African elephant

| African elephants | |

|---|---|

| |

| African bush elephant bull in Kruger National Park | |

| |

| African forest elephant in Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae |

| Tribe: | Loxodontini |

| Genus: | Loxodonta Anonymous, 1827[1] |

| Type species | |

| Elephas africana[1] Blumenbach, 1797

| |

| Species and Subspecies | |

| |

| |

range of living Loxodonta (2007)

| |

African elephants are members of the genus Loxodonta comprising two living elephant species, the African bush elephant (L. africana) and the smaller African forest elephant (L. cyclotis). Both are social herbivores with grey skin. However, they differ in the size and colour of their tusks as well as the shape and size of their ears and skulls.

Both species are at a pertinent risk of extinction according to the IUCN Red List; as of 2021, the bush elephant is considered endangered while the forest elephant is considered critically endangered. They are threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation, along with poaching for the illegal ivory trade in several range countries.

Loxodonta is one of two extant genera in the family Elephantidae. The name refers to the lozenge-shaped enamel of their molar teeth. Fossil remains of Loxodonta species have been found in Africa, spanning from the Late Miocene (from around 7–6 million years ago) onwards.

Etymology

[edit]The name Loxodonta comes from the Ancient Greek words λοξός (loxós, "slanting", "crosswise") and ὀδούς (odoús, "tooth"), referring to the lozenge-shaped enamel of the molar teeth, which differs significantly from the rounded shape of the Asian elephant's molar enamel.[2]

Taxonomy and evolution

[edit]

The first scientific description of the African elephant was written in 1797 by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, who proposed the scientific name Elephas africanus.[3] Loxodonte was proposed as a generic name for the African elephant by Frédéric Cuvier in 1825. An anonymous author used the Latinized spelling Loxodonta in 1827.[4] This author was recognized as authority by the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature in 1999.[1]

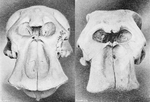

Elephas (Loxodonta) cyclotis was proposed by Paul Matschie in 1900, who described three African elephant zoological specimens from Cameroon whose skulls differed in shape from those of elephant skulls collected elsewhere in Africa.[5] In 1936, Glover Morrill Allen considered this elephant to be a distinct species and called it the 'forest elephant';[6] later authors considered it to be a subspecies.[7][8] Morphological and genetic analyses have since provided evidence for species-level differences between the African bush elephant and the African forest elephant.[9][10][11][12][13]

In 1907, Richard Lydekker proposed six African elephant subspecies based on the different sizes and shapes of their ears.[14] They are all considered synonymous with the African bush elephant.[1]

A third species, the West African elephant, has also been proposed but needs confirmation. It is thought that this lineage has been isolated from the others for 2.4 million years.[15]

Extinct African elephants

[edit]Between the late 18th and 21st centuries, the following extinct African elephants were described on the basis of fossil remains:

- North African elephant († Loxodonta africana pharaohensis) proposed by Paulus Edward Pieris Deraniyagala in 1948 was a specimen from Fayum in Egypt.[16]

- † Loxodonta atlantica was proposed as Elephas atlanticus by Auguste Pomel in 1879 based on a skull and bones found in Ternifine, Algeria.[17]

- † Loxodonta exoptata proposed by Wilhelm Otto Dietrich in 1941 was based on teeth found in Laetoli, Tanzania.[18]

- † Loxodonta adaurora proposed by Vincent Maglio in 1970 was a complete skeleton found in Kanapoi, Kenya.[19]

- † Loxodonta cookei proposed by William J. Sanders in 2007 based on teeth found in the Varswater Formation at Langebaanweg, South Africa.[20]

Phylogeny and evolution

[edit]Relationships of living and extinct elephants based on DNA, after Palkopoulou et al. 2018.[21]

| Elephantidae |

| ||||||||||||

The oldest species of Loxodonta known is Loxodonta cookei, with remains of the species known from around 7–5 million years ago, from remains found in Chad, Kenya, Uganda, and South Africa.[22]

Analysis of nuclear DNA sequences indicates that the genetic divergence between African bush and forest elephants dates 2.6 – 5.6 million years ago. The African forest elephant was found to have a high degree of genetic diversity, likely reflecting periodic fragmentation of their habitat during the changes in the Pleistocene.[12]

Gene flow between the two African elephant species was examined at 21 locations. The analysis revealed that several African bush elephants carried mitochondrial DNA of African forest elephants, indicating they hybridised in the savanna-forest transition zone in ancient times.[23] However, despite the hybridisation at the contact zone between the two species, there appears to have been little effective gene flow between the two species since their initial split.[21]

DNA from the European straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus) indicates that the extinct elephant genus Palaeoloxodon is more closely related to African elephants than to Asian elephants or mammoths. Analysis of the genome of P. antiquus also shows that Palaeloxodon extensively hybridised with African forest elephants, with the mitochondrial genome and over 30% of the nuclear genome of P. antiquus deriving from L. cyclotis. This ancestry is closer to modern west African populations than to central African populations of forest elephants.[21] Analysis of Chinese Palaeoloxodon mitogenomes suggests that this forest elephant ancestry was widely shared among Palaeoloxodon species.[24]

