Máel Coluim (son of the king of the Cumbrians)

| Máel Coluim | |

|---|---|

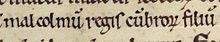

Máel Coluim's name as it appears on folio 13v of British Library Cotton Faustina B IX (the Chronicle of Melrose): "Malcolmum".[1] | |

| Father | possibly Owain Foel |

Máel Coluim (fl. 1054) was an eleventh-century magnate who seems to have been established as either King of Alba or King of Strathclyde. In 1055, Siward, Earl of Northumbria defeated Mac Bethad mac Findlaích, the reigning ruler of the Kingdom of Alba. As a result of this military success against the Scots, several sources assert that Siward established Máel Coluim as king. It is uncertain whether this concerned the kingship of Alba or the kingship of Strathclyde.

The fact that Máel Coluim is described as the son of a "King of the Cumbrians" suggests that he was a member of the Cumbrian royal dynasty of Strathclyde, and could indicate that he was a close relative of Owain Foel, King of Strathclyde, the last known King of Strathclyde. Máel Coluim's Gaelic personal name could indicate that he was maternally descended from the royal Alpínid dynasty of Alba, which would have in turn endowed him with a claim to the Scottish throne.

Máel Coluim's fate is unknown. The fact that Siward died in 1055, and Mac Bethad retained authority in Alba, suggests that Máel Coluim was quickly overcome. There is evidence indicating that the southern reaches of the Kingdom of Strathclyde—the territories upon the Solway Plain—fell into the hands of the English during Siward's floruit. The more northerly lands of the realm seem to have been conquered by Máel Coluim mac Donnchada, King of Alba sometime between 1058 and 1070, and it is uncertain whether an independent Kingdom of Strathclyde still existed by the time of this conquest. In any event, Máel Coluim appears to be the last member of the Cumbrian royal dynasty on record.

Background

[edit]| Simplified pedigree of the Cumbrian royal dynasty. Máel Coluim is highlighted. It is possible that all these men ruled the Kingdom of Strathclyde. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Máel Coluim seems to have been a member of the Cumbrian royal dynasty that ruled the Kingdom of Strathclyde.[2] The twelfth-century Chronicon ex chronicis identifies him as a "son of the king of the Cumbrians" (regis Cumbrorum filium).[3] He was likely closely related to—and possibly descended from—Owain Foel, King of Strathclyde,[4] a monarch attested in 1018 assisting the Scots against the Northumbrians at the Battle of Carham.[5] Not only is the fate of Owain Foel uncertain following this Scottish victory, so too is the fate of the Cumbrian kingdom.[6]

Son of the king of the Cumbrians

[edit]

In 1054, the Kingdom of Alba was invaded by Siward, Earl of Northumbria in an campaign noted by the ninth- to twelfth-century Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.[8][note 1] According to the twelfth-century Gesta regum Anglorum,[11] and Chronicon ex chronicis, Siward set up Máel Coluim in opposition to Mac Bethad mac Findlaích, King of Alba.[12][note 2]

One possible interpretation of these sources is that this Máel Coluim refers to Mac Bethad's opponent Máel Coluim mac Donnchada,[14] a man who reigned as King of Alba from 1058 to 1093. If correct, the episode would seem to be evidence that the latter's father, Donnchad ua Maíl Choluim—a man who had reigned as King of Alba from 1034 to 1040—had once been King of Strathclyde as well.[15]

Against this hypothetical succession is the fact that it rests solely upon Chronicon ex chronicis and Gesta regum Anglorum.[15] In fact, there is otherwise no evidence that Donnchad was ever a Cumbrian king.[16] If Chronicon ex chronicis and Gesta regum Anglorum truly refer to Donnchad's son, it is unclear why these sources describe this man as aon of a mere Cumbrian king as opposed to that of a Scottish king—which Donnchad most certainly was—or why they fail to simply identify him as a son of Donnchad himself.[17] In fact, there is otherwise no firm evidence that Máel Coluim mac Donnchada was in Alba or Northumbria in 1054, or that he had any connection with Siward's victory over Mac Bethad.[18] Mac Bethad seems to have held onto the Scottish kingship until 1057, only to be succeeded by Lulach mac Gilla Comgáin.[19][note 3]

