Lex Claudia de nave senatoris

| Lex Claudia | |

|---|---|

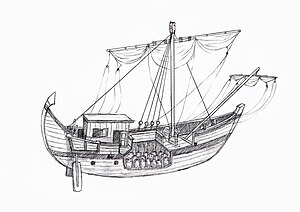

A Roman trade ship carrying amphorae. | |

| Quintus Claudius | |

| |

| Enacted by | Quintus Claudius |

| Enacted | 218 BC |

The lex Claudia (Classical Latin: [ɫeːks ˈkɫau̯di.a]) also known as the plebiscitum Claudianum[1] or the lex Claudia de nave senatoris,[2] was a Roman law passed in 218 BC. Proposed at the start of the Second Punic War, the law prohibited senators and their sons from owning an "ocean-going ship" (maritimam navem)[3] which had a capacity of more than 300 amphorae. It was proposed by the tribune Quintus Claudius and supported by a senator Gaius Flaminius (consul 223 BC and 217 BC). There are no surviving contemporary sources for the law; the only ancient source to explicitly discuss it being the historian Livy.[4] While Cicero (consul 63 BC) does mention the law in his prosecution of Verres in 70 BC,[5] this is only an indirect reference. As such, the ancient evidence is limited and only dates from nearly two centuries later. Nonetheless, modern scholarship has continued to debate the purpose and significance of the lex Claudia.

Historical context

[edit]

Third Century naval expansion

[edit]After Rome's expansion during the First Punic War (263–241 BC), Roman imperialism around the Mediterranean Sea saw the beginnings of economic exploitations of newly formed provinces. This naval activity increased throughout the third century.[6] The passage of the lex Claudia, designed to restrict shipping, is indicative of this increased naval activity.[7] For if there was no naval merchant activity, there would have been no need for such a law. The development of coinage and credit systems as well as the advancement in communication through roads, rivers and harbours, meant that long-distance trade became a significant aspect of the empire's economy.[8] Imported goods included food, slaves, metals and luxury goods, while exports consisted largely of pottery, gold and silver.[9] Rome's commercial interests were further expanded after Sicily and Sardinia become a province at the end of the First Punic War.[10] Commercial ships were expensive and costly to maintain, meaning that only members of the upper classes (senators and equestrians) were able to invest in long-distance shipping. However, little is definitively known concerning the exact circumstances that led to the creation of the lex Claudia.[11]

Second Punic War influence

[edit]Although the law was proposed at the start of the Second Punic War, it is difficult to say what impact this new war would have had, if any, on the passage of the law. After all, the Romans were nearly always at war during the third century BC. However, it is of course possible that the advent of the new war made an impact. The lex Claudia's ulterior purpose might have been to secure private ships for use in the war.[12] The targeted ships were probably large enough to carry the troops and supplies needed for warfare. If so, the law would then serve to aid the equestrians' merchant ambitions, limit the influence of senators and provide commanders with ships large enough to carry troops and supplies.

Conflict of the Orders

[edit]The third century BC may have also seen the resurgence of conflicts between the patrician and the plebeian classes. When the Roman Republic (res publica) was founded in 509 BC, it attempted to readjust the balance of power in favour of the people. However, the patrician class, made up of elite families, quickly began to dominate the political scene at the expense of the majority, the plebeians. The conflicts between the patricians and plebeians came to be known as the Conflict of the Orders. By 290 BC these conflicts largely came to an end when plebeian consuls were introduced. However, patrician/plebeian issues still surfaced from time-to-time in the later Republic. Although the most well-documented example of this conflict arose around the Gracchi (133/123 BC), it is possible that the passage of the lex Claudia may also be an example of this continuing theme.

Proposed by a tribune of the plebs and aimed at senators, the lex Claudia may be seen as an example of the plebeian order struggling to get ahead. However, by 218 BC there were plebeian consuls and senators. The plebeians were in the senate and were able to obtain the consulship. The ultimate beneficiaries of the lex Claudia were probably the equestrian class, rich citizens not in the senate.[13] As rich traders, equestrians would not have been affected by the law and so would have been able to continue trading. If so, then the proposal for and then the passage of the lex Claudia would indicate a struggle not so much concerning patricians and plebeians, but senators and non-senators.

