Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman | |

|---|---|

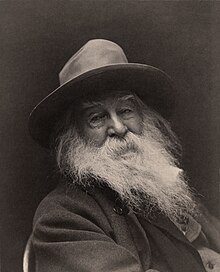

Whitman in 1887 | |

| Born | Walter Whitman Jr. May 31, 1819 Huntington, New York, U.S. |

| Died | March 26, 1892 (aged 72) Camden, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Resting place | Harleigh Cemetery, Camden, New Jersey, U.S. 39°55′38″N 75°05′37″W / 39.9271816°N 75.0937119°W |

| Occupations |

|

| Signature | |

Walter Whitman Jr. (/ˈhwɪtmən/; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist; he also wrote two novels. He is considered one of the most influential poets in American literature. Whitman incorporated both transcendentalism and realism in his writings and is often called the father of free verse.[1] His work was controversial in his time, particularly his 1855 poetry collection Leaves of Grass, which was described by some as obscene for its overt sensuality.

Whitman was born in Huntington on Long Island and lived in Brooklyn as a child and through much of his career. At age 11, he left formal schooling to go to work. He worked as a journalist, a teacher, and a government clerk. Whitman's major poetry collection, Leaves of Grass, first published in 1855, was financed with his own money and became well known. The work was an attempt to reach out to the common person with an American epic. Whitman continued expanding and revising Leaves of Grass until his death in 1892.

During the American Civil War, he went to Washington, D.C., and worked in hospitals caring for the wounded. His poetry often focused on both loss and healing. On the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, whom Whitman greatly admired, he authored two poems, "O Captain! My Captain!" and "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd", and gave a series of lectures on Lincoln. After suffering a stroke towards the end of his life, Whitman moved to Camden, New Jersey, where his health further declined. When he died at age 72, his funeral was a public event.[2][3]

Whitman's influence on poetry remains strong. Art historian Mary Berenson wrote, "You cannot really understand America without Walt Whitman, without Leaves of Grass... He has expressed that civilization, 'up to date,' as he would say, and no student of the philosophy of history can do without him."[4] Modernist poet Ezra Pound called Whitman "America's poet... He is America."[5] According to the Poetry Foundation, he is "America's world poet—a latter-day successor to Homer, Virgil, Dante, and Shakespeare."[6]

Life and work

[edit]Early life

[edit]

Whitman was born on May 31, 1819, in West Hills, New York, the second of nine children of Quaker parents Walter and Louisa Van Velsor Whitman,[7] of English and Dutch descent respectively.[8] He was immediately nicknamed "Walt" to distinguish him from his father.[9] At the age of four, Whitman moved with his family from Huntington to Brooklyn, living in a series of homes, in part due to bad investments.[10] Whitman looked back on his childhood as generally restless and unhappy, given his family's difficult economic struggles.[11] One happy moment that he later recalled was when he was lifted in the air and kissed on the cheek by the Marquis de Lafayette during a celebration of the setting of the Brooklyn Apprentices' Library's cornerstone by Lafayette in Brooklyn on July 4, 1825.[12] Whitman later worked as a librarian at that institution.[13]

At the age of 11, Whitman ended his formal schooling[14] and sought employment to assist his family, which was struggling economically. He was an office boy for two lawyers and later was an apprentice and printer's devil for the weekly Long Island newspaper the Patriot, edited by Samuel E. Clements.[15] There, Whitman learned about the printing press and typesetting.[16] He may have written "sentimental bits" of filler material for occasional issues.[17] Clements aroused controversy when he and two friends attempted to dig up the corpse of the Quaker minister Elias Hicks to create a plaster mold of his head.[18] Clements left the Patriot shortly afterward, possibly as a result of the controversy.[19]

Career

[edit]

The following summer Whitman worked for another printer, Erastus Worthington, in Brooklyn.[20] His family moved back to West Hills, New York, on Long Island in the spring, but Whitman remained and took a job at the shop of Alden Spooner, editor of the leading Whig weekly newspaper the Long-Island Star.[20] While at the Star, Whitman became a regular patron of the local library, joined a town debating society, began attending theater performances,[21] and anonymously published some of his earliest poetry in the New-York Mirror.[22] At the age of 16 in May 1835, Whitman left the Star and Brooklyn.[23] He moved to New York City to work as a compositor[24] though, in later years, Whitman could not remember where.[25] He attempted to find further work but had difficulty, in part due to a severe fire in the printing and publishing district,[25] and in part due to a general collapse in the economy leading up to the Panic of 1837.[26] In May 1836, he rejoined his family, now living in Hempstead, Long Island.[27] Whitman taught intermittently at various schools until the spring of 1838, though he was not satisfied as a teacher.[28]

After his teaching attempts, Whitman returned to Huntington, New York, to found his own newspaper, the Long-Islander. Whitman served as publisher, editor, pressman, and distributor and even provided home delivery. After ten months, he sold the publication to E. O. Crowell, whose first issue appeared on July 12, 1839.[29] There are no known surviving copies of the Long-Islander published under Whitman.[30] By the summer of 1839, he found a job as a typesetter in Jamaica, Queens, with the Long Island Democrat, edited by James J. Brenton.[29] He left shortly thereafter, and made another attempt at teaching from the winter of 1840 to the spring of 1841.[31] One story, possibly apocryphal, tells of Whitman's being chased away from a teaching job in Southold, New York, in 1840. After a local preacher called him a "Sodomite", Whitman was allegedly tarred and feathered. Biographer Justin Kaplan notes that the story is likely untrue, because Whitman regularly vacationed in the town thereafter.[32] Biographer Jerome Loving calls the incident a "myth".[33] During this time, Whitman published a series of ten editorials, called "Sun-Down Papers—From the Desk of a Schoolmaster", in three newspapers between the winter of 1840 and July 1841. In these essays, he adopted a constructed persona, a technique he would employ throughout his career.[34]

Whitman moved to New York City in May, initially working a low-level job at the New World, working under Park Benjamin Sr. and Rufus Wilmot Griswold.[35] He continued working for short periods of time for various newspapers; in 1842 he was editor of the Aurora and from 1846 to 1848 he was editor of the Brooklyn Eagle.[36] While working for the latter institution, many of his publications were in the area of music criticism, and it is during this time that he became a devoted lover of Italian opera through reviewing performances of works by Bellini, Donizetti, and Verdi. This new interest had an impact on his writing in free verse. He later said, "But for the opera, I could never have written Leaves of Grass."[37]

Throughout the 1840s, Whitman contributed freelance fiction and poetry to various periodicals,[38] including Brother Jonathan magazine edited by John Neal.[39] Whitman lost his position at the Brooklyn Eagle in 1848 after siding with the free-soil "Barnburner" wing of the Democratic party against the newspaper's owner, Isaac Van Anden, who belonged to the conservative, or "Hunker", wing of the party.[40] Whitman was a delegate to the 1848 founding convention of the Free Soil Party, which was concerned about the threat slavery would pose to free white labor and northern businessmen moving into the newly colonized western territories. Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison derided the party philosophy as "white manism".[41]

In 1852, he serialized a novel, Life and Adventures of Jack Engle, in six installments of New York's The Sunday Dispatch.[42] In 1858, Whitman published a 47,000 word series, Manly Health and Training, under the pen name Mose Velsor.[43][44] Apparently he drew the name Velsor from Van Velsor, his mother's family name.[45] This self-help guide recommends beards, nude sunbathing, comfortable shoes, bathing daily in cold water, eating meat almost exclusively, plenty of fresh air, and getting up early each morning. Present-day writers have called Manly Health and Training "quirky",[46] "so over the top",[47] "a pseudoscientific tract",[48] and "wacky".[43]

Leaves of Grass

[edit]

Whitman claimed that after years of competing for "the usual rewards", he determined to become a poet.[49] He first experimented with a variety of popular literary genres that appealed to the cultural tastes of the period.[50] As early as 1850, he began writing what would become Leaves of Grass,[51] a collection of poetry that he would continue editing and revising until his death.[52] Whitman intended to write a distinctly American epic[53] and used free verse with a cadence based on the Bible.[54] At the end of June 1855, Whitman surprised his brothers with the already-printed first edition of Leaves of Grass. George "didn't think it worth reading".[55]

