Look Back in Anger (1959 film)

| Look Back in Anger | |

|---|---|

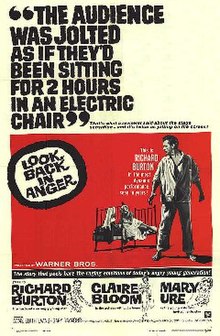

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Tony Richardson |

| Written by | Nigel Kneale |

| Based on | Look Back in Anger by John Osborne |

| Produced by | Harry Saltzman Gordon Scott |

| Starring | Richard Burton Claire Bloom Mary Ure Edith Evans |

| Cinematography | Oswald Morris |

| Edited by | Richard Best |

| Music by | Chris Barber |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £250,000[2] |

| Box office | $1.1 million (est. US/ Canada rentals)[3] |

Look Back in Anger is a 1959 British kitchen sink drama film starring Richard Burton, Claire Bloom and Mary Ure and directed by Tony Richardson. The film is based on John Osborne's play about a love triangle involving an intelligent but disaffected working-class young man (Jimmy Porter), his upper-middle-class, impassive wife (Alison) and her haughty best friend (Helena Charles). Cliff, an amiable Welsh lodger, attempts to keep the peace. The character of Ma Tanner, only referred to in the play, is brought to life in the film by Edith Evans as a dramatic device to emphasise the class difference between Jimmy and Alison. The film and play are classic examples of the British cultural movement known as kitchen sink realism.

Plot

[edit]Jimmy and Alison Porter, a young married couple, live in a Midlands industrial town (Derby) in a shabby attic flat, which they share with Jimmy's best friend and business partner, Cliff. Despite graduating from university, Jimmy and Cliff make a meagre living running a sweet-stall in the local market. Jimmy's inability to climb the socioeconomic ladder, coupled with other injustices he sees around him make him angry at society, particularly to those in authority. He takes out his frustrations on his wife Alison, a submissive girl from an upper-middle-class family. Jimmy's love for Alison is mixed with contempt, as he feels she never had to experience want, pain, or suffering. He verbally abuses her telling her, in temper, that he wishes she would have a child that would die. Unbeknownst to Jimmy, Alison is pregnant, and having mixed feelings about the pregnancy and her marriage.

Tensions heighten between the couple when Alison invites her assertive friend, Helena, whom Jimmy loathes, to temporarily stay with them. After witnessing Jimmy's treatment of Alison, Helena persuades Alison to leave Jimmy on the same day that Ma Tanner, who lent Jimmy the money to set up his stall, has a fatal stroke. Eventually, Alison moves out and departs with her kindly father, Colonel Redfern, who has come to collect her. A grieving Jimmy returns to the flat to find Alison gone, and learns for the first time that she is pregnant. He starts an emotional tirade with Helena, who first slaps him but then kisses him passionately, and the two begin an affair.

Months later, Jimmy and Helena have settled into a comfortable relationship, but Jimmy is still hurt at Alison's departure. She, living in her parents' tranquil home, is having a precarious pregnancy, and fears that Jimmy's wish for her to suffer tragedy might come true. Cliff decides to strike out on his own, and Jimmy and Helena see him off at the railway station. After Cliff's train departs, Jimmy and Helena see Alison sitting disconsolately in the station. Alison explains to Helena that she has lost the baby and Helena, realizing that she was wrong to break up their marriage, informs Jimmy that she is leaving him. Jimmy and Alison reconcile.

Cast

[edit]- Richard Burton as Jimmy Porter

- Claire Bloom as Helena Charles

- Mary Ure as Alison Porter

- Edith Evans as Ma Tanner

- Gary Raymond as Cliff Lewis

- Glen Byam Shaw as Colonel Redfern

- Phyllis Neilson-Terry as Mrs. Redfern

- Donald Pleasence as Hurst, the market inspector

- George Devine as Doctor

- Walter Hudd as Actor

- Nigel Davenport as 1st Commercial Traveller

- Alfred Lynch as 2nd Commercial Traveller

- Toke Townley as Spectacled Man

- S. P. Kapoor as himself

Production

[edit]Look Back in Anger was produced by the Canadian impresario Harry Saltzman, who was seen an obvious choice as he was a fan of the play and it was he who had urged Osborne and Richardson to set up Woodfall Film Productions. The film was to be Woodfall's first production.

Osborne insisted, against resistance from Saltzman, that Richardson was the right man to direct the film.[4] Richardson had directed the original theatrical production but had no track record in feature films. The original backer, J. Arthur Rank, pulled out of the deal because of the choice of director.

