Maata Horomona

Maata Horomona | |

|---|---|

Horomona in 1912 | |

| Born | 1893 |

| Died | 1939 (aged 45–46) Rotorua, New Zealand |

| Nationality | New Zealander |

| Occupation(s) | Haka dancer, actress |

| Notable work | Loved by a Maori Chieftess Hinemoa |

Maata Horomona (also known as Maata Gillies; 1893 – 1939) was a New Zealand haka performer and film actress.

In 1909, she was part of a troupe of traditional Māori dancers who performed for several months in New York, creating an interest in their culture. In 1912, she starred in three films shot by Gaston Méliès in New Zealand: Loved by a Maori Chieftess, Hinemoa and How Chief Te Ponga Won His Bride. These films, all released in 1913 only in the United States and considered lost, were the first fiction films shot in New Zealand. Maata Horomona was also the first non-Caucasian actress, in 1913, to have her portrait published in the Motion Picture Story Magazine's gallery of famous actors, eleven years before the second, Anna May Wong.

Maata Horomona's brief career illustrated several aspects of the New Zealand and international perception of Māori culture: the tension between the enduring stereotype of the beautiful, humble and easygoing vahiné (young woman from Tahiti), on the one hand, and the assimilation of the Māori and the disappearance of their traditional culture, on the other. It also witnessed the emergence of themes underlying the portrayal of Māori in cinema, divided between the legendary representation of a mythical Eden, the problems linked to integration between the descendants of settlers and indigenous people in New Zealand, and the tourist exploitation of Māori exoticism to promote the country.

Haka dancer

[edit]Maata Horonoma was born in 1893 in Ohinemutu,[1][2][3][note 1] a village located in the geothermal valley of the North Island nicknamed geyserland, inhabited by Māori even before the nearby sites of Rotorua, a spa town developed from 1880 onwards, where Gaston Méliès lodged during his stay in the region, and Whakarewarewa, a fortified village reconstituted on the initiative of the New Zealand government to promote tourism between 1907 and 1909, where Méliès filmed his fictions.[4] In 1912, when she began a very brief film career, she was probably employed in the village of Whakarewarewa, where she performed traditional Māori dances for tourists, and had probably known Frederick Bennett for several years, who recommended her as an actress.[2]

Bennett was a New Zealand Anglican priest with Irish-Māori heritage. He played a significant role in the late nineteenth century in promoting Māori culture through Western-style theatrical shows. Hailing from the same village as Horomana, the future bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Waiapu,[5] Bennett organized performances depicting Māori traditions and the Hinemoa legend. These shows, featuring choirs, tableaux vivants, and dance, were led by Māori troupes, notably the Rotorua Maori Entertainers.[6] Marianne Schultz notes that these theatrical presentations reflected a convergence of Bennett's advocacy for the political assimilation of the Māori, the intentional tourist development in Rotorua by the New Zealand government, and societal changes marked by interracial marriages and pakeha settlement in traditionally Māori-inhabited areas.[7]

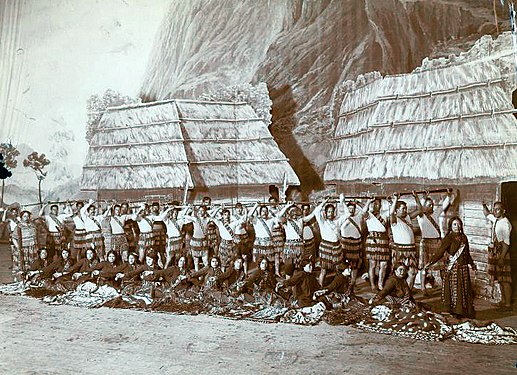

This convergence was particularly evident when, in 1908, an American military fleet led by Admiral Sperry paid an official visit to Rotorua to attend the inauguration of the thermal baths run by Arthur Stanley Wohlmann. On this occasion, the government agency for the promotion of tourism created in 1901 organized, with Bennett's help, a Māori reception for the American admiral and the two hundred officers accompanying him, featuring haka and poï performances, whose coverage in the American press led the directors of the Hippodrome theater, New York's largest stage, to invite a troupe of Māori dancers to perform there the following year.[8][9]

