Ljubljana Cave Exploration Society

| |

| Formation | 1910 |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Luize Pesjakove 11, Ljubljana |

Region served | Slovenia |

| Membership | 150 |

President | Matic Di Batista |

| Website | dzrjl.si |

The Ljubljana Cave Exploration Society (Slovene: Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana, DZRJL) is a Slovenian non-profit speleological organization founded in 1910 dedicated to the discovery, exploration, documentation and protection of caves in Slovenia. It is based in Ljubljana, is the oldest still active caving society in the country and is most known for its work in the deep caves of the Kanin mountain range. It discovered, explored and surveyed five caves,[a] deeper than 1,000 meters; the 2019 connection of two such caves reduced the figure to four.[1][2][3][4]

Early history

[edit]

Exploration and documentation of caves in what is now Slovenia began with the publication of the book The Glory of the Duchy of Carniola by Johann Weikhard von Valvasor in 1689, and continued with the works of Joseph Anton Nagel (1748), Franc Anton von Steinberg (1758) and Adolf Schmidl (1854). At the end of the 19th century, the focus of cave exploration was in Škocjanske jame and the Postojnska jama. It was mainly driven by the administrator of the latter cave, Ivan Andrej Perko. After 1885, on behalf of the Ministry of Agriculture in Vienna, Viljem Putik (aka Wilhelm Putick) was exploring the karst in the hinterland of the karst fields in the Inner Carniola.[5]

At the initiative of Perko and Putik in 1910 in Ljubljana the Cave Exploration Society (Društvo za raziskavanje podzemskih jam in Slovenian, Gesellschaft für Höhlenforschung in German) was founded. It was presided by baron Theodor Schwarz von Karsten, at the time regional president of Carniola, crown land in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy.[6][7][8] As only two members of the society had experience in caving, the secretary, Josip Cerk, invited a group of mountaineers and alpinists, called Drenovci, to conduct cave exploration for the society. After the death of Josip Cerk during the winter ascent to Mt. Stol in 1912 Pavel Kunaver took over the exploration leadership.[6][9] Society was divided in two sections: the main Lower Carniolian Section [Dolenjska sekcija], of predominantly Slovenian-speaking members and the Kočevje Section [Gottschee Sektion] of German-speaking members - Gottscheer settlers - they explored the caves in the former Gottschee county till the WWI.[10]

In 1911 Drenovci, within Lower Carniolian Section, began to identify underground inflows into the Krka river and therefore set out to explore the deep abysses, in order to reach the water caves below. In addition to usual caving equipment (roll ladders) they also used rope and mountaineering techniques. The first important achievement was 84 meters deep abyss of Marjanščica. It was followed by Žiglovica (82 m), Krviška Okroglica (93 m), several ice caves on Velika gora, the cave Tentera. At the initiative of Viljem Putik they also explored 200 meters of new tunnel in the north branch of the cave Logarček on Planinsko polje.

The principal photographer was Bogomil Brinšek, who used flat magnesium ribbon wound around a hammer as a source of cave illumination. His artistic depiction of mountain and cave scenes, often in pictorialist style attracted many to photography, first of all Ivan Tavčar and Josip Kunaver.[11][12][13][9]

The society became known in the wider area, it was invited to explore caves in Pazin and Baderna, Istria, where the main achievement was the descent in 97 m deep cave Golešička (Golešnica), in search of an underground water source. Until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 the society explored 133 caves.[11]

WWI interrupted society's activities, Bogomil Brinšek was killed in the first days of the war, but it did not stop the speleological work of the society members. Pavel Kunaver, as a non-commissioned officer of the Austro-Hungarian army, participated in the exploration and adaptation of caves in the Karst area for military needs. Later he joined the special caving group led by Lieutenant Ivan Michler, also a society member, to explore caves in Trnovski gozd and Banjšice, in the immediate hinterland of the front line in the Battles of the Isonzo campaign. In 1917, Kunaver and Michler explored over a hundred caves for military purposes. On August 31, 1917, they in one go explored the abyss Roupa to the depth of 146 meters, which remained the society's record achievement until 1965.[11]

Between the two wars

[edit]In the two decades after the World War I, DZRJL established itself as a full-fledged caving organization. During 1,264 field trips 742 caves were explored.

Pavel Kunaver published the book Karst world and its phenomena [Kras in kraški pojavi] in 1922, the first Slovenian popular science book about Karst, to awaken the Slovenian public to caving and speleology. But the timing was not yet suitable. His second book In the Abysses [V prepadih, 1932] also did not meet the expected response. DZRJL activity resumed in 1924, the society changed focus from topographical discovery of the underground to the scientific study of karst phenomena. The seat of the society was established at the Zoological Institute of the University of Ljubljana - since 1927 DZRJL was chaired by the zoologist Jovan Hadži. In the summer 1925 the first caves after WWI were explored, Zlatica and Govic, the partly submerged spring cave, both above Lake Bohinj and 4 caves in the vicinity of Škofja Loka. In 1926 the cave Županova jama was discovered by Josip Perme, the mayor of Ponova Vas, which soon became one of the most visited Slovenian show caves. In the same year it was explored and surveyed by DZRJL (it is 710 meters long and 73 meters deep) and the society's member Valter Bohinec published a monograph about the cave, the first speleological treatise in Slovenian. It includes extensive instructions on the work of a physical speleologist in a cave. In 1927 Roman Kenk and Albin Seliškar have set up one of the first laboratories worldwide for the study of cave fauna in the cave Podpeška jama.[14][15][16]

In 1929 the society conducted exploration of caves in the wider area of Loško polje. The main achievement was the exploration and survey of the inner parts of Križna jama, discovered in 1926. More than 5 km of water tunnels have been explored and surveyed. In 1931 DZRJL explored the cave Vjetrenica in Herzegovina and surveyed several kilometers of tunnels, making it the longest cave in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. 1932 - the search for Lipertova jama, lost after the death of its discoverer, Viljem Putik in 1929, was restarted, and on August 12 the cave Krastača, later the second entrance of Najdena jama, was found. In 1933 Albin Seliškar performed one of the first cave dives in the world in an atmospheric pressure diving suit, in Pod stenami sinkhole at the north edge of Planinsko polje. The middle of the 1930s was the boom time for the Logatec branch of DZRJL. Under the leadership of Ivan Dolar, they systematically explored caves in the wider surroundings of Logatec and penetrated to the end of Blata branch in Križna jama. In 1937, while the DZRJL group was scouting the area to find Lipertova jama, Alfred Šerko Jr., with the help of a survey based on the land cadastre, produced by mining engineers Kersnič and Lučovnik from Ljubljana, discovered the entrance to this cave (Alfred Šerko Sr., his father,[17] was a renowned Slovenian neurologist and psychiatrist). The upper part of the cave exactly matched the Putik's description and his map, but as the water tunnel was much smaller, Šerko concluded the cave is not the same and named it Najdena jama [Found cave]. In 1938 Šerko rearranged the DZRJL cave registry - he sorted the archive of excursion records by cave, gave caves cadastral numbers and compiled the List of caves in ozalid technique. In the late 1930s Šerko and Ljubo Podpac organized systematic exploration of caves along the border with Italy. Detailed search for caves on Pokojišče Plateau and on Begunjski Ravnik has also been made. In 1939 Ivan and Dušan Kuščer made a dive into Malo okence (8 meters deep) and Veliko okence (the first siphon, 4 meters deep and 10 meters long) karst springs of Ljubljanica river near Vrhnika with diving equipment of their own design and manufacture. From 1926 the principal DZRJL photographer was Franci Bar, who used flash powder as the main source of underground illumination. He also perfected the cave stereo photography.[14][18][19]

