Lithuanian mythology

| Part of a series on |

| Baltic religion |

|---|

|

Lithuanian mythology (Lithuanian: Lietuvių mitologija) is the mythology of Lithuanian polytheism, the religion of pre-Christian Lithuanians. Like other Indo-Europeans, ancient Lithuanians maintained a polytheistic mythology and religious structure. In pre-Christian Lithuania, mythology was a part of polytheistic religion; after Christianisation mythology survived mostly in folklore, customs and festive rituals. Lithuanian mythology is very close to the mythology of other Baltic nations such as Prussians and Latvians, and is considered a part of Baltic mythology.

Sources and evidence

[edit]

Early Lithuanian religion and customs were based on oral tradition. Therefore, the very first records about Lithuanian mythology and beliefs were made by travellers, Christian missionaries, chronicle writers and historians. Original Lithuanian oral tradition partially survived in national ritual and festive songs and legends which started to be written down in the 18th century.

The first bits about Baltic religion were written down by Herodotus describing Neuri (Νευροί)[1] in his Histories and Tacitus in his Germania mentioned Aestii wearing boar figures and worshipping Mother of gods. Neuri were mentioned by Roman geographer Pomponius Mela. In the 9th century there is one attestation about Prussian (Aestii) funeral traditions by Wulfstan. In 11th century Adam of Bremen mentioned Prussians, living in Sambia and their holy groves. 12th century Muslim geographer al-Idrisi in The Book of Roger mentioned Balts as worshipers of Holy Fire and their flourishing city Madsun (Mdsūhn, Mrsunh, Marsūna).[2]

The first recorded Baltic myth - The Tale of Sovij was detected as the complementary insert in the copy of Chronographia (Χρονογραφία) of Greek chronicler from Antioch John Malalas rewritten in the year 1262 in Lithuania. It is a first recorded Baltic myth, also the first placed among myths of other nations – Greek, Roman and others. The Tale of Sovij describes the establishing of cremation custom which was common among Lithuanians and other Baltic nations. The names of the Baltic gods lt:Andajus, Perkūnas, lt:Žvorūna, and a smith-god lt:Teliavelis are mentioned.[3][4]

When the Prussian Crusade and Lithuanian Crusade started, more first-hand knowledge about beliefs of Balts were recorded, but these records were mixed with propaganda about "infidels". One of the first valuable sources is the Treaty of Christburg, 1249, between the pagan Prussian clans, represented by a papal legate, and the Teutonic Knights. In it worship of Kurkas (Curche), the god of harvest and grain, pagan priests (Tulissones vel Ligaschones), who performed certain rituals at funerals are mentioned.[5][page needed]

Chronicon terrae Prussiae is a major source for information on the Order's battles with Old Prussians and Lithuanians. It contains mentionings about Prussian religion and the center of Baltic religion – Romuva, where lives Kriwe-Kriwajto as a powerful priest who was held in high regard by the Prussians, Lithuanians, and Balts of Livonia.

The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, which covers the period 1180 – 1343, contains records about ethical codex of the Lithuanians and the Baltic people.

Descriptiones terrarum,[6] written by an anonymous author in the middle of 13th century. The author was a guest at coronation of Lithuanian king Mindaugas. The author also mentioned that Lithuanians, Yotwingians and Nalsenians embraced Christianity quite easily, since their childhood nuns were usually Christian, but Christianity in Samogitia was introduced only with a sword.

Die Littauischen Wegeberichte (The descriptions of Lithuanian routes) is a compilation of 100 routes into the western Grand Duchy of Lithuania prepared by the Teutonic Knights and their spies in 1384–1402. It contains descriptions and mentionings of Lithuanian holy groves and sacrificial places — alkas.

Hypatian Codex written in 1425, mentions Lithuanian gods and customs.

Simon Grunau was the author of Preussische Chronik, written sometime between 1517 and 1529. It became main source for research of Prussian mythology and one of the main sources of Lithuanian mythology researchers and reconstructors. It was the first source which described the flag of Vaidevutis. The book contained many questionable ideas, though.[which?]

French theologian and cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church, Pierre d'Ailly mentions the Sun (Saulė) as one of the most important Lithuanian gods, which rejuvenates the world as its spirit. Like Romans, Lithuanians consecrate the Sunday entirely for the Sun. Although they are worshipping the Sun, they have no temples. The astronomy of Lithuanians is based on the Moon calendar.[7]

Enea Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini, who later became the Pope Pius II, in the section de Europa of his book Historia rerum ubique gestarum, cited Jerome of Prague, who attested Lithuanians worshiping the Sun and the iron hammer which was used to free the Sun from the tower. He mentioned also Christian missionaries cutting off holy groves and oaks, which Lithuanians believed to be homes of the gods.[8]

Jan Łasicki created De diis Samagitarum caeterorumque Sarmatarum et falsorum Christianorum (Concerning the gods of Samagitians, and other Sarmatians and false Christians) - written c. 1582 and published in 1615, although it has some important facts it also contains many inaccuracies, as he did not know Lithuanian and relied on stories of others. The list of Lithuanian gods, provided by Jan Łasicki, is still considered an important and of interest for Lithuanian mythology. Later researchers Teodor Narbutt, Simonas Daukantas and Jonas Basanavičius relied on his work.

