Münster

Münster

Mönster (Westphalian) | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 51°57′45″N 07°37′32″E / 51.96250°N 7.62556°E | |

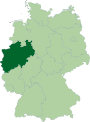

| Country | Germany |

| State | North Rhine-Westphalia |

| Admin. region | Münster |

| District | Urban district |

| Founded | 793 |

| Subdivisions | 6 |

| Government | |

| • Lord mayor (2020–25) | Markus Lewe[1] (CDU) |

| • Governing parties | Greens / SPD / Volt |

| Area | |

| • Total | 302.89 km2 (116.95 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 60 m (200 ft) |

| Population (2023-12-31)[2] | |

| • Total | 322,904 |

| • Density | 1,100/km2 (2,800/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 48143–48167 |

| Dialling codes | 0251 02501 (Hiltrup, Amelsbüren) 02506 (Wolbeck, Angelmodde) 02533 (Nienberge) 02534 (Roxel) 02536 (Albachten) |

| Vehicle registration | MS |

| Website | www.muenster.de |

Münster (German: [ˈmʏnstɐ] ; Westphalian: Mönster) is an independent city (Kreisfreie Stadt) in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is in the northern part of the state and is considered to be the cultural centre of the Westphalia region. It is also a state district capital. Münster was the location of the Anabaptist rebellion during the Protestant Reformation and the site of the signing of the Treaty of Westphalia ending the Thirty Years' War in 1648. Today, it is known as the bicycle capital of Germany.[3]

Münster gained the status of a Großstadt (major city) with more than 100,000 inhabitants in 1915.[4] As of 2014[update], there are 300,000[5] people living in the city, with about 61,500 students,[6] only some of whom are recorded in the official population statistics as having their primary residence in Münster. Münster is a part of the international Euregio region with more than 1,000,000 inhabitants (Enschede, Hengelo, Gronau, Osnabrück).

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]In 793, Charlemagne sent out Ludger as a missionary to evangelise the Münsterland.[7] In 797, Ludger founded a school that later became the Cathedral School.[7] Gymnasium Paulinum traces its history back to this school.[7] Ludger was ordained as the first bishop of Münster.[7] The first cathedral was completed by 850.[7] The combination of ford and crossroad, market place, episcopal administrative centre, library and school, established Münster as an important centre.[8] In 1040, Heinrich III became the first king of Germany to visit Münster.[7]

Middle Ages and early modern period

[edit]In the Middle Ages, the Prince-Bishopric of Münster was a leading member of the Hanseatic League.[7]

In 1534, an apocalyptic Anabaptist sect, led by John of Leiden, took power in the Münster rebellion and founded a democratic proto-socialistic state. They claimed all property, burned all books except the Bible, and called it the "New Jerusalem". John of Leiden believed he would lead the elect from Münster to capture the entire world and purify it of evil with the sword in preparation for the Second Coming of Christ and the beginning of the Millennium. They went so far as to require all citizens to be naked as preparation for the Second Coming. However, the town was recaptured in 1535; the Anabaptists were tortured to death and their corpses were exhibited in metal baskets, which can still be seen hanging from the tower of St. Lambert's Church.[7]

Part of the signing of the Peace of Westphalia of 1648 was held in Münster.[9] This ended the Thirty Years' War and the Eighty Years' War.[9] It also guaranteed the future of the prince-bishop and the diocese; the area was to be exclusively Roman Catholic.

18th, 19th and early 20th centuries

[edit]

The last outstanding palace of the German baroque period, the Schloss Münster, was created according to plans by Johann Conrad Schlaun.[7] The University of Münster (called "Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster", WWU, between 1907 and 2023) was established in 1780. It is now a major European centre for excellence in education and research with large faculties in the arts, humanities, theology, sciences, business and law. Currently there are about 40,000 undergraduate and postgraduate students enrolled.[citation needed] In 1802 Münster was conquered by Prussia during the Napoleonic Wars. It was also part of the Grand Duchy of Berg between 1806 and 1811 and the Lippe department of the First French Empire between 1811 and 1813, before returning to Prussian rule. It became the capital of the Prussian province of Westphalia. In 1899 the city's harbour started operations when the city was linked to the Dortmund-Ems Canal.

World War II

[edit]

In the 1940s the Bishop of Münster, Cardinal Clemens August Graf von Galen, was one of the most prominent critics of the Nazi government. In retaliation for his success (The New York Times described Bishop von Galen as "the most obstinate opponent of the National Socialist anti-Christian program"[10]), Münster was heavily garrisoned during World War II, and five large complexes of barracks are still a feature of the city. Münster was the headquarters (Hauptsitz) for the 6th Military District (Wehrkreis) of the German Wehrmacht, under the command of Infantry General (General der Infanterie) Gerhard Glokke. Originally made up of Westphalia and the Rhineland, after the Battle of France it was expanded to include the Eupen – Malmedy district of Belgium. The headquarters controlled military operations in Münster, Essen, Düsseldorf, Wuppertal, Bielefeld, Coesfeld, Paderborn, Herford, Minden, Detmold, Lingen, Osnabrück, Recklinghausen, Gelsenkirchen, and Cologne.