In fact, the events of 1054 more likely refer to Máel Coluim. Rather than being a member of the royal Alpínid dynasty of Alba, Máel Coluim is more likely to have been a member of the Cumbrian royal family.[2] He could have been a son,[23] or grandson of Owain Foel himself.[24] Certainly, a previous member of the family is known to have borne the same name.[25][note 4] If Máel Coluim was indeed a member of this kindred, one possibility is that the Scots had deprived him of the Cumbrian kingship following Owain Foel's demise, and that Siward installed Máel Coluim as king over the Cumbrians following the English victory against Mac Bethad.[27] Another possibility,[28] suggested by the account of events given by both Chronicon ex chronicis[29] and Gesta regum Anglorum, is that Siward installed Máel Coluim as King of Alba.[30] Certainly, Máel Coluim's name could be evidence of an ancestral link with the ruling Alpínids[31]—perhaps even a matrilineal link to Owain Foel's confederate at Carham, Máel Coluim mac Cináeda, King of Alba.[32] If Máel Coluim was indeed a maternal grandson of a Scottish king, he would have certainly possessed a claim to the Scottish throne.[6] Although nothing is known of Máel Coluim's possible reign in Alba, there is reason to suspect that he would have probably functioned as an English puppet, with little support from the Scottish aristocracy.[26]

Although the accounts of 1054 given by both Chronicon ex chronicis and Gesta regum Anglorum can be interpreted as entries about events concerning Máel Coluim,[34] there is a possibility that the compilers of these sources mistakenly assumed that they were actually referring to Máel Coluim mac Donnchada, since the latter's son, David, possessed Cumbria as a principality in the early twelfth century.[35] Nevertheless, there is evidence indicating that the composer of Gesta regum Anglorum was aware that Máel Coluim was not identical to his Scottish namesake.[36] For instance, this source clearly differentiates between the Scottish and Cumbrian kings that assembled with their English counterpart at Chester in 973.[37] The monks of Melrose Abbey, who compiled the twelfth- to thirteenth-century Chronicle of Melrose, also seem to have been aware of Cumbria's geopolitical history, as evinced by the recognisance of the Cumbrian kingdom by the twelfth-century Vita sancti Kentegerni, a work commissioned by Jocelin, Abbot of Melrose.[38]

The first phase in the composition of the Chronicle of Melrose dates to 1173×1174.[40] It was at this point that the chronicle's account of Siward's invasion was compiled from the twelfth-century Historia regum Anglorum.[41] Since the latter source observes that Máel Coluim mac Donnchada unlawfully held Cumbria by force in 1070, the Melrose scribe appears to have been aware that this king was not identical to the Cumbrian Máel Coluim.[42] This may in turn explain why the scribe did not copy over the clause "son of the king of the Cumbrians" from Historia regum Anglorum. The Chronicle of Melrose may therefore be the earliest source to explicitly associate Máel Coluim mac Donnchada with the events of 1054.[43] As a result of this identification, this Scottish monarch was portrayed as a man who only possessed his throne on account of English assistance.[44]

The catalyst behind the monks' misrepresentation of Siward's invasion appears to have been an English revolt dating to 1173 and 1174, when the reigning King of Scotland—a great-grandson of Máel Coluim mac Donnchada—backed a failed rebellion against the King of England.[45] As a result of this Scottish monarch's capture in the course of the uprising, English lordship over Scotland was conceded by the Scots, with conclusion of the Treaty of Falaise in 1174.[46] The conditions imposed upon the Scots date to the very time the scribe compiled his account of 1054, and it is possible these concessions inspired the Melrose monks to concoct an eleventh-century royal precedent for twelfth-century Scottish subservience.[47][note 5]

Disintegration of the Cumbrian realm

[edit]

It is uncertain if the Kingdom of Strathclyde even existed by the time of the events of 1054.[6] There is evidence to suggest that Siward and the Northumbrians exerted a significant amount of influence over the Cumbrian realm by the mid eleventh century.[54] For example, the twelfth-century Historia ecclesiae Eboracensis records that two Bishops of Glasgow—a certain Johannes and Magsuen, whose names could be evidence that they were Cumbrians—were consecrated by Cynesige, Archbishop of York.[55] Although it is uncertain if Glasgow was indeed a diocesan seat in the eleventh century,[56] the fact that an eleventh-century stone cross, decorated in the Northumbrian style, has been recovered from the site of the Glasgow Cathedral, suggests that this site was increasing in importance before the construction of the cathedral in the twelfth century.[57] This cross may, therefore, corroborate the consecrational claims of Historia ecclesiae Eboracensis,[58] which could in turn indicate that Siward and (the senior Northumbrian cleric) Cynesige were indeed exerting influence over the Cumbrians.[59][note 6] Another piece of evidence for Northumbrian expansion is a particular eleventh-century charter detailing the grant of certain rights and lands from a certain Gospatric to several individuals.[62] According to this contract, the grantees received various lands in what came to form the English county of Cumberland, and they also gained a guarantee of protection from Gospatric and Siward.[63][note 7] The likelihood that Siward would have only granted territories within his own sphere of influence, coupled with the fact that the charter specifically states that the granted lands were "once Cumbrian", suggests that most (if not all) of the Cumbrian territories south of the Solway Firth had been gained by Siward sometimes before his death in 1055.[69]

