South Eastern Main Line

| South Eastern Main Line | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Southeastern electric multiple units at Charing Cross in 2009 | |||

| Overview | |||

| Status | Operational | ||

| Owner | Network Rail | ||

| Locale | |||

| Termini | |||

| Stations | 29 | ||

| Service | |||

| Type | Commuter rail, Regional Rail | ||

| System | National Rail | ||

| Operator(s) | SE Trains | ||

| Depot(s) | |||

| Rolling stock | |||

| History | |||

| Opened | 1842–44 in stages | ||

| Technical | |||

| Line length | 77mi 23ch (124.38 km) | ||

| Number of tracks |

| ||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge | ||

| Electrification | 750 V DC third rail | ||

| Operating speed | 100 mph (161 km/h) maximum | ||

| |||

South Eastern Main Line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The South Eastern Main Line is a major long-distance railway route in South East England, UK, one of the three main routes crossing the county of Kent, going via Sevenoaks, Tonbridge, Ashford and Folkestone to Dover. The other routes are the Chatham Main Line which runs along the north Kent coast to Ramsgate or Dover via Chatham and High Speed 1 which runs through the centre of Kent to the coast at Folkestone where it joins the Channel Tunnel.

History

[edit]Construction

[edit]

The line was built by the South Eastern Railway (SER), which was in competition with the London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LCDR), hence the duplication of routes in Kent.

The original main line was given sanction by Act of Parliament in 1836. The route first authorised was from London Bridge via Oxted, Tunbridge,[a] Maidstone, Ashford and Folkestone.[2] The route was to make use of the existing London and Croydon Railway and London and Greenwich Railway companies' tracks.[3] The SER did not have much spare capital. As a cost-cutting measure, authorisation was secured in 1837 to make the junction with the London and Croydon Railway at Norwood, Surrey.[b] instead of at Corbett's Lane.[4] However, the London and Brighton Railway was authorised to build from Norwood southwards in 1847. Parliament suggested that further savings could be made by avoiding having lines running in parallel valleys for 12 miles (19 km) if the SER were to make its junction further south. The London and Brighton were to construct the line, and the SER were to purchase it at cost on completion. Both companies would operate trains over the route. The London and Brighton took advantage of this to ensure that gradients would be kept as shallow as possible, even at the expense of substantial earthworks and a mile-long tunnel at Merstham. The SER main line diverged from the London and Brighton's line at Reigate Junction, which the London and Brighton opened to traffic on 12 July 1841.[2]

Leaving the Brighton line, the railway took a direct route to Folkestone; plans to serve Maidstone were abandoned.[5] A branch line was to be built from Maidstone Road instead.[6] The line was almost direct between Redhill and Ashford, not deviating by more than 0.5 miles (800 m) in either direction.[5] The engineer was Sir William Cubitt. To facilitate fast running, Tunbridge, Maidstone Road and Ashford stations were built with through roads.[6] Headcorn station was to be rebuilt on a similar plan in 1924.[7] Construction began in November 1837 from Reigate Junction eastwards, and in both directions from Tunbridge. The line from London Bridge to Tunbridge opened on 26 May 1842. The line between Tonbridge and Ashford opened on 1 December 1842.[8]

East Kent

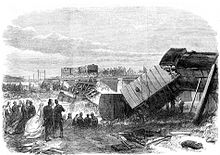

[edit]No major engineering works were needed until Folkestone was reached, where a 100 ft (30 m) high viaduct was needed to cross the Foord Gap.[9] A temporary station was provided at Folkestone, which opened on 28 June 1843. With the completion of the viaduct, Folkestone station opened on 18 December 1843.[8] East of Folkestone, a hard gault ridge was bored through by the Martello Tunnel, which took its name from a nearby Martello Tower.[9] Between Folkestone and Dover, there were three headlands, Abbott's Cliff, Round Down Cliff and Shakespeare's Cliff. The first and last were of sound chalk, but Round Down Cliff's chalk was of a different character, and was found to be unstable. Cubitt sought the advice of Lieutenant Hutchinson, Royal Engineers, who had experience in using dynamite in the clearing of the wreck of HMS Royal George in 1840.[10] It was decided to blow the cliff away over a distance of 500 ft (150 m).[11] On 18 January 1843, a total of 18,500 lb (8,400 kg) of gunpowder was used in three charges to blow away the cliff face. An estimated 1,000,000 tons of chalk was dislodged.[12] As the chalk in Shakespeare's Cliff was not as strong as that of Abbot's Cliff, two single line tunnels were bored.[13] East of Shakespeare Tunnel, a low trestle bridge was built across the beach to gain access to Dover.[14] The line between Folkestone and Dover opened on 7 February 1844.[8]