Münster was the home station for the VI and XXIII Infantry Corps (Armeekorps), as well as the XXXIII and LVI Panzerkorps. Münster was also the home of the 6th, 16th and 25th Panzer Division; the 16th Panzergrenadier Division; and the 6th, 26th, 69th, 86th, 106th, 126th, 196th, 199th, 211th, 227th, 253rd, 254th, 264th, 306th, 326th, 329th, 336th, 371st, 385th, and 716th Infantry Divisions (Infanterie-division).

Münster was the location of the Oflag VI-D prisoner-of-war camp mostly for French, but also some Polish and Soviet officers,[11] and a Nazi prison with several forced labour subcamps in the city and other localities.[12]

A secondary target of the Oil Campaign of World War II, Münster was bombed on 25 October 1944 by 34 diverted B-24 Liberator bombers, during a mission to a nearby primary target, the Scholven/Buer synthetic oil plant at Gelsenkirchen. About 63 per cent of the city including 91 per cent of the Old City was destroyed by Allied air raids.[13] The US 17th Airborne Division, fighting as infantry, attacked Münster with the British 6th Guards Tank Brigade on 2 April 1945 and fought its way into the city centre, which was captured in house-to-house fighting on the following day.[14]

Postwar period

[edit]From 1946 to 1998, there was a Latvian secondary school in Münster,[15] and in 1947, one of the largest of about 93 Latvian libraries in the West was established in Münster.[16] In the 1950s the Old City was rebuilt to match its pre-war state, though many of the surrounding buildings were replaced with cheaper modern structures. It was also for several decades a garrison town for the British forces stationed in West Germany.

Post-reunification

[edit]In 2004, Münster won an honourable distinction: the LivCom-Award for the most livable city in the world with a population between 200,000 and 750,000.[17] Münster is famous and liked for its bicycle friendliness and for the student character of the city that is due to the influence of its university, the University of Münster.[18][19]

Geography

[edit]Geographic position

[edit]

Münster is situated on the river Aa, approximately 15 kilometres (9 miles) south of its confluence with the Ems in the so-called Westphalian Bight, a landscape studded with dispersed settlements and farms – the "Münsterland". The Wolstonian sediments of the mountain ridge called "Münsterländer Kiessandzug" cross the city from north to south. The highest elevation is the Mühlenberg in the northwest of Münster, 97 metres above sea level. The lowest elevation is at the Ems, 44 m above sea level. The city centre is 60 m above sea level, measured at the Prinzipalmarkt in front of the historic city hall.

The Dutch city of Enschede lies about 65 km (40 mi) northwest of Münster. Other major cities nearby include Osnabrück, about 44 km (27 mi) to the north, Dortmund, about 61 km (38 mi) to the south, and Bielefeld, about 62 km (39 mi) to the east.

Münster is one of the 42 agglomeration areas and one of Germany's biggest cities in terms of area. But it includes substantial sparsely-populated rural districts which were formerly separate local government authorities until they were amalgamated in 1975. Thus nearly half the city's area is agricultural, resulting in a low population-density of approximately 900 inhabitants per km2.

Population density

[edit]The city's built-up area is quite extensive. There are no skyscrapers and few high-rise buildings but very many detached houses and mansions. Still the population density reaches about 15,000 inhabitants per km2 in the city centre.[20] Calculating the population density based on the actual populated area results in approximately 2890 inhabitants per km2.[21][verification needed]

Münster's urban area of 302.91 square kilometres (116.95 sq mi) is distributed into 57.54 square kilometres (22.22 sq mi) covered with buildings while 0.99 km2 (0.38 sq mi) are used for maintenance and 25.73 km2 (9.93 sq mi) for traffic areas, 156.61 km2 (60.47 sq mi) for agriculture and recreation, 8.91 km2 (3.44 sq mi) are covered by water, 56.69 km2 (21.89 sq mi) is forested and 6.23 km2 (2.41 sq mi) is used otherwise.[22]: 18 The perimeter has a length of 107 kilometres (66 miles), the largest extend of the urban area in north–south direction is 24.4 km (15.2 mi), in east–west direction 20.6 km (12.8 mi).[23]