Najdena and Žankana jama

[edit]After the turbulent times in the 1940s the society reached the second peak in the 1960s with the discovery of a large cave after the tight passage at the end of Najdena (Lipertova) jama was broken in 1963, and the exploration of deep caves in Slovenia, such as Triglavsko brezno and Medvedova konta on Pokljuka plateau and the deepest cave in Yugoslavia, Žankana jama.[20]

During the Second World War, Valter Bohinec and Jovan Hadži hid the society's archive in the premises of the National and University Library in Ljubljana. As the Slovenian anti-Nazi resistance units often used caves as hideouts, cave locations and maps in this archive were of great military importance. The archive of the Kočevje Section of DZRJL was stored in Kočevje and was burnt in December 1943 during the Battle of Kočevje. Only a few fragments survived, stored in the main archive (of the cave Vodna jama pri Klinji vasi).[10]

In 1945 the DZRJL activity resumed, exploration began also in the now again accessible Littoral Karst. It was reflected in the book by Šerko and Michler: Postojnska jama and other attractions of the Karst.[21] In 1948 the society suffered a great loss with the sudden death of Alfred Šerko. During a speleological field trip in Istria he got out of the car he was driving and as he was still holding the door handle the lightning hit the car, killing him while the other passengers in the car remained unharmed.[22] His role was taken over by Ivan Michler and systematic exploration of the underground between Planina and Postojna began. Pavel Kunaver successfully promoted caving by organizing field trips to caves as part of the extracurricular activity at the high school in Ljubljana where he was a teacher. In 1950, in Planinska jama, a bifurcation was discovered in the Rak river arm of this cave. In 1951 in the Velika Paradana ice cave a new pit was discovered, cave depth was increased to 120 m. The first major discoveries were made, after almost ten years, in the cave network of Postojna Cave. In the same year, the DZRJL Postojna branch was established. Its main exploration area was the cave behind the Predjama Castle, where a large cave network was discovered. In 1954, the First Yugoslavian Congress of Speleology was held in Postojna, organized in large part by members of DZRJL. To conform to the statute of the Speleological Association of Yugoslavia, which required cover organization in every of the Yugoslavian federal republics (regions), DZRJL was renamed to Cave Exploration Society of Slovenia (DZRJS).

Due to different views on caving and the operation of the society, there were open disputes between the young and old generation. Dušan Novak and Miran Marussig, of the young generation, were expelled from the society in 1954. In 1955, with Marussig's help, Novak founded the Speleological Section of the Railway Alpine Club, the second caving organization in Ljubljana, while Marussig returned to DZRJS.[23] In 1957, the Postojna branch of the society became independent as the "Luka Čeč" caving society. In 1958 they organized, together with DZRJS a successful expedition to one of the deepest caves, Jazben (- 334 m), and discovered several new tunnels. In 1959, Kazimir Drašler, Jože Štirn and Jože Mušič dived through the 10 meters long siphon in Veselova jama near Cerknica (source of Žerovniščica river), and Mušič took the first photographs from behind the siphon in Slovenian caves.[18] In 1960, the members of the society explored Brezno pri Medvedovi konti on the Pokljuka plateau with one of the largest known cave halls at that time. In the same year the first exploration of caves on the high mountain plateau (Kriški podi) of the Julian Alps took place.[24] In 1961, a large all-Slovenian DZRJS expedition reached the bottom of Triglavsko brezno (Mt.Triglav Abyss, elevation 2377 m, depth 260 m). In 1962, local branches of DZRJS in Slovenia became independent caving societies, registered in their local municipalities, while DZRJS was renamed to Jamarski klub Ljubljana [Ljubljana caving club], to which the word Matica (parent, JKLM) was added in 1966.

In the spring of 1963, a team of young members of the society made their way into the inner parts of Najdena jama. The cave, discovered by Putik in 1886 as Lipertova jama, later lost and in 1937 rediscovered and renamed by Šerko, was 200 meters long, but had a passage with strong air current, too narrow to pass, at the end. It took several months to dig it through. Already in 1963 the cave was close to 1 km long, in 1964 further discoveries: Putikova dvorana, Piparski and Borisov rov brought the total length to over 2 km. In the summer of 1963, at the initiative of the society member Jurij Kunaver, a geographer and the son of Pavel Kunaver, the first expedition to Mt. Kanin in the Western Julian Alps took place. In 1965, the members continued the exploration and survey of Najdena jama. They were exploring the area of Lanski vrh and continuing their research in Kanin and on Mount Krim. On Kanin, in the Primoževo brezno (-175 m), the society's depth record in a completely independent discovery was surpassed. After the 4th International speleological congress in Ljubljana and Postojna (1965), organized to a great extent by the society the a change of generations in the society leadership took place. In 1966 several pits over 100 m deep have been discovered and explored on Kanin. A new society's depth record in an own cave was achieved in Primoževo brezno, -197 m. A large team took part in the expedition to Pološka jama, where JKLM members discovered the main continuation. Milan Orožen and Ugo Fonda dived through the 12 meter long siphon between Črna and Pivka jama. It was the beginning of modern diving in Slovenian caves.[18][25] Under the leadership of Tomaž Planina after 1967 expeditions to deep caves followed. The same year Ljubljanska jama [Ljubljana Cave] under Mt. Kogel in the Kamnik–Savinja Alps was discovered. In 1968, the Lipiška jama with its 210 m deep clear vertical shaft, and several large pits on Kanin were explored. Members of the society reached a depth of 300 m (the cave extends upwards from the entrance) in Pološka jama.[26]