Reasons for the law

[edit]Warfare contributed to a significant portion of Rome's income.[14] As a result, war generals and their goods, including their ships, were needed. These war entrepreneurs usually came from higher-status men of the nobility, especially ranking officers.[15] Rome needed to fund these wars and so often required financial help from affluent people and their private fortune. In fact, some of these wealthy citizens had profitable currency manipulation schemes that helped supply the war effort with revenue.[16] An example of how personal wealth played a role in Roman governance was in the year 217 BC, a year after the lex Claudia was passed. The senate, which controlled the finances of Rome, refused to pay the ransom of a captured Roman citizen Fabius Maximus. Disappointed, but not deterred by this, Fabius Maximus paid his ransom from his own wealth.[17] This example, from a similar time as the lex Claudia, demonstrates that private wealth could be used in public affairs. It tells us that the public and private were intertwined. If a man was wealthy enough to pay his own ransom, then there were probably enough elite males with ample wealth and goods to contribute to war expenditure.

Money was also needed to pay soldiers.[18] The financial support of elites played a crucial role in supporting Roman desires to wage wars. They provided more than money though as they also served as privateers and ship owners in the First and Second Punic Wars.[19] They were the backbone with their financial investments which helped pave the way for Rome to introduce its precious metal currency to the empire.[20] The lex Claudia would be the solution to the corruption of Roman governance and prevent private investors from forcing further taxes from ordinary Roman citizens to increase private profit.[21] It was also a way of preventing senators from having any involvement in the transport of grain that was obtained through taxes.[22]

It is possible that the Second Punic War as well as profiteering influenced the passage of the lex Claudia. Many affluent Romans were involved in business as well as war, and an example of this is conflict over Saguntum.[23][24] This conflict foreshadowed the Second Punic War and the lex Claudia in a number of ways. Firstly, elite citizens profited from supplying provisions overseas for the war effort.[25] Secondly, it tells us about the links between Roman warfare and shipping. For when the Romans fought the Carthaginians in Spain and Africa for their lands, the commands were given to the consuls of 218 BC. One of the consuls, Sempronius Longus, was provided with 160 ships and the other consul, Cornelius Scipio, was provided with a fleet of 60 ships.[26] Both consuls had previously gained wealth during the First Punic War.[27] Furthermore during the Saguntum conflict, the two consuls may have also invested their money into their fleets to save for the potential wars to come and therefore were profiteering from their shipping, the kind of behaviour the lex Claudia would prohibit.[28] This could have been a reason why the lex Claudia came about – particularly as it was in the same year (218 BC). Many investors also appeared to play a major role in influencing the Second Macedonian War as well.[29] Indeed as these war entrepreneurs were potentially dissatisfied with the spoils of the First Punic War and the subsequent peace treaty, they pressed for another.

Provisions and passage

[edit]Provisions of the law

[edit]

A significant aspect of the lex Claudia was its specificity about the size and quantity of goods. The law stipulated that senators could not own ships that were large enough to carry 300 amphorae (or more). 300 amphorae was the size limitation that would still allow goods to be transferred from farming estates to the markets.[30] Assuming that full-sized amphora weighted approximately 38 kilograms, the maximum dead weight was just under 11.5 tonnes. This limit was a concrete way of preventing quaestus (which broadly refers to profit that does not derive from agriculture). To operate a vessel in quaestum was considered dishonourable for a senator.[31] Indeed Livy states that this size limitation reinforced the patrician distaste for making a profit through trade activity.[32] This implies that long-distance trade was primarily dictated by the senatorial class's domination of the sea. Furthermore, Livy describes the lex Claudia as a means to weaken the economic interest of the elite.[33] The lex Claudia aimed to minimise the distraction from the life of leisure that was necessary for the political affairs of senators, as well as prevent corruption and conflicts of interests.[34]

It is noteworthy that the law restricted senators' sons from owning large ships as well. This aspect undermines the principle of the hereditary advantage of elites, particularly patricians, which was a fundamental element of Roman society. Senators, the top of society in a culture obsessed with status, were restricted by this law in their ownership of ships. Therefore, those who benefited from the lex Claudia were the equestrian order, who were rich enough to invest in the ships and were not senators.