In 1843, permission was obtained to build the branch line from Paddock Wood to Maidstone. It opened on 25 September 1844.[15] In May 1844, permission was gained to build a railway from Ashford to the Isle of Thanet, serving both Margate and Ramsgate. The line opened as far as Canterbury on 6 February 1846.[16] In 1845, permission was obtained to build a branch line to Tunbridge Wells.[17] This line opened on 19 September 1845,[18] and was extended to Hastings, East Sussex in 1852.[19] Also in that year, permission was obtained to build a railway from Ashford to Hastings, which opened on 13 February 1851.[20] Tunbridge station was renamed Tunbridge Junction on 1 February 1852.[21]

Both Dover and Folkestone provided access to the English Channel, and thus to the French ports of Calais and Boulogne.[22] At Folkestone, the Pent Brook stream that ran through the Foord Gap had built up a spit of shingle, which acted as a breakwater and provided an anchorage.[23] The SER built a steeply-graded branch line to the harbour, with a reversal required to reach it. It opened to freight in 1843.[24] Passengers were transferred from Folkestone station to the harbour by bus, with mail and freight going by rail. A swing bridge was constructed in 1847, and Folkestone Harbour station opened in 1850. Ships could berth at any state of the tide.[25] The SER started a cross-channel steamship service to Boulogne. At Dover, the River Dour had formed a shingle spit and thus a small harbour which required constant dredging to keep open. Cross-Channel traffic was operated by Admiralty ships to Calais.[citation needed] Neither French port was connected by railway at the time. The SER partly financed the construction of the Boulogne & Amiens Railway, which opened in 1848. Calais was reached by rail in that year.[26] Larger and larger ships were built for the cross-Channel service; these could use Folkestone Harbour only at high tide in the 1860s whilst the pier was extended. Trains connecting with cross-Channel ships thus ran according to the state of the tide, not to a fixed timetable. This was a factor in a serious accident at Staplehurst on 9 June 1865.[26][27]

The development of Dover Harbour was largely out of SER's hands. The harbour itself was under the control of the Harbour Commissioners, who were deputies of the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. Other land that might be developed was in the hands of the Admiralty. Dover Corporation had no influence over either body. They were forced to watch the development of Folkestone as a port whilst little was done to improve things in what was the premier of the Cinque Ports. As far back as the reign of Elizabeth I, there had been plans to build a breakwater at Dover. In 1836, a parliamentary inquiry was set up, and eventually construction of a breakwater was begun in 1847. The Admiralty Pier was to be wide enough for two railway lines to be accommodated.[28] In use by 1864, the pier was completed in 1871.[29] Another problem was a lack of decent hotel accommodation in Dover. The Harbour Commissioners had sold the SER a parcel of land on which the station was built. The SER wanted to build the hotel at a position where it would serve both cross-channel and local traffic. They approached the Harbour Commissioners for permission to buy the desired site, but were refused on the grounds that they had not built on land they had previously purchased. Thus the Lord Warden Hotel was built, opening in 1851.[30] Through the 1850s, Folkestone saw more traffic than Dover, although the latter port was growing at a faster rate.[31][26]