The greatest impact had the 20-member expedition in 1968 to Žankana jama near Rašpor, in Istria.[27][28] It is a sinkhole - after initial smaller shafts a large, 200 m deep inner abyss opens up.[29] Between WWI and WWII Istria belonged to Italy, the cave was named Abisso Bertarelli, explored in 1924 and 1925.[30] With a depth of 450 m, it was known, from 1924 to 1926, as the deepest cave in the world.[31] After 1959 it was the deepest cave in Yugoslavia, before Gotovž (also in Istria, −420 m) and Jazben (Slovenia, −365 m).[32] As it often happened that Italian pre-WWII surveys of caves in the littoral part of Slovenia showed greater depth than it actually was, one of the goals of the expedition was to make a new survey. The expedition reached the previously known bottom of the cave, at −346 m and continued through a long low horizontal tunnel, till the Slovenian siphon, at −361 m, according to the new survey. This depth moved the cave to third position on the Yugoslavian cave depth scale. At the end of 1968 Primož Krivic, Marjan Juvan and Renato Verbovšek explored and surveyed the entrance part of the cave Mala Boka near Bovec and entered it into the Slovenian cave registry. The following JKLM expeditions to Gotovž and Jazben reduced the depth of Gotovž to 320 m and of Jazben to 334 m – and so Žankana jama regained top of the list.[27] These achievements positioned JKLM to the top of Yugoslavian cave exploration.[33] In 1969 members of JKLM joined an international expedition to Poland, to Jaskinia Wielka Śnieżna and to Jaskinie Psie, a survey of the Eastern tunnel in Kačna jama near Divača was made and three society members participated in the largest ever international expedition to Gouffre Berger in France. On October 26, Anton Suwa, a member of the society, perished during the survey of the cave Pekel near Šempeter in Savinjska dolina.[20][34]

Caves on Mt. Pršivec

[edit]

The replacement of caving roll ladders for the descent and ascent in vertical cave sections by single-rope technique, where the equipment is several times lighter and less cumbersome made possible a shift of society's focus from lowland caves to mountain caves. After Pološka jama below the southwestern outskirts of the mountain ridge south of Lake Bohinj and the first forays to the caves of Kanin mountain ridge in the 1960s, in the 1970s and 1980s the karst on the slope of Mt. Pršivec (pron. Prsheevats, 2056 m) north of Lake Bohinj became the main exploration area of the society.[35]

1970 - in Ljubljanska jama, the society's depth record in a completely independent discovery has been exceeded several times, to 279 m. For the first time in Yugoslavia, a depth of 500 m was surpassed in Pološka jama, and after twenty years, a cave from this country reappeared on the world cave depth scale. Divers reached new depths in Divje jezero, Žerovnica, Postojnska jama, Tkalca jama and Planinska jama. DZRJL members participated in new discoveries of the Piaggia Bella cave network on the French-Italian border. In 1971, exploration in the cave Pološka jama increased the depth to 685 m, the Yugoslavian depth record. For a short time, the cave was among the twenty deepest in the world and the first among the caves explored from the bottom upwards.[26]

In 1972, the society returned to its traditional name: Ljubljana Cave Exploration Society (DZRJL). In September an expedition to Brezno pri gamsovi glavici [Abyss at the chamois head] above Lake Bohinj took place. The cave was discovered in 1969 by the Jamarski klub Železničar [Railway caving club] and explored to a depth of 40 m in 1969, to −170 m in 1970, to −475 m in 1971, and to −615 m in August 1972, when Jurij Andjelić-Yeti, of DZRJL, also participated.[36][37] As the pit depths were only estimated, the task of the DZRJL expedition, which included Yeti, was to survey the cave and to search for an eventual continuation. The cave depth was corrected to 444 m, which was still the second deepest in Yugoslavia, and a continuation was also found.[36] In the coming years more DZRJL expeditions deepened the cave to 819 m.[38] Jože Pirnat published Caving Technique [Jamarska tehnika], the first Slovenian book on this topic. In 1973 several deep caves have been discovered on Kanin, the outflow siphon in Pivka jama was dived through and Rado Smerdu made the 8-millimeter cave film In a Sunless World.[26]

In 1972, Primož Jakopin of DZRJL proposed valuation of caves not by length and depth but by volume.[39] In 1974 he designed a 3D model for the representation of caves and, with Jaka Jakofčič, made the first 3D cave survey, of Skednena jama. By 1979 he developed the software tool for the 3D model and from 305 vertices in 51 cross sections the parameters for this cave were computed: length 205 m, surface area 8900 m2 and volume 6,500 m3 with error estimate below 5%. In 1981 a larger cave, Mačkovica, located in the same area as Skednena jama, was surveyed by Jakopin and a team of 9. They used two large protractors with narrow flashlight beams on top to measure the angles to inaccessible ceiling points from the pairs of known floor points. The 3D model consisted of 106 cross sections and 709 vertices; it produced a length of 650 m and volume of 38,800 m3 with volume error estimate below 2%.[40][41] In 1984 Daniel Rojšek of DZRJL and his team used this method to survey a 54 m long segment of the large Martel's Hall at the end of Škocjanske jame caves. It produced a volume of 220,000 m3,[42] one tenth of the entire hall volume (2,200,000 m3), surveyed by English cavers in 2018.[43]

In August 1974 the first fatal cave diving accident in Yugoslavia occurred in Tkalca jama, Slovenia. Janko Petkovšek of Logatec Caving Society did not return from a dive in the terminal siphon. Two DZRJL members of the rescue team, Boris Sket and Anton Praprotnik, managed to dive through the 26 meters deep and 147 meters long complex outflow siphon for the first time. 2 km long water tunnel followed but Petkovšek's body was never recovered.[18]

In 1975 DZRJL team dived through the siphon of the Boka spring and through the 240 m long outflow siphon in Pivka jama (part of Postojnska jama cave network), after which 300 m of dry tunnel followed. In 1976 after five years of work, the upper entrance to Pološka jama was opened, which increased cave depth to 705 m. By the end of the year, more than 300 caves have been explored on Kanin. In 1977 a 120 m high chimney was climbed in the Hanke channel of the Škocjan Caves. In 1978 a depth of 612 m was reached in Brezno pri gamsovi glavici, and 758 m in 1979. Rado Smerdu shot a 16-millimeter film Untrodden Trails and participated in making of the film Where are those paths about the society's biologist Egon Pretner. In 1980 on Mt. Pršivec above Lake Bohinj, Majska jama was discovered and explored to a depth of 420 m. Two members of the society took part in the Yugoslavian expedition to the deepest cave of the time: Gouffre de la Pierre Saint Martin (-1332 m) and to Gouffre Berger. Rado Smerdu, together with co-author Vilko Filač, received a special jury award at the 3rd International Speleological Film Festival in La Chapelle-en-Vercors, for the film Kje so tiste stezice [Where are those footpaths].[44] From 1981 to 1983 exploration continued on Mt. Pršivec, in Brezno pri gamsovi glavici and in Majska jama, where the depth of 592 m was reached. In 1984 Rado Smerdu, president of the society, drowned while canyoning in the Predaselj gorge of the river Kamniška Bistrica. From 1985 to 1988 society members visited Antro del Corchia (-1210 m, in the Apuan Alps) and Spluga della Preta (-877 m, on the Lessinia plateau above Verona). On Pršivec Pingvinovo jama, Brezno Martina Krpana, Cefizljeva jama and Botrova jama were explored. The latter was connected with Brezno pri gamsovi glavici, increasing its depth to 819 meters. The main photographer of the society in the 1970s and 1980s was Tomaž Planina, a student and successor of Franci Bar. He mastered electronic flash cave lighting as a replacement of air-polluting flash powder cave illumination.[35]

