War on terror

| War on Terror | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the post-Cold War and post-9/11 eras | |||||||

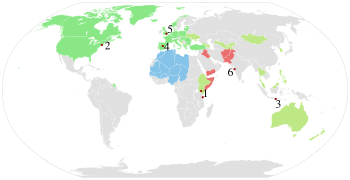

Photographs, clockwise from top left: U.S. servicemen boarding an aircraft at Bagram Air Base, Afghanistan; explosion of an Iraqi car bomb in Baghdad; a U.S. soldier and Afghan interpreter in Zabul Province, Afghanistan; Tomahawk missiles being fired from the warships at ISIL targets in the city of Raqqa, Syria Map: Countries with major military operations of the war on terror. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Main countries: | Main opponents: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

The war on terror, officially the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT),[3] is a global military campaign initiated by the United States following the September 11 attacks in 2001, and is the most recent global conflict spanning multiple wars. Some researchers and political scientists have argued that it replaced the Cold War.[4][5]

The main targets of the campaign are militant Islamist movements such as al-Qaeda, Taliban and their allies. Other major targets included the Ba'athist regime in Iraq, which was deposed in an invasion in 2003, and various militant factions that fought during the ensuing insurgency. Following its territorial expansion in 2014, the Islamic State also emerged as a key adversary of the United States. Regarding al-Qaeda's recent status, then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stated in 2021, "Al-Qaeda has a new base of operations: it is the Islamic Republic of Iran."[6] Al-Qaeda's de facto leader, Saif al-Adel, is currently believed to be living in Iran.[7]

The "war on terror" uses war as a metaphor to describe a variety of actions which fall outside the traditional definition of war. U.S. president George W. Bush first used the term "war on terrorism" on 16 September 2001,[8][9] and then "war on terror" a few days later in a formal speech to Congress.[10][11] Bush indicated the enemy of the war on terror as "a radical network of terrorists and every government that supports them".[11][12] The initial conflict was aimed at al-Qaeda, with the main theater in Afghanistan and Pakistan, a region that would later be referred to as "AfPak".[13] The term "war on terror" was immediately criticized by individuals including Richard Myers, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and eventually more nuanced terms came to be used by the Bush administration to define the campaign.[14] While "war on terror" was never used as a formal designation of U.S. operations,[15] a Global War on Terrorism Service Medal was and is issued by the U.S. Armed Forces.

As of 2024, various global operations in the campaign are ongoing, including a U.S. military intervention in Somalia.[16][17] Although the major wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have ended, the Israel–Hamas war and its spillover across the Middle East have led to renewed debate on whether a new phase of the war on terror had begun.[18][19][20] According to the Costs of War Project, the post-9/11 wars of the campaign have displaced 38 million people, the second largest number of forced displacements of any conflict since 1900,[21] and caused more than 4.5 million deaths (direct and indirect) in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Philippines, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria and Yemen. They also estimate that it has cost the US Treasury over $8 trillion.[22][23][24][2]

While support for the "war on terror" was high among the American public during its initial years, it had become deeply unpopular by the late 2000s.[25][26] Controversy over the war has focused on its morality, casualties, and continuity, with critics questioning government measures that infringed civil liberties and human rights.[27] Critics have notably described the Patriot Act as "Orwellian" due to its substantial expansion of the federal government's surveillance powers.[28][29] Controversial practices of coalition forces have been condemned, including drone warfare, surveillance, torture, extraordinary rendition and various war crimes.[30][31][32] The participating governments have been criticized for implementing authoritarian measures, repressing minorities,[33][34] fomenting Islamophobia globally,[35] and causing negative impacts to health and environment.[36][37][38] Security analysts assert that there is no military solution to the conflict, pointing out that terrorism is not an identifiable enemy, and have emphasized the importance of negotiations and political solutions to resolve the underlying roots of the crises.[39]

Etymology

The phrase war on terror was used to refer specifically to the military campaign led by the United States, the United Kingdom, and allied countries against organizations and regimes identified by them as terrorist, and usually excludes other independent counter-terrorist operations and campaigns such as those by Russia and India. The conflict has also been referred to by other names, such as "World War IV",[40] "World War III",[41] "Bush's War on Terror",[42] "The Long War",[43][44] "The Forever War",[45] "The Global War on Terror",[46] "The War Against al-Qaeda",[47] or "The War of Terror".[48]

Use of phrase and its development

The phrase "war against terrorism" existed in North American popular culture and U.S. political parlance prior to the war on terror.[49][50] But it was not until the 11 September attacks that it emerged as a globally recognizable phrase and part of everyday lexicon. Tom Brokaw, having just witnessed the collapse of one of the towers of the World Trade Center, declared "Terrorists have declared war on [America]."[51] On 16 September 2001, at Camp David, U.S. president George W. Bush used the phrase war on terrorism in an ostensibly unscripted comment when answering a journalist's question about the impact of enhanced law enforcement authority given to the U.S. surveillance agencies on Americans' civil liberties:

"This is a new kind of—a new kind of evil. And we understand. And the American people are beginning to understand. This crusade, this war on terrorism is going to take a while. And the American people must be patient. I'm going to be patient."[8][52]

The reference to Crusades became subject to heavy criticism due to its controversial connotations in the Muslim world and historical Muslim-Christian relations.[53] On 20 September 2001, during a televised address to a joint session of Congress, George Bush said, "Our war on terror begins with al Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated."[54][11] Both the term and the policies it denotes have been a source of ongoing controversy, as various critics and organizations like Amnesty International have argued that it has been used to justify unilateral preventive war, human rights abuses and other violations of international law.[55][56]

The political theorist Richard Jackson has argued that "the 'war on terrorism' [...] is simultaneously a set of actual practices—wars, covert operations, agencies, and institutions—and an accompanying series of assumptions, beliefs, justifications, and narratives—it is an entire language or discourse".[57] Jackson cites, among many examples, a statement by John Ashcroft that "the attacks of September 11 drew a bright line of demarcation between the civil and the savage".[58]

Administration officials also described "terrorists" as hateful, treacherous, barbarous, mad, twisted, perverted, without faith, parasitical, inhuman, and, most commonly, evil.[59] Americans, in contrast, were described as brave, loving, generous, strong, resourceful, heroic, and respectful of human rights.[60] Denouncing the remarks of George W. Bush, Osama Bin Laden stated during an interview in 21 October 2001:

"The events proved the extent of terrorism that America exercises in the world. Bush stated that the world has to be divided in two: Bush and his supporters, and any country that doesn't get into the global crusade is with the terrorists. What terrorism is clearer than this? Many governments were forced to support this "new terrorism."[61]

Decline of phrase's usage by U.S. government

In April 2007, the British government announced publicly that it was abandoning the use of the phrase "war on terror" as they found it to be less than helpful.[62] This was explained more recently by Lady Eliza Manningham-Buller. In her 2011 Reith lecture, the former head of MI5 said that the 9/11 attacks were "a crime, not an act of war. So I never felt it helpful to refer to a war on terror."[63]

U.S. president Barack Obama rarely used the term, but in his inaugural address on 20 January 2009, he stated: "Our nation is at war, against a far-reaching network of violence and hatred."[64] In March 2009 the Defense Department officially changed the name of operations from "Global War on Terror" to "Overseas Contingency Operation" (OCO).[65] In March 2009, the Obama administration requested that Pentagon staff members avoid the use of the term and instead to use "Overseas Contingency Operation".[65] Basic objectives of the Bush administration "war on terror", such as targeting al Qaeda and building international counterterrorism alliances, remain in place.[66][67]

Abandonment of phrase

In May 2010, the Obama administration published a report outlining its National Security Strategy. The document dropped the Bush-era phrase "global war on terror" and reference to "Islamic extremism," and stated, "This is not a global war against a tactic—terrorism, or a religion—Islam. We are at war with a specific network, al-Qaeda, and its terrorist affiliates who support efforts to attack the United States, our allies, and partners."[68]