Climate

[edit]A well-known saying in Münster is "Entweder es regnet oder es läuten die Glocken. Und wenn beides zusammen fällt, dann ist Sonntag" ("Either it rains or the church bells ring. And if both occur at the same time, it's Sunday."), but in reality the rainfall with approximately 758 mm (29.8 inches) per year is close to the average rainfall in Germany.[24] The perception of Münster as a rain-laden city isn't caused by the absolute amount of rainfall but by the above-average number of rainy days with relatively small amounts of rainfall. The average temperature is 9.4 °C (48.9 °F) with approximately 1500 sun hours per year.[24] Consequently, Münster is in the bottom fifth in comparison with other German cities. The winter in Münster is fairly mild and snowfall is unusual. The temperature during summertime meets the average in Germany. The highest daily rainfall was registered on 28 July 2014: One weather station of the MeteoGroup reported a rainfall of 122.2 L/m2 (2.50 imp gal/sq ft); the State Environment Agency registered at one of its stations 292 L/m2 (6.0 imp gal/sq ft) during seven hours.[25] The record rainfall led to severe flooding throughout the city and the nearby Greven.

| Climate data for Münster (Münster Osnabrück Airport) (1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

6.2 (43.2) |

10.1 (50.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

21.8 (71.2) |

24.2 (75.6) |

23.7 (74.7) |

19.5 (67.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

9.1 (48.4) |

5.8 (42.4) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

3.1 (37.6) |

5.9 (42.6) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

16.6 (61.9) |

18.7 (65.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

14.5 (58.1) |

10.4 (50.7) |

6.3 (43.3) |

3.5 (38.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.9 (35.4) |

4.6 (40.3) |

8.2 (46.8) |

11.2 (52.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.3 (37.9) |

0.9 (33.6) |

6.1 (43.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 64.5 (2.54) |

49.2 (1.94) |

49.6 (1.95) |

40.5 (1.59) |

54.8 (2.16) |

63.4 (2.50) |

73.9 (2.91) |

78.5 (3.09) |

68.7 (2.70) |

63.1 (2.48) |

61.5 (2.42) |

67.8 (2.67) |

735.7 (28.96) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 17.6 | 15.8 | 15.4 | 13.5 | 13.7 | 14.9 | 15.2 | 15.2 | 14.3 | 15.6 | 17.8 | 19.1 | 188.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1.0 cm) | 4.6 | 3.6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 3.3 | 13 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.5 | 82.2 | 76.9 | 69.8 | 69.3 | 71.1 | 71.0 | 73.2 | 79.6 | 83.8 | 87.1 | 87.3 | 78.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 51.6 | 73.3 | 124.2 | 178.4 | 206.7 | 203.2 | 212.3 | 193.3 | 148.2 | 108.8 | 57.1 | 44.2 | 1,597.6 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization[26] | |||||||||||||

Adjacent cities and districts

[edit]Münster borders on the following cities and municipalities, named clockwise and beginning in the northwest: Altenberge and Greven (District of Steinfurt), Telgte, Everswinkel, Sendenhorst and Drensteinfurt (District of Warendorf), as well as Ascheberg, Senden and Havixbeck (District of Coesfeld).

City boroughs

[edit]

The city is divided into six administrative districts or Stadtbezirke: "Mitte" (Middle), "Nord" (North), "Ost" (East), "West", "Süd-Ost" (South-East) and "Hiltrup". Each district is represented by a council of 19 representatives elected in local elections. Heading each council is the district mayor, or Bezirksvorsteher. Every district is subdivided into residential quarters (Wohnbereiche). This official term, however, is not used in common speech, as there are no discrete definitions of the individual quarters. The term "Stadtteil" is used instead, mainly referring to the incorporated communities. The districts are also divided into 45 statistical districts.

The following list names each district with its residential and additional quarters. These are the official names, which partly differ from the usage in common speech.[27]

- Mitte:

- Kernbereich (Centre)

- Nord:

- Münster-Coerde|Coerde

- Kinderhaus

- Sprakel with Sandrup

- Ost:

- West:

- Albachten

- Gievenbeck

- Mecklenbeck

- Nienberge with Häger, Schönebeck and Uhlenbrock

- Roxel with Altenroxel and Oberort

- Sentruper Höhe

- Süd-Ost:

- Angelmodde with Hofkamp

- Gremmendorf with Loddenheide

- Wolbeck

- Hiltrup:

- Amelsbüren with Sudhoff, Loevelingloh and Wilbrenning

- Berg Fidel

- Hiltrup

The centre can be subdivided into historically evolved city districts whose borders are not always strictly defined, such as