Kanin, Pokljuka and Poljana caves

[edit]

In the past decades the society's most important task became the discovery and exploration of caves on the plateau at 2200–2350 meters above sea level (800 known caves, as of 2022), below the peaks of Kanin and Rombon mountain ridges on the Slovenia/Italy border, where around one tenth of all the caves in the world, deeper than 1000 meters, is located.[45] After 2005, the main project was "Kanexit", the connection of these caves to the cave Mala Boka - main entrance at the elevation 433 m, upper entrance (BC4 cave) at the elevation of 1730 m - above the valley of the river Soča. It would result in a cave, 1900 meters deep.[46][47]

In 1989 members of the society participated in the exploration of Skalarjevo brezno on Mt. Kanin, at the time the deepest Yugoslavian cave, where the Slovenian team reached a depth of 911 m. At the invitation of the cavers from Trieste, in October Franci Gabrovšek and Gregor Pintar took part in the "-1000" campaign in the Črnelsko brezno on Mt. Rombon, where the depth limit of 1000 meters has been exceeded for the first time in Slovenia. In January 1990 the society participated in the rescue operation in the same cave, where a Trieste caver perished while rescuing an injured colleague. DZRJL team discovered the entrance to the cave Vandima (grape harvest in Slovenian littoral dialect, from vendemmia in Italian) on Mt. Rombon on July 28. In 1991 the society's summer caving camp was moved from traditional Pršivec above Lake Bohinj to the Rombon plateau. In Vandima, four branches were explored in 1991 and 1992, which lead to depths of 398, 600, 650 and 550 m. In seven field trips from March to July 1993 in Vandima, they reached a depth of 1042 meters, for the first time the thousand-meter limit was reached by Slovenian cavers. Society consolidated its position at the top of high mountain cave exploration in the country. In 1994 the bottom of the vertical in Brezno pod Velbom [Abyss below the Vault] was reached, at the time the world's deepest individual pitch (vertical drop) within a cave, 501 meters. As of 2022 it was seventh in this ranking.[48] In 1996 society members took part in international caving expeditions to São Vicente cave in Brazil, Italian expedition to La Venta canyon caves in Mexico and a caving expedition to Pakistan.[49]

In 1997 the society's summer camp was moved from Rombon to Kanin. The bottom of Brezno pod Velbom was reached, at -852 meters. In the fall, the society organized an independent caving expedition to caves of Oman, 4.5 km of new cave tunnels were explored and surveyed. The biggest cave, Konof, was 223 meters deep and 1508 meters long. DZRJL cave registry, headed by Dorotea Verša, created a caving mailing list, which soon became the main means of information exchange among Slovenian cavers. In 1998 numerous field trips to Gorjanska jama above Gorje near Bled extended the cave by 2 km. In Najdena jama, after many years, a continuation is found again. Society took part in further exploration in Skalarjevo brezno on Kanin. In October Jože Pirnat discovered the entrance to Renejevo brezno [René Abyss, Rene for short] on Kanin plateau. It was named after Renato Verbovšek - Rene, who perished in a car accident a few days before the discovery. In 1999 14 field trips deepened this cave to 750 m and Marjan Baričič discovered the P 4 or Brezno rumenega maka [The Abyss of the Yellow Poppy]. With the help of the Norik-sub diving club, the first siphon in the cave Ponor polne lune [the Full Moon Sinkhole] on the Banjšice Plateau was overcome and the terminal siphon at a depth of 430 m, 2 km from the entrance, was reached.[3][49]

2000 - the length of Najdena jama was extended to over 5 km. Renejevo brezno became the second society's cave, deeper than 1000 m.

On April 19, 2001, DZRJL left the Speleological Association of Slovenia (JZS). When the JZS was founded in 1962, the society made its archive, the cave registry, available to the newly founded association. Cave registry thus became common, with the agreement that DZRJL would retain control over it. Tensions between the two organizations burst into the open in 1990, when the voting rule was changed at the yearly General assembly of JZS, from 10 cavers one vote, which provided additional weight to more active caving clubs, to one member of the association one vote. In 1997 General assembly of JZS changed the statute of the association, the clause that the head of the cave registry is proposed by DZRJL and confirmed by the General assembly of JZS, was scrapped. After 1997, the head of the cave registry, member of DZRJL Dorotea Verša, retained her position, but at the JZS General Assembly in 2000, when the DZRJL candidate for the presidency of the JZS was also not elected, it was clear that the agreement was at an end. DZRJL withdrew all the documents made by its members from the common archive, replaced them with replicas and, after the last attempt of reconciliation failed, left JZS. As of 2024 JZS had 36 member organizations with about 700 cavers. Most visible absentees were DZRJL (150 members) and JD Dimnice (Koper, 40 members).[50][51]

Also in 2001, Renejevo brezno was explored to -1068 m, Dean Pestator made the caving movie Vrtiglavica [Vertigo], shown in several climbing/caving film festivals. In 2002 and 2003 society explored the cave Lobašgrote near Črni Potok pri Kočevju; on Kanin in Renejevo brezno the search for continuation in the collapse at -1000 continued. 2004 - in the same cave the narrow passage Binina pasaža [Bina's crevasse] was overcome and the cave continued to -1114 m. DZRJL expedition to Tunisia explored, with local cavers, several pits above Zaghouan and the Mine Cave. 2005 - on Kanin two deep caves, Rovka and Brezno pri lepih žlebičih were explored and surveyed, near Strahinj the cave Velika Lebinca. In Renejevo brezno the water stream (in the tunnel named Kaliktar, coll. word in Slovenian for Collector) was discovered. Society members participated in an expedition to caves in Slovakia. In 2006 Renejevo brezno on Kanin in Copacabana hall the terminal (later named Matt's) siphon, at -1240 m was reached, at the level of the central Kanin plateau underground water basin.[47]

Jurij Andjelić discovered the cave Brezno spečega dinozavra [Abyss of the Sleeping Dinosaur], elevation 2310 meters, 400 meters NE of Rene, just below the ridge of Visoki Kanin, 2587 m, and 330 meters (to the NWN) from the border with Italy. In 2007 a notable achievement was the exploration of Krasja jama above the Soča river valley. In 2008 the exploration in the Sleeping Dinosaur continued to the depth of 300 meters, where the Brezno T-Rex (Tyrannosaurus Rex Abyss) ended in a collapse cone. Further exploration was abandoned and the cave was not registered until 2022. Society members participated in expedition to Prokletije in Montenegro, where 30 new caves were discovered. 2009 - Brezno treh src [The Abyss of Three Hearts] was discovered on Mt. Snežnik. In 2010 exploration continued in the Abyss of Three Hearts, nearby Brezno sijočih zvezd [The Abyss of the Shining Stars] was discovered and explored. At the initiative by Matt Covington exploration on Pokljuka mountain plateau began with the cave Evklidova piščal [Euclid's flute], elevation 1550 meters.[52]