Usage of the term "war on terror" was initially discontinued in May 2010[68] and again in May 2013.[69] On 23 May 2013, U.S. President Barack Obama announced that the "war on terrorism" was over,[70][71] saying that the U.S. would not wage war against a tactic but would instead focus on a specific group of terrorist networks.[72][73] Other American military campaigns during the 2010s have also been considered part of the "war on terror" by individuals and the media.[74] The rise of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria during 2014–2015 led to the global Operation Inherent Resolve, and an international campaign to destroy the terrorist organization. This was considered to be another campaign of the "war on terror".[74]

In December 2012, Jeh Johnson, the General Counsel of the Department of Defense, speaking at Oxford University, stated that the war against al-Qaeda would end when the terrorist group had been weakened so that it was no longer capable of "strategic attacks" and had been "effectively destroyed." At that point, the war would no longer be an armed conflict under international law,[75] and the military fight could be replaced by a law enforcement operation.[76]

In May 2013, two years after the assassination of Osama bin Laden, Barack Obama delivered a speech that employed the term global war on terror put in quotation marks (as officially transcribed by the White House): "Now, make no mistake, terrorists still threaten our nation. ... In Afghanistan, we will complete our transition to Afghan responsibility for that country's security. ... Beyond Afghanistan, we must define our effort not as a boundless 'global war on terror,' but rather as a series of persistent, targeted efforts to dismantle specific networks of violent extremists that threaten America. In many cases, this will involve partnerships with other countries." Nevertheless, in the same speech, in a bid to emphasize the legality of military actions undertaken by the U.S., noting that Congress had authorised the use of force, he went on to say, "Under domestic law, and international law, the United States is at war with al Qaeda, the Taliban, and their associated forces. We are at war with an organization that right now would kill as many Americans as they could if we did not stop them first. So this is a just war—a war waged proportionally, in last resort, and in self-defense."[69][77]

Nonetheless, the use of the phrase "war on terror" persists in U.S. politics. In 2017, for example, U.S. Vice President Mike Pence called the 1983 Beirut barracks bombing "the opening salvo in a war that we have waged ever since—the global war on terror."[78]

Background

Precursor to 11 September attacks

In May 1996, the group World Islamic Front for Jihad Against Jews and Crusaders (WIFJAJC), sponsored by Osama bin Laden (and later re-formed as al-Qaeda),[79][80] started forming a large base of operations in Afghanistan, where the Islamist extremist regime of the Taliban had seized power earlier in the year.[81] In August 1996, Bin Laden declared jihad against the United States.[82] In February 1998, Osama bin Laden signed a fatwa, as head of al-Qaeda, declaring war on the West and Israel;[83][84] in May al-Qaeda released a video declaring war on the U.S. and the West.[85][86]

On 7 August 1998, al-Qaeda struck the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, killing 224 people, including 12 Americans.[87] In retaliation, U.S. President Bill Clinton launched Operation Infinite Reach, a bombing campaign in Sudan and Afghanistan against targets the U.S. asserted were associated with WIFJAJC,[88][89] although others have questioned whether a pharmaceutical plant in Sudan was used as a chemical warfare facility. The plant produced much of the region's antimalarial drugs[90] and around 50% of Sudan's pharmaceutical needs.[91] The strikes failed to kill any leaders of WIFJAJC or the Taliban.[90]

Next came the 2000 millennium attack plots, which included an attempted bombing of Los Angeles International Airport. On 12 October 2000, the USS Cole bombing occurred near the port of Yemen, and 17 U.S. Navy sailors were killed.[92]

11 September attacks

On the morning of 11 September 2001, nineteen men hijacked four jet airliners, all of them bound for California. Once the hijackers assumed control of the jet airliners, they told the passengers that they had a bomb on board and would spare the lives of passengers and crew once their demands were met—no passenger and crew actually suspected that they would use the jet airliners as suicide weapons since it had never happened before in history, and many previous hijacking attempts had been resolved with the passengers and crew escaping unharmed after obeying the hijackers.[93][94] The hijackers—members of al-Qaeda's Hamburg cell[95]—intentionally crashed two jet airliners into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City. Both buildings collapsed within two hours from fire damage related to the crashes, destroying nearby buildings and damaging others. The hijackers crashed a third jet airliner into the Pentagon in Arlington County, Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C. The fourth jet airliner crashed into a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, after some of its passengers and flight crew attempted to retake control of the jet airliners, which the hijackers had redirected toward Washington, D.C., to target the White House or the U.S. Capitol. None of the flights had any survivors. A total of 2,977 victims and the 19 hijackers perished in the attacks.[96] Fifteen of the nineteen were citizens of Saudi Arabia, and the others were from the United Arab Emirates (2), Egypt, and Lebanon.[97]

On 13 September, for the first time ever, NATO invoked Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, which commits each member state to consider an armed attack against one member state to be an armed attack against them all.[98] The invocation of Article 5 led to Operation Eagle Assist and Operation Active Endeavour. On 18 September 2001, President Bush signed the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists passed by Congress a few days prior; the authorization is still active to this day and has been used to justify numerous military actions.

U.S. objectives

Major terrorist attacks by al-Qaeda and affiliated groups: (as of 2011) 1. 1998 United States embassy bombings • 2. September 11 attacks • 3. 2002 Bali bombings • 4. 2004 Madrid bombings • 5. 2005 London bombings • 6. 2008 Mumbai attacks

Major terrorist attacks by al-Qaeda and affiliated groups: (as of 2011) 1. 1998 United States embassy bombings • 2. September 11 attacks • 3. 2002 Bali bombings • 4. 2004 Madrid bombings • 5. 2005 London bombings • 6. 2008 Mumbai attacksThe Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists or "AUMF" was made law on 14 September 2001, to authorize the use of United States Armed Forces against those responsible for 11 September attacks. It authorized the President to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on 11 September 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or individuals. Congress declares this is intended to constitute specific statutory authorization within the meaning of section 5(b) of the War Powers Resolution of 1973.

The George W. Bush administration defined the following objectives in the war on terror:[99]

- Defeat terrorists such as Osama bin Laden, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and destroy their organizations

- Identify, locate and demolish terrorists along with their organizations

- Reject sponsorship, support and sanctuary to terrorists

- End the state sponsorship of terrorism

- Establish and maintain an international standard of responsibility concerning combating terrorism

- Strengthen and maintain the international effort to combat terrorism

- Function with willing and able states

- Enable weak states

- Persuade reluctant states

- Compel unwilling states

- Intervene and dismantle material support for terrorists

- Abolish terrorist sanctuaries and havens

- Reduce the underlying conditions that terrorists seek to exploit

- Establish partnerships with the international community to strengthen weak states and prevent (re)emergence of terrorism

- Win the war of ideals

- Protect U.S. citizens and interests at home and abroad

- Integrate the National Strategy for Homeland Security

- Attain domain awareness

- Enhance measures to ensure the integrity, reliability, and availability of critical, physical, and information-based infrastructures at home and abroad

- Implement measures to protect U.S. citizens abroad

- Ensure an integrated incident management capacity

The 2001 AUMF has authorized US President to launch military operations across the world without any congressional oversight or transparency. Between 2018 and 2020 alone, US forces initiated what it labelled "counter-terror" activities in 85 countries. Of these, the 2001 AUMF has been used to launch classified military campaigns in at least 22 countries.[100][101] The 2001 AUMF has been widely perceived as a bill that grants the President powers to unilaterally wage perpetual "world wide wars".[102]

Timeline

Operation Enduring Freedom

Operation Enduring Freedom is the official name used by the Bush administration for the War in Afghanistan, together with three smaller military actions, under the umbrella of the global war on terror. These global operations are intended to seek out and destroy any al-Qaeda fighters or affiliates. Originally, the campaign was named "Eternal Justice" but due to widespread controversy and condemnation in the Muslim world, the phrasing was changed to "Enduring Freedom".[53]

Afghanistan

On 20 September 2001, in the wake of the September 11 attacks, George W. Bush delivered an ultimatum to the Taliban government of Afghanistan, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, to turn over Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda leaders operating in the country or face attack.[11] The Taliban demanded evidence of bin Laden's link to 11 September attacks and, if such evidence warranted a trial, they offered to handle such a trial in an Islamic Court.[103]