Matthäus Prätorius in his two-volume Deliciae Prussicae oder Preussische Schaubühne, written in 1690, collected facts about Prussian and Lithuanian rituals. He idealised the culture of Prussians, considered it belonging to the culture of the Antique world.

The Sudovian Book was an anonymous work about the customs, religion, and daily life of the Prussians from Sambia (Semba). The manuscript was written in German in the 16th century. The book included a list of Prussian gods, sorted in a generally descending order from sky to earth to underworld and was and important source for reconstructing Baltic and Lithuanian mythology.

Further sources

[edit]The Pomesanian statute book of 1340, the earliest attested document of the customary law of the Balts, as well as the works of Dietrich of Nieheim (Cronica) and Sebastian Münster (Cosmographia).

Lithuanian song collections recorded by Liudvikas Rėza, Antanas Juška and many others in 19th century and later - among them mythological and ritual songs. For example, the song recorded by L. Rėza - Mėnuo saulužę vedė (Moon Married the Sun) reflects beliefs that L. Rėza stated were still alive at the moment of recording.[9]

Folklore collections by, among others, Mečislovas Davainis-Silvestraitis (collected about 700 Samogitian fairy-tales and tales (sakmės)) and Jonas Basanavičius (collected hundreds of songs, tales, melodies and riddles).

History of scholarship

[edit]

Surviving information about Baltic mythology in general is fragmented. As with most ancient Indo-European cultures (e.g. Greece and India), the original primary mode of transmission of seminal information such as myths, stories, and customs was oral, the then-unnecessary custom of writing being introduced later during the period of the text-based culture of Christianity. Most of the early written accounts are very brief and made by foreigners, usually Christians, who disapproved of pagan traditions. Some academics regard some texts as inaccurate misunderstandings or even fabrications. In addition, many sources list many different names and different spellings, thus sometimes it is not clear if they are referring to the same thing.

Lithuania became Christianized between the end of the 14th century and the beginning of the 15th century, but Lithuanian polytheism survived for another two centuries, gradually losing influence and coherence as a religion. The last conceptions of the old religion survived approximately until the beginning of the 19th century. The relics of the old polytheistic religion were already interwoven with songs, tales and other mythic stories. Gradually Lithuanian polytheism customs and songs merged with the Christian tradition. In the beginning of the 20th century Michał Pius Römer noted - "Lithuanian folklore culture having its sources in heathenism is in complete concord with Christianity".[10]

In 1883, Edmund Veckenstedt published a book Die Mythen, Sagen und Legenden der Zamaiten (Litauer) (English: The myths, sagas and legends of the Samogitians (Lithuanians)).[11]

It is not easy to reconstruct Lithuanian mythology in its full form. Lithuanian mythology was not static, but constantly developed, so it did not remain in the same form over the longer periods.

J. Dlugosz tried to research myths and religion of ancient Lithuanians. He considered it close to the ancient culture of Rome. Almost all authors of Renaissance - J. Dlugosz, M. Stryjkowski, J. Lasicki, M. Prätorius and others, relied not only on previous authors and chroniclers, but included facts and attestations of their time as well.[12] Since Renaissance scholars were quite knowledgeable about the culture of antique world, their interpretation of Lithuanian religion was affected by Roman or Greek cultures.

Many scholars preferred to write their own reconstructions of Lithuanian mythology, based also on historical, archaeological, and ethnographic data. The first such reconstruction was written by the Lithuanian historian Theodor Narbutt at the beginning of the 19th century.

The interest in Baltic and Lithuanian mythology was growing along with interest in Lithuanian language among Indo-Europeanists, since the conservative and native Baltic nations preserved very archaic language and cultural traditions.[13][14]

Italian linguist Vittore Pisani along with his research of Baltic languages, studied Lithuanian mythology. Two well-known attempts at reconstruction have been attempted more recently by Marija Gimbutas and Algirdas Julien Greimas. According to G. Beresenevičius it is impossible to reconstruct the Lithuanian mythology in entirety, since there were only fragments which survived. Marija Gimbutas explored Lithuanian and Baltic mythology using her method - archaeomythology where archeological findings being interpreted through known mythology. A material related to the Lithuanian spells was used by V. Ivanov and V. Toporov to restore the Indo-European myths.[15]