2011 - together with cavers from Ajdovščina and Trieste the narrow passages in the cave P 4 on Kanin were widened all the way to the bottom, including the final one. In 2007 Rok Stopar, of Dimnice caving society (Koper) free-dived in the siphon of Renejevo brezno, at -1240 m. He discovered that the submerged tunnel of reasonable proportions continues 1 m below the surfaces, with clear water. After a long unsuccessful search for a caving diver, capable of diving at this depth, Matt Covington, a speleologist and a rookie diver from Arkansas, USA, volunteered and dived in the siphon on November 11, 2011. The water had 2.7 degrees C, the dive lasted 12 minutes, reached 10 meters deep and 30 meters far. The submerged tunnel, 7 x 4.5 meters, descended at an angle of 20° in the WSW direction, two chimneys were found, one explored, it reached the surface. Tunnel continuation was visible, in the same direction, at the same angle.[53] In the spring of 2013, Matic Di Batista and Matija Perne took part in an expedition to the Chevé Cave in Mexico. Exploration of P 4 cave on Kanin resumed till the impassable crevice with strong air current, at the depth of 458 m.[54] On Pokljuka ridge two caves with entrances 25 meters apart were discovered: Platonovo šepetanje (Plato's whisper, elevation 1861 m) and Trubarjev dah (Trubar's breath, elevation 1853 m). 2014 - in October a 23-member cave team, of the society and 11 other caving clubs (ten from Slovenia, one from Croatia), supported by 10-member DZRJL surface team, visited Matt's siphon at the bottom of Renejevo brezno on Kanin. The diver, Simon Burja of DZRJ Simon Robič Domžale, reached the depth of 82 meters, at the distance of 250 meters. The tunnel of clear water, of the same size, continued at the same angle and direction: 7 x 4.5 m, -20°, WSW, with no end in sight. The cave depth increased to 1322 meters.[55] At the end of May 2015 the cave Brezno na Toscu, elevation 1965 m, above the Pokljuka plateau in the Julian Alps, discovered and registered in 1959, with a 100 meters deep entrance pit, was explored. Till the early 2016 it reached the depth of 472 m and length of 1098 m.[56]

From January to May 2016 society's veterans dug through a series of impassable meanders in the Galacijevka (Škrlovo brezno) cave, 250 m SE from Najdena jama, and connected the two caves at a depth of 65 m. Galacijevka became the third entrance of Najdena jama - the second, the cave Krastača was connected in 2004 by cavers from Borovnica and from the Railway caving club. In July the cave Romeo (elevation 1881 meters) was discovered in the Pokljuka ridge, 200 meters from Trubarjev dah and Platonovo šepetanje, in a terrain difficult to pass - steep slope, overgrown with creeping pine. At the end of December a 20-member team (14 of DZRJL, 6 from Croatia) reached the depth of 1002 meters in the cave P 4 on Kanin. At the depth of 950 meters they discovered arguably the biggest hall of Kanin caves, Infinitum, with the approximate volume of 220.000 m3, one-tenth of the largest Slovenian underground space, Martel's Hall at the end of Škocjanske jame caves.[57][43] In January 2017 the caves Trubarjev dah and Platonovo šepetanje in the Pokljuka ridge were connected. In August 2018 Brezno na Toscu was explored till the length of 1870 m and depth of 581 m. Further exploration was abandoned due to difficult access both to the entrance and to the bottom.[58] The same, due to ice at the bottom, happened to the cave (Su)Rovka on Kanin, at the length of 1596 m and the depth of 385 m. Also in August the cave Romeo in the Pokljuka ridge was connected to Trubarjev dah and Platonovo šepetanje.[59]

In the beginning of 2019 an idea to find a new, reasonably small speleologically unexplored area in NW Slovenia, where many new caves could be found within limited time and effort, circulated at the society. After the analysis of LiDAR high-resolution maps where sharp-edged abyss-entrance-like depressions in the terrain are clearly visible, Matic Di Batista selected an area around Planina Poljana [Poljana mountain pasture, elevation 1470 m], below Mt. Raskovec (elevation 1967 meters) in the mountains between Bohinj and Tolmin. It covers about 17 km2 - 3.1 km (S-N) x 5.6 km (W-E) with majority of entrance-like features positioned in a 3 km2 (1.4 km by 2.3 km) pocket WNW of Poljana. The area is well accessible - an hour and a half drive from Ljubljana, one hour on foot - but still largely neglected, as it is, like the Pokljuka ridge, overgrown with dwarf pine.[60][61][62][63] Prior to 2019 eleven caves were registered in the area, in 1958 (4), 1976, 1990, 2011 (2) and 2017 (3) - by the end of 2019 the society discovered and explored 30 new caves with a total length of over 5 km. The achievement was facilitated, to a great extent, by help of locals who made one of the pasture huts available for overnight stay.[46][60] In April 2019 three DZRJL members, Matic Di Batista, Špela Borko and Jure Bevc took part in the expedition to the Chevé Cave in Mexico.[64] The cave Trubarjev dah on Pokljuka reached the length of 6200 meters and the depth of 614 meters. In August the caves Renejevo brezno (6 km long) and P 4 (also 6 km long) were connected at the depth of 1000 meters below the entrance of Rene, producing the longest cave on Slovenian side of Kanin, surpassing long-time leader Mala Boka - BC4.[65][46][66][67] In August 2020 the terminal siphon in the cave P 4 on Kanin was reached at the depth of 1102 meters in the Ipanema hall, elevation 1019 meters, presumably at the same level as the nearby Matt's siphon in Renejevo brezno. The cave LJ 29, also on Kanin, was explored to the depth of 415 meters.[68] In September the cave Platonovo šepetanje on Pokljuka reached the length of 2352 meters and the depth of 569 meters. Pokljuka ridge caves - three connected caves: Trubarjev dah, Platonovo šepetanje and Romeo (cumulative length 9584 meters, depth 643 meters) plus Evklidova piščal in the immediate vicinity reached the length of 12000 meters and depth of 760 meters. In the Bohinj mountains, in Planina Poljana area 26 caves were discovered and explored.[69]