Subsequently, in October 2001, U.S. forces (with UK and coalition allies) invaded Afghanistan to oust the Taliban regime. On 7 October 2001, the official invasion began with British and U.S. forces conducting airstrike campaigns over enemy targets. Shortly after, Bush rejected a Taliban offer to hand over bin Laden on the condition the bombing campaign was halted,[104] and by mid-November, Kabul, the capital city of Afghanistan, fell. The remaining al-Qaeda and Taliban remnants fell back to the rugged mountains of eastern Afghanistan, mainly Tora Bora. In December, Coalition forces (the U.S. and its allies) fought within that region. It is believed that Osama bin Laden escaped into Pakistan during the battle.[105][106]

In March 2002, the U.S. and other NATO and non-NATO forces launched Operation Anaconda with the goal of destroying any remaining al-Qaeda and Taliban forces in the Shah-i-Kot Valley and Arma Mountains of Afghanistan. The Taliban suffered heavy casualties and evacuated the region.[107]

The Taliban regrouped in western Pakistan and began to unleash an insurgent-style offensive against Coalition forces in late 2002.[108] Throughout southern and eastern Afghanistan, firefights broke out between the surging Taliban and Coalition forces. Coalition forces responded with a series of military offensives and an increase of troops in Afghanistan. In February 2010, Coalition forces launched Operation Moshtarak in southern Afghanistan along with other military offensives in the hopes that they would destroy the Taliban insurgency once and for all.[109] Peace talks were also underway between Taliban affiliated fighters and Coalition forces.[110]

In September 2014, Afghanistan and the United States signed a security agreement, which allowed the United States and NATO forces to remain in Afghanistan until at least 2024.[111] However, on 29 February 2020, the United States and the Taliban signed a conditional peace deal in Doha which required that US troops withdraw from Afghanistan within 14 months so long as the Taliban cooperated with the terms of the agreement not to "allow any of its members, other individuals or groups, including Al Qaeda, to use the soil of Afghanistan to threaten the security of the United States and its allies".[112][113] The Afghan government was not a party to the deal and rejected its terms regarding release of prisoners.[114] After Joe Biden became president, he moved back the target withdrawal date to 31 August 2021.[115] On 15 August 2021, the Afghan capital Kabul fell to a surprisingly effective Taliban offensive, ending the war in Afghanistan. The US military and NATO troops took control of Kabul's Hamid Karzai International Airport for use in Operation Allies Refuge and the large-scale evacuation of foreign citizens and certain vulnerable Afghans, executed in cooperation with the Taliban.[116][117][118][119][120]

On 30 August 2021, the United States completed its hasty withdrawal of its military from Afghanistan. The withdrawal was heavily criticized both domestically and abroad for being chaotic and haphazard,[121][122] as well as for lending more momentum to the Taliban offensive.[123] However, many European countries followed suit, including Britain, Germany, Italy, and Poland.[124][125] Despite evacuating over 120,000 people, the large-scale evacuation has also been criticized for leaving behind hundreds of American citizens, residents, and family members.[126]

International Security Assistance Force

The NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) was created in December 2001 to assist the Afghan Transitional Administration and the first post-Taliban elected government. With a renewed Taliban insurgency, it was announced in 2006 that ISAF would replace the U.S. troops in the province as part of Operation Enduring Freedom.

The British 16th Air Assault Brigade (later reinforced by Royal Marines) formed the core of the force in southern Afghanistan, along with troops and helicopters from Australia, Canada and the Netherlands. The initial force consisted of roughly 3,300 British, 2,000 Canadian, 1,400 from the Netherlands and 240 from Australia, along with special forces from Denmark and Estonia and small contingents from other nations. The monthly supply of cargo containers through Pakistani route to ISAF in Afghanistan is over 4,000 costing around 12 billion in Pakistani Rupees.[127][128][129][130][131]

Philippines

In January 2002, the United States Special Operations Command, Pacific deployed to the Philippines to advise and assist the Armed Forces of the Philippines in combating Filipino Islamist groups.[132] The operations were mainly focused on removing the Abu Sayyaf group and Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) from their stronghold on the island of Basilan.[citation needed] The second portion of the operation was conducted as a humanitarian program called "Operation Smiles". The goal of the program was to provide medical care and services to the region of Basilan as part of a "Hearts and Minds" program.[133]

Joint Special Operations Task Force – Philippines disbanded in June 2014,[134] ending a successful 12-year mission.[135] After JSOTF-P had disbanded, as late as November 2014, American forces continued to operate in the Philippines under the name "PACOM Augmentation Team", until 24 February 2015.[136][137] On 1 September 2017, US Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis designated Operation Pacific Eagle – Philippines (OPE-P) as a contingency operation to support the Philippine government and the military in their efforts to isolate, degrade, and defeat the affiliates of ISIL (collectively referred to as ISIL-Philippines or ISIL-P) and other terrorist organisations in the Philippines.[138] By 2018, American operations within the Philippines against terrorist groups involved as many as 300 advisers.[139]

Trans-Sahara (Northern Africa)

Operation Enduring Freedom – Trans Sahara (OEF-TS), now Operation Juniper Shield, is the name of the military operation conducted by the U.S. and partner nations in the Sahara/Sahel region of Africa, consisting of counter-terrorism efforts and policing of arms and drug trafficking across central Africa.

The conflict in northern Mali began in January 2012 with radical Islamists (affiliated to al-Qaeda) advancing into northern Mali. The Malian government had a hard time maintaining full control over their country. The fledgling government requested support from the international community on combating the Islamic militants. In January 2013, France intervened on behalf of the Malian government's request and deployed troops into the region. They launched Operation Serval on 11 January 2013, with the hopes of dislodging the al-Qaeda affiliated groups from northern Mali.[140]

Horn of Africa and the Red Sea

Operation Enduring Freedom – Horn of Africa is an extension of Operation Enduring Freedom. Unlike other operations contained in Operation Enduring Freedom, OEF-HOA does not have a specific organization as a target. OEF-HOA instead focuses its efforts to disrupt and detect militant activities in the region and to work with willing governments to prevent the reemergence of militant cells and activities.[141]

In October 2002, the Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA) was established in Djibouti at Camp Lemonnier.[142] It contains approximately 2,000 personnel including U.S. military and special operations forces (SOF) and coalition force members, Combined Task Force 150 (CTF-150).

Task Force 150 consists of ships from a shifting group of nations, including Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Pakistan, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. The primary goal of the coalition forces is to monitor, inspect, board and stop suspected shipments from entering the Horn of Africa region and affecting the United States' Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Included in the operation is the training of selected armed forces units of the countries of Djibouti, Kenya and Ethiopia in counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency tactics. Humanitarian efforts conducted by CJTF-HOA include rebuilding of schools and medical clinics and providing medical services to those countries whose forces are being trained.

The program expands as part of the Trans-Saharan Counterterrorism Initiative as CJTF personnel also assist in training the armed forces of Chad, Niger, Mauritania and Mali. However, the war on terror does not include Sudan, where over 400,000 have died in an ongoing civil war.