It may have been in the course of Siward's campaign against the Scots that the English gained control of the Solway Plain.[58] Pressure from external forces north of the Solway Firth—such as the contemporaneous expansion of the Gall Gaidheil—could have meant that the Cumbrian leadership allowed the southerly territories fall under Siward's authority.[6] Whilst these lands indeed seem to have fallen under English authority in the eleventh century, the more northerly Cumbrian territories appear to have been conquered by the Scots. In 1070, for example, Gospatric, Earl of Northumbria is recorded to have led an invasion into Scottish-controlled territory in an effort to counter certain devastating Scottish raids into England. According to Historia regum Anglorum, Gospatric directed his counter-strike into Cumbreland, the former lands of the Cumbrian realm. In fact, this source alleges that Máel Coluim mac Donnchada's royal authority in these lands was unlawful since the Scots had only seized the lands "through violent subjugation".[71]

Whilst the record of bishops Johannes and Magsuen seems to reveal that the Cumbrians were independent of the Scots during Cynesige's episcopacy (1055–1060)[72]—albeit possibly under Northumbrian domination[73]—the evidence from Historia regum Anglorum reveals that the northernmost portion of the Cumbrian realm had fallen to the Scots by the time of Gospatric's invasion.[72] Although the events noted by Historia regum Anglorum are corroborated by the twelfth century Historia post Bedam,[74] the Scottish conquest is unrecorded.[75] Nevertheless, the takeover seems to have occurred at some point between Máel Coluim mac Donnchada's accession in 1058 and Gospatric's invasion of 1070.[76] One possibility is that the Scots overthrew the father of the Cumbrian Máel Coluim.[6] Another is that Máel Coluim and his dynasty were overcome in the power vacuum left by Siward's demise in 1055.[77] The fact that Historia regum Anglorum questions the legitimacy of Máel Coluim mac Donnchada's possession of Cumbreland could reveal that the compiler of this source regarded the region as rightfully Northumbrian.[6] In any case, Máel Coluim appears to be the last known member of the Cumbrian dynasty.[78]

See also

[edit]- David, Prince of the Cumbrians, a twelfth-century magnate who bore the titles "prince of the Cumbrians" and "prince of the Cumbrian region", according him quasi-regal status over territories that formerly comprised the Kingdom of Strathclyde.[79]

Notes

[edit]- ^ According to the "D" version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a son and a nephew of Siward were slain in the invasion.[9] This source is partly corroborated by Historia Anglorum, which states that Siward sent a son to conquer Scotland, and that this son was slain there.[10]

- ^ According to the thirteenth-century Gesta antecessorum comitis Waldevi, Siward supported the cause of a deposed king called "Duvenal".[13]

- ^ Gesta regum Anglorum erroneously claims that Siward slew Mac Bethad and installed Máel Coluim as king in his place.[20] The twelfth-century Annales Lindisfarnenses et Dunelmenses, relates that Siward inserted a king in Mac Bethad's place before the latter was able to regain control.[21]

- ^ The Gaelic personal name Máel Coluim means "servant of St Columba". This name was earlier borne by Máel Coluim, King of Strathclyde, son of Dyfnwal ab Owain, King of Strathclyde. Both men could have been ancestors of Máel Coluim.[26]

- ^ Later, in the thirteenth century, probably in 1246×1259, another scribe modified the Chronicle of Melrose in an apparent attempt to salvage Máel Coluim mac Donnchada's legitimacy to the throne.[48] Although the scribe did not amend the chronicle's skewed account of Siward's 1054 campaign, he made several changes in the earlier and latter passages. For instance, the scribe tweaked the 1039 entry concerning Donnchad's death, to label Mac Bethad's succession as a usurpation;[49] he amended the 1055 notice of Lulach's reign to limit it to specifically four and a half months;[50] and he added the statement that Máel Coluim mac Donnchada received the kingship in 1056 because of his "hereditary right".[51] As a result of these thirteenth-century alterations, the Chronicle of Melrose portrayed the latter as a legitimate Scottish sovereign who had no need for English intervention.[52]

- ^ Although Historia ecclesiae Eboracensis describes Johannes and Magsuen as bishops of Glasgow, it is possible that this is an anachronism for "bishop of Cumbria".[60] If the Cumbrian ecclesiastical centre was not located at Glasgow, it could have been seated at Govan or some place else.[61]

- ^ The contract is sometimes called "Gospatric's writ",[64] "Gospatrick's Writ",[65] or "Gospatrick's Writ".[66] It survives in a thirteenth-century copy of the original.[67] The remarkably varied personal names and terminology recorded throughout the document (those with Cumbrian, Scandinavian, Gaelic, and English elements) partly exemplifies the hybrid culture of the region.[68]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Anderson (1922) p. 593; Stevenson (1856) p. 112; Stevenson (1835) p. 51; Cotton MS Faustina B IX (n.d.).