Maata Horomona was part of the troupe of 27 men and 16 women who embarked on a 9-month tour in July 1909.[2] The choice of members was the subject of conflicting considerations between the New Zealand intermediaries, including Bennett, and the American organizers: while the New Zealanders favored legitimacy and technical skills, the Americans had racial stereotypes in mind, notably that of the vahiné (young woman from Tahiti),[10] wanted the arrival of "tanned beauties" to "titillate" the New York spectators and were ultimately disappointed that the troupe included only "two or three" young girls,[11] among them Maata Horonoma.

The show staged at the Hippodrome was a great success, even if it was based on a misunderstanding: the New Zealanders thought they were being appreciated out of an interest in their culture, while the American public came to see a variation on a type of entertainment popular since the 19th century, the representation of an exotic form of savagery, attended in particular by anthropologists from the American Museum of Natural History.[12] However, this preconception was contradicted by the cultural level of the Māori: not only did they speak perfect English and demonstrated a mastery of Western manners, but the women in the troupe voted in their homelands, while American suffragettes were still fighting for a similar right. The American press embroidered on these paradoxes without altering the stereotypes of the cannibal and the vahiné:[13]

Vigorous Maori warriors and New Zealand vahines strolled down Fifth Avenue, conscious of their success. The men carried bone hatchets in their automobiles. The women wore high-heeled French shoes on their little feet, which a few weeks ago were dancing naked on the sand [...], then duck out to speak at some suffragette meeting about the antipodes' advanced social legislation.[14]

Méliès actress

[edit]In 1901, Georges Méliès' older brother Gaston, who was not particularly predisposed to a career in cinema, found himself widowed and unemployed; at the same time, his brother needed someone in New York to promote his films on the American market and combat counterfeiting; Gaston, aged 50, decided to move to New York and set up an American agency, Star Film, to fulfill these two missions.[17][18] Until 1908, his activity was essentially administrative, but in 1909 he joined the Motion Picture Patents Company, a cartel headed by Thomas Edison, which controlled film distribution but required its members to produce at least one one-reel film (about ten minutes)[19] to supply exhibitors. With his brother Georges' output dwindling at the same time, Gaston Méliès was forced to start producing films himself in 1909. Having decided to specialize in Westerns, for which the American public of the time had a strong appetite, Gaston Méliès took the highly innovative step of setting up a studio in San Antonio, not only because of the climate and sunshine, but also because of the availability of real cowboys.[19] He shot some sixty one-reel films there, at an average rate of two per week, characterized, according to Frank Thomson, by "an interesting mix of respect and negative stereotyping of Indian and Mexican protagonists".[19] In 1911, after moving his studio to California, tired of shooting westerns and anticipating a desire for novelty on the part of the public, Gaston Méliès embarked on an original project: having accumulated enough films to supply distributors for a few months, he organized an expedition to the southern hemisphere, with a crew of some fifteen actors and technicians, planning to shoot both exotic fictions and documentary travelogues.[17] Méliès explained to the press that he felt audiences were tired of cowboys and American prairie life, and that he wanted to innovate by presenting in film the customs of South Sea inhabitants, in dramatic or educational form, with his actors playing the lead roles and natives the supporting ones. He insisted that he wanted to avoid shooting in studios, but rather on natural sets, so that every detail would be true to life.[20]