Further connections

[edit]In 1857, a new direct connection was put in at Tunbridge Junction, enabling trains to reach Hastings without reversing. The station at Tonbridge was rebuilt on a new site just west of the original.[21] The LCDR built their line to Dover, which opened in 1861,[32] providing a route to London that was 16 miles (26 km) shorter that the SER line via Redhill.[33] In May 1862, authorisation was obtained to construct a new railway from St Johns, London to Tonbridge, which reduced the distance from London to Tonbridge and points east by about 13 miles (21 km). Construction of the tunnels was well supervised by the SER, for it had been discovered by then that the contractors who had built the tunnels on the Hastings line had skimped on the construction by using an insufficient number of rings of bricks to line the tunnels. Rectification resulted in a restricted loading gauge on that line,[34] a situation that was to last until 1986.[35] This "cut-off" line, 24 miles (39 km) in length, reached Chislehurst & Bickley Park on 1 July 1865. This station was replaced with a new one 600 yards (550 m) further south, which opened on 2 March 1868 when the line was extended to Orpington and Sevenoaks.[36][37] The line between Sevenoaks and Tonbridge opened to freight in February 1868, and to passengers on 1 May 1868.[21] Sevenoaks Tunnel took five years to build, from 1863 to 1868, It is 3,493 yards (3,194 m) long. On opening, it was the fifth longest railway tunnel in the United Kingdom.[38] This new line meant that the old main line from Redhill was relegated to branch line status.[21]

In 1872, construction began on a branch line from Sandling to Sandgate, near Folkestone. Proposals to extend this, or to build a line from Shorncliffe which would have passed under the Foord Gap Viaduct, to Folkestone Harbour, were defeated by local opposition.[39] Much of the land required was owned by the Earl of Radnor, who was opposed to the schemes.[40] In 1881, powers were obtained to build the Elham Valley Railway. It opened between Canterbury and Shorncliffe in 1889, stopping the LCDR from building its rival scheme, to which there was much opposition amongst the residents of Folkestone.[41] The line opened in 1889.[42] On the main line, two stations were built west of Folkestone: Cheriton Arch and Shorncliffe Camp, which replaced the earlier Shorncliffe & Sandgate station. Cheriton Arch opened on 1 September 1884.[43][44][45] The new Shorncliffe Camp opened a month later, on 1 October.[45]

The LCDR reached Ashford in 1884 from Swanley Junction via Maidstone.[46] They built their own station, Ashford West. It was not until 1 November 1891 that a connection was made between the two lines.[47] On 1 October 1892, the Cranbrook and Paddock Wood Railway opened their branch from Paddock Wood to Hope Mill, for Goudhurst and Lamberhurst. It was extended to Hawkhurst on 4 September 1893.[48] In 1905, the Kent and East Sussex Railway extended their line from Tenterden Town to Headcorn. A junction was built just east of the station.[49] In 1910, work began on the construction of Dover Marine station, groundwork for which was to take three years to complete.[50] The station opened on 2 January 1915 for ambulance trains.[51]

Operation

[edit]From the outset, the line was worked by steam locomotives. Early locomotive classes that worked the line include the "Little Mail", and "Mail" class 2-2-2s.[52] By the 1860s the speed limit on the line was 60 miles per hour (97 km/h). In those days, shingle was used for ballast. This was fine for the speeds and train weights then in use, but became less satisfactory as train speeds and weights increased. The use of shingle ballast was a factor in a serious accident at Sevenoaks in 1927.[53] In the 1870s, James Stirling introduced a number of new classes: the B and F class 4-4-0s for express passenger work; the O class 0-6-0s for freight; and the A class 4-4-0s and Q class 0-4-4Ts for local passenger work. The R class 0-6-0Ts were built to perform banking duties on the branch from Folkestone Harbour to Folkestone Junction. Classes F, O and Q accounted for the majority of the 459 locomotives in the six classes.[54] The SER and LCDR agreed in 1898 to form a working arrangement.[55] The South Eastern and Chatham Railway (SECR) came into being on 1 January 1899.[47] The new company was short of locomotives and was glad to acquire five 4-4-0s that the Great North of Scotland Railway had ordered from Hurst, Nelson & Co Ltd, Glasgow but which subsequently had become surplus to their requirements. These locomotives became the G class.[56] In 1900, Harry Wainwright introduced the C class 0-6-0s for freight, and D and E class 4-4-0s for express passenger work. The latter two classes were capable of 75 miles per hour (121 km/h).[57] The track having been upgraded to enable running at such speed.[50] Richard Maunsell introduced the River class 2-6-4Ts in 1917 for express passenger trains.[58] Post-war, the D and E classes were rebuilt with superheaters. The rebuilt locomotives were designated as classes D1 and E1.[59]

