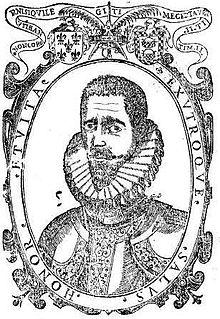

Luis Pacheco de Narváez

Luis Pacheco de Narváez | |

|---|---|

Luis Pacheco de Narváez | |

| Born | 1570 |

| Died | 1640 |

| Occupation | Writer, fencing master |

| Notable works | Libro de las grandezas de la espada |

Don Luis Pacheco de Narváez (1570–1640) was a Spanish writer on destreza, the Spanish art of fencing.[1]

He was a follower of Don Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza. Some of his earlier works were compendia of Carranza's work while his later works were less derivative. He served as fencing master to King Philip IV of Spain.

Nevertheless, it is not known exactly when Pacheco met his teacher, the greatest master of Spanish fencing, Jerónimo Sanchez de Carranza.[2][3]

Biography

[edit]Until recently, there has been no information on the exact date of birth of Pacheco de Narváez. Born in the city of Baeza, his life was devoted to working with weapons and becoming a sergeant major in the Canary Islands, namely on the island of Fuerteventura and Lanzarote.[4][5]

According to documents[6][7] from the legacy of Pacheco de Narváez in the Canary Islands, it is known that he was the son of Rodrigo Marin de Narváez and Magdalena Pacheco Cameras. He married Beatriz Fernandez de Cordoba, the daughter of Michael Jerome Fernandez de Cordova, clerk of the chamber and secretary of the Royal court of the Canary Islands and Lucia Sayago.[8][9]

In 1608, he fought a fencing match with Francisco de Quevedo as a result of Quevedo criticizing one of his works. Quevedo took off Pacheco's hat in the first encounter.[10][11]

In Quevedo's picaresque novel El Buscón,[12][13] this duel was parodied with a fencer relying on mathematical calculations having to run away from a duel with an experienced soldier.[14][15][16]

The life of a swordsman

[edit]Despite the lack of accurate data on the life of Pacheco de Narváez, as well as numerous other masters of medieval fencing, there are often occasional references, from which it is clear that the profession of the fencing master in Spain in the 15th and 16th centuries required serious preparation, extreme physical strength, and organization; thus, there existed a monopoly on teaching and awarding the title of master of the art of fencing.[17][18]

I was born with an innate fighting bias, just put my feet on the threshold of life and new forces, hit my ears in the ears and a special surprise was caused by the book Carranza.

Don Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza, a master of fencing and founder of the Spanish school of fencing, destreza, became famous for his written treatise La filosofía de las armas y de su destreza, y de la agresión y defensa cristiana ('The philosophy of arms and their skill, and of Christian aggression and defense', published in 1582) and became a mentor and fencing teacher for Pacheco de Narváez.[20][21]

Pacheco de Narváez was a military man who served on both land and sea as a soldier, sergeant, ensign, sergeant major, and later governor.[22][23]

Libro de las grandezas de la espada

[edit]

Libro de las grandezas de la espada ('Book of the Greatness of the sword') by Pacheco de Narváez formed the basis of all 17th-century Spanish fencing literature. The first edition includes all the principles that Narváez handed to Carranza. This book describes a number of secrets, principles and prescriptions, with the help of which anyone can learn and teach others without resorting to the instructions of other masters.

Libro de las grandezas de la espada was written in the city of Seville and is dedicated to Philip III, the "king of all Spain and the greater part of the world". As a pupil of Carranza, Pacheco de Narváez reproduces in detail the inventor's characteristic methods and explains the curious schemes, with drawn circles and positions of the blades relative to each other – in the form of conditional swords,[clarification needed] intersecting at different angles depending on the type of movement, the cutting or piercing stroke.

After extensive and detailed arguments on the need for defense, as required by human and divine laws, as well as arguments on the elevation of self-perfection through the art of possession of arms, the author consecrates his wisdom and practice in the art of fencing.[24][25]

In the middle of the 16th century, the stance according to the school of Spanish fencing was a popular stance in which the trunk is straightened, but so that the heart is not directly opposite the opponent's sword; right arm is straight, legs are not widely spaced. These foundations give three advantages: the point of the sword is directed as close as possible to the enemy, the swordsman holds the sword with more force, and thus eliminates the risk of injuring the elbow. It is not a question of crossing the swords with the enemy.