The most modern academics exploring Lithuanian mythology in the second half of the 20th century were Norbertas Vėlius and Gintaras Beresnevičius.[12]

Pantheon of Lithuanian gods

[edit]

The pantheon of Lithuania was formed during thousands of years by merging pre-Indo-European and Indo-European traditions. Feminine gods such as Žemyna (goddess of the earth) are attributed to pre-Indo-European tradition,[16] whereas very expressive thunder-god Perkūnas is considered to derive from Indo-European religion. The hierarchy of the gods depended also on social strata of ancient Lithuanian society.[17]

Dievas, also called Dievas senelis ('old man God'), Dangaus Dievas ('the God of heaven') - the supreme sky god. It is descended from Proto-Indo-European *deiwos, "celestial" or "shining", from the same root as *Dyēus, the reconstructed chief god of the Proto-Indo-European pantheon. It relates to ancient Greek Zeus (Ζευς or Δίας), Latin Dius Fidius,[18] Luvian Tiwat, German Tiwaz. The name Dievas is being used in Christianity as the name of God.

Andajus (Andajas, Andojas) was mentioned in chronicles as the most powerful and highest god of Lithuanians. Lithuanians cried its name in a battle. It might just be an epithet of the supreme god - Dievas.[19]

Perkūnas, god of thunder, also synonymically called Dundulis, Bruzgulis, Dievaitis, Grumutis etc. It closely relates to other thunder gods in many Indo-European mythologies: Vedic Parjanya, Celtic Taranis, Germanic Thor, Slavic Perun. The Finnic and Mordvin/Erza thunder god named Pur'ginepaz shows in folklore themes that resemble the imagery of Lithuanian Perkunas.[20][21] Perkūnas is the assistant and executor of Dievas's will. He is also associated with the oak tree.[22][23]

Dievo sūneliai (the "sons of Dievas") – Ašvieniai, pulling the carriage of Saulė (the Sun) through the sky.[24][25] Like the Greek Dioscuri Castor and Pollux, it is a mytheme of the Divine twins common to the Indo-European mythology. Two well-accepted descendants of the Divine Twins, the Vedic Aśvins and the Lithuanian Ašvieniai, are linguistic cognates ultimately deriving from the Proto-Indo-European word for the horse, *h₁éḱwos. They are related to Sanskrit áśva and Avestan aspā (from Indo-Iranian *aćua), and to Old Lithuanian ašva, all sharing the meaning of "mare".[26][27]

Velnias (Velas, Velinas) – chthonic god of the underworld, related to the cult of dead.[28] The root of the word is the same as of Lithuanian: vėlė ('soul of the deceased'). After the introduction of Christianity it was equated with evil and Velnias became a Lithuanian name for devil. In some tales, Velnias (the devil) was the first owner of fire. God sent a swallow, which managed to steal the fire.[29]

Žemyna (Žemė, Žemelė) (from Lithuanian: žemė 'earth') is the goddess of the earth. It relates to Thracian Zemele (mother earth), Greek Semelē (Σεμέλη).[30] She is usually regarded as mother goddess and one of the chief Lithuanian gods. Žemyna personifies the fertile earth and nourishes all life on earth, human, plant, and animal. The goddess is said to be married to either Perkūnas (thunder god) or Praamžius (manifestation of chief heavenly god Dievas). Thus the couple formed the typical Indo-European pair of mother-earth and father-sky. It was believed that in each spring the earth needs to be impregnated by Perkūnas - the heavens rain and thunder. Perkūnas unlocks (atrakina) the Earth. It was prohibited to plow or sow before the first thunder as the earth would be barren.[31]

Žvėrinė (Žvorūna, Žvorūnė) – is the goddess of hunting and forest animals. Medeina is the name in other sources.[32]

Medeina – the goddess of forest and hunting. Researchers suggests that she and Žvėrinė (Žvorūnė) could have been worshipped as the same goddess.[33]

Žemėpatis (from Lithuanian: žemė 'earth' and Lithuanian: pàts 'autonomous decision maker, ruler'; or 'Earth Spouse'[34]) – god of the land, harvest, property and homestead.[35] Martynas Mažvydas in 1547 in his Catechism urged to abandon cult of Žemėpatis.[36][37][38]

Žvaigždikis (Žvaigždystis, Žvaigždukas, Švaistikas) – the god of the stars, powerful god of light, who provided light for the crops, grass and the animals. It was also known as Svaikstikas (Suaxtix, Swayxtix, Schwayxtix, Schwaytestix) by Yotvingians.[39]

Gabija (also known as Gabieta, Gabeta, Matergabija, Pelengabija) is the spirit or goddess of the fire.[40] She is the protector of family fireplace (šeimos židinys) and family. Her name is derived from Lithuanian: gaubti – to cover, to protect. Nobody was allowed to step on firewood, since it was considered a food for the fire goddess. Even today there is a tradition of weddings in Lithuania to light a new symbolic family fireplace from the parents of the newlyweds.[41]