- ^ a b McGuigan (2015b) p. 100; Clarkson (2014) ch. 9; Edmonds (2014) p. 209; Clarkson (2013); Clarkson (2010) chs. genealogical tables, 9; Davies (2009) p. 78; Woolf (2007) p. 262; Clancy (2006); Taylor, S (2006) p. 26; Broun (2004c) pp. 133–135; Duncan (2002) p. 41.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) p. 57; McGuigan (2015b) p. 100; Clarkson (2014) ch. 9, 9 n. 12.

- ^ Taylor, A (2016) p. 10; Clarkson (2014) ch. 9; Edmonds (2014) p. 209; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9; Woolf (2007) p. 262; Taylor, S (2006) p. 26; Broun (2004c) pp. 133–135; Clancy (2006); Duncan (2002) p. 41.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 8, 8 n. 14; Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 573; Woolf (2010) p. 235; Woolf (2007) p. 236; Clancy (2006); Broun (2004c) p. 128; Duncan (1976) p. 21; Anderson (1908) p. 82; Arnold (1885) pp. 155–156 ch. 130; Stevenson (1855) p. 527.

- ^ a b c d e f Clarkson (2014) ch. 9.

- ^ Anderson (1908) p. 85 n. 4; Forester (1854) p. 156; Stevenson (1853) p. 286; Thorpe (1848) p. 212; Corpus Christi College MS. 157 (n.d.).

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) pp. 57–58; Clarkson (2014) ch. 9 ¶¶ 11–12; Parker, E (2014) p. 482; Clarkson (2013); Parker, EC (2012) p. 83, 83 n. 210; Douglas; Greenway (2007) pp. 127–128; Swanton (1998) pp. 184–185; Anderson (1908) pp. 85–86, 85 n. 1; Thorpe (1861) p. 322.

- ^ Parker, EC (2012) p. 83, 83 n. 210; Swanton (1998) p. 185; Anderson (1908) pp. 85–86; Thorpe (1861) p. 322.

- ^ Parker, EC (2012) pp. 83–84; Anderson (1908) p. 85 n. 4; Arnold (1879) p. 194 bk. 6 ch. 22; Forester (1853) p. 204 bk. 6 ch. 22.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) pp. 9–10, 57; McGuigan (2015a) p. 138; Clarkson (2013); Davies (2009) p. 78; Edmonds (2009) p. 53; Woolf (2007) pp. 261–262; Duncan (2002) p. 40; Anderson (1908) p. 85 n. 4; Giles (1847) p. 214 bk. 2 ch. 13; Hardy (1840) p. 330 bk. 2 ch. 196.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) pp. 9–10, 57; McGuigan (2015a) p. 138; McGuigan (2015b) p. 100; Clarkson (2014) ch. 9, 9 n. 12; Clarkson (2013); Clarkson (2010) ch. 9; Gazzoli (2010) p. 71; Davies (2009) p. 78; Edmonds (2009) p. 53; Woolf (2007) p. 261; Swanton (1998) p. 185 n. 17; Broun (2004c) pp. 133–134; Anderson (1908) p. 85 n. 4; Forester (1854) p. 156; Stevenson (1853) p. 286; Thorpe (1848) p. 212.

- ^ Parker, EC (2012) pp. 82–83; Michel (1836) p. 109.

- ^ Edmonds (2009) p. 53; Broun (2004c) pp. 133–134.

- ^ a b Broun (2004c) pp. 133–134.

- ^ McGuigan (2015a) p. 163; Gazzoli (2010) p. 71; Edmonds (2009) p. 53; Broun (2004a); Broun (2004c) pp. 133–134.

- ^ McGuigan (2015a) pp. 138–139; Clarkson (2014) ch. 9; Woolf (2007) p. 262; Broun (2004c) pp. 133–134; Duncan (2002) p. 40.

- ^ Duncan (2002) pp. 40–41.

- ^ Gazzoli (2010) p. 71; Broun (2004b); Duncan (2002) p. 40.