Description

[edit]Skin, ears, and trunk

[edit]

African elephants have grey folded skin up to 30 mm (1.2 in) thick that is covered with sparse, bristled dark-brown to black hair. Short tactile hair grows on the trunk, which has two finger-like processes at the tip, whereas Asian elephants only have one.[7] Their large ears help to reduce body heat. Flapping them creates air currents and exposes the ears' inner sides where large blood vessels increase heat loss during hot weather. The trunk is a prehensile elongation of its upper lip and nose. This highly sensitive organ is innervated primarily by the trigeminal nerve, and is thought to be manipulated by about 40,000–60,000 muscles. Because of this muscular structure, the trunk is so strong that elephants can use it to lift about 3% of their own body weight. They use it for smelling, touching, feeding, drinking, dusting, producing sounds, loading, defending and attacking.[25] Elephants sometimes swim underwater and use their trunks as snorkels.[26][27]

Tusks and molars

[edit]Both male and female African elephants have tusks that grow from deciduous teeth called tushes, which are replaced by tusks when calves are about one year old. Tusks are composed of dentin, which forms small diamond-shaped structures in the tusk's center that become larger at its periphery.[25] Tusks are primarily used to dig for roots and strip the bark from trees for food, for fighting each other during the mating season, and for defending themselves against predators. The tusks weigh from 23 to 45 kg (51–99 lb) and can be from 1.5 to 2.4 m (5–8 ft) long. They are curved forward and continue to grow throughout the elephant's lifetime.[28]

The dental formula of elephants is 1.0.3.30.0.3.3 × 2 = 26.[25] Elephants have four molars; each weighs about 5 kg (11 lb) and measures about 30 cm (12 in) long. As the front pair wears down and drops out in pieces, the back pair moves forward, and two new molars emerge in the back of the mouth. Elephants replace their teeth four to six times in their lifetimes. At around 40 to 60 years of age, the elephant loses the last of its molars and will likely die of starvation which is a common cause of death. African elephants have 24 teeth in total, six on each quadrant of the jaw. The enamel plates of the molars are fewer in number than in Asian elephants.[29] The enamel of the molar teeth wears into a distinctive lozenge/loxodont (<>) shape characteristic to all members of the genus Loxodonta.[22] While some extinct species of Loxodonta retained permanent premolar teeth, these have been lost in both living species.[30]

Size

[edit]

The African bush elephant is the largest terrestrial animal. Under optimal conditions where individuals are capable of reaching full growth potential, mature fully grown females are 2.47–2.73 m (8 ft 1 in – 8 ft 11 in) tall at the shoulder and weigh 2,600–3,500 kg (5,700–7,700 lb), while mature fully grown bulls are 3.04–3.36 m (10.0–11.0 ft) tall and weigh 5,200–6,900 kg (11,500–15,200 lb) on average. The largest recorded bull stood 3.96 metres (13.0 ft) at the shoulder, and is estimated to have weighed 10,400 kg (22,900 lb).[31] Its back is concave-shaped, while the back of the African forest elephant is nearly straight.[9] The African forest elephant is considerably smaller. Fully grown African forest elephant males in optimal conditions where individuals are capable of reaching full growth potential are estimated to be on average 2.09–2.31 metres (6.9–7.6 ft) tall and 1,700–2,300 kilograms (3,700–5,100 lb) in weight.[31]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]African elephants are distributed in Sub-Saharan Africa, where they inhabit Sahelian scrubland and arid regions, tropical rainforests, mopane and miombo woodlands. African forest elephant populations occur only in Central and West Africa.[32]

Behavior and ecology

[edit]Sleeping pattern

[edit]Elephants are the animals with the lowest sleep times, especially African elephants. Research has found their average sleep to be only 2 hours in 24-hour cycles.

Family

[edit]

Both African elephant species live in family units comprising several adult cows, their daughters and their subadult sons. Each family unit is led by an older cow known as the matriarch.[33][34] African forest elephant groups are less cohesive than African bush elephant groups, probably because of the lack of predators.[34]

When separate family units bond, they form kinship or bond groups. After puberty, male elephants tend to form close alliances with other males. While females are the most active members of African elephant groups, both male and female elephants are capable of distinguishing between hundreds of different low-frequency infrasonic calls to communicate with and identify each other.[35][36]

Elephants use some vocalisations that are beyond the hearing range of humans,[37] to communicate across large distances. Elephant mating rituals include the gentle entwining of trunks.[38]

Bulls were believed to be solitary animals, becoming independent once reaching maturity. New research suggests that bulls maintain ecological knowledge for the herd, facilitating survival when searching for food and water, which also benefits the young bulls who associate with them. Bulls only return to the herd to breed or to socialize; they do not provide prenatal care to their offspring, but rather play a fatherly role to younger bulls to show dominance.[39]

