archived from the original on 2023-03-28. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- ^ "Città di Modugno: Cenni storici". Città di Modugno (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2023-06-08. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- ^ "Ospitale Civico - Pergamene 5[A]". CDAVr - Codice digitale degli archivi veronesi (VIII-XII secolo), a cura di Andrea Brugnoli. Archived from the original on 2023-09-26.

- ^ King's College London (ed.). "Meduna di Livenza (Matunianus)". The Making of Charlemagne's Europe. Archived from the original on 2023-04-24. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- ^ Centro Interuniversitario per la Storia e l’Archeologia dell’Alto Medioevo (ed.). "Convenientiae: Veneto II". SAAME – Storia e Archeologia Alto Medioevo (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2023-04-24. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- ^ Cippola, Carlo (1901). "Antichi Documenti del Monastero Trevigiano dei SS. Pietro e Teonisto". Bullettino dell'Istituto Storico Italiano per Il Medio Evo e Archivio Muratoriano (in Italian). VII (22). Rome: Istituto storico italiano per il Medio Evo: 63.

- ^ In sources of later provenance, the river is sometimes called "il [fiume] Meduna".

- ^ Peressini, Renzo (2015). Baptizatorum Liber: Il Primo Registro Dei Battesimi Di Santa Maria Maggiore Di Spilimbergo (1534-1603) (in Italian and Latin). Con una nota di Paolo Goi. Pordenone: Accademia San Marco. p. 591. Archived from the original on 2023-04-16.

- ^ a b c "Urkundenbuch des Herzogtums Steiermark: AQ 2 – 1146. Aquileia". gams.uni-graz.at (in German and Latin). Archived from the original on 2021-04-18. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Pizzin, Amedeo (1964). Meduna di Livenza e La Sua Storia (in Italian). Cosarini. pp. 32, 42–46, 51–52, 60–65.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fasan, Mauro (2014). I patrizi veneti Michiel. Storia dei Michiel "dalla Meduna" (in Italian). Rome: ARCANE editrice S.r.l. pp. 42–48. ISBN 978-88-548-7139-7.

- ^ "Comune di Meduna di Livenza: Territorio - Idrografia". Comune di Meduna di Livenza (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2021-09-28. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri (Governo Italiano). "Regio Decreto agosto 1884, n. 2578". Normattiva. Il Portale della Legge Vigente. Archived from the original on 2024-01-01.

- ^ Gelli, Jacopo (1906). Divise-motti e imprese di famiglie e personaggi italiani. Getty Research Institute. Milano : Ulrico Hoepli. p. 547.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Atti del Reale Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti (in Italian). Vol. 8. Reale Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti. 1882. p. 8.

- ^ a b "Comune di Meduna di Livenza: Storia - Cenni storici". Comune di Meduna di Livenza. Archived from the original on 2022-05-06. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ Le Bret, Johann Friedrich (1783). Vorlesungen über die Statistik. Erster Theil. Italiänische [sic!] Staaten (in German). Johann Benedict Mezler. p. 127.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Degani, Ernesto (1924). La diocesi di Concordia (in Italian). pp. 145, 147, 165, 358, 408–409, 415, 418, 422–423, 464, 466, 626–627, 708–709, 746.

- ^ a b c Bassetti, Sandro (2011). Historia Sextij. Dallo Gran Diluvio a Hoggi (in Italian and Latin). Lampi di stampa. pp. 32, 154, 329, 331. ISBN 978-88-488-1201-6.

- ^ a b c d Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften (1869). Archiv für österreichische Geschichte (in German and Latin). Vol. 41. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. pp. 429–430, 435.

- ^ a b c d Bianchi, Giuseppe (1845). Documenti per la Storia del Friuli dal 1326 al 1332 (in Italian and Latin). pp. 30, 32, 66, 107, 406.

- ^ a b c de Rubeis, Bernardo Maria (1740). Monumenta Ecclesiae Aquilejensis. Commentario Historico-Chronologico-Critico Illustrata (in Latin). Vol. II. p. 682.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t di Manzano, Francesco (1862). Annali del Friuli (in Italian). Vol. IV. pp. 10, 64, 72–73, 86, 113, 135, 194, 205, 208, 220, 232, 391, 407, 435, 500.

- ^ a b Jenichen, Gottlob August (1754). Thesaurus Iuris Feudalis (in Latin). p. 352.

- ^ a b Muratori, Lodovico Antonio (1774). Antiquitates Italicae Medii Aevi; Sive Dissertationes (…) (in Latin). p. 354.

