Makthar (archaeological site)

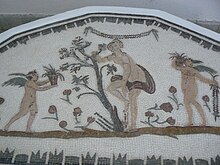

Venus in the bath surrounded by two lovers, Makthar Museum, Tunisia | |

| |

| Location | Tunisia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 35°51′20″N 9°12′23″E / 35.85556°N 9.20639°E |

The Makthar archaeological site, the remains of ancient Mactaris, is an archaeological site in Makthar, west-central Tunisia, a town on the northern edge of the Tunisian Ridge.

The site is one of the most extensive in the country, and much of it remains to be archaeologically explored in 2020, a situation comparable to that of Bulla Regia. Some of the reasons for this may be the relative remoteness of the region and the difficulty of integrating it into communication networks.

In addition to the numerous remains housed in an archaeological park, with only a few scattered elements excluded, a small museum displays various archaeological finds from the site.

Location

[edit]The site is located on the border between northwestern and central western Tunisia, 150 kilometers southwest of Carthage and 70 kilometers southeast of Sicca Veneria.

The city was built on the edge of a plateau at an altitude of 900 meters between the Ouzafa and Saboun wadi valleys.[1] Its location on an easily defensible site illustrates its primitive military vocation.

History

[edit]Numidian, then Roman city

[edit]Mactaris was inhabited as early as the 8th millennium BC, as evidenced by the fossilized snails' presence. The city was probably founded by Libyan populations, as indicated by the toponym MKTRM, translated into Latin as Mactaris. In the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, it was a relevant Numidian city that formed a privileged alliance with Carthage under the reign of King Massinissa (202–148 BC). The city benefited from the development of Carthage before receiving large numbers of refugees when Carthage fell in 146 BC. Massinissa finally took the city in 149 BC.[2]

The Neo-Punic period saw a definite development: stelae from the 1st century found at Bab El Aïn testify to the presence of a tophet; the main deity at that time was Baal Hammon.[2]

Mactaris underwent a late but real Romanization: In 46 BC, it obtained the status of a free city, but maintained three shophets in its local institutions until the beginning of the 2nd century, perhaps due to Numidian influence;[1] triumvirs replaced these magistrates in the same century.[2] Some families became Roman citizens under Emperor Trajan, and some attained equestrian rank as early as the reign of Commodus.[1]

Promoted as a colony under the name of Colonia Aelia Aurelia Mactaris between 176 and 180, the city benefited from the Roman peace from the end of the 1st century and enjoyed a certain prosperity.[3] At the end of the 2nd century, during the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, the city reached its peak, as evidenced by the numerous monuments that were built as the city spread over an area of more than ten hectares.

In the 3rd century, the city became the seat of a Christian bishopric and underwent the Donatist schism in the 5th century. At that time, the city had two cathedrals.[4] An epitaph known as the 'Harvester of Mactar,' preserved at the Louvre and dating back to the years 260–270,[5] recounts the career of a farm laborer who, after 23 years of work, obtained the minimum cens required to access the Senate of his city.[6] According to Gilbert Charles-Picard,[7] this ascent testifies to the "municipal decentralization that contributes to fighting against the concentration of political power and wealth." The city was integrated into the province of Byzacena during the reorganization of the empire by Diocletian.[4]

The decline of the city started with the Vandal invasions from 439 onwards. During Justinian's reign, forts were constructed in existing buildings, including the 'Great Baths.'[8] The decline was final in the 11th century, with the arrival of the Hilalian tribes.

Succession of excavations

[edit]The site has been known to travelers since the early 19th century, and excavations began in 1893, when the temple of Hathor Miskar was excavated. Excavations at the site began in 1944 under the direction of Gilbert Charles-Picard. The two forums were excavated from 1947 to 1956. From 1946 to 1955, it was the turn of the Schola Juvenes to be cleared.

After a brief hiatus, excavations resumed in 1960 following independence.[9]

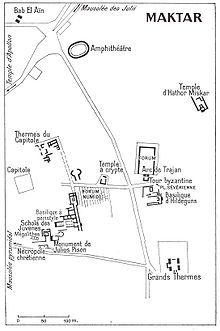

The site remains incompletely excavated due to its large surface area, and certain elements such as the Neo-Punic mausoleum, the Temple of Apollo, the Bab El Aïn arch, and the Julii mausoleum have been placed outside the archaeological park.