Feeding

[edit]While feeding, the African elephant uses its trunk to pluck leaves and its tusks to tear at branches, which can cause enormous damage to foliage.[28] Fermentation of the food takes place in the hindgut, enabling large food intakes.[40] The large size and hindgut of the African elephant also allows for the digestion of various plant parts, including fibrous stems, bark and roots.[41]

Intelligence

[edit]

African elephants are highly intelligent.[42] They have a very large and highly convoluted neocortex, a trait they share with humans, apes and some dolphin species. They are among the world's most intelligent species. With a mass of just over 5 kg (11 lb), the elephant brain is larger than that of any other terrestrial animal. The elephant's brain is similar to a human brain in terms of structure and complexity; the elephant's cortex has as many neurons as that of a human brain,[43] suggesting convergent evolution.[44]

Elephants exhibit a wide variety of behaviours, including those associated with grief, learning, mimicry, art, play, a sense of humor, altruism, use of tools, compassion, cooperation,[45] self-awareness, memory and possibly language.[46] All of these behaviors point to a highly intelligent species that is thought to be equal to cetaceans[47][48] and primates.[48]

The African elephant’s cognitive complexity includes behaviors indicative of empathy, problem-solving, and cooperative group behaviors. These traits underscore the evolutionary convergence of intelligence across species, similar to that seen in primates and cetaceans.[49]

Reproduction

[edit]African elephants are at their most fertile between the ages of 25 and 45. Calves are born after a gestation period of up to nearly two years.[50] The calves are cared for by their mother and other young females in the group, known as allomothering.[33]

African elephants show sexual dimorphism in weight and shoulder height by age 20, due to the rapid early growth of males. By age 25, males are double the weight of females; however, both sexes continue to grow throughout their lives.

Female African elephants are able to start reproducing at around 10 to 12 years of age,[51] and are in estrus for about 2 to 7 days. They do not mate at a specific time; however, they are less likely to reproduce in times of drought than when water is plentiful. The gestation period of an elephant is 22 months and fertile females usually give birth every 3–6 years, so if they live to around 50 years of age, they may produce 7 offspring. Females are a scarce and mobile resource for the males so there is intense competition to gain access to estrous females.

Post sexual maturity, males begin to experience musth, a physical and behavioral condition that is characterized by elevated testosterone, aggression and more sexual activity.[52][53] Musth also serves a purpose of calling attention to the females that they are of good quality, and it cannot be mimicked as certain calls or noises may be. Males sire few offspring in periods when they are not in musth. During the middle of estrus, female elephants look for males in musth to guard them. The females will yell, in a loud, low way to attract males from far away. Male elephants can also smell the hormones of a female ready for breeding. This leads males to compete with each other to mate, which results in the females mating with older, healthier males.[54] Females choose to a point who they mate with, since they are the ones who try to get males to compete to guard them. However, females are not guarded in the early and late stages of estrus, which may permit mating by younger males not in musth.[54]

Males over the age of 25 compete strongly for females in estrus, and are more successful the larger and more aggressive they are.[53] Bigger males tend to sire bigger offspring.[55] Wild males begin breeding in their thirties when they are at a size and weight that is competitive with other adult males. Male reproductive success is maximal in mid-adulthood and then begins to decline. However, this can depend on the ranking of the male within their group, as higher-ranking males maintain a higher rate of reproduction.[56] Most observed matings are by males in musth over 35 years of age. Twenty-two long observations showed that age and musth are extremely important factors; "… older males had markedly elevated paternity success compared with younger males, suggesting the possibility of sexual selection for longevity in this species."[52]: 287

Males usually stay with a female and her herd for about a month before moving on in search of another mate. Less than a third of the population of female elephants will be in estrus at any given time and the gestation period of an elephant is long, so it makes more evolutionary sense for a male to search for as many females as possible rather than stay with one group.[citation needed]

Threats

[edit]

Both species are threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation, and poaching for the illegal ivory trade is a threat in several range countries as well. The African bush elephant is listed as Endangered and the African forest elephant as Critically Endangered on the respective IUCN Red Lists.[57][58]

Based on vegetation types that provide suitable habitat for African elephants, it was estimated that in the early 19th century a maximum of 26,913,000 African elephants might have been present from the Sahel in the north to the Highveld in the south. Decrease of suitable habitat was the major cause for the decline of elephant populations until the 1950s. Hunting African elephants for the ivory trade accelerated the decline from the 1970s onwards. The carrying capacity of remaining suitable habitats was estimated at 8,985,000 elephants at most by 1987.[59] In the 1970s and 1980s, the price of ivory rose, and poaching for ivory increased, particularly in Central African range countries where access to elephant habitats was facilitated by logging and petroleum mining industries.[32] Between 1976 and 1980, about 830 t (820 long tons; 910 short tons) raw ivory was exported from Africa to Hong Kong and Japan, equivalent to tusks of about 222,000 African elephants.[60]

The first continental elephant census was carried out in 1976. At the time, 1.34 million elephants were estimated to range over 7,300,000 km2 (2,800,000 sq mi).[61] In the 1980s, it was difficult to carry out systematic surveys in several East African range countries due to civil wars.[32] In 1987, it was estimated that the African elephant population had declined to 760,000 individuals. In 1989, only 608,000 African elephants were estimated to have survived.[61] In 1989, the Kenyan Wildlife Service burned a stockpile of tusks in protest against the ivory trade.[62]