Laima (from Lithuanian: lemti – 'to destine') or Laimė – is the destiny-giver goddess.[42][43]

Bangpūtys (from Lithuanian: banga 'wave' and Lithuanian: pūsti 'to blow' ) – god of the sea, wind, waves and storm.[44] Was worshipped by fishermen and seamen.[45][46]

Teliavelis/Kalevelis – a smith-god or the god of roads.[47] First mentioned in a 1262 copy of Chronographia (Χρονογραφία) of John Malalas as Teliavel. Lithuanian linguist Kazimieras Būga reconstructed a previous form – Kalvelis (from Lithuanian: kalvis 'a smith' in diminutive form).[48] Teliavelis/Kalevelis freed Saulė (Sun) from the dark using his iron hammer. In Lithuanian fairy-tales recorded much later, there is very frequent opposition of kalvis ('smith') and velnias ('devil').

The periods of Lithuanian mythology and religion

[edit]

Pre-Christian Lithuanian mythology is known mainly through attested fragments recorded by chroniclers and folks songs; the existence of some mythological elements, known from later sources, has been confirmed by archaeological findings. The system of polytheistic beliefs is reflected in Lithuanian tales, such as Jūratė and Kastytis, Eglė the Queen of Serpents and the Myth of Sovij.

The next period of Lithuanian mythology started in the 15th century, and lasted until approximately the middle of the 17th century. The myths of this period are mostly heroic, concerning the founding of the state of Lithuania. Perhaps two the best known stories are those of the dream of the Grand Duke Gediminas and the founding of Vilnius,[49] the capital of Lithuania, and of Šventaragis' Valley, which also concerns the history of Vilnius. Many stories of this kind reflect actual historical events. Already by the 16th century, there existed a non-unified pantheon; data from different sources did not correspond one with another, and local spirits, especially those of the economic field, became mixed up with more general gods and ascended to the level of gods.[50]

The third period began with the growing influence of Christianity and the activity of the Jesuits, roughly since the end of the 16th century. The earlier confrontational approach to the pre-Christian Lithuanian heritage among common people was abandoned, and attempts were made to use popular beliefs in missionary activities. This also led to the inclusion of Christian elements in mythic stories.

The last period of Lithuanian mythology began in the 19th century, when the importance of the old cultural heritage was admitted, not only by the upper classes, but by the nation more widely. The mythical stories of this period are mostly reflections of the earlier myths, considered not as being true, but as the encoded experiences of the past.

Elements and nature in the Lithuanian mythology

[edit]Elements, celestial bodies and nature phenomena

[edit]

Stories, songs, and legends of this kind describe laws of nature and such natural processes as the change of seasons of the year, their connections with each other and with the existence of human beings. Nature is often described in terms of the human family; in one central example (found in many songs and stories), the sun is called the mother, the moon the father, and stars the sisters of human beings. Lithuanian mythology is rich in gods and minor gods of water, sky and earth. Holy groves were worshipped, especially beautiful and distinctive places – alka were selected for sacrifices for gods.

Fire

[edit]

Fire is very often mentioned by chroniclers, when they were describing Lithuanian rituals. The Lithuanian king Algirdas was even addressed as a "fire worshiper King of Lithuania" (τῷ πυρσολάτρῃ ῥηγὶ τῶν Λιτβῶν) in the documents of a patriarch Nilus of Constantinople.[51]

Water

[edit]Water was considered a primary element - legends describing the creation of the world, usually state that "at first there was nothing but water".[52] Springs were worshiped - they were considered holy. The river was seen as separating the areas of alive and death. If the settlement was placed at the river, then the deceased were buried in another side of the river. Water sources were highly respected and was tradition to keep any water - spring, well, river, lake clean. Cleanliness was associated with holiness.

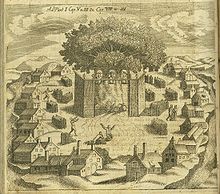

Holy groves

[edit]Holy groves were considered not holy in itself, but as a home of gods.[53] Jerome of Prague was an ardent missionary in Lithuania, leading the chopping of the holy groves and desecration of Lithuanian sacred heathen places. Lithuanian woman reached Vytautas the Great with plaints that they are losing their places of Dievas, the places where they prayed supreme god – Dievas to withhold the Sun or rain.[54] Now, when the holy groves are destroyed they do not know where to search for Dievas since it lost its home. Jerome of Prague was finally sent out of the country.