Buildings

[edit]Pre-roman buildings

[edit]

The site features a remarkable collection of megaliths that have been excavated. Comprising large slabs, the ensemble includes a space dedicated to worshipping the deceased during ashes-laying ceremonies. The megaliths functioned as collective burial sites.[10] Excavations of an intact burial chamber, conducted by Mansour Ghaki, unearthed a large number of ceramics of various origins, both local and imported. This material has been dated from the early 3rd century BC to the end of the 1st century.[10] On 17 January 2012, the Tunisian government nominated the complex for inclusion on UNESCO's World Heritage List as part of the royal mausoleums of Numidia, Mauritania, and pre-Islamic funerary monuments.[11]

Moreover, the site includes a Punic pyramidal mausoleum, similar to the mausoleum of Atban at Dougga. Archaeologists have also discovered a Numidian-era public square that likely served as the town's religious center due to the presence of temples. Among these temples was one dedicated to Augustus and Rome.[12]

The temple of Hathor Miskar is well-known for the extensive excavations carried out there, despite the inadequate preservation of the remains. At the core of the sanctuary, archaeologists found an altar dating back to approximately 100 BCE.[2]

Civil buildings

[edit]

The Schola Juvenes is a well-preserved building from the Severan period. It was excavated by Gilbert Charles-Picard and interpreted as the meeting place of the city's juvenile college due to an inscription.[13] The building was financed by Julius Piso and constructed on the site of a Flavian sanctuary dedicated to Mars. It was later rebuilt during the reign of Diocletian.[14]

Although the Roman Empire did not generally support freedom of association, it did allow certain forms of association, known as 'colleges', as long as they did not disrupt public order and were justified on religious grounds (such as piety and funeral solidarity) or in the public interest (such as the firemen's college). The second category comprises juvenile colleges, consisting of young men who perform public order functions in the city, such as night patrols. However, their primary function is to provide a social setting for the urban elite, although rural dwellers and the less wealthy could also join. In 238, at El Djem, it was the juvenile college that led the revolt that brought Gordian I to power.

Therefore, the historical significance of this monument can be understood by reconstructing the architectural framework of these important associations. The remains include a courtyard with porticoes, rooms for worship to the north, sanitary facilities to the east, and a meeting room to the west.[13] The layout follows the Hellenistic tradition of the quadrangular palestra with peristyle.[15]

Near the building are the remains of a trough building, whose purpose is uncertain. It may have been used to collect taxes in kind or annona.

The forum is located at the intersection of the decumanus and cardo, symbolizing the center of the Roman city. The 1,500 m2 square is remarkably well-preserved and surrounded by a portico. The square is enclosed by an arch, which remains one of the highlights of the site.[12]

The single-bay triumphal arch, built in honor of Emperor Trajan in 116, has been preserved and integrated into the Byzantine-era fortifications, with an adjoining tower. The building commemorates the change in the city's status and the founding of a new district.[16]

Another significant gate, Bab El Aïn, is located outside the archaeological park. In 1969, archaeologists discovered numerous Neo-Punic stelae in its masonry,[2] some of which are on display in the site museum.

Leisure buildings

[edit]The site showcases the remains of significant thermal baths built between the late 2nd and early 3rd centuries.[17] Among them are the 'Grand South Thermal Baths,' which are considered one of the most important in Roman Africa. The walls of these baths are preserved to a height of over twelve meters and feature a beautiful mosaic adorned with a labyrinth. Additionally, there are the 'Capitol Thermal Baths.'

The main thermal baths of Makthar, inaugurated in 199,[18] do not seem to have had a palaestra.[19] Yvon Thébert, however, considers that the palaestras were integrated into the construction with a symmetrical plan, the total area of which is approximately 4,400 m2, with 225 m2 for the sole frigidarium[18] from the Severan period, which occupies the center of the complex with the adjoining natatio pool and flanked by two apodyteria.[20] In the 4th or early 5th century, the facilities are reduced:[18] the complex is transformed into a fortress in the Byzantine period and equipped with a large masonry wall.

The Western Baths, also known as the 'Capitol Baths,' were converted into a church either in the 4th century, according to Alexandre Lézine, or in the 5th century, according to Gilbert Charles-Picard. Noël Duval, however, suggests that the latest possible date for the change in function of the building is the 6th century.[17] The building's surface area is not fully understood, although Yvon Thébert classifies it among medium-sized baths. To the east, the construction had arcades, of which elements of its northern part remain.[17]

An amphitheater, which has also been preserved at the entrance to the site, has undergone extensive restoration. The cavea structure is of a mixed type, with differences between the north and south: the northern part is built up, while the southern part takes advantage of the relief of the hill.[21] A unique system of cages for cattle access to the arena was also discovered.[22]

Religious buildings

[edit]

The Capitol site has been poorly preserved, but excavations have revealed a dedication linking the emperor to the Jupiter-Junon-Minerve triad.[23] Additionally, a temple to Bacchus was discovered. It is believed that a temple of Apollo replaced the sanctuary of Eshmoun, and this same process likely led to the creation of the temple of Liber Pater, which is the interpretatio romana of the Punic god Shadrafa.[2]

The site contains several basilicas, including the 'Rutilius Basilica' located just behind the museum. This particular construction has been studied extensively since its identification in the 19th century, most recently by Noël Duval.[24] It is believed that the building, which was constructed on the site of a sanctuary dedicated to Saturn, served as the city's cathedral.