When the international ivory trade reopened in 2006, the demand and price for ivory increased in Asia. In Chad's Zakouma National Park, more than 3,200 elephants were killed between 2005 and 2010. The park did not have sufficient guards to combat poaching and their weapons were outdated. Well organized networks facilitated smuggling the ivory through Sudan.[63] The government of Tanzania estimated that more than 85,000 elephants were lost to poaching in Tanzania between 2009 and 2014, representing a 60% loss.[64] In 2012, a large upsurge in ivory poaching was reported, with about 70% of the product flowing to China.[65] China was the biggest market for poached ivory but announced that it would phase out the legal domestic manufacture and sale of ivory products in May 2015.[66]

Conflicts between elephants and a growing human population are a major issue in elephant conservation.[32] Human encroachment into natural areas where bush elephants occur or their increasing presence in adjacent areas has spurred research into methods of safely driving groups of elephants away from humans. Playback of the recorded sounds of angry Western honey bees has been found to be remarkably effective at prompting elephants to flee an area.[67] Farmers have tried scaring elephants away by more aggressive means such as fire or the use of chili peppers along fences to protect their crops.[68]

Conservation

[edit]In 1986, the African Elephant Database was initiated with the aim to monitor the status of African elephant populations. This database includes results from aerial surveys, dung counts, interviews with local people and data on poaching.[69]

In 1989, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora listed the African elephant on CITES Appendix I. This listing banned international trade of African elephants and their body parts by countries that signed the CITES agreement. Hunting elephants is banned in the Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Côte d'Ivoire, and Senegal. After the ban came into force in 1990, retail sales of ivory carvings in South Africa have plummeted by more than 95% within 10 years.[70] As a result of the trade ban, African elephant populations recovered in Southern African range countries.[71]

The African Elephant Specialist Group has set up a Human-Elephant Conflict Task Force with the aim to develop conflict mitigation strategies.[72]

In 2005, the West African Elephant Memorandum of Understanding was signed by 12 West African countries. The Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals provided financial support for four years to implement the West African Elephant Conservation Strategy, which forms the central component of this intergovernmental treaty.[73]

In 2019, the export of wild African elephants to zoos around the world was banned, with an exception added by the EU to allow export in "exceptional cases where … it is considered that a transfer to ex-situ locations will provide demonstrable in-situ conservation benefits for African elephants". Previously, export had been allowed in Southern Africa with Zimbabwe capturing and exporting more than 100 baby elephants to Chinese zoos since 2012.[74]

It was found that elephant conservation does not pose a trade-off with climate change mitigation. Although animals typically cause a reduction of woody biomass and therewith above-ground carbon, they foster soil carbon sequestration.[75]

In culture

[edit]Many African cultures revere the African elephant as a symbol of strength and power.[76][77] It is also praised for its size, longevity, stamina, mental faculties, cooperative spirit, and loyalty.[78] Its religious importance is mostly totemic.[79] Many societies believed that their chiefs would be reincarnated as elephants. In the 10th century, the people of Igbo-Ukwu in Nigeria buried their leaders with elephant tusks.[80]

South Africa uses elephant tusks in their coat of arms to represent wisdom, strength, moderation and eternity.[81]

In the western African Kingdom of Dahomey, the elephant was associated with the 19th century rulers of the Fon people, Guezo and his son Glele.[a] The animal is believed to evoke strength, royal legacy, and enduring memory as related by the proverbs: "There where the elephant passes in the forest, one knows" and "The animal steps on the ground, but the elephant steps down with strength."[82] Their flag depicted an elephant wearing a royal crown.

As national symbols

[edit]The coat of arms of the Central African Republic features the head of an elephant in the upper left quadrant of the shield. The version of the coat of arms of Guinea used from 1958 to 1984 featured a golden elephant in the centre of the shield. The coat of arms of Ivory Coast features the head of an elephant as the focal point of the emblem. The coat of arms of the Republic of the Congo has two elephants supporting the shield. The coat of arms of Eswatini has an elephant and a lion supporting the shield.

See also

[edit]- Africa's Elephant Kingdom

- Indian elephant

- List of individual elephants

- Sri Lankan elephant

- Sumatran elephant

Notes

[edit]- ^ Guezo and Glele ruled from 1818 to 1858 and from 1858 to 1889, respectively

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Shoshani, J. (2005). "Genus Loxodonta". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Cuvier, F. (1825). "Éléphants d'Afrique". In Geoffroy-Saint-Hilaire, É.; Cuvier, F. (eds.). Histoire Naturelle des Mammifères, avec des figures originales, coloriées, dessinées d'après des animaux vivans. Vol. Tome 6. Paris: A. Belain. pp. 117–118.

- ^ Blumenbach, J. F. (1797). "2. Africanus". Handbuch der Naturgeschichte [Handbook of Natural History] (Fifth ed.). Göttingen: Johann Christian Dieterich. p. 125.