Whitman paid for the publication of the first edition of Leaves of Grass himself[55] and had it printed at a local print shop during its employees' breaks from commercial jobs.[56] A total of 795 copies were printed.[57] No author is named; instead, facing the title page was an engraved portrait done by Samuel Hollyer,[58] but 500 lines into the body of the text he calls himself "Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos, disorderly, fleshly, and sensual, no sentimentalist, no stander above men or women or apart from them, no more modest than immodest".[59] The inaugural volume of poetry was preceded by a prose preface of 827 lines. The succeeding untitled twelve poems totaled 2315 lines with 1336 lines belonging to the first untitled poem, later called "Song of Myself". The book received its strongest praise from Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote a flattering five-page letter to Whitman and spoke highly of the book to friends.[60] Emerson called it "the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed."[6] Emerson had called for the first truly American poet, saying that aspects of America "are yet unsung. Yet America is a poem in our eyes."[61]

The first edition of Leaves of Grass was widely distributed and stirred up significant interest,[62] in part due to Emerson's praise,[63] but was occasionally criticized for the seemingly "obscene" nature of the poetry.[64] Geologist Peter Lesley wrote to Emerson, calling the book "trashy, profane & obscene" and the author "a pretentious ass".[65] Whitman embossed a quote from Emerson's letter, "I greet you at the beginning of a great career", in gold leaf on the spine of the second edition. Of this action, Laura Dassow Walls, professor emerita of English at the University of Notre Dame,[66] wrote: "In one stroke, Whitman had given birth to the modern cover blurb, quite without Emerson's permission."[67]

On July 11, 1855, a few days after Leaves of Grass was published, Whitman's father died at the age of 65.[68] In the months following the first edition of Leaves of Grass, critical responses began focusing on what some found offensive sexual themes. Though the second edition was already printed and bound, the publisher almost did not release it.[69] In the end, the edition went to retail, with 20 additional poems,[70] in August 1856.[71] Leaves of Grass was revised and re-released in 1860,[72] again in 1867, and several more times throughout the remainder of Whitman's life. Several well-known writers admired the work enough to visit Whitman, including Amos Bronson Alcott and Henry David Thoreau.[73]

During the first publications of Leaves of Grass, Whitman had financial difficulties and was forced to work as a journalist again, specifically with Brooklyn's Daily Times starting in May 1857.[74] As an editor, he oversaw the paper's contents, contributed book reviews, and wrote editorials.[75] He left the job in 1859, though it is unclear whether he was fired or chose to leave.[76] Whitman, who typically kept detailed notebooks and journals, left very little information about himself in the late 1850s.[77]

Civil War years

[edit]

As the American Civil War was beginning, Whitman published his poem "Beat! Beat! Drums!" as a patriotic rally call for the Union.[78] Whitman's brother George had joined the Union army in the 51st New York Infantry Regiment and began sending Whitman several vividly detailed letters of the battle front.[79] On December 16, 1862, a listing of fallen and wounded soldiers in the New-York Tribune included "First Lieutenant G. W. Whitmore", which Whitman worried was a reference to his brother George.[80] He made his way south immediately to find him, though his wallet was stolen on the way.[81] "Walking all day and night, unable to ride, trying to get information, trying to get access to big people", Whitman later wrote,[82] he eventually found George alive, with only a superficial wound on his cheek.[80] Whitman, profoundly affected by seeing the wounded soldiers and the heaps of their amputated limbs, left for Washington, D.C., on December 28, 1862, with the intention of never returning to New York.[81]

In Washington, D.C., Whitman's friend Charley Eldridge helped him obtain part-time work in the army paymaster's office, leaving time for Whitman to volunteer as a nurse in the army hospitals.[83] He would write of this experience in "The Great Army of the Sick", published in a New York newspaper in 1863[84] and, 12 years later, in a book called Memoranda During the War.[85] He then contacted Emerson, this time to ask for help in obtaining a government post.[81] Another friend, John Trowbridge, passed on a letter of recommendation from Emerson to Salmon P. Chase, Secretary of the Treasury, hoping he would grant Whitman a position in that department. Chase, however, did not want to hire the author of such a disreputable book as Leaves of Grass.[86]

The Whitman family had a difficult end to 1864. On September 30, 1864, Whitman's brother George was captured by Confederate forces in Virginia,[87] and another brother, Andrew Jackson, died of tuberculosis compounded by alcoholism on December 3.[88] That month, Whitman committed his brother Jesse to the Kings County Lunatic Asylum.[89] Whitman's spirits were raised, however, when he finally got a better-paying government post as a low-grade clerk in the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the Department of the Interior, thanks to his friend William Douglas O'Connor. O'Connor, a poet, daguerreotypist, and an editor at The Saturday Evening Post wrote to William Tod Otto, Assistant Secretary of the Interior, on Whitman's behalf.[90] Whitman began the new appointment on January 24, 1865, with a yearly salary of $1,200.[91] A month later, on February 24, 1865, George was released from capture and granted a furlough because of his poor health.[90] By May 1, Whitman received a promotion to a slightly higher clerkship[91] and published Drum-Taps.[92]

Effective June 30, 1865, however, Whitman was fired from his job.[92] His dismissal came from the new Secretary of the Interior, former Iowa Senator James Harlan.[91] Though Harlan dismissed several clerks who "were seldom at their respective desks", he may have fired Whitman on moral grounds after finding an 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass.[93] O'Connor protested until J. Hubley Ashton had Whitman transferred to the Attorney General's office on July 1.[94] O'Connor, though, was still upset and vindicated Whitman by publishing a biased and exaggerated biographical study, The Good Gray Poet, in January 1866.[95] The fifty-cent pamphlet defended Whitman as a wholesome patriot, established the poet's nickname and increased his popularity.[96] Also aiding in his popularity was the publication of "O Captain! My Captain!", a conventional poem on the death of Abraham Lincoln, the only poem to appear in anthologies during Whitman's lifetime.[97]

Part of Whitman's role at the Attorney General's office was interviewing former Confederate soldiers for presidential pardons. "There are real characters among them", he later wrote, "and you know I have a fancy for anything out of the ordinary."[98] In August 1866, he took a month off to prepare a new edition of Leaves of Grass which would not be published until 1867 after difficulty in finding a publisher.[99] He hoped it would be its last edition.[100] In February 1868, Poems of Walt Whitman was published in England thanks to the influence of William Michael Rossetti,[101] with minor changes that Whitman reluctantly approved.[102] The edition became popular in England, especially with endorsements from the highly respected writer Anne Gilchrist.[103] Another edition of Leaves of Grass was issued in 1871, the same year it was mistakenly reported that its author died in a railroad accident.[104] As Whitman's international fame increased, he remained at the attorney general's office until January 1872.[105] He spent much of 1872 caring for his mother, who was now nearly eighty and struggling with arthritis.[106] He also traveled and was invited to Dartmouth College to give the commencement address on June 26, 1872.[107]

Health decline and death

[edit]

After suffering a paralytic stroke in early 1873, Whitman was induced to move from Washington to the home of his brother—George Washington Whitman, an engineer—at 431 Stevens Street in Camden, New Jersey. His mother, having fallen ill, was also there and died that same year in May. Both events were difficult for Whitman and left him depressed. He remained at his brother's home until buying his own in 1884.[108] However, before purchasing his home, he spent the greatest period of his residence in Camden at his brother's home on Stevens Street. While in residence there he was very productive, publishing three versions of Leaves of Grass among other works. He was also last fully physically active in this house, receiving both Oscar Wilde and Thomas Eakins. His other brother, Edward, an "invalid" since birth, lived in the house.[109]