Passage of the law

[edit]The law's alternative title as plebiscitum Claudianum and the fact that Quintus Claudius was a tribune of the plebs both how the law was passed. The title plebiscitum refers to resolutions which were passed by the consilium plebis, the plebeian assembly, which was convened a presided over by the tribune of the plebs. Despite previous restrictions during this period, the passage of plebiscitum did not rely on the approval of the senate and were binding for all citizens. Although they accounted for a significant amount of Roman legislation, they remained a pathway for challenging the authority of the senate and this is most likely why lex Claudia was passed using this method, given the senatorial resistance to it.[35]

Supporters

[edit]The prominent figures involved with the passage of this law were tribune Quintus Claudius and Gaius Flaminius, the senator.[36] Unfortunately the only information known about Quintus Claudius is that he passed this law. On the other hand, Gaius Flaminius Nepos, while also a plebeian, had quite a distinguished career as a novus homo, even reaching the office of Censor. But his support of the unpopular lex Claudia was not the first time he came into conflict with the Senate. As a Tribune of the Plebs (232 BC), he apparently fought the Senate a lot in his attempt to pass a law providing needy settlers land in the ager Gallicus.[37] Furthermore when he was Consul, Flaminius was refused a triumph by the Senate after his victory against the Gallic Insubres (223 BC) due to his disregard for unfavourable omens, only for this judgement to be overturned by popular demand.[38][39] Due to his apparent affinity with the people, he has often been characterised as a demagogue, with Cicero even treating him as a precursor to the Gracchi.[40] On the other hand he still may have had support amongst the plebeian elite within the Senate, reducing his demagogic portrayal.[41] Nevertheless, Flaminius' resistance to the Senate arguably reflects the resurgence of the Struggle of the Orders between the patricians and plebeians during the Roman Republic. His plebeian sentiments against the Senate would explain his motivations behind supporting the lex Claudia and the manner in which it was passed, however this cannot be confirmed.

Enforcement

[edit]The fact that lex Claudia was obsolete by the late Roman Republic[42] seems to suggest a lack of enforcement. During the Republican period, Roman law was not codified and therefore compliance to laws relied upon how well they were known. As a result, the process of enforcement through prosecutions and self-regulation was integral to the future enforcement of the law. Therefore the disappearance of lex Claudia and limited mentions in ancient source material could indicate that the law was not well enforced. This is most likely because the patrician senators who opposed the law were responsible for its enforcement.

Reactions

[edit]The initial reactions to the law cannot be known conclusively due to the lack of contemporary evidence. From Livy's evidence, there were two main responses. Senators, as would be expected, were incensed by the law and Flaminius fled Rome shortly after it was passed.[43] However, it is interesting that elites would be in opposition to the law at all because traditionally, patricians saw profit-making through trade as anathema.[44] Since this law, by implication, restricted the amount of goods that could be transported at any one time, it was actually in-line with mos maiorum, the traditional way of doing things. Upper classes were subject to this strict set of traditions regarding behaviour that could be seen as improper for a member of their class.[45] If Livy's sources are correct, it would have been rather unusual that there was elite hostility towards the law. It is possible that a large number of senators at this time were plebeian and if so, they perhaps would not share this old value. Or it might be an example of laws taking precedence over mos maiorum. Indeed the abuse of mos maiorum's flexibility led to the increased use of regulations through statutory law rather than informal traditions.[46] In this view, the lex Claudia was a law that simply reinterpreted the tradition of patrician distaste for trade, applying it to all senators. In terms of senatorial dislike of the law, Flaminius himself was also unpopular, due to illegalities earlier in his career.[47] He may have already become a 'dead letter' by the time of Cato the Elder, however the moral stigma of the law may have still been present in society.[48]

On the other hand, the Roman populace appears to have welcomed the law. Livy tells us that through his support of the lex Claudia, Flaminius earned popularity and secured another consulship.

Although Cicero indicates that lex Claudia had become obsolete by the later Roman Republic,[49] the fact that he is prosecuting Verres for his actions in Sicily reveals that the actions of the senators during public commands remained a real concern and the subject of legislation throughout the Republican period. It seems likely the law became obsolete due to a combination of the senatorial class's dislike for it and the fact that as the empire grew, opportunities for corruption increased, meaning that trade was less of a concern.

Modern historiography

[edit]Whilst most modern historians share an overarching view regarding the intention of the lex Claudia, it has been interpreted differently by many scholars.