Leaving San Francisco in July 1912, he made his first stop in Tahiti in August, where he stayed for around ten days and shot several films. He was "very disappointed that the natives were already too civilized to serve easily in the views", and was struck both by the women's morals, which he found "more than a little loose", and by the Tahitians' enthusiasm for Westerns.[21] Méliès and his team arrived in New Zealand on October 12, 1912, where they stayed for a month before leaving for Australia.[22] Even before their arrival, the New Zealand press anticipated that he would be filming native dances "in appropriate landscapes",[23][24] or even more precisely, that after a week in Wellington he would travel to Rotorua, "where local color was as abundant as it was easy to obtain",[25] to shoot scenes inspired by the legend of Hinemoa and the hakas,[26] "no doubt" with the participation of Māori and against a backdrop of geysers.[27]

The New Zealand government, keen to develop foreign tourism and aware of the project's potential spin-offs, lent its support.[28] Walter Blow, head of the government tourism agency in Rotorua,[29] whom Méliès found "perfect",[30] put him in touch with a local specialist in Maori culture, James Cowan, who acted as "general advisor and interpreter"[31] and also contributed to the scripts.[32] Cowan recommended that Méliès shoot in Whakarewarewa, a reconstructed Maori village in the valley of the same name near Ohinemutu,[33] and put him in touch with Reverend Bennett,[28] whom Méliès described as "a pastor, half-Maori blood, who hasda great influence on his fellows and lead a troupe of Maoris [sic] who did all sorts of exercises".[30] Encouraged by Bennett's efficiency and the intelligence of the Maori actors the latter helped him direct, Méliès, who had just fired his director Bertram Bracken and Bracken's wife, actress Mildred Bracken, as well as actress Betty-Irène Tracy and actors William Ehfe, Sam Weil and Henry Stanley, readily adapted to this new situation and decided to give a prominent place to local actors.[34] Méliès later wrote from Java to his son:

When I saw the first negatives made with white people wearing Maori make-up, I realized that it wasn't right, and that was one of the big considerations that made me decide to get rid of part of the troupe in Rotorua, where, incidentally, I'd worked almost exclusively with natives. And that's what happens, or will happen, wherever we go.[35]

New Zealand filmmaker Rudall Hayward, whose uncle had negotiated with Méliès an unsuccessful project to distribute the latter's films in New Zealand,[36] maintained that before making Maata Horonoma the star of his New Zealand fictions, Méliès first tried out his young wife Hortense, previously burnished with cocoa.[37]

On the contrary, Méliès, who had now assumed the role of de facto director,[38] was delighted with his Maori actors, especially Maata Horomona, who was his "vedette",[1] writing:

Very good people, very intelligent, who seem to understand nothing when you explain to them what they have to do, and who carry out to the letter and with intelligence what is asked of them. Whereas Mildred [Bracken] had to be lectured several times to make her understand what she had to do, all I had to do was explain very slowly to Ma[at]a what I wanted her to do, and she would do it at once with the natural grace that one notices in her acting.[39]

At the end of the shoot, Maata and the "Maori chief" presented Méliès with a few gifts: a carved gourd, a mat, a spear and a "Maori skirt". For his part, Méliès gave his star his photographic portrait and the sum of 2 pounds (just under 400 2022 dollars).[40]

After the departure of Méliès, Maata Horomona stopped making films. She married a Maori, Tureriao Gillies, gave him several children.[note 2] and died in 1939 in Rotorua.[2]

Unlikely star

[edit]The relationship between silent-film stars and their fans developed with the emergence of a specialized press aimed at moviegoers, one of the first of which was the monthly Motion Picture Story Magazine, published from 1911 onwards.[43][44] As early as its second issue, this magazine devoted its first pages to a series entitled Personalities of the Picture Players, featuring full-page actor portraits designed to be cut out and pasted into albums by readers.[45] In the May 1913 issue, this gallery featured a portrait of Maata Horonoma, in traditional Maori dress and with a tattoo on her chin, accompanied by the words "Méliès", meaning that she was under contract to the Méliès studio, and that she was the native leading woman in a film entitled Hinemoa.[46] This feature was preceded, in the April 1913 issue, by a seven-page article by Peter Wade recounting the plot of the film Hinemoa;[47] and followed, in the June 1913 issue, by a brief reminder that Gaston Mélès was then touring the world, and then adding, in response to a reader's real or imaginary question: "Yes, Maata Horonoma is really an actress. Kia Ora (which means good luck in Maori)!"[48]