- ^ Ciucciovino, Carlo (2011). La Cronaca del Trecento Italiano (PDF) (in Italian). Vol. II: 1326-1350. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-04-18.

- ^ Le Bret, Johann Friedrich (1781). Allgemeine Welthistorie von Anbeginn der Welt bis auf gegenwärtige Zeit. XLIII. Theil. Historie der Neuen Zeiten, XXV. Theil (in German). Johann Justinus Gebauer. pp. 242–243.

- ^ Ecomuseo Lis Aganis: Castello di Meduno, retrieved 2023-08-19

- ^ BUCANEVE Italia: Comune di Meduno | 2015, retrieved 2023-08-19

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k di Manzano, Francesco (1865). Annali del Friuli (in Italian). Vol. V. pp. 74, 150, 181, 253, 258, 270, 361, 419, 465.

- ^ Verci, Giovanni Battista; Cavagna Sangiuliani di Gualdana, Antonio (1786). Storia della Marca Trivigiana e Veronese (in Italian and Latin). Vol. 1–2. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. p. 37.

- ^ Deputazione di Storia Patria per il Friuli (1919). Memorie Storiche Forogiuliesi (in Italian). pp. 8, 37.

- ^ a b c di Manzano, Francesco (1858). Annali del Friuli (in Italian). Vol. II. pp. 270, 283, 354.

- ^ a b c Della Torre, Renato (1979). L'Abbazia di Sesto in Sylvis dalle origini alla fine del '200: introduzione storica e documenti (in Italian and Latin). pp. 187, 252, 360.

- ^ "Veneto Orientale, Mulini e Musei Etnografici". Comune di Pramaggiore (in Italian). 2007-02-02. Archived from the original on 2015-01-08. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ a b c d Fontes rerum Austriacarum: Diplomataria et acta. Zweite Abtheilung (in Latin). Vol. 24. H. Böhlaus Nachf. 1865. pp. 10, 12–15, 24, 228.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Bianchi, Giuseppe (1847). Thesaurus Ecclesiae Aquilejensis (in Latin). pp. 85–87 (n. 136–141), 216 (n. 487–488), 259 (n. 716), 269 (n. 766), 291 (n. 877–878), 308 (n. 1023), 320 (n. 1088), 341–342 (n. 1171, 1177), 344–345 (n. 1186, 1191), 378 (n. 1308).

- ^ a b c d e di Manzano, Francesco (1861). Annali del Friuli (in Italian). Vol. III. pp. 159, 179, 231, 254, 374, 456–457.

- ^ a b c d e Degani, Ernesto (1891). Il Comune di Portogruaro: Sua Origine e Sue Vicende, 1140-1420 (in Italian). pp. 15, 27, 48, 134.

- ^ Archiv für Kunde österreichischer Geschichts-Quellen (in German). Vol. 24. 1860. p. 438.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bianchi, Giuseppe (1877). Indice dei documenti per la storia del Friuli dal 1200 al 1400: Pubblicato per cura del municipio di Udine (in Italian). Tip. J.E. Colmegna. pp. 24, 46, 49, 81, 89, 92, 103–104, 130, 135, 156.

- ^ a b c d e Gianni, Luca (2001). Le note di Guglielmo da Cividale (1314-1323) (in Italian). Istituto Pio Paschini per la Storia della Chiesa in Friuli. pp. 15, 281, 288, 293, 294, 468. ISBN 9788887948097.

- ^ Deputazione di Storia Patria per il Friuli (1930). Memorie Storiche Cividalesi: Bulletino del R. Museo di Cividale (in Italian). Vol. 26–29. Deputazione di storia patria per il Friuli. p. 159.

- ^ a b Archeografo Triestino. Nuova Serie (in Italian). Vol. XV. Editore Società di Minerva. 1890. pp. 204, 212, 226.

- ^ a b c d Bianchi, Giuseppe (1845). Del preteso soggiorno di Dante in Udine od in Tolmino (...) (in Italian and Latin). pp. 12 (n. 428), 46 (n. 444), 87 (n. 469), 706 (p. 417).

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Pagine Friulane". Pagine Friulane. Periodico Mensile. (in Italian). VIII: 32, 52–54. 1896.

- ^ Verci, Giovanni Battista (1789). Storia della Marca Trivigiana e Veronese (in Latin). Vol. 11. Presso Giacomo Storti. pp. 56, 58.

- ^ Leicht, Pier Silverio (1925). Parlamento friulano (in Latin and Italian). Vol. 1, Part 2. Forni. p. 130.

- ^ Bianchi, Giuseppe (1844). Documenti per la Storia del Friuli dal 1317 al 1325 (in Latin). p. 706.