With the introduction of electric trains in the late 1920s, a large number of three-car electric multiple units and two-car trailer sets were built. Some were built new by the Metropolitan Carriage, Wagon and Finance Company with trailers by the Birmingham Railway Carriage and Wagon Company, but the majority were converted from ex-SECR, LBSC or LSWR carriages. The former LBSC 6.7kV AC electric multiple units were also converted.[60] After World War II, many of the three-coach units were reformed as four-car units by the addition of an ex-LSWR 10-compartment carriage. Some units gained a brand new carriage. Other units were formed from various carriages that were part of units that had been damaged by accidents or enemy action. From 1946 to 1950, a number of units were built at Eastleigh Works.[61] The units collectively were designated 4SUB.

Electrification

[edit]In 1903, the SECR obtained powers to electrify their lines. At a meeting in 1913, SECR chairman H. Cosmo Bonsor said that the time was not right for the company to incur the heavy expenditure of electrification. The outbreak of war meant the postponement of any plans to electrify suburban lines. With the passing of the Trades Facilities Act 1922, the SECR proposed to electrify a number of lines in three stages. The SEML was to be partly electrified as follows: Charing Cross and Cannon Street to Orpington as part of Stage 1; Orpington to Tonbridge as part of Stage 2, which also included the electrification of the former SEML between Redhill and Tonbridge. Both stages only covered the working of local passenger trains on the lines that were electrified. Stage 3 was to extend the working to through passenger trains and freight. Permission was sought in 1922 to build an electricity generating station at Charlton, London. This was refused by the Electricity Commissioners, who insisted that the company bought electricity from an existing supply company. Objections to this by the SECR were not entertained.

On 1 January 1923, the SECR became part of the Southern Railway (SR).[62]

The SR decided that the electrification system was to be 660 V DC third rail.[63] The first station on the SEML to see electric trains was Orpington, which was the terminus for electric trains from Victoria via Herne Hill and Shortlands. Public services commenced on 12 July 1925.[64] In preparation for Stage 2 of the electrification, the lines between Charing Cross and Metropolitan Junction were remodelled. Semaphore signals were replaced by colour light signals, with a new temporary manual signal box provided at Charing Cross. The lines serving Cannon Street were electrified. Electric trains were due to start on 1 December 1925, but power supply problems meant that the introduction of electric trains from Charing Cross and Cannon Street to Orpington was postponed until 28 February 1926.[65] Cannon Street was closed from 5–28 June 1926 for alterations to the track layout and platforms. On 27 June, new four aspect colour light signals were brought into use between Cannon Street, Charing Cross and Borough Market Junction. New power signal boxes came into service at the two termini, but Metropolitan Junction remained a manually-worked box, although it was provided with a new 60-lever frame.[66] With the introduction of the new service on 28 June, a new station was opened at Petts Wood.[67] On 30 June 1929, four-aspect colour light signals were introduced between New Cross and Hither Green. New power signal boxes were provided at St Johns and Parks Bridge Jn, enabling seven manual boxes to be abolished.[62] On 1 December 1929, four-aspect colour light signals were introduced between Spa Road and New Cross. A new power box at North Kent East Junction allowed the abolition of seven more manual boxes.[68] The increased services provided by electric trains meant that there were fewer paths available for freight trains to reach the marshalling yard at Hither Green. Therefore, the Greenwich Park Branch Line, which had closed on 1 January 1917 and thereafter was only used by freight trains as far as Brockley Lane, was brought back into use on 30 June 1929 as far as the point at which it crossed the SEML, a new spur being provided to give access to Hither Green. The reopened section of line was also electrified and provided with four aspect colour light signalling.[67]

In 1934, it was announced that the electrification of the SEML would be extended to Sevenoaks, including the loops at Chislehurst Jn. Electric services from Sevenoaks began on 6 January 1935.[69] In February 1936, it was announced that the SR intended to extend electrification of the SEML to Tonbridge, as part of a scheme to electrify the Hastings line. In February 1937, it was announced that this part of a wider electrification scheme would be completed in January 1939. However, in February 1938, it was announced that the Hastings electrification had been abandoned due to the cost of having to either build dedicated rolling stock or rebore the tunnels to allow ordinary stock to work through them.[70]