Fencers need to take a stand outside the distance in order to systematize the general concept of the right distance, Carranza and his follower Narváez represent[clarification needed] a circle drawn on the ground – "circonferencia imaginata entre los cuerpos contrarios" an 'imaginary circumference around the opposing bodies', which further outlines the actions.[26][27]

Carranza paid the most attention to cutting strokes, although he was very free to use stabbing blows in the fight. He presents the exact definition of the first strike, but does not explain the second one in any way. Narváez, however, touched on his work in thrusting strikes, but did not give any detailed explanation as to how he performed it.[28][29]

Modo fácil y nuevo para examinarse los maestros en la destreza de las armas

[edit]Modo fácil y nuevo para examinarse los maestros en la destreza de las armas ('A simple way of examining teachers in the art of fencing with weapons') is another of Pacheco de Narváez's most famous works (a dialogue between a pupil and an exam teacher on the philosophy and art of fencing).[30][31]

The seal of this work and any publishing house by other persons were prohibited without the appropriate permission. The book at that time was published by the Cabinet of Lazaro de los Ríos, Secretary of the King of Spain, dated 26 February 1625 in Madrid.[32][33]

This treatise contains a dialogue between the student and his teacher-examiner on the art of fencing and philosophy for obtaining the degree of maestro. In this form of writing, Pacheco de Narváez presented one hundred conclusions or forms of cognition.[34][35]

Pacheco de Narváez received gratitude from the king and was appointed examiner for all fencing teachers; however, instead of passing the exams, apparently, his comrades decided to unite against him. This can be concluded by analyzing the index la Matrícula de Yarza – a list of people who have been enrolled. The index is in the archives of the Supreme Court. It says the following:

Teachers of martial arts are suing Don Luis Pacheco de Narvaez, who must take the exam from all teachers.

— Luis Pacheco de Narváez, Letter L, file 4, 732

The protective pillars described in the treatise meet the requirements, correspond to the laws of justice and peace in the Republic. Each valiant knight was given a crown as a sign of wisdom and skill. Dialogue is based on these two principles. In the text, training with weapons is described. Also in this part, a thorough assessment of the most talented students is conducted. It is said that they are allocated a scholarship for the time devoted to studies. Such a person should be greeted favorably – the other, who from greed desires to receive the honor of receiving a scientific award – should not be despised or avoided working with. The involuntary ignoring of a person is not a significant mistake, but ignorance of what is necessary is disrespect to oneself. And above all, absurd[clarification needed] talent and a lack of courage lead to a loss of hope to achieve what is possible, says Pacheco de Narváez.[36]

This treatise is useful in studying the history of the art of possession of weapons, so intellectuals consider it valuable. This book contributed to the re-creation of the art and describes the image of the art of fencing from the date of publication of this was addressed only thanks to various masters of fencing.

Bibliography

[edit]- Libro de las grandezas de la espada, en qve se declaran mvchos secretos del que compuso el Commendador Geronimo de Carrança, Luis Pacheco de Narváez. Orbigo, 1600

- Compendio de la filosofia de las armas de Geronimo de Carrança, Luis Pacheco de Narváez por Luis Sanchez, 1612

- Сolloqvia familiaria et alia quae dam opuscula [de Erasmi de Civilitate morum puerilium] erudiendae imentuti accommodatissima opera doctisimorum... Luis Pacheco de Narváez. Claudius Bornat, 1643

- Nveva ciencia; y filosofia de la destreza de las armas, sv teorica, y practica: A la Magestad de Felipe Quarto, rey, y señor nvestro de las Españas, y de la mayor parte del mundo, Luis Pacheco de Narváez, M. Sanchez, 1672

- Modo facil y nueuo para examinar los maestros en la destreza de las armas, y entender sus cien conclusiones, ò formas de saber, Luis Pacheco de Narváez por los herederos de Pedro Lanaja, 1658

- Advertencias para la enseñanza de la filosofia, y destreza de las armas, assi à pie, como à cavallo ... por D. Luis Pacheco de Narvaez ..., Luis Pacheco de Narváez, 1642

- Historia exemplar de las dos constantes mugeres españolas ... por Don Luis Pacheco de Naruaez ..., Luis Pacheco de Narváez, Luis Imprenta del Reino (Madrid) 1635

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation. Thomas A. Green, 2010 – c. 254

- ^ Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books: Transmission and Tradition of Martial Arts in Europe (14th–17th Centuries), 2016 г. — С. 3, 329, 352

- ^ Jaquet, Daniel (2016). Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books: Transmission and Tradition of Martial Arts in Europe, 14th–17th Centuries (History of Warfare). BRILL. p. 636. ISBN 9789004324725.