In August 2021 the exploration of Brezno spečega dinozavra [Abyss of the Sleeping Dinosaur] resumed. Two days before the end of the society's summer camp on Kanin, which failed to meet the expectations, a survey team of four discovered a window above the terminal shaft on the north side of the bottom T-Rex hall, at -300 meters. Cave continued to the north, in the direction of the border with Italy. They reached the depth of 350 meters where the trip ended because the rope ran out. The next day a team of five advanced to -400 meters, where the cave had two continuations - in a wet meander and in a large, dry canyon. The third trip, a week after the summer camp ended, followed the wet meander and reached the depth of 500 meters, the fourth trip, another week later, ended at -750 meters. Fifth trip in September 2021 yielded the depth of 1040 meters, at the narrow meander. Till the end of 2021 the cave depth increased to 1082 meters, with a siphon at the bottom. Several continuations, after the dry canyon at -400 meters, remained to be explored.[70] In August 2021 a society member took part in the international expedition to the cave Boybuloq in Uzbekistan.[71] On Planina Poljana area 20 caves were discovered and explored, among them 4-P, over 1 km long.[62] In 2022, from May Day to the end of the year, a new cave close to Robidišče, a village at the far western edge of Slovenia, 200 meters from the border with Italy, was discovered and explored. It is a multi-level cave with an underground stream, 2053 meters long and 266 meters deep.[72] The biggest Poljana cave Grvn (8 km), named after local expression for gorvodno [upstream], with a network of large fossil phreatic passages 400 meters below the surface, was connected to Rajža cave, producing a length of 10 km, ninth longest among caves in Slovenia.[73][46] Exploration of the Abyss of the Sleeping Dinosaur on Kanin continued, the depth of 800 meters was reached in the new, NW branch. In 2023 this branch split into two and siphons were reached in both continuations. At -1075 meters in the NWN side, which crossed the Slovenioan-Italian border just before the siphon, and at -1074 meters in the other side. The elevation of the three siphons was at around 1230 meters above sea level, 200 meters higher than the elevation of Copacabana/Ipanema water level at the bottom of Renejevo brezno and P 4 caves.[74] From March 2019 to November 2023 97 new caves were discovered and explored on Planina Poljana.[63]

People

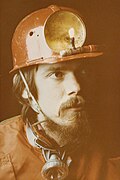

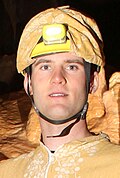

[edit]Since 1910 many people joined DZRJL, some for life, some for a few years. Until 2010 the number of members came close to 1000.[75] Optional portrait gallery of several members is available below. Numbers indicate the year when the person joined the society.

|

Up to 2024 there were 20 presidents of the society, two have served twice, the longest serving was Jovan Hadži, from 1929 to 1948. Numbers in the following optional list indicate the year the person was elected president of the society.[76]

| DZRJL presidents | |

|---|---|

| Theodor Schwarz von Karsten | 1910 |

| Josip Mantuani | 1923 |

| Mate Hafner | 1924 |

| Jovan Hadži | 1929 |

| Albin Seliškar | 1948 |

| Ivan Michler | 1949 |

| Valter Bohinec | 1954 |

| Jurij Kunaver | 1965 |

| Valter Bohinec | 1966 |

| Tomaž Planina | 1967 |

| Matjaž Puc | 1971 |

| France Osole | 1972 |

| Rado Smerdu | 1981 |

| Tomaž Planina | 1984 |

| Joerg Prestor | 1986 |

| Gregor Pintar | 1990 |

| Rafko Urankar | 1997 |

| Matjaž Pogačnik | 2003 |

| Primož Presetnik | 2007 |

| Mitja Prelovšek | 2011 |

| Jure Košutnik | 2014 |

| Matic Di Batista | 2019 |

Publications

[edit]In 1959, the first issue of the society's journal Naše jame [Our Caves] was published.[77] It remained the scientific and professional publication of DZRJS until 1970, when it was taken over by the Speleological Association of Slovenia (founded in 1962). Glas podzemlja [Voice of the Underground], the society's less formal annual publication, is a reflection of the time and activities of the DZRJL members. Since 1969 30 issues were published.[78]

The first Caving Handbook (Jamarski priročnik in Slovenian), the only complete one, was published in 1964 by the publishing house Mladinska knjiga in the collection Nature and People, but it was written by nine authors, all members of the society: Ivan Gams, Zdravko Petkovšek, Miran Marussig, Jože Štirn, Boris Sket, France Osole, Franci Bar, Uroš Tršan and Valter Bohinec. It covers 100 pages and is divided into 12 chapters: Research of cave forms and cave formation (I.G.), Cave metereology (Z.P.), Hydrological measurements in caves (M.M.), Diving in speleology (J.Š.), Biological research in caves (B.S. ), Cave - archaeological site (F.O.), Organization of cave excursions (I.G.), Caver's personal equipment and exploration tools (M.M.), Survey of karst caves (M.M.), Photography in caves (F.B.), First aid for cavers in case of accidents (U.T.) and From the history of karst cave exploration in Slovenia (V.B.).[79]

The 131-page caving handbook Ne hodi v jame brez glave (Don't go into caves without a head by Rafko Urankar, France Šušteršič, Marko Simić and Anton Praprotnik) was published in 2001. Topics covered: Caving technique, Documenting caves, Using topographic maps, Cave protection and Dangers in caves.[80]

As authors or co-authors, the members of the society created numerous publications from the field of speleology.[81]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Cave names used in this article follow names, used in the Slovenian Cave Registry,[62] a family of connected caves is referred to as cave network. Widely used, usually much shorter synonyms are sometimes given in place of official names, the two examples are Krastača instead of Brezno v Tratnikovem koniku (cave registry number 213) and Rene instead of Renejevo brezno (7090).

References

[edit]- ^ Petelin, David (12 May 2021). "1910 – Ustanovljeno Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana" [1910 – The Ljubljana Cave Exploration Society was founded] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Zgodovina na dlani [History in the palm of your hand]. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Korošec, Maja (19 September 2021). "Ko stopiš za vogal, za katerega ni pogledal še nihče, je občutek res svojevrsten" [When you step around a corner that no one has looked at before, the feeling is really unique] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: 24ur.com. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ a b Borko, Špela; Di Batista, Matic; Covington, Matthew (24–31 July 2022). Connecting the void below Mt. Kanin (PDF). 18th International Congress of Speleology. Proceedings - Vol. II - Caving and explorations. Savoie Mont Blanc: UIS. pp. 41–44. ISBN 978-2-7417-0692-2. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ Burger, Betka (25 September 2024). "Jama Dlvn: presegli magično globino tisoč metrov" [The magical depth of thousand meters was exceeded in Dlvn cave] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: DELO. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ Kranjc, Andrej (1997). "Karstology and speleology in Slovenia". Annales. Series historia naturalis. 7 (11). Science and Research Centre of the Republic of Slovenia (Koper): 95–102. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Zgodovina DZRJL" [History of DZRJL] (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Gspan-Prašelj, Nada (2001). "Schwarz von Karsten, Theodor Frh. (1854-1932), Beamter und Politiker" [baron Schwarz von Karsten, Theodor (1854-1932), civil servant and politician]. Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon (in German). Vienna: Austrian Centre for Digital Humanities and Cultural Heritage. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Kunaver, Pavel (1970). "Ustanovitev Društva za raziskovanje jam Slovenije leta 1910" [Foundation of the Society for the Exploration of Caves of Slovenia in 1910] (PDF). Naše jame (in Slovenian). 12. Društvo za raziskovanje jam Slovenije: 9–14. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ a b Škodič, Dušan (27 March 2015). "Slovenski fantje, ki so rušili stare nazore" [Slovenian boys who were challenging old views] (in Slovenian). Kranj: Društvo gore-ljudje. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ a b Planina, Tomaž; Rojšek, Daniel; Skoberne, Peter; Smerdu, Rado; Šušteršič, France (1981). "Gradivo za zgodovino Društva za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana" [Sources for the history of the Ljubljana Cave Exploration Society] (PDF). Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Vol. 11. Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. pp. 3–28. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ a b c "Zgodovina DZRJL / 1910-1918" [History of DZRJL / 1910-1918] (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Kranjc, Andrej (2018). "Brinšek, Bogomil (1884–1914)". Slovenska biografija (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Slovenska akademija znanosti in umetnosti, Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Kunaver, Pavel (1922). Kraški svet in njegovi pojavi [The Karst world and its phenomena] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Učiteljska tiskarna. p. 104.