Celestial bodies

[edit]Celestial bodies – planets were seen as a family. Mėnulis (Moon) married Saulė (Sun) and they had seven daughters: Aušrinė (Morning Star – Venus), Vakarinė (Evening Star – Venus), Indraja (Jupiter), Vaivora or son Pažarinis in some versions (Mercury), Žiezdrė (Mars), Sėlija (Saturn), Žemė (Earth). Three daughters lived close to their mother Saulė, another three were traveling.[55]

Grįžulo Ratai (also – Grigo Ratai, Perkūno Ratai, Vežimas) (Ursa Major) was imagined as a carriage for the Sun which was travelling through the sky, Mažieji Grįžulo Ratai (Ursa Minor) – a carriage for the daughter of Sun.[56]

Zodiac or Astrological signs were known as liberators of the Saulė (Sun) from the tower in which it was locked by the powerful king – the legend recorded by Jerome of Prague in 14-15th century.[50]: 226

Lithuanian legends

[edit]Legends (padavimai, sakmės) are a short stories explaining the local names, appearance of the lakes and rivers, other notable places like mounds or big stones.[57]

Lithuanian myths

[edit]- The Tale of Sovij[3]

- The myth of god-smith Teliavelis freeing the Sun

- The cosmogonic myths of celestial bodies: Aušrinė, Saulė and Mėnulis, Grįžulo Ratai - also known as "the celestial marriage drama".[58]

- The nine-point deer (Elnias devyniaragis) – the deer which carries the sky with planets on its antler.

- Eglė the Queen of Serpents

- Jūratė and Kastytis

- The Tale of priestess (vaidilutė) Birutė and Grand Duke Kęstutis.

- Iron Wolf – the legend about founding of Vilnius.

- Palemonids – the legend of origin of Lithuanians.

Legacy

[edit]Lithuanian mythology serves as a constant inspiration for Lithuanian artists. Many interpretations of Eglė – the Queen of Serpents were made in poetry and visual art. In modern Lithuanian music polytheistic rituals and sutartinės songs were source of inspiration for Bronius Kutavičius. Old Lithuanian names, related to nature and mythology are often given to the children. Many pagan traditions slightly transformed were adopted by the Christian religion in Lithuania. Oaks are still considered a special tree, and grass snakes are treated with care. Old songs and pagan culture serve as inspiration for rock and pop musicians.[59]

- Legacy of the Lithuanian mythology

-

Lithuanian type of cross - saulutė (little sun) containing ancient, pre-Christian motifs.

-

Parade belt of an officer of the Lithuanian Army, decorated with Žaltys ornaments.

-

Iron Wolf is used as a mascot by the Lithuanian military (the Motorised Infantry Brigade Iron Wolf)

-

Sculpture of Eglė the Queen of Serpents in Palanga, Lithuania

-

Sodas (Garden) - symbolic representation of the world and harmony.

See also

[edit] Lithuania portal

Lithuania portal Myths portal

Myths portal- Proto-Indo-European mythology

- Indo-European cosmogony

- Alka (Baltic religion)

- Baltic mythology

- Prussian mythology

- Latvian mythology

- Romuva (religion)

- Lizdeika

References

[edit]- ^ Matthews, W. K. (1948). "Baltic origins". Revue des Études Slaves. 24: 48–59. doi:10.3406/slave.1948.1468. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Senvaitytė, Dalia (2005). "Istorinių šaltinių informacija apie ugnį ir su ja susijusius ritualus". Ugnis senojoje lietuvių tradicijoje. Mitologinis spektas (PDF) (in Lithuanian). Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas. p. 7. ISBN 9955-12-072-X. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ a b Lemeškin 2009, p. 325.

- ^ Walter, Philippe (2011). "Archaeologia Baltica 15:The Ditty of Sovijus (1261).The Nine Spleens of the Marvelous Boar: An Indo-European Approach to a Lithuanian Myth". academia.edu. Klaipėda University Press. p. 72. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ Vėlius, Norbertas (1996). "Baltų religijos ir mitologijos šaltiniai" (PDF). tautosmenta.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "Descriptiones terrarum" (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ "Teliavelis – saulės kalvis" (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "Požalgirinė Lietuva Europos akimis" (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "Mitologinės dainos" (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Römeris, Mykolas (2020). Lietuva: Studija apie lietuvių tautos atgimimą (in Lithuanian) (2 ed.). Vilnius: Flavija. p. 19. ISBN 978-9955-844-04-4.

- ^ Veckenstedt, Edmund (1883). Die Mythen, Sagen und Legenden der Zamaiten (in German). Heidelberg: C. Winter. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Lietuvių mitologija". vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Puhvel 2001, p. 34.

- ^ Zaroff, Roman (2019). "Some aspects of pre-Christian Baltic religion". In Lajoye, Patrice (ed.). New Researches on the Religion and Mythology of the Pagan Slavs. Paris: Lingva. pp. 183–219. ISBN 979-10-94441-46-6.