- ^ McGuigan (2015a) p. 138; Duncan (2002) p. 40; Anderson (1908) p. 85 n. 4; Giles (1847) p. 214 bk. 2 ch. 13; Hardy (1840) p. 330 bk. 2 ch. 196.

- ^ Woolf (2007) p. 262; Anderson (1908) p. 84; Pertz (1866) p. 508.

- ^ The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 1058.6; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1058.6; Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 489 (n.d.).

- ^ Taylor, A (2016) p. 10; Clarkson (2014) ch. 9; Edmonds (2014) p. 209; Clarkson (2013); Davies (2009) p. 78; Edmonds (2009) p. 53; Woolf (2007) p. 262; Taylor, S (2006) p. 26; Broun (2004c) pp. 133–135; Clancy (2006); Duncan (2002) p. 41.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 9; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 9; Clarkson (2013); Broun (2004c) pp. 133–135; Duncan (2002) p. 41.

- ^ a b Clarkson (2013).

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 9; Edmonds (2014) p. 209; Clarkson (2013); Duncan (2002) p. 41.

- ^ Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 49.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 9 ¶¶ 11–14; Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 571; Clarkson (2013); Woolf (2007) p. 262; Taylor, S (2006) p. 26.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) p. 58.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 9 ¶ 13; Clarkson (2013); Parsons (2011) p. 123; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 49; Woolf (2007) p. 262.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 9 ¶ 13; Clarkson (2013); Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 49; Woolf (2007) p. 262.

- ^ O'Keeffe (2001) p. 115; Cotton MS Tiberius B I (n.d.).

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) pp. 58.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) p. 58–59.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) pp. 59–60.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) p. 59; Anderson (1922) p. 478; Stevenson (1856) p. 100; Stevenson (1835) p. 34.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) pp. 59–60; Broun (2007) p. 126; Forbes (1874) pp. 54–55 ch. 11, 181–183 ch. 11.

- ^ Lewis (1987) pp. 221, 221 fig. 138, 446; Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 026 (n.d.).

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) p. 52.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) p. 60, 73.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) p. 60; Anderson (1908) p. 92; Arnold (1885) p. 191 ch. 156; Stevenson (1855) p. 553.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) pp. 60, 75, 75 n. 19, 249, 249 n. 2; Anderson (1922) p. 593; Stevenson (1856) p. 112; Stevenson (1835) p. 51.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) pp. 60–61, 67–68, 73, 234.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) pp. 61–65, 67–68, 234.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) pp. 61–65; Scott (2004); Duncan (1996) pp. 228–231.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) pp. 65–68, 73, 234.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) pp. 73–78, 115, 234; Broun; Harrison (2007) pp. 148–149, 201, 217.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) pp. 75–76, 75 n. 21, 251; Broun; Harrison (2007) pp. 148–149, 201, 217; Anderson (1922) p. 579 n. 4, 600; Stevenson (1856) p. 110; Stevenson (1835) p. 47.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) pp. 75–76, 76 n. 22, 252; Broun; Harrison (2007) pp. 148–149, 201, 217; Anderson (1922) p. 603 n. 4; Stevenson (1835) p. 51.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) p. 76, 76 n. 23; Broun; Harrison (2007) pp. 148–149, 201, 217; Anderson (1922) p. 602 n. 5; Stevenson (1835) p. 51.

- ^ Toledo Candelaria (2018) pp. 73–78, 115, 234.

- ^ The Annals of Tigernach (2010) § 1093.4; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 1093.4; Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 488 (n.d.).

- ^ McGuigan (2015a) pp. 124–125, 193–195; Edmonds (2014) pp. 209–210; Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 575; Edmonds (2009) pp. 53–54; Woolf (2007) pp. 262–263; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 204–206.

- ^ McGuigan (2015a) p. 193; Clarkson (2014) ch. 9, 9 n. 22; Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 577; Clarkson (2013); Clarkson (2010) ch. 9; Edmonds (2009) p. 53; Woolf (2007) pp. 262–263, 263 n. 63; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 205; Broun (2004c) p. 138; Hicks (2003) p. 46; Durkan (1999) pp. 89–90; Driscoll (1998) p. 106; Shead (1969) p. 220; Raine (1886) p. 127; Haddan; Stubbs (1873) p. 11.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 9; Woolf (2007) p. 263.

- ^ Driscoll (2015) p. 12; Clarkson (2014) ch. 9; Davies (2009) pp. 76–77; Edmonds (2009) p. 53; Woolf (2007) p. 263.

- ^ a b Woolf (2007) p. 263.

- ^ McGuigan (2015a) pp. 124–125; Clarkson (2014) ch. 9; Davies (2009) p. 78; Edmonds (2009) p. 53.