On 1 July 2006, a Web-posted message purportedly written by Osama bin Laden urged Somalis to build an Islamic state in the country and warned western governments that the al-Qaeda network would fight against them if they intervened there.[143]

The Prime Minister of Somalia claimed that three "terror suspects" from the 1998 United States embassy bombings are being sheltered in Kismayo.[144] On 30 December 2006, al-Qaeda deputy leader Ayman al-Zawahiri called upon Muslims worldwide to fight against Ethiopia and the TFG in Somalia.[145]

On 8 January 2007, the U.S. launched the Battle of Ras Kamboni by bombing Ras Kamboni using AC-130 gunships.[146]

On 14 September 2009, U.S. Special Forces killed two men and wounded and captured two others near the Somali village of Baarawe. Witnesses claim that helicopters used for the operation launched from French-flagged warships, but that could not be confirmed. A Somali-based al-Qaida affiliated group, the Al-Shabaab, has verified the death of "sheik commander" Saleh Ali Saleh Nabhan along with an unspecified number of militants.[147] Nabhan, a Kenyan, was wanted in connection with the 2002 Mombasa attacks.[148]

Iraq War

2002 State of the Union Address

During his 2002 State of the Union Address, George W. Bush accused North Korea, Iran and Iraq of propping up state-sponsored terrorism and pursuing Weapons of Mass Destruction. These countries were portrayed as a global threat and categorised under the terminology referred to as "Axis of evil".[149] Regarding Iraq, Bush alleged:

"Iraq continues to flaunt its hostility toward America and to support terror. The Iraqi regime has plotted to develop anthrax and nerve gas and nuclear weapons for over a decade. This is a regime that has already used poison gas to murder thousands of its own citizens, leaving the bodies of mothers huddled over their dead children. This is a regime that agreed to international inspections, then kicked out the inspectors. This is a regime that has something to hide from the civilized world."[150]

Prelude

In October 2002, United States Congress passed the "Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002", which empowered the U.S. president to order military attack against Iraq.[151][152] On 5 February 2003, Secretary of State Colin Powell made a presentation before the UN Security Council which claimed to implicate Iraq in building a secret WMD program and having ties to Al-Qaeda.[153]

On 17 March 2003, Bush issued an ultimatum to Saddam Hussein and his two sons to flee Iraq within a 48-hour deadline or else face "military conflict".[154] Justifying his policy Bush declared:

"Terrorists and terror states do not reveal these threats with fair notice, in formal declarations—and responding to such enemies only after they have struck first is not self-defense, it is suicide. The security of the world requires disarming Saddam Hussein now."[154]

Invasion of Iraq

The Iraq War began in March 2003 with an air campaign, which was immediately followed by a U.S.-led ground invasion.[155][156] The Bush administration cited UNSC Resolution 1441, which warned of "serious consequences" for violations such as Iraq possessing weapons of mass destruction. The Bush administration also stated the Iraq War was part of the war on terror, a claim later questioned and contested. Iraq had been listed as a state sponsor of terrorism by the U.S. since 1990,[157] when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait.

The first ground attack came at the Battle of Umm Qasr on 21 March 2003, when a combined force of British, U.S. and Polish forces seized control of the port city of Umm Qasr.[158] Baghdad, Iraq's capital city, fell to U.S. troops in April 2003 and Saddam Hussein's government quickly dissolved.[159] On 1 May 2003, Bush announced that major combat operations in Iraq had ended.[160]

Iraqi Insurgency (2003–11)

However, an insurgency arose against the U.S.-led coalition and the newly developing Iraqi military and post-Saddam government. The rebellion, which included al-Qaeda-affiliated groups, led to many coalition casualties. Other elements of the insurgency were led by fugitive members of President Hussein's Ba'ath regime, which included Iraqi nationalists and pan-Arabists. Many insurgency leaders were Islamists and claimed to be fighting a religious war to reestablish the Islamic Caliphate of centuries past.[161] Saddam Hussein was captured by U.S. forces in December 2003 and was executed in 2006.

In 2004, the insurgent forces grew stronger. The U.S. launched offensives on insurgent strongholds in cities like Najaf and Fallujah.

In January 2007, President Bush presented a new strategy for Operation Iraqi Freedom based upon counter-insurgency theories and tactics developed by General David Petraeus. The Iraq War troop surge of 2007 was part of this "new way forward", which along with U.S. backing of Sunni groups it had previously sought to defeat has been credited with a widely recognized dramatic decrease in violence by up to 80%.[citation needed]

The war entered a new phase on 1 September 2010,[162] with the official end of U.S. combat operations.

War in Iraq (2013–17)

President Obama ordered the withdrawal of most troops in 2011, but began redeploying forces in 2014 to fight the Islamic State group.[163] As of July 2021, there were approximately 2,500 U.S. troops in Iraq, who continue to assist in the mission to combat the remnants of IS.[164]

Pakistan

Following 11 September attacks, former President of Pakistan Pervez Musharraf sided with the U.S. against the Taliban government in Afghanistan after an ultimatum by then U.S. President George W. Bush. Musharraf agreed to give the U.S. the use of three airbases for Operation Enduring Freedom. United States Secretary of State Colin Powell and other U.S. administration officials met with Musharraf. On 19 September 2001, Musharraf addressed the people of Pakistan and stated that, while he opposed military tactics against the Taliban, Pakistan risked being endangered by an alliance of India and the U.S. if it did not cooperate. In 2006, Musharraf testified that this stance was pressured by threats from the U.S., and revealed in his memoirs that he had "war-gamed" the United States as an adversary and decided that it would end in a loss for Pakistan.[165]

On 12 January 2002, Musharraf gave a speech against Islamic extremism. He unequivocally condemned all acts of terrorism and pledged to combat Islamic extremism and lawlessness within Pakistan itself. He stated that his government was committed to rooting out extremism and made it clear that the banned militant organizations would not be allowed to resurface under any new name. He said, "the recent decision to ban extremist groups promoting militancy was taken in the national interest after thorough consultations. It was not taken under any foreign influence".[166]

In 2002, the Musharraf-led government took a firm stand against the jihadi organizations and groups promoting extremism, and arrested Maulana Masood Azhar, head of the Jaish-e-Mohammed, and Hafiz Muhammad Saeed, chief of the Lashkar-e-Taiba, and took dozens of activists into custody. An official ban was imposed on the groups on 12 January.[167] Later that year, the Saudi born Zayn al-Abidn Muhammed Hasayn Abu Zubaydah was arrested by Pakistani officials during a series of joint U.S.–Pakistan raids. Zubaydah is said to have been a high-ranking al-Qaeda official with the title of operations chief and in charge of running al-Qaeda training camps.[168] Other prominent al-Qaeda members were arrested in the following two years, namely Ramzi bin al-Shibh, who is known to have been a financial backer of al-Qaeda operations, and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who at the time of his capture was the third highest-ranking official in al-Qaeda and had been directly in charge of the planning for 11 September attacks.

In 2004, the Pakistan Army launched a campaign in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan's Waziristan region, sending in 80,000 troops. The goal of the conflict was to remove the al-Qaeda and Taliban forces in the area.

After the fall of the Taliban regime, many members of the Taliban resistance fled to the Northern border region of Afghanistan and Pakistan where the Pakistani army had previously little control. With the logistics and air support of the United States, the Pakistani Army captured or killed numerous al-Qaeda operatives such as Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, wanted for his involvement in the USS Cole bombing, the Bojinka plot, and the killing of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl.

The United States has carried out a campaign of drone attacks on targets all over the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. However, the Pakistani Taliban still operates there. To this day it is estimated that 15 U.S. soldiers were killed while fighting al-Qaeda and Taliban remnants in Pakistan since the war on terror began.[169]

Osama bin Laden, his wife, and son, were all killed on 2 May 2011, during a raid conducted by the United States special operations forces in Abbottabad, Pakistan.[170]

The use of drones by the Central Intelligence Agency in Pakistan to carry out operations associated with the global war on terror sparks debate over sovereignty and the laws of war. The U.S. Government uses the CIA rather than the U.S. Air Force for strikes in Pakistan to avoid breaching sovereignty through military invasion. The United States was criticized by[according to whom?] a report on drone warfare and aerial sovereignty for abusing the term 'global war on terror' to carry out military operations through government agencies without formally declaring war.