- ^ Zavjalova, Marija. "Lithuanian Spells". lnkc.lt. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ Gimbutas, Marija; Miriam Robbins Dexter (1999). The Living Goddesses. University of California Press. pp. 199, 208-209. ISBN 0-520-22915-0.

- ^ Rowell, Stephen Christopher (2014). "Political Ramifications of The Pagan Cult". Lithuania Ascending: A Pagan Empire within East-Central Europe, 1295-1345. Cambridge University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-107-65876-9.

- ^ Puhvel 2001, p. 199.

- ^ Beresnevičius, Gintaras. "Andajas". Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Yurtov, A. 1883. Obraztsy mordovskoi narodnoi slovesnosti. 2nd ed. Kazan. p 129.

- ^ Jakov, O. 1848. O mordvakh, nakhodiashchikhsia v Nizhegorodskom uezde Nizhegorodskoi gubernii. Saint Petersburg. p 59–60.

- ^ "Perkūnas". Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Klimka, Libertas (2011). "Medžių mitologizavimas tradicinėje lietuvių kultūroje" (PDF). Acta humanitarica universitatis Saulensis (in Lithuanian). 13: 22–25. ISSN 1822-7309. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ West 2007, p. 189.

- ^ Parpola 2015, p. 109.

- ^ Derksen, Rick (2015). Etymological Dictionary of the Baltic Inherited Lexicon. Brill. p. 65. ISBN 978-90-04-27898-1.

- ^ Lubotsky, Alexander. "Indo-Aryan Inherited Lexicon". Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Project. Leiden University. See entry áśva- (online database).

- ^ "Velnias". Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Skabeikytė-Kazlauskienė, Gražina (2013). "Lithuanian Narrative Folklore" (PDF). esparama.lt. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University. p. 80.

- ^ Dundulienė 2018, p. 111.

- ^ Dundulienė 2018, p. 112.

- ^ "Žvorūnė". Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ "Medeina". Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Borissoff, Constantine L. (2014). “Non-Iranian Origin of the Eastern-Slavonic God Xŭrsŭ/Xors" [Neiranskoe proishoždenie vostočnoslavjanskogo Boga Hrsa/Horsa]. In: Studia Mythologica Slavica 17 (October). Ljubljana, Slovenija. p. 22. https://doi.org/10.3986/sms.v17i0.1491.

- ^ Doniger, Wendy. Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. 1999. p. 1161. ISBN 0-87779-044-2

- ^ "Žemėpatis". Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Laurinkienė, Nijolė (2008). "Lietuvių žemės deivės vardai" [The Lithuanian names of the Goddess of the Earth]. In: Tautosakos darbai, XXXVI, pp. 77-78. ISSN 1392-2831

- ^ Eckert, Rainer (1999). “Eine Slawische Une Baltische Erdgottheit". Studia Mythologica Slavica 2 (May/1999). Ljubljana, Slovenija. pp. 214, 217. https://doi.org/10.3986/sms.v2i0.1850.

- ^ Beresnevičius, Gintaras; Vaitkevičienė, Daiva. "Svaistikas". mle.lt. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ "Gabija". Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Gimbutas, Marija; Miriam Robbins Dexter (1999). The Living Goddesses. University of California Press. p. 203. ISBN 0-520-22915-0.

- ^ "Laima". Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ "Laimė". Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ "Bangputys". Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Elertas, Dainius (2010). "Bangpūčio mitologema baltų pasaulėžiūroje" (PDF). Muziejininkų darbai ir įvykių kronika (in Lithuanian). 1. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Trinkūnas, Jonas; Ūsaitytė, Jurgita. "Bangpūtis - MLE". mle.lt. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ "Teliavelis". Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Greimas, Algirdas Julius (2005). Lietuvių mitologijos studijos (in Lithuanian). Baltos lankos. p. 388. ISBN 9955-584-78-5.

- ^ "Legend of Founding of Vilnius". Archived from the original on 20 October 2007.

- ^ a b Beresnevičius, Gintaras (2019). Lietuvių religija ir mitologija (in Lithuanian). Tyto Alba. ISBN 978-609-466-419-9.

- ^ Norkus, Zenonas (28 July 2017). An Unproclaimed Empire: The Grand Duchy of Lithuania: From the Viewpoint of Comparative Historical Sociology of Empires (1 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1138281547.

- ^ Beresnevičius, Gintaras. "Lithuanian Religion and Mythology". viduramziu.istorija.net. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Vaitkevičius, Vykintas. "The Sacred Groves of the Balts: Lost History and Modern Research". academia.edu. folklore.ee. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ Laurinkienė, Nijolė (2019). "Tarpininkai tarp žemės ir dangaus". Dangus baltų mitiniame pasaulėvaizdyje (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvių litearatūros ir tautosakos institutas. p. 27. ISBN 978-609-425-262-4.