Maata Horomona's presence in this magazine's celebrity gallery was doubly paradoxical. On the one hand, she was a very little-known actress at the time – so much so that the magazine saw fit to specify that she was "really an actress" – having only appeared in a very small number of short films, each of which sold around ten copies;[49] on the other hand, she was a Maori actress, at a time when non-Caucasian roles were generally played by Caucasian actors wearing masks. In fact, Maata Horomona enjoyed the singular honor of being the first non-Caucasian actress to be included in Motion Picture Story Magazine's gallery of personalities.[2]

This apparent paradox can be explained by the way the magazine operated. It enjoyed the support of the Motion Pictures Patent Company, the cartel headed by Thomas Edison and to which Gaston Méliès' American Star Film Company belonged, on condition that it only promoted production companies that were members.[50] The actors featured in this way were not selected by the newspaper on the basis of their popularity, but the choice was made by the producers, who paid $200 a month for a guaranteed number of articles and photographs.[51]

As David Pfluger observed, Maata Horomona's inclusion in Motion Picture Story Magazine's gallery of famous actors, surprising as it may seem at first glance, was "neither arbitrary nor unthinkable". It illustrated the American public's interest in the Māori as an exotic race, but also the stereotypes associated with them, in particular the one, particularly attractive to the magazine's male readers, of the humble, submissive exotic beauty.[2]

Filmography

[edit]Maata Horomona appeared in the three fiction films produced by Gaston Méliès over a three-week period during his stay in New Zealand, but does not appear to have contributed to the documentaries shot during the same stay,[note 3] shot simultaneously but by a different crew.[note 4] These three films were the first fiction films shot in New Zealand,[52][53] and were only distributed in the US,[54][note 5] where they are reputed to have been lost.[55] The three films were scripted by Edward Mitchell, an Australian novelist and journalist who had been part of the Méliès team,[56] with the assistance of James Cowan. They were directed by Gaston Méliès, assisted by Pastor Bennett, and cinematographed by Hugh McClung.[57]

Reception

[edit]Based on the positive reviews published by The Moving Picture World,[59] several authors felt that the three films were well received by the public, who appreciated their novelty.[54][36] On the other hand, Jacques Malthète stated that all the films shot by Gaston Méliès in New Zealand and during his trip to the southern hemisphere sold poorly: only ten copies or so for each film, compared with 70 to 80 copies for the American westerns.[60][note 8]

Analysis

[edit]Now that these films have disappeared, silent film specialists are unable to observe either Méliès' direction or Horomata's acting, and their analyses are often limited to scripts.[52]

According to Martin Blythe, the first films shot in New Zealand fell into two successive and distinct categories: first, "imperial romances" in Maori country (Maoriland) shot by English, French and American directors from 1910 to 1920, then "national romances", shot by New Zealand directors from 1920: "the first were set in an eternity outside time, employing a Romeo-and-Juliet-style narrative plot in which true love triumphed over tribal conflict; the second were historically situated, playing with the notion of métissage to help construct a national identity".[61] Imperial romances took an ethnographic approach, depicting the land of the Māori[61] as a paradise before the fall; national romances took a historical approach, recounting the quest for a utopia after the fall, that of New Zealand as the land of the Māori. According to Blythe, the stories of Hinemoa or Te Ponga, with their noble savages and beautiful vahines, ending in inter-tribal marriages, were perfect examples of imperial romances, as attested by the fact that the Hinemoa legend was – after Méliès – the subject of several silent films.[62]