Casting

[edit]Saltzman and Richardson persuaded Richard Burton to take on the title role, at a much lower fee than his accustomed Hollywood payoff. (His fee for the film was $125,000.)[5] It is not known what Kenneth Haigh, who had created the role, thought of this. The idea of recruiting Nigel Kneale to extend the play into a screenplay is credited to the influential theatre critic Kenneth Tynan (who had been in large part responsible for the incredible success of the play). Osborne was relieved at not having to do the job and handed over story rights for a mere £2,000.[6]

The part of the doctor was specially created for George Devine, the artistic director of the English Stage Company and the man to whom Osborne most owed his success. Glen Byam Shaw, Devine's longtime collaborator (they created the Young Vic Company), was handed the role of Colonel Redfern. Two other members of the English Stage Company, Nigel Davenport and Alfred Lynch, were given small roles as commercial salesmen who try to pick up Alison and Helena in the railway station bar. The Chris Barber jazz band appears in the opening scenes set at a jazz club.

Filming locations

[edit]Interiors were shot at Elstree Studios in September 1958. Some establishing shots were shot in Derby but the market scenes were shot in Deptford market; the railway station was Dalston Junction. Deptford and Dalston are in fact in the London area. The first market scenes were shot in the centre of Romford Market, Romford, Essex (now in the east London Borough of Havering).[7]

The scenes showing the street outside Jimmy and Alison Porter's flat were filmed in Harvist Road, London N7. The road was later demolished by Islington Borough Council and rebuilt as the Harvist Estate.[7]

Release

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film was not successful at first. Westminster Council gave it an X certificate, and it opened on 29 May 1959 during one of London's rare heatwaves.[8] Tim Adler wrote that Richardson never found out whether the film made a profit.[9] Burton was widely felt to be too old and mature-looking for the young character he played.

According to Kinematograph Weekly the film performed "better than average" at the British box office in 1959.[10]

Awards

[edit]The film was nominated in four categories for the 1959 BAFTA Awards: Best British Actor (Richard Burton), Best British Film, Best British Screenplay (Nigel Kneale) and Best Film from any Source. However, it won none, the winners being respectively Peter Sellers (I'm All Right Jack), Sapphire, Frank Harvey, John Boulting and Alan Hackney for I'm All Right Jack and Ben-Hur.

Burton was also nominated as Best Motion Picture Actor – Drama for the 1959 Golden Globes, but the award went to Anthony Franciosa in Career.

DVD release

[edit]A DVD was released in 2001 with the film's original aspect ratio of 1.66:1. A Blu-ray 1080p version was released by the British Film Institute in 2018 which includes several special features.[11]

Sources

[edit]- Osborne, John (1991). Almost a Gentleman. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-16635-0.

- Adler, Tim (2012). The House of Redgrave. London: Aurum. ISBN 978-1-84513-623-9.

- Richardson, Tony (1993). Long Distance Runner – A memoir. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-16852-3.

References

[edit]- ^ "Overview". TCM. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Alexander Walker, Hollywood, England, Stein and Day, 1974 p59

- ^ "1959: Probable Domestic Take", Variety, 6 January 1960 p 34

- ^ He wrote "This was based not on blind loyalty but on my untutored faith in his flair and his being the only possible commander to lead Woodfall's opening assault on the suburban vapidity of British film-making". (Osborne, p. 107)

- ^ James Chapman (2014) The Trouble with Harry: The Difficult Relationship of Harry Saltzman and Film Finances, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 34:1, 43-71, p 52 DOI: 10.1080/01439685.2014.879001

- ^ Osborne, p. 108.

- ^ a b "Look Back in Anger". ReelStreets. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ Richardson 1993.

- ^ Adler, p.70

- ^ Billings, Josh (17 December 1959). "Other better-than-average offerings". Kinematograph Weekly. p. 7.

- ^ "Look Back in Anger Blu-ray". Blu-Ray.com. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

External links

[edit]- 1959 films

- 1959 directorial debut films

- 1959 drama films

- British black-and-white films

- British drama films

- British films based on plays

- 1950s English-language films

- Films about dysfunctional families

- Films about social class

- Films based on works by John Osborne

- Films directed by Tony Richardson

- Films produced by Harry Saltzman

- Films set in Derbyshire

- Films shot at Associated British Studios

- 1950s pregnancy films

- Films about social realism

- British pregnancy films

- 1950s British films

- English-language drama films