- Aaseestadt

- Erphoviertel

- Geistviertel

- Hansaviertel

- Herz-Jesu-Viertel

- Kreuzviertel

- Kuhviertel

- Mauritzviertel

- Neutor

- Pluggendorf

- Rumphorst

- Schlossviertel

- Südviertel

- Uppenberg

- Zentrum Nord

Demographics

[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1816 | 17,316 | — |

| 1831 | 21,893 | +26.4% |

| 1851 | 25,222 | +15.2% |

| 1871 | 24,821 | −1.6% |

| 1900 | 63,754 | +156.9% |

| 1910 | 90,254 | +41.6% |

| 1919 | 100,452 | +11.3% |

| 1925 | 106,418 | +5.9% |

| 1933 | 122,210 | +14.8% |

| 1939 | 141,059 | +15.4% |

| 1950 | 118,889 | −15.7% |

| 1956 | 155,241 | +30.6% |

| 1961 | 182,721 | +17.7% |

| 1966 | 200,376 | +9.7% |

| 1971 | 198,470 | −1.0% |

| 1976 | 266,083 | +34.1% |

| 1981 | 271,810 | +2.2% |

| 1986 | 246,186 | −9.4% |

| 1990 | 259,438 | +5.4% |

| 2001 | 267,197 | +3.0% |

| 2011 | 289,576 | +8.4% |

| 2022 | 303,772 | +4.9% |

| Population size may be affected by changes in administrative divisions. Source:[28][circular reference][29] | ||

Münster has a population of about 320,000 people. It is the 10th largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia and the 20th largest city in Germany. It is also the seventh largest German city by area at 303.28 km2 (117.10 sq mi), and serves as the center of the Münster region (known as Münsterland in German). Considered one of the oldest German cities, Münster has been a major city since approximately 1000 AD. It first reached 100,000 inhabitants in 1948, and the population has continued to grow since the 1980s due to the popularity of the local university. Münster is also known for its bicycles, and some estimates suggest it has more bicycles than people. The city reached a population of 300,000 in 2014.[citation needed]

Number of largest foreign groups in Münster by nationality:[30]

| Rank | Nationality | Population (31 December 2022) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3,478 | |

| 2 | 2,365 | |

| 3 | 1,885 | |

| 4 | 1,735 | |

| 5 | 1,636 | |

| 6 | 1,343 | |

| 7 | 1,105 | |

| 8 | 987 | |

| 9 | 865 | |

| 10 | 738 |

Politics

[edit]

Mayor

[edit]

The current mayor of Münster is Markus Lewe of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), who was elected in 2009 and re-elected in 2015 and 2020. The most recent mayoral election was held on 13 September 2020, with a runoff held on 27 September, and the results were as follows:

| Candidate | Party | First round | Second round | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Markus Lewe | Christian Democratic Union | 68,817 | 44.6 | 69,705 | 52.6 | |

| Peter Todeskino | Alliance 90/The Greens | 43,978 | 28.5 | 62,824 | 47.4 | |

| Michael Jung | Social Democratic Party | 25,170 | 16.3 | |||

| Ulrich Thoden | The Left | 5,200 | 3.4 | |||

| Jörg Berens | Free Democratic Party | 4,685 | 3.0 | |||

| Roland Scholle | Die PARTEI | 2,581 | 1.7 | |||

| Georgios Tsakalidis | Münster List | 1,975 | 1.3 | |||

| Michael Krapp | Ecological Democratic Party | 1,139 | 0.7 | |||

| Sebastian Kroos | Pirate Party Germany | 918 | 0.6 | |||

| Valid votes | 154,463 | 99.3 | 132,529 | 99.5 | ||

| Invalid votes | 1,132 | 0.7 | 636 | 0.5 | ||

| Total | 155,595 | 100.0 | 133,165 | 100.0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 247,189 | 62.9 | 247,097 | 53.9 | ||

| Source: State Returning Officer | ||||||

City council

[edit]

The Münster city council governs the city alongside the mayor. The most recent city council election was held on 13 September 2020, and the results were as follows:

| Party | Votes | % | +/- | Seats | +/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democratic Union (CDU) | 50,465 | 32.7 | 22 | |||

| Alliance 90/The Greens (Grüne) | 46,696 | 30.3 | 20 | |||

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | 27,163 | 17.6 | 12 | |||

| The Left (Die Linke) | 7,539 | 4.9 | 3 | |||

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | 7,104 | 4.6 | 3 | |||

| Volt Germany (Volt) | 4,032 | 2.6 | New | 2 | New | |

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | 3,399 | 2.2 | 1 | |||

| Die PARTEI (PARTEI) | 3,196 | 2.1 | New | 1 | New | |

| Ecological Democratic Party (ÖDP) | 1,876 | 1.2 | 1 | ±0 | ||

| Munster List (Münsterliste) | 1,848 | 1.2 | New | 1 | New | |

| Pirate Party Germany (Piraten) | 959 | 0.6 | 0 | |||

| Modern Social Party (MSP) | 71 | 0.0 | New | 0 | New | |

| Valid votes | 154,348 | 99.2 | ||||

| Invalid votes | 1,273 | 0.8 | ||||

| Total | 155,621 | 100.0 | 66 | |||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 247,189 | 63.0 | ||||