- ^ Broun (2004c) p. 138 n. 115.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 9; Woolf (2007) p. 263 n. 65; Driscoll (1998) p. 106.

- ^ McGuigan (2015a) pp. 124–125; Clarkson (2014) ch. 9; Edmonds (2014) p. 210; Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 575–577; Parsons (2011) p. 131; Gazzoli (2010) pp. 70–71; Davies (2009) pp. 78–79; Edmonds (2009) pp. 53–54; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 204–205; Hicks (2003) pp. 46–47.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 9 ¶ 21–28; Edmonds (2014) p. 210; Edmonds (2009) pp. 53–54; Breeze (1992); Rose (1982) p. 122.

- ^ Edmonds (2014) p. 210; Charles-Edwards (2013) p. 575; Parsons (2011) p. 123; Edmonds (2009) pp. 49 n. 42, 54–55, 58.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) chs. 1 ¶ 29, 9 ¶¶ 19–28, 10 ¶ 6, 11 ¶ 5.

- ^ Breeze (1992).

- ^ Edmonds (2009) p. 54; Breeze (1992).

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 9 ¶ 28; Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 575–578; Parsons (2011) p. 133; Breeze (1992); Insley (1987) p. 183.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) chs. 9 ¶ 28, 10 ¶ 6; Edmonds (2014) p. 210; Edmonds (2009) pp. 53–54; Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 575–577; Gazzoli (2010) pp. 70–71.

- ^ Barlow (1992) p. 55, 55 n. 136; Harley MS 526 (n.d.).

- ^ Taylor, A (2016) p. 10; Clarkson (2014) chs. 9, 10; Woolf (2007) pp. 270–271; Anderson (1908) pp. 91–92; Arnold (1885) pp. 190–191 chs. 155–156; Stevenson (1855) pp. 552–553.

- ^ a b Woolf (2007) pp. 270–271.

- ^ Broun (2004c) p. 138.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 9; Broun (2004c) p. 138; Stubbs (1868) pp. 121–122.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 9; Clarkson (2012) ch. 11.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) chs. 9, 10; Clarkson (2013); Duncan (2002) p. 41.

- ^ Clarkson (2013); Broun (2004c) p. 138.

- ^ Edmonds (2014) p. 209.

- ^ Oram, RD (2011) p. 57; Oram, R (2004) p. 63.

References

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Anderson, AO, ed. (1908). Scottish Annals from English Chroniclers, A.D. 500 to 1286. London: David Nutt. OL 7115802M.

- Anderson, AO, ed. (1922). Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to 1286. Vol. 1. London: Oliver and Boyd. OL 14712679M.

- "Annals of Tigernach". Corpus of Electronic Texts (13 April 2005 ed.). University College Cork. 2005. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Arnold, T, ed. (1879). Henrici Archidiaconi Huntendunensis Historia Anglorum. The History of the English. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. London: Longman & Co. OL 16622993M.

- Arnold, T, ed. (1885). Symeonis Monachi Opera Omnia. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. Vol. 2. London: Longmans & Co.

- Barlow, F, ed. (1992) [1962]. The Life of King Edward Who Rests at Westminster. Oxford Medieval Texts (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-820203-2.

- "Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 488". Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. Oxford Digital Library. n.d. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 489". Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. Oxford Digital Library. n.d. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 026: Matthew Paris OSB, Chronica Maiora I". Parker Library on the Web. n.d. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "Corpus Christi College MS. 157". Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. Oxford Digital Library. n.d. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "Cotton MS Faustina B IX". British Library. n.d. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "Cotton MS Tiberius B I". British Library. n.d. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Forbes, AP, ed. (1874). Lives of S. Ninian and S. Kentigern. The Historians of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. OL 21853273M.

- Forester, T, ed. (1853). The Chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon: Comprising the History of England, From the Invasion of Julius Cæsar to the Accession of Henry II. Also, the Acts of Stephen, King of England and Duke of Normandy. Bohn's Antiquarian Library. London: Henry G. Bohn. OL 24434761M.

- Forester, T, ed. (1854). The Chronicle of Florence of Worcester, with the Two Continuations: Comprising Annals of English History, From the Departure of the Romans to the Reign of Edward I. Bohn's Antiquarian Library. London: Henry G. Bohn. OL 24871176M.

- Giles, JA, ed. (1847). William of Malmesbury's Chronicle of the Kings of England, From the Earliest Period to the Reign of King Stephen. Bohn's Antiquarian Library. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Haddan, AW; Stubbs, W, eds. (1873). Councils and Ecclesiastical Documents Relating to Great Britain and Ireland. Vol. 2, pt. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hardy, TD, ed. (1840). Willelmi Malmesbiriensis Monachi Gesta Regum Anglorum Atque Historia Novella. Vol. 1. London: English Historical Society. OL 24871887M.