- ^ a b "Zgodovina DZRJL / 1919-1940" [History of DZRJL / 1919-1940] (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Duckeck, Jochen (2006). "Županova Jama - Taborska Jama". Nürnberg, Germany: showcaves.com. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Kunaver, Pavel (1932). V prepadih [In the Precipices] (in Slovenian). Celje: Družba sv. Mohorja. p. 163.

- ^ Gorec, Sonja (1971). "Šerko, Alfred Sr. (1879–1938)". Slovenska biografija (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Slovenska akademija znanosti in umetnosti, Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d Mlinar, Ciril (1996). "Razvoj jamskega potapljanja v Sloveniji" [The development of cave diving in Slovenia] (PDF). Naše jame (in Slovenian). 38. Jamarska zveza Slovenije: 116–136. ISSN 0547-311X. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ Kranjc, Andrej (2017). "Bar, Franci (1901–1988)". Slovenska biografija (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Slovenska akademija znanosti in umetnosti, Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Zgodovina DZRJL / 1941-1960" [History of DZRJL / 1941-1960] (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. 2024. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ Šerko, Alfred; Michler, Ivan (1952). Postojnska jama in druge zanimivosti Krasa [Postojnska jama and other attractions of the Karst] (in Slovenian). Postojna: Turistično podjetje Kraške jame Slovenije. p. 166.

- ^ Seliškar, Albin (1948). "Dr. Alfred Šerko". Proteus (in Slovenian). 11 (2). Prirodoslovno društvo Slovenije: 33–35.

- ^ Jakopin, Primož (October 2023). "Miran Marussig, caver and road builder". Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ Kunaver, Jurij (1960). "Brezno pri Medvedovi konti na Pokljuki" [Brezno pri Medvedovi konti on Pokljuka Plateau] (PDF). Naše jame (in Slovenian). 2 (1–2). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Slovenije: 30–39. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ Gospodarič, Rado (1968). "Nekaj novih speleoloških raziskav v porečju Ljubljanice leta 1966" [New speleological exploration in the Ljubljanica river basin in 1966] (PDF). Naše jame (in Slovenian). 9. Društvo za raziskovanje jam Slovenije: 37–44. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ a b c "Zgodovina DZRJL / 1961-1974" [History of DZRJL / 1961-1974] (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. 2024. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ a b Šušteršič, France (1969). "Nove raziskave v Žankani jami pri Rašporju" [New exploration in Žankana jama near Rašpor] (PDF). Naše jame (in Slovenian). 11. Jamarska zveza Slovenije [Speleological Association of Slovenia]: 57–66. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ Glavaš, Ivan (2017). "Jama kod Rašpora – 95 godina istraživanja" [Jama kod Rašpora – 95 years of exploration]. Subterranea Croatica (in Croatian). 15 (1). Karlovac: Speleološki klub "Ursus spelaeus": 2–13. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ Battelini, Rodolfo (1926). Abisso Bertarelli nelle sue emozionanti e tragiche esplorazioni [Abisso Bertarelli in its exciting and tragic explorations] (PDF) (in Italian). Trieste: Commissione Grotte dell' "Alpina delle Giulie". p. 88. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ Medeot, Saverio L. (1974). Una tragedia speleologica di 50 anni fa: l'Abisso Bertarelli (1925–1975) [A speleological tragedy of 50 years ago: the Bertarelli Abyss (1925–1975)] (PDF) (in Italian). Trieste: Commissione Grotte Eugenio Boegan. p. 56. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "Storia del record mondiale di profondità in grotta dal 1839 al 2012" [History of the world record in cave depth from 1839 to 2012] (in Italian). CENS – Centro Escursionistico Naturalistico Speleologico. 26 January 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ Hribar, France (1959). "Najgloblja brezna v Jugoslaviji" [The deepest abysses in Yugoslavia] (PDF). Naše jame [Our Caves] (in Slovenian). 1. Jamarska zveza Slovenije [Speleological Association of Slovenia]: 29–29. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "DZRJL History: 1961 – 1974". DZRJL [Ljubljana Cave Exploration Society]. 23 August 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ Krivic, Primož (1970). "Gouffre Berger, Cuves de Sassenage". Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Vol. 2. Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. pp. 4–9. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Zgodovina DZRJL / 1975-1988" [History of DZRJL / 1975-1988] (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. 2024. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ a b Pirnat, Jože; Planina, Tomaž (1973). "Brezno pri gamsovi glavici v Julijskih Alpah" [The pothole "Brezno pri Gamsovi glavici" in Julian Alps] (PDF). Naše jame [Our Caves] (in Slovenian). 15: 47–55. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ Jakopin, Primož (6 January 2021). "Jurij Andjelić – Yeti / My caves are on Mt. Pršivec". Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ "Brezno pri gamsovi glavici, Kataster jam, kat. št. 3457" [Slovenian Cave Registry, Cave No. 3457] (in Slovenian and English). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Jakopin, Primož (1972), "O numeričnem vrednotenju kraških objektov" [Numerical Valuation of Objects on Karst], 6th Congress of Yugoslavia speleologists - Congress program and lecture summaries (in Slovenian), Ljubljana: Jamarska zveza Slovenije, pp. 41–42