- ^ Anonymous (1827). "Analytical Notices of Books. Histoire Naturelle des Mammifères, avec des Figures originale, dessinées d'après des Animaux vivans; &c. Par MM. Geoffroy-Saint-Hilaire, et F. Cuvier. Livraison 52 et 53". The Zoological Journal. 3 (9): 140–143.

- ^ Matschie, P. (1900). "Geographische Abarten des Afrikanischen Elefanten". Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin. 3: 189–197.

- ^ Allen, G. M. (1936). "Zoological results of the George Vanderbilt African Expedition of 1934. Part II — The forest elephant of Africa". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 88: 15–44. JSTOR 4064188.

- ^ a b Laurson, B.; Bekoff, M. (1978). "Loxodonta africana" (PDF). Mammalian Species (92): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3503889. JSTOR 3503889. S2CID 253949585. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ^ Estes, R. D. (1999). "Elephant Loxodonta africana Family Elephantidae, Order Proboscidea". The Safari Companion: A Guide to Watching African Mammals Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, and Primates (Revised and expanded ed.). Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing Company. pp. 223–233. ISBN 1-890132-44-6.

- ^ a b Grubb, P.; Groves, C. P.; Dudley, J. P. & Shoshani, J. (2000). "Living African elephants belong to two species: Loxodonta africana (Blumenbach, 1797) and Loxodonta cyclotis (Matschie, 1900)". Elephant. 2 (4): 1–4. doi:10.22237/elephant/1521732169.

- ^ Roca, A. L.; Georgiadis, N.; Pecon-Slattery, J. & O'Brien, S. J. (2001). "Genetic Evidence for Two Species of Elephant in Africa". Science. 293 (5534): 1473–1477. Bibcode:2001Sci...293.1473R. doi:10.1126/science.1059936. PMID 11520983. S2CID 38285623.

- ^ Rohland, N.; Malaspinas, A.-S.; Pollack, J. L.; Slatkin, M.; Matheus, P. & Hofreiter, M. (2007). "Proboscidean Mitogenomics: Chronology and Mode of Elephant Evolution Using Mastodon as Outgroup". PLOS Biology. 5 (8): e207. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050207. PMC 1925134. PMID 17676977.

- ^ a b Rohland, N.; Reich, D.; Mallick, S.; Meyer, M.; Green, R. E.; Georgiadis, N. J.; Roca, A. L. & Hofreiter, M. (2010). "Genomic DNA sequences from mastodon and woolly mammoth reveal deep speciation of forest and savanna elephants". PLOS Biology. 8 (12): e1000564. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000564. PMC 3006346. PMID 21203580.

- ^ Murphy, W. J.; Ishida, Y.; Oleksyk, T. K.; Georgiadis, N. J.; David, V. A.; Zhao, K.; Stephens, R. M.; Kolokotronis, S.-O. & Roca, A. L. (2011). "Reconciling Apparent Conflicts between Mitochondrial and Nuclear Phylogenies in African Elephants". PLOS ONE. 6 (6): e20642. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...620642I. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020642. PMC 3110795. PMID 21701575.

- ^ Lydekker, R. (1907). "The Ears as a Race-Character in the African Elephant". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (January to April): 380–403. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1907.tb01824.x.

- ^ Eggert, L.S.; Rasner, C.A. & Woodruff, D.S. (2002). "The evolution and phylogeography of the African elephant inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequence and nuclear microsatellite markers". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 269 (1504): 1993–2006. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2070. PMC 1691127. PMID 12396498.

- ^ Deraniyagala, P. E. P. (1955). Some extinct elephants, their relatives, and the two living species. Colombo: Ceylon National Museums Publication.

- ^ Pomel, A. (1897). "Elephas atlanticus Pom.". Les éléphants quaternaires. Paléontologie : monographies. Alger: P. Fontana & Co. pp. 42–59.

- ^ Dietrich, W. O. (1941). "Die säugetierpaläontologischen Ergebnisse der Kohl-Larsen'schen Expedition 1937–1939 im nördlichen Deutsch-Ostafrika". Zentralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie. B (8): 217–223.

- ^ Maglio, V. J. (1970). "Four new species of Elephantidae from the Plio-Pleistocene of northwestern Kenya". Breviora (341): 1–43.

- ^ Sanders, W. (2007). "Taxonomic review of fossil Proboscidea (Mammalia) from Langebaanweg, South Africa" (PDF). Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa. 62 (1) (Online ed.): 1–16. Bibcode:2007TRSSA..62....1S. doi:10.1080/00359190709519192. S2CID 27499106.