- "Harley MS 526". British Library. n.d. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Michel, F, ed. (1836). Chroniques Anglo-Normandes. Vol. 2. Rouen: Édouard Frère.

- O'Keeffe, KO, ed. (2001). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Collaborative Edition. Vol. 5. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-491-7.

- Pertz, GH, ed. (1866). "Annales Aevi Suevici". Monumenta Germaniae Historica Scriptorum Tomus ... Inde Ab Anno Christi Qvingentesimo Vsqve Ad Annum Millesimvm et Qvingentesimvm. Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scriptores in Folio. Hanover: Hahn. ISSN 0343-2157.

- Raine, J, ed. (1886). The Historians of the Church of York and its Archbishops. Vol. 2. London: Longman & Co. OL 179068M.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1835). Chronica de Mailros. Edinburgh: The Bannatyne Club. OL 13999983M.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1853). The Church Historians of England. Vol. 2, pt. 1. London: Seeleys.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1855). The Church Historians of England. Vol. 3, pt. 2. London: Seeleys. OL 7055940M.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1856). The Church Historians of England. Vol. 4, pt. 1. London: Seeleys.

- Stubbs, W, ed. (1868). Chronica Magistri Rogeri de Houedene. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. Vol. 1. Longmans, Green, and Co. OL 16619297M.

- Swanton, M, ed. (1998) [1996]. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92129-5.

- "The Annals of Tigernach". Corpus of Electronic Texts (2 November 2010 ed.). University College Cork. 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (29 August 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (15 August 2012 ed.). University College Cork. 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- Thorpe, B, ed. (1848). Florentii Wigorniensis Monachi Chronicon ex Chronicis. Vol. 1. London: English Historical Society. OL 24871544M.

- Thorpe, B, ed. (1861). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. Vol. 1. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts.

Secondary sources

[edit]- Breeze, A (1992). "Old English Wassenas 'Retainers' in Gospatrick's Writ". Notes and Queries. 39 (3): 272–275. doi:10.1093/nq/39.3.272. eISSN 1471-6941. ISSN 0029-3970.

- Broun, D (2004a). "Duncan I (d. 1040)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8209. Retrieved 28 July 2016. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Broun, D (2004b). "Macbeth (d. 1057)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17356. Retrieved 9 February 2016. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Broun, D (2004c). "The Welsh Identity of the Kingdom of Strathclyde c.900–c.1200". The Innes Review. 55 (2): 111–180. doi:10.3366/inr.2004.55.2.111. eISSN 1745-5219. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Broun, D (2007). Scottish Independence and the Idea of Britain: From the Picts to Alexander III. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2360-0.

- Broun, D; Harrison, J, eds. (2007). The Chronicle of Melrose Abbey: A Stratigraphic Edition. Scottish History Society. Vol. 1. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-90624-529-3.

- Charles-Edwards, TM (2013). Wales and the Britons, 350–1064. The History of Wales. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Clancy, TO (2006). "Ystrad Clud". In Koch, JT (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 1818–1821. ISBN 1-85109-445-8.

- Clarkson, T (2010). The Men of the North: The Britons and Southern Scotland (EPUB). Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-1-907909-02-3.

- Clarkson, T (2012) [2011]. The Makers of Scotland: Picts, Romans, Gaels and Vikings (EPUB). Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited. ISBN 978-1-907909-01-6.

- Clarkson, T (2013). "The Last King of Strathclyde". History Scotland. 13 (6): 24–27. ISSN 1475-5270.

- Clarkson, T (2014). Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age (EPUB). Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-1-907909-25-2.

- Davies, JR (2009). "Bishop Kentigern Among the Britons". In Boardman, S; Davies, JR; Williamson, E (eds.). Saints' Cults in the Celtic World. Studies in Celtic History. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 66–90. ISBN 978-1-84383-432-8. ISSN 0261-9865.

- Douglas, D; Greenway, G, eds. (2007) [1953]. English Historical Documents, c. 1042–1189 (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-43951-7.

- Driscoll, ST (1998). "Church Archaeology in Glasgow and the Kingdom of Strathclyde". The Innes Review. 49 (2): 95–114. doi:10.3366/inr.1998.49.2.95. eISSN 1745-5219. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Driscoll, ST (2015). "In search of the Northern Britons in the Early Historic Era (AD 400–1100)". Essays on the Local History and Archaeology of West Central Scotland. Resource Assessment of Local History and Archaeology in West Central Scotland. Glasgow: Glasgow Museums. pp. 1–15.