After 11 September attacks, U.S. economic and security aid to Pakistan spiked considerably. With the authorization of the Enhanced Partnership for Pakistan Act, Pakistan was granted US$7.5 billion over five years from FY2010–FY2014.[171]

Yemen

The United States has also conducted a series of military strikes on al-Qaeda militants in Yemen since the war on terror began.[172] Yemen has a weak central government and a powerful tribal system that leaves large lawless areas open for militant training and operations. Al-Qaeda has a strong presence in the country.[173] On 31 March 2011, AQAP declared the Al-Qaeda Emirate in Yemen after its captured most of Abyan Governorate.[174]

The U.S., in an effort to support Yemeni counter-terrorism efforts, has increased their military aid package to Yemen from less than $11 million in 2006 to more than $70 million in 2009, as well as providing up to $121 million for development over the next three years.[175]

In 2024, the U.S. has re-designated the Houthis as Specially Designated Global Terrorists in the context of the Red Sea crisis, Operation Prosperity Guardian and Operation Poseidon Archer. The military campaign is still ongoing.[176] It has been argued that the Houthis have team up with Al-Qaeda since 2023.[177] Since then, this alliance remains ongoing under the context of the Red Sea crisis.[178]

Other military operations

Operation Inherent Resolve (Syria and Iraq)

The Obama administration began to re-engage in Iraq with a series of airstrikes aimed at ISIL starting on 10 August 2014.[179] On 9 September 2014, President Obama said that he had the authority he needed to take action to destroy the militant group known as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, citing the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force Against Terrorists, and thus did not require additional approval from Congress.[180] The following day on 10 September 2014 President Barack Obama made a televised speech about ISIL, which he stated: "Our objective is clear: We will degrade, and ultimately destroy, ISIL through a comprehensive and sustained counter-terrorism strategy".[181] Obama has authorized the deployment of additional U.S. Forces into Iraq, as well as authorizing direct military operations against ISIL within Syria.[181] On the night of 21/22 September the United States, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the UAE, Jordan and Qatar started air attacks against ISIL in Syria.[182]

In October 2014, it was reported that the U.S. Department of Defense considers military operations against ISIL as being under Operation Enduring Freedom in regards to campaign medal awarding.[183] On 15 October, the military intervention became known as "Operation Inherent Resolve".[184]

Islamic State of Lanao and the Battle of Marawi

With the rise of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), jihadist offshoots sprung up in regions around the world, including the Philippines. The Maute group, composed of former Moro Islamic Liberation Front guerrillas and foreign fighters led by Omar Maute, the alleged founder of a Dawlah Islamiya, declared loyalty to ISIL and began clashing with Philippine security forces and staging bombings. On 23 May 2017, the group attacked the city of Marawi, resulting in the bloody Battle of Marawi that lasted 5 months. After the decisive battle, remnants of the group were reportedly still recruiting in 2017 and 2018.[185][186]

Libyan War

NBC News reported that in mid-2014, ISIL had about 1,000 fighters in Libya. Taking advantage of a power vacuum in the center of the country, far from the major cities of Tripoli and Benghazi, ISIL expanded rapidly over the next 18 months. Local militants were joined by jihadists from the rest of North Africa, the Middle East, Europe and the Caucasus. The force absorbed or defeated other Islamist groups inside Libya and the central ISIL leadership in Raqqa, Syria, began urging foreign recruits to head for Libya instead of Syria. ISIL seized control of the coastal city of Sirte in early 2015 and then began to expand to the east and south. By the beginning of 2016, it had effective control of 120 to 150 miles of coastline and portions of the interior and had reached Eastern Libya's major population center, Benghazi. In spring 2016, AFRICOM estimated that ISIL had about 5,000 fighters in its stronghold of Sirte.[187]

However, the indigenous rebel groups who had staked their claims to Libya and turned their weapons on ISIL—with the help of airstrikes by Western forces, including U.S. drones, the Libyan population resented the outsiders who wanted to establish a fundamentalist regime on their soil. Militias loyal to the new Libyan unity government, plus a separate and rival force loyal to a former officer in the Gaddafi regime, launched an assault on ISIL outposts in Sirte and the surrounding areas that lasted for months. According to U.S. military estimates, ISIL ranks shrank to somewhere between a few hundred and 2,000 fighters. In August 2016, the U.S. military began airstrikes that, along with continued pressure on the ground from the Libyan militias, pushed the remaining ISIL fighters back into Sirte. In all, U.S. drones and planes hit ISIL nearly 590 times, the Libyan militias reclaimed the city in mid-December.[187] On 18 January 2017, ABC News reported that two USAF B-2 bombers struck two ISIL camps 28 miles (45 km) south of Sirte, the airstrikes targeted between 80 and 100 ISIL fighters in multiple camps, an unmanned aircraft also participated in the airstrikes. NBC News reported that as many as 90 ISIL fighters were killed in the strike, a U.S. defense official said that "This was the largest remaining ISIL presence in Libya," and that "They have been largely marginalized, but I am hesitant to say they have been eliminated in Libya."[187]

American military intervention in Cameroon

In October 2015, the U.S. began deploying 300 soldiers[188] to Cameroon, with the invitation of the Cameroonian government, to support African forces in a non-combat role in their fight against ISIL insurgency in that country. The troops' primary missions will revolve around providing intelligence support to local forces as well as conducting reconnaissance flights.[189]

Operation Active Endeavour

Operation Active Endeavour was a naval operation of NATO started in October 2001 in response to 11 September attacks. It operated in the Mediterranean and was designed to prevent the movement of militants or weapons of mass destruction and to enhance the security of shipping in general.[190]

Fighting in Kashmir

In a 'Letter to American People' written by Osama bin Laden in 2002, he stated that one of the reasons he was fighting America is because of its support of India on the Kashmir issue.[191][192] Indian sources claimed that in 2006, al-Qaeda claimed they had established a wing in Kashmir; this worried the Indian government.[193] India also argued that al-Qaeda has strong ties with the Kashmir militant groups Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed in Pakistan.[194] While on a visit to Pakistan in January 2010, U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates stated that al-Qaeda was seeking to destabilize the region and planning to provoke a nuclear war between India and Pakistan.[195]

In September 2009, a U.S. drone strike reportedly killed Ilyas Kashmiri, who was the chief of Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami, a Kashmiri militant group associated with al-Qaeda.[196][197] Kashmiri was described by Bruce Riedel as a 'prominent' al-Qaeda member,[198] while others described him as the head of military operations for al-Qaeda.[199] Waziristan had now become the new battlefield for Kashmiri militants, who were now fighting NATO in support of al-Qaeda.[200] On 8 July 2012, Al-Badar Mujahideen, a breakaway faction of Kashmir centric terror group Hizbul Mujahideen, on the conclusion of their two-day Shuhada Conference called for a mobilization of resources for continuation of jihad in Kashmir.[201] In June 2021, an air force station in Jammu (in India-administered Kashmir) was attacked by drone. Investigators were uncertain whether a state or non-state actor initiated the attack.[202][203]

Anti-terror campaigns by other powers

For decades, Israel, a key ally of the United States in the region of the Middle East, has engaged in its own war on terror against Hamas, Hezbollah, and other Iranian-backed insurgent groups. Although Israel did not directly participate in the 2003 invasion of Iraq, it reportedly urged the U.S. not to delay an attack on Saddam Hussein.[204] Before the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, Israeli intelligence reportedly provided information to Washington.[205] Israel launched a 34-day military conflict against Hezbollah in Lebanon, northern Israel and the Golan Heights during mid-2006.[206] Following the October 7 attack, Israel declared the still ongoing Israel-Hamas War, leading to a ground invasion on October 27 with the stated goals of destroying Hamas and freeing hostages.[207][208][209][210][211]

Colombia has also engaged on its own War on Terror,[212][213] as terrorism by both guerrillas and paramilitaries remains a major concern in the country since the escalation of armed violence in the 2000s in the context of the Colombian conflict.[214] Álvaro Uribe's Presidency, in particular, was marked by a significant focus on counter-terrorism and counterinsurgency. The counterterrorism measures of Plan Colombia acquired further expansion during the presidency of George W. Bush and an important focus on national security after the events of 9/11, as the threat of global terrorism received greater attention.[215]

In the 2010s, China has also been engaged in its own war on terror, predominantly a domestic campaign in response to violent actions by Uyghur separatist movements in the Xinjiang conflict.[216] This campaign was widely criticized in international media due to the perception that it unfairly targets and persecutes Chinese Muslims,[217] potentially resulting in a negative backlash from China's predominantly Muslim Uighur population. Xi Jinping's government has imprisoned up to two million Uyghurs and other Muslim ethnic minorities in Xinjiang internment camps, where they are reportedly subject to abuse and torture.[218][219]

Russia has also been engaged on its own, also largely internally focused, counter-terrorism campaign often termed a war on terror, during the Second Chechen War, the Insurgency in the North Caucasus, and the Russian military intervention in the Syrian Civil War.[220] Like China's war on terror, Russia has also been focused on separatist and Islamist movements that use political violence to achieve their ends.[221] However, Putin's Russia's disinformation and actions, as well as its inaction towards groups like Hamas, Hezbollah and the Taliban, have raised doubts about its commitment to the war on terror.[222]

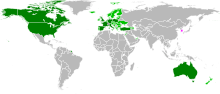

International military support

The invasion of Afghanistan is seen to have been the first action of this war, and initially involved forces from the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Afghan Northern Alliance. Since the initial invasion period, these forces were augmented by troops and aircraft from Australia, Canada, Denmark, France, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand and Norway among others. In 2006, there were about 33,000 troops in Afghanistan.