- ^ Biografıas.Gregorio Marañón, Espasa-Calpe, 1970 – C. 621

- ^ Marañón, Gregorio (1970). Obras completas: Biografías. Espasa-Calpe.

- ^ Todos los documentos canarios que presentamos o comentamos aquí sobre Luis Pacheco se han tomado de la encomiable publicación de Pérez Herrero (2014)

- ^ Fernández, Juan I. Laguna. "Luis Pacheco de Narváez: Unos comentarios a la vida y escritos del campeón de la corte literaria barroca de Felipe III y Felipe IV, y su supuesta relación con el Tribunal de la justa venganza contra Francisco de Quevedo" (PDF). PARNASEO. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Protocolos Notariales, nº 1074, pp. 302r-202v. Fecha: 17 de julio de 1621. No obstante lo dicho indica Cioranescu (1957, pp. 353—354) que Beatriz Fernández de Córdoba era «nieta paterna de Alonso Fernández de Córdoba, natural de Gibraleón, teniente de gobernador de la isla de La Palma en 1524, regidor de la misma Isla y vecino después de La Gomera, donde había casado con Isabel Núñez, hija de Pedro Almonte y de Juana Hernández»

- ^ AHPLP: Protocolos Notariales, nº 902, pp. 294v-298r. Fecha: 25 de junio de 1591

- ^ [Obras de don Francisco de Quevedo Villegas. Francisco de Quevedo M. Rivadeneyra, 1852 – C.69–72] "Destreza Translation & Research Project: Famous Duels". Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 12 July 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Florencio, Janer. Obras de Don Francisco de Quevedo Villegas (1852–1877) – Quevedo, Francisco de, 1580–1645. Biblioteca de autores españoles, desde la formación del lenguaje hasta nuestros dias,23 ; 48 ; 69. Madrid : [s.n.], 1852–1877 (Imprenta y Esterotipia de M. Rivadeneyra). Retrieved 9 May 2018.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Quevedo: El Buscón.Francisco de Quevedo, Américo Castro, Julio Cejador y Frauca. Ediciones de «La Lectura», 1927 — С. 15,49

- ^ De Quevedo, Francisco (1927). "Quevedo: El Buscón". Books. Ediciones de "La Lectura". Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Quevedo, Francisco de (1670). "Buscon's departure from Alcala towards Segovia; His meeting with two Coxcombs, with whom he passed the time on the way; one was an Engineer, t'other a Fencer". The Life and Adventures of Buscon the Witty Spaniard. Put into English by a Person of Honour. To which is added, The Provident Knight. With a dedicatory letter signed: J. D. Henry Herringman. pp. 81–87.

- ^ Aparato biográfico y bibliográf.Francisco de Quevedo Rasco, 1897 – C. 565

- ^ De Quevedo, Francisco (1897). Obras completas de Don Francisco de Quevedo Villegas: Aparato biográfico y bibliográfico PDF Download. E. Rasco. p. 620.

- ^ Schools and masters of fencing. Noble art of blades, Egerton Castle

- ^ Castle, Egerton (2008). Schools and masters of fencing. Noble art of sword ownership. Center Poligraph. ISBN 978-5-9524-3799-9.

- ^ Nueva ciencia y filosofía de la destreza de las armas, su teórica y práctica, Madrid, 1672. – En el Prólogo al lector del Engaño y desengaño de los errores que se han querido introducir en la destreza de las armas (1635) se expresa Pacheco con igual ambigüedad sobre la época en que comenzó a dudar de las bondades del libro de Carranza: «paralelo corrió con lo más llegado a la primavera de mi edad; en los primeros crepúsculos de mi infancia, o, a lo menos, cuando le pagaba al tiempo las primicias de la juventud, se originó este constante sentimiento».

- ^ Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books: Transmission and Tradition of Martial Arts in Europe (14th–17th Centuries), 2016 г. — С. 3, 329, 352

- ^ Jaquet, Daniel (8 July 2016). Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books: Transmission and Tradition of Martial Arts in Europe, 14th–17th Centuries (History of Warfare). Brill Academic Pub. ISBN 978-9004312418.