In 1954, Charing Cross, and to a lesser extent London Bridge, were remodelled to enable them to handle 10-coach trains on the suburban network.[71] Cannon Street station was remodelled in 1955. On 5 April 1957, a fire destroyed the signal box at Cannon Street and severely affected the operation of trains. Following the construction of a temporary signal box, a reduced service was operated from 5 May, a skeleton service having operated in the interim.[72] A new signal box was built, coming into service on 16 December.[73]

British Railways started to implement its 1955 Modernisation Plan. This extended electrification to the Kent Coast in two stages, with the South Eastern Main Line being subject of "Kent Coast Electrification - Stage 2".[74] As part of Stage 1, Chislehurst Jn was rebuilt to allow an increase of speed on the connecting lines from 30 miles per hour (48 km/h) to 50 miles per hour (80 km/h).[75] Stage 2 extended electrification along the remainder of the SEML to Dover. Ashford, Shorncliffe and Folkestone Central stations were rebuilt.[74] Colour light signalling was installed throughout, with new signal boxes being built at Hither Green, Chislehurst Junction, Orpington, Sevenoaks, Tonbridge, Ashford and Folkestone Junction. This allowed the abolition of 32 signal boxes, with eleven more reduced to occasional use and one being manned during morning peak hours only.[76] Electric services on the full length of the SEML began on 12 June 1961.[77] This was accompanied by a voltage upgrade to 750 V DC across the whole the Southern Region.[citation needed] Completion of the scheme would allow the phasing out of steam from the Eastern area of the Southern Region of British Railways.[78] Folkestone East closed to passengers on 6 September 1965.[79] In December 1969, it was announced that all electric multiple units built before 1939 were to be withdrawn by 1972.[80] In 1972, work began on rebuilding and resignalling London Bridge, with a new power signal box built at London Bridge. The scheme cost £23.5 million and was completed in December 1978.[81]

The line was largely left untouched, until the arrival of the Channel Tunnel at Cheriton, near Folkestone. Prior to construction of High Speed 1, also known as the Channel Tunnel Rail Link (CTRL), services ran over the South Eastern Main Line to Petts Wood, leaving at Chislehurst junction onto the Chatham Main Line. Freight services for the Channel Tunnel were routed via the Maidstone East Line. The CTRL was built alongside the line to Ashford where is joined in to gain access to the existing station. The CTRL diverges west of Ashford to pursue a separate route to its new London terminus (St Pancras). Thus a short section of the line through Ashford is also electrified at 25 kV AC.

Accidents

[edit]Over the years, a number of accidents have occurred at various locations on the South Eastern Main Line.

- On 28 July 1845, a passenger train was run into by a steam locomotive at Penshurst, injuring about 30 people.[82]

- On 21 January 1846, a bridge over the River Medway collapsed in a flood. The driver of a freight train was killed when he tried to jump clear of the train.[83]

- 9 June 1865 - the Staplehurst rail crash. An error by track workers resulted in the deaths of ten people when a train crossed a bridge from which the rails had been removed. A further 40 people were injured, including Charles Dickens.

- On 30 September 1866, the slip portion of a train, which was to be worked forwards to Hastings, failed to stop at Tunbridge due to an error by the slip guard. It crashed into a rake of empty carriages 262 yards (240 m) east of the station. Eleven of the 40 passengers were injured.[84]

- January 1877 - a landslip at the eastern end of Martello Tunnel brought down some 60,000 cubic yards (46,000 m3) of chalk, killing three men. The line was closed for two months.[85]

- 7 June 1884 - A double-headed freight train ran into the rear of another freight train at Tub's Hill station, Sevenoaks. Both crew of the first train were killed. the Hildenborough signalman was charged with causing their deaths. The trains were being worked under the time interval system.[86]

- 5 December 1905 - the Charing Cross roof collapse. Structural failure of the overall roof at Charing Cross station led to the death of six people.