When his brother and sister-in-law were forced to move for business reasons, he bought his own house at 328 Mickle Street (now 330 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard).[110] First taken care of by tenants, he was completely bedridden for most of his time in Mickle Street. During this time, he began socializing with Mary Oakes Davis—the widow of a sea captain. She was a neighbor, boarding with a family in Bridge Avenue just a few blocks from Mickle Street.[111] She moved in with Whitman on February 24, 1885, to serve as his housekeeper in exchange for free rent. She brought with her a cat, a dog, two turtledoves, a canary, and other assorted animals.[112] During this time, Whitman produced further editions of Leaves of Grass in 1876, 1881, and 1889.[109]

While in South Jersey, Whitman spent a good portion of his time in the then quite pastoral community of Laurel Springs, between 1876 and 1884, converting one of the Stafford Farm buildings to his summer home. The restored summer home has been preserved as a museum by the local historical society. Part of his Leaves of Grass was written here, and in his Specimen Days he wrote of the spring, creek and lake. To him, Laurel Lake was "the prettiest lake in: either America or Europe".[113]

As the end of 1891 approached, he prepared a final edition of Leaves of Grass, a version that has been nicknamed the "Deathbed Edition". He wrote, "L. of G. at last complete—after 33 y'rs of hackling at it, all times & moods of my life, fair weather & foul, all parts of the land, and peace & war, young & old."[114] Preparing for death, Whitman commissioned a granite mausoleum shaped like a house for $4,000[115] and visited it often during construction.[116] In the last week of his life, he was too weak to lift a knife or fork and wrote: "I suffer all the time: I have no relief, no escape: it is monotony—monotony—monotony—in pain."[117]

Walt Whitman died on March 26, 1892,[118] at his home in Camden, New Jersey at the age of 72.[119] An autopsy revealed his lungs had diminished to one-eighth their normal breathing capacity, a result of bronchial pneumonia,[115] and that an egg-sized abscess on his chest had eroded one of his ribs. The cause of death was officially listed as "pleurisy of the left side, consumption of the right lung, general miliary tuberculosis and parenchymatous nephritis".[120] A public viewing of his body was held at his Camden home; more than 1,000 people visited in three hours.[2] Whitman's oak coffin was barely visible because of all the flowers and wreaths left for him.[120] Four days after his death, he was buried in his tomb at Harleigh Cemetery in Camden.[2] Another public ceremony was held at the cemetery, with friends giving speeches, live music, and refreshments.[3] Whitman's friend, the orator Robert Ingersoll, delivered the eulogy.[121] Later, the remains of Whitman's parents and two of his brothers and their families were moved to the mausoleum.[122] His brain was donated to the American Anthropometric Society in Philadelphia, but it was accidentally destroyed.[123]

Writing

[edit]

Whitman's work broke the boundaries of poetic form and is generally prose-like.[1] Its signature style deviates from the course set by his predecessors and includes "idiosyncratic treatment of the body and the soul as well as of the self and the other."[124] It uses unusual images and symbols, including rotting leaves, tufts of straw, and debris.[125] Whitman openly wrote about death and sexuality, including prostitution.[100] He is often labeled the father of free verse, though he did not invent it.[1]

Poetic theory

[edit]Whitman wrote in the preface to the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass: "The proof of a poet is that his country absorbs him as affectionately as he has absorbed it." He believed there was a vital, symbiotic relationship between the poet and society.[126] He emphasized this connection especially in "Song of Myself" by using an all-powerful first-person narration.[127] An American epic, it deviated from the historic use of an elevated hero and instead assumed the identity of the common people.[128] Leaves of Grass also responded to the impact of rapid urbanization in the United States on the masses.[129]

Lifestyle and beliefs

[edit]Alcohol

[edit]Whitman was a vocal proponent of temperance and in his youth rarely drank alcohol. He once stated he did not taste "strong liquor" until he was 30[130] and occasionally argued for prohibition.[131] His first novel, Franklin Evans, or The Inebriate, published November 23, 1842, is a temperance novel.[132] Whitman wrote the novel at the height of the popularity of the Washingtonian movement, a movement that was plagued with contradictions, as was Franklin Evans.[133] Years later Whitman claimed he was embarrassed by the book[134] and called it "damned rot".[135] He dismissed it by saying he wrote the novel in three days solely for money while under the influence of alcohol.[136] Even so, he wrote other pieces recommending temperance, including The Madman and a short story "Reuben's Last Wish".[137] Later in life he was more liberal with alcohol, enjoying local wines and champagne.[138]

Religion

[edit]Whitman was deeply influenced by deism. He denied any one faith was more important than another, and embraced all religions equally.[139] In "Song of Myself", he gave an inventory of major religions and indicated he respected and accepted all of them—a sentiment he further emphasized in his poem "With Antecedents", affirming: "I adopt each theory, myth, god, and demi-god, / I see that the old accounts, bibles, genealogies, are true, without exception".[139] In 1874, he was invited to write a poem about the Spiritualism movement, to which he responded: "It seems to me nearly altogether a poor, cheap, crude humbug."[140] Whitman was a religious skeptic: though he accepted all churches, he believed in none.[139] God, to Whitman, was both immanent and transcendent and the human soul was immortal and in a state of progressive development.[141] American Philosophy: An Encyclopedia classes him as one of several figures who "took a more pantheist or pandeist approach by rejecting views of God as separate from the world."[142]

Sexuality

[edit]

Though biographers continue to debate Whitman's sexuality, he is usually described as either homosexual or bisexual in his feelings and attractions. Whitman's sexual orientation is generally assumed on the basis of his poetry, though this assumption has been disputed. His poetry depicts love and sexuality in a more earthy, individualistic way common in American culture before the medicalization of sexuality in the late 19th century.[143][144] Though Leaves of Grass was often labeled pornographic or obscene, only one critic remarked on its author's presumed sexual activity: in a November 1855 review, Rufus Wilmot Griswold suggested Whitman was guilty of "that horrible sin not to be mentioned among Christians".[145] The manuscript of his love poem "Once I Pass'd Through A Populous City", written when Whitman was 29, indicates it was originally about a man.[146] Late in his life, when Whitman was asked outright whether his "Calamus" poems were homosexual—John Addington Symonds inquired about "athletic friendship", "the love of man for man", or "the Love of Friends"[147]—he chose not to respond.[148][149]

Whitman had intense friendships with many men and boys throughout his life. Some biographers have suggested that he did not actually engage in sexual relationships with males,[150] while others cite letters, journal entries, and other sources that they claim as proof of the sexual nature of some of his relationships.[151] English poet and critic John Addington Symonds spent 20 years in correspondence trying to pry the answer from him.[152] In 1890, Symonds wrote to Whitman: "In your conception of Comradeship, do you contemplate the possible intrusion of those semi-sexual emotions and actions which no doubt do occur between men?" In reply, Whitman denied that his work had any such implication, asserting "[T]hat the calamus part has even allow'd the possibility of such construction as mention'd is terrible—I am fain to hope the pages themselves are not to be even mention'd for such gratuitous and quite at this time entirely undream'd & unreck'd possibility of morbid inferences—wh' are disavow'd by me and seem damnable", and insisting that he had fathered six illegitimate children. Some contemporary scholars are skeptical of the veracity of Whitman's denial or the existence of the children he claimed.[153][154][155][156] In a letter dated August 21, 1890, Whitman claimed: "I have had six children—two are dead." This claim has never been corroborated.[157]

Peter Doyle may be the most likely candidate for the love of Whitman's life.[158][159][160] Doyle was a bus conductor whom Whitman met around 1866, and the two were inseparable for several years. Interviewed in 1895, Doyle said: "We were familiar at once—I put my hand on his knee—we understood. He did not get out at the end of the trip—in fact went all the way back with me."[161] In his notebooks, Whitman disguised Doyle's initials using the code "16.4" (P.D. being the 16th and 4th letters of the alphabet).[159] Oscar Wilde met Whitman in the United States in 1882 and later told the homosexual-rights activist George Cecil Ives that "I have the kiss of Walt Whitman still on my lips."[162] The only explicit description of Whitman's sexual activities is secondhand. In 1924, Edward Carpenter told Gavin Arthur of a sexual encounter in his youth with Whitman, the details of which Arthur recorded in his journal.[163][164][165]