- ^ Advertencias para la enseñanza de la filosofía y destreza de las armas así a pie como a caballo, 1642 (aprobación de 1639) – Prologo

- ^ de Narvaez., Luis Pacheco. "DESENGAÑO DE LA ESPADA Y NORTE DE DIESTROS". BIBLIOTEKADIGITAL. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ La novela barroca. Catálogo bio-bibliográfico (1620—1700), Begoña Ripoll, Universidad de Salamanca, 1991 – С.116

- ^ Pérez, Auladell (1991). "Begoña Ripoll, "La novela barroca. Catálogo Bio-Bibliográfico (1620–1700)"". Castilla: Estudios de Literatura (16). Ediciones Universidad de Valladolid: 231–234.

- ^ "La filosofía de las armas y de su destreza, y de la agresión y defensa cristiana. Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza, 1582

- ^ de Merich, Stefano. "La presencia del Libro de la filosofía de las armas de Carranza en el Quijote de 1615" (PDF). H-Net. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ Schools and masters of fencing. Noble art of sword ownership, Egerton Castle – P.137

- ^ Castle, Egerton. "Schools and masters of fencing. Noble art of sword ownership". PROFILIB. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ A simple way of examining teachers in the art of fencing with weapons. Don Luis Pacheco de Narvaez, [Translation from Spanish] —Dnepr: Serednjak T. К., 2017, — 112 с

- ^ "A simple way of examining teachers in the art of fencing with weapons. Luis Pacheco de Narvaez". Internet Archive. 28 August 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ Diálogo entre el maestro examinador en la Filosofía y Destreza de las Armas y el discípulo. Luis Pacheco de Narváez, 1625

- ^ Pacheco de Narváez, Luis. "Dialogo entre el Maestro examinador en la filosofía y destreça de las Armas y el Discipulo pidiendo el grado de Maestro en quien se declaran las cien conclusiones o formas de saber [Manuscrito]". Europeana. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ "Modo facil y nueuo para examinar los maestros en la destreza de las armas, y entender sus cien conclusiones, ò formas de saber" Luis Pacheco de Narváez por los herederos de Pedro Lanaja, 1658

- ^ Pacheco de Narváez, Luis (1658). "Modo facil y nueuo para examinar los maestros en la destreza de las armas, y entender sus cien conclusiones, ò formas de saber". Books. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ A simple way of examining teachers in the art of fencing with weapons. Don Luis Pacheco de Narvaez, [Translation from Spanish] —Dnepr: Serednjak T. К., 2017, — 112 с

Further reading

[edit]- Jaquet, Daniel; Verelst, Karin; Dawson, Timothy (2016). Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books: Transmission and Tradition of Martial Arts in Europe (14th–17th centuries). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004312418.

- Brea, Manuel Antonio (1805). Principios universales y reglas generales de la verdadera destreza (in Spanish). Madrid.

- de Tarsia, Pablo Antonio (1663). Vida de don Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas (in Spanish). Madrid.

- de Quevedo, Francisco (1980). La vida del buscón llamado Don Pablos (in Spanish).

- Tamariz, Nicolás (1696). Cartilla y luz en la verdadera destreza, sacada de los escritos de Don Luis Pacheco de Narváez y de los autores que refiere (in Spanish). Seville: Por los Herederos de Thomàs Lopez de Haro.

- Pacheco de Narváez, Luis (1702). Las tretas de la vulgar y comun esgrima de espada sola y con armas dobles, que reprobo Don Luis Pacheco de Narvaez, y las oposiciones que dispuso en verdadera destreza contra ellas (in Spanish). Zaragoza.

- Pacheco de Narváez, Luis; de Cala Gómez, Christoval (1898). Antiguos tratados de esgrima (siglo XVII) (in Spanish).

External links

[edit]- Facsimile of Libro de las grandezas de la Espada (in Spanish)

- Entry for the duel between Quevedo and Pacheco, Destreza Translation and Research Project

- Luis Pacheco de Narváez y Quevedo.(in Spanish)

- Paper on the life and works of Luis Pacheco de Narváez by Juan I. Laguna Fdez., «Luis Pacheco de Narváez: Unos comentarios a la vida y escritos del campeón de la corte literaria barroca de Felipe III y Felipe IV, y su supuesta relación con el “Tribunal de la justa venganza” contra Francisco de Quevedo», LEMIR, 20, 2016, pp. 191–324. (in Spanish)

- Libro de las grandezas de la espada Luis Pacheco de Narváez Biblioteca Digital Hispánica (in Spanish)

- Antiguos tratados de esgrima Luis Pacheco de Narvaez, Biblioteca Digital Hispánica (in Spanish)