| Source: State Returning Officer | ||||||

Representation

[edit]Münster forms its own Electoral district (No. 129) for elections on a national level. Due to Germany's mixture of a direct and a proportional electoral system Münster sends a directly elected member into the Bundestag as well as other politicians have the chance to qualify via their party's state-wide list. As for the 2021 German federal election health politician Maria Klein-Schmeink (The Greens) won the districts seat in the Bundestag with 32.3% of the personal vote.[31] Defeated candidates, former member of the Landtag of North Rhine-Westphalia[32] Stefan Nacke (CDU/26.2%)[31] and former environment minister Svenja Schulze (SPD/24.1%) both became members of the 20th Bundestag via their parties' lists.[33] Svenja Schulze entered the new Scholz cabinet regaining a position as minister, this time in the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development.[34]

On the state level Münster was divided into two constituencies up until the 2017 North Rhine-Westphalia state election. The election system of state elections mirrors that of national elections. During the legislative period of Laschet cabinet redistricting resulted in Münster now being split up into three constituencies, two of which now also include some surrounding municipalities. The 2017 election saw both CDU candidates Stefan Nacke and Simone Wendland winning their seat via the constituency.[35] Via party lists Svenja Schulze (SPD) and Josefine Paul (The Greens) entered the Landtag.[36] After Nacke and Schulze both changed into federal politics, Münster is left with only two representatives in the Landtag.

Economy

[edit]Greater Münster is home to many industries such as those of public authorities, consulting companies, insurance companies, banks, computer centres, publishing houses, advertising and design.[37] The service sector has created several thousand jobs.[37] Retailers have approximately 1.9 billion euro turnover.[37] The city still has traditional merchants' townhouses as well as modern outlets.[37]

Entrepreneurship

[edit]Münster's wealth was underpinned by wealthy merchant families such as the Merfelders, Rüschkamps, and Berens. Berens Bank was founded in 1630 in Münster, Germany, by Hermann Berens. Berens was a successful merchant and banker, and he founded the bank to provide financial services to other businesses and individuals in the city. The Berens family lived in a large house on Roggenmarkt, known as the Berenshof. The Berens interests inclused textiles and grain.

The job market situation in Münster is "comparatively good".[38] Of the approximately 130,000 employees subject to social insurance contribution more than 80% work in the tertiary sector, about 17% work in the secondary sector and 1% work in the primary sector.[22]: 95

Main sights

[edit]

("Villa Kunterbunt")

- St. Paul's Cathedral, built in the 13th century in a mixture of late Romanesque and early Gothic styles. It was completely restored after World War II. It includes an astronomical clock of 1540, adorned with hand-painted zodiac symbols, which traces the movement of the planets, and plays a Glockenspiel tune every noon.

- The Prinzipalmarkt, the main shopping street in the city centre with the Gothic city hall (14th century) in which the Peace of Westphalia treaty which put an end to the Thirty Years' War was signed in 1648. Immediately north of the Prinzipalmarkt is the Roggenmarkt.

- St Lambert's Church (1375), with three cages hanging from its tower above the clock face. In 1535 these cages were used to display the corpses of Jan van Leiden and other leaders of the Münster Rebellion, who promoted polygamy and renunciation of all property.

- Überwasserkirche, a Gothic hall church consecrated in 1340 as church of a Stift which grew to be the University of Münster

- The Schloss (palace), built in 1767–87 as residence for the prince-bishops by the Baroque architect Johann Conrad Schlaun and Wilhelm Ferdinand Lipper. Now the administrative centre for the University.

- The Botanischer Garten Münster, a botanical garden founded in 1803

- The Zwinger fortress built in 1528. Used from the 18th to the 20th century as a prison. During World War II, the Gestapo also used the Zwinger for executions

- "Krameramtshaus" (1589), an old guild house, which housed the delegation from the Netherlands during the signing of the Peace of Westphalia

- Stadthaus (1773)

- Haus Rüschhaus (1743–49), a country estate situated in Nienberge, built by Johann Conrad Schlaun for himself

- Erbdrostenhof (1749–53), a Baroque palace, also built by Schlaun, residence of Droste zu Vischering noble family and birthplace of Blessed Mary of the Divine Heart.

- Clemenskirche (1745–53), a Baroque church, also built by Schlaun

- Kreuzkirche, a Gothic-revival church

- Signal-Iduna Building (1961), the first high-rise building in Münster

- LVM-Building, high-rise building near the Aasee

- LBS-Building, location of Münster's first zoo. Some old structures of the former zoo can be found in the park around the office building. Also the "Tuckesburg", the strange-looking house of the zoo's founder, is still intact.