- ^ a b c Eleftheria Palkopoulou; Mark Lipson; Swapan Mallick; Svend Nielsen; Nadin Rohland; Sina Baleka; Emil Karpinski; Atma M. Ivancevic; Thu-Hien To; R. Daniel Kortschak; Joy M. Raison; Zhipeng Qu; Tat-Jun Chin; Kurt W. Alt; Stefan Claesson; Love Dalén; Ross D. E. MacPhee; Harald Meller; Alfred L. Roca; Oliver A. Ryder; David Heiman; Sarah Young; Matthew Breen; Christina Williams; Bronwen L. Aken; Magali Ruffier; Elinor Karlsson; Jeremy Johnson; Federica Di Palma; Jessica Alfoldi; David L. Adelson; Thomas Mailund; Kasper Munch; Kerstin Lindblad-Toh; Michael Hofreiter; Hendrik Poinar; David Reich (2018). "A comprehensive genomic history of extinct and living elephants". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (11): E2566 – E2574. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115E2566P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1720554115. PMC 5856550. PMID 29483247.

- ^ a b Sanders, William J. (7 July 2023). Evolution and Fossil Record of African Proboscidea (1 ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 154, 205–208. doi:10.1201/b20016. ISBN 978-1-315-11891-8.

- ^ Roca, A. L.; Georgiadis, N. & O'Brien, S. J. (2004). "Cytonuclear genomic dissociation in African elephant species" (PDF). Nature Genetics. 37 (1): 96–100. doi:10.1038/ng1485. PMID 15592471. S2CID 10029589. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Lin, Haifeng; Hu, Jiaming; Baleka, Sina; Yuan, Junxia; Chen, Xi; Xiao, Bo; Song, Shiwen; Du, Zhicheng; Lai, Xulong; Hofreiter, Michael; Sheng, Guilian (July 2023). "A genetic glimpse of the Chinese straight-tusked elephants". Biology Letters. 19 (7). doi:10.1098/rsbl.2023.0078. ISSN 1744-957X. PMC 10353889. PMID 37463654.

- ^ a b c Shoshani, J. (1978). "General information on elephants with emphasis on tusks". Elephant. 1 (2): 20–31. doi:10.22237/elephant/1491234053.

- ^ West, J.B. (April 2002). "Why doesn't the elephant have a pleural space?". News in Physiological Sciences. 17 (2): 47–50. doi:10.1152/nips.01374.2001. PMID 11909991. S2CID 27321751.

- ^ Sandybinns. "25 Things You Might Not Know About Elephants". International Elephant Foundation. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ a b Burnie, D. (2001). Animal. London: Dorling Kindersley.

- ^ Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1987). A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. Cambridge University Press. p. 208. ISBN 0-521-34697-5.

- ^ Sanders, William J. (17 February 2018). "Horizontal tooth displacement and premolar occurrence in elephants and other elephantiform proboscideans". Historical Biology. 30 (1–2): 137–156. Bibcode:2018HBio...30..137S. doi:10.1080/08912963.2017.1297436. ISSN 0891-2963.

- ^ a b Larramendi, A. (2016). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61 (3): 537–574. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014. S2CID 2092950.

- ^ a b c d Blanc, J. J.; Thouless, C. R.; Hart, J. A.; Dublin, H. T.; Douglas-Hamilton, I.; Craig, G. C.; Barnes, R. F. W. (2003). African Elephant Status Report 2002: An update from the African Elephant Database. Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 29. Gland and Cambridge: IUCN. ISBN 9782831707075.

- ^ a b Douglas-Hamilton, I. (1972). On the ecology and behaviour of the African elephant: the elephants of Lake Manyara (PhD thesis). Oxford: University of Oxford. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.453899.

- ^ a b Turkalo, A.; Barnes, R. (2013). "Loxodonta cyclotis Forest Elephant". In Kingdon, J.; Happold, D.; Hoffmann, M.; Butynski, T.; Happold, M.; Kalina, J. (eds.). The Mammals of Africa. Vol. I. Introductory Chapters and Afrotheria. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 195–200. ISBN 9781408189962.

- ^ McComb, K.; Moss, C.; Sayialel, S.; Baker, L. (2000). "Unusually extensive networks of vocal recognition in African elephants". Animal Behaviour. 59 (6): 1103–1109. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.332.7064. doi:10.1006/anbe.2000.1406. PMID 10877888. S2CID 17628123.

- ^ McComb, K.; Moss, C.; Durant, S. M.; Baker, L.; Sayialel, S. (2001). "Matriarchs As Repositories of Social Knowledge in African Elephants". Science. 292 (5516): 491–494. Bibcode:2001Sci...292..491M. doi:10.1126/science.1057895. PMID 11313492. S2CID 17594461.

- ^ Herbst, C. T.; Stoeger, A. S.; Frey, R.; Lohscheller, J.; Titze, I.; Gumpenberger, M.; Fitch, W. T. (2012). "How Low Can You Go? Physical Production Mechanism of Elephant Infrasonic Vocalizations". Science. 337 (6094): 595–599. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..595H. doi:10.1126/science.1219712. PMID 22859490. S2CID 32792564.