- Duncan, AAM (1976). "The Battle of Carham, 1018". Scottish Historical Review. 55 (1): 20–28. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25529144.

- Duncan, AAM (1996) [1975]. Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom. The Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Mercat Press. ISBN 0-901824-83-6.

- Duncan, AAM (2002). The Kingship of the Scots, 842–1292: Succession and Independence. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1626-8.

- Durkan, J (1999). "Glasgow Diocese and the Claims of York". The Innes Review. 50 (2): 89–101. doi:10.3366/inr.1999.50.2.89. eISSN 1745-5219. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Edmonds, F (2009). "Personal Names and the Cult of Patrick in Eleventh-Century Strathclyde and Northumbria". In Boardman, S; Davies, JR; Williamson, E (eds.). Saints' Cults in the Celtic World. Studies in Celtic History. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 42–65. ISBN 978-1-84383-432-8. ISSN 0261-9865.

- Edmonds, F (2014). "The Emergence and Transformation of Medieval Cumbria". Scottish Historical Review. 93 (2): 195–216. doi:10.3366/shr.2014.0216. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241.

- Forte, A; Oram, RD; Pedersen, F (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- Gazzoli, P (2010). Anglo-Danish Relations in the Later Eleventh Century (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge.

- Hicks, DA (2003). Language, History and Onomastics in Medieval Cumbria: An Analysis of the Generative Usage of the Cumbric Habitative Generics Cair and Tref (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/7401.

- Insley, J (1987). "Some Aspects of Regional Variation in Early Middle English Personal Nomenclature". Leeds Studies in English. 18: 183–199. ISSN 0075-8566.

- Lewis, S (1987), The Art of Matthew Paris in Chronica Majora, California Studies in the History of Art, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-04981-0, OL 3163004M

- McGuigan, N (2015a). Neither Scotland nor England: Middle Britain, c.850–1150 (PhD thesis). University of St Andrews. hdl:10023/7829.

- McGuigan, N (2015b). "Review of A Ross, The Kings of Alba, c.1000–c.1130". Northern Scotland. 6 (1): 98–101. doi:10.3366/nor.2015.0090. eISSN 2042-2717. ISSN 0306-5278.

- Oram, R (2004). David I: The King who Made Scotland. Tempus Scottish Monarchs. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-2825-X.

- Oram, RD (2011). Domination and Lordship: Scotland 1070–1230. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1496-7.

- Parker, E (2014). "Siward the Dragon-Slayer: Mythmaking in Anglo-Scandinavian England". Neophilologus. 98 (3): 481–493. doi:10.1007/s11061-013-9371-3. eISSN 1572-8668. ISSN 0028-2677. S2CID 162326472.

- Parker, EC (2012). Anglo-Scandinavian Literature and the Post-Conquest Period (PhD thesis). University of Oxford.

- Parsons, DN (2011). "On the Origin of 'Hiberno-Norse Inversion-Compounds'" (PDF). The Journal of Scottish Name Studies. 5: 115–152. ISSN 2054-9385.

- Rose, RK (1982). "Cumbrian Society and the Anglo-Norman Church". Studies in Church History. 18: 119–135. doi:10.1017/S0424208400016089. eISSN 2059-0644. ISSN 0424-2084.

- Scott, WW (2004). "William I [William the Lion] (c.1142–1214)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29452. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Shead, NF (1969). "The Origins of the Medieval Diocese of Glasgow". Scottish Historical Review. 48 (2): 220–225. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25528830.

- Taylor, A (2016). The Shape of the State in Medieval Scotland, 1124–1290. Oxford Studies in Medieval European History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-874920-2.

- Taylor, S (2006). "The Early History and Languages of West Dunbartonshire". In Brown, I (ed.). Changing Identities, Ancient Roots: The History of West Dunbartonshire From Earliest Times. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 12–41. ISBN 978-0-7486-2561-1.

- Toledo Candelaria, M (2018). From Reformed Barbarian to 'Saint-King': Literary Portrayals of King Malcolm III Canmore (r. 1058–93) in Scottish Historical Narratives, c. 1100–1449 (PhD thesis). University of Guelph. hdl:10214/12957.

- Woolf, A (2010). "Reporting Scotland in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle". In Jorgensen, A (ed.). Reading the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: Language, Literature, History. Studies in the Early Middle Ages. Vol. 23. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. pp. 221–239. doi:10.1484/M.SEM-EB.3.4457. ISBN 978-2-503-52394-1.

- Woolf, A (2007). From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1233-8.