- ^ Bizjak, Matjaž; Kosi, Miha; Seručnik, Miha; Šilc, Jurij (2017). Historična topografija Kranjske (do 1500) (in Slovenian). Založba ZRC. p. 269. ISBN 978-961-254-974-9.

- ^ a b Mor, Carlo Guido (1992). I boschi patrimoniali del Patriarcato e di San Marco in Carnia (in Italian and Latin). Cooperativa Alea. pp. 114, 127.

- ^ Gianni, Luca. "Famiglie toscane nel Friuli concordiese: credito e commerci tra Portogruaro e Spilimbergo nel XIV secolo, in I Toscani nel patriarcato di Aquileia in età medievale". (pre-print): 5, 20–22.

- ^ Gianni, Luca. "Alla morte di un abate. La sedevacanza sestense dopo la scomparsa di Ludovico della Frattina (1325- 1347)". (pre-print): 781.

- ^ a b Cagnin, Giampaolo (2000). Pellegrini e vie del pellegrinaggio a Treviso nel Medioevo: secoli XII-XV (in Italian). Vicenza. p. 67. ISBN 978-88-8314-073-0.

- ^ Muratorio, Ludovico Antonio (1774). Antiquitates Italicæ medii ævi (...) (in Latin). Vol. 2. p. 334.

- ^ Atti delle assemblee costituzionali italiane dal Medio Evo al 1831 (in Italian). Zanichelli. 1955. pp. CV.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m De Cicco, Rosa (2010). Pergamene Montereale – Mantica (1286-1624) (PDF) (in Italian). Archivio di Stato di Pordenone. pp. 10, 52–54, 59–84, 88–89, 95–98, 103, 105, 107, 111, 115, 118, 120, 122–123, 128, 132 (n. 24, 201, 205–206, 209, 231, 234, 237, 243–247, 253, 255, 259–264, 271, 274–275, 277, 281–283, 286, 288, 293, 295–297, 299, 301–305, 308, 310–312, 314–316, 319–321, 323, 325–330, 334–335, 350–352, 358, 381, 389, 391, 405, 421, 430, 441, 454, 470, 486, 495, 503, 505, 507, 529, 548). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-04-10.

- ^ Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften (1855). Notizenblatt. Beilage zum Archiv für Kunde österreichischer Geschichtsquellen. Fünfter Jahrgang (in German and Latin). p. 173.

- ^ Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften (1854). Notizenblatt. Beilage zum Archiv für Kunde österreichischer Geschichtsquellen. Vierter Jahrgang (in German and Latin). pp. 60, 77, 523.

- ^ Miniati, Enrico. Storia di Gemona nel basso medioevo (PDF) (in Italian). Università degli Studi di Udine. Corso di dottorato di ricerca in storia: Culture e strutture delle aree di frontiera Ciclo XXIV. Tesi di dottorato di ricerca. p. 274. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-12-07.

- ^ de Boateriis, Nicola (1973). Nicola de Boateriis notaio in Famagosta e Venezia (1355-1365) (in Latin). pp. 304, 366.

- ^ Cagnin, Giampaolo (2004). Cittadini e forestieri a Treviso nel Medioevo: (secoli XIII-XIV) (in Italian). Regione del Veneto. p. 56. ISBN 978-88-8314-246-8.

- ^ Annali di Portogruaro. "1351-1375". Portogruaro2000 (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2022-10-04. Retrieved 2023-08-20.

- ^ Pancera, Antonio (1898). Il codice diplomatico di Antonio Panciera da Portogruaro ... (in Italian). A spese della deputazione. p. 14.

- ^ Joppi, Vicenzo. "Documenti Goriziani del Secolo XIV" (PDF). Archeografo Triestino. Nuova Serie. XVI: 62. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-04-04.

- ^ "Rivista di Scienze e Lettere". Forum Iulii. III (I): 348. 1912.

- ^ Società di Minerva (1890). Archeografo Triestino (in Italian). Vol. 16. p. 62.

- ^ "Epistolae et privilegia (Urbanus III)". la.wikisource.org (in Latin). Archived from the original on 2023-07-13. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ "Castello di Meduno". Consorzio per la Salvaguardia dei Castelli Storici del Friuli Venezia Giulia. Archived from the original on 2021-05-07. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ a b "Comune di Meduno: Storia e cultura". Comune di Meduno. Archived from the original on 2022-05-06.

- ^ a b Königlich Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften (1866). Abhandlungen der Historischen Classe (in German and Latin). p. 418.

- ^ a b Härtel, Reinhard (1985). Die älteren Urkunden des Klosters Moggio (bis 1250) (in German and Latin). Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. pp. 83, 146. ISBN 978-3-7001-0721-7.