For their part, Alistair Fox, Barry Keith Grant and Hilary Radner, while considering that Hinemoa and How Chief Te Ponga Won His Bride, drawn from Maori legends, fitted into the first of Blythe's two categories, pointed out that the same was not true of Loved by a Maori Chieftess, where the relationship between the "English trapper" and the beautiful Māori princess fitted into the second. Its screenplay was clearly designed to satisfy the public's taste for melodrama and the exotic, but also reflected the desire of the white settlers to be accepted by the natives and, consequently, the importance of James Cowan's contribution.[63]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Maata Horomoma was, according to David Pfluger's research, the daughter of Miriata Te Koki, also known as Ngaamo Pera. Pfluger, Quintana & Pons (2018)

- ^ One of his sons, Bom Gillies, is known as the last survivor of the Maori Battalion. Bathgate, Benn (December 31, 2021). "Last survivor of the 28th Māori Battalion Knighted". Stuff.

- ^ The documentaries produced by Gaston Méliès in New Zealand are : The River Wanganui (394 feet, released April 3, 1913 in the U.S.), A Trip To the Waitomo Caves (119 feet, released April 24, 1913 in the U.S.), In the Land of Fire (1000-foot unit, released August 21, 1913 in the U.S.), Maoris of New Zealand (1000 feet, released April 10, 1913 in the U.S.) and A Trip Through the North Island of New Zealand from Auckland to Wellington (1000 feet, released May 8, 1913).

- ^ Anthropologist Patrick O'Reilly was confused by the existence of these documentaries: in 1949, he described the three films as "fictionalized documentaries". (O'Reilly, Patrick (1949). "Le " documentaire " ethnographique en Océanie". Journal de la Société des océanistes (in French). 5. doi:10.3406/jso.1949.1630., Tobing Rony, Fatimah (1996). The Third Eye : Race, Cinema, and Ethnographic Spectacle. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 85. ISBN 0822318407., Hockings, Paul; de Brigard, Émilie (1995). "The History of Ethnographic Film". Principles of Visual Anthropology. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 18–19.) Following O'Reilly, Marc-Henri Piault analyzed these films as proceeding from a "fictional organization of reality", the fiction taking place in a "relatively realistic" setting and even allowing, according to this author, "glimpses of different aspects of village life and, of course, footage of impressive dances and war canoes". (Piault, Marc-Henri (2011). "Vous avez dit fiction ? : À propos d'une anthropologie hors texte". L'Homme (in French) (198–199): 159–190. doi:10.4000/lhomme.22739.)

- ^ On the other hand, the film Trahison au pays des Maoris, released in France in September 1913, was actually shot in Australia, the French title confusing Māori and Aborigines. (Malthète, Jacques (1993). "Les frères Méliès en 1913 : l'année terrible". 1895 (in French). 1: 108–119. doi:10.3406/1895.1993.1015.)

- ^ Curiously, the "sculpted gourd" is present in each of these photographs.

- ^ The first photo is considered by Jacques Malthète to relate to Loved by a Maori Chieftess(Méliès & Malthète 1988, p. 44.) and no explanation is given as to why the second photograph also illustrates Hinemoa

- ^ However, Jacques Malthète made no distinction between the commercial success of melodramas and travelogues. Yet, as Jennifer Lynn Peterson pointed out, it was the latter genre in particular that Gaston Méliès seems to have misjudged in the light of low public demand. (Peterson, Jennifer Lynn (2013). Education in the School of Dreams: Travelogues and Early Nonfiction Film. New York: Duke University Press. p. 96.)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Méliès & Malthète 1988, p. 45.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pfluger, Quintana & Pons 2018.

- ^ Nicholas, Jill (April 23, 1916). "Saddest day of the year' for survivor". Rotorua Daily Post.

- ^ McClure, Margaret (2004). The Wonder Country: Making New Zealand Tourism. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

- ^ Bennett, Manu A. (1996). "Bennett, Frederick Augustus". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography..