- ^ Jakopin, Primož (22–27 June 1981). Macrostereological Evaluation of Cave Space. 3rd European symposium for stereology. Proceedings of the European Symposium for Stereology. Ljubljana: Stereological Section of the Yugoslavian Association of Anatomists / Jožef Stefan Institute / Edvard Kardelj University (published 1981). pp. 621–628. ISSN 0350-3062. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ Jakopin, Primož (18–24 July 1981). On Measuring Caves by Volume. 8th international congress of speleology. Bowling Green, KY: Department of Geology, Georgia Southwestern College, Americus (published 1981). pp. 270–272. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ Rojšek, Daniel (11–14 September 1987). "Natural Heritage of the Classical Karst (Kras)" (PDF). In Jurij Kunaver (ed.). Karst and Man: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Human Influence in Karst. International Symposium on Human Influence in Karst. Postojna: Department of Geography, Philosophical Faculty, Ljubljana University. pp. 255–265. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ a b Biščak, Luka (2018). "Plezanje v Martelovi dvorani na koncu kanjona Škocjanskih jam" [Climbing in the Martel Hall at the End of Škocjanske jame Cave Canyon]. Glasnik Občine Divača / Divača Municipality Herald (in Slovenian). No. 2. pp. 47–48. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Skoberne, Peter (March 1997). "In Memoriam Rado Smerdu (1949 - 1984)" (PDF). Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Vol. 2. Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. pp. 73–74. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ "Kanin treasures one tenth of world's deepest caves". STAscience. 22 November 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d Nenova, Milena (9 October 2020). "Interview #8 – Spela Borko, Slovenia". Cerovo, Bulgaria: Pod RB. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ a b Turk, Janez; Malard, Arnauld; Jeannin, Pierre-Yves; Petrič, Metka; Gabrovšek, Franci; Ravbar, Nataša; Vouillamoz, Jonathan; Slabe, Tadej; Sordet, Valentin (15 April 2015). "Hydrogeological characterization of groundwater storage and drainage in an alpine karst aquifer (the Kanin massif, Julian Alps)". Hydrological Processes. 29 (8). John Wiley & Sons: 1986–1998. ISSN 1099-1085. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ De Waele, Jo; Gutiérrez, Francisco (2022). Karst Hydrogeology, Geomorphology and Caves. John Wiley & Sons. p. 607.

- ^ a b "Zgodovina DZRJL / 1989-2000" [History of DZRJL / 1989-2000] (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. 2024. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ Simić, Marko (2002). "Izstop Društva za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana iz Jamarske zveze Slovenije" [Withdrawal of the Ljubljana Cave Exploration Society from the Speleological Association of Slovenia.]. Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. pp. 15–22. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Lajovic, Aleš (2024). "Petdeset let Jamarske zveze Slovenije" [Fifty years of the Speleological Association of Slovenia (JZS)] (in Slovenian). Jamarska zveza Slovenije. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ "Zgodovina DZRJL / 2001-2010" [History of DZRJL / 2001-2010] (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. 2024. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ Prelovšek, Mitja; Gabrovšek, Franci; Covington, Matt (2014). "Raziskave v Renetovem breznu 2011-2012" [Exploration in Renejevo brezno 2011-2012]. Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. pp. 8–12. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ Marušič, Franc (2014). "Brezno rumenega maka (P4)" (PDF). Jamar (in Slovenian). Vol. 11. Jamarska zveza Slovenije. p. 7. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ Di Batista, Matic (2016). "Sveži veter v Renejevem breznu" [Fresh wind in Renejevo brezno] (PDF). Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. pp. 22–25. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ Flis, Jaka (2016). "Brezno na Toscu ali Habičev pekel" [Brezno na Toscu or Habič's hell] (PDF). Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. p. 27. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ Borko, Špela (2018). "Brezno rumenega maka (P 4)" [The Abyss of the Yellow Poppy (P 4)] (PDF). Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. pp. 33–36. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Di Batista, Matic (2019). "Brezno na Toscu" (PDF). Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. pp. 30–33. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ Bevc, Jure (2019). "Raziskave v Romeu v letu 2018" [Exploration in Romeo in 2018] (PDF). Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. pp. 30–33. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ a b Di Batista, Matic (2020). "Odkritje leta: Planina Poljana" [Discovery of the year: Planina Poljana] (PDF). Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. pp. 16–19. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Borko, Špela; Bevc, Jure; Di Batista, Matic (24–31 July 2022). Hidden gem in the heart of karst exploration (PDF). 18th International Congress of Speleology. Proceedings - Vol. II - Caving and explorations. Savoie Mont Blanc: UIS. pp. 45–48. ISBN 978-2-7417-0692-2. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ a b c "eKataster Cave Database" (in Slovenian and English). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ a b Borko, Špela (November 2023). "Planina Poljana" (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ "Sistema Cheve 2019 Personnel". United States Deep Caving Team, Inc. 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "Najdaljše in najgloblje jame v Sloveniji" [The longest and deepest caves in Slovenia] (in Slovenian). Jamarska zveza Slovenije [Speleological Association of Slovenia]. 2024. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ "Zgodovina DZRJL / 2010-2020" [History of DZRJL / 2010-2020] (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Gabrovšek, Franci; Otoničar, Bojan (16–18 September 2010). Kras na kaninskih podih [Karst on Kanin plateau] (PDF). 3. Slovenski geološki kongres (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: ZRC SAZU. pp. 99–106. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ Borko, Špela (2021). "Sistem Renejevo brezno - P 4" [Renejevo brezno - P 4] (PDF). Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. pp. 27–29. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Di Batista Borko, Špela (2024). "Sistem Pokljuškega grebena" [Pokljuka ridge cave system] (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Di Batista, Matic (2022). "Pet akcij, -1081 metrov" [Five trips, -1081 meters] (PDF). Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. pp. 27–30. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ Jakopin, Primož (31 August 2021). "Boybuloq 2021 / Expedition to caves of the Chul-Bair mountain ridge in Uzbekistan". Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ Delić, Teo (2023). "Krivopeta jama - presenečenje na skrajnem zahodnem robu Slovenije" [Krivopeta jama - a surprise on the far western edge of Slovenia] (PDF). Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. pp. 16–20. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ Di Batista, Matic (2022). "Predsedniške novičke" [Presidential news] (PDF). Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. p. 2. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ Bevc, Jure (2023). "Brezno spečega dinozavra v 2022" [The Abyss of the Sleeping Dinosaur in 2022] (PDF). Glas podzemlja (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. pp. 47–49. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ Presetnik, Primož; Fajdiga, Bojana (2010). "Naši člani 1910-2010" [DZRJL members 1910-2010] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ "Dosedanji predsedniki DZRJL" [The presidents of DZRJL] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Bohinec, Valter (1959). "»Našim jamam« na pot" [A message to the journey of »Naše jame«] (PDF). Naše jame (in Slovenian). 1. Društvo za raziskovanje jam Slovenije: 1–4. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ "Glas podzemlja" (in Slovenian). Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Novak, Dušan (1965). "Jamarski priročnik" (PDF). Planinski vestnik (in Slovenian). Vol. 65, no. 7. Ljubljana: Planinska zveza Slovenije. pp. 328–329. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ Urankar, Rafko; Šušteršič, France; Simić, Marko; Praprotnik, Anton (2001). Ne hodi v jame brez glave [Don't go into caves without a head] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. p. 131. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ "Druge publikacije" [Other publications] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Društvo za raziskovanje jam Ljubljana. 2024. Retrieved 4 February 2024.