Locus Biosciences

| |

| Company type | Privately held company |

|---|---|

| Industry | Pharmaceutical company |

| Founded | May 22, 2015 in Raleigh, NC, USA |

| Founders | |

| Headquarters | Morrisville, North Carolina , United States |

| Brands | crPhage |

Number of employees | 80[4] (2021) |

| Website | www |

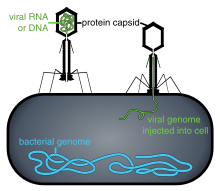

Locus Biosciences is a clinical-stage pharmaceutical company, founded in 2015 and based in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina.[2] Locus develops phage therapies based on CRISPR–Cas3 gene editing technology, as opposed to the more commonly used CRISPR-Cas9, delivered by engineered bacteriophages.[5] The intended therapeutic targets are antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections.[1][5]

History

[edit]The company was founded as a spin-off from North Carolina State University (NCSU) in 2015 with licensed CRISPR patents from the university.[6][7] The company started with a $5 million convertible note from Tencent Holdings and North Carolina Biotechnology Center.[8]

In 2017, the company closed a $19 million Series A led by Artis Ventures, Tencent Holdings Ltd, and Abstract Ventures.[7][8] In 2020, the company sold convertible notes in a debt raise to roll into its next equity round in 2021.[9]

In 2018, Locus acquired a high-throughput bacteriophage discovery platform from San Francisco-based phage therapy company Epibiome, Inc.[10][11]

In 2019, the company entered into a strategic collaboration with Janssen Pharmaceuticals (a Johnson & Johnson company) worth up to $818 million to develop CRISPR-Cas3 drugs targeting two bacterial pathogens.[7][12][13][14] Locus received $20 million upfront and up to $798 million in milestones and royalties on net sales.[15]

In 2020, the company signed a $12.5 million partnership with the global non-profit, Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X).[9] In November 2020, Locus had 52 employees;[9] by the end of 2021, it had about 80 employees.[4] As of January 2022, the company and all employees were contained in a single 25,000 square foot research and manufacturing facility.[4]

In 2022, the company closed a $35 million Series B funding round, with participation from Artis Ventures, Tencent, Viking Global Investors, and Johnson & Johnson.[16] Locus announced in September 2022 that it had begun patient treatment in its trial of LBP-EC01, in partnership with the BARDA, for the treatment of UTIs caused by E coli bacteria.[17]

CRISPR CAS3

[edit]CRISPR-Cas3 is more destructive than the better known CRISPR–Cas9 used by companies like Caribou Biosciences, Editas Medicine, Synthego, Intellia Therapeutics, CRISPR Therapeutics and Beam Therapeutics.[7] CRISPR–Cas3 destroys the targeted DNA in either prokaryotic or eukaryotic cells.[12][18] Co-founder, Rodolphe Barrangou, said "Cas3 is a meaner system...but if you want to cut a tree and get rid of it, you bring a chain saw, not a scalpel".[19]

CRISPR-Cas systems fall into two classes. Class 1 systems use a complex of multiple Cas proteins to degrade foreign nucleic acids. Class 2 systems use a single large Cas protein for the same purpose. Class 1 is divided into types I, III, and IV; class 2 is divided into types II, V, and VI.[20] The 6 system types are divided into 19 subtypes.[21] Many organisms contain multiple CRISPR-Cas systems suggesting that they are compatible and may share components.[22][23]

| Class | Cas type | Signature protein | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I | Cas3 | Single-stranded DNA nuclease (HD domain) and ATP-dependent helicase | [24][25] |

| 2 | II | Cas9 | Nucleases RuvC and HNH together produce DSBs, and separately can produce single-strand breaks. Ensures the acquisition of functional spacers during adaptation. | [26][27] |

Therapy development

[edit]The company enrolled its first patient in a Phase 1b clinical trial in January 2020. The trial intends to evaluate LBP-EC01, a CRISPR Cas3-enhanced bacteriophage against Escherichia coli bacteria which cause urinary tract infections.[28] Twenty patients will get a phage cocktail, and 10 will get a placebo.[29] The trial completed before March 2021 and a Phase II trial is expected to start within two years.[2] The company has an agreement the US government's Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority which began in 2020 and provides funding to support Phase II and Phase III trials.[2][9]

Publications

[edit]- Kim, Paul; Sanchez, Ana M.; Penke, Taylor J. R.; Tuson, Hannah H.; Kime, James C.; McKee, Robert W.; Slone, William L.; Conley, Nicholas R.; McMillan, Lana J.; Prybol, Cameron J.; Garofolo, Paul M. (August 9, 2024). "Safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of LBP-EC01, a CRISPR-Cas3-enhanced bacteriophage cocktail, in uncomplicated urinary tract infections due to Escherichia coli (ELIMINATE): the randomised, open-label, first part of a two-part phase 2 trial". The Lancet Infectious Disease. 24 (12): 1319–1332. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00424-9. PMID 39134085.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Buhr, Sarah (December 21, 2018). "Move over Cas9, CRISPR-Cas3 might hold the key to solving the antibiotics crisis". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Eanes, Zachery (March 9, 2021). "Locus using gene-editing technology to get ahead of drug-resistant bacteria". The Herald-Sun. pp. B4. Retrieved August 19, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Barrangou, R. (2019). "CRISPR on the Move in 2019". The CRISPR Journal. 2. Affiliations. doi:10.1089/crispr.2019.29043.rba. PMID 31021232. S2CID 92382436. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c Eanes, Zachery (January 29, 2022). "Locus Biosciences is eyeing immunology for its CRISPR tech". The News & Observer. Vol. 158, no. 29. pp. A6. Retrieved August 19, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Gibney, Elizabeth (January 2, 2018). "What to expect in 2018: science in the new year". Nature. 553 (7686): 12–13. Bibcode:2018Natur.553...12G. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-00009-5. PMID 29300040.