The archaeological site includes a Vandal-era basilica called 'Hildeguns' with three naves and Byzantine tombs. The surviving remains of buildings from this period are rare, which adds value to the site.

Discoveries on site

[edit]Works in situ

[edit]Several works can be seen in situ thanks to the Makthar Museum's privileged location at the entrance to the archaeological park. However, the monuments may appear relatively bare. Notably, there is a fine mosaic in the labyrinth inside the 'Grand South Thermal Baths.'

Works deposited in various museums

[edit]

The epitaph of the 'Harvester of Mactar'[25] is a significant document that sheds light on the economic life of the countryside and the process of renewing municipal elites in the 2nd century. Discovered in 1882 by Joseph Alphonse Letaille, it is now housed at the Louvre. Gilbert Charles-Picard used it to illustrate the interconnectedness of rural and urban societies, considering the city's small size.[26]

The La Ghorfa stelae series, unearthed near Makthar at Maghrawa (formerly Macota), is widely distributed. The British Museum exhibits 22 stelae, the Louvre has two,[27] the Vienna Art History Museum showcases three, and the Bardo National Museum exhibits twelve. The last four stelae, discovered in 1967, are displayed at the Makthar Museum.[28]

Works deposited at the National Bardo Museum

[edit]

The lion sculpture, a limestone piece dating back to the 1st century and belonging to the Numido-Punic tradition,[29] was unearthed in 1952 in the northeastern necropolis of the city. It would have adorned a funerary monument.

The treatment of the subject is remarkable, particularly in the highlighting of the eyes and mane, making it an outstanding example of pre-Roman statuary.[30]

The La Ghorfa stelae from the series discovered at Maghrawa share a similar configuration. The artifact is divided into three stereotyped registers, each with its distinct features. The upper register depicts deities in human form, such as Saturn or Tanit. The central register displays a temple pediment with the dedicator standing next to an altar. The last register portrays a sacrificial scene, featuring the sacrificial animal and sometimes the sacrificer.[31]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Collectif 2006, p. 300.

- ^ a b c d e f Lancel, Serge; Charles-Picard, Gilbert (1992). "Maktar". Dictionnaire de la civilisation phénicienne et punique (in French). Turnhout: Brepols. p. 270. ISBN 2503500331.

- ^ Slim & Fauqué 2001, p. 105.

- ^ a b Collectif 2006, p. 301.

- ^ Translation (in French) and photograph of the inscription in Slim & Fauqué 2001, p. 144.

- ^ Slim & Fauqué 2001, p. 143.

- ^ Slim & Fauqué 2001, p. 147.

- ^ Slim & Fauqué 2001, p. 228.

- ^ Rachet, Guy (1994). Dictionnaire de l'archéologie (in French). Paris: Robert Laffont. p. 566. ISBN 978-2221079041.

- ^ a b Slim & Fauqué 2001, p. 89.

- ^ "Les mausolées royaux de Numidie, de la Maurétanie et les monuments funéraires pré-islamiques". whc.unesco.org (in French). Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ a b Slim & Fauqué 2001, p. 161.

- ^ a b Gros 1996, p. 383.

- ^ Le Bohec 2005, p. 129.

- ^ Gros 1996, p. 384.

- ^ Gros 1996, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Thébert 2003, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Thébert 2003, p. 144.

- ^ Gros 1996, p. 409.

- ^ Gros 1996, p. 410-411.

- ^ Slim & Fauqué 2001, p. 177.

- ^ Slim & Fauqué 2001, p. 177-178.

- ^ Gros 1996, p. 227.

- ^ Duval, Noël (1985). "Une hypothèse sur la basilique de Rutilius à Mactar et le temple qui l'a précédée". Revue des études augustiniennes (in French). 31: 20–45. doi:10.1484/J.REA.5.104508. ISSN 1768-9260.

- ^ CIL VIII, 11824; Dessau 7457.

- ^ Fantar, M'hamed Hassine (1982). De Carthage à Kairouan : 2 000 ans d'art et d'histoire en Tunisie (in French). Paris: Association française d'action artistique. p. 102. ISBN 978-2865450152.

- ^ Fantar 1982, p. 108.

- ^ Ouertani, Nayla (1994). "La sculpture romaine". In Jean-Paul Morel (ed.). La Tunisie, carrefour du monde antique (in French). Dijon: Faton. pp. 92–101. ISBN 978-2878440201.

- ^ Ouertani 1994, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Fantar 1982, p. 116.

- ^ Fantar 1982, p. 109.