- 5 March 1909 - A train for Redhill overran signals and collided with a boat train at Tonbridge. Two people were killed and eleven were injured.[87]

- 19 December 1915 - a landslip between Martello Tunnel and Abbotscliff Tunnel derailed a passenger train hauled by a D class locomotive. Nearly 2 miles (3.22 km) of line was affected. At Folkestone Warren Halt the line had been pushed 53 yards (48 m) towards the sea.[88]

- 5 May 1919 - a goods train overran signals and ran into the back of another goods train at Paddock Wood. One person was killed.[89]

- 24 August 1927 - the Sevenoaks railway accident. River class tank locomotive No. 800 River Cray derailed on passing under the Shoreham Lane bridge between Dunton Green and Sevenoaks.[90] Thirteen people were killed and 20 were injured. The locomotives were withdrawn and rebuilt as tender locomotives.

- 4 December 1957 - the Lewisham rail crash. A train hauled by Battle of Britain class steam locomotive 34066 Spitfire ran into the rear of a train comprising two four-coach electric multiple units and one two-coach electric multiple unit, having passed a signal at danger. The accident happened under a bridge carrying the Greenwich Park branch line. The bridge collapsed onto the wreckage of the two trains, killing 90 people and injuring 173.

- 12 August 1958 - the 06:52 Sanderstead to Cannon Street train derailed at Borough Market Junction, completely blocking all lines into Charing Cross. The cause was worn trackwork at Borough Market Junction.[91]

- 28 January 1960 - the 13:22 Hayes to Charing Cross overran signals at Borough Market Junction and was in a sidelong collision with the 12:20 Hastings to Charing Cross. The 14:53 Charing Cross to Tattenham Corner then ran into the derailed Hayes train. Seven people were injured.[92]

- 8 December 1961 - at 02:02, a goods train was setting back at Paddock Wood when the 00:20 goods from Hoo Junction to Tonbridge overran signals and collided with it. The wreckage from the accident piled up under the bridge carrying the B2160 Maidstone Road. The line was blocked for 12 hours.[93]

- 5 November 1967 - the Hither Green rail crash. A train formed of two 6S diesel-electric multiple units derailed on a broken rail at Hither Green, killing 49 people and injuring 78.

- 4 January 1969 - the Marden rail crash. A train formed of two 4CEP electric multiple units ran into the back of a parcels train just west of Marden after passing a signal at danger. Four people were killed and eleven were injured.

- 17 February 1970 - an electric multiple unit was derailed at Borough Market Junction, causing suspension of services between Waterloo East and Charing Cross.[94]

- 6 May 1975 - an electric multiple unit was derailed at Borough Market Junction. No trains were able to run directly between Charing Cross and Waterloo East until the next day.[95]

- 4 March 1976 - a bomb exploded on an empty stock train at Cannon Street. Eight people in an adjacent train were injured.[96]

- 14 September 1996 - a wagon in a freight train hauled by 47 360 and 47 033 derailed near Staplehurst due to the train being driven at a speed in excess of the wagon's speed limit and the wagon probably being loaded unevenly.[97]

- 8 January 1999 - the Spa Road Junction rail crash. An eight-coach train comprising a 4CEP and a 4VEP electric multiple unit collided with an eight-coach train comprising two Class 319 electric multiple units after the former train passed a signal at danger. Four people were injured.

- 24 December 2015 - damage to the sea wall between Dover Priory and Folkestone Central led to closure of the line "until further notice",[98] later reported to be until the end of February.[99] In mid-February 2016, it was revealed that the original wooden viaduct which carried the line, and had been subsequently infilled, had rotted. The section of line affected would need to be completely rebuilt, a process which would take much longer than originally envisaged.[100] Network Rail Chief Executive Mark Carne stated that repairs could take "six to twelve months",[101] although works were completed ahead of schedule with the line reopening on 5 September.

Services

[edit]

Stopping services run from Charing Cross or Cannon Street to Orpington or Sevenoaks, with other services on the route running fast over this section. Beyond Sevenoaks, stopping services originating from Tunbridge Wells, just off the main line, cover the stations with other services on the route running fast over this section

At Tonbridge services from the original main route – now the rural Redhill–Tonbridge line – join from Redhill, while the main line to Hastings via Tunbridge Wells diverges.

At Paddock Wood the Medway Valley line diverges.

At Ashford the Maidstone East Line (from Swanley) and High Speed 1 joins, while several lines diverge: the Canterbury West line (to Ramsgate and beyond), High Speed 1 and Marshlink (to Hastings).