- ^ Schultz, Marianne (2011). "'The Best Entertainment of Its Kind Ever Witnessed in New Zealand': The Rev. Frederick Augustus Bennett, the Rotorua Maori entertainers and the Story of Hinemoa and Tutanekai". Melbourne Historical Journal. 39 (1). ISSN 0076-6232.

- ^ Schultz 2014, pp. 128–131.

- ^ Schultz 2014, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Werry, Margaret (2005). "The Greatest Show on Earth: Political Spectacle, Spectacular Politics, and the American Pacific". Theatre Journal. 57 (3): 355–382. doi:10.1353/tj.2005.0124. JSTOR 25069669.

- ^ Tcherkézoff, Serge; Blanchard, Pascal; Bancel, Nicolas; Boëtsch, Gilles; Thomas, Dominic; Taraud, Christelle (2018). "La construction du corps sexualisé de la Polynésienne dans l'imaginaire européen". Sexe, race et colonies: La domination des corps du XV siècle à nos jours (in French). Paris: La Découverte.

- ^ Schultz 2014, p. 180.

- ^ Schultz 2014, p. 204.

- ^ Boulay, Roger (2000). Kannibals et vahinés: imagerie des mers du Sud (in French). La Tour d’Aigues: Éditions de l'Aube..

- ^ "The Maoris in New York. "South Sea Sufragettes" : Some Yankee Embellishment". The New Zealand Herald. October 21, 1909..

- ^ Schultz 2014, p. 206.

- ^ Schultz 2014, p. 210.

- ^ a b McInroy, Patrick (October 1979). "The American Méliès". Sight and Sound.

- ^ Méliès & Malthète 1988, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Thompson, Frank (1995). "The First Picture Show: Gaston Méliès's Star Film Ranch, San Antonio, Texas, 1910–1911". Literature/Film Quarterly. 23 (2). ProQuest 226992713.

- ^ "Tired of Cowboys: Picture-makers in South Seas". Dominion. August 19, 1912.

- ^ Méliès & Malthète 1988, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Méliès & Malthète 1988, pp. 41–45.

- ^ "Theatrical Notes". Wairarapa Daily Times. August 24, 1912.

- ^ "South Sea Pictures". Poverty Bay Herald. August 28, 1912.

- ^ "Picture-Making". New Zealand Times. September 13, 1912.

- ^ "Novelist and Journalist". Dominion. September 13, 1912.

- ^ "Footlight Flashes". Evening Star. September 16, 1912.

- ^ a b Derby, Bennett & Beirne 2012, p. 42.

- ^ "Untitled". Auckland Star. October 26, 1907.

- ^ a b Méliès & Malthète 1988, p. 41.

- ^ "Personal Items". Dominion. September 17, 1912.

- ^ "By "Movie Fan"". Grey River Argus. February 6, 1917.

- ^ Bory, Stéphanie (2015). "La gestion éco-touristique de la vallée de Whakarewarewa en Nouvelle-Zélande: promotion ou subversion de la culture māorie ?". ELOHI (7): 101–120. doi:10.4000/elohi.489.

- ^ Méliès & Malthète 1988, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Méliès & Malthète 1988, p. 85.

- ^ a b Martin, Helen; Edwards, Sam (1997). New Zealand Film, 1912–1996. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 20..

- ^ Babington, Bruce (2007). A History of the New Zealand Fiction Feature Film. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 35..

- ^ Millet, Raphaël (2016). "Gaston Mèliès and His Lost Films of Singapore". Biblioasia. 12 (1).

- ^ Méliès & Malthète 1988, p. 46.

- ^ "Inflation calculator". Reserve ank of New Zealand..

- ^ "Gaston Méliès, 1912". Teara..

- ^ Hoffman, Doré (February 8, 1913). "Melies in New Zealand". The Moving Picture World.

- ^ Sternheimer, Karen (2014). Celebrity Culture and the American Dream: Stardom and Social Mobility. Londres: Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 9781317689683.