On 12 September 2001, less than 24 hours after 11 September attacks in New York City and Washington, D.C., NATO invoked Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty and declared the attacks to be an attack against all 19 NATO member countries. Australian Prime Minister John Howard also stated that Australia would invoke the ANZUS Treaty along similar lines.[223]

In the following months, NATO took a broad range of measures to respond to the threat of terrorism. On 22 November 2002, the member states of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC) decided on a Partnership Action Plan against Terrorism, which explicitly states, "[The] EAPC States are committed to the protection and promotion of fundamental freedoms and human rights, as well as the rule of law, in combating terrorism."[224] NATO started naval operations in the Mediterranean Sea designed to prevent the movement of terrorists or weapons of mass destruction as well as to enhance the security of shipping in general called Operation Active Endeavour.

Support for the U.S. cooled when America made clear its determination to invade Iraq in late 2002. Still, many of the "coalition of the willing" countries that unconditionally supported the U.S.-led military action have sent troops to Afghanistan, particular neighboring Pakistan, which has disowned its earlier support for the Taliban and contributed tens of thousands of soldiers to the conflict. Pakistan was also engaged in the Insurgency in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (a.k.a. Waziristan War or North-West Pakistan War). Supported by U.S. intelligence, Pakistan attempted to remove the Taliban insurgency and al-Qaeda element from the northern tribal areas.[225]

Post–9/11 events inside the United States

In addition to military efforts abroad, in the aftermath of 9/11, the Bush Administration increased domestic efforts to prevent future attacks. Various government bureaucracies that handled security and military functions were reorganized. A new cabinet-level agency called the United States Department of Homeland Security was created in November 2002 to lead and coordinate the largest reorganization of the U.S. federal government since the consolidation of the armed forces into the Department of Defense.[citation needed]

The Justice Department launched the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System for certain male non-citizens in the U.S., requiring them to register in person at offices of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

The USA PATRIOT Act of October 2001 dramatically reduces restrictions on law enforcement agencies' ability to search telephone, e-mail communications, medical, financial, and other records; eases restrictions on foreign intelligence gathering within the United States; expands the Secretary of the Treasury's authority to regulate financial transactions, particularly those involving foreign individuals and entities; and broadens the discretion of law enforcement and immigration authorities in detaining and deporting immigrants suspected of terrorism-related acts. The act also expanded the definition of terrorism to include domestic terrorism, thus enlarging the number of activities to which the USA PATRIOT Act's expanded law enforcement powers could be applied. A new Terrorist Finance Tracking Program monitored the movements of terrorists' financial resources (discontinued after being revealed by The New York Times). Global telecommunication usage, including those with no links to terrorism,[226] is being collected and monitored through the NSA electronic surveillance program. The Patriot Act is still in effect.

Political interest groups have stated that these laws remove important restrictions on governmental authority, and are a dangerous encroachment on civil liberties, possible unconstitutional violations of the Fourth Amendment. On 30 July 2003, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed the first legal challenge against Section 215 of the Patriot Act, claiming that it allows the FBI to violate a citizen's First Amendment rights, Fourth Amendment rights, and right to due process, by granting the government the right to search a person's business, bookstore, and library records in a terrorist investigation, without disclosing to the individual that records were being searched.[227] Also, governing bodies in many communities have passed symbolic resolutions against the act.

In a speech on 9 June 2005, Bush said that the USA PATRIOT Act had been used to bring charges against more than 400 suspects, more than half of whom had been convicted. Meanwhile, the ACLU quoted Justice Department figures showing that 7,000 people have complained of abuse of the Act.[citation needed]

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) began an initiative in early 2002 with the creation of the Total Information Awareness program, designed to promote information technologies that could be used in counter-terrorism. This program, facing criticism, has since been defunded by Congress.[citation needed]

By 2003, 12 major conventions and protocols were designed to combat terrorism. These were adopted and ratified by many states. These conventions require states to co-operate on principal issues regarding unlawful seizure of aircraft, the physical protection of nuclear materials, and the freezing of assets of militant networks.[228]

In 2005, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1624 concerning incitement to commit acts of terrorism and the obligations of countries to comply with international human rights laws.[229] Although both resolutions require mandatory annual reports on counter-terrorism activities by adopting nations, the United States and Israel have both declined to submit reports. In the same year, the United States Department of Defense and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a planning document, by the name "National Military Strategic Plan for the War on Terrorism", which stated that it constituted the "comprehensive military plan to prosecute the Global War on Terror for the Armed Forces of the United States...including the findings and recommendations of the 9/11 Commission and a rigorous examination with the Department of Defense".

On 9 January 2007, the House of Representatives passed a bill, by a vote of 299–128, enacting many of the recommendations of the 9/11 Commission The bill passed in the U.S. Senate,[230] by a vote of 60–38, on 13 March 2007 and it was signed into law on 3 August 2007 by President Bush. It became Public Law 110–53. In July 2012, U.S. Senate passed a resolution urging that the Haqqani Network be designated a foreign terrorist organization.[231]

The Office of Strategic Influence was secretly created after 9/11 for the purpose of coordinating propaganda efforts but was closed soon after being discovered. The Bush administration implemented the Continuity of Operations Plan (or Continuity of Government) to ensure that U.S. government would be able to continue in catastrophic circumstances.

Since 9/11, extremists made various attempts to attack the United States, with varying levels of organization and skill. For example, vigilant passengers aboard a transatlantic flight prevented Richard Reid, in 2001, and Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, in 2009, from detonating an explosive device.

Other terrorist plots have been stopped by federal agencies using new legal powers and investigative tools, sometimes in cooperation with foreign governments.[citation needed]

Such thwarted attacks include:

- The 2001 shoe bomb plot

- A plan to crash airplanes into the U.S. Bank Tower (aka Library Tower) in Los Angeles

- The 2003 plot by Iyman Faris to blow up the Brooklyn Bridge in New York City

- The 2004 Financial buildings plot, which targeted the International Monetary Fund and World Bank buildings in Washington, D.C., the New York Stock Exchange and other financial institutions

- The 2004 Columbus Shopping Mall Bombing Plot

- The 2006 Sears Tower plot

- The 2007 Fort Dix attack plot

- The 2007 John F. Kennedy International Airport attack plot

- The New York Subway Bombing Plot and 2010 Times Square car bombing attempt

The Obama administration promised the closing of the Guantanamo Bay detention camp, increased the number of troops in Afghanistan, and promised the withdrawal of its forces from Iraq.