- "Münster Arkaden" (2006), new shopping centre between Prinzipalmarkt and the Pablo Picasso Museum of Graphic Art

- "Cavete", the oldest academic pub in Münster

- Westphalian State Museum of Art and Cultural History

- University Bible museum

- Buddenturm – a former city water tower built about 1150 as a defence tower and now fitted with windows, is near the largest aggregation of pubs in the city

- City Museum ("Stadtmuseum"), exhibition of a large collection showing the political and cultural history of the city from its beginning up to present, housed by a converted former department store

- University Mineralogical Museum

- Westphalian Horse Museum ("Hippomax")

- Mühlenhof open-air museum, depicting a typical Westphalian village as it looked centuries ago

- Westphalian Museum for Natural History, state museum and planetarium

- Museum of Lacquer Art (founded and operated by the company BASF Coatings)

- Pablo Picasso Museum of Graphic Art, the only museum devoted exclusively to the graphic works of Pablo Picasso

- Pinkus Müller, the only brewery left in Münster; originally there were more than 150.

- Kiepenkerl Statue in Kiepenkerl Square

Education

[edit]Münster is home to many institutions of higher education, including the University of Münster and University of Applied Sciences. The city also has 92 primary and secondary education schools. The city had 61,441 students in 2015/16.[39]

Transport

[edit]

Air

[edit]Münster Osnabrück Airport serves the city of Münster. The airport provides flights to European destinations mostly.

Bicycling

[edit]Münster claims to be the bicycle capital of Germany.[40] It states that in 2007, vehicle traffic (36.4%) fell below traffic by bicycle (37.6%),[41] even though it is unclear how such a figure is defined. The city maintains an extensive network for bicycles including the popular "Promenade" which encircles Münster's city centre. While motorised vehicles are banned, there are paths for pedestrians. Additional bicycle paths link all city districts with the inner city and special traffic lights provide signals for bicyclists.[41] Bicycle stations in Münster offer bicycle rentals.[41]

Train

[edit]Münster's Central Station is on the Wanne-Eickel–Hamburg railway. The city is connected by Intercity trains to many other major cities in Germany.

Public transport

[edit]Historically, Münster had a historic tramway system, but it closed in 1954. Today, Münster does have some public transportation, which includes bus expresses,[42] sightseeing buses,[43] "waterbuses",[44] Lime scooters[45] and bicycle rentals.[41] It is the largest German city without a U-Bahn or an S-Bahn system.

Sports

[edit]The city is home to Preußen Münster, which was founded on 30 April 1906. The main section is football, and the team plays at Preußenstadion. Other important sports teams include the USC Münster e.V. volleyball club.

Uni Baskets Münster is the city's professional basketball team.[46] Home games are at Sporthalle Berg Fidel.

British forces

[edit]After the Second World War, Münster became a major station within Osnabrück Garrison, part of British Forces Germany. Their presence was gradually reduced, yet there are still many active military bases. The last forces left Münster on 4 July 2013.[47]

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit] York, England, United Kingdom (1958)

York, England, United Kingdom (1958) Orléans, France (1960)

Orléans, France (1960) Kristiansand, Norway (1967)

Kristiansand, Norway (1967) Monastir, Tunisia (1969)

Monastir, Tunisia (1969) Rishon LeZion, Israel (1981)

Rishon LeZion, Israel (1981) Fresno, United States (1986)

Fresno, United States (1986) Ryazan, Russia (1989)

Ryazan, Russia (1989) Mühlhausen, Germany (1990)

Mühlhausen, Germany (1990) Lublin, Poland (1991)

Lublin, Poland (1991) Enschede, Netherlands (2020)[49]

Enschede, Netherlands (2020)[49]

Notable people

[edit]

- Johannes Veghe (c. 1435–1504), religious writer

- Henry Nicholis (ca.1501 – ca.1580), a German mystic, founded Familia Caritatis.[50]

- Christoph Bernhard Verspoell (1743–1818), priest and publisher of an influential hymnal

- Clemens August Droste zu Vischering (1773–1845), Archbishop of Cologne.[51]

- Georges Depping (1784–1853), German-French historian

- Annette von Droste-Hülshoff (1797–1848), noble and poet.[52]

- Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler (1811–1877), theologian and politician, Bishop of Mainz.[53]

- Paul Melchers (1813–1895), Cardinal and Archbishop of Cologne

- Joseph Weydemeyer (1818–1866), military officer, journalist, politician and Marxist revolutionary