- ^ "Dangus baltų gyvenime". apiebaltus.weebly.com (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Davainis-Silvestraitis, Mečislovas (1973). Pasakos sakmės oracijos (PDF) (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos ir literatūros institutas. p. 161. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ "Legends of Lithuania". kaunolegenda.lt. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Laurinkienė, Nijolė. "Dangiškųjų vestuvių mitas" [Myth of the celestial wedding]. In: Liaudies kultūra Nr. 5 (2018). pp. 25-33.

- ^ Strmiska, Michael. "Paganism-Inspired Folk Music, Folk Music-Inspired Paganism, and New Cultural Fusions in Lithuania and Latvia". Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production: 349. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Parpola, Asko (2015). The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization. Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 9780190226923.

- West, Morris L. (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199280759.

- Puhvel, Jaan (2001). Lyginamoji mitologija (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvių literatūros ir tautosakos institutas. ISBN 9986-513-98-7.

- Dundulienė, Pranė (2018). Pagonybė Lietuvoje. Moteriškosios dievybės (in Lithuanian) (3 ed.). Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras. ISBN 978-5-420-01638-1.

- Lemeškin, Ilja (2009). Sovijaus sakmė ir 1262 metų chronografas (Myth of Sovius and the Chronograph of 1262) (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvos literatūros ir tautosakos institutas. ISBN 978-609-425-008-8. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- Murray, Alan V., ed. (5 December 2016). The Clash of Cultures on the Medieval Baltic Frontier. Routledge. ISBN 978-0754664833.

Further reading

[edit]On mythology:

- Rimantas Balsys. Paganism of Lithuanians and Prussians (2020). Klaipėda, Klaipėdos universiteto leidykla. ISBN 9786094810749

- Darius Baronas. Christians in Late Pagan, and Pagans in Early Christian Lithuania: the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. Lithuanian Historical Studies. Vilnius : Lietuvos istorijos institutas. 2014, Vol. 19, p. 51-81 ISSN 1392-2343

- (in English) Marta Eva Betakova, Vaclav Blazek, Hana Betakova. Lexicon of Baltic Mythology. Universitaetsverlag Winter, 2021. ISBN 9783825348663.

- (in Lithuanian) Kazimieras Būga. "Medžiaga lietuvių, latvių ir prūsų mitologijai". Vilnius: M.Kuktos spaustuvė, 1909.

- Manvydas Vitkūnas, Gintautas Zabiela. Baltic hillforts: unknown heritage. Vilnius: Society of the Lithuanian Archaeology, 2017, 88 p. ISBN 9786099590028

- Vaida Kamuntavičienė (2015). "The Religious Faiths of Ruthenians and Old Lithuanians in the 17th Century According to the Records of the Catholic Church Visitations of the Vilnius Diocese". In: Journal of Baltic Studies 46:2, pp. 157–170. DOI: 10.1080/01629778.2015.1029956

- (in Lithuanian) Norbertas Vėlius. Mitinės lietuvių sakmių būtybės (1977) OCLC 186317016

- (in Lithuanian) Norbertas Vėlius. Laumių dovanos (1979) OCLC 5799779 (translated into English as Lithuanian mythological tales in 1998)

- (in Lithuanian) Norbertas Vėlius. Senovės baltų pasaulėžiūra (1983) OCLC 10021017 (translated into English as The World Outlook of the Ancient Balts in 1989, ISBN 978-5417000270)

- (in Lithuanian) Norbertas Vėlius. Chtoniškasis lietuvių mitologijos pasaulis (1987) OCLC 18359555

- (in Lithuanian) Norbertas Vėlius. Baltų religijos ir mitologijos šaltiniai (Sources of Baltic religion and mythology), 4 volumes. Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras: 1996–2005, Vilnius. ISBN 5-420-01518-8

- (in Lithuanian) Marija Gimbutas. Baltai priešistoriniais laikais: etnogenezė, materialinė kultūra ir mitologija. Vilnius: "Mokslas", 1985.