- ^ Buss, I.; Smith, N. (1966). Observations on Reproduction and Breeding Behavior of the African Elephant (PDF). Allen Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ^ Briggs, H. (2020). "Secrets of male elephant society revealed in the wild". BBC News. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ Clauss, M.; Frey, R.; Kiefer, B.; Lechner-Doll, M.; Loehlein, W.; Polster, C.; Roessner, G. E.; Streich, W. J. (2003). "The maximum attainable body size of herbivorous mammals: morphophysiological constraints on foregut, and adaptations of hindgut fermenters" (PDF). Oecologia. 136 (1): 14–27. Bibcode:2003Oecol.136...14C. doi:10.1007/s00442-003-1254-z. PMID 12712314. S2CID 206989975. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Owen-Smith, Norman; Chafota, Jonas (28 June 2012). "Selective feeding by a megaherbivore, the African elephant (Loxodonta africana)". Journal of Mammalogy. 93 (3): 698–705. doi:10.1644/11-MAMM-A-350.1. S2CID 83726553.

- ^ Plotnik, J. M.; De Waal, F. B.; Reiss, D. (2006). "Self-recognition in an Asian elephant". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (45): 17053–17057. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10317053P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608062103. PMC 1636577. PMID 17075063.

- ^ Roth, G.; Stamenov, M. I.; Gallese, V. (2003). "Is the human brain unique?". Mirror Neurons and the Evolution of Brain and Language. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 63–76. doi:10.1002/0470867221.ch2. ISBN 978-0-470-84960-6.

- ^ Goodman, M.; Sterner, K.; Islam, M.; Uddin, M.; Sherwood, C.; Hof, P.; Hou, Z.; Lipovich, L.; Jia, H.; Grossman, L.; Wildman, D. (2009). "Phylogenomic analyses reveal convergent patterns of adaptive evolution in elephant and human ancestries". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (49): 20824–20829. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10620824G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0911239106. PMC 2791620. PMID 19926857.

- ^ Plotnik, J. M.; Suphachoksahakun, W.; Lair, R.; Plotnik, J. M. (2011). "Elephants know when they need assistance in a cooperative task". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (12): 5116–5121. doi:10.1073/pnas.1101765108. PMC 3064331. PMID 21383191.

- ^ Parsell, D. L. (2003). "In Africa, Decoding the 'Language' of Elephants". National Geographic Magazine News. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2007.

- ^ Viegas, J. (2011). "Elephants smart as chimps, dolphins". ABC Science. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ a b Viegas, J. (2011). "Elephants Outwit Humans During Intelligence Test". Discovery News. Archived from the original on 8 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Plotnik, J. M.; Suphachoksahakun, W. (2011). "Elephants know when they need assistance in a cooperative task". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (12): 5116–5121. doi:10.1073/pnas.1101765108. PMC 3064331. PMID 21383191.

- ^ Macdonald, D. (2001). The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Benedict, F. G. (1936). "The physiology of the elephant". Carnegie Inst. Washington Pub. No. 474. 1.

- ^ a b Hollister-Smith, J. A.; Poole, J. H.; Archie, E. A.; Vance, E. A.; Georgiadis, N. J.; Moss, C. J.; Alberts, S. C. (2007). "Age, musth, and paternity success in wild male African elephants, Loxodonta africana" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 74 (2): 287–296. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.12.008. S2CID 54327948. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2015.

- ^ a b Sukumar, R. (2003). "Sexual selection and mate choice". The Living Elephants: Evolutionary Ecology, Behavior, and Conservation. Oxford, USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 112–124. ISBN 0-19-510778-0.

- ^ a b Poole, Joyce H. (1989). "Mate guarding, reproductive success and female choice in African elephants". Animal Behaviour. 37: 842–849. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(89)90068-7. S2CID 53150105.

- ^ Lee, Phyllis C.; Moss, Cynthia J. (1986). "Early maternal investment in male and female African elephant calves". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 18 (5): 353–361. Bibcode:1986BEcoS..18..353L. doi:10.1007/bf00299666. S2CID 10901693.

- ^ Loizi, H.; Goodwin, T. E.; Rasmussen, L. E. L.; Whitehouse, A. M.; Schulte, B. A. (2009). "Sexual dimorphism in the performance of chemosensory investigatory behaviours by African elephants (Loxodonta africana)". Behaviour. 146 (3): 373–392. doi:10.1163/156853909X410964.

- ^ Gobush, K.S.; Edwards, C.T.T.; Balfour, D.; Wittemyer, G.; Maisels, F.; Taylor, R.D. (2022) [amended version of 2021 assessment]. "Loxodonta africana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T181008073A223031019. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T181008073A223031019.en.

- ^ Gobush, K.S.; Edwards, C.T.T.; Maisels, F.; Wittemyer, G.; Balfour, D.; Taylor, R.D. (2021) [errata version of 2021 assessment]. "Loxodonta cyclotis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T181007989A204404464. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T181007989A204404464.en.

- ^ Milner-Gulland, E. J.; Beddington, J. R. (1993). "The exploitation of elephants for the ivory trade: an historical perspective". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 252 (1333): 29–37. Bibcode:1993RSPSB.252...29M. doi:10.1098/rspb.1993.0042. S2CID 128704128.

- ^ Parker, J. S. C.; Martin, E. B. (1982). "How many elephants are killed for the ivory trade?" (PDF). Oryx. 16 (3): 235–239. doi:10.1017/S0030605300017452.