Another possible lover was Bill Duckett. As a teenager, he lived on the same street in Camden and moved in with Whitman, living with him a number of years and serving him in various roles. Duckett was 15 when Whitman bought his house at 328 Mickle Street. From at least 1880, Duckett and his grandmother, Lydia Watson, were boarders, subletting space from another family at 334 Mickle Street. Because of this proximity, Duckett and Whitman met as neighbors. Their relationship was close, with the youth sharing Whitman's money when he had it. Whitman described their friendship as "thick". Though some biographers describe Duckett as a boarder, others identify him as a lover.[166] Their photograph together is described as "modeled on the conventions of a marriage portrait", part of a series of portraits of the poet with his young male friends, and encrypting male–male desire.[167] Another young man with whom Whitman had an intense relationship was Harry Stafford, with whose family Whitman stayed when at Timber Creek, and whom he first met in 1876, when Stafford was 18. Whitman gave Stafford a ring, which was returned and re-given over the course of a stormy relationship lasting several years. Of that ring, Stafford wrote to Whitman: "You know when you put it on there was but one thing to part it from me, and that was death."[168]

There is also some evidence that Whitman had sexual relationships with women. He had a romantic friendship with a New York actress, Ellen Grey, in the spring of 1862, but it is not known whether it was also sexual. He still had a photograph of her decades later, when he moved to Camden, and he called her "an old sweetheart of mine".[169] Toward the end of his life, he often told stories of previous girlfriends and sweethearts and denied an allegation from the New York Herald that he had "never had a love affair".[170] As Whitman biographer Jerome Loving wrote, "the discussion of Whitman's sexual orientation will probably continue in spite of whatever evidence emerges."[150]

Shakespeare authorship

[edit]Whitman was an adherent of the Shakespeare authorship question, refusing to believe in the historical attribution of the works to William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon. In 1888, Whitman commented in November Boughs:

Conceiv'd out of the fullest heat and pulse of European feudalism—personifying in unparalleled ways the medieval aristocracy, its towering spirit of ruthless and gigantic caste, with its own peculiar air and arrogance (no mere imitation)—only one of the "wolfish earls" so plenteous in the plays themselves, or some born descendant and knower, might seem to be the true author of those amazing works—works in some respects greater than anything else in recorded literature.[171]

Slavery

[edit]Like many in the Free Soil Party who were concerned about the threat slavery would pose to free white labor and northern businessmen exploiting the newly colonized western territories,[172] Whitman opposed the extension of slavery in the United States and supported the Wilmot Proviso.[173] At first he was opposed to abolitionism, believing the movement did more harm than good. In 1846, he wrote that the abolitionists had, in fact, slowed the advancement of their cause by their "ultraism and officiousness".[174] His main concern was that their methods disrupted the democratic process, as did the refusal of the Southern states to put the interests of the nation as a whole above their own.[173] In 1856, in his unpublished The Eighteenth Presidency, addressing the men of the South, he wrote "you are either to abolish slavery or it will abolish you". Whitman also subscribed to the widespread opinion that even free African-Americans should not vote[175] and was concerned at the increasing number of African-Americans in the legislature; as David Reynolds notes, Whitman wrote in prejudiced terms of these new voters and politicians, calling them "blacks, with about as much intellect and calibre (in the mass) as so many baboons."[176] George Hutchinson and David Drews have written that "what little is known about the early development of Whitman's racial awareness suggests that he imbibed the prevailing white prejudices of his time and place, thinking of black people as servile, shiftless, ignorant, and given to stealing," but that despite his views remaining largely unchanged, "readers of the twentieth century, including black ones, imagined him as a fervent antiracist."[177]

Nationalism

[edit]Whitman is often described as America's national poet, creating an image of the United States for itself. "Although he is often considered a champion of democracy and equality, Whitman constructs a hierarchy with himself at the head, America below, and the rest of the world in a subordinate position."[178] In his study "The Pragmatic Whitman: Reimagining American Democracy", Stephen John Mack suggests that critics, who tend to ignore it, should look again at Whitman's nationalism: "Whitman's seemingly mawkish celebrations of the United States [...] [are] one of those problematic features of his works that teachers and critics read past or explain away" (xv–xvi). Nathanael O'Reilly in an essay on "Walt Whitman's Nationalism in the First Edition of Leaves of Grass" claims that "Whitman's imagined America is arrogant, expansionist, hierarchical, racist and exclusive; such an America is unacceptable to Native Americans, African-Americans, immigrants, the disabled, the infertile, and all those who value equal rights."[178] Whitman's nationalism avoided issues concerning the treatment of Native Americans. As George Hutchinson and David Drews further suggest in an essay "Racial attitudes": "Clearly, Whitman could not consistently reconcile the ingrained, even foundational, racist character of the United States with its egalitarian ideals. He could not even reconcile such contradictions in his own psyche." The authors concluded their essay with:[177]

Because of the radically democratic and egalitarian aspects of his poetry, readers generally expect, and desire for, Whitman to be among the literary heroes that transcended the racist pressures that abounded in all spheres of public discourse during the nineteenth century. He did not, at least not consistently; nonetheless his poetry has been a model for democratic poets of all nations and races, right up to our own day. How Whitman could have been so prejudiced, and yet so effective in conveying an egalitarian and antiracist sensibility in his poetry, is a puzzle yet to be adequately addressed.

In reference to the Mexican–American War, Whitman wrote in 1864 that Mexico was "the only [country] to whom we have ever really done wrong."[179] In 1883, celebrating the 333rd anniversary of Santa Fe, Whitman argued that the indigenous and Spanish-Indian elements would supply leading traits in the "composite American identity of the future."[180]

As to our aboriginal or Indian population—the Aztec in the South, and many a tribe in the North and West—I know it seems to be agreed that they must gradually dwindle as time rolls on, and in a few generations more leave only a reminiscence, a blank. But I am not at all clear about that. As America, from its many far-back sources and current supplies, develops, adapts, entwines, faithfully identifies its own—are we to see it cheerfully accepting and using all the contributions of foreign lands from the whole outside globe—and then rejecting the only ones distinctively its own—the autochthonic ones? As to the Spanish stock of our Southwest, it is certain to me that we do not begin to appreciate the splendor and sterling value of its race element. Who knows but that element, like the course of some subterranean river, dipping invisibly for a hundred or two years, is now to emerge in broadest flow and permanent action?[181]

Legacy and influence

[edit]

Whitman has been claimed as the first "poet of democracy" in the United States, a title meant to reflect his ability to write in a singularly American character. An American-British friend of Whitman, Mary Whitall Smith Costelloe, wrote: "You cannot really understand America without Walt Whitman, without Leaves of Grass ... He has expressed that civilization, 'up to date,' as he would say, and no student of the philosophy of history can do without him."[4] Andrew Carnegie called him "the great poet of America so far".[182] Whitman considered himself a messiah-like figure in poetry.[183] Others agreed: one of his admirers, William Sloane Kennedy, speculated that "people will be celebrating the birth of Walt Whitman as they are now the birth of Christ".[184]

Literary critic Harold Bloom wrote, as the introduction for the 150th anniversary of Leaves of Grass:

If you are American, then Walt Whitman is your imaginative father and mother, even if, like myself, you have never composed a line of verse. You can nominate a fair number of literary works as candidates for the secular Scripture of the United States. They might include Melville's Moby-Dick, Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and Emerson's two series of Essays and The Conduct of Life. None of those, not even Emerson's, are as central as the first edition of Leaves of Grass.[185]

In his own time, Whitman attracted an influential coterie of disciples and admirers. Among his admirers were the Eagle Street College, an informal group established in 1885 at the home of James William Wallace on Eagle Street in Bolton, England, to read and discuss the poetry of Whitman. The group subsequently became known as the Bolton Whitman Fellowship or Whitmanites. Its members held an annual "Whitman Day" celebration around the poet's birthday.[186]