- (in Lithuanian) Gintaras Beresenevičius. Trumpas lietuvių ir prūsų religijos žodynas. Vilnius: Aidai, 2001. ISBN 9789955445319

- (in Lithuanian) Marija Gimbutas. Baltų mitologija: senovės lietuvių deivės ir dievai. Vilnius: Lietuvos Rašytojų sąjungos leidykla, 2002. ISBN 9789986392118

- (in Lithuanian) Jonas Basanavičius. Fragmenta mithologiae: Perkūnas - Velnias" (1887 m.; BsFM)

- (in Lithuanian) Jonas Basanavičius. Iš senovės lietuvių mitologijos (1926 m.; 9)

- (in Lithuanian) Lietuvių mitologija: iš Norberto Vėliaus palikimo (Lithuanian mythology. From the legacy of Norbertas Vėlius), 3 volumes. Mintis: 2013 ISBN 9785417010699

- Arūnas Vaicekauskas, Ancient Lithuanian calendar festivals, 2014, Vytautas Magnus University, Versus Aureus. ISBN 978-609-467-018-3,ISBN 978-609-467-017-6

- (in Lithuanian) Rimantas Balsys. Lietuvių ir prūsų pagonybė: alkai, žyniai, stabai. Klaipėdos universiteto leidykla: 2015, Klaipėda. ISBN 9789955188513

- (in Lithuanian) Rimantas Balsys. Lietuvių ir prūsų religinė elgsena: aukojimai, draudimai, teofanijos. Klaipėdos universiteto leidykla: 2017, Klaipėda. ISBN 978-9955-18-928-2

- (in Lithuanian) Gintaras Beresnevičius. Lietuvių religija ir mitologija (Lithuanian religion and mythology). Tyto Alba: 2019, Vilnius. ISBN 978-609-466-419-9

- (in Lithuanian) Rolandas Kregždys. Baltų mitologemų etimologijos žodynas I: Kristburgo sutartis (Etymological Dictionary of Baltic Mythologemes I: Christburg Treaty). Lietuvos kultūros tyrimų institutas: 2012, Vilnius. ISBN 978-9955-868-50-7

- (in Lithuanian) Rolandas Kregždys. Baltų mitologemų etimologijos žodynas II: Sūduvių knygelė (Etymological Dictionary of Baltic Mythologemes II: Yatvigian Book). Lietuvos kultūros tyrimų institutas: 2020, Vilnius. ISBN 978-609-8231-18-2

- (in Lithuanian) Nijolė Laurinkienė. Dangus baltų mitiniame pasaulėvaizdyje (The Concept of the Sky in the Baltic Mythical Worldview). Lietuvos literatūros ir tautosakos institutas: 2009, Vilnius. ISBN 978-609-425-262-4

- (in Lithuanian) Nijolė Laurinkienė. Senovės lietuvių dievas Perkūnas (Perkūnas - The God of Ancient Lithuanians). Lietuvos literatūros ir tautosakos institutas: 1996, Vilnius. ISBN 9986-513-14-6

- (in Lithuanian) Compiler Adomas Butrimas (2009). "Baltų menas / Art of the Balts“. Vilnius : Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla. ISBN 978-9955-854-36-4

- (in Lithuanian) Daiva Vaitkevičienė (2008). "Lietuvių užkalbėjimai: gydymo formulės / Lithuanian Verbal Healing Charms“. Lietuvos literatūros ir tautosakos institutas: 2009, Vilnius. ISBN 978-9955-698-94-4

- (in German) Adalbert Bezzenberger: Litauische Forschungen. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Sprache und des Volkstums der Litauer. Peppmüller, Göttingen 1882.

- (in German) August Schleicher: Lituanica. Abhandlungen der Wiener Akademie, Wien 1854. (über litauische Mythologie)

- (in German) Edmund Veckenstedt (Hrsg.): Mythen, Sagen und Legenden der Zamaiten (Litauer). Heidelberg 1883 (2 Bde.).

- (in German) Eduards Šturms. Die Alkstätten in Litauen, Baltic University, 1946.

- Razauskas, Dainius (2014). Visi dievai: "panteono" sąvokos kilmė, pirminis turinys ir lietuviškas atitikmuo ["All gods": the origin of the concept of pantheon and its Lithuanian counterpart "Visi dievai"]. Sovijaus studijų ir monografijų serija (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvos kultūros tyrimų institutas. ISBN 9789955868828.

On folktales:

- "Devyniabrolė: A folk tale". In: LITUANUS Winter 1961 - Vol 7 - No 4. pp. 103–104.

- Kaupas, Julius. "An Interpretation of Devyniabrolė". In: LITUANUS Winter 1961 - Vol 7 - No 4. pp. 105–108.

External links

[edit]- Gintaras Beresnevičius On periodisation and Gods in Lithuanian mythology.[1]

- Algirdas Julius Greimas, "Of Gods and Men: Studies in Lithuanian Mythology", Indiana Univ. Pr. (November 1992). ISBN 978-0253326522

- List of Lithuanian Gods Found in Maciej Sryjkowski chronicle by Gintaras Beresnevičius

- Lithuanian Religion and Mythology by Gintaras Beresnevičius.

- Cosmology Of The Ancient Balts by Limbertas Klimka and Vytautas Straižys.

- Book Mitología General (in Spanish) by Félix Guirand and Pedro Pericay with a chapter dedicated to Lithuanian mythology (Mitología lituana).