As of December 2022 there are four off-peak "Kent Coast" services between London and Tonbridge:

- 1 train per hour (tph) from Charing Cross to Ashford International and Dover Priory

- 1 tph from Charing Cross to Ashford International, Canterbury West and Ramsgate

- 1 tph from Charing Cross to Hastings, all stops from Tunbridge Wells

- 1 tph from Charing Cross to Hastings, semifast

From Ashford International to Dover Priory there is a further 1tph formed by a HS1 service from St Pancras.

There are a further four "Metro" services on the suburban part of the line:

- 2 tph from Charing Cross to Orpington and Sevenoaks

- 2 tph from Cannon Street to Orpington

- Additional Metro services diverge off the line at Lewisham or Hither Green.

Rolling stock

[edit]Services are formed using SE Trains’s fleet of Class 375 and Class 376 Electrostars and older Class 465 and Class 466 Networker units. Previously Class 377 or Class 455s operated by Southern ran on the line between the London terminus and London Bridge.

Sights

[edit]

The major rail depots, visible near Hither Green, are the Hither Green Traction Maintenance Depot (TMD) and the nearby Grove Park Depot and Sidings.

Picturesque and unfamiliar sights (to visitors) on the line are oast houses, traditional farm buildings used for drying hops, whose conical roofs are tipped by distinctive cowls.

Notes

[edit]- ^ The modern spelling of "Tonbridge" was not adopted as the official spelling until 1870.[1]

- ^ As it was until 21 March 1889, following the passing of the Local Government Act 1888.

References

[edit]- ^ Chapman 1995, p. 6.

- ^ a b Nock 1961, p. 12.

- ^ Nock 1961, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Nock 1961, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Nock 1961, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b Nock 1961, p. 14.

- ^ Mitchell & Smith 1985, Illustration 114.

- ^ a b c "Tonbridge". Kentrail. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ a b Nock 1961, p. 15.

- ^ Nock 1961, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 16.

- ^ "Great Blast at the Dover Railway". Illustrated London News. No. 39. 28 January 1843. p. 55.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 127.

- ^ Nock 1961, pp. 17, facing p.32.

- ^ "Maidstone West". Kentrail. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ "Wye". Kentrail. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ "Domestic News". The Standard. No. 3799. London. 2 August 1845. p. 5.

- ^ Jewell 1984, p. 91.

- ^ Beecroft 1986, p. 8.

- ^ "Ham Street & Orlestone". Kentrail. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Tonbridge". Kentrail. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ Nock 1961, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Nock 1961, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 18.

- ^ Nock 1961, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b c Nock 1961, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Rich 1865, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Nock 1961, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 93.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 42.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 43.

- ^ Dendy Marshall 1968, p. 326.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 45.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 65.

- ^ Beecroft 1986, p. 74.

- ^ "Chislehurst". Kentrail. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ "Orpington". Kentrail. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ Leeds, Tessa (2000). "The construction of the Sevenoaks railway tunnel" (PDF). Archaeologia Cantiana. 120. Kent Archaeology Society: 187–204.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 39.

- ^ Nock 1961, pp. 81–84.

- ^ Nock 1961, pp. 84, 89.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 89.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 90.

- ^ "Folkestone Central". Kentrail. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Folkestone East". Kentrail. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ Mitchell & Smith 1994, Historical Background.

- ^ a b Mitchell & Smith 1994, Ashford West.

- ^ Harding 1998, p. 5.

- ^ Mitchell & Smith 1985, Headcorn.

- ^ a b Nock 1961, p. 144.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 156.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. between pp. 32-33.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 92.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 96.

- ^ Nock 1961, pp. 124–25.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 128.

- ^ Nock 1961, pp. 129, 132.

- ^ Nock 1961, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 172.

- ^ Moody 1979, pp. 77–83.

- ^ Moody 1979, pp. 110–12.

- ^ a b Moody 1979, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Moody 1979, p. 23.

- ^ Moody 1979, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Moody 1979, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Moody 1979, pp. 31–32.

- ^ a b Moody 1979, p. 42.

- ^ Moody 1979, p. 41.

- ^ Moody 1979, p. 50.

- ^ Moody 1979, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Moody 1979, p. 124.

- ^ Moody 1979, p. 128.