- ^ Brown, Kristen V. (February 24, 2017). "Scientists Are Creating a Genetic Chainsaw to Hack Superbug DNA to Bits". Gizmodo. G/O Media. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Shieber, Jonathan (January 4, 2019). "Up to $818 million deal between J&J and Locus Biosciences points to a new path for CRISPR therapies". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ a b Martz, Lauren (August 31, 2017). "Cutting through resistance". Biocentury. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Maurer, Allan (November 19, 2020). "Gene editing success could turn Triangle startup Locus Biosciences into a billion dollar unicorn". WRAL TechWire. Capitol Broadcasting Company.

- ^ "Locus Biosciences Acquires EpiBiome Bacteriophage Discovery Platform". Genomeweb. July 17, 2018. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ "CRISPR-Cas3 Platform Developer Locus Biosciences Acquires EpiBiome Phage Technology". Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology Nerws. July 17, 2018.

- ^ a b Taylor, Phil (January 3, 2019). "J&J takes stake in Locus' CRISPR-based 'Pac-Man' antimicrobials". Fierce Biotech. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ Molteni, Megan (January 16, 2019). "Antibiotics Are Failing Us. Crispr is Our Glimmer of Hope". Wired. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ Schmidt, Charles (November 1, 2019). "Is Phage Therapy Here to Stay?". Scientific American: 50–57. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ Brown, Kristen (January 3, 2019). "J&J Bets $20 Million on DNA Tool to Battle Infectious Bacteria". Bloomberg. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ Jane Byrne (May 19, 2022). "Bacteriophage producer Locus Biosciences raises $35m in financing". BioPharma Reporter.

- ^ Emily Kimber (September 15, 2022). "Locus Biosciences announces first patient treated in urinary tract infection trial". PM Live.

- ^ Reardon, Sara (2017). "Modified viruses deliver death to antibiotic-resistant bacteria". Nature. 546 (7660): 586–587. Bibcode:2017Natur.546..586R. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22173. PMID 28661508.

- ^ Marcus, Amy Dockser. "A Genetic 'Chain Saw' to Target Harmful DNA". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 6, 2018. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ Wright AV, Nuñez JK, Doudna JA (January 2016). "Biology and Applications of CRISPR Systems: Harnessing Nature's Toolbox for Genome Engineering". Cell. 164 (1–2): 29–44. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.035. PMID 26771484.

- ^ Westra ER, Dowling AJ, Broniewski JM, van Houte S (November 2016). "Evolution and Ecology of CRISPR". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 47 (1): 307–331. doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-121415-032428.

- ^ Wiedenheft B, Sternberg SH, Doudna JA (February 2012). "RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea". Nature. 482 (7385): 331–8. Bibcode:2012Natur.482..331W. doi:10.1038/nature10886. PMID 22337052. S2CID 205227944.

- ^ Deng L, Garrett RA, Shah SA, Peng X, She Q (March 2013). "A novel interference mechanism by a type IIIB CRISPR-Cmr module in Sulfolobus". Molecular Microbiology. 87 (5): 1088–99. doi:10.1111/mmi.12152. PMID 23320564.

- ^ Sinkunas T, Gasiunas G, Fremaux C, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V (April 2011). "Cas3 is a single-stranded DNA nuclease and ATP-dependent helicase in the CRISPR/Cas immune system". The EMBO Journal. 30 (7): 1335–42. doi:10.1038/emboj.2011.41. PMC 3094125. PMID 21343909.

- ^ Huo Y, Nam KH, Ding F, Lee H, Wu L, Xiao Y, Farchione MD, Zhou S, Rajashankar K, Kurinov I, Zhang R, Ke A (September 2014). "Structures of CRISPR Cas3 offer mechanistic insights into Cascade-activated DNA unwinding and degradation". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 21 (9): 771–7. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2875. PMC 4156918. PMID 25132177.

- ^ Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V (September 2012). "Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (39): E2579–86. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109E2579G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208507109. PMC 3465414. PMID 22949671.

- ^ Heler R, Samai P, Modell JW, Weiner C, Goldberg GW, Bikard D, Marraffini LA (March 2015). "Cas9 specifies functional viral targets during CRISPR–Cas adaptation". Nature. 519 (7542): 199–202. Bibcode:2015Natur.519..199H. doi:10.1038/nature14245. PMC 4385744. PMID 25707807.

- ^ "Locus Biosciences initiates world's first controlled clinical trial for a CRISPR enhanced bacteriophage therapy". January 8, 2020. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ "Scientists Modify Viruses With CRISPR To Create New Weapon Against Superbugs". NPR. May 22, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019.