Manse Hotel

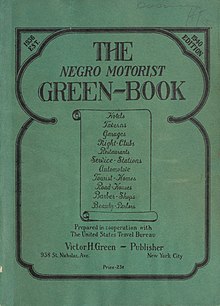

The Manse Hotel is a historic place and former hotel in Walnut Hills, Cincinnati, Ohio which was important to the American civil rights movement. The hotel accommodated African American people (including many celebrities) and events (including local, state, and national civil rights groups meetings) during a time when African Americans were not allowed to stay in other Downtown hotels because of racial segregation.[1] It was listed in The Negro Motorist Green Book from the 1940s through the 1960s[2] and along with the Manse Hotel Annex has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since August 8, 2019.[3][4]

History

[edit]

Originally a Second Empire-style home built c. 1876 and later a rooming house called the Hotel Terry, the property was purchased in 1931 by African American entrepreneur Horace Sudduth.[5] Sudduth was a prominent local businessman — the Cincinnati Enquirer called him "the No. 1 Negro citizen of Cincinnati" in 1951 — who did business in banking and real estate.[6] At first, he made only modest improvements to the facility, and began advertising it as a hotel.[7]

The Hotel Manse was founded in 1937[8] and a nearby building was annexed a few years later.[7] The hotel was listed in The Negro Motorist Green Book, a guide to services and places for African-American roadtrippers during the era of Jim Crow laws, starting in the guide's fourth edition in 1940.[9] The new hotel had major cultural significance for Cincinnati's black community and hosted events including weddings and social and professional group meetings.[4] In one instance in 1943, after black youth were not allowed to stay at the Cincinnati Club, a YMCA Youth conference moved to the Manse where both black and white youth delegates were welcomed.[10] The hotel was the location of the 1946 NAACP National Convention. Notable attendees included future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, boxer Joe Louis and members of the Tuskegee Airmen.[1]

After major renovations, it was renamed the Manse Hotel in 1950. The hotel was expanded to 108 rooms and upgraded with "first-class", modern amenities at the cost of $500,000, which was paid for by Sudduth.[6] The features included circulating ice water in each room, an air-conditioned dining room, and a ballroom with a capacity of 400 guests. His interest was not just in the business opportunity; the Manse Hotel was the most ambitious project of several decades of Sudduth's work to advance civil rights by way of material progress.[7] One of the organizations that met in the hotel was the Cincinnati chapter of Jack and Jill of America. Politician and civil rights activist Marian Spencer attended and was photographed there.[1]

Musicians and entertainers who stayed in the hotel included Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and James Brown. Brown stayed in the hotel many times in the mid-1950s while recording and for a time may have considered it a second home.[4] Hank Ballard wrote "The Twist" in his hotel room at the Manse.[6] Others included Sammy Davis Jr.[7] and Josephine Baker.[11] Visiting black athletes also often stayed in the Manse. These included future Hall of Fame baseball players Frank Robinson, Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Hank Aaron, and Willie Mays.[6] Ezzard Charles, the "Cincinnati Cobra", held a press conference at the hotel when he became the world heavyweight champion in boxing in 1950.[10]

Though the Manse Hotel catered mostly to African Americans, it was fully integrated.[5]

Sudduth died in 1957.[7] The hotel declined after integration made other hotels accessible to black patrons; by the late 1960s it had fallen into disrepair.[8] Sudduth's family sold the property in 1970.[6] It was purchased in 1979 to be converted into low income housing.[7]

The Manse Hotel and Manse Hotel Annex was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 8, 2019.[3][4]

As of 2019, plans were in place for a property developer to convert the property into affordable housing apartments for seniors.[2][12]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Smith, Lisa (1 March 2019). "Manse Hotel and Annex: Local developer bringing historic African-American hotel back to life". WCPO 9 Cincinnati. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ a b Tucker, Randy (26 June 2019). "The former Manse Hotel and onetime 'Green Book' stop lands historic tax credits for senior apartments project". Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ a b "National Register Database and Research". National Park Service. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

Ref# 100004232

- ^ a b c d "Best Historic Preservation Wins: The Manse Hotel and the Mt. Airy Water Towers". CityBeat. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Manse Hotel and Annex, Cincinnati". Ohio Civil Rights Associated Nominations. Ohio History Connection. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Radel, Cliff (21 February 2014). "Walnut Hills hotel served baseball, music superstars". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Middleton, Stephen (Summer 1991). ""We Must Not Fail!!!"*: Horace Sudduth; Queen City Entrepreneur" (PDF). Queen City Heritage: 2–18. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ a b Howard, Allen (2 June 1969). "In Manse's Dusty Ballroom Party's Been Over 20 Years". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Hand, Greg (8 February 2016). "In 1939, Few Cincinnati Businesses Welcomed African-American Travelers". Cincinnati Magazine. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ a b "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Cecilia D. (November 2001). "Chamber Muse". Cincinnati Magazine. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ Smith-Randolph, Walter (28 November 2018). "New life coming to historic Walnut Hills hotel as landmark designation sought". Local12. Retrieved 22 July 2020.