- Ludwig von Wittich (1818–1884), Prussian lieutenant general

- Max von Forckenbeck (1821–1892), National Liberal politician, mayor of Wroclaw and Berlin

- Bernard Altum (1824–1900), zoologist, ornithologist and forest scientist

- Elisabet Ney (1833–1907), sculptor

- Alexander von Kluck (1846–1934), German general, World War I

- Albert Kopfermann (1846–1914), musicologist and librarian

- Mary of the Divine Heart Droste zu Vischering (1863–1899), noble and nun beatified by Pope Paul VI

- Carl Schuhmann (1869–1946), gymnast and wrestler

- Alfred Flechtheim (1878–1937), art dealer, art collector, journalist, and publisher

- Clemens August Graf von Galen (1878–1946), cardinal, Bishop of Münster, beatified by Pope Benedict XVI

- Friedrich-Carl Rabe von Pappenheim (1894–1977), general in the Wehrmacht of Nazi Germany and war criminal

- Kurt Gerstein (1905–1945), SS officer

- Gunther Plaut (1912–2012), Reform rabbi and author

- Moondog (1916–1999), musician, composer, theoretician, poet, and inventor of musical instruments

- Alfred Dregger (1920–2002), politician and leader of the CDU

- Peter Duesberg (born 1936), virologist who discovered the first retrovirus

- Dieter Sieger (born 1938), shipbuilder

- Heinz Lukas-Kindermann (born 1939), opera director

- Detlev Jöcker (born 1951), composer, singer and songwriter

- Götz Alsmann (born 1957), television presenter, musician, and singer

- Andreas Dombret (born 1960), board member of German central bank Deutsche Bundesbank

- Monika Grütters (born 1962), politician

- Ute Lemper (born 1963), cabaret singer and actress

- Stefan Dohr (born 1965), French horn player, current principal horn of the Berlin Philharmonic

- Günther Jauch (born 13 July 1965) entertainer, journalist, and tv moderator

- Tanita Tikaram (born 1969), British singer-songwriter

- Berthold Warnecke (born 1971), dramaturge and opera director

- Franka Potente (born 1974), German actress

- Guido Maria Kretschmer (Born 11 May 1975), designer and tv moderator

- Linus Gerdemann (born 1982), cyclist

- Jens Höing (born 1987), racing driver

- Esther Dierkes (born 1990), opera singer

Gallery

[edit]-

Symbolic sword, old city hall

-

Hauptbahnhof, Centre

-

Entrance bicycle station opposite the old railway station

-

Promenade in autumn

-

Marienplatz Münster Centre

-

Old Apollo cinema, Marienplatz

-

Münster's municipal theatre

-

Public Library, Centre

-

Landesmuseum Münster

-

LVA (State Social Insurance Board) Münster-Nord

-

Trade Fair Centre Münster

See also

[edit]- Munster, Lower Saxony

- Munster Province, Republic of Ireland

- CeNTech

- Fernmeldeturm

- Muenster, Texas, U.S.

- H-Blockx

- Minster, Ohio, U.S.

References

[edit]- ^ Wahlergebnisse in NRW Kommunalwahlen 2020, Land Nordrhein-Westfalen, accessed 19 June 2021.

- ^ "Bevölkerung der Gemeinden Nordrhein-Westfalens am 31. Dezember 2023 – Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes auf Basis des Zensus vom 9. Mai 2011" (in German). Landesbetrieb Information und Technik NRW. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ "Münster bicycle capital". wwf.panda.org. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ "1900 to 1945". Stadt Münster. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Martin Kalitschke (11 October 2014). "Jetzt hat Münster 300 000 Einwohner" [Now Münster has 300 000 inhabitants]. Westfälische Nachrichten (in German). Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ Klaus Baumeister (24 January 2017). "Ohne Hochschulen geht es bergab – Studenten machen Münster groß" [Without universities it's going downhill – University students make Münster large]. Westfälische Nachrichten (in German). Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "793 to 1800". Stadt Münster. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Vita des heiligen Liudgers" [Resume of the holy Liudgers]. Kirchensite.de (in German). Archived from the original on 10 January 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

- ^ a b "A foray into town history". Stadt Münster. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "The Lion of Münster and Pius XII". 30Days. Archived from the original on 19 October 2007. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Overmans, Rüdiger; Vogt, Wolfgang (2022). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume IV. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-253-06089-1.

- ^ "Zuchthaus Münster". Bundesarchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ Ian L. Hawkins (1999). The Munster Raid: Before and After. FNP Military Division. ISBN 978-0917678493.

- ^ Stanton, Shelby (2006). World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division, 1939–1946. Stackpole Books. p. 97.