Intention of Lex Claudia

[edit]Most modern scholars agree that the lex Claudia was created with the intention to restrict the economic, social and political power of the elite class who posed a threat prior to the introduction of the law. Both Aubert and Feig Vishnia harmoniously interpret Livy's description[50] of the lex Claudia as a measure that was devised by politicians to weaken the economic interest of the elite.[51] D'Arms also agrees that the law was the result of an attempt to cut down on elite wealth and domination.[52] Additionally, Bleckmann observes that the Lex Claudia was established to help safeguard against war profiteers benefitting too greatly from the transportation of supplies by private citizens during a time of war.[53] Historians Claude Nicolet and Feig Vishnia have also proposed further intentions of the law. Nicolet also suggests that the lex Claudia forbid senators from pursuing 'any kind of activity for grain'.[54] Furthermore, Feig Vishnia suggests that the lex Claudia could have been intended not only to forbid the senators and their sons from owning sea-going ships whose capacity exceeded 300 amphorae, but also to obstruct a growing senatorial inclination to compete for military contracts.[55] However, she also acknowledges that this law may have been the reaction to the 'looming threat' of Hannibal advancing towards Italy in August September 218 BC.[56] She goes on to state that 'In the atmosphere of uncertainty, when people's anxiety and anger at their leader's miscalculation after the Second Illyrian War had yielded very little booty and senators who had opposed the Claudian measure withdrew their objection'.[57] Tchernia refers to a more superstitious intention suspected by Boudewijn Sirks who believed the Lex Claudia derived from an old religious taboo: that senators must avoid the sea because it signifies death. This alludes to old Roman fears and stories of the sea which was viewed as a tempting yet treacherous place of risk, evil, worry and "punic treachery".[58]

Effect of Lex Claudia and its implications

[edit]Whilst modern historians tend to share a similar, overarching view of the intention of the lex Claudia, the ways in which it actually had an effect appears to be a subject of debate. Within his work, D'Arms mentions that the law is a reaffirmation of traditional values, particularly landed aristocratic ideal, a desire to have senators revert to their mos maiorum.[59][60] This reflected a desire for the elite to focus on acquiring land rather than maritime exploits.[61] Aubert suggests that law highlights the growing power of the ruling class and, in turn, the fear of the Roman State who became threatened by the growing economic, social and political power of those who chose not to pursue a political career.[62] As a result, Aubert observes that the Roman State tightened the reins on economic activities of its ruling class to ensure its survival by preventing possible social and political devaluation that had resulted from 'entrepreneurship gone awry'.[63] According to Aubert the formation of the lex Claudia proved beneficial to the further development of the law of commerce.[64] Whilst Aubert appears certain of the effect that the law had, D'Arms points out that there was a clear evasion of the law in the Late Republic but that we can not be sure of the social mechanisms for evading the law.[65] Additionally, Bleckmann states that the law did in fact, lead to 'corrupt practices taking place among people of higher standing to make money'.[66] This observation is shared with Feig Vishnia who believed that an incident in 215-213 was the result of the implementation of the lex Claudia.

Beneficiaries

[edit]Whilst Livy's account[67] suggests that the economic interest of the elite would be weakened by the lex Claudia, modern scholars tend to agree that this is not at all the case. Within his work, Aubert states that those rich enough to afford large ships (mainly the equestrian order) were in fact the main beneficiaries of the law.[68] Contrastingly, within her account, Feig Vishnia believes that an incident that occurred in 215 BC reveals the beneficiaries of the law. She states that in 215 BC, the senate had to turn to 'those who had increased their property from public contracts'[69] to financially support Spanish armies with the promise that they would be reimbursed.[70] In 213 BC, publicans abused this term by reporting fictitious shipwrecks and demanding compensation from the State.[71] According Feig Vishnia, this incident symbolises that the publicans who owned sea going ships were the chief beneficiaries of the Lex Claudia.[72]

Aftermath

[edit]Cicero alludes that since 218 BC the prohibition had become an unexceptional part of everyday life for the senators – and apparently this would continue until the fourth century AD.[73] Although D'arms suggests that the lex Claudia may have already become outdated by Cicero's time in 70 BC.[74] This observation appears to be shared by Nicolet who suggests that 'this had already become a dead letter by the time of the elder Cato who lent money on bottomry (a system of merchant insurance in which a ship is used as security against a loan to finance a voyage, the lender losing their money if the ship sinks), but the moral stigma remained'.[75]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Aubert, Jean-Jacques. "The Republican Economy and Roman Law: Regulation, Promotion or Reflection?" from Flower, Harriet (ed.) Cambridge Companion to Roman History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004)

- ^ Bringmann, Klaus. "The Roman Republic and its Internal Politics between 232 and 167 BCE" from Mineo, Bernard (ed.) A Companion to Livy. (Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2015).