American poets

[edit]Whitman is one of the most influential American poets. Modernist poet Ezra Pound called Whitman "America's poet ... He is America."[5] To poet Langston Hughes, who wrote "I, too, sing America", Whitman was a literary hero.[187] Whitman's vagabond lifestyle was adopted by the Beat movement and its leaders such as Allen Ginsberg[188] and Jack Kerouac in the 1950s and 1960s, as well as anti-war poets such as Adrienne Rich, Alicia Ostriker, and Gary Snyder.[189] Lawrence Ferlinghetti numbered himself among Whitman's "wild children", and the title of Ferlinghetti's 1961 collection Starting from San Francisco is a reference to Whitman's Starting from Paumanok.[190] June Jordan published a pivotal essay entitled "For the Sake of People's Poetry: Walt Whitman and the Rest of Us", praising Whitman as a democratic poet whose works speak to ethnic minorities from all backgrounds.[191] United States poet laureate Joy Harjo, who is a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, counts Whitman among her influences.[192]

Latin American poets

[edit]Whitman's poetry influenced Latin American and Caribbean poets in the 19th and 20th centuries, starting with Cuban poet, philosopher, and nationalist leader José Martí, who published essays in Spanish on Whitman's writings in 1887.[193][194][195] Álvaro Armando Vasseur's 1912 translations further raised Whitman's profile in Latin America.[196] Peruvian vanguardist César Vallejo, Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, and Argentine Jorge Luis Borges acknowledged Walt Whitman's influence.[196]

European authors

[edit]Some, like Oscar Wilde and Edward Carpenter, viewed Whitman both as a prophet of a utopian future and of same-sex desire—the passion of comrades. This aligned with their own desires for a future of brotherly socialism.[197] Whitman also influenced Bram Stoker, author of Dracula, and was a model for the character of Dracula. Stoker said in his notes that Dracula represented the quintessential male which, to Stoker, was Whitman, with whom he corresponded until Whitman's death.[198]

Film and television

[edit]Whitman's life and verse have been referenced in a substantial number of works of film and video. In the movie Beautiful Dreamers (Hemdale Films, 1992) Whitman was portrayed by Rip Torn. Whitman visits an insane asylum in London, Ontario, where some of his ideas are adopted as part of an occupational therapy program.[199]

In Dead Poets Society (1989) by Peter Weir, teacher John Keating inspires his students with the works of Whitman, Shakespeare and John Keats.[199][200]

Whitman's poem "Yonnondio" influenced both a book (Yonnondio: From the Thirties, 1974) by Tillie Olsen and a sixteen-minute film, Yonnondio (1994) by Ali Mohamed Selim.[199]

Whitman's poem "I Sing the Body Electric" (1855) was used by Ray Bradbury as the title of a short story and a short story collection. Bradbury's story was adapted for the Twilight Zone episode of May 18, 1962, in which a bereaved family buys a made-to-order robot grandmother to forever love and serve the family.[201] "I Sing the Body Electric" inspired the showcase finale in the movie Fame (1980), a diverse fusion of gospel, rock, and orchestra.[199][202]

Music and audio recordings

[edit]Whitman's poetry has been set to music by more than 500 composers; indeed it has been suggested that his poetry has been set to music more than that of any other American poet except for Emily Dickinson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.[203][204] Those who have set his poems to music include John Adams; Ernst Bacon; Leonard Bernstein; Benjamin Britten; Rhoda Coghill; David Conte; Ronald Corp; George Crumb; Frederick Delius; Howard Hanson; Karl Amadeus Hartmann; Hans Werner Henze; Bernard Herrmann;[205]Jennifer Higdon;[206] Paul Hindemith;[207] Ned Rorem;[208] Howard Skempton; Eva Ruth Spalding; Williametta Spencer; Charles Villiers Stanford; Robert Strassburg;[209] Ananda Sukarlan; Ivana Marburger Themmen;[210] Rossini Vrionides;[211] Ralph Vaughan Williams;[212] Kurt Weill;[213] Helen L. Weiss;[214] Charles Wood; and Roger Sessions.[215] Crossing, an opera composed by Matthew Aucoin and inspired by Whitman's Civil War diaries, premiered in 2015.[216]

In 2014, German publisher Hörbuch Hamburg issued the bilingual double-CD audio book of the Kinder Adams/Children of Adam cycle, based on translations by Kai Grehn in the 2005 Children of Adam from Leaves of Grass (Galerie Vevais), accompanying a collection of nude photography by Paul Cava. The audio release included a complete reading by Iggy Pop, as well as readings by Marianne Sägebrecht; Martin Wuttke; Birgit Minichmayr; Alexander Fehling; Lars Rudolph; Volker Bruch; Paula Beer; Josef Osterndorf; Ronald Lippok; Jule Böwe; and Robert Gwisdek.[217][218] In 2014 composer John Zorn released On Leaves of Grass, an album inspired by and dedicated to Whitman.[219]

Namesake recognition

[edit]Whitman's importance in American culture is reflected in schools, roads, rest stops, and bridges named after him. Among them are the Walt Whitman High School in Bethesda, Maryland and Walt Whitman High School on Long Island, Walt Whitman Elementary School (Woodbury, New York), Walt Whitman Boulevard (Cherry Hill, New Jersey), and a service area on the New Jersey Turnpike in Cherry Hill, to name a few.[citation needed]

The Walt Whitman Bridge, which crosses the Delaware River between Philadelphia and Gloucester City, New Jersey near Whitman's home in Camden, New Jersey, was opened on May 16, 1957.[220] A statue of Whitman by Jo Davidson is located at the entrance to the Walt Whitman Bridge and another casting resides in the Bear Mountain State Park. The controversy that surrounded the naming of the Walt Whitman bridge has been documented in a series of letters from members of the public, which are held in the University of Pennsylvania library.[221] The web page about this matter states: "The bridge was meant to be named after a person of note who had lived in New Jersey, but some area citizens opposed the name 'Walt Whitman Bridge'.... Many objecting to the choice of his name for the bridge saw Whitman's work as sympathizing with communist ideals and criticized him for his egalitarian view of humanity."[221]

In 1997, the Walt Whitman Community School in Dallas opened, becoming the first private high school catering to LGBT youth.[222] His other namesakes include the Walt Whitman Shops in Huntington Station, New York, near his birthplace, and Walt Whitman Road, which spans Huntington Station to Melville on Long Island.[223]

Whitman was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame in 2009,[224] and, in 2013, he was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display that celebrates LGBT history and people.[225]

A coed summer camp founded in 1948 in Piermont, New Hampshire, is named after Whitman.[226][227]

A crater on Mercury is named for him.[228]

Works

[edit]- Franklin Evans; or The Inebriate: A Tale of the Times (1842)

- The Half-Breed; A Tale of the Western Frontier (1846)

- Life and Adventures of Jack Engle (serialized in 1852)[42]

- Leaves of Grass (1855, the first of seven editions through 1891)

- Manly Health and Training (1858)[229]

- Drum-Taps (1865)

- Democratic Vistas (1871)

- Memoranda During the War (1876)

- Specimen Days (1882)

- The Wound Dresser: Letters written to his mother from the hospitals in Washington during the Civil War, edited by Richard M. Bucke (1898)

- Walt Whitman Speaks: His Final Thoughts on Life, Writing, Spirituality, and the Promise of America as told to Horace Traubel, edited by Brenda Wineapple (2019)[230]

See also

[edit]- LGBT history in New York (19th century)

- Walt Whitman and Abraham Lincoln

- Walt Whitman's lectures on Abraham Lincoln

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Reynolds, 314.

- ^ a b c Loving, 480.

- ^ a b Reynolds, 589.

- ^ a b Reynolds, 4.

- ^ a b Pound, Ezra. "Walt Whitman", Whitman, Roy Harvey Pearce, ed., Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1962: 8.

- ^ a b "Walt Whitman". Poetry Foundation. Archived from the original on July 4, 2024. Retrieved July 4, 2024.

- ^ Miller, 17.

- ^ "Walt Whitman". Encyclopædia Britannica. January 12, 2024. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

His ancestry was typical of the region: his mother, Louisa Van Velsor, was Dutch, and his father, Walter Whitman, was of English descent.

- ^ Loving, 29.

- ^ Loving, 30.

- ^ Reynolds, 24.

- ^ Reynolds, 33–34.