- ^ Ebdene, Aija (9 February 2005). "Greetings to all users of the Guide worldwide from the Latvian Community in Germany (LKV)" (PDF). A Guide for Latvians Abroad. LKV. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ^ Smith, Inese; Štrāle, Aina (July 2006). "Witnessing and Preserving Latvian Culture in Exile: Latvian Libraries in the West". Library History, Volume 22, Number 2 – pp. 123–135(13). Maney Publishing. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ^ "LivCom website, page for 2004 awards". livcomawards.com. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ^ "With history into the future" (PDF). Stadt Münster. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2011.

- ^ 10-minute DivX coded film: the 48mb-version or the 87mb-version from the official Münster-homepage.

- ^ Amt für Stadtentwicklung, Stadtplanung, Verkehrsplanung. "Map of population density in the statistical areas" (PDF). Stadt Münster.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)[permanent dead link], page 2 - ^ Regional statistics for NRW of Landesamt für Datenverarbeitung und Statistik Nordrhein-Westfalen

- ^ a b "Jahres-Statistik 2006 Stadt Münster" [Yearly statistics 2006 City of Münster] (PDF) (in German). City of Münster. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2008.

- ^ "Von Aasee bis Zwinger – ein kleines Glossar" [From Aasee to Zwinger – a small glossary] (in German). Stadt Münster. Archived from the original on 4 May 2008.

- ^ a b "Klima in Münster". kli. 21 February 2006. Archived from the original on 6 May 2006. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ^ "Unwetterlage Deutschland Ende Juli 2014 – Extremregen in Münster". Unwetterzentral. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 12 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "Hauptsatzung der Stadt Münster vom 21.12.1995" [Main constitution of the city of Münster on 21 December 1995] (PDF) (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2008.

- ^ Link

- ^ "Germany: States and Major Cities".

- ^ "Jahres-Statistik 2016 – Bevölkerung" (PDF). Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ a b "Ergebnisse Münster – Der Bundeswahlleiter". www.bundeswahlleiter.de. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ vCardvCard (19 July 2021). "Dr. Stefan Nacke". CDU Nordrhein-Westfalen (in German). Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ "Gewählte in Landeslisten der Parteien in Nordrhein-Westfalen – Der Bundeswahlleiter". www.bundeswahlleiter.de. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ "Svenja Schulze". Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung (in German). Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ "Landtagswahl 2017". www.stadt-muenster.de. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ "Landtagswahl 2017 in NRW". www.wahlergebnisse.nrw. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Economic location". Stadt Münster. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ "Job market". Stadt Münster. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Münster – Data and Facts" (PDF). Stadt Münster. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ "Bicycling Münster". Stadt Münster. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Bicycles". Stadt Münster. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ "How to travel by bus: some helpful tips" (PDF). Stadtwerke Münster. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ "Stadtrundfahrten in Münster" [City tours in Münster]. Der Münster Bus (in German). Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ "Das KombiTicket-WasserBus SOLAARIS – Ihre Vorteile auf einen Blick" [The KombiTicket water bus SOLAARIS – Your benefits at a glance]. Stadtwerke Münster (in German). Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ "Lime Locations | Bring Lime Scooters and Bikes to Your City or University". www.li.me.

- ^ „An dieser Brücke festhalten“: Neuer Name der Baskets ist bekannt Henner Henning (muensterschezeitung.de), 19 June 2023. Accessed 10 July 2023.(in German)

- ^ "Abzug britischer Streitkräfte: Prinz Andrew verabschiedet die letzten Soldaten aus Münster" [Withdrawal of British forces: Prince Andrew bids farewell to the last soldiers from Münster]. Westfalen heute (in German). 11 June 2013. Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ "Städtepartnerschaften". stadt-muenster.de (in German). Münster. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ "Städtepartnerschaft Münster – Enschede ist offiziell". stadt-muenster.de (in German). Münster. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ Pollard, Albert Frederick (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). p. 656.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 591.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 591.

- ^ Lias, John James (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). p. 763.

External links

[edit]- Official website

(in German)

(in German) - English page of Münster All-Weather Zoo (in English)

- Münster Zoo at Zoo-Infos.de (in English)

- Muenster City Panoramas – Panoramic Views of Münster's Highlights (in German)

- 7Grad.org – Bunkers in Muenster – History of Muenster's air raid shelters (in German)

- The Siege of Muenster – audio discussion from "In Our Time" BBC

- Technology Park Münster (Host of technology companies in Münster) (in English)

- Tourist-Info (in English)

- Münster Events (in German)

- Münster Notgeld (emergency banknotes) depicting the Münster Rebellion with Ian Bockelson, Berndt Knipperdollink, Berntken Krechting, and Jan van Leyden. http://webgerman.com/Notgeld/Directory/M/Muenster.htm

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Münster". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "Münster (Westphalia)". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Münster". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (9th ed.). 1884.