- ^ D'Arms, John, H. Commerce and Social Standing in Ancient Rome. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981), p. 5.

- ^ Livy, History of Rome, 21.63.3 http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Liv.+21.63&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0144

- ^ Cicero, Against Verres, 2.5.45, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Cic.+Ver.+2.5.45&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0018

- ^ D'Arms p. 34–37

- ^ D'Arms p. 34

- ^ D'Arms p. 34–35

- ^ Aubert p. 167

- ^ Aubert p. 174

- ^ D'Arms p. 31

- ^ Bringmann p. 396

- ^ Aubert

- ^ Bleckmann, Bruno. "Roman War Finances in the Age of the Punic Wars" from Hans Beck, Martin Jehne and John Serrati (eds.) Money and Power in the Roman Republic. (Brussels: Editions Latomus, 2016), p. 84

- ^ Bleckmann p. 88

- ^ Bleckmann p. 86

- ^ Bleckmann p. 91

- ^ Bleckmann p. 96

- ^ Bleckmann p. 96

- ^ Bleckmann p. 96

- ^ Bleckmann p. 96

- ^ Tchernia, Andre. The Romans and Trade. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

- ^ Rosenstein, Nathan. Rome and the Mediterranean 290-146BC: The Imperial Republic. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012) p. 21

- ^ Scullard, H.H. "The Carthaginians in Spain" from A. E. Astin , F. W. Walbank , M. W. Frederiksen , R. M. Ogilvie (eds) The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 8: Rome and the Mediterranean to 133 BC (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), p. 25–26

- ^ Bleckmann p. 93

- ^ Bleckmann p. 93

- ^ Bleckmann p. 93

- ^ Bleckmann p. 93

- ^ Bleckmann p. 95

- ^ Aubert p. 174

- ^ Tchernia

- ^ Livy 21.63.3

- ^ Livy 21.63

- ^ Aubert

- ^ Stavley, Eastland Stuart and Spawforth, Antony J.S. "Plebiscitum" from Simon Hornblower, Antony Spawforth and Esther Eidinow (eds.) The Oxford Classical Dictionary. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

- ^ Livy 21.63.3

- ^ Polybius 2.21

- ^ Livy 21.63.2

- ^ Plut. Marcellus 4

- ^ Cic. Acad. 2.13

- ^ Elvers, Karl-Ludwig (Bochum), "Flaminius" from Hubert Cancik and Helmuth Schneider (eds.) Brill's New Pauly, 2006.

- ^ Cic. Verr. 2.5.45

- ^ Livy 21.63.3-5

- ^ Livy 21.63.3

- ^ Nicolet, Claude (trans. P.S. Falla). The World of the Citizen in Republican Rome. (London: Batsford Academic and Educational, 1980), p. 80

- ^ Hölkeskamp, Karl. Reconstructing the Roman Republic: An Ancient Political Culture and Modern Research. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010).

- ^ Livy 21.63.2

- ^ Nicolet p. 80

- ^ Cic. Verr. 2.5.45

- ^ Livy 21.63

- ^ Aubert p. 174

- ^ D'Arms p. 31

- ^ Bleckmann p. 96

- ^ Nicolet p. 80

- ^ Feig Visnia, Rachel. State, Society and Popular Leaders in Mid-Republican Rome 241-167 B.C. (New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 39

- ^ Feig Visnia p. 42

- ^ Feig Visnia p. 43

- ^ Tchernia p. 170

- ^ D'Arms p. 33

- ^ Tchernia

- ^ D'Arms p. 33

- ^ Aubert p. 174

- ^ Aubert p. 175

- ^ Aubert p. 175

- ^ D'Arms p. 39

- ^ Bleckmann p. 96

- ^ Livy 21.63

- ^ Aubert p. 174

- ^ Livy 23.48.10

- ^ Feig Visnia p. 41

- ^ Feig Visnia p. 40

- ^ Feig Vishnia p. 40

- ^ Tchernia

- ^ D'Arms p. 37

- ^ Nicolet p. 80