- ^ Ellen Freudenheim, Anna Wiener (2004). Brooklyn!, 3rd Edition: The Ultimate Guide to New York's Most Happening Borough. St. Martin's Press. p. 339. ISBN 9780312323318.

- ^ Loving, 32.

- ^ Reynolds, 44.

- ^ Kaplan, 74.

- ^ Callow, 30.

- ^ Callow, 29.

- ^ Loving, 34.

- ^ a b Reynolds, 45.

- ^ Callow, 32.

- ^ Kaplan, 79.

- ^ Kaplan, 77.

- ^ Callow, 35.

- ^ a b Kaplan, 81.

- ^ Loving, 36.

- ^ Callow, 36.

- ^ Loving, 37.

- ^ a b Reynolds, 60.

- ^ Loving, 38.

- ^ Kaplan, 93–94.

- ^ Kaplan, 87.

- ^ Loving, 514.

- ^ Stacy, 25.

- ^ Callow, 56.

- ^ Stacy, 6.

- ^ Brasher, Thomas L. (2008). Judith Tick, Paul E. Beaudoin (ed.). "Walt Whitman's Conversion To Opera". Music in the USA: A Documentary Companion. Oxford University Press: 207.

- ^ Reynolds, 83–84.

- ^ Merlob, Maya (2012). "Chapter 5: Celebrated Rubbish: John Neal and the Commercialization of Early American Romanticism". In Watts, Edward; Carlson, David J. (eds.). John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press. p. 119, n18. ISBN 978-1-61148-420-5.

- ^ Stacy, 87–91.

- ^ Alcott, Louisa May; Elbert, Sarah (1997). Louisa May Alcott on Race, Sex, and Slavery. Northeastern University Press. ISBN 978-1555533076.

- ^ a b Schuessler, Jennifer (February 20, 2017). "In a Walt Whitman Novel, Lost for 165 Years, Clues to Leaves of Grass". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 21, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ^ a b Schuessler, Jennifer (April 29, 2016). "Found: Walt Whitman's Guide to 'Manly Health'". The New York Times. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

Now, Whitman's self-help-guide-meets-democratic-manifesto is being published online in its entirety by a scholarly journal, in what some experts are calling the biggest new Whitman discovery in decades.

- ^ "Special Double Issue: Walt Whitman's Newly Discovered 'Manly Health and Training'". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. 33 (3). Winter–Spring 2016. ISSN 0737-0679. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ Whitman, Walt (1882). "Genealogy – Van Velsor and Whitman". Bartleby.com (excerpt from Specimen Days). Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

THE LATER years of the last century found the Van Velsor family, my mother's side, living on their own farm at Cold Spring, Long Island, New York State, ...

- ^ Onion, Rebecca (May 2, 2016). "Finding the Poetry in Walt Whitman's Newly Rediscovered Health Advice". Slate.com. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

a quirky document full of prescriptions that seem curiously modern

- ^ Cueto, Emma (May 2, 2016). "Walt Whitman's Advice Book For Men Has Just Been Discovered And Its Contents Are Surprising". Bustle. Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

And there are lots of other tidbits that, with a little modern rewording, would be right at home in the pages of a modern men's magazine—or even satirizing modern ideas about manliness because they're so over the top.

- ^ Turpin, Zachary (Winter–Spring 2016). "Introduction to Walt Whitman's 'Manly Health and Training'". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. 33 (3): 149. doi:10.13008/0737-0679.2205. ISSN 0737-0679.

a pseudoscientific tract

- ^ Kaplan, 185.

- ^ Reynolds, 85.

- ^ Loving, 154.

- ^ Miller, 55.

- ^ Miller, 155.

- ^ Kaplan, 187.

- ^ a b Callow, 226.

- ^ Loving, 178.

- ^ Kaplan, 198.

- ^ Callow, 227.

- ^ "Review of Leaves of Grass (1855)". The Walt Whitman Archive.

- ^ Kaplan, 203.

- ^ Staff, Harriet (July 18, 2024). "Ralph Waldo Emerson Found His Poets in Whitman & Dickinson". Poetry Foundation. Archived from the original on July 18, 2024. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

- ^ Reynolds, 340.

- ^ Callow, 232.

- ^ Loving, 414.

- ^ Kaplan, 211.

- ^ "Laura Walls | Department of English | University of Notre Dame". Archived from the original on July 21, 2024. Retrieved July 21, 2024.

- ^ Walls, Laura Dassow Henry David Thoreau: A Life, 394. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2017. ISBN 978-0-226-59937-3

- ^ Kaplan, 229.

- ^ Reynolds, 348.

- ^ Callow, 238.

- ^ Kaplan, 207.

- ^ Loving, 238.

- ^ Reynolds, 363.

- ^ Callow, 225.

- ^ Reynolds, 368.

- ^ Loving, 228.

- ^ Reynolds, 375.

- ^ Callow, 283.

- ^ Reynolds, 410.

- ^ a b Kaplan, 268.

- ^ a b c Reynolds, 411.

- ^ Callow, 286.

- ^ Callow, 293.

- ^ Kaplan, 273.

- ^ Callow, 297.

- ^ Callow, 295.

- ^ Loving, 281.

- ^ Kaplan, 293–294.

- ^ Reynolds, 454.

- ^ a b Loving, 283.

- ^ a b c Reynolds, 455.

- ^ a b Loving, 290.

- ^ Loving, 291.

- ^ Kaplan, 304.

- ^ O'Connor, William Douglas (1866). The Good Gray Poet. New York: Bunce and Huntington (The Walt Whitman Archive).

- ^ Reynolds, 456–457.

- ^ Kaplan, 309.

- ^ Loving, 293.

- ^ Kaplan, 318–319.

- ^ a b Loving, 314.

- ^ Callow, 326.

- ^ Kaplan, 324.

- ^ Callow, 329.

- ^ Loving, 331.

- ^ Reynolds, 464.

- ^ Kaplan, 340.

- ^ Loving, 341.

- ^ Miller, 33.

- ^ a b "Camden and the Last Years, 1875-1892 | Timeline | Articles and Essays | Walt Whitman Papers in the Charles E. Feinberg Collection | Digital Collections | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Haas, Irvin. Historic Homes of American Authors. Washington, D.C.: The Preservation Press, 1991: 141. ISBN 0-89133-180-8.

- ^ Loving, 432.

- ^ Reynolds, 548.

- ^ 1976 Bicentennial publication produced for the Borough of Laurel Springs. "Laurel Springs History". WestfieldNJ.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Reynolds, 586.

- ^ a b Loving, 479.

- ^ Kaplan, 49.

- ^ Reynolds, 587.

- ^ Callow, 363.

- ^ Griffiths, Rhys (March 2017), "Death of Walt Whitman" Archived March 19, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, History Today, volume 67, issue 3.

- ^ a b Reynolds, 588.

- ^ Theroux, Phyllis (1977). The Book of Eulogies. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 30.

- ^ Kaplan, 50.

- ^ Spitzka, Edw. Anthony (1907). "A Study of the Brains of Six Eminent Scientists and Scholars Belonging to the American Anthropometric Society, together with a Description of the Skull of Professor E. D. Cope". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 21 (4): 175–308. doi:10.2307/1005434. JSTOR 1005434. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ^ Kirmizi, Busra, and Martin Kopacik, "The Affinity between the Body, The Self and Nature in Whitman's 'Song of Myself'", in Academic research of SSaH 2016, p. 101. ISBN 978-80-906231-8-7.

- ^ Kaplan, 233.

- ^ Reynolds, 5.

- ^ Reynolds, 324.

- ^ Miller, 78.

- ^ Reynolds, 332.

- ^ Loving, 71.

- ^ Callow, 75.

- ^ Loving, 74.

- ^ Reynolds, 95.

- ^ Reynolds, 91.

- ^ Loving, 75.

- ^ Reynolds, 97.

- ^ Loving, 72.

- ^ Binns, Henry Bryan (1905). A life of Walt Whitman. London: Methuen & Co. p. 315. Archived from the original on October 15, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ a b c Reynolds, 237.

- ^ Loving, 353.