- ^ a b Stiles, D. (2004). "The ivory trade and elephant conservation" (PDF). Environmental Conservation. 31 (4): 309–321. Bibcode:2004EnvCo..31..309S. doi:10.1017/S0376892904001614. S2CID 14772884.

- ^ Poole, J. (1996). Coming of Age With Elephants. New York: Hyperion. p. 232. ISBN 0-7868-6095-2.

- ^ Poilecot, P. (2010). "Le braconnage et la population d'éléphants au Parc National de Zakouma (Tchad)". Bois et Forêts des Tropiques. 303 (303): 93–102. doi:10.19182/bft2010.303.a20454.

- ^ Mathiesen, K. (2015). "Tanzania elephant population declined by 60% in five years, census reveals". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ Gettleman, J. (3 September 2012). "Elephants Dying in Epic Frenzy as Ivory Fuels Wars and Profits". The New York Times.

- ^ Fergus Ryan (26 September 2015). "China and US agree on ivory ban in bid to end illegal trade globally". The Guardian.

- ^ King, L. E.; Douglas-Hamilton, I.; Vollrath, F. (2007). "African elephants run from the sound of disturbed bees". Current Biology. 17 (19): R832 – R833. Bibcode:2007CBio...17.R832K. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.038. PMID 17925207. S2CID 30014793.

- ^ Snyder, K.; Mneney, P.; Benjamin, B.; Mkilindi, P.; Mbise, N. (2019). "Seasonal and spatial vulnerability to agricultural damage by elephants in the western Serengeti, Tanzania" (PDF). Oryx. 55 (1): 139–149. doi:10.1017/S0030605318001382.

- ^ Thouless, C. R.; Dublin, H. T.; Blanc, J. J.; Skinner, D. P.; Daniel, T. E.; Taylor, R. D.; Maisels, F.; Frederick, H. L.; Bouché, P. (2016). African Elephant Status Report 2016 : an update from the African Elephant Database (PDF). Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 60. Gland: IUCN SSC African Elephant Specialist Group. ISBN 978-2-8317-1813-2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Stiles, D.; Martin, E. (2001). "Status and trends of the ivory trade in Africa, 1989–1999" (PDF). Pachyderm (30): 24–36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ Blanc, J. J.; Barnes, R. F. W.; Craig, G. C.; Dublin, H. T.; Thouless, C. R.; Douglas-Hamilton, I.; Hart, J. A. (2007). African Elephant Status Report 2007: An update from the African Elephant Database (PDF). Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 33. Gland: IUCN SSC African Elephant Specialist Group.

- ^ Naughton, L.; Rose, R.; Treves, A. (1999). The social dimensions of human-elephant conflict in Africa: A literature review and case studies from Uganda and Cameroon. Madison: University of Wisconsin.

- ^ Dublin, H. (2005). "African Elephant Specialist Group report". Pachyderm (39): 1–9.

- ^ "Near-total ban imposed on sending wild African elephants to zoos".

- ^ Sandhage-Hofmann, A.; Linstädter, A.; Kindermann, L.; Angombe, S.; Amelung, W. (2021). "Conservation with elevated elephant densities sequesters carbon in soils despite losses of woody biomass". Global Change Biology. 27 (19): 4601–4614. doi:10.1111/gcb.15779. PMID 34197679.

- ^ "383. African Elephant (Loxodonta africana)". EDGE: Mammal Species Information. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ "West African Elephants". Convention on Migratory Species. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ "Elephant: The Animal and Its Ivory in African Culture". Fowler Museum at UCLA. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ^ Sukumar, R. (2003). "The capture and use of the African elephant". The Living Elephants: Evolutionary Ecology, Behaviour, and Conservation. Oxford, USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 81–88. ISBN 978-0-19-510778-4. OCLC 935260783.

- ^ Wylie, D. (2009). Elephant. Reaktion Books. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-86189-615-5. OCLC 740873839.

- ^ "National Coat of Arms". South African Government Information. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ "Elephant Figure | Fon peoples | The Met". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

External links

[edit]- "Loxodonta africana". Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. 2020.

- Elephant Information Repository Archived 18 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine – An in-depth resource on elephants

- "Elephant caves" of Mt Elgon National Park

- ElephantVoices – Resource on elephant vocal communications

- Amboseli Trust for Elephants – Interactive web site

- Another Elephant – A hub for saving the elephants.

- David Quammen (2008). "Family ties – The elephants of Samburu". National Geographic Magazine. Archived from the original on 26 August 2008.

- EIA 25 yrs investigating the ivory trade, reports etc

- EIA (in the USA) reports etc

- International Elephant Foundation

- [1]

- [2]

- African elephants

- Mammals of Sub-Saharan Africa

- EDGE species

- Animal species groups

- National symbols of the Central African Republic

- National symbols of Equatorial Guinea

- National symbols of Ghana

- National symbols of Guinea

- National symbols of Ivory Coast

- National symbols of the Republic of the Congo

- National symbols of São Tomé and Príncipe

- National symbols of Eswatini

- Extant Pliocene first appearances