Bibliography

[edit]Bibliography on Makthar

[edit]- Beschaouch, Azedine; Mahjoubi, Ammar; Charles-Picard, Gilbert (1963). "Pagus Thuscae et Gunzuzi". CRAI (in French). 107 (2): 124–130. doi:10.3406/crai.1963.11535. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Charles-Picard, Gilbert (1957). "Civitas Mactaritana". Karthago (in French). 8.

- Charles-Picard, Gilbert (1982). "Essai d'interprétation du sanctuaire de Hoter Miscar à Maktar". Bac 18B (in French): 17–20.

- Charles-Picard, Gilbert (1974). "Les fouilles de Mactar (Tunisie). 1970–1973". CRAI (in French). 118 (1): 9–33. doi:10.3406/crai.1974.12951. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Charles-Picard, Gilbert (1953). "Les places publiques et le statut municipal de Mactar". CRAI (in French). 97 (1): 80–82. doi:10.3406/crai.1953.10065. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Charles-Picard, Gilbert (July 1954). "Mactar" (PDF). Bulletin économique et social de la Tunisie (in French): 63–78. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Charles-Picard, Gilbert (1977). "Recherches archéologiques franco-tunisiennes à Mactar. 1, la maison de Vénus ; 1, stratigraphies et étude des pavements". BEFR (in French) (34).

- Fantar, M'hamed Hassine (1963–1964). "Les nouvelles inscriptions monumentales néopuniques de Mactar". Karthago (in French). 12: 45–59.

- M'Charek, Ahmed (1982). "Aspects de l'évolution démographique et sociale à Mactaris aux iie et iiie siècles apr. J.-C". Tunis University (in French). Tunis.

- Monchicourt, Charles (1901). "Le massif de Mactar, Tunisie centrale". Annales de Géographie (in French). 10 (52): 346–369. doi:10.3406/geo.1901.5013. ISSN 0003-4010. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Prévot, Françoise (1984). "Recherches archéologiques franco-tunisiennes à Mactar. 1, la maison de Vénus". BEFR (in French) (34).

- Prévot, Françoise (1984). "Recherches archéologiques franco-tunisiennes à Mactar. 5, les inscriptions chrétiennes". BEFR (in French). 34 (34). Retrieved 9 November 2020.

General bibliography

[edit]- Aïcha Ben Abed (1992). Le musée du Bardo (in French). Tunis: Cérès. ISBN 997370083X.

- Briand-Ponsart, Claude; Hugoniot, Christophe (2005). L'Afrique romaine : de l'Atlantique à la Tripolitaine, 146 av. J.-C. - 533 apr. J.-C (in French). Paris: Armand Colin. ISBN 2200268386.

- Corbier, Paul; Griesheimer, Marc (2005). L'Afrique romaine : 146 av. J.-C. - 439 apr. J.-C (in French). Paris: Ellipses. ISBN 2729824413.

- Jean-Claude Golvin (2003). L'antiquité retrouvée (in French). Paris: Errance. ISBN 287772266X.

- Gros, Pierre (1996). L'architecture romaine du début du iiie siècle av. J.-C. à la fin du Haut-Empire (work used to write the article) (in French). Vol. 1: Monuments publics. Paris: Picard. ISBN 2708405004.

- Christophe Hugoniot (2000). Rome en Afrique: de la chute de Carthage aux débuts de la conquête arabe (in French). Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 2080830031.

- André Laronde; Jean-Claude Golvin (2001). L'Afrique antique (in French). Paris: Taillandier. ISBN 2235023134.

- Le Bohec, Yann (2005). Histoire de l'Afrique romaine (work used to write the article) (in French). Paris: Picard. ISBN 2708407511.

- Lipinski, Edward (dir.) (1992). Dictionnaire de la civilisation phénicienne et punique (work used to write the article) (in French). Turnhout: Brepols. ISBN 2503500331.

- Mahjoubi, Ammar (2000). Villes et structures de la province romaine d'Afrique (in French). Tunis: Centre de publication universitaire. ISBN 9973937953.

- Slim, Hédi; Fauqué, Nicolas (2001). La Tunisie antique : de Hannibal à saint Augustin (work used to write the article) (in French). Paris: Mengès. ISBN 285620421X.

- Thébert, Yvon (2003). Thermes romains d'Afrique du Nord et leur contexte méditerranéen (work used to write the article) (in French). Rome: École française de Rome. ISBN 2728303983.

- Collectif (1994). La Tunisie, carrefour du monde antique. Les dossiers d'archéologie (in French). Dijon: Faton. ISBN 978-2-87844-020-1.

- Collectif (2006). L'Afrique romaine, 69-439 (work used to write the article) (in French). Neuilly-sur-Seine: Atlande. ISBN 2350300021.

External links

[edit]- Entry in a dictionary or general encyclopedia: Nationalencyklopedin

- Authority control: Israel

- "Maktar. Always controlling the border". lexicorient.com. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- "Makthar, l'antique Mactaris". inp2020.tn (in French). 7 September 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.