- ^ Kuebrich, David (2009). "Religion and the poet-prophet". In Kummings, Donald D. (ed.). A Companion to Walt Whitman. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 211–. ISBN 978-1-4051-9551-5. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ Lachs, John; Talisse, Robert, eds. (2007). American Philosophy: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 310. ISBN 978-0415939263.

- ^ D'Emilio, John and Estelle B. Freeman, Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America. University of Chicago Press, 1997. ISBN 0-226-14264-7

- ^ Fone, Byrne R. S. (1992). Masculine Landscapes: Walt Whitman and the Homoerotic Text. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

- ^ Loving, 184–185.

- ^ Norton, Rictor (November 1974). "The Homophobic Imagination: An Editorial". College English. 36 (3): 274. doi:10.2307/374839. JSTOR 374839. Archived from the original on September 30, 2024. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ "John Addington Symonds to Walt Whitman, 7 February 1872 (Correspondence) – The Walt Whitman Archive". whitmanarchive.org. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- ^ Reynolds, 527.

- ^ Reynolds, David S. (1996). Walt Whitman's America: A Cultural Biography. Vintage Books. pp. 198, 396, 577. ISBN 978-0-679-76709-1.

- ^ a b Loving, 19.

- ^ "Walt Whitman, Prophet of Gay Liberation". rictornorton.co.uk. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ Robinson, Michael. Worshipping Walt. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010: 142–143. ISBN 0691146314

- ^ Higgins, Andrew C. (1998). "Symonds, John Addington [1840–1893]". In LeMaster, J. R.; Kummings, Donald D. (eds.). Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ Miller, James E. Jr. (1998). "Sex and Sexuality". In LeMaster, J. R.; Kummings, Donald D. (eds.). Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ Tayson, Richard (2005). "The Casualties of Walt Whitman". VQR: A National Journal of Literature and Discussion (Spring). Archived from the original on October 13, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ Rothenberg Gritz, Jennie (September 7, 2012). "But Were They Gay? The Mystery of Same-Sex Love in the 19th Century". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ Loving, 123.

- ^ Kaplan, Justin (2003). Walt Whitman: A Life. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics. p. 287.

- ^ a b Shively, Charley (1987). Calamus Lovers: Walt Whitman's Working Class Camerados. San Francisco: Gay Sunshine Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-917342-18-9.

- ^ Reynolds, 487.

- ^ Kaplan, 311–312.

- ^ Stokes, John, Oscar Wilde: Myths, Miracles and Imitations, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 194, n.7.

- ^ "Gay Sunshine". www.leylandpublications.com. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ Kantrowitz, Arnie (1998). "Carpenter, Edward [1844–1929]". In LeMaster, J. R.; Kummings, Donald D. (eds.). Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ Arthur, Gavin The Circle of Sex, University Books, New York 1966.

- ^ Adams, Henry (2005). Eakins Revealed: The Secret Life of an American Artist. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 289. ISBN 978-0190288877.

- ^ Bohan, Ruth L. (April 26, 2006). Looking into Walt Whitman: American Art, 1850–1920 (1st ed.). University Park: Penn State University Press. p. 136.

- ^ Folsom, Ed (April 1, 1986). "An Unknown Photograph of Whitman and Harry Stafford". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. 3 (4): 51–52. doi:10.13008/2153-3695.1125.

- ^ Callow, 278.

- ^ Reynolds, 490.

- ^ Nelson, Paul A. "Walt Whitman on Shakespeare" Archived 2007-03-24 at the Wayback Machine. Reprinted from The Shakespeare Oxford Society Newsletter, Fall 1992: Volume 28, 4A.

- ^ Klammer, Martin (1998). "Free Soil Party". In LeMaster, J. R.; Kummings, Donald D. (eds.). Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ a b Reynolds, 117.

- ^ Loving, 110.

- ^ Reynolds, 473.

- ^ Reynolds, 470.

- ^ a b Hutchinson, George; Drews, David (1998). "Racial Attitudes". In LeMaster, J. R.; Kummings, Donald D. (eds.). Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ a b O'Reilly, Nathanael (2009). "Imagined America: Walt Whitman's Nationalism in the First Edition of Leaves of Grass". Irish Journal of American Studies. 1: 1–9. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ Kummings, Donald D.; LeMaster, J. R. (1998). Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia. Garland. p. 427.

- ^ Levin, Joanna (2018). Walt Whitman in Context. Cambridge University Press. p. 314.

- ^ Folsom, Ed (1997). Walt Whitman's Native Representations. Cambridge University Press. pp. 95–96.

- ^ Kaplan, 22.

- ^ Callow, 83.

- ^ Loving, 475.

- ^ Bloom, Harold. Introduction to Leaves of Grass. Penguin Classics, 2005.

- ^ C.F. Sixsmith Walt Whitman Collection, Archives Hub, archived from the original on April 30, 2011, retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ Ward, David C. (September 22, 2016). "What Langston Hughes' Powerful Poem 'I, Too' Tells Us About America's Past and Present". Smithsonian. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ Ginsburg's poem, "A Supermarket in California" Archived April 2, 2024, at the Wayback Machine, explicitly addresses Whitman.

- ^ Loving, 181.

- ^ Foley, Jack (2008). "A Second Coming". Contemporary Poetry Review. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ^ "For the Sake of People's Poetry by June Jordan". Poetry Foundation. November 7, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ Poets, Academy of American (April 1, 2019). "An Interview with Joy Harjo, U.S. Poet Laureate". poets.org. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ Meyer, Mary Edgar (1952). "Walt Whitman's Popularity among Latin-American Poets". The Americas. 9 (1): 3–15. doi:10.2307/977855. ISSN 0003-1615. JSTOR 977855. S2CID 147381491.

Modernism, it has been said, spread the name of Whitman in Hispanic America. Credit, however, is given to Jose Marti.

- ^ Santí, Enrico Mario (2005), "This Land of Prophets: Walt Whitman in Latin America", Ciphers of History, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 66–83, doi:10.1007/978-1-137-12245-2_3, ISBN 978-1-4039-7046-6, retrieved November 7, 2020

- ^ Molloy, S. (January 1, 1996). "His America, Our America: Jose Marti Reads Whitman". Modern Language Quarterly. 57 (2): 369–379. doi:10.1215/00267929-57-2-369. ISSN 0026-7929.

- ^ a b Cohen, Matt; Price, Rachel. "Walt Whitman in Latin America and Spain: Walt Whitman Archive Translations". whitmanarchive.org. The Walt Whitman Archive. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

Only with Vasseur's subsequent 1912 translation did Whitman become available and important to generations of Latin American poets, from the residual modernistas to the region's major twentieth-century figures.

- ^ Robinson, Michael. Worshipping Walt. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010: 143–145. ISBN 0691146314

- ^ Nuzum, Eric. The Dead Travel Fast: Stalking Vampires from Nosferatu to Count Chocula. Thomas Dunne Books, 2007: 141–147. ISBN 0-312-37111-X

- ^ a b c d Britton, Wesley A. (1998). "Media Interpretations of Whitman's Life and Works". In LeMaster, J. R.; Kummings, Donald D. (eds.). Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ Wilmington, Michael (June 2, 1989). "Movie Review: 'Poets Society': A Moving Elegy From Peter Weir". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ Jewell, Andrew; Price, Kenneth M. (2009). "Twentieth Century Mass Media Appearances". In Kummings, Donald D. (ed.). A Companion to Walt Whitman. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 211–. ISBN 978-1-4051-9551-5. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ Stevens, Daniel B. (2013). "Singing the Body Electric: Using ePortfolios to IntegrateTeaching, Learning and Assessment" (PDF). Journal of Performing Arts Leadership in Higher Education. IV (Fall): 22–48. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 12, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ "American Composers Orchestra – May 15, 1999 – Walt Whitman & Music". Archived from the original on April 27, 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ^ Sommerfeld, Paul (May 8, 2019), "Celebrating Walt Whitman's 200th Birthday" Archived August 24, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, In the Muse Performing Arts Blog, Library of Congress.