Transnational actions

"Extraordinary rendition"

After 11 September attacks, the United States government commenced a program of illegal "extraordinary rendition", sometimes referred to as "irregular rendition" or "forced rendition", the government-sponsored abduction and extrajudicial transfer of a person from one country to transferee countries, with the consent of transferee countries.[235][236][237] The aim of extraordinary rendition is often conducting torture on the detainee that would be difficult to conduct in the U.S. legal environment, a practice known as torture by proxy. Starting in 2002, U.S. government rendered hundreds of illegal combatants for U.S. detention, and transported detainees to U.S. controlled sites as part of an extensive interrogation program that included torture.[238] Extraordinary rendition continued under the Obama administration, with targets being interrogated and subsequently taken to the US for trial.[239]

The United Nations considers one nation abducting the citizens of another a crime against humanity.[240] In July 2014 the European Court of Human Rights condemned the government of Poland for participating in CIA extraordinary rendition, ordering Poland to pay restitution to men who had been abducted, taken to a CIA black site in Poland, and tortured.[241][242][243]

Rendition to "Black Sites"

In 2005, The Washington Post and Human Rights Watch (HRW) published revelations concerning kidnapping of detainees by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency and their transport to "black sites", covert prisons operated by the CIA whose existence is denied by the US government. The European Parliament published a report connecting use of such secret detention Black Sites for detainees kidnapped as part of extraordinary rendition (See the European Parliament's investigation and report). Although some Black Sites have been known to exist inside European Union states, these detention centers violate the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the UN Convention Against Torture, treaties that all EU member states are bound to follow.[244][245][246] The U.S. had ratified the United Nations Convention Against Torture in 1994.[247]

According to ABC News two such facilities, in countries mentioned by Human Rights Watch, have been closed following the recent publicity with the CIA relocating the detainees. Almost all of these detainees were tortured as part of the "enhanced interrogation techniques" of the CIA.[248] Despite the closure of these sites, their legacies in certain countries continue to live on and haunt domestic politics.[249]

Criticism of U.S. media's withholding of coverage

Major American newspapers, such as The Washington Post, have been criticized for deliberately withholding publication of articles reporting locations of Black Sites. The Post defended its decision to suppress this news on the ground that such revelations "could open the U.S. government to legal challenges, particularly in foreign courts, and increase the risk of political condemnation at home and abroad." However, according to Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting "the possibility that illegal, unpopular government actions might be disrupted is not a consequence to be feared, however—it's the whole point of the U.S. First Amendment. ... Without the basic fact of where these prisons are, it's difficult if not impossible for 'legal challenges' or 'political condemnation' to force them to close." FAIR argued that the damage done to the global reputation of the United States by the continued existence of black-site prisons was more dangerous than any threat caused by the exposure of their locations.[250]

The complex at Stare Kiejkuty, a Soviet-era compound once used by German intelligence in World War II, is best known as having been the only Russian intelligence training school to operate outside the Soviet Union. Its prominence in the Soviet era suggests that it may have been the facility first identified—but never named—when the Washington Post's Dana Priest revealed the existence of the CIA's secret prison network in November 2005.[251]

The journalists who exposed this provided their sources and this information and documents were provided to The Washington Post in 2005. In addition, they also identified such Black Sites are concealed:

Former European and US intelligence officials indicate that the secret prisons across the European Union, first identified by the Washington Post, are likely not permanent locations, making them difficult to identify and locate. What some believe was a network of secret prisons was most probably a series of facilities used temporarily by the United States when needed, officials say. Interim "black sites"—secret facilities used for covert activities—can be as small as a room in a government building, which only becomes a black site when a prisoner is brought in for short-term detainment and interrogation.

The journalists went on to explain that "Such a site, sources say, would have to be near an airport." The airport in question is the Szczytno-Szymany International Airport.

In response to these allegations, former Polish intelligence chief, Zbigniew Siemiatkowski, embarked on a media blitz and claimed that the allegations were "... part of the domestic political battle in the US over who is to succeed current Republican President George W Bush," according to the German news agency Deutsche Presse Agentur.[252]

Prison ships

The United States has also been accused of operating "floating prisons" to house and transport those arrested in its war on terror, according to human rights lawyers. They have claimed that the US has tried to conceal the numbers and whereabouts of detainees. Although no credible information to support these assertions has ever come to light, the alleged justification for prison ships is primarily to remove the ability for jihadists to target a fixed location to facilitate the escape of high value targets, commanders, operations chiefs etc.[253]

Guantanamo Bay detention camp

The U.S. government set up the Guantanamo Bay detention camp in 2002, a United States military prison located in Guantanamo Bay Naval Base.[254] President Bush declared that the Geneva Convention, which protects prisoners of war, would not apply to Taliban and al-Qaeda detainees captured in Afghanistan.[255] Since inmates were detained indefinitely without trial and several detainees have allegedly been tortured, this camp is considered to be a major breach of human rights by Amnesty International.[256] The detention camp was set up by the U.S. government on Guantanamo Bay since the military base is not legally domestic US territory and thus was a "legal black hole."[257][258] Most prisoners of Guantanamo were eventually freed without ever being charged with any crime, and were transferred to other countries.[259] As of July 2021, 40 men remain in the prison and almost three-quarters of them have never been criminally charged. They're known as "forever prisoners" and are being detained indefinitely.[260]

Major terrorist attacks and plots since 9/11

Following the launch of "war on terror" by the United States, several Islamist militant groups as well as militant individuals have launched attacks against the assets of US-led coalition, including in Western countries where active warfare is not taking place.

Attacks by Al-Qaeda

- The 2002 Bali bombings in Indonesia were committed by various members of Jemaah Islamiyah, an organization linked to Al-Qaeda.

- Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb claimed responsibility for the 11 April 2007 Algiers bombings, which targeted the office of Algerian Prime Minister and a police station.

- Morocco blamed Al-Qaeda for the 2011 Marrakech bombing which targeted French nationals. However, al-Qaeda denies involvement in the attack.

- To date, no one has claimed responsibility for the 2012 U.S. Consulate attack in Benghazi in Libya, and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, pro-al-Qaeda militias and individuals "sympathetic to al-Qaeda" are considered to be the orchestrators of the attack. The attacks were launched 18 hours after al-Qaeda Emir Ayman al-Zawahiri released a video urging Muslims to attack on American targets in Libya to avenge the killing of al-Qaeda leader Abu Yahya al-Libi. The release of the video as well as the launching of the attacks coincided with the 11th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks.

- The gunmen in the Charlie Hebdo shooting in Paris identified themselves as belonging to al-Qaeda's Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

- Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula claimed responsibility for the Naval Air Station Pensacola shooting in the United States.

Islamic State

- 2013 Reyhanlı bombings in Turkey that led to 52 deaths and the injury of 140 people.

- 2014 Canadian parliament shootings, an ISIL-inspired attack on Canada's Parliament, resulting in the death of a Canadian soldier and that of the perpetrator.

- 2015 Porte de Vincennes siege perpetrated by Amedy Coulibaly in Paris, which led to four deaths and the injury of nine others.

- 2015 Corinthia Hotel attack on 27 January in Libya that resulted in 10 deaths.

- 2015 Sana'a mosque bombings on 20 March that led to the death of 142 and injury of 351 people.[261]

- 2015 Curtis Culwell Center attack on 3 May 2015 that resulted in the injury of one security officer.

- November 2015 Paris attacks on the 13th that left at least 137 dead and injured at least 352 civilians caused France to be put under a state of emergency, close its borders and deploy three French contingency plans.[262] Islamic State claimed responsibility for the attacks,[263] with French President François Hollande later stated the attacks were carried out "by the Islamic state with internal help".[264]

- 2015 San Bernardino attack on 2 December 2015, two gunmen attacked a county building in San Bernardino, California killing 16 people and injuring 24 others.[265]

- 2016 Brussels bombings on 22 March 2016 two bombing attacks, first at Brussels Airport and the second at the Maalbeek/Maelbeek metro station, killed 35 people and injured more than 300.[266]

- 2016 Orlando nightclub shooting on 12 June 2016 a gunman opened fire at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida killing 50 people and wounding 53 others. It was the second worst mass shooting in U.S. history.[267]

- 2024 Crocus City Hall attack, ISIS–K gunmen launched an attack on a concert hall in Krasnogorsk, Russia, killing 145 people and wounding 551 others. It was the deadliest terrorist attack on Russian soil since the Beslan school siege in 2004.

Attacks by other Islamist militant groups and individuals

- The 2003 Casablanca bombings were carried out by Salafia Jihadia militant group.

- After the 2003 Istanbul bombings which attacked British and Jewish targets, Turkey charged 74 people with involvement, including Syrian al-Qaeda member Loai al-Saqa. Islamist group Great Eastern Islamic Raiders' Front claimed responsibility for the attacks

- The 2004 Madrid train bombings in Spain were carried out by Moroccan-born Jamal Zougam and five other individuals in opposition to Spanish participation in the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq.