- ^ Meighörner, Wolfgang; Bitschnau, Martin; Obermair, Hannes (2009). Tiroler Urkundenbuch: Die Urkunden zur Geschichte des Inn-, Eisack- und Pustertals. Abteilung II (in German and Latin). Universitätsverlag Wagner. p. 292. ISBN 978-3-7030-0469-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Pagine Friulane". Pagine Friulane. Periodico Mensile. VII: 2–3, 52–54. 1894.

- ^ di Crollalanza, Giovan Battista (1888). Dizionario Storico-Blasonico delle Famiglie Nobili e Notabili Italiane (in Italian). Boston Public Library. Bologna: A. Forni. p. 122.

- ^ a b c d Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften (1866). Archiv für österreichische Geschichte (in German and Latin). Vol. 36. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 458. ISBN 978-3-7525-4820-4.

- ^ a b "Meduno (PN) – Castello vescovile. Blog". Castelliere (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2022-09-13. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ a b "Meduno (Pn). Il Castello". Carta Archeologica Online del Friuli Venezia Giulia (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2021-10-23. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ a b "Meduno". italiapedia.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2022-09-13. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ Sistema Informativo Unificato per le Soprintendenze Archivistiche (SIUSA). "Comune di Meduno". siusa.archivi.beniculturali.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2023-07-13. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ Valentinelli, Josephi (2022). Diplomatarium Portusnaonense (in Latin). BoD – Books on Demand. p. 53. ISBN 978-3-375-00970-0.

- ^ Nuovo archivio veneto. Periodico storico trimestrale (in Italian). R. Deputazione Veneta di Storia di Patria. 1907. p. 199.

- ^ Furlan, Caterina; Zannier, Italo (1985). Il Duomo di Spilimbergo, 1284-1984 (in Italian). Comune di Spilimbergo. p. 16.

- ^ Archivio Veneto (1889). Nuova Serie. Anno XIX (in Italian). Vol. XXXVII – Parte I. p. 48.

- ^ "Rivista di Scienze e Lettere". Forum Iulii. I (I): 316. 1910.

- ^ Suardo, Paolo Carlo (1671). Specchio Lucidissimo (…) (in Italian and Latin). p. 30.

- ^ Davide, Miriam (2008). Lombardi in Friuli: per la storia delle migrazioni interne nell'Italia del Trecento (in Italian). CERM. p. 62. ISBN 978-88-95368-03-0.

- ^ a b Brunettin, Giordano (2004). Bertrando di Saint-Geniès patriarca di Aquileia (1334-1350) (in Italian). Fondazione Centro italiano di studi sull'alto Medioevo. pp. 266, 914. ISBN 978-88-7988-093-0.

- ^ Deputazione di Storia Patria per il Friuli (1996). Memorie Storiche Cividalesi: Bulletino del R. Museo di Cividale (in Italian). Vol. 76. p. 70.

- ^ Gubertinus (de Novate), Giordano Brunettin (2001). I protocolli della cancelleria patriarcale del 1341 e del 1343 (in Latin). Istituto Pio Paschini. pp. 347, 367. ISBN 978-88-87948-04-2.

- ^ di Tommaso, Supertino; Baseotto, Carla (1997). Spilimbergo medioevale: dal libro di imbreviature del notaio Supertino di Tommaso (1341-1346) (in Italian and Latin). Comune di Spilimbergo, Biblioteca civica. p. 23.

- ^ Memorie Storiche Cividalesi: Bulletino del R. Museo di Cividale (in Italian). Vol. 86. Deputazione di storia patria per il Friuli. 2006. p. 25.

- ^ Freiherr von Czoernig, Karl (1873). Görz, Österreich's Nizza: Das Land Görz und Gradisca (mit Einschluss von Aquileja) (in German). p. 467.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Goi, Paolo (1993). San Marco di Pordenone. I – Storia, Arte, Musica e Literature. II – Vita Religiosa, Restauro, Documenti (in Italian). pp. 520, 639, 685, 747, 753, 762, 773–775, 778, 989–990, 995–956.

- ^ Piloni, Giorgio (1607). Historiae urbium et Regionum Italiae rariores (in Italian and Latin). Vol. LXV. A. Forni. p. 381.

- ^ Santonino, Paolo; Almagià, Roberto (1942). Itinerario di Paolo Santonino in Carintia, Stiria e Carniola negli anni 1485-1487: (Codice Vaticano 3795). 1942-1943 (in Italian and Latin). Biblioteca apostolica vaticana. p. 28.