- ^ Glover 2001, pp. 138–39.

- ^ a b Moody 1979, p. 140.

- ^ Moody 1979, p. 135.

- ^ Moody 1979, pp. 141–42.

- ^ Moody 1979, p. 142.

- ^ Moody 1979, p. 126.

- ^ Moody 1979, p. 166.

- ^ Moody 1979, p. 207.

- ^ Moody 1979, pp. 223–25.

- ^ "Accident on the Dover Railway". The Times. No. 18988. London. 29 July 1845. col A, p. 5.

- ^ "Fearful and Fatal Accident on the South Eastern Railway". The Times. No. 19139. London. 21 January 1846. col D, p. 5.

- ^ Board of Trade (10 October 1866). "South Eastern Railway" (PDF). Railways Archive. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Nock 1961, p. 85.

- ^ Jewell 1984, p. not cited.

- ^ Chapman, Frank (6 March 2009). "Rail crash publicity huge as quick thinking saves King and Queen". Kent and Sussex Courier. Courier Group Newspapers.

- ^ Nock 1961, pp. 154–55.

- ^ Earnshaw 1993, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Fryer, Charles E.J. (1992). Railway Monographs No.1: The Rolling Rivers. Sheffield: Platform 5 Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 1-872524-39-7.

- ^ Glover 2001, pp. 139–40.

- ^ Moody 1979, p. 147.

- ^ "Rail Crash: Inquiry begins". Tonbridge Free Press. 15 December 1961. pp. 1, 10.

- ^ Moody 1979, pp. 208–09.

- ^ Moody 1979, p. 240.

- ^ Moody 1979, p. 231.

- ^ "Staplehurst 14/09/1996". Rail Safety & Standards Board. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Folkestone coastal train halted by sea wall cracks". BBC News. 27 December 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ "UPDATE: Folkestone to Dover railway line closed until END of FEBRUARY". Folkestone Herald. Local World. 27 December 2015. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ "MP Charlie Elphicke says sea wall between Dover and Folkestone will need full rebuild". Folkestone Herald. KM Group. 15 February 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ "Dover rail line collapse: Repairs to take 'up to a year'". BBC News. 16 February 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Beecroft, Geoffrey (1986). The Hastings Diesels Story. Chessington: Southern Electric Group. ISBN 0-906988-20-9. OCLC 17226439.

- Chapman, Frank (1995). Tales of Old Tonbridge. Brasted Chart: Froglets Publications Ltd. ISBN 1-872337-55-4. OCLC 41348297.

- Earnshaw, Alan (1993). Trains in Trouble, Volume Eight. Penryn: Atlantic. ISBN 0-906899-52-4.

- Glover, John (2001). Southern Electric. Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-2807-9.

- Harding, Peter A. (1982). The Hawkhurst Branch Line. Woking: Peter A. Harding. ISBN 0-9523458-3-8.

- Harding, Peter A. (1998) [1982]. The Hawkhurst Branch Line. Woking: Peter A. Harding. ISBN 0-9523458-3-8. OCLC 42005158.

- Jewell, Brian (1984). Down the line to Hastings. Southborough: The Baton Press. ISBN 0-85936-223-X.

- Dendy Marshall, C. F. (1968). R.W. Kidner (ed.). History of the Southern Railway. Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0059-X.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (1985). Branch Line to Tenterden. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 0-906520-21-5.

- Moody, G. T. (1979) [1957]. Southern Electric 1909-1979 (Fifth ed.). Shepperton: Ian Allan Ltd. ISBN 0-7110-0924-4.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (1994). Swanley to Ashford. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 1-873793-45-6.

- Nock, O.S. (1961). The South Eastern and Chatham Railway. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0268-1.

- Rich, F. H. (1865). Accident Report (PDF). Railway Department, Board of Trade. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

External links

[edit]- Rail transport in Kent

- Transport in the Borough of Ashford

- Transport in the London Borough of Bromley

- Transport in the City of London

- Transport in the London Borough of Lambeth

- Transport in the London Borough of Lewisham

- Transport in the London Borough of Southwark

- Transport in the City of Westminster

- Railway lines in London

- Railway lines opened in 1844

- Railway lines in South East England

- Electric railways in the United Kingdom

- Standard gauge railways in England