- The 7 July 2005 London bombings in the United Kingdom, which targeting London's public transport system, were perpetrated by four Islamist militants.

- The 2009 Fort Hood shooting in the United States was committed by Nidal Hasan, who had been in communication with Anwar al-Awlaki. The U.S. Department of Defense classified the shooting as an incidence of workplace violence.

- The 2007 Glasgow International Airport attack in the United Kingdom was carried out by Bilal Abdullah and Kafeel Ahmed.

- The 2012 Toulouse and Montauban shootings which targeted French soldiers and a Jewish school, were committed by Mohammed Merah. Although Merah claimed ties to al-Qaeda, French authorities have denied any connection.

- The 2023 7th October Attack which targeted Israeli soldiers and civilians, were committed by Hamas and its allies. With a barrage of at least 3,000 rockets launched against Israel and vehicle-transported and powered paraglider and infantry incursions into Israel, it was the deadliest terrorist attack in Israel's history and the third-deadliest terrorist attack in the 21st century.[268]

Alleged plots and unsuccessful attacks

There have also been reports of alleged plots and other planned attacks that were not successful.

- 2001 threat against West Coast suspension bridges (United States), though this was not corroborated

- 2004 financial buildings plot (The United States and the United Kingdom)

- 21 July 2005 London bombings (United Kingdom)

- 2006 Toronto terrorism plot (Canada)

- 2006 transatlantic aircraft plot involving liquid explosives carried onto commercial airplanes

- 2006 Hudson River bomb plot (United States)

- 2007 Fort Dix attack plot (United States)

- 2007 London car bombs (United Kingdom)

- 2007 John F. Kennedy International Airport attack plot (United States)

- 2009 Bronx terrorism plot (United States)

- 2009 New York City Subway and United Kingdom plot (The United States and the United Kingdom)

- 2009 Northwest Airlines Flight 253 bombing plot (United States)

- 2010 Stockholm bombings (Sweden)

- 2010 Times Square car bombing attempt (United States)

- 2010 cargo plane bomb plot (United States)

- 2010 Portland car bomb plot (United States)

- 2011 Manhattan terrorism plot (United States)

- 2013 Via Rail Canada terrorism plot (Canada)

- 2014 mass-beheading plot (Australia)

Casualties

There is no widely agreed on figure for the number of people that have been killed so far in the war on terror as the Bush Administration has defined it to include the war in Afghanistan, the war in Iraq, and operations elsewhere. According to Joshua Goldstein, an international relations professor at the American University, The global war on terror has seen fewer war deaths than any other decade in the past century.[269]

A 2015 report by the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War and the Physicians for Social Responsibility and Physicians for Global Survival estimated between 1.3 million to 2 million casualties from the war on terror.[270] A report from September 2021 by Brown University's Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs "Costs of War" project puts the total number of casualties of the war on terror in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan at between 518,000 and 549,000. This number increases to between 897,000 and 929,000 when the wars in Syria, Yemen, and other countries are included. The report estimated that many more may have died from indirect effects of war such as water loss and disease.[271][272][22] They also estimated that over 38 million people have been displaced by the post-9/11 wars participated in by the United States in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria, Yemen, Somalia, and the Philippines; 26.7 million people have returned home following displacement.[273][23] The conflict has caused the largest number of forced displacements by any single war since 1900, with the exception of World War II.[273]

In a 2023 report, the "Costs of War" project estimated that, as the result of the destruction of infrastructure, economies, public services and the environment, there have been between 3.6 and 3.7 million indirect deaths in the post-9/11 war zones, with the total death toll being 4.5 to 4.6 million and rising.[274] The report defined post-9/11 war zones as conflicts that included significant United States counter-terrorism operations since 9/11, which in addition to the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan, also includes the civil wars in Syria, Yemen, Libya and Somalia. The report derived its estimate of indirect deaths using a calculation from the Geneva Declaration of Secretariat which estimates that for every person directly killed by war, four more die from the indirect consequences of war. The report's author Stephanie Savell stated that in an ideal scenario, the preferable way of quantifying the total death toll would have been by studying excess mortality, or by using on-the-ground researchers in the affected countries.[2]

An estimated 7,052 US military combatants, over 8,100 US military contractors and more than 14,800 US-allied coalition troops are estimated to have been killed in the wars as of 2023.[275]

The total number of insurgent deaths since the commencement of the war on terror in 2001 is generally estimated as being well into the hundreds of thousands, with hundreds of thousands of others captured or arrested. Some estimates for regional conflicts include the following:

Iraq

In Iraq, some 26,544 insurgents were killed by the American-led coalition and the Iraqi Security Forces from 2003 to 2011.[276] 119,752 suspected insurgents were arrested in Iraq from 2003 to 2007 alone, at which point 18,832 suspected insurgents had been reported killed;[277] applying this same arrested-to-captured ratio to the total number of insurgents killed would equate to approximately 26,500 insurgents killed and 168,000 arrested from 2003 to 2011. At least 4,000 foreign fighters (generally estimated at 10–20% of the insurgency at that point) had been killed by September 2006, according to an official statement from al-Qaeda in Iraq.[278] Insurgent casualties in the 2011–2013 phase of the Iraqi conflict numbered 916 killed, with 3,504 more arrested.

From 2014 to the end of 2017, the United States government stated that over 80,000 Islamic State insurgents had been killed by American and allied airstrikes from 2014 to the end of 2017, in both Iraq and Syria. The majority of these strikes occurred within Iraq.[279] ISIL deaths caused by the Iraqi Security Forces in this time are uncertain, but were probably significant. Over 26,000 ISF members were killed fighting ISIL from 2013 to the end of 2017,[280] with ISIL losses likely being of a similar scale.

Total casualties in Iraq range from 62,570 to 1,124,000:

- Iraq Body Count project documented 185,044 to 207,979 dead from 2003 to 2020 with 288,000 violent deaths including combatants in total.

- 110,600 deaths in total according to the Associated Press from March 2003 to April 2009.[281]

- 151,000 deaths in total according to the Iraq Family Health Survey.[282]

- Opinion Research Business (ORB) poll conducted 12–19 August 2007 estimated 1,033,000 violent deaths due to the Iraq War. The range given was 946,000 to 1,120,000 deaths. A nationally representative sample of approximately 2,000 Iraqi adults answered whether any members of their household (living under their roof) were killed due to the Iraq War. 22% of the respondents had lost one or more household members. ORB reported that "48% died from a gunshot wound, 20% from the impact of a car bomb, 9% from aerial bombardment, 6% as a result of an accident and 6% from another blast/ordnance."[283][284][285]

- Between 392,979 and 942,636 estimated Iraqi (655,000 with a confidence interval of 95%), civilian and combatant, according to the second Lancet survey of mortality.

- A minimum of 62,570 civilian deaths reported in the mass media up to 28 April 2007 according to Iraq Body Count project.[286]

- 4,431 U.S. Department of Defense dead (941 non-hostile deaths), and 31,994 wounded in action during Operation Iraqi Freedom. 74 U.S. Military Dead (36 non-hostile deaths), and 298 wounded in action during Operation New Dawn as of 4 May 2020[287]

Afghanistan

Insurgent and terrorist deaths in Afghanistan are hard to estimate. Afghan Taliban losses are most likely of a similar scale to Afghan National Army and Police losses; that is around 62,000 from 2001 to the end of 2018.[288] In addition, al-Qaeda's main branch and ISIL's Afghanistan branch are each thought to have lost several thousand killed there since 2001.[289][290]

Total casualties in Afghanistan range from 10,960 and 249,000:[291]

- 16,725–19,013 civilians killed according to Cost of War project from 2001 to 2013[292]

- According to Marc W. Herold's extensive database,[293] between 3,100 and 3,600 civilians were directly killed by U.S. Operation Enduring Freedom bombing and Special Forces attacks between 7 October 2001 and 3 June 2003. This estimate counts only "impact deaths"—deaths that occurred in the immediate aftermath of an explosion or shooting—and does not count deaths that occurred later as a result of injuries sustained, or deaths that occurred as an indirect consequence of the U.S. airstrikes and invasion.