- ^ Music to accompany Whitman, a radio play by Norman Corwin

- ^ "PROGRAM NOTES: "Dooryard Bloom"" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2024.

- ^ When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd (Hindemith)

- ^ "Five Poems of Walt Whitman | Song Texts, Lyrics &…". Oxford Song. Archived from the original on September 16, 2024. Retrieved November 19, 2024.

- ^ Folsom, Ed (2004). "In Memoriam: Robert Strassburg, 1915–2003". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. 21 (3): 189–191. doi:10.13008/2153-3695.1733.

- ^ Cohen, Aaron I. (1987). International encyclopedia of women composers (2nd ed.). New York. ISBN 0-9617485-2-4. OCLC 16714846. Archived from the original on December 25, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Neilson, Kenneth P. (1963). The World of Walt Whitman Music: A Bibliographical Study. Kenneth P. Neilson.

- ^ A Sea Symphony

- ^ "Four Walt Whitman Songs". The Kurt Weill Foundation for Music. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "Frank Weise collection of Helen Weiss papers, circa 1940–1948, 1966". dla.library.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ Sessions, Roger/When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd, DRAM.

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony (May 31, 2015). "Review: Matthew Aucoin's Crossing Is a Taut, Inspired Opera". The New York Times.

- ^ Pop, Iggy; Beer, Paula; Böwe, Jule; Bruch, Volker; Fehling, Alexander; Gwisdek, Robert; Minichmayr, Birgit; Ostendorf, Josef [in German]; Rudolph, Lars; Sägebrecht, Marianne; Wuttke, Martin (August 25, 2019) [2014]. Grehn, Kai [in German] (ed.). "Iggy Pop spricht Walt Whitman – Kinder Adams – Children of Adam: Von Kai Grehn nach einem Text von Walt Whitman" (in German). RB/Deutschlandradio Kultur/SWR. Archived from the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2022. [1] [52:29]

- ^ Schöberlein, Stefan (2016). "Whitman, Walt, Kinder Adams/Children of Adam; Iggy Pop, Alva Noto, and Tarwater, Leaves of Grass (review)". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. 33 (3): 311–312. doi:10.13008/0737-0679.2210. ISSN 0737-0679.

- ^ "Welcome to Tzadik". www.tzadik.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ "Walt Whitman Bridge". Delaware River Port Authority of Pennsylvania and New Jersey. 2013. Archived from the original on November 12, 2017. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ^ a b "Delaware River Port Authority records on the naming of the Walt Whitman Bridge". Philadelphia Area Archives. Ms. Coll 1043. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ Jet. Johnson Publishing Company. September 22, 1997.

- ^ Reserved, Simon Property Group, L.P. and/or Its Affiliates (NYSE: SPG), © Copyright 1999–2022. "Walt Whitman Shops®". www.simon.com. Archived from the original on January 9, 2022. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ New Jersey to Bon Jovi: You Give Us a Good Name Yahoo News, February 2, 2009.

- ^ "Boystown unveils new Legacy Walk LGBT history plaques". Chicago Phoenix. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016.

- ^ Camp Walt Whitman Archived April 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine July 1, 2016.

- ^ Domius, Susan (August 14, 2008). "A Place and an Era in Which Time Could Stand Still". The New York Times. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ "Mercury". We Name the Stars. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ "Walt Whitman's Newly Discovered 'Manly Health and Training'", Walt Whitman Quarterly Review, Volume 33, Issue 3/4, 2016.

- ^ Wineapple, Brenda, "'I Have Let Whitman Alone': Horace Traubel's monumental chronicle of Whitman's reflections, ruminations, analyses, and affirmations" Archived February 23, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Review of Books, April 18, 2019.

Sources

[edit]- Callow, Philip. From Noon to Starry Night: A Life of Walt Whitman. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1992. ISBN 0-929587-95-2

- Kaplan, Justin. Walt Whitman: A Life. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1979. ISBN 0-671-22542-1

- Loving, Jerome. Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself. University of California Press, 1999. ISBN 0-520-22687-9

- Miller, James E. Walt Whitman. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc. 1962

- Reynolds, David S. Walt Whitman's America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage Books, 1995. ISBN 0-679-76709-6

- Stacy, Jason. Walt Whitman's Multitudes: Labor Reform and Persona in Whitman's Journalism and the First 'Leaves of Grass', 1840–1855. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-1-4331-0383-4

External links

[edit]Online editions

[edit]- Works by Walt Whitman in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Walt Whitman at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Walt Whitman at the Internet Archive

- Works by Walt Whitman at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Published Writings at Walt Whitman Archive

Archives

[edit]- The Walt Whitman Archive at the University of Nebraska Lincoln

- Walt Whitman papers at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- Walt Whitman documents at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- Walt Whitman, "The Bible as Poetry". Manuscript 1883 at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center.

- Walt Whitman collection 1884–1892 at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center.

- Walt Whitman collection. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- Walt Whitman collection, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania.

- Walt Whitman collection at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

- "The Untimeliness of the Walt Whitman Exhibition at the New York Public Library: An Open Letter to Trustees," by Charles F. Heartman, at the John J. Wilcox, Jr. LGBT Archives, William Way LGBT Community Center.

- Horace Traubel collection of Walt Whitman papers at Special Collections, University of Delaware Library, Museums and Press.

- Susan Jaffe Tane collection of Walt Whitman, 1842–2012, held by the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, New York Public Library.

- William E. Barton Collection of Walt Whitman Materials at the Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

Exhibitions

[edit]- Walt Whitman in His Time and Ours at Special Collections, University of Delaware Library, Museums and Press, February 12 to June 14, 2019

- Revising Himself: Walt Whitman and Leaves of Grass at the Library of Congress, "Exhibition Celebrates 150 Years of Walt Whitman's 'Leaves of Grass'", May 16 to December 3, 2005

- Whitman Vignettes: Camden and Philadelphia at Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania, May 28 to August 23, 2019

- Walt Whitman Bard of Democracy at the Morgan Library and Museum, June 7 to September 15, 2019

- Walt Whitman: America's Poet at the New York Public Library, March 29 to August 30, 2019

- Poet of the Body: New York's Walt Whitman at the Grolier Club, May 15 to July 27, 2019

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Historic sites

[edit]- Walt Whitman Birthplace State Historic Site Archived September 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Walt Whitman Camden Home Historic Site

Other external links

[edit]- Whitman Web – University of Iowa International Program

- Walt Whitman: Online Resources at the Library of Congress.

- The Walt Whitman Archive includes all editions of Leaves of Grass in page-images and transcription, as well as manuscripts, criticism, and biography.

- Walt Whitman: Profile, Poems, Essays at Poets.org.

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle Online. Brooklyn Public Library.

- Walt Whitman at Find a Grave

- Walt Whitman at IMDb

- Johnson, John A., and Lloyd D. Worley. "Criminals' Responses to Religious Themes in Whitman's Poetry" (Archive). In J. M. Day and W. S. Laufer (eds), Crime, Values, and Religion, Norwood, NJ: Ablex, 1987, 133–51.

- Walt Whitman

- 1819 births

- 1892 deaths

- 19th-century American journalists

- 19th-century American male writers

- 19th-century American novelists

- 19th-century American poets

- 19th-century American essayists

- 19th-century American LGBTQ people

- 19th-century pseudonymous writers

- American civil servants

- American Civil War nurses

- American humanists

- American male essayists

- American male journalists

- American male novelists

- American male poets

- American nationalists

- American religious skeptics

- American spiritual writers

- American people of Dutch descent

- American people of English descent

- Brooklyn Eagle people

- Burials at Harleigh Cemetery, Camden

- Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees

- Journalists from New York City

- American LGBTQ novelists

- American LGBTQ poets

- Male nurses

- Members of the American Anthropometric Society

- 19th-century mystics

- Novelists from New Jersey

- Novelists from New York (state)

- Pantheists

- People from Hempstead (village), New York

- People from Laurel Springs, New Jersey

- People from West Hills, New York

- People of New York (state) in the American Civil War

- Poets from New York (state)

- War writers

- Writers from Brooklyn

- Writers from Camden, New Jersey