- ^ Fuller, Kathryn (1996). "Motion Picture Story Magazine and the Gendered Construction of the Movie Fan.". At the Picture Show: Small-Town Audiences and the Creation of Movie Fan Culture. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- ^ Anselmo, Diana W. (2019). "Bound by Paper: Girl Fans, Movie Scrapbooks, and Hollywood Reception during World War I". Film History. 31 (3): 141. doi:10.2979/filmhistory.31.3.06.

- ^ "Gallery of Picture Players". The Motion Picture Story Magazine. May 1913.

- ^ a b Wade, Peter (April 1913). "Hinemoa (Méliès)". The Motion Picture Story Magazine.

- ^ "Answers to Inquiries". The Motion Picture Story Magazine: 148. June 1913.

- ^ Malthête, Jacques (1990). "Biographie de Gaston Méliès". 1895, revue d'histoire du cinéma (in French). 7 (7): 85–90.

- ^ Slide 1994, p. 40.

- ^ Slide 1994, p. 140.

- ^ a b Fox, Grant & Radner 2011, p. 18.

- ^ Fox, Alistair (2017). Coming-of-Age Cinema in New Zealand: Genre, Gender and Adaptation. Édimbourg: Edinburgh University Press. p. 17.

- ^ a b Derby, Bennett & Beirne 2012, p. 44.

- ^ New Zealand Film Archive (1982). "The "Lost" Melies New Zealand Films". FIAF Information Bulletin (23). ProQuest 235891998.

- ^ Mitchell, Edmund (1913). "Filming the South Seas: Adventures of a Motion Camera Among the Pacific Islands". Sunset. 31 (5).

- ^ Méliès & Malthète 1988, p. 49.

- ^ Laroche, Edwin (1913). "How Chief Te Ponga Won His Bride (Melies)". The Motion Picture Story Magazine.

- ^ Bush, W. Stephen (March 8, 1913). "Loved by a Maori Chieftess". The Moving Picture World.

- ^ Malthète, Jacques (1990). "Biographie de Gaston Méliès". 1895. 7 (7): 85–90.

- ^ a b Blythe 1994, p. 10.

- ^ Blythe 1994, p. 17.

- ^ Fox, Grant & Radner 2011, pp. 18–20.

Bibliography

[edit]- Blythe, Martin (1994). Naming the Other: Images of the Maori in New Zealand Film and Television. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press.

- Derby, Mark; Bennett, James E.; Beirne, Rebecca (2012). "Méliès in Maoriland". Making Film and Television Histories: The Making of the First New Zealand Feature Films. Londres: I.B. Tauris.

- Fox, Alistair; Grant, Barry Keith; Radner, Hilary (2011). New Zealand Cinema: Interpreting the Past. Bristol: Intellect..

- Méliès, Gaston; Malthète, Jacques (1988). Le Voyage autour du monde de la G. Méliès Manufacturing Company: juillet 1912 – mai 1913. Paris: Les Amis de Georges Méliès.

- O'Reilly, Patrick (1949). "Le " documentaire " ethnographique en Océanie". Journal de la Société des océanistes. 5. doi:10.3406/jso.1949.1630.

- Pfluger, David; Quintana, Angel; Pons, Jordi (2018). "Maata Who … ?: The Native Maori Woman Who Made it into the Gallery of Picture Players in the Motion Picture Story Magazine in May 1913, Almost 11 Years Before Another Non-Caucasian Woman Followed in Her Steps". Presences and Representation of Women in the Early Years of Cinema,1895-1920. Gérone: Fundacio Museu del Cinema.

- Schultz, Marianne (2014). A Harmony of Frenzy: New Zealand Performed on the Stage, Screen and Airwaves, 1862 to 1940 (PDF) (thèse de doctorat en histoire). Auckland: Auckland University.

- Slide, Anthony (1